Dedumose II

| Dedumose II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dudimose, Tutimaios | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

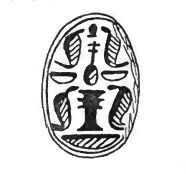

Stele CG 20533 of Djedneferre Dedumose II from Gebelein.[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | some time between 1588 BC and 1582 BC (Ryholt) (16th Dynasty (Ryholt, Baker) or 13th Dynasty (von Beckerath, Schneider, Franke)) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Dedumose I? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Djedankhre Montemsaf? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Dedumose I? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Djedneferre Dedumose II was a native Ancient Egyptian pharaoh during the Second Intermediate Period. According to egyptologists Kim Ryholt and Darrell Baker, he was a ruler of the Theban 16th Dynasty.[3][4] Alternatively, Jürgen von Beckerath, Thomas Schneider and Detlef Franke see him as a king of the 13th Dynasty.[5][6][7][8]

Dating issues

Williams and other place Dedumose as the last king of Egypt's 13th Dynasty. Precise dates for Dedumose are unknown, but according to the commonly accepted Egyptian chronology his reign probably ended around 1690 BC.[9]

There have been attempts by the revisionist historians Immanuel Velikovsky and David Rohl to identify him as the Pharaoh of the Exodus, much earlier than the mainstream candidates.[10]

Attestations

Djedneferre Dedumose II is known from a stela originally from Gebelein which is now in the Cairo Museum (CG 20533).[12] On the stela Dedumose claims to have been raised for kingship, which may indicate he is a son of Dedumose I, although the statement may also merely be a form of propaganda. The martial tone of the stela probably reflects the constant state of war of the final years of the 16th Dynasty, when the Hyksos invaded its territory:[13]

| “ | The good god, beloved of Thebes; The one chosen by Horus, who increases his [army], who has appeared like the lightning of the sun, who is acclaimed to the kingship of both lands; The one who belongs to shouting. | ” |

Ludwig Morenz believes that the above excerpt of the stele, in particular "who is acclaimed to the kingship", may confirm the controversial idea of Eduard Meyer that certain pharaohs were elected to office.[13]

As Josephus' Tutimaios

Attempts have been made to link Dedumose to the story of Tutimaios[14][15] or Timaios, his conflict with the Hyksos and his fall, as told by the historian Josephus.[16] However, the link between Dedumose and Tutimaios is tenuous at best and not supported by linguistic (Tutimaios is more likely derived from Djehutymose) or historical facts.[17]

In Rohl's revised chronology

David Rohl's 1995 A Test of Time attempted to change views on Egyptian history by shortening the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt by almost 300 years. As a by-result the synchronisms with the biblical narrative have changed, making the 13th Dynasty pharaoh Djedneferre Dedumose (Dedumesu, Tutimaos, Tutimaios) the pharaoh of the Exodus.[18] Rohl's theory, however, has failed to find support among most scholars in his field.[19]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dedumose Djedneferre. |

References

- ↑ Hans Ostenfeldt Lange (1863-1943); Maslahat al-Athar; Heinrich Schäfer, (1868-1957) : Catalogue General des Antiquites du Caire: Grab- und Denksteine des Mittleren Reichs im Museum von Kairo, Tafel XXXVIII, (1902) available copyright-free online, see CG 20533 p. 97 of the online reader

- ↑ Hans Ostenfeldt Lange (1863-1943); Maslahat al-Athar; Heinrich Schäfer, (1868-1957) : Catalogue General des Antiquites du Caire: Grab- und Denksteine des Mittleren Reichs im Museum von Kairo, Tafel XXXVIII, (1902) available copyright-free online, see CG 20533 p. 97 of the online reader

- ↑ Ryholt, K. S. B. (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c. 1800 - 1550 BC. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-7289-421-0. excerpts available online.

- ↑ Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I - Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC, Stacey International, ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9, 2008

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath: Untersuchungen zur politischen Geschichte der Zweiten Zwischenzeit in Ägypten, Glückstadt, 1964

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägyptens, Münchner Ägyptologische Studien 46, Mainz am Rhein, 1997

- ↑ Thomas Schneider: Ancient Egyptian Chronology - Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, And David a. Warburton, available online, see p. 187

- ↑ Detlef Franke: Das Heiligtum des Heqaib auf Elephantine. Geschichte eines Provinzheiligtums im Mittleren Reich, Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens. vol. 9. Heidelberger Orientverlag, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-927552-17-8 (Heidelberg, Universität, Habilitationsschrift, 1991), see p. 77-78

- ↑ Chris Bennett: A Genealogical Chronology of the Seventeenth Dynasty, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 39 (2002), pp. 123-155

- ↑ Pharaohs and Kings by David M. Rohl (New York, 1995). ISBN 0-609-80130-9

- ↑ Flinders Petrie: A History of Egypt - vol 1 - From the Earliest Times to the XVIth Dynasty (1897), available copyright-free here, p. 245, f. 148

- ↑ W. V. Davies, The Origin of the Blue Crown, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 68, (1982), pp. 69-76

- 1 2 Ludwig Morenz and Lutz Popko: A companion to Ancient Egypt, vol 1, Alan B. Lloyd editor, Wiley-Blackwell, p. 106

- ↑ Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Blackwell Books. ISBN 9780631174721., p. 185

- ↑ Hayes, William C. (1973). "Egypt: from the death of Ammenemes III to Seqenenre II". In Edwards, I.E.S. The Cambridge Ancient History (3rd ed.), vol. II, part 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–76. ISBN 0 521 082307., p. 52

- ↑ Josephus, Flavius (2007). Against Apion – Translation and commentary by John M.G. Barclay. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 978 90 04 11791 4., I:75-77

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck, Eberhard Otto, Wolfhart Westendorf, Stele - Zypresse: Volume 6 of Lexikon der Ägyptologie, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1986.

- ↑ Rohl, David (1995). "Chapter 13". A Test of Time. Arrow. pp. 341–8. ISBN 0-09-941656-5.

- ↑ Chris Bennett: Temporal Fugues, Journal of Ancient and Medieval Studies XIII (1996). Available at

| Preceded by Dedumose I? |

Pharaoh of Egypt Sixteenth Dynasty |

Succeeded by Djedankhre Montemsaf? |