Horemheb

| Horemheb | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horemhab, Haremhab | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Detail of a statue of Horemheb, at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1306 BC (most likely) or 1319 BC until 1292 BC (18th Dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ay | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Ramesses I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Amenia, Mutnedjmet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1292 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | KV57 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Memphite Tomb | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Horemheb (sometimes spelled Horemhab or Haremhab and meaning Horus is in Jubilation) was the last pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from either 1319 BC to late 1292 BC,[1] or 1306 to late 1292 BC (since he ruled for 14 years) although he was not related to the preceding royal family and is believed to have been of common birth.

Before he became pharaoh, Horemheb was the commander in chief of the army under the reigns of Tutankhamun and Ay. After his accession to the throne, he reformed the Egyptian state and it was under his reign that official action against the preceding Amarna rulers began. Due to this, he is considered the man who restabilized his country after the troublesome and divisive Amarna Period.

Horemheb demolished monuments of Akhenaten, reusing their remains in his own building projects, and usurped monuments of Tutankhamun and Ay. Horemheb presumably remained childless since he appointed his vizier Paramesse as his successor, who would assume the throne as Ramesses I.[2]

Early career

Horemheb is believed to have originated from Herakleopolis Magna or ancient Hnes (modern Ihnasya el-Medina) on the west bank of the Nile near the entrance to the Fayum since his coronation text formally credits the God Horus of Hnes for establishing him on the throne.[3]

His parentage is unknown but he is believed to have been a commoner. According to the French (Sorbonne) Egyptologist Nicolas Grimal, Horemheb does not appear to be the same person as Paatenemheb (Aten Is Present In Jubilation) who was the commander-in-chief of Akhenaten's army.[4] Grimal notes that Horemheb's political career first began under Tutankhamun where he "is depicted at this king's side in his own tomb chapel at Memphis."[5]

In the earliest known stage of his life, Horemheb served as "the royal spokesman for [Egypt's] foreign affairs" and personally led a diplomatic mission to visit the Nubian governors.[5] This resulted in a reciprocal visit by "the Prince of Miam (Aniba)" to Tutankhamun's court, "an event [that is] depicted in the tomb of the Viceroy Huy."[5] Horemheb quickly rose to prominence under Tutankhamun, becoming commander-in-chief of the army and advisor to the pharaoh. Horemheb's specific titles are spelled out in his Saqqara tomb, which was built while he was still only an official: "Hereditary Prince, Fan-bearer on the Right Side of the King, and Chief Commander of the Army"; the "attendant of the King in his footsteps in the foreign countries of the south and the north"; the "King's Messenger in front of his army to the foreign countries to the south and the north"; and the "Sole Companion, he who is by the feet of his lord on the battlefield on that day of killing Asiatics."[6]

When Tutankhamun died while still a teenager, Horemheb had already been officially designated as the rpat or iry-pat (basically the "hereditary or crown prince") and idnw ("deputy of the king" in the entire land) by the child pharaoh; these titles are found inscribed in Horemheb's then private Memphite tomb at Saqqara which dates to the reign of Tutankhamun since the child king's

... cartouches, although later usurped by Horemheb as king, have been found on a block which adjoins the famous gold of honour scene, a large portion of which is in Leiden. The royal couple depicted in this scene and in the adjacent scene 76, which shows Horemheb acting as an intermediary between the king and a group of subject foreign rulers, are therefore to be identified as Tut'ankhamun and 'Ankhesenamun. This makes it very unlikely from the start that any titles of honours claimed by Horemheb in the inscriptions in the tomb are fictitious.[7]

The title iry-pat (Hereditary Prince) was used very frequently in Horemheb's Saqqara tomb but not combined with any other words. When used alone, the Egyptologist Alan Gardiner has shown that the iry-pat title contains features of ancient descent and lawful inheritance which is identical to the designation for a "Crown Prince."[8] This means that Horemheb was the openly recognised heir to Tutankhamun's throne and not Ay, Tutankhamun's ultimate successor. As the Dutch Egyptologist Jacobus Van Dijk observes:

There is no indication that Horemheb always intended to succeed Tut'ankhamun; obviously not even he could possibly have predicted that the king would die without issue. It must always have been understood that his appointment as crown prince would end as soon as the king produced an heir, and that he would succeed Tut'ankhamun only in the eventuality of an early and/or childless death of the sovereign. There can be no doubt that nobody outranked the Hereditary Prince of Upper and Lower Egypt and Deputy of the King in the Entire Land except the king himself, and that Horemheb was entitled to the throne once the king had unexpectedly died without issue. This means that it is Ay's, not Horemheb's accession which calls for an explanation. Why was Ay able to ascend the throne upon the death of Tut'ankhamun, despite the fact that Horemheb had at that time already been the official heir to the throne for almost ten years?[9]

The aged Vizier Ay sidelined Horemheb's claim to the throne and instead succeeded Tutankhamun, probably because Horemheb was in Asia with the army at the time of Tutankhamun's death. No objects belonging to Horemheb were found in Tutankhamun's tomb, whereas items donated by other high-ranking officials such as Maya and Nakhtmin were found in tomb KV62 by Egyptologists. Further, Tutankhamun's queen, Ankhesenamun, refused to marry Horemheb, a commoner, and so make him king of Egypt.[10] Having pushed Horemheb's claims aside, Ay proceeded to nominate the aforementioned Nakhtmin, who was possibly Ay's son or adopted son, to succeed him rather than Horemheb.[11][12]

After Ay's reign, which lasted for a little over four years, Horemheb managed to seize power, presumably thanks to his position as commander of the army, and to assume what he must have perceived to be his just reward for having ably served Egypt under Tutankhamun and Ay. Horemheb quickly removed Nakhtmin's rival claim to the throne and arranged to have Ay's WV23 tomb desecrated by smashing the latter's sarcophagus, systematically chiselling Ay's name and figure out of the tomb walls and probably destroying Ay's mummy.[13] However, he spared Tutankhamun's tomb from vandalism presumably because it was Tutankhamun who had promoted his rise to power and chosen him to be his heir. Horemheb also usurped and enlarged Ay's mortuary temple at Medinet Habu for his own use and erased Ay's titulary on the back of a 17-foot colossal statue by carving his own titulary in its place.

Internal reform

.jpg)

Upon his accession, Horemheb initiated a comprehensive series of internal transformations to the power structures of Akhenaten's reign, due to the preceding transfer of state power from Amun's priests to Akhenaten's government officials. Horemheb "appointed judges and regional tribunes ... reintroduced local religious authorities" and divided legal power "between Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt" between "the Viziers of Thebes and Memphis respectively."[14]

These deeds are recorded in a stela which the king erected at the foot of his Tenth Pylon at Karnak. Occasionally called The Great Edict of Horemheb,[15] it is a copy of the actual text of the king's decree to re-establish order to the Two Lands and curb abuses of state authority. The stela's creation and prominent location emphasizes the great importance which Horemheb placed upon domestic reform.

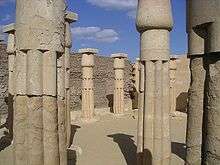

Horemheb also reformed the Army and reorganized the Deir el-Medinah workforce in his 7th Year while Horemheb's official Maya renewed the tomb of Thutmose IV, which had been disturbed by tomb robbers in his 8th Year. While the king restored the priesthood of Amun, he prevented the Amun priests from forming a stranglehold on power, by deliberately reappointing priests who mostly came from the Egyptian army since he could rely on their personal loyalty.[16] Horemheb was a prolific builder who erected numerous temples and buildings throughout Egypt during his reign. He constructed the Second, Ninth and Tenth Pylons of the Great Hypostyle Hall, in the Temple at Karnak, using recycled talatat blocks from Akhenaten's own monuments here, as building material for the first two Pylons.[17]

Because of his unexpected rise to the throne, Horemheb had two tombs constructed for himself: the first – when he was a mere nobleman – at Saqqara near Memphis, and the other in the Valley of the Kings, in Thebes, in tomb KV57 as king. His chief wife was Queen Mutnedjmet, who may have been Nefertiti's younger sister. They did not have any children. He is not known to have any children by his first wife, Amenia, who died before Horemheb assumed power.[18]

Reign length: 26/27 years or 14 years?

_(Vall%C3%A9e_des_Rois_Th%C3%A8bes_ouest)_-6.jpg)

This pharaoh's reign length was long a matter of debate among scholars. Horemheb's highest clearly known dates are a pair of Year 13 and Year 14 wine labels from this king's wine estates which were found in his royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings. It is traditionally believed that Horemheb's highest year-date is likely attested in an anonymous hieratic graffito written on the shoulder of a now fragmented statue from his mortuary temple in Karnak which mentions the appearance of the king himself, or a royal cult statue representing the king, for a religious feast. The ink graffito reads Year 27, first Month of Shemu day 9, the day on which Horemheb, who loves Amun and hates his enemies, entered the temple for this event. (JNES 25[1966], p. 123) Donald Redford, in a BASOR 211(1973) No.37 footnote, observes that the use of Horemheb's name and the addition of a long "Meryamun" (Beloved of Amun) epithet in the graffito suggests a living, eulogised king rather than a long deceased one.

The Egyptologist Rolf Krauss, in a DE 30(1994) paper, argued that this date may well reflect Horemheb's accession where a feast or public holiday was traditionally proclaimed to honour the accession date of a deceased or a current king. Krauss supports his hypothesis with evidence from Ostraca IFAO 1254 which was initially published by Jac Janssen in a BIFAO 84(1984) paper under the title "A Curious Error."[19] The ostraca records the number of days on which an unknown Deir el-Medinah workman was absent from work and covers the period from Year 26 III Peret day 11 to Year 27 II Akhet day 12 before breaking off.[20] The significant fact here is that a Year change occurred in the ostraca from Year 26 to Year 27 around the interval IV Peret day 28 and I Shemu day 13. The Year 27 date of Horemheb is located within this interval and would reflect Horemheb's accession date, Krauss suggests. Ay's accession date occurred somewhere in the month of III Peret.[21] Since Manetho gives Ay a reign of 4 years and 1 month, this ruler would have died sometime around the month of IV Peret or the first half of I Shemu at the very latest. This is precisely the time period noted in Ostraca IFAO 1254. The fact that the ostraca records the case of only one worker rather than an entire group of workmen means the necropolis scribe cannot be presumed – at first glance – to have committed a dating error in altering the unknown king's Year date in the interval between IV Peret 28 and I Shemu 13.

However, it is manifestly obvious from a close study of Manetho that he did not reckon the last month of a king's reign (and his death) in the context of a year from the pharaoh's accession date. That was only done in civil dating on a document or monument. Manetho supplied whole regnal years and then gave the month in which the king died (if he thought he knew it) reckoning from the beginning of that year. For example, the historian (erroneously) thought Hatshepsut must have died in the 9th month of the year because he knew that Thutmose III succeeded on Day 4 of the first month of Summer (the 9th month of the civil calendar), thereby assigning her a reign of 21 years and 9 months. (Marianne Luban)

Janssen, in his original BIFAO 84 paper, noted the curious fact that no known New Kingdom pharaohs who reigned for a quarter of a century including Ramesses II and Ramesses III had their accession date in this time frame and suggests the Year change was an error committed on behalf of the scribe. He then attributed the ostraca to Ramesses III, whose accession date was I Shemu day 26 and expressed his view that the scribe may have inadvertently implemented the Year change two weeks early instead. Janssen also observed that the palaeography of the ostraca suggests a date in the 20th Dynasty partly because it followed the later New Kingdom form of writing and due to its provenance in the Grand Putit region, which features numerous Dynasty 20 ostracas. However, this form of writing is also attested in monuments of Ramesses II and it would, therefore, not be unexpected to find it in a document from the very late 18th Dynasty since the transition from the Early New Kingdom to the Late New Kingdom Form of writing had already occurred prior to the end of Horemheb's reign, as Frank Yurco once noted. Indeed, Janssen's palaeographical reference for his paper–Prof. Georges Posener–himself suggested a date in the 19th Dynasty due to the form of the wsf (absent) and akhet (inundation) text. As Janssen himself writes, a few 19th Dynasty ostracas have been found in the Grand Putit area prior to the 20th Dynasty's intensive exploitation of this region.[22] This does not exclude some late 18th Dynasty work here either. Secondly, both Janssen and Krauss stress in their papers that the relative scarcity of the hieratic text in Ostraca IFAO 1254 precludes a clear dating of the document to Ramesses III's reign and that palaeography, in general, does not give a precise date for a document's creation. Hence, a dating of the ostraca to Horemheb's reign on the basis of the Year change is eminently plausible. On other matters, a damaged wall fragment painting from the Petrie Collection reportedly mentions Horemheb's 15th or 25th Year.

Another important text, the Inscription of Mes, records that a court case decision was rendered in favour of a rival branch of Mes' family in Year 59 of Horemheb.[23] Since the Mes inscription was composed during the reign of Ramesses II when the Amarna-era Pharaohs were struck from the official king-lists, the Year 59 Horemheb date certainly includes the nearly 17-year-long reign of Akhenaten, the 2-year independent reign of Neferneferuaten, the 9-year reign of Tutankhamun and the 4-year reign of Ay. Once all these rulers reigns are deducted from the Year 59 date, Horemheb would still have easily enjoyed a reign of 26–27 years.

At a well known 1987 Conference in Gothenburg, Sweden, Kenneth Kitchen astutely noted that any attempt to explain away the Year 59 Horemheb date as a "scribal error" fails to consider the voluminous listing of court trials and legal setbacks which Mes' family endured in order to win back control over certain valuable lands which had been stolen from his family's line. Indeed, Mes likely ordered the protracted legal dispute, which is presented as a series of court depositions and testimonies of various plaintiffs and witnesses, to be inscribed on his tomb walls in order to create a permanent ('carved in stone') record of his family's ultimately victorious struggle to win back these lands. Mes, hence, could hardly be expected to forget the beginning of his family's legal tribulations in Year 59 of Horemheb. Kitchen also observes in his paper that Horemheb's extensive building projects at Karnak support the theory of a long reign for this Pharaoh and stresses that "a good number of the undated 'late 18th Dynasty' private monuments that are in both Egypt and the world's Museums must, in fact, belong to his reign." Horemheb, hence, probably was assumed to have died after a minimum reign of 27 or, at most, 28 years. Manetho's Epitome assigns a reign length of 4 years and 1 month to Horemheb and this was usually assigned to Ay; however, it is now believed that this figure should be raised by a decade to [1]4 years and 1 month and attributed to Horemheb instead, as Manetho intended.

Horemheb's new reign length

The most recent archaeological evidence from three excavation seasons conducted under G.T. Martin in 2006 and 2007 establishes that Horemheb most likely died after a maximum reign of 14 years, based on a massive hoard of 168 inscribed wine sherds and dockets recently discovered below densely compacted debris in a great shaft (called Well Room E) in this king's royal KV57 tomb. Of the 46 wine sherds with year dates, 14 have nothing but the year date formula, 5 dockets have Year 10+X, 3 dockets have Year 11+X, 2 dockets preserve Year 12+X and 1 docket has a Year 13+X inscription. Meanwhile, 22 dockets "mention Year 13 and 8 have Year 14 [of Horemheb]" but none mention a higher date for Horemheb.[24]

The full texts of the docket readings are identical and read as:

"Year 13. Wine of the estate of Horemheb-meren-Amun, L.P.H., in the domain of Amun. Western River. Chief vintner Ty."[24]

Meanwhile, the Year 14 dockets, in contrast, are all individual and mention specific wines such as "very good quality wine" or, in one case "sweet wine" and the location of the vineyard is identified.[24] A general example is this text on a Year 14 wine docket:

"Year 14, Good quality wine of the estate of Horemheb-meren-Amun, L.P.H., in the domain of Amun, from the wineyard of Atfih, Chief vintner Haty."[24]

Other Year 14 dockets mention Memphis (?), the Western River while their vintners are named as Nakhtamun, [Mer-]seger-men, Ramose and others.[25]

The "quality and consistency of the KV57 dockets strongly suggest that Horemheb was buried in his Year 14, or at least before the wine harvest of his Year 15 at the very latest."[25] This evidence is consistent "with the Horemheb dockets from Deir el-Medina which mention Years 2, 3, 4, 6, 13 and 14, but again no higher dates"... while a docket ascribed to Horemheb from Sedment has Year 12."[26] The lack of dated inscriptions for Horemheb after his Year 14 also explains the unfinished state of Horemheb's royal KV57 tomb--"a fact not taken into account by any of those [scholars] defending a long reign [of 26 or 27 years]. The tomb is comparable to that of Seti I in size and decoration technique, and Seti I's tomb is far more extensively decorated than that of Horemheb, and yet Seti managed to virtually complete his tomb within a decade, whereas Horemheb did not even succeed in fully decorating the three rooms he planned to have done, leaving even the burial hall unfinished. Even if we assume that Horemheb did not begin the work on his royal tomb until his Year 7 or 8, ... it remains a mystery how the work could not have been completed had he lived on for another 20 or more years."[27] Therefore, Horemheb's reign has been determined and accepted today by most scholars to be 14 years and 1 month—Manetho had assigned him a reign of 4 years in his Epitome and 1 month—based on the clear evidence of the wine jar labels and the lack of dates beyond his Year 14 but this figure should be raised by a decade. As for the Year 27 hieratic graffito at Horemheb's Funerary temple at Medinet Habu and the Year 59 date from the inscription of Mes, Van Dijk argues that the first date likely inaugurated a statue of Horemheb during Year 27 of Ramesses II or III in Horemheb's temple while the latter date of Mes "can hardly be taken seriously, and indeed is not taken at face value by even the staunchest supporters of a long reign" for Horemheb since there was no standard Egyptian practise of including the years of all the rulers between Amenhotep III and Horemheb as Wolfgang Helck makes clear.[28]

Succession

_(Vall%C3%A9e_des_Rois_Th%C3%A8bes_ouest)_-4.jpg)

Under Horemheb, Egypt's power and confidence were once again restored after the internal chaos of the Amarna period; this situation set the stage for the rise of the 19th Dynasty under such ambitious Pharaohs as Seti I and Ramesses II. Horemheb is believed to have unsuccessfully attempted to father an heir to the throne since the mummy of his second wife was found with a fetus in it. Geoffrey Martin in his excavation work at Saqqara states that the burial of Horemheb's second wife Mutnedjmet was located at the bottom of a shaft to the rooms of Horemheb's Saqqara tomb. He notes that "a fragment of an alabaster vase inscribed with a funerary text for the chantress of Amun and King's Wife, Mutnodjmet, as well as pieces of a statuette of her [was found here] ... The funerary vase in particular, since it bears her name and titles would hardly have been used for the burial of some other person."[29]

Expert analysis subsequently showed that the bones represented part of the skull and other portions of the body, including the pelvis, of an adult female who had given birth several times. Furthermore, she had lost all her teeth early in life, and was therefore only able to eat soft foods for much of the time. She died in her mid-forties, perhaps in childbirth, for with her bones were those of a foetus or newborn child. The [tomb] plunderers had evidently dragged the two mummies, mother and child, from the burial chamber below, and broken them open in the pillared hall above. The balance of probability, taking into account the evidence of the objects inscribed for Mutnodjmet, is that the adult bones are those of the queen herself and that she died in attempting to provide her husband the Pharaoh with an heir to the throne.[29]

Since Horemheb remained childless, he appointed his Vizier, Paramesse, to succeed him upon his death, both to reward Paramesse's loyalty and because the latter had both a son and grandson to secure Egypt's royal succession. Paramesse employed the name Ramesses I upon assuming power and founded the 19th Dynasty of the New Kingdom. While the decoration of Horemheb's KV57 tomb was still unfinished upon his death, this situation is not unprecedented: Amenhotep II's tomb was also not fully completed when he was buried, even though this ruler enjoyed a reign of 26 Years.

Fictional representations

Film

- He was portrayed by Victor Mature in The Egyptian (1954), the film adaptation of Mika Waltari's bestselling novel.

Television

- He was portrayed by British actor Nonso Anozie in the 2015 mini-TV series Tut which aired on Spike in the US, and on Channel 5 in the UK.

Music

Horemheb is a character in the opera Akhnaten by Philip Glass; he is sung by a baritone.

Literature

- Horemheb is a major character in Nick Drake's trilogy of mystery novels, The Book of the Dead, Tutankhamun and The Book of Chaos.

- Horemheb is a major character in P. C. Doherty's trilogy of historical novels, An Evil Spirit Out of the West, The Season of the Hyaena and The Year of the Cobra.

- Horemheb is a major character in Pauline Gedge's historical novel The Twelfth Transforming.

- Horemheb is a major character in Katie Hamstead's trilogy, Kiya: Hope of the Pharaoh, Kiya: Mother of the King and Kiya: Rise of a New Dynasty.

- Horemheb is a minor character in the novel Nefertiti by Michelle Moran.

- Horemheb appears as a major character in Lynda Suzanne Robinson's Lord Meren series of Egyptian mysteries.

- Horemheb is a minor character in Chie Shinohara's Japanese graphic novel, Red River, centered around ancient Anatolia and ancient Egypt.

- Horemheb is a major character in Mika Waltari's historical fiction international bestseller, Sinuhe, The Egyptian.

- Horemheb is a major character, originally named Kaires, in Allen Drury's two novels about the Amarna period in Egypt, A God Against the Gods (Doubleday, July 1976, ISBN 0-385-00199-1) and Return to Thebes (Doubleday, Feb. 1977, ISBN 0-385-04199-3), both reprinted by WordFire Press in 2015.

References

- ↑ Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss & David Warburton (editors), Ancient Egyptian Chronology (Handbook of Oriental Studies), Brill: 2006, p.493 Chronology table

- ↑ "Ramesses". carlos.emory.edu.

- ↑ Alan Gardiner, "The Coronation of King Haremhab," JEA 39 (1953), pp.14, 16 & 21

- ↑ "Virtual Egyptian Museum - The Full Collection". virtual-egyptian-museum.org.

- 1 2 3 Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell:1992, p. 242.

- ↑ John A. Wilson "Texts from the Tomb of General Hor-em-heb" in Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET) relating to the Old Testament, Princeton Univ. Press, 2nd edition, 1955. pp.250-251

- ↑ The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis: The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis. Historical and Iconographical Studies by Jacobus Van Dijk, University of Groningen dissertation. Groningen 1993. "Chapter One: Horemheb, Prince Regent of Tutankh'amun," pp.17-18 (online: pp.9-10)

- ↑ Alan Gardiner, The Coronation of King Haremhab, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 39 (1953), pp.13-31

- ↑ The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis: The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis. Historical and Iconographical Studies by Jacobus Van Dijk, University of Groningen dissertation. Groningen 1993. "Chapter One: Horemheb, Prince Regent of Tutankh'amun," pp.48-49 (online: pp.40-41)

- ↑ The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis: The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis. Historical and Iconographical Studies by Jacobus Van Dijk, Ibid., pp.50-51 & 56-60 (online: pp.42-43 & 48-52)

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck, Urkunden der 18. Dynastie: Texte der Hefte 20-21 (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1984), pp.1908-1910

- ↑ The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis: The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis. Historical and Iconographical Studies by Jacobus Van Dijk, University of Groningen dissertation. Groningen 1993. "Chapter One: Horemheb, Prince Regent of Tutankh'amun," pp. 59-62 (online: pp. 51-54)

- ↑ Tomb 23 in the western annex of the Valley of the Kings; see Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyph Texts, Reliefs and Parts, vol. 1, part 2, (Oxford Clarendon Press:1960), pp. 550-551

- ↑ Nicolas Grimal, op.cit., p.243

- ↑ "The Great Edict of Horemheb". reshafim.org.il.

- ↑ Peter Clayton, Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1994. p.137

- ↑ Grimal, op.cit., pp.243, 303

- ↑ Joyce Tyldesley, Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt, Thames & Hudson 2006. p.140

- ↑ Rolf Krauss, "Nur ein kurioser Irrtum oder ein Beleg für die Jahr 26 und 27 von Haremhab?" Discussions in Egyptology 30, 1994, pp.73-85

- ↑ Jac Janssen, A Curious Error, BIFAO 84(1984), pp.303-306.

- ↑ J. von Beckerath, Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten, Mainz, (1997), p.201

- ↑ Janssen, op. cit., p.305

- ↑ "Inscription of Mes". reshafim.org.il.

- 1 2 3 4 Jacobus Van Dijk, New Evidence on the Length of the Reign of Horemheb, Journal of the American Research Centre in Egypt (JARCE) 44, 2008, p.195

- 1 2 Van Dijk, JARCE 44, p.196

- ↑ Van Dijk, JARCE 44, pp.197-98 which quotes papers by G. Nagel, La ceramique du Nouvel Empire a Deir Medineh (Cairo) 1938, 15:6 (Year 2); Y. Koenig, Catalogues des etiquettes de jarres hieratiques de Deir el Medineh (Cairo, 1979-1980), nos. 6299 (Year 3), 6295 (Year 4), 6403 (Year 6), 6294 (Year 13) 6345 (Year 14) & G.T. Martin, "Three Objects of New Kingdom Date from the Memphite Area and Sidmant. 3. An inscribed amphora from Sidmant," in J. Baines, et al., Pyramid Studies and Other Essays presented to I.E.S. Edwards (London, 1988), 118-120, pl.21.

- ↑ Van Dijk, JARCE 44, p.198

- ↑ Helck, Urkunden IV, 2162 & Van Dijk, JARCE 44, pp.198-99

- 1 2 G. Martin, The Hidden Tombs of Memphis, Thames & Hudson (1991), pp.97-98

Bibliography

- Alan Gardiner, The Inscription of Mes: A Contribution to Egyptian Juridical Procedure, Untersuchungen IV, Pt. 3 (Leipzig: 1905).

- Jürgen von Beckerath, Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägypten, MÄS 46, Philip Von Zabern, Mainz: 1997

- Nicholas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Books: 1992

- K.A. Kitchen, The Basis of Egyptian Chronology in relation to the Bronze Age," Volume 1: pp. 37-55 in "High, Middle or Low?: Acts of an International Colloquium on absolute chronology held at the University of Gothenburg 20–22 August 1987." (ed: Paul Aström).

External links

![]() Media related to Horemheb at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Horemheb at Wikimedia Commons