Spironolactone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | spy-ROW-no-LAK-tone[1] or speer-OH-no-LAK-tone[2] |

| Trade names | Aldactone, Spiractin, Verospiron, many others; combinations: Aldactazide (+HCTZ), Aldactide (+HFMZ), Aldactazine (+altizide), others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682627 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth,[3] topical[4] |

| ATC code | C03DA01 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80–90%[5][6] |

| Protein binding |

Spironolactone: 88% (to albumin and AGP equivalently)[7] Canrenone: 99.2% (to albumin)[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver (deacetylation, dethiolation, and thiomethylation)[5][6] |

| Metabolites |

7α-TMS, 6β-OH-7α-TMS, canrenone, others[5][6][8] (All three active)[9] |

| Biological half-life |

Spironolactone: 1.4 hours[5] 7α-TMS: 13.8 hours[5] 6β-OH-7α-TMS: 15.0 hours[5] Canrenone: 16.5 hours[5] |

| Excretion | Urine, bile[6] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | SC-9420; 7α-Acetylthio-17α-hydroxy-3-oxopregn-4-ene-21-carboxylic acid γ-lactone |

| CAS Number |

52-01-7 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5833 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 2875 |

| DrugBank |

DB00421 |

| ChemSpider |

5628 |

| UNII |

27O7W4T232 |

| KEGG |

D00443 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:9241 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1393 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

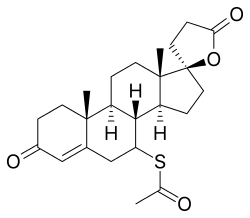

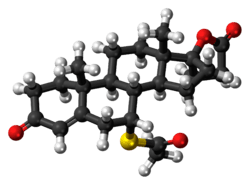

| Formula | C24H32O4S |

| Molar mass | 416.574 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Spironolactone, marketed under the brand name Aldactone among others, is a medication that is primarily used to treat fluid build-up due to heart failure, liver scarring, or kidney disease.[3] It is also used in the treatment of high blood pressure, low blood potassium that do not improve with supplementation, early-onset puberty, and acne and excessive hair growth in women.[3][10] It is also a part of hormone therapy in transgender women.[11] Spironolactone is taken by mouth.[3]

Common side effects include electrolyte abnormalities particularly high blood potassium, nausea, vomiting, headache, rashes, and a decreased desire for sex. In those with liver or kidney problems, extra care should be taken.[3] Spironolactone has not been well studied in pregnancy and should not be used to treat high blood pressure of pregnancy.[12] It is a steroid that blocks the effects of aldosterone and testosterone and has progesterone-like effects. Spironolactone belongs to a class of medications known as potassium-sparing diuretics.[3]

Spironolactone was introduced in 1959.[13][14] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[15] It is available as a generic medication.[3] The wholesale cost in the developing world as of 2014 is between 0.02 and 0.12 USD per day.[16] In the United States it costs about 0.50 USD per day.[3]

Medical uses

Spironolactone is used primarily to treat heart failure, edematous conditions such as nephrotic syndrome or ascites in people with liver disease, essential hypertension, hypokalemia, secondary hyperaldosteronism (such as occurs with hepatic cirrhosis), and Conn's syndrome (primary hyperaldosteronism). On its own, spironolactone is only a weak diuretic because it primarily targets the distal nephron (collecting tubule), where only small amounts of sodium are reabsorbed, but it can be combined with other diuretics to increase efficacy.

Spironolactone is an antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR) as well as an inhibitor of androgen production. Due to the antiandrogenic effects that result from these actions, it is frequently used off-label to treat a variety of dermatological conditions in which androgens, such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), play a role. Some of these uses include androgenic alopecia in men (either at low doses or as a topical formulation) and women, and hirsutism (excessive hair growth), acne, and seborrhea in women.[17] Spironolactone is the most commonly used drug in the treatment of hirsutism in the United States.[18] Higher doses of spironolactone are not recommended in males due to the high risk of feminization and other side effects. Similarly, it is also commonly used to treat symptoms of hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome.[19]

There is tentative low quality evidence supporting its use in female pattern hair loss.[20]

High blood pressure

About one person in one hundred with hypertension has elevated levels of aldosterone; in these people, the antihypertensive effect of spironolactone may exceed that of complex combined regimens of other antihypertensives since it targets the primary cause of the elevated blood pressure. However, a Cochrane review found adverse effects at high doses and little effect on blood pressure at low doses in the majority of people with high blood pressure.[21] There is no evidence of person oriented outcome at any dose in this group.[21]

Heart failure

While loop diuretics remain first-line for most people with heart failure, spironolactone has shown to reduce both morbidity and mortality in numerous studies and remains an important agent for treating fluid retention, edema, and symptoms of heart failure. Current recommendations from the American Heart Association are to use spironolactone in patients with NYHA Class II-IV heart failure who have a left ventricular ejection fraction of <35%.[22]

In a randomized evaluation which studied people with severe congestive heart failure, people treated with spironolactone were found to have a relative risk of death of 0.70 or an overall 30% relative risk reduction compared to the placebo group, indicating a significant death and morbidity benefit of the drug. Patients in the study's intervention arm also had fewer symptoms of heart failure and were hospitalized less frequently.[23] Likewise, it has shown benefit for and is recommended in patients who recently suffered a heart attack and have an ejection fraction less than 40%, who develop symptoms consistent with heart failure, or have a history of diabetes mellitus. Spironolactone should be considered a good add-on agent, particularly in those patients "not" yet optimized on ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers.[22] Of note, a recent randomized, double-blinded study of spironolactone in patients with symptomatic heart failure with "preserved" ejection fraction (i.e. >45%) found no reduction in death from cardiovascular events, aborted cardiac arrest, or hospitalizations when spironolactone was compared to placebo.[24]

It is recommended that alternatives to spironolactone be considered if serum creatinine is >2.5 mg/dL (221µmol/L) in males or >2 mg/dL (176.8 µmol/L) in females, if glomerular filtration rate is below 30mL/min or with a serum potassium of >5.0 mEq/L given the potential for adverse events detailed elsewhere in this article. Doses should be adjusted according to the degree of renal function as well.[22]

According to systematic review, in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, treatment with spironolactone did not improve patient outcomes. This is based on the TOPCAT Trial examining this issue, which found that of those treated with placebo had a 20.4% incidence of negative outcome vs 18.6% incidence of negative outcome with spironolactone. However, because the p-value of the study was 0.14, and the unadjusted hazard ratio was 0.89 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.77 to 1.04, it is determined the finding had no statistical significance. Hence the finding that patient outcomes are not improved with use of spironolactone.[25]

Due to its antiandrogen properties, spironolactone can cause effects associated with low androgen levels and hypogonadism in males. For this reason, men are typically not prescribed spironolactone for any longer than a short period of time, e.g., for an acute exacerbation of heart failure. A newer drug, eplerenone, has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of heart failure, and lacks the antiandrogen effects of spironolactone. As such, it is far more suitable for men for whom long-term medication is being chosen. However, eplerenone may not be as effective as spironolactone or the related drug canrenone in reducing mortality from heart failure.[26]

The clinical benefits of spironolactone as a diuretic are typically not seen until 2–3 days after dosing begins. Likewise, the maximal antihypertensive effect may not be seen for 2–3 weeks.

Unlike with some other diuretics, potassium supplementation should not be administered while taking spironolactone, as this may cause dangerous elevations in serum potassium levels resulting in hyperkalemia and potentially deadly cardiac arrythmias.

Acne in women

Because of spironolactone's antiandrogen effects, it can be quite effective in clearing severe acne conditions, such as cystic acne, caused by slightly elevated or elevated levels of testosterone in women. In reducing the levels of testosterone, excess oil that is naturally produced in the skin is also reduced. Though not the primary intended purpose of the medication, its ability to be helpful with problematic skin and acne conditions was discovered to be one of the beneficial side effects and has been quite successful. Oftentimes, for women treating acne, spironolactone is prescribed and paired with a birth control pill. A significant number of patients have reported that they have seen positive results in the pairing of these two medications, although these results may not be seen for up to three months.

Transgender hormone therapy

Spironolactone is frequently used as a component of hormone replacement therapy in transgender women, especially in the United States (where cyproterone acetate is not available), usually in addition to an estrogen.[27][28][29] Spironolactone significantly depresses plasma testosterone levels, reducing them to female/castrate levels at sufficient doses and in combination with estrogen. The clinical response consists of, among other effects, decreased male pattern body hair, the induction of breast development, feminization in general, and lack of spontaneous erections.[29]

Comparison with other antiandrogens

There are few available options for antiandrogen therapy. Spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, and flutamide are some of the most well-known and widely used drugs.[30] Compared to cyproterone acetate, spironolactone is considerably less potent as an antiandrogen by weight and binding affinity to the androgen receptor.[31][32] However, despite this, at the doses of which they are typically used, spironolactone and cyproterone acetate have been found to be generally about equivalent in terms of effectiveness for a variety of androgen-related conditions,[33] though, cyproterone acetate has shown a slight though non-statistically-significant advantage in some studies.[34][35] Also, it has been suggested that cyproterone acetate could be more effective in cases where androgen levels are more pronounced, though this has not been proven.[33]

Flutamide, another frequently used antiandrogen which is non-steroidal and a pure androgen receptor antagonist, though much less potent by weight and binding affinity than either spironolactone or cyproterone acetate,[36][37] has been found to be more effective than either of them as an antiandrogen when it is used at the typical treatment doses.[31][38][39] Unfortunately, the uses of both cyproterone acetate and flutamide have been associated with hepatotoxicity, which can be severe with flutamide and has resulted in the withdrawal of cyproterone acetate from the United States drug market for this indication. Bicalutamide is a more potent, safer, and more tolerable alternative to flutamide, but is relatively little-studied in the treatment of androgen-dependent conditions aside from prostate cancer, though it has been used to treat hirsutism with success. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues are another very effective option for antiandrogen therapy, but have not been widely employed for this purpose due to their high cost and limited insurance coverage despite many now being available as generics.[28] As such, spironolactone may be the only practical, safe, available, and well-supported antiandrogen option in some cases.

In a study of the predictive markers for transgender women requesting breast augmentation, there was a significantly higher rate of those treated with spironolactone requesting breast augmentation compared to other antiandrogens such as cyproterone acetate or GnRH analogues, which was interpreted by the study authors as being potentially indicative that spironolactone may result in poorer breast development in comparison.[40] This may be related to the fact that spironolactone has been regarded as a comparatively weak antiandrogen relative to other options.[41]

Available forms

Spironolactone is usually used in the form of oral tablets.[42][43][44] The drug has also been marketed in the form of 2% and 5% topical cream in Italy for the treatment of acne and hirsutism under the brand name Spiroderm, although this product is no longer available.[45][4]

Contraindications

Contraindications of spironolactone include hyperkalemia (high levels of potassium) among others.

Side effects

The most common side effect of spironolactone is urinary frequency. Other general side effects include dehydration, hyponatremia (low sodium levels), mild hypotension (low blood pressure),[46] ataxia (muscle incoordination), drowsiness, dizziness,[46] dry skin, and rashes. Because it reduces androgen levels and blocks androgen receptors, spironolactone can, in men, cause breast tenderness, gynecomastia (breast development), and feminization in general, as well as testicular atrophy, reversibly reduced fertility, and sexual dysfunction including loss of libido and erectile dysfunction.[47] In women, spironolactone can cause menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, and breast enlargement.[17][48]

The most important potential side effect of spironolactone is hyperkalemia (high potassium levels), which, in severe cases, can be life-threatening. Hyperkalemia in these patients can present as a non anion-gap metabolic acidosis. Spironolactone may put patients at a heightened risk for gastrointestinal issues like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramping, and gastritis. In addition, there has been some evidence suggesting an association between use of the drug and bleeding from the stomach and duodenum, though a causal relationship between the two has not been established.[49] Also, spironolactone has been shown to be immunosuppressive in the treatment of sarcoidosis.[50]

Hyperkalemia

Spironolactone can cause hyperkalemia, which can, rarely, be fatal.[51] Of those prescribed typical doses, 10% to 15% developed hyperkalemia,[51] and in 6%, it was severe.[51] An increase in the rates of hospitalization (from 0.2% to 11%) and death (from 0.3 per 1,000 to 2.0 per 1,000) due to hyperkalemia from 1994 to 2001 has been attributed to a parallel rise in the number of prescriptions written for spironolactone following the publication of the RALES study.[51] The risk of hyperkalemia with spironolactone treatment is greatest in the elderly, in people with renal impairment, and in people simultaneously taking potassium supplements or ACE inhibitors.[51]

Breast events

In women, spironolactone is commonly associated with breast pain and breast enlargement,[52][53] "probably because of [indirect] estrogenic effects on target tissue."[51] Breast enlargement may occur in 26% of women and is described as mild,[46] while breast tenderness is reported to occur in up to 40% of women taking high dosages of the drug.[54] Spironolactone also commonly and dose-dependently produces gynecomastia (woman-like breasts) as a side effect in men.[55][56][57][52] At low dosages, the rate is only 5–10%,[57] but at high dosages, up to or exceeding 50% of men may develop gynecomastia.[56][55][52] The severity of the gynecomastia varies considerably, but is usually mild.[55] As with women, gynecomastia associated with spironolactone is commonly although inconsistently accompanied by breast tenderness.[55] Gynecomastia induced by spironolactone usually regresses after a few weeks following discontinuation of the drug.[55]

Menstrual disturbances

In women, menstrual disturbances are common during spironolactone treatment, with 10 to 50% of women experiencing them at moderate doses and almost all experiencing them at a high doses.[46][51] Most women taking moderate doses of spironolactone develop amenorrhea, and normal menstruation usually returns within two months of discontinuation.[51] Spironolactone produces an irregular, anovulatory pattern of menstrual cycles[46] It is also associated with metrorrhagia and menorrhagia (or menometrorrhagia) in a large percentage of women.[53] It is thought that its weak progestogenic activity is responsible for this effect, although this has not been adequately evaluated nor firmly established.[46] An alternative proposed cause is inhibition of 17α-hydroxylase and hence sex steroid metabolism by spironolactone and consequent changes in sex hormone levels.[55]

The menstrual disturbances associated with spironolactone can usually be controlled well by concomitant treatment with an oral contraceptive.[46]

Infertility

At high dosages, spironolactone has been associated with semen abnormalities such as decreased sperm count and motility in men.[55]

Depression

Increased glucocorticoid activity in the body is associated with depression.[58][59] As such, it is thought that there may be a risk of depression with spironolactone treatment.[58][60][61] Some clinical research supports this notion.[40][62][63]

Rare reactions

Spironolactone may rarely cause more severe side effects such as anaphylaxis, renal failure, hepatitis (two reported cases, neither serious),[64] agranulocytosis, DRESS syndrome, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis.[65][66] Five cases of breast cancer in patients who took spironolactone for prolonged periods of time have been reported.[51][57] It should also be used with caution in people with some neurological disorders, anuria, acute kidney injury, or significant impairment of renal excretory function with risk of hyperkalemia.[67]

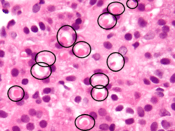

Spironolactone bodies

Long-term administration of spironolactone gives the histologic characteristic of spironolactone bodies in the adrenal cortex. Spironolactone bodies are eosinophilic, round, concentrically laminated cytoplasmic inclusions surrounded by clear halos in preparations stained with hematoxylin and eosin.[68]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Spironolactone is considered Pregnancy Category C meaning that it is unclear if it is safe for use during pregnancy.[3] Likewise, it has been found to be present in the breast milk of lactating mothers and, while the effects of spironolactone or its metabolites have not been extensively studied in breast-feeding infants, it is generally recommended that women also not take the drug while nursing.[67]

Spironolactone is able to cross the placenta.[53] A study found that spironolactone was not associated with teratogenicity in the offspring of rats.[69][70][71] Because it is an antiandrogen however, spironolactone could theoretically have the potential to cause feminization of male fetuses at sufficient doses.[69][70] In accordance, a subsequent study found that partial feminization of the genitalia occurred in the male offspring of rats that received doses of spironolactone that were five times higher than those normally used in humans (200 mg/kg per day).[69][71] Another study found permanent, dose-related reproductive tract abnormalities rat offspring of both sexes at lower doses (50 to 100 mg/kg per day).[71] In practice however, although experienced is limited, spironolactone has never been reported to cause observable feminization or any other congenital defects in humans.[69][70][72][73] Among 31 human newborns exposed to spironolactone in the first trimester, there were no signs of any specific birth defects.[73] A case report described a woman who was prescribed spironolactone during pregnancy with triplets and delivered all three (one boy and two girls) healthy; there was no feminization in the boy.[73] In addition, spironolactone has been used at high doses to treat pregnant women with Bartter's syndrome, and none of the infants (three boys, two girls) showed toxicity, including feminization in the male infants.[69][74] There are similar findings, albeit also limited, for another antiandrogen, cyproterone acetate (prominent genital defects in male rats, but no human abnormalities (including feminization of male fetuses) at both a low dose of 2 mg/day or high doses of 50 to 100 mg/day).[73] In any case, spironolactone is nonetheless not recommended during pregnancy due to theoretical concerns relating to feminization of males and also to potential alteration of fetal potassium levels.[69][75]

Only very small amounts of spironolactone and its metabolite canrenone enter breast milk, and the amount received by an infant during breastfeeding (<0.5% of the mother's dose) is considered to be insignificant.[74]

Interactions

Spironolactone often increases serum potassium levels and can cause hyperkalemia, a very serious condition. Therefore, it is recommended that people using this drug avoid potassium supplements and salt substitutes containing potassium.[76] Physicians must be careful to monitor potassium levels in both males and females who are taking spironolactone as a diuretic, especially during the first twelve months of use and whenever the dosage is increased. Doctors may also recommend that some patients may be advised to limit dietary consumption of potassium-rich foods. However, recent data suggests that both potassium monitoring and dietary restriction of potassium intake is unnecessary in healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne.[77]

Research has suggested that spironolactone may be able to interfere with the effectiveness of antidepressant treatment. As the drug acts as an antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor, it is thought that it may reduce the effectiveness of certain antidepressants by interfering with normalization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and increasing glucocorticoid levels.[78][79] However, other research contradicts this hypothesis and has suggested that spironolactone may actually produce antidepressant-like effects in animals.[80]

Spironolactone can also have numerous other interactions, most commonly with other cardiac and blood pressure medications.[67] Spironolactone together with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole increases the likelihood of hyperkalemia, especially in the elderly. The trimethoprim portion acts to prevent potassium excretion in the distal tubule of the nephron.[81]

Pharmacology

| [82] | Spironolactone | Eplerenone |

|---|---|---|

| MR (IC50) | 2 nM | 81 nM |

| AR (IC50) | 13 nM | 4827 nM |

| PR (EC50) | 2619 nM | >100 μM |

| GR (IC50) | 2899 nM | >100 μM |

| MR (IC50): 50% inhibition of activation by 0.5 nM aldosterone AR (IC50): 50% inhibition of activation by 10 nM dihydrotestosterone PR (EC50): 50% activation compared to 5 nM progesterone GR (IC50): 50% inhibition of activation by 5 nM dexamethasone | ||

Spironolactone is known to possess the following pharmacological activity:[83]

- Mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonist

- Androgen receptor (AR) antagonist/very weak partial agonist

- Progesterone receptor (PR) agonist

- Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) antagonist

- Pregnane X receptor (PXR) agonist (and thus CYP3A4[84] and P-glycoprotein inducer)[85][86][87]

- Steroid 11β-hydroxylase, aldosterone synthase, and 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase inhibitor

There is also evidence that spironolactone may block voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels.[88][89]

It should be noted however that these activities apply to the spironolactone molecule itself, but spironolactone is a prodrug, and for this reason, the actual in vivo clinical profile of spironolactone may differ from the activities and effective and inhibitory concentrations described above and to the right.

Antimineralocorticoid activity

Spironolactone inhibits the effects of mineralocorticoids, namely, aldosterone, by displacing them from mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) in the cortical collecting duct of renal nephrons. This decreases the reabsorption of sodium and water, while limiting the excretion of potassium (A K+ sparing diuretic). The drug has a slightly delayed onset of action, and so it takes several days for diuresis to occur. This is because the MR is a nuclear receptor which works through regulating gene transcription and gene expression, in this case to decrease the production and expression of ENaC and ROMK electrolyte channels in the distal nephrons. In addition to direct antagonism of the MRs, the antimineralocorticoid effects of spironolactone may also in part be mediated by direct inactivation of steroid 11β-hydroxylase and aldosterone synthase (18-hydroxylase), enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of mineralocorticoids. If levels of mineralocorticoids are decreased then there are lower circulating levels to compete with spironolactone to influence gene expression as mentioned above.[90]

Antiandrogenic activity

Spironolactone mediates its antiandrogenic effects via multiple actions, including the following:

- Direct blockade of androgens from interacting with the androgen receptor.[91][55] It should be noted however that spironolactone, similarly to other steroidal antiandrogens such as cyproterone acetate, is not a pure, or silent, antagonist of the androgen receptor, but rather a weak partial agonist with the capacity for both agonist and antagonist effects.[92][93][94] However, in the presence of significant enough levels of potent full agonists like testosterone and DHT,[94] the cases in which it is usually used even with regards to the "lower" relative levels present in females, spironolactone will behave similar to a pure antagonist. Nonetheless, there may still be a potential for spironolactone to produce androgenic effects (i.e. act as a receptor agonist) in the body at sufficiently high doses and/or in those with low enough endogenous androgen concentrations. As an example, one condition in which spironolactone is contraindicated is prostate cancer,[95] as the drug has been shown in vitro to significantly accelerate carcinoma growth in the absence of any other androgens, and was found to do so at the relatively high rate of approximately 32%, which was about 35% that of DHT (thus also indicating that its potential intrinsic activity at the androgen receptor may be somewhere around one-third that of endogenous full agonists).[92] In accordance, two case reports have described significant worsening of prostate cancer with spironolactone treatment in patients with the disease, leading the authors to conclude that spironolactone has the potential for androgenic effects in some contexts and that it should perhaps be considered to be a selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM).[96][97]

- Inhibition of 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-desmolase, enzymes in the androgen biosynthesis pathway, which in turn results in decreased testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels.[55][98][99][100] Though, its inhibition of these enzymes is said to be relatively weak.[37]

- There is mixed/conflicting evidence that spironolactone may inhibit 5α-reductase to some extent.[91][101][102][103][104]

- Acceleration of the rate of metabolism/clearance of testosterone by enhancing the rate of peripheral conversion of testosterone into estradiol.[99]

Other actions

Progestogenic activity

Spironolactone has weak progestogenic activity.[37][105] Its actions in this regard are a result of direct agonist activity at the progesterone receptor, but with a half-maximal potency approximately one-tenth that of its inhibition of the androgen receptor.[83] Spironolactone's progestogenic activity may be responsible for some of its side effects,[106] including the menstrual irregularities seen in women and the undesirable serum lipid profile changes that are seen at higher doses.[36][107][108] They may also serve to augment the gynecomastia caused by the estrogenic effects of spironolactone,[109] as progesterone is known to be involved in breast development.[110]

Estrogenic activity

Spironolactone does not bind to the estrogen receptor but has some indirect estrogenic effects which it mediates via several actions, including the following:

- By acting as an antiandrogen, as androgens suppress both estrogen production and action, for instance in breast tissue.[55][111]

- Displacement of estrogens from sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG).[98] This occurs because spironolactone binds to SHBG at a relatively high rate, as do endogenous estrogens and androgens, but estrogens like estradiol and estrone are more easily displaced than are androgens like testosterone. As a result, spironolactone blocks relatively more estrogens from interacting with SHBG than androgens, resulting in a higher ratio of free estrogens to free androgens.[112]

- Inhibition of the conversion of estradiol to estrone, resulting in an increase in the ratio of estradiol to estrone.[113] This is important because estradiol is approximately 10 times as potent as estrone as an estrogen.[114]

- Enhancement of the rate of peripheral conversion of testosterone to estradiol, thus further lowering testosterone levels and increasing estradiol levels.[99]

Inhibition of steroidogenesis

Spironolactone is said to possess very little or no antigonadotropic activity, even at high dosages.[53][115] (Though conflicting reports exist.)[48][116][117] In fact, the drug can actually increase gonadotropin levels by inhibiting androgen negative feedback on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis via blockade of the AR.[53] However, spironolactone is effective in lowering testosterone levels at high dosages in spite of not acting as an antigonadotropin, and this is thought to be due to direct enzymatic inhibition of 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase.[118][119][120]

Glucocorticoid activity

Spironolactone has been shown to inhibit steroid 11β-hydroxylase, an enzyme that is essential for the production of the glucocorticoid hormone cortisol. Because of this, glucocorticoid levels might be expected to be lowered, and hence, spironolactone might have some antiglucocorticoidic effects. In clinical practice however, this has not been found to be the case; spironolactone has actually been found to increase cortisol levels, both with acute and chronic administration. Research has shown that this is due to antagonism of the MR, which suppresses negative feedback on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis positively regulates the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn signals the adrenal glands, the major source of corticosteroid biosynthesis in the body, to increase production of both mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids. Therefore, by antagonizing the MR, spironolactone causes an increase in ACTH secretion and by extension an indirect rise in cortisol levels.[121][122] As such, any antiglucocorticoid activity of spironolactone via direct suppression of glucocorticoid synthesis (at the level of the adrenals) appears to be more than fully offset by its concurrent indirect stimulatory effects on glucocorticoid production.

At the same time, spironolactone weakly binds to and acts as an antagonist of the GR, showing antiglucocorticoid properties, but to a significant degree only at very high concentrations.[83][123][124]

Pharmacokinetics

Spironolactone has a relatively slow onset of action, with the peak antimineralocorticoid effect sometimes occurring 48 hours or more after the first dose.[5][6] Steady-state concentrations are achieved within 8 days.[125] The majority of spironolactone is eliminated by the kidneys, while minimal amounts are handled by biliary excretion.[126] The bioavailability of spironolactone improves significantly when it is taken with food.[127][128] Spironolactone induces the enzyme CYP3A4, which can result in interactions with various drugs.[129] It is not metabolized by CYP3A4, unlike the related drug eplerenone.[130] Spironolactone has poor water solubility, and for this reason, only oral formulations are available and other routes of administration such as intravenous have not been developed.[5]

Distribution

Spironolactone and its metabolite canrenone are highly plasma protein bound (88.0% and 99.2%, respectively).[5][7] Spironolactone is bound equivalently to albumin and α1-acid glycoprotein, while canrenone is bound only to albumin.[5][7] The plasma protein binding of the other metabolites of spironolactone, namely 7α-TMS and 6β-OH-7α-TMS, has not been assessed.

Metabolism

Spironolactone is rapidly and extensively metabolized in the liver upon oral administration and has a short terminal half-life of 1.4 hours.[5][6] The major metabolites of spironolactone are 7α-thiomethylspironolactone (7α-TMS), 6β-hydroxy-7α-thiomethylspironolactone (6β-OH-7α-TMS), and canrenone,[5][6][131] and have much longer half-lives in comparison (13.8 hours, 15.0 hours, and 16.5 hours, respectively).[5][6] These metabolites are responsible for the therapeutic effects of spironolactone.[5][6] As such, spironolactone is a prodrug.[132] Until recently, the 7α-thiomethylated metabolites of spironolactone had not been identified and it was thought that canrenone was the major active metabolite.[5][125][131] However, they have since been characterized, 7α-TMS has been identified as the predominant metabolite of spironolactone, and it has been determined that 7α-TMS accounts for around 80% of the potassium-sparing effect of the drug[5][125][131] while canrenone accounts for 10–25%.[133] In accordance, 7α-TMS occurs at higher circulating concentrations than does canrenone and has a higher relative affinity for the MR.[131] Other known metabolites of spironolactone include 7α-thiospironolactone, the 7α-methyl ethyl ester of spironolactone, and the 6β-hydroxy-7α-methyl ethyl ester of spironolactone.[8]

Active metabolites

Canrenone is an antagonist of the MR similarly to spironolactone,[2] but is slightly more potent in comparison.[6][134] In addition, canrenone inhibits steroidogenic enzymes such as 11β-hydroxylase, cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme, 17α-hydroxylase, and 21-hydroxylase similarly to spironolactone, but once again is more potent in doing so in comparison.[135]

In vitro, canrenone binds to and blocks the AR.[55] However, relative to spironolactone, canrenone is described as having very weak affinity to the AR.[41] In accordance, replacement of spironolactone with canrenone in male patients has been found to reverse spironolactone-induced gynecomastia, suggesting that canrenone is comparatively much less potent in vivo as an antiandrogen.[55] As such, based on the above, the antiandrogen effects of spironolactone are considered to be largely due to other metabolites rather than due to canrenone.[55][136][137]

Chemistry

Spironolactone is a steroidal 17α-spirolactone, or more simply a spirolactone, and is structurally related to other clinically used spirolactones such as canrenone, potassium canrenoate, drospirenone, and eplerenone, as well as the never marketed spirolactones SC-5233, prorenone, mexrenone, mespirenone, and spirorenone.

Chemical names

Spironolactone is also known by the following equivalent chemical names:

- 7α-Acetylthio-17α-hydroxy-3-oxopregn-4-ene-21-carboxylic acid γ-lactone

- 7α-Acetylthio-3-oxo-17α-pregn-4-ene-21,17β-carbolactone

- 3-(3-Oxo-7α-acetylthio-17β-hydroxyandrost-4-en-17α-yl)propionic acid lactone

- 7α-Acetylthio-17α-(2-carboxyethyl)androst-4-en-17β-ol-3-one γ-lactone

- 7α-Acetylthio-17α-(2-carboxyethyl)testosterone γ-lactone

Society and culture

Generic name

The English, French, and generic name of spironolactone is spironolactone (pronounced as spy-ROW-no-LAK-tone[1] or as speer-OH-no-LAK-tone[2] according to difference sources) and this is its INN, USAN, BAN, DCF, and JAN.[138][45][139] Its name is spironolactonum in Latin, spironolacton in German, espironolactona in Spanish and Portuguese, and spironolattone in Italian (which is also its DCIT).[138][45][139]

Spironolactone is also known by its developmental code name SC-9420.[138][45]

Brand names

Spironolactone is marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.[138][45] The major brand name of spironolactone is Aldactone.[138][45] Other important brand names include Aldactone-A, Berlactone, Espironolactona, Espironolactona Genfar, Novo-Spiroton, Prilactone (veterinary), Spiractin, Spiridon, Spirix, Spiroctan, Spiroderm (discontinued),[4] Spirogamma, Spirohexal, Spirolon, Spirolone, Spiron, Spironolactone Actavis, Spironolactone Orion, Spironolactone Teva, Spirotone, Tempora (veterinary), Uractone, Uractonum, Verospiron, and Vivitar.[138][45]

Spironolactone is also formulated in combination with a variety of other drugs, including with hydrochlorothiazide as Aldactazide, with hydroflumethiazide as Aldactide, Lasilacton, Lasilactone, and Spiromide, with altizide as Aldactacine and Aldactazine, with furosemide as Fruselac, with benazepril as Cardalis (veterinary), with metolazone as Metolactone, with bendroflumethiazide as Sali-Aldopur, and with torasemide as Dytor Plus, Torlactone, and Zator Plus.[138]

Availability

Spironolactone is marketed widely throughout the world and is available in almost every country, including in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, other European countries, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Central and South America, and East and Southeast Asia.[138][45]

Research

Epstein–Barr virus

Spironolactone has been found to block Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) production and that of other human herpesviruses by inhibiting the function of an EBV protein SM, which is essential for infectious virus production.[140] This effect of spironolactone was determined to be independent of its antimineralocorticoid actions.[140] Thus, spironolactone or compounds based on it have the potential to yield novel antiviral drugs with a distinct mechanism of action and limited toxicity.[140]

References

- 1 2 Kevin R. Loughlin; Joyce A. Generali (2006). The Guide to Off-label Prescription Drugs: New Uses for FDA-approved Prescription Drugs. Simon and Schuster. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-0-7432-8667-1.

- 1 2 3 Michelle A. Clark; Richard A. Harvey; Richard Finkel; Jose A. Rey, Karen Whalen (15 December 2011). Pharmacology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 286,337. ISBN 978-1-4511-1314-3. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Spironolactone". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Oct 24, 2015.

- 1 2 3 NADIR R. FARID; Evanthia Diamanti-Kandarakis (27 February 2009). Diagnosis and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-0-387-09718-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Sica, Domenic A. (2005). "Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Mineralocorticoid Blocking Agents and their Effects on Potassium Homeostasis". Heart Failure Reviews. 10 (1): 23–29. doi:10.1007/s10741-005-2345-1. ISSN 1382-4147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Maron BA, Leopold JA (2008). "Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and endothelial function". Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 9 (9): 963–9. PMC 2967484

. PMID 18729003.

. PMID 18729003. - 1 2 3 4 Takamura, Norito; Maruyama, Toru; Ahmed, Shamim; Suenaga, Ayaka; Otagiri, Masaki (1997). Pharmaceutical Research. 14 (4): 522–526. doi:10.1023/A:1012168020545. ISSN 0724-8741. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Gyorgy Szasz; Zsuzsanna Budvari-Barany (19 December 1990). Pharmaceutical Chemistry of Antihypertensive Agents. CRC Press. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-0-8493-4724-5.

- ↑ Theresa A. McDonagh; Roy S. Gardner; Andrew L. Clark; Henry Dargie (14 July 2011). Oxford Textbook of Heart Failure. OUP Oxford. pp. 403–. ISBN 978-0-19-957772-9. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Friedman, Adam J. (1 October 2015). "Spironolactone for Adult Female Acne". Cutis. 96 (4): 216–217. ISSN 2326-6929. PMID 27141564.

- ↑ Maizes, Victoria (2015). Integrative Women's Health (2 ed.). p. 746. ISBN 9780190214807.

- ↑ "Spironolactone Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ↑ Camille Georges Wermuth (24 July 2008). The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-12-374194-3. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Marshall Sittig (1988). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. William Andrew. p. 1385. ISBN 978-0-8155-1144-1. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Spironolactone". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- 1 2 Hughes BR, Cunliffe WJ (May 1988). "Tolerance of spironolactone". The British Journal of Dermatology. 118 (5): 687–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02571.x. PMID 2969259.

- ↑ Victor R. Preedy (1 January 2012). Handbook of Hair in Health and Disease. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-90-8686-728-8.

- ↑ Loy R, Seibel MM (December 1988). "Evaluation and therapy of polycystic ovarian syndrome". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 17 (4): 785–813. PMID 3143568.

- ↑ HARFMANN, KATYA L.; BECHTEL, MARK A. (March 2015). "Hair Loss in Women". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 58 (1): 185–199. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000081. PMID 25517757.

- 1 2 Batterink, J; Stabler, SN; Tejani, AM; Fowkes, CT (4 August 2010). "Spironolactone for hypertension.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (8): CD008169. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008169.pub2. PMID 20687095.

- 1 2 3 Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL, American College of Cardiology, Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice, Guidelines (Oct 15, 2013). "2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 62 (16): e147–239. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. PMID 23747642.

- ↑ Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme W, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J (1999). "The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators". N Engl J Med. 341 (10): 709–17. doi:10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. PMID 10471456.

- ↑ Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Harty B, Heitner JF, Kenwood CT, Lewis EF, O'Meara E, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, Yang S, McKinlay SM (Apr 10, 2014). "Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.". The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (15): 1383–92. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1313731. PMID 24716680.

- ↑ Pitt B. et. al. (2014). "Spironolactone for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction". N Engl J Med. 370 (15): 1383–1392. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1313731. PMID 24716680.

- ↑ Chatterjee S, Moeller C, Shah N, Bolorunduro O, Lichstein E, Moskovits N, Mukherjee D (2012). "Eplerenone is not superior to older and less expensive aldosterone antagonists". Am. J. Med. 125 (8): 817–25. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.018. PMID 22840667.

- ↑ The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) (2011). "Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-05-27.

- 1 2 Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. (September 2009). "Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 94 (9): 3132–54. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0345. PMID 19509099.

- 1 2 Prior JC, Vigna YM, Watson D (February 1989). "Spironolactone with physiological female steroids for presurgical therapy of male-to-female transsexualism". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 18 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1007/bf01579291. PMID 2540730.

- ↑ Reismann P, Likó I, Igaz P, Patócs A, Rácz K (August 2009). "Pharmacological options for treatment of hyperandrogenic disorders". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (9): 1113–26. doi:10.2174/138955709788922692. PMID 19689407.

- 1 2 Robert S. Haber; Dowling Bluford Stough (2006). Hair Transplantation. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4160-3104-8. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Peter Greaves (12 April 2012). Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies: Interpretation and Relevance in Drug Safety Evaluation. Academic Press. p. 621. ISBN 978-0-444-53861-1. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- 1 2 Andrea Dunaif (19 February 2008). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Current Controversies, from the Ovary to the Pancreas. Humana Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-58829-831-7. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Gökmen O, Senöz S, Gülekli B, Işik AZ (August 1996). "Comparison of four different treatment regimes in hirsutism related to polycystic ovary". Gynecological Endocrinology. 10 (4): 249–55. doi:10.3109/09513599609012316. PMID 8908525.

- ↑ O'Brien RC, Cooper ME, Murray RM, Seeman E, Thomas AK, Jerums G (May 1991). "Comparison of sequential cyproterone acetate/estrogen versus spironolactone/oral contraceptive in the treatment of hirsutism". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 72 (5): 1008–13. doi:10.1210/jcem-72-5-1008. PMID 1827125.

- 1 2 Douglas T. Carrell (12 April 2010). Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Integrating Modern Clinical and Laboratory Practice. Springer. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-1-4419-1435-4. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 Desai; Meena P.; Vijayalakshmi Bhatia & P.S.N. Menon (1 January 2001). Pediatric Endocrine Disorders. Orient Blackswan. p. 167. ISBN 978-81-250-2025-7. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Allan H. Goroll; Albert G. Mulley (27 January 2009). Primary Care Medicine: Office Evaluation and Management of the Adult Patient. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1264. ISBN 978-0-7817-7513-7. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Grigoriou O, Papadias C, Konidaris S, Antoniou G, Karakitsos P, Giannikos L (April 1996). "Comparison of flutamide and cyproterone acetate in the treatment of hirsutism: a randomized controlled trial". Gynecological Endocrinology. 10 (2): 119–23. doi:10.3109/09513599609097901. PMID 8701785.

- 1 2 Seal, L. J.; Franklin, S.; Richards, C.; Shishkareva, A.; Sinclaire, C.; Barrett, J. (2012). "Predictive Markers for Mammoplasty and a Comparison of Side Effect Profiles in Transwomen Taking Various Hormonal Regimens". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 97 (12): 4422–4428. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-2030. ISSN 0021-972X.

- 1 2 H.J.T. Coelingh Benni; H.M. Vemer (15 December 1990). Chronic Hyperandrogenic Anovulation. CRC Press. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-1-85070-322-8.

- ↑ Mary Lee; Archana Desai (2007). Gibaldi's Drug Delivery Systems in Pharmaceutical Care. ASHP. pp. 312–. ISBN 978-1-58528-136-7.

- ↑ Sarfaraz K. Niazi (19 April 2016). Handbook of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Formulations, Second Edition: Volume One, Compressed Solid Products. CRC Press. pp. 470–. ISBN 978-1-4200-8117-6.

- ↑ Sarah H. Wakelin; Howard I. Maibach; Clive B. Archer (1 June 2002). Systemic Drug Treatment in Dermatology: A Handbook. CRC Press. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-1-84076-013-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 960–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bentham Science Publishers (September 1999). Current Pharmaceutical Design. Bentham Science Publishers. p. 711.

More often, mild hypotension (11%), breast enlargement (26%) or dizziness (26%) may occur [53]. In most patients, the above side effects are mild and have no clinical significance. [...] Patients frequently experience menstrual disturbances ranging from 10% to 50% [51,94] with the daily dose of 100mg. The weak progestogenic activity of SP may be responsible for the irregular, anovulatory pattern of menstrual cycles but this issue has not been evaluated adequately. Menstrual disturbances are usually well controlled by concomitant use of oral contraceptives [48].

- ↑ "Spironolactone and endocrine dysfunction". Annals of Internal Medicine. 85 (5): 630–6. November 1976. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-85-5-630. PMID 984618.

- 1 2 Douglas T. Carrell; C. Matthew Peterson (23 March 2010). Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Integrating Modern Clinical and Laboratory Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-1-4419-1436-1.

- ↑ Verhamme K, Mosis G, Dieleman JP, et al. (2006). "Spironolactone and risk of upper gastrointestinal events: population based case-control study". Brit Med J. 333 (7563): 330–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.38883.479549.2F. PMC 1539051

. PMID 16840442.

. PMID 16840442. - ↑ Wandelt-Freerksen E. (1977). "Aldactone in the treatment of sarcoidosis of the lungs". JZ Erkr Atmungsorgane. 149 (1): 156–9. PMID 607621.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jeffrey K. Aronson (2 March 2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Cardiovascular Drugs. Elsevier. pp. 253–258. ISBN 978-0-08-093289-7.

Spironolactone causes breast tenderness and enlargement, mastodynia, infertility, cholasma, altered vaginal lubrica- tion, and reduced libido in women, probably because of estrogenic effects on target tissue.

- 1 2 3 Costas Tsioufis; Roland Schmieder; Giuseppe Mancia (15 August 2016). Interventional Therapies for Secondary and Essential Hypertension. Springer. p. 44. ISBN 978-3-319-34141-5.

Gynecomastia is dose related and reaches almost 50% with high spironolactone doses (>150 mg daily), while it is much less common (5–10%) with low doses (25–50 mg spironolactone daily) [135].

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 777,1087, 1196. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

Spironolactone also is both an antiandrogen and a progestagen, and this explains many of its distressing side effects;” decreased libido, mastodynia, and gynecomastia may occur in 50% or more of men, and menometrorrhagia and and mastodynia may occur in an equally large number of women taking the drug.27

- ↑ Conn, Jennifer J.; Jacobs, Howard S. (1998). "Managing hirsutism in gynaecological practice". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 105 (7): 687–696. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10197.x. ISSN 1470-0328.

Breast tenderness is not uncommon and is recorded in up to 40% of women taking higher doses63.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Donald W. Seldin; Gerhard H. Giebisch (23 September 1997). Diuretic Agents: Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology. Academic Press. p. 630–632. ISBN 978-0-08-053046-8.

The incidence of spironolactone in men is dose related. It is estimated that 50% of men treated with ≥150 mg/day of spironolactone will develop gynecomastia. The degree of gynecomastia varies considerably from patient to patient but in most instances causes mild symptoms. Associated breast tenderness is common but an inconsistent feature.

- 1 2 Side Effects of Drugs Annual: A worldwide yearly survey of new data in adverse drug reactions. Elsevier Science. 1 December 2014. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-444-63391-0.

It is well known that gynecomastia is a side effect of spironolactone in men and occurs in a dose-dependent manner in ~7% of cases with doses of <50 mg per day, and up to 50% of cases with doses of >150 mg per day [40,41].

- 1 2 3 Gordon T. McInnes (2008). Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics of Hypertension. Elsevier. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-444-51757-9.

Spironolactone lacks specificty for mineralocorticoid receptors and binds to both progesterone and dihydrotestosterone receptors. This can lead to various endocrine side effects that can limit the use of spironolactone. In females spironolactone can induce menstrual disturbances, breast enlargement and breast tenderness.78 In men spironolactone can induce gynecomastia and impotence. In RALES gynaecomastia or breast pain was reported by 10% of the men in the spironolactone group and 1% of the men in the placebo group (p<0.001), causing more patients in the spironolactone group than in the placebo group to discontinue treatment, despite a mean spironolactone dose of 26 mg.18

- 1 2 T. Steckler; N. H. Kalin; J. M. H. M. Reul (2005). Handbook of Stress and the Brain: Stress: integrative and clinical aspects. Elsevier. pp. 440–. ISBN 978-0-444-51823-1.

- ↑ Robert G. Lahita (9 June 2004). Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Academic Press. pp. 797–. ISBN 978-0-08-047454-0.

- ↑ Young EA, Lopez JF, Murphy-Weinberg V, Watson SJ, Akil H (2003). "Mineralocorticoid receptor function in major depression". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 60 (1): 24–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.24. PMID 12511169.

- ↑ Heuser I, Deuschle M, Weber B, Stalla GK, Holsboer F (2000). "Increased activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal system after treatment with the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 25 (5): 513–8. doi:10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00006-8. PMID 10818284.

- ↑ Macdonald, J E (2004). "Effects of spironolactone on endothelial function, vascular angiotensin converting enzyme activity, and other prognostic markers in patients with mild heart failure already taking optimal treatment". Heart. 90 (7): 765–770. doi:10.1136/hrt.2003.017368. ISSN 0007-0769.

- ↑ Holsboer, F (2000). "The Corticosteroid Receptor Hypothesis of Depression". Neuropsychopharmacology. 23 (5): 477–501. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7. ISSN 0893-133X.

- ↑ Thai, Keng-Ee; Sinclair, Rodney D (2001). "Spironolactone-induced hepatitis". Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 42 (3): 180–182. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00510.x. ISSN 0004-8380.

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm258786.htm

- ↑ online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/7699#f_adverse-reactions

- 1 2 3 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/012151s062lbl.pdf

- ↑ Aiba M, Suzuki H, Kageyama K, et al. (June 1981). "Spironolactone bodies in aldosteronomas and in the attached adrenals. Enzyme histochemical study of 19 cases of primary aldosteronism and a case of aldosteronism due to bilateral diffuse hyperplasia of the zona glomerulosa". Am. J. Pathol. 103 (3): 404–10. PMC 1903848

. PMID 7195152.

. PMID 7195152. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bertis Little (29 September 2006). Drugs and Pregnancy: A Handbook. CRC Press. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-0-340-80917-4.

- 1 2 3 Peter C. Rubin; Margaret Ramsey (30 April 2008). Prescribing in Pregnancy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-0-470-69555-5.

- 1 2 3 Gerald G. Briggs; Roger K. Freeman; Sumner J. Yaffe (2011). Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1349–. ISBN 978-1-60831-708-0.

- ↑ Uri Elkayam; Norbert Gleicher (23 June 1998). Cardiac Problems in Pregnancy: Diagnosis and Management of Maternal and Fetal Heart Disease. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 353–. ISBN 978-0-471-16358-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Christof Schaefer (2001). Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation: Handbook of Prescription Drugs and Comparative Risk Assessment. Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. 115, 143. ISBN 978-0-444-50763-1.

- 1 2 Sean B. Ainsworth (10 November 2014). Neonatal Formulary: Drug Use in Pregnancy and the First Year of Life. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 486–. ISBN 978-1-118-81959-3.

- ↑ Jonathan Upfal (2006). Australian Drug Guide. Black Inc. pp. 671–. ISBN 978-1-86395-174-6.

- ↑ "Advisory Statement" (PDF). Klinge Chemicals / LoSalt. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2006-11-15. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A (2015). "Low Usefulness of Potassium Monitoring Among Healthy Young Women Taking Spironolactone for Acne". JAMA Dermatology. 151: 941–4. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.34. PMID 25796182.

- ↑ Holsboer, F. The Rationale for Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor (CRH-R) Antagonists to Treat Depression and Anxiety. J. Psychiatr. Res. 33, 181–214 (1999).

- ↑ Otte C, Hinkelmann K, Moritz S, et al. (April 2010). "Modulation of the mineralocorticoid receptor as add-on treatment in depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proof-of-concept study". J Psychiatr Res. 44 (6): 339–46. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.10.006. PMID 19909979.

- ↑ Mostalac-Preciado CR, de Gortari P, López-Rubalcava C (September 2011). "Antidepressant-like effects of mineralocorticoid but not glucocorticoid antagonists in the lateral septum: interactions with the serotonergic system". Behav. Brain Res. 223 (1): 88–98. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.008. PMID 21515309.

- ↑ Juvet T, Gourineni V, Ravi S, Zarich S (September 2013). "Life-threatening hyperkalemia: a potentially lethal drug combination". Connecticut Medicine. 77 (8): 491–493.

- ↑ Garthwaite, Susan M; McMahon, Ellen G (2004). "The evolution of aldosterone antagonists". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 217 (1-2): 27–31. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.005. ISSN 0303-7207.

- 1 2 3 Fagart J, Hillisch A, Huyet J, et al. (September 2010). "A new mode of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism by a potent and selective nonsteroidal molecule". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (39): 29932–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.131342. PMC 2943305

. PMID 20650892.

. PMID 20650892. - ↑ Pelkonen O, Mäenpää J, Taavitsainen P, Rautio A, Raunio H (1998). "Inhibition and induction of human cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes" (PDF). Xenobiotica. 28 (12): 1203–53. doi:10.1080/004982598238886. PMID 9890159.

- ↑ Rigalli JP, Ruiz ML, Perdomo VG, Villanueva SS, Mottino AD, Catania VA (July 2011). "Pregnane X receptor mediates the induction of P-glycoprotein by spironolactone in HepG2 cells". Toxicology. 285 (1-2): 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.015. PMID 21459122.

- ↑ Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, Willson TM, Moore JT, Kliewer SA (September 1998). "The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions". J. Clin. Invest. 102 (5): 1016–23. doi:10.1172/JCI3703. PMC 508967

. PMID 9727070.

. PMID 9727070. - ↑ Christians U, Schmitz V, Haschke M (December 2005). "Functional interactions between P-glycoprotein and CYP3A in drug metabolism". Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 1 (4): 641–54. doi:10.1517/17425255.1.4.641. PMID 16863430.

- ↑ Sorrentino R, Autore G, Cirino G, d'Emmanuele de Villa Bianca R, Calignano A, Vanasia M, et al. (2000). "Effect of spironolactone and its metabolites on contractile property of isolated rat aorta rings.". J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 36 (2): 230–235. doi:10.1097/00005344-200008000-00013. PMID 10942165.

- ↑ Bendtzen, K.; Hansen, P. R.; Rieneck, K. (2003). "Spironolactone inhibits production of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma, and has potential in the treatment of arthritis". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 134 (1): 151158. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02249.x. ISSN 0009-9104.

- ↑ Cheng SC, Suzuki K, Sadee W, Harding BW (October 1976). "Effects of spironolactone, canrenone and canrenoate-K on cytochrome P450, and 11beta- and 18-hydroxylation in bovine and human adrenal cortical mitochondria". Endocrinology. 99 (4): 1097–106. doi:10.1210/endo-99-4-1097. PMID 976190.

- 1 2 Corvol P, Michaud A, Menard J, Freifeld M, Mahoudeau J (July 1975). "Antiandrogenic effect of spirolactones: mechanism of action". Endocrinology. 97 (1): 52–8. doi:10.1210/endo-97-1-52. PMID 166833.

- 1 2 Luthy IA, Begin DJ, Labrie F (November 1988). "Androgenic activity of synthetic progestins and spironolactone in androgen-sensitive mouse mammary carcinoma (Shionogi) cells in culture". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 31 (5): 845–52. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90295-6. PMID 2462135.

- ↑ Térouanne B, Tahiri B, Georget V, et al. (February 2000). "A stable prostatic bioluminescent cell line to investigate androgen and antiandrogen effects". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 160 (1-2): 39–49. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(99)00251-8. PMID 10715537.

- 1 2 Marc A. Fritz; Leon Speroff (20 December 2010). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7817-7968-5. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Attard G, Reid AH, Olmos D, de Bono JS (June 2009). "Antitumor activity with CYP17 blockade indicates that castration-resistant prostate cancer frequently remains hormone driven". Cancer Research. 69 (12): 4937–40. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4531. PMID 19509232.

- ↑ Sundar S, Dickinson PD (2012). "Spironolactone, a possible selective androgen receptor modulator, should be used with caution in patients with metastatic carcinoma of the prostate". BMJ Case Rep. 2012: bcr1120115238. doi:10.1136/bcr.11.2011.5238. PMC 3291010

. PMID 22665559.

. PMID 22665559. - ↑ Flynn T, Guancial EA, Kilari M, Kilari D (2016). "Case Report: Spironolactone Withdrawal Associated With a Dramatic Response in a Patient With Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer". Clin Genitourin Cancer. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2016.08.006. PMID 27641657.

- 1 2 Haynes BA, Mookadam F (August 2009). "Male gynecomastia". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 84 (8): 672. doi:10.4065/84.8.672. PMC 2719518

. PMID 19648382.

. PMID 19648382. - 1 2 3 Rose LI, Underwood RH, Newmark SR, Kisch ES, Williams GH (October 1977). "Pathophysiology of spironolactone-induced gynecomastia". Annals of Internal Medicine. 87 (4): 398–403. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-87-4-398. PMID 907238.

- ↑ Masahashi T, Wu MC, Ohsawa M, et al. (January 1986). "Spironolactone therapy for hyperandrogenic anovulatory women--clinical and endocrinological study". Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 38 (1): 95–101. PMID 3950464.

- ↑ Serafini PC, Catalino J, Lobo RA (August 1985). "The effect of spironolactone on genital skin 5 alpha-reductase activity". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 23 (2): 191–4. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(85)90236-5. PMID 4033118.

- ↑ Wong IL, Morris RS, Chang L, Spahn MA, Stanczyk FZ, Lobo RA (January 1995). "A prospective randomized trial comparing finasteride to spironolactone in the treatment of hirsute women". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 80 (1): 233–8. doi:10.1210/jcem.80.1.7829618. PMID 7829618.

- ↑ Miles RA, Cassidenti DL, Carmina E, Gentzschein E, Stanczyk FZ, Lobo RA (October 1992). "Cutaneous application of an androstenedione gel as an in vivo test of 5 alpha-reductase activity in women". Fertility and Sterility. 58 (4): 708–12. PMID 1426314.

- ↑ Keleştimur F, Everest H, Unlühizarci K, Bayram F, Sahin Y (March 2004). "A comparison between spironolactone and spironolactone plus finasteride in the treatment of hirsutism". European Journal of Endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 150 (3): 351–4. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1500351. PMID 15012621.

- ↑ Schane, H. P.; Potts, G. O. (1978). "Oral Progestational Activity of Spironolactone". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 47 (3): 691694. doi:10.1210/jcem-47-3-691. ISSN 0021-972X.

- ↑ Delyani, John A (2000). "Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists: The evolution of utility and pharmacology". Kidney International. 57 (4): 1408–1411. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00983.x. ISSN 0085-2538.

- ↑ Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM (31 May 2011). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology E-Book: Expert Consult. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 2057. ISBN 978-1-4377-3600-7. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Nakhjavani M, Hamidi S, Esteghamati A, Abbasi M, Nosratian-Jahromi S, Pasalar P (October 2009). "Short term effects of spironolactone on blood lipid profile: a 3-month study on a cohort of young women with hirsutism". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 68 (4): 634–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03483.x. PMC 2780289

. PMID 19843067.

. PMID 19843067. - ↑ Eckhard Ottow; Hilmar Weinmann (9 July 2008). Nuclear Receptors As Drug Targets. John Wiley & Sons. p. 410. ISBN 978-3-527-62330-3. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Anderson E (2002). "The role of oestrogen and progesterone receptors in human mammary development and tumorigenesis". Breast Cancer Research : BCR. 4 (5): 197–201. PMC 138744

. PMID 12223124.

. PMID 12223124. - ↑ Zhou J, Ng S, Adesanya-Famuiya O, Anderson K, Bondy CA (September 2000). "Testosterone inhibits estrogen-induced mammary epithelial proliferation and suppresses estrogen receptor expression". FASEB Journal. 14 (12): 1725–30. doi:10.1096/fj.99-0863com. PMID 10973921.

- ↑ Braunstein GD (September 2007). "Clinical practice. Gynecomastia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (12): 1229–37. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp070677. PMID 17881754.

- ↑ Satoh T, Itoh S, Seki T, Itoh S, Nomura N, Yoshizawa I (October 2002). "On the inhibitory action of 29 drugs having side effect gynecomastia on estrogen production". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 82 (2-3): 209–16. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(02)00154-1. PMID 12477487.

- ↑ Ruggiero RJ, Likis FE (2002). "Estrogen: physiology, pharmacology, and formulations for replacement therapy". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 47 (3): 130–8. doi:10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00233-7. PMID 12071379.

- ↑ Drapier-Faure, Evelyne; Faure, Michel (2006). "Antiandrogens": 124–127. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33101-8_16.

- ↑ Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. Israel Medical Association, National Council for Research and Development. July 1984.

- ↑ Jerry Shapiro (12 November 2012). Hair Disorders: Current Concepts in Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management, An Issue of Dermatologic Clinics. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 186–. ISBN 1-4557-7169-4.

- ↑ Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM (30 November 2015). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 743–. ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7.

- ↑ Sengupta (1 January 2007). Gynaecology For Postgraduate And Practitioners. Elsevier India. pp. 172–. ISBN 978-81-312-0436-8.

- ↑ Bruce R. Carr; Richard E. Blackwell (1998). Textbook of Reproductive Medicine. McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-8385-8893-2.

- ↑ Young EA, Lopez JF, Murphy-Weinberg V, Watson SJ, Akil H (September 1998). "The role of mineralocorticoid receptors in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation in humans". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 83 (9): 3339–45. doi:10.1210/jcem.83.9.5077. PMID 9745451.

- ↑ Otte C, Moritz S, Yassouridis A, et al. (January 2007). "Blockade of the mineralocorticoid receptor in healthy men: effects on experimentally induced panic symptoms, stress hormones, and cognition". Neuropsychopharmacology. 32 (1): 232–8. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301217. PMID 17035932.

- ↑ Campen TJ, Fanestil DD (1982). "Spironolactone: a glucocorticoid agonist or antagonist?". Clin Exp Hypertens A. 4 (9-10): 1627–36. PMID 6128090.

- ↑ Couette B, Marsaud V, Baulieu EE, Richard-Foy H, Rafestin-Oblin ME (1992). "Spironolactone, an aldosterone antagonist, acts as an antiglucocorticosteroid on the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter". Endocrinology. 130 (1): 430–6. doi:10.1210/endo.130.1.1309341. PMID 1309341.

- 1 2 3 International Agency for Research on Cancer; World Health Organization (2001). Some Thyrotropic Agents. World Health Organization. pp. 325–. ISBN 978-92-832-1279-9.

- ↑ Harry G. Brittain (26 November 2002). Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients. Academic Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-12-260829-2. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Overdiek HW, Merkus FW (November 1986). "Influence of food on the bioavailability of spironolactone". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 40 (5): 531–6. doi:10.1038/clpt.1986.219. PMID 3769384.

- ↑ Melander A, Danielson K, Scherstén B, Thulin T, Wåhlin E (July 1977). "Enhancement by food of canrenone bioavailability from spironolactone". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 22 (1): 100–3. PMID 872489.

- ↑ Mellar P. Davis (28 May 2009). Opioids in Cancer Pain. OUP Oxford. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-0-19-923664-0.

- ↑ Blaine T. Smith; Paramount Wellness Institute Brian Luke Seaward, Ph.D.; Visiting Professor University of Oklahoma College of Pharmacy Blaine T Smith (1 November 2014). Pharmacology for Nurses. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 169–. ISBN 978-1-4496-8940-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Agusti, Géraldine; Bourgeois, Sandrine; Cartiser, Nathalie; Fessi, Hatem; Le Borgne, Marc; Lomberget, Thierry (2013). "A safe and practical method for the preparation of 7α-thioether and thioester derivatives of spironolactone". Steroids. 78 (1): 102–107. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2012.09.005. ISSN 0039-128X.

- ↑ Oxford Textbook of Medicine: Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. 2003. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-19-262922-7.

- ↑ Pere Ginés; Vicente Arroyo; Juan Rodés; Robert W. Schrier (15 April 2008). Ascites and Renal Dysfunction in Liver Disease: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. John Wiley & Sons. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-4051-4370-7. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Juruena MF, Pariante CM, Papadopoulos AS, Poon L, Lightman S, Cleare AJ (2013). "The role of mineralocorticoid receptor function in treatment-resistant depression". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 27 (12): 1169–79. doi:10.1177/0269881113499205. PMID 23904409.

- ↑ Colby HD (1981). "Chemical suppression of steroidogenesis". Environ. Health Perspect. 38: 119–27. PMC 1568425

. PMID 6786868.

. PMID 6786868. - ↑ Armanini D, Karbowiak I, Goi A, Mantero F, Funder JW (1985). "In-vivo metabolites of spironolactone and potassium canrenoate: determination of potential anti-androgenic activity by a mouse kidney cytosol receptor assay". Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 23 (4): 341–7. PMID 4064345.

- ↑ Andriulli A, Arrigoni A, Gindro T, Karbowiak I, Buzzetti G, Armanini D (1989). "Canrenone and androgen receptor-active materials in plasma of cirrhotic patients during long-term K-canrenoate or spironolactone therapy". Digestion. 44 (3): 155–62. doi:10.1159/000199905. PMID 2697627.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 https://www.drugs.com/international/spironolactone.html

- 1 2 I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (31 October 1999). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 261–. ISBN 978-0-7514-0499-9.

- 1 2 3 Verma D, Thompson J, Swaninathan S (2016). "Spironolactone blocks Epstein–Barr virus production by inhibiting EBV SM protein function". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113: 3609–3614. doi:10.1073/pnas.1523686113.

External links

- Spironolactone - MedlinePlus - U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Aldactone (spironolactone) patient information leaflet - PDR+