Sobekhotep IV

| Sobekhotep IV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

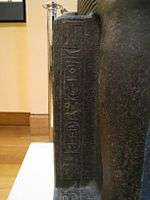

Statue of Sobekhotep IV (Louvre) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | About 10 years (13th Dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Neferhotep I and his coregent Sihathor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Merhotepre Sobekhotep | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Tjan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Haankhef | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Kemi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Possibly tomb S10 at Abydos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV was one of the more powerful Egyptian kings of the 13th Dynasty, who reigned at least eight years. His brothers, Neferhotep I and Sihathor, were his predecessors on the throne, the latter having only ruled as coregent for a few months.

Sobekhotep states on a stela found in the Amun temple at Karnak that he was born in Thebes. The king is believed to have reigned for around 10 years. He is known by a relatively high number of monuments, including stelae, statues, many seals and other minor objects. There are attestations for building works at Abydos and Karnak.

Family

Sobekhotep was the son of the 'god's father' Haankhef and of the 'king's mother' Kemi. His grandfather was the solder of the town's regiment Nehy. His grandmother was called Senebtysy. His wife was the 'king's wife' Tjan. Several children are known. These are Amenhotep and Nebetiunet, both with Tjan as mother. There are three further king's sons: Sobekhotep Miu, Sobekhotep Djadja and Haankhef Iykhernofret. Their mother is not recorded in extant sources.[1]

Royal court

The royal court is also well known from sources contemporaneous with Neferhotep I, providing evidence that Sobekhotep IV continued the politics of his brother in the administration. The Vizier was Neferkare Iymeru. The treasurer was Senebi and the high steward a certain Nebankh.

Royal activities

A stela of the king found at Karnak reports donations to the Amun-Ra temple.[2] A pair of door jambs with the name of the king was found at Karnak, attesting some building work. There is also a restoration inscription on a statue of king Mentuhotep II, also coming from Karnak. From Abydos are known several inscribed blocks attesting some building activities at the local temple[3] The vizier Neferkare Iymeru reports on one of his statues found at Karnak (Paris, Louvre A 125) that he built a canal and a house of millions of years for the king. The statue of the vizier was found at Karnak and might indicate that these buildings were erected there.[4]

For year 6 is attested an expedition to the amethyst mines at Wadi el-Hudi in southernmost Egypt. The expedition is attested via four stelae set up at Wadi el-Hudi.[5] From the Wadi Hammamat comes a stela dated to the ninth regnal year of the king.

He was perhaps buried at Abydos, where a huge tomb (compare: S10) naming a pharaoh Sobekhotep was found by Josef W. Wegner of the University of Pennsylvania just next to the funerary complex of Senusret III of the 12th Dynasty. Although initially attributed to pharaoh Sekhemre Khutawy Sobekhotep I, the style of the burial suggests a date of the tomb under Sobekhotep IV.[6]

Sobekhotep IV's rule over a divided Egypt

While Sobekhotep IV was one of the most powerful 13th dynasty rulers and his control over Memphis, Middle Egypt and Thebes is well attested by historical records, it is believed that he did not rule over a united Egypt. According to the egyptologist Kim Ryholt, the 14th Dynasty was already in control of the eastern Nile Delta at the time.[7]

Alternatively, N. Moeller and G. Marouard argue that the eastern Delta was ruled by the 15th Dynasty Hyksos king Khyan at the time of Sobekhotep IV. Their argument, presented in a recently published article,[8] relies on the discovery of an important early 12th dynasty (Middle Kingdom) administrative building in Tell Edfu, Upper Egypt, which was continuously in use from the early Second Intermediate Period until it fell out of use during the 17th dynasty, when its remains were sealed up by a large silo court. Fieldwork by Egyptologists in 2010 and 2011 into the remains of the former 12th Dynasty building, which was still in use at the time of the 13th dynasty, led to the discovery of a large adjoining hall which proved to contain 41 sealings showing the cartouche of the Hyksos ruler Khyan together with 9 sealings naming the 13th dynasty king Sobekhotep IV.[9] As Moeller, Marouard and Ayers write: "These finds come from a secure and sealed archaeological context and open up new questions about the cultural and chronological evolution of the late Middle Kingdom and early Second Intermediate Period."[10] They conclude, first, that Khyan was actually one of the earlier Hyksos kings and may not have been succeeded by Apophis—who was the second last king of the Hyksos kingdom--and, second, that the 15th (Hyksos) Dynasty was already in existence by the mid-13th Dynasty period since Khyan controlled a part of northern Egypt at the same time as Sobekhotep IV ruled the rest of Egypt as a pharaoh of the 13th dynasty. This analysis and the conclusions drawn from it are questioned by Robert Porter, however, who argues that Khyan ruled much later than Sobekhotep IV. Porter notes that the seals of a pharaoh were used even long after his death, but wonders also wonders whether Sobekhotep IV reigned much later and whether the early Thirteenth Dynasty was much longer than previously thought.[11] In Ryholt's chronology of the Second Intermediate Period, Khyan and Sobekhotep IV are separated by c. 100 years.[7] A similar figure is obtained by Nicolas Grimal.[12] Alexander Ilin-Tomich had a further close look at the pottery associated with the finds of seal impressions and draws parallels to Elephantine where one of the pottery forms of the find appears in a rather late Second Intermediate Period context. Ilin-Tomich concludes that there is no reason to believe that Khyan and Sobekhotep IV reigned at the same time. The level in which the seal impressions were found is later than Sobekhotep IV.[13]

Regardless of which theory is true, either the 14th dynasty or the 15th dynasty already controlled the Delta by the time of Sobekhotep IV.[14]

References

- ↑ K.S.B. Ryholt: The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 BC, Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications, vol. 20. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997, 231

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Eine Stele Sebekhoteps IV. aus Karnak, in MDAIK 24 (1969), 194-200

- ↑ Ryholt: The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 BC, Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications, vol. 20. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997, 349

- ↑ Elisabeth Delange: Catalogue des statues égyptinnes du Moyen Empire, 2060-1560 avant j.-c., Paris 1987 ISBN 2-7118-2-161-7, 66-68

- ↑ Ashraf I. Sadek: The Amethyst Mining Inscriptions of Wadi el-Hudi, Part I: Text, Warminster 1980, ISBN 0-85668-162-8, 46-52, nos. 22-25; Ashraf I. Sadek: The Amethyst Mining Inscriptions of Wadi el-Hudi, Part II: Adittional Texts, Plates, Warminster 1980, ISBN 0-85668-264-0, 5-7, no. 155

- ↑ J. Wegner: A Royal Necropolis at Abydos, in: Near Eastern Archaeology, 78 (2), 2015, p. 70; J. Wegner, K. Cahail: Royal Funerary Equipment of a King Sobekhotep at South Abydos: Evidence for the Tombs of Sobekhotep IV and Neferhotep I?, in JARCE 15 (2015), 123-146

- 1 2 K.S.B. Ryholt: The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 BC, Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications, vol. 20. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997.

- ↑ Nadine Moeller, Gregory Marouard & N. Ayers, Discussion of Late Middle Kingdom and Early Second Intermediate Period History and Chronology in Relation to the Khayan Sealings from Tell Edfu, in: Egypt and the Levant 21 (2011), pp.87-121 online PDF

- ↑ Moeller, Marouard & Ayers, Egypt and the Levant 21, (2011), pp.87-108

- ↑ Moeller, Marouard & Ayers, Egypt and the Levant 21, (2011), p.87

- ↑ Robert M. Porter: The Second Intermediate Period according to Edfu, Goettinger Mizsellen 239 (2013), p. 75-80

- ↑ N. Grimal: Histoire de l'Égypte ancienne, 1988

- ↑ Alexander Ilin-Tomich: The Theban Kingdom of Dynasty 16: Its Rise, Administration and Politics, in: Journal of Egyptian History 7 (2014), 149-150

- ↑ Thomas Schneider, Ausländer in Ägypten während des Mittleren Reiches und der Hyksoszeit I, 1998, pp.158-59

Bibliography

- K.S.B. Ryholt, The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 BC, (Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications, vol. 20. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sebekhotep Khaneferre. |

| Preceded by Neferhotep I |

Pharaoh of Egypt Thirteenth Dynasty |

Succeeded by Sobekhotep V |