Mahavira

| Mahavira | |

|---|---|

| 24th Jain Tirthankara | |

The idol of Mahavira at Shri Mahavirji, Rajasthan | |

| Other names | Vīr, Ativīr, Vardhamāna, Sanmati, Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta |

| Symbol | Lion |

| Height | 7 cubits (10.5 feet) |

| Age | 72 years |

| Tree | Shala |

| Color | Golden |

| Parents |

|

| Preceded by | Parshvanatha |

| Born | Kundalpur |

| Moksha | Pawapuri |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major figures |

|

Major sects |

|

Festivals |

|

Pilgrimages |

|

|

Mahavira (Mahāvīra), also known as Vardhamāna, was the twenty-fourth and last Jain Tirthankara (Teaching God). Mahavira was born into a royal family in what is now Bihar, India, in 599 BC. At the age of 30, he left his home in pursuit of spiritual awakening, and abandoned worldly things, including his clothes, and became a monk. For the next twelve-and-a-half years, Mahavira practiced intense meditation and severe penance, after which he became kevalī (omniscient).

For the next 30 years, he travelled throughout South Asia to teach Jain philosophy. Mahavira taught that the observance of the vows ahimsa (non-violence), satya (truth), asteya (non-stealing), brahmacharya (chastity) and aparigraha (non-attachment) is necessary to elevate the quality of life. He gave the principle of Anekantavada (pluralism), Syadavada and Nyadavada. The teachings of Mahavira were compiled by Gautama Swami (his chief disciple) and were called Jain Agamas. Most of these Agamas are not available today. Jains believe Mahavira attained moksha (liberation from the cycle of birth and death) at the age of 72.

Biography

In Jainism, a Tirthankara (Maker of the River-Crossing or Teaching God) signifies the founder of a tirtha which means a fordable passage across the sea of interminable births and deaths (called saṃsāra).[1][2] According to the Jain texts, twenty-four Tirthankaras grace each half of the cosmic time cycle. Mahavira was the last Tirthankara of avasarpani (present descending phase).[3][lower-alpha 1] Samantabhadra, an illustrious Digambara monk, who lived in the 2nd century A.D., called the tīrtha of Mahavira by the name Sarvodaya (universal uplift).[5]

Mahavira is often called the founder of Jainism, but this was not the case because the Jain tradition recognizes his predecessors and he is considered the 24th Tirthankara.[6] In addition to that, Parshvanatha (23rd tirthankara) was a historical figure.[7][8][9][10]

Names

According to Jain texts, Mahavira's childhood name was Vardhamāna ("the one who grows"), because of the increased prosperity in the kingdom at the time of his birth.[11] He was called Mahavira ("the great hero") because of the acts of bravery he performed during his childhood.[12][13][14][15] Mahavira was given the title Jīnā ("the victor or conqueror of inner enemies such as attachment, pride and greed"), which later became synonymous with Tirthankara.[16]

Buddhist texts refer to Mahavira as Nigaṇṭha Jñātaputta.[17] Nigaṇṭha means "without knot, tie, or string" and Jñātaputta (son of Natas), refers to his clan of origin as Jñāta or Naya (Prakrit).[16][18][19] He is also known as Sramana (seeker).[12]

Birth

Belonging to Kashyapa gotra,[12][20] Mahavira was born into the royal Kshatriya family of King Siddhartha and Queen Trishala (sister of King Chetaka of Vaishali)[20] of the Ikshvaku dynasty,[21] on the thirteenth day of the rising moon of Chaitra in the Vira Nirvana Samvat calendar in 599 BC.[22][23][24][25] In the Gregorian calendar, this date falls in March or April and is celebrated as Mahavir Jayanti.[26] Traditionally, Kundalpur in the ancient city of Kashtriya Kund Lachhuar is regarded as his birthplace, in the present-day Sikandra Division of Jamui district, Bihar.[27] According to Jainism, after his birth, anointment and abhisheka (consecration)—carried out by Indra on Mount Meru.[28] Most modern historians agree he was born at Kundagrama, now Basokund in Muzaffarpur district[20] in the state of Bihar, India.[29] Jain traditions date Mahavira as living from 599 B.C. to 527 B.C.[23][30] Western historians date Mahavira as living from 480 BC to 408 BC.[31] Some Western scholars suggest Mahavira died around 425 BC.[32] His height was seven cubits (10.5 feet) as per the description given in Aupapatika Sutra.[33]

Early life

As the son of a king, Mahavira had all luxuries of life at his disposal. According to the second chapter of the Śvētāmbara text Acharanga Sutra, both his parents were followers of Parshvanatha and lay devotees of Jain ascetics.[10][11] Jain traditions do not agree about his marital state;[lower-alpha 2] according to the Digambara tradition, Mahavira's parents wanted him to marry Yashoda but Mahavira refused to marry.[35] According to the Śvētāmbara tradition, he was married to Yashoda at a young age and had one daughter, Priyadarshana.[28][20]

Renunciation

At the age of thirty, Mahavira abandoned the comforts of royal life and left his home and family to live an ascetic life in the pursuit of spiritual awakening.[4] He underwent severe penances, meditated under the Ashoka tree and discarded his clothes.[4][13] There is a graphic description of his hardships and humiliation in the Acharanga Sutra.[36][37] According to Kalpa Sūtra, Mahavira spent forty-two monsoons of his ascetic life at Astikagrama, Champapuri, Prstichampa, Vaishali, Vanijagrama, Nalanda, Mithila, Bhadrika, Alabhika, Panitabhumi, Shravasti and Pawapuri.[38]

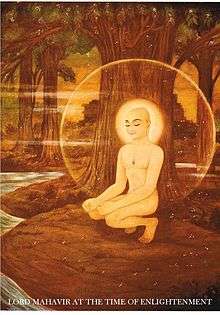

Omniscience

After twelve years of rigorous penance, at the age of 43, Mahavira achieved the state of Kevala Jnana (omniscience or infinite knowledge) under a Sāla tree according to traditional accounts.[39][40] The details of this event are mentioned in Jain texts like Uttar-purāņa and Harivamśa-purāņa.[41] The Acharanga Sutra describes Mahavira as all-seeing. The Sutrakritanga elaborates the concept as all-knowing and provides details of other qualities of Mahavira.[27] Jains believe that Mahavira had the most auspicious body (paramaudārika śarīra) and was free from eighteen imperfections when he attained omniscience.[42]

For thirty years after gaining omniscience, Mahavira travelled throughout in India to teach his philosophy. According to the Jain tradition, Mahavira had 14,000 muni (male ascetics), 36,000 aryika (nuns), 159,000 sravakas (laymen) and 318,000 sravikas (laywomen) as his followers.[43][44] Some of the royal followers included King Srenika (popularly known as Bimbisara) of Magadha, Kunika of Anga and Chetaka of Videha.[38][45]

Moksha (Nirvāṇa)

.jpg)

Jains believe Mahavira attained moksha (liberation from the cycle of birth and death) at the age of seventy-two and his soul is now resting in Siddhashila (abode of the liberated souls). According to Jain texts, Mahavira attained nirvana (final release) at the town of Pawapuri (now in Bihar).[23][46] On the same day, his chief disciple Gautama Swami attained omniscience. According to the Jinasena's Mahapurana, after the nirvana of Tīrthankaras, heavenly beings perform the funeral rites. According to the Pravachanasara, only the nails and hair of Tirthankaras are left behind; the rest of the body is dissolved in the air like camphor.[47][48] Today, a Jain temple called Jal Mandir stands at the place where Mahavira is believed to have attained moksha.[49]

Previous births

Mahavira's previous births are discussed in Jain texts such as the Mahapurana and Tri-shashti-shalaka-purusha-charitra. While a soul undergoes countless reincarnations in the transmigratory cycle of saṃsāra (world), the births of a Tirthankara are reckoned from the time he determined the causes of karma and developed the Ratnatraya. Jain texts discuss twenty-six births of Mahavira before his incarnation as a Tirthankara.[38] As per the texts, Mahavira was born as Marichi, the son of Bharata Chakravartin, in one of his previous births.[28]

Teachings

Jain Agamas

Mahavira's teachings were compiled by his Ganadhara (chief disciple), Gautama Swami. The sacred canonical scriptures had twelve parts.[50] According to Vijay K. Jain, "These scriptures contained the most comprehensive and accurate description of every branch of learning that one needs to know. The knowledge contained in these scriptures was transmitted orally by the teachers to their disciple saints."[50] According to the Digambaras, Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. Later, some learned Āchāryas started to restore, compile and write down the teachings of Lord Mahavira that were the subject matter of Agamas.[51] Āchārya Dharasena, in first century CE, guided two Āchāryas, Āchārya Pushpadant and Āchārya Bhutabali, to write down these teachings. The two Āchāryas wrote on palm leaves, Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama—among the oldest known Digambara Jaina texts. Jain Agamas prescribe five major vratas (vows) that both ascetics and householders have to follow.[52] These ethical principles were preached by Mahavira:[53]

- Ahimsa (Non-violence or Non-injury). Mahavira taught that every living being has sanctity and dignity of its own and it should be respected just as one expects one's own sanctity and dignity to be respected. Ahimsa is formalised into Jain doctrine as the first and foremost vow. According to the Jain text, Tattvarthasutra: "The severance of vitalities out of passion is injury".

- Satya (Truthfulness)—not to lie or speak what is not commendable.[54] According to the Jain text Sarvārthasiddhi: "that which causes pain and suffering to the living is not commendable, whether it refers to actual facts or not".[55]

- Asteya (Non-stealing), which states one should not take anything if not properly given.

- Brahmacharya (Chastity), which stresses steady but determined restraint over yearning for sensual pleasures.

- Aparigraha (Non-attachment)—non-attachment to both inner possessions (liking, disliking) and external possessions like property.

Mahavira's philosophy has eight cardinal (law of trust), three metaphysical (dravya, Jīva and ajiva),[45] and five ethical principles. The objective is to elevate the quality of life.[56] Mahavira said an individual or society should exercise self-restraint to achieve social peace, security and an enlightened society.[57]

Ahiṃsā

Mahavira preached that ahimsa (non-injury) is the supreme ethical and moral virtue.[58] Mahavira taught that no one likes pain and therefore non-injury must cover all living beings.[59] According to Mahatma Gandhi:

No religion in the World has explained the principle of Ahimsa so deeply and systematically as is discussed with its applicability in every human life in Jainism. As and when the benevolent principle of Ahimsa or non-violence will be ascribed for practice by the people of the world to achieve their end of life in this world and beyond. Jainism is sure to have the uppermost status and Lord Mahāvīra is sure to be respected as the greatest authority on Ahimsa.[60][61][62]

Anekantavada

Another fundamental teaching of Mahavira was Anekantavada (pluralism and multiplicity of viewpoints).[63]

Jaina literature

Biographies

Tiloya-paṇṇatti of Yativṛṣabha discusses almost all of the events connected with the life of Mahavira in a form convenient to memorise.[64] Acharya Jinasena's Mahapurāṇa include Ādi purāṇa and Uttara-purāṇa. It was completed by his disciple Acharya Gunabhadra in the 8th century. In Uttara-purāṇa the life of Mahavira is described in three parvans (74–76) in 1818 verses.[65] Vardhamacharitra is a Sanskrit kāvya (poem) that describe the life of Mahavira written by Asaga in 853.[66][67][68]

Kalpa Sūtra is biographies of the Jain Tirthankaras, notably Parshvanatha and Mahavira.

Adoration

- Svayambhustotra by Acharya Samantabhadra is the adoration of twenty-four Tirthankaras. Its eight shlokas (aphorisms) adore the qualities of Mahavira.[69] One such shloka is:

O Lord Jina! Your doctrine that expounds essential attributes required of a potential aspirant to cross over the ocean of worldly existence (Saṃsāra) reigns supreme even in this strife-ridden spoke of time (Pancham Kaal). Accomplished sages who have invalidated the so-called deities that are famous in the world, and have made ineffective the whip of all blemishes, adore your doctrine.[70]

- Yuktyanusasana by Acharya Samantabhadra is a poetic work consisting of sixty-four verses in praise of Mahavira.[71]

- Mahaveerashtak Stotra was composed by Jain poet Bhagchand.[72]

Influence

Mahavira's teachings influenced many personalities. Rabindranath Tagore wrote:

Mahavira proclaimed in India, the message of salvation, that religion is a reality and not a mere social convention, that salvation comes from taking refuge in the true religion and not from observing the external ceremonies of the community, that religion cannot regard any barriers between man and man as an eternal variety. Wonderous to say, this teaching rapidly over topped the barriers of the race abiding instinct and conquered the whole county.— Rabindranath Tagore[61]

A major event is associated with the 2,500th anniversary of the Nirvana of Mahavira in 1974. According to Padmanabh Jaini:[73]

Probably few people in the West are aware that during this Anniversary year for the first time in their long history, the mendicants of the Śvētāmbara, Digambara and Sthānakavāsī sects assembled on the same platform, agreed upon a common flag (Jaina dhvaja) and emblem (pratīka); and resolved to bring about the unity of the community. For the duration of the year four dharma cakras, a wheel mounted on a chariot as an ancient symbol of the samavasaraṇa (Holy Assembly) of Tīrthaṅkara Mahavira traversed to all the major cities of India, winning legal sanctions from various state governments against the slaughter of animals for sacrifice or other religious purposes, a campaign which has been a major preoccupation of the Jainas throughout their history.

In popular culture

Mahavira: The Hero of Nonviolence is an illustrated children’s story based upon the life of Mahavira.[74]

Iconography

Mahavira is usually depicted in a sitting or standing meditative posture with the symbol of a lion beneath him.[75] Every Tīrthankara has a distinguishing emblem that allows worshippers to distinguish similar-looking idols of the Tirthankaras.[76] The lion emblem of Mahavira is usually carved below the legs of the Tirthankara. Like all Tirthankaras, Mahavira is depicted with Shrivatsa[lower-alpha 3] and downcast eyes.[77]

Images

The highest known image of Lord Mahavira (in seated position)

The highest known image of Lord Mahavira (in seated position) Four sided sculpture depicting Mahavira (found during excavation at Kankali Tila, Mathura)

Four sided sculpture depicting Mahavira (found during excavation at Kankali Tila, Mathura) Sculpture depicting Tirthankara Rishabhanatha (left) and Mahavira (right), British Museum, 11th century

Sculpture depicting Tirthankara Rishabhanatha (left) and Mahavira (right), British Museum, 11th century- Temple relief of Mahavira, Seattle Asian Art Museum, 14th century

- Relief depicting Mahavira (Thirakoil, Tamil Nadu)

Mahavira Statue in Cave 32 of Ellora Caves

Mahavira Statue in Cave 32 of Ellora Caves

Temples

- Jal Mandir, Pawapuri

- Shri Mahavirji, Karauli, Rajasthan

- Osian, Jodhpur, Rajasthan

- Muchhal Mahavir Temple, Rajasthan

- Sankighatta, Karnataka

- Lakkundi Jain Temple in Lakkundi

- Rata Mahaveerji, Bijapur, Rajasthan

Lakkundi Jain Temple

Lakkundi Jain Temple- Shri Mahavirji

Osian Jain temple

Osian Jain temple Sankighatta, Karnataka

Sankighatta, Karnataka Jain Mandir, Lachhuar, Bihar

Jain Mandir, Lachhuar, Bihar- Jain temple at Kirti Stambha inside Chittorgarh Fort

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mahavira. |

Notes

- ↑ Heinrich Zimmer: "The cycle of time continually revolves, according to the Jainas. The present "descending" (avasarpini) period was preceded and will be followed by an "ascending" (utsarpini). Sarpini suggests the creeping movement of a "serpent" ('sarpin'); ava- means "down" and ut- means up."[4]

- ↑ On this Champat Rai Jain wrote- "Of the two versions of Mahavira's life — the Swetambara and the Digambara— it is obvious that only one can be true: either Mahavira married, or he did not marry. If Mahavira married, why should the Digambaras deny it? There is absolutely no reason for such a denial. The Digambaras acknowledge that nineteen out of the twenty-four Tirthamkaras married and had children. If Mahavira also married it would make no difference. There is thus no reason whatsoever for the Digambaras to deny a simple incident like this. But there may be a reason for the Swetambaras making the assertion; the desire to ante-date their own origin. As a matter of fact their own books contain clear refutation of the statement that Mahavira had married. In the Samavayanga Sutra (Hyderabad edition) it is definitely stated that nineteen Tirthamkaras lived as householders, that is, all the twenty-four excepting Shri Mahavira, Parashva, Nemi, Mallinath and Vaspujya."[34]

- ↑ a special symbol that mark the chest of a Tirthankara

References

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 181.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1930, p. 3.

- ↑ Sanghvi, Vir (14 September 2013), "Rude Travel: Down The Sages", Hindustan Times

- 1 2 3 Zimmer 1953, p. 224.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 54.

- ↑ Wiley 2009, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 220.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1999, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Sangave 2001, p. 128.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, p. 30.

- 1 2 Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Heehs 2002, p. 93.

- 1 2 von Glasenapp 1999, p. 30.

- ↑ von Dehsen 2013, p. 121.

- ↑ Shanti Lal Jain 1998, p. 50.

- 1 2 Zimmer 1953, p. 223.

- ↑ Winternitz 1993, p. 408.

- ↑ von Dehsen 2013, p. 29.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 von Glasenapp 1999, p. 29.

- ↑ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 313.

- 1 2 3 Zimmer 1953, p. 222.

- ↑ Wiley 2004, p. 134.

- ↑ Shah, Pravin K., Lord Mahavira and Jain Religion,

Jain Study Center of North Carolina

- ↑ Gupta & Gupta 2006, p. 1001.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 Dundas 2002, p. 21.

- ↑ Chaudhary, Pranava K (14 October 2003). "Row over Mahavira's birthplace". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Jainism: The story of Mahavira, London: Victoria and Albert Museum

- ↑ Taliaferro & Marty 2010, p. 126.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 95.

- ↑ Champat Rai Jain 1939, p. 97.

- ↑ Shanti Lal Jain 1998, p. 51.

- ↑ Sen 1999, p. 74.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 von Glasenapp 1999, p. 327.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 30.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1999, p. 30, 327.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 31.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain, ed. (2016-05-13). Ācārya Samantabhadra's Ratnakarandaka-śrāvakācāra. p. 5. ISBN 9788190363990.

- ↑ Heehs 2002, p. 90.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1999, p. 39.

- 1 2 Caillat & Balbir 2008, p. 88.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 22-24.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1999, p. 328.

- ↑ Pramansagar 2008, p. 38–39.

- ↑ "Destinations : Pawapuri". Bihar State Tourism Development Corporation.

- 1 2 Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xi.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xii.

- ↑ Sangave 2006, p. 67.

- ↑ Shah, Umakant Premanand, Mahavira Jaina teacher, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 61.

- ↑ S.A. Jain 1992, p. 197.

- ↑ Chakravarthi 2003, p. 3–22.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 16.

- ↑ Jain & Jain 2002, p. 13.

- ↑ Titze 1998, p. 4.

- ↑ Pandey 1998, p. 50.

- 1 2 Nanda 1997, p. 44.

- ↑ Great Men's view on Jainism,

Jainism Literature Center

- ↑ Jalaj 2011, p. 12.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 45.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 46.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 59.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 19.

- ↑ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 47.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 164–169.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 165.

- ↑ Gokulchandra Jain 2015, p. 84.

- ↑ Mahaveerashtak Stotra

- ↑ Jaini 2000, p. 31.

- ↑ "New Children's Book Mahavira: The Hero of Nonviolence by Wisdom Tales Press", PRLog, 30 June 2014

- ↑ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 192.

- ↑ Zimmer 1953, p. 225.

- ↑ Melton & Baumann 2010, p. 1553.

- ↑ Titze 1998, p. 266.

Sources

- Caillat, Colette; Balbir, Nalini (1 January 2008), Jaina Studies (in Prakrit), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-3247-3

- Chakravarthi, Ram-Prasad (2003), "Non-violence and the other A composite theory of multiplism, heterology and heteronomy drawn from Jainism and Gandhi", Angelaki, 8 (3): 3–22, doi:10.1080/0969725032000154359

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Gupta, K.R.; Gupta, Amita (1 January 2006), Concise Encyclopaedia of India, 3, Atlantic Publishers & Dis, ISBN 978-81-269-0639-0

- Heehs, Peter (2002), Indian Religions: A Historical Reader of Spiritual Expression and Experience, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85065-497-1

- Jain, Champat Rai (1930), Jainism, Christianity and Science, Allahabad: The Indian Press,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Champat Rai (1939), The Change of Heart,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Dr. Gokulchandra (2015), Samantabhadrabhāratī (1st ed.), Budhānā, Muzaffarnagar: Achārya Shāntisāgar Chani Smriti Granthmala, ISBN 978-81-90468879

- Jain, Hiralal; Jain, Dharmachandra (1 January 2002), Jaina Tradition in Indian Thought, ISBN 9788185616841

- Jain, Hiralal; Upadhye, Adinath Neminath (2000) [1974], Mahavira, his times and his philosophy of life, Bharatiya Jnanpith

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Jain, Prof. S.A. (1992) [First edition 1960], Reality (English Translation of Srimat Pujyapadacharya's Sarvarthasiddhi) (Second ed.), Jwalamalini Trust,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Shanti Lal (1998), ABC of Jainism, Bhopal (M.P.): Jnanodaya Vidyapeeth, ISBN 81-7628-000-3

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Vijay K. (2015), Acarya Samantabhadra's Svayambhustotra: Adoration of The Twenty-four Tirthankara, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-7-6,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2000), Collected Papers on Jaina Studies, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-1691-9

- Jalaj, Dr. Jaykumar (2011), W-O Berglin, Peter, ed., The Basic Thought Of Bhagavan Mahavir (Tenth ed.), Hindi Granth Karyalay, ISBN 978-81-88769-41-4

- Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin, eds. (2010), Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, One: A-B (Second ed.), ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3

- Nanda, R. T. (1997), Contemporary Approaches to Value Education in India, Regency Publications, ISBN 978-81-86030-46-2

- Pandey, Janardan (1998), Gandhi and 21st Century, ISBN 9788170226727

- Pramansagar, Muni (2008), Jain Tattvavidya, India: Bhartiya Gyanpeeth, ISBN 978-81-263-1480-5

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2006) [1990], Aspects of Jaina religion (5 ed.), Bharatiya Jnanpith, ISBN 81-263-1273-4

- Sen, Shailendra Nath (1999) [1998], Ancient Indian History and Civilization (2nd ed.), New Age International, ISBN 81-224-1198-3

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-208-X

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Sunavala, A.J. (1934), Adarsha Sadhu: An Ideal Monk (First paperback edition, 2014 ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-62386-6

- Taliaferro; Marty (2010), A dictionary of philosophy of Religion, ISBN 978-1-4411-1197-5

- Titze, Kurt (1998), Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence (2 ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6

- von Dehsen, Christian (13 September 2013), Philosophers and Religious Leaders, Routledge, ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1376-6

- Wiley, Kristi L. (1 January 2004), Historical Dictionary of Jainism, Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-5051-6

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2009), The A to Z of Jainism, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6821-2

- Winternitz, Moriz (1993), History of Indian Literature: Buddhist & Jain Literature, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0265-0

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph, ed., Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Mahāvīra. |

-

Quotations related to Mahavira at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Mahavira at Wikiquote - Harvard Pluralism Project: Jainism