Shaunavon, Saskatchewan

| Shaunavon | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

|

Grain elevators by the railway track | |

| Nickname(s): Bone Creek Basin, Boomtown, | |

| Motto: Oasis of the Prairies | |

Shaunavon  Shaunavon | |

| Coordinates: 49°39′04″N 108°24′43″W / 49.651°N 108.412°W | |

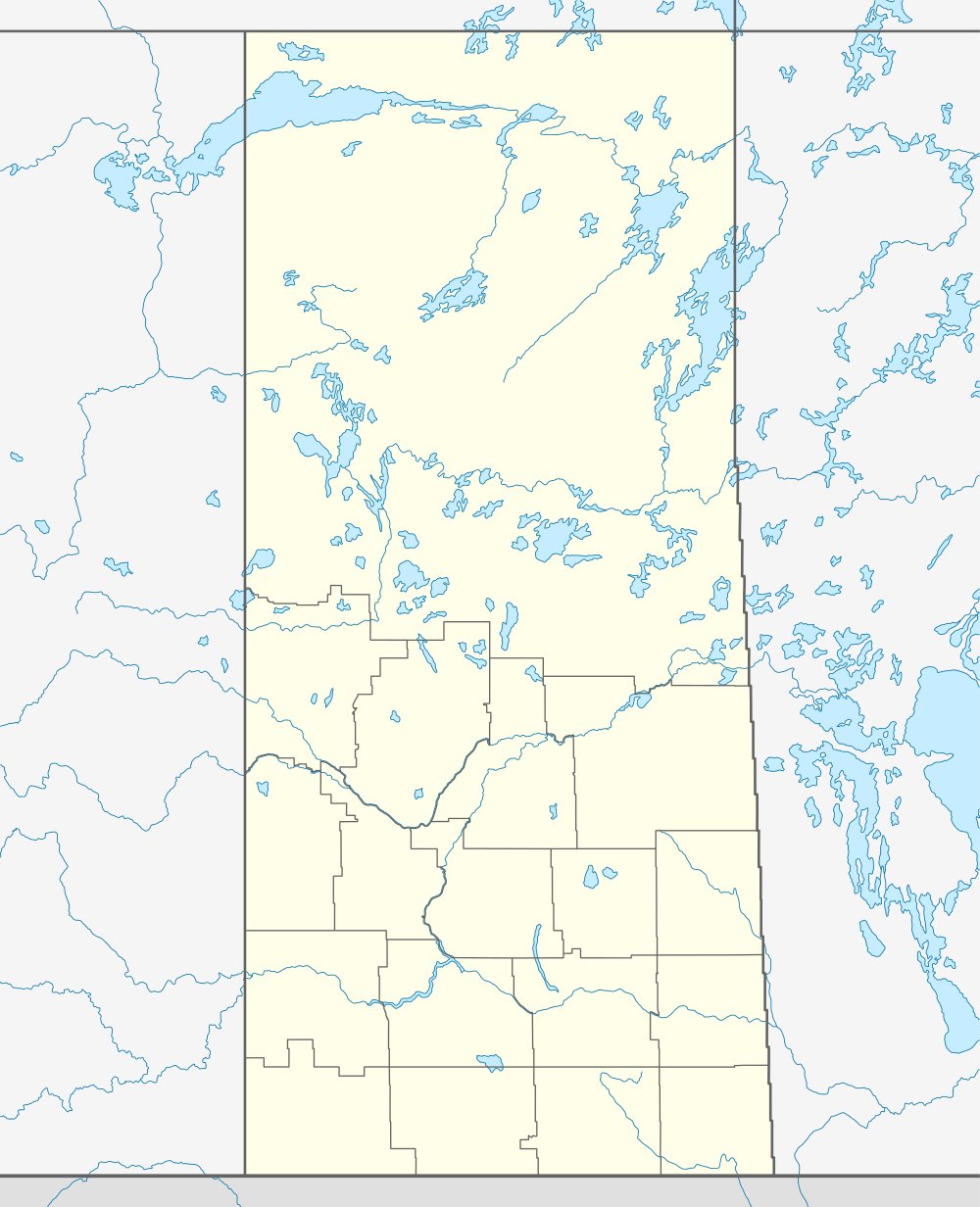

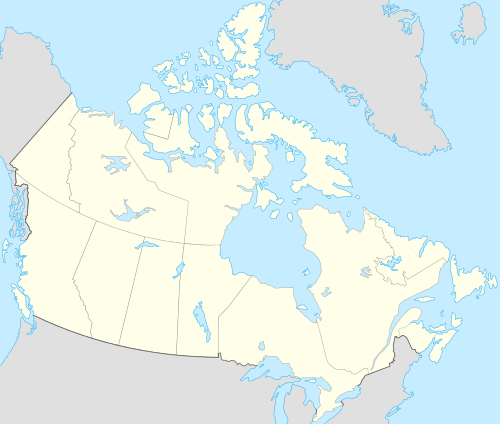

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Saskatchewan |

| Region | Saskatchewan |

| Census division | 4 |

| Rural Municipality | Grassy Creek |

| Post office established | 1913 |

| Incorporated (Village) | 1913 |

| Incorporated (Town) | 1914 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Sharon J. Dickie |

| • Administrator | Jay Meyer |

| • Governing body | Shaunavon Town Council |

| • MP | David L. Anderson |

| • MLA | Wayne Elhard |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.10 km2 (1.97 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 916 m (3,005 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,756 |

| • Density | 344.2/km2 (891/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CST |

| Postal code | S0N 2M0 |

| Area code(s) | 306 |

| Highways |

Redcoat Trail Highway 37 Highway 722 |

| Industries |

Agriculture Oil Tourism |

| Climate | Dfb |

| Website |

www |

| [2][3][4][5] | |

The town of Shaunavon is located in southwest Saskatchewan at the junction of Highways 37 and 13. It is 110 kilometres from Swift Current, 163 kilometres from the Alberta border and 74 kilometres from the Montana border. Shaunavon was established in 1913 along the Canadian Pacific Railway line.

The town has several nicknames including Bone Creek Basin, Boomtown, and Oasis of the Prairies. The latter name is derived from the park located in the centre of town.[6] The Shaunavon Formation, a stratigraphical unit of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin is named for the town.

History

Pre-colonial History

Pre-contact & early European contact (Shaunavon prior to 1913)

Before 1000 CE, only two distinct technological traditions were present on the Canadian plains. Archaeologists refer to them as the Besant and Avonlea phases. Besant sites first appeared on the eastern plains of Minnesota about 200 BCE. Makers of Avonlea technology first appeared in the arid southern plains of Alberta and Saskatchewan three centuries later.[7]

There is no physical or documentary evidence of a widespread and deadly “disorder” among game animals in the archaeological record, but by the 1760s HBC (Hudson Bay Company) employees were reporting game shortages along the North Saskatchewan River. Archaeological studies on the northern Great Plains have uncovered the influence of the fur trade from as early as the 1670s. Recognizing the arrival and impact of epidemic disease known as “virgin soil epidemic”, historical experience of indigenous populations.[8]

Aboriginal traders periodically suffered from breakdown of the precarious link between Europe and Hudson Bay. When the French controlled Hudson Bay, from 1680 to 1713, they were unable to deliver supplies to the region for four years in succession.[9]

The complex interaction of the global economy and the spread of disease are illustrated by the virgin soil outbreak of smallpox amongst the Niitsitapi of Southern Alberta prior to 1750. The Cree people of the Saskatchewan parklands did not experience their virgin soil outbreak of smallpox until the 1780s.[10]

Gradually fur traders began to come into the territory. In 1871, a severe drought brought near starvation to the whole area. Wild animals migrated in search of food and water and the white men in the area lived on gophers, barley and potatoes. The Indians had even less. Long before the settlers or fur traders ever dreamed of the Cypress Hills, the land in the southwestern corner of Saskatchewan was inhabited by bands of nomadic Indians. There were the Assiniboine’s, right in the Cypress Hills, the Cree’s on the flat plains to the east of them, and the Blackfeet toward the west, in the foothills of the Rockies.[11]

French settlements had developed in the southwestern region. In 1908–10, the community of Valroy (later Dollard, named after Adam Dollard des Ormeaux, a Quebec hero in 1660), 70 km west of Cadillac, was established by settlers from Quebec and various French settlements on the prairies as well as by some Belgian families. Today their descendants number about 500 in the predominantly French community of Dollard, where the parish of Ste-Jeanne-d'Arc was founded in 1908, in the nearby towns of Eastend and Shaunavon, and in the surrounding rural districts at the eastern end of the Cypress Hills.[12]

By 1906 ranching had become firmly established and was flourishing in South-Western Saskatchewan. However, the terrible winter of 1906- 1907 ended the golden years of the cattle kingdom. Extreme cold, blizzards and deep snow took a terrible toll of cattle and sheep wintering out. The most notable development in ranching after the rebellion was the founding of a ranching empire by Sir John Lister-Kaye. In January 1887, this English entrepreneur purchased 100,000 acres of land equally distributed among ten sites along Canadian pacific west of Moose Jaw. Five of the sites—Rush Lake, Swift Current, Gull Lake, Crane Lake, and Kincorth—were in southwest Saskatchewan.[13]

Three explanations for the establishment of series of French bloc settlements across the prairies after the North-West Resistance can be suggested. First, the immigration of large numbers of French-speaking farmers, Second, the establishment of specifically French bloc settlements, Third, most of the French settlements resulted from a planned attempt to maintain a significant proportion of French-speakers in the west. Pères Royer and Gravel, in 1906–10, established most of those in the south-central and southwestern regions.[12]

In the early days a fine spirit of comradeship and neighborliness prevailed among the pioneer settlers, perhaps because they felt they were all equal—no one had anything. Together they experienced the rigors of wrestling a home from the wilderness. However, they found the new life a thrilling experience, they found the wide-open spaces of the plains exhilarating, and the country held nothing but promise for ambitious young people.[14]

In spite of severe drought and hard winters the land was excellent for grazing cattle. It was vast land for the big time ranchers. In the late 1800s big wagon trains rolled northward—wagon drawn by horses and oxen rumbling and creaking over the plains. Early ranchers in the district were Beardy Porce, Harry Otterson, Buck Hardin, Hugo Maguire, Wilson McGowe and Bill Huff. Among some of the early pioneer settlers who lived in this immediate area of Shaunavon were Bill Boyle, the Hifners, Thomas NcNelly, and the Marshalls. Pat and Bill Ganley homesteaded the actual town site.[15]

Métis in Shaunavon

Early history and economy.

The presence of Métis in the area around Shaunavon starts in the late 1870s, when discrimination in Manitoba forced them to move to the area near Willow Bunch and Wood Mountain.[16] By 1885, a census identified 48 French-Métis around the Swift Current area. However, most Métis were of nomadic nature, and an exact number is hard to determine. Métis population was also enriched by the presence of people from Europeans in the areas of Swift Current and Maple Creek: according to the same 1885 census, there were a total of 93 and 123 Europeans in those areas, respectively.[17]

One of the main reasons that kept the Métis in areas near current day Shaunavon was the presence of buffalo. Hunting represented a considerable activity for the group, both economically and for their regular life. The trail used by the Métis from Wood Mountain to the Cypress Hills (in which Shaunavon is located) represented one of the most important routes for bison hunting, and it also represented the quick spread of the group to the west in the 1860s and 1870s.[18] However, it is also known that the Métis in the area carried out other activities: until the connection to Saskatoon via railway, the freighting of goods from Swift Current to Battleford using red river carts represented an important source of living, even though the earnings for the freighters started as low as three cents per pound.[19]

Cultural and social issues.

Métis faced several social issues in the area near Shaunavon. Not only did they face economic difficulties as a result of the federal government’s preferences for settlers, but they also had to face racism from these settlers, which made the economic crisis an even worse scenario to handle for the group.[20]

Métis culture was attacked by these newcomers, who saw the group’s gatherings as meetings for plotting attacks against them.[20] Such suspicions led to investigations by the North-West Mounted Police, who determined that Métis gathering responded to celebrations and traditional events. However, already in the 1900s, racist issues continued in the form of insult and attacks against Métis in schools in areas such as Lac Pelletier or Ponteix.[21] Catholicism was an important part of Métis culture in this area; however it is recorded that some families would keep the traditions carried out by their First Nations ancestors. Catholic ceremonies were most frequently ministered by Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. Two important priests for the Métis in the area were Fathers Joseph Lestand and Jules Decorby, who ministered around the Cypress Hills and Eastend.[22] Such was the importance of the priests that chapels were built quickly in towns as soon as it was known that they would be visited by a priest.

Contribution in rebellions.

With the rise of rebellions between First Nations and Métis against the Canadian government, people that fled Red River gained importance and supported the rebels. In the area of Shaunavon and nearby, there was an important support to Sitting Bull and the Sioux, where they found refuge after the victory at Little Big Horn. In this area, the Sioux found Jean Louis Légaré, who had been in the area as a trader, and who later became a very important mediator between them and the Canadian and American governments during the negotiations in 1876 and 1877.[23]

Movement to the United States.

Given that the border between the United States and Canada was unclear and unprotected until 1873 and 1874, Saskatchewan Métis travelled between the province and the territory that comprises the state of Montana. During the 1920s, the government of the United States recognized the origin of a number of their Métis to be “half breeds, half Canadian and Cree”. These half breeds, started in immigrants Antoine Azure and Antoined Glaude, were Chippewa and Pembina descendants.[24]

Aboriginal Peoples in Shaunavon Area

Atsina

In the 1700s the Atsina people inhabited the Shaunavon area. They were called the "Gros Ventre of the Prairies".[25] They were called the "Gros Ventre of the Prairies".[25] Gros Ventre means “Big Belly" in French.[25] A'ani, A'aninin, and Haaninin are the Atsina tribe's autonyms.[26] These terms mean "White Clay People" or "Lime People."They shared many of the same beliefs as the Aboriginal tribes that would come later such as the Cree, Assiniboine, and Blackfoot tribes.[27][28]

The Gros Ventres were driven farther south by the Nehiyawak's (Plains Cree) and the Nakoda's (Assiniboine) aggression at the end of the eighteenth century.[29]

The Atsina signed Lame Bull's Treaty with the US government in 1855. They then settled on the Fort Belknap reservation in Montana in 1888.[28]

Food

The Cree, Assiniboine, and Blackfoot people primarily ate bison (buffalo). The meat was used and prepared in multiple ways. It was boiled, dried, and made into pemmican. The hide was used for robes and boots and the bones were used for tools.[30] They also ate other things like antelope, deer, elk, moose, gophers, and berries.[31] Sage was used often as a seasoning and bannock is a type of bread cooked over the fire.[32] The Indian Turnip was a common vegetable consumed by the Plains Aboriginals.[30] The Aboriginal women gathered the vegetables and berries and also prepared the meals.[30]

Hunting

The men of the southern plains hunted bison on foot before guns and horses arrived on the prairies.[32] They originally used spears but eventually this method was replaced bow and arrow which was lighter, therefore made hunting easier and more accessible.[30] They often used methods like the buffalo pound or buffalo jump to kill large herds.[32] However, the arrival of the fur trade brought on the decline and eventual extinction of the buffalo. The people began to hunt buffalo in the winter, a thing previously unpracticed,[30] in order to trade buffalo parts. By 1880, the once massive herds had been completely eradicated.[33]

The Horse

Originally the Plains people traveled on foot; however, this changed when horses arrived in Saskatchewan during the first half of the 1700s.[31] The horses carried much more than dogs could which made it easier to travel further and faster.[31] The Plains people used a travois which was a triangular frame of poles dragged by dogs. It was used to carry property.[32] When the horse arrived the Aboriginals placed the travois on the horses. The travois also provide the framework for the tipi, a good shelter that was easy to set up and take down.[32]

Spirituality

The plains Aboriginals believed all natural things such as Earth, animals, plants, trees, stones, sun, and clouds possessed a spirt. They believed in a Great Spirit or creator, and that humans existed within a connected web of life. .[30] Protection of the natural environment was a central piece in the Plains Aboriginal living. They believed humans must work with the earth, and its beings, for mutual survival.[34]

The medicine man (shaman) was a holy person who healed the sick, interpreted dreams, visions, and signs, and also led ceremonies. He was in closer contact than the rest of the population with the Great Spirit.[32]

Dream catchers, sweat lodges, pipes, smudging, and drumming were all relevant within the spirituality of the Plains aboriginals.[34]

Pow wows, ghost dances, and sun dances were also significant ceremonies.[30]

Treaties

Shaunavon lies within the Treaty 4 territory, also known as the Qu'Appelle Treaty. The treaty that includes most of southern Saskatchewan was signed on September 15, 1874 in Fort Qu'Appelle.[35] Bands that were not present in 1874 signed adhesion's in 1875, 1876, and 1877.

The treaties came at a time of intense Aboriginal starvation and suffering that followed decline of the buffalo population and the arrival of the white man.[34] The treaty was formed to control growing conflict between the Aboriginal people and the white settlers.

Lieutenant Governor Morris wrote to Ottawa in response to his concern over the unrest of the Aboriginal Peoples in the west.[34] In 1874 Morris received two letters. One said the Aboriginal Peoples in the Qu'Appelle region were willing to sign treaty, and the other gave government approval to establish the new treaty with the Cree, Saulteaux, and Assiniboine Plains Aboriginals.[27] The talks were dominated by the Hudson’s Bay Company’s perceived land ownership claims.

1913-1930

Prior to September 17, 1913

Shaunavon's earliest development as a civic center began in 1912 when the Canadian Pacific Railway bought the land as "a divisional point on its Weyburn-Lethnridge line"[36] going west to east. At the time there were 9 surrounding townships to the site. CPR would build tracks through the current site of the town mainly for its bountiful water supplies. As such, prior to the railroad being laid temporary shacks "sprung up around the Hipfner farm just north of the town site" of Shaunavon.[37] as people speculated as to where the railroad would go. The exact spot of where the railroad would go was unknown so many pre-incorporation buildings were built on skids along Government Road.[38]

Initial land sale and development

On the morning of Sept. 17, 1913 51 kilometers north in Gull Lake the sale of lots in the new CPR town site began. The Shaunavon Standard, established 1913, published its first issue the next day. It reported that "approximately 125 people"[39] were in attendance, and that many had been waiting for "13 days a 13 nights" for the sale to begin. In the same issue the Standard reported that "within eight hours 370 business and residential lots had been purchased".[36]

Early buyers spent $1,000,[39] present day costing $20,966 CND,[40] per residential position number, with some buyers buying multiple plots.[39] The name of the town remains a source of much debate.

From this initial purchase approximately 370 business and residential lots were bought[36] and by Nov. 27 1913 Shaunavon was incorporated as a village. Following the initial purchase of land Shaunavon witnessed incredible construction, within the first few months of its history Shaunavon expanded and came have several buildings addressing the needs of its people. These include: Brown-Naismith Hardware, the Kennedy Hotel (destroyed in 1918), Merchants Bank (now Royal Bank of Canada branch), the First Baptist Church and the Empress Hotel (renamed ‘The Shaunavon Hotel in 1915).[38] All but the Kennedy Hotel stills stand to this day. Also, in 1913 five grain elevators were built 1914 also saw continued growth in the village, with several more buildings popping up.

World War 1

Though World War I broke out in 1914 Shaunavon did not send a division until 1916, this is simply because Shaunavon, and Swift Current, did not have their own detachments until 1916. Early that year the battalion began recruiting and by April 27 the Shaunavon Standard reported that “124 officers and men” had joined and passed military inspection, while “nine more (had) signed up but have not yet passed.”[41] Members of the 209 reported to the Swift Current barracks on Sept. 15 1916. Many had been on leave helping their respective families on their farms.

Expansion

By 1916 Shaunavon had grown to 897 people,[42] keeping with its reputation as a boom town considering. Years after the war in 1922 Shaunavon appealed to the Employment Bureau to make Shaunavon a port of entry for American workers to help with harvest that year.[43] From its inception agriculture was a major component in the Shaunavon economy but 1922 saw a shortage in helping hands.

Early Mineral Development

Later that year lignite, a form of coal, was found south of Shaunavon and was soon after mined and heavily developed.[44] Lignite had always been present in the region and in some cases it was close enough to the surface that farmers could pick it up by hand and, for some time, had been using the lignite to heat their homes.[44]

Prior to great depression

The late twenties again saw a boom in development leading up to the great depression. In 1928 several new developments began in Shaunavon. In facts from April 24[45] to June 27, 1928[46] considerable funding went in to the town. In subsequent years several buildings were erected. 1928 saw the completion of the King’s Hotel.[38] In 1929 the Shaunavon Service Station was built,[38] later that year Crystal Bakery was built.[38]

Oil

In 1938, Shaunavon became the oil distribution centre for all plants within a 30-mile radius, as decided by the B.A. Oil Company.

In 1942[47] the Tide Water Associated Oil Company was interested in the region of southwest Saskatchewan for the development of oil. The discovery of oil in the region was in 1952[36][48][49] and the initial production came from Delta field, Dollard and Eastend.[47]

Dollard, approximately 13.4 km west of Shaunavon, was rated as one of the province’s best oil wells in September 1952. In November 1952, the company announced that two more wells would be drilled in this area.[50] With this discovery of oil, Shaunavon experienced a population boom and an increase in housing.[36] In March 1954 Tide Water’s 15th well was drilled in Dollard medium gravity oil field.[50]

The early 1950s was a great year for the oil industry in Southwest Saskatchewan.[47] In March 1953, Saskatchewan’s oil reserves were at 124,000,000 barrels, increasing from 21,000,000 from 1951.[51]

Industrial Park

In 1981, Shaunavon began developing 65 acres of serviced land for the Shaunavon Industrial Park.[52] The park is located on the west side of Highway #37.[53] This highway connects Shaunavon to the United States and the Trans- Canada north at Gull Lake. The extremities included electrical, natural gas and water services. The first park development was Foothills Pipelines (Sask.) Ltd.[54]

In 1983, land sold for $8,500- $9,500 an acre, marketed by SEDCO (Saskatchewan Economic Development Corporation).[54] In 2011, empty lots were created and ranged from $20,000- $50,000, depending on size. Oil-field based companies are the main parties interested in the industrial property.[53] Today the industrial park is home to a wind turbine that powers the Crescent Pont Wickenheiser Centre.[53]

Crescent Point Energy

Today, the oil industry continues to be a prominent part of Shaunavon.[48] Shaunavon’s unfolding development of oil, its history goes back to the discovery in 1952. After the initial discovery, five major and eight smaller fields were developed. A pipeline was completed in 1956, which carries the asphaltic base crude.[54] Seismographic crews were again present in the area in the early 1980s.[54] The construction of the Alaska Highway Gas Pipeline in 1981 from Burstall at the Alberta border reaches to Monachy at the US border. The pipeline passes 2 miles west of Shaunavon.[54]

Wave Energy drilled the first successful horizontal well,[55] however, a $665 million purchase in 2009,[56] made Crescent Point the predominant company.[57] Crescent Point Energy is an oil and gas company based out of Calgary, Alberta.[58] In 2009, Crescent Point Energy became the main oil company to invest in Shaunavon, owning approximately 90% of the oil play.[59]

Coal

Before the discovery of oil in 1952, Shaunavon relied on coal. Coal was dug outside Shaunavon in the hills and used to heat homes. Coal was used as barter during the Depression.[36] In 1932, the promise of Shaunavon Coal Company’s mine was rising. The Roe’s Coal Mine sold tunnel coal for $1.75 a ton and open mine coal for $1.50 a ton. In November 1942, the town feared a shortage of coal and in October 1945 there was a shortage of miners and high demand for coal.[50] Unfortunately, coal labour was cheap and miners were paid low wages.[49]

Today, Shaunavon is among one of the five operating coals mines in the entire province[60] and among one of three coal fields in Saskatchewan that contain almost five billion tonnes of Lignite resources. This means it is able to supply the province with thermal electric power for 300 years with the current rate of consumption.[61]

World War I/ World War II/ Korean War

In 1939, 83 men of the 14th Canadian Light Horse left for Dundurn[50] approximately 391 km northeast of Shaunavon. In May 1940, 65 men applied for active war service.[50] In total, from the town and area there were 600 men enlisted in World War I.[62] In October 1940 Shaunavon local, Dennis King with the C.A.S.F. England captured a German pilot after his plane was shot down.[50]

War efforts from Shaunavon were not just seen in battle because in the town war service drives began. June 1940, the Legion Ladies Auxiliary sent cigarette and blankets as gifts to local soldiers overseas and in 1943, the Shaunavon Services Committee sent parcels to 85 soldiers. Importantly, the Shaunavon Plaza Theatre gave a benefit performance to help boost the sale of War Saving Certificates and Stamps in July 1940.[50]

The town was able to financially contribute to the Second World War. This included $6,580 in 1941, $3,750 in 1942, and $10,000 in 1943 -1945.[50]

Cenotaph dedicated to soldiers stands proudly at Memorial Park in Shaunavon, Saskatchewan

Cenotaph dedicated to soldiers stands proudly at Memorial Park in Shaunavon, Saskatchewan

Today, Shaunavon’s local cenotaph still stands in Memorial Park, to commemorate the fallen soldiers of the World Wars. The cenotaph was built in 1925 and unveiled after completion in November 1926. It was built to commemorate those who fought in the First World War and a sealed list of men from the Shaunavon district is enclosed in the cenotaph. After the Second World War, the cenotaph then held a plaque of all those who were killed.[62][63][64][65][66][67][68]

Water

In May 1937, the town celebrated the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. The Royal Family was celebrated with flags decorating homes and shops. Citizens tuned into the radio to listen to the official broadcast of the coronation; it was a major event. The Royal Family was celebrated with flags decorating homes and shops. Citizens tuned into the radio to listen to the official broadcast of the coronation; it was a major event.[50] It was a big deal in 1939 when the Royal family visited Shaunavon. The royal train, with King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on board, stopped in the town and asked to be supplied with spring water. The infamous, “Oasis of the Prairies” water was given to the Royal family and nicknamed the Royal Water.[49][69][70]

Present Day

The two nearest reserves to Shaunavon are: the Nekaneet First Nation (Treaty 4) and wood Mountain First Nation (non-treaty). Nekaneet First Nation is 37.0149 km southeast of Maple Creek, SK, which is 134 km north west from Shaunavon. Wood Mountain First Nation is 4.82803 km southwest of Wood Mountain SK, 191 km away from Shaunavon.[71]

In 1913, settlers came to the area that would later be known as Shaunavon. Under a deal by the government at the time, land could be purchased throughout the province for as little as $10 a quarter section after building a homestead on the quarter. Within eight hours, 370 lots totaling $210,000 were purchased![6] While this brought settlers to the province, Shaunavon had an attraction that drew them to this region: water.

Water was essential for settlers and the water in the area was considered to be the purest and most plentiful. Within the course of one year, Shaunavon went from being a town of empty lots to a "Booming town" with a population of over 700 people. As a result, the town gained the nickname “Boomtown.” Shaunavon became the first community in Canada to grow from a village to a town in under one year.[6]

In 1914, the Canadian Pacific Railway brought the railroad through the community for the purpose of having access to the water supply for their locomotives. It was another positive sign for the community.

The royal visit by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth of the United Kingdom (and Canada) in 1939 brought fame to the community when the water that was used for the royal visit was supplied by the community. The town gained the title “The water capital of Canada.”[6]

The Skating Rink

Another important milestone in the community in the 1960s was the building of the public arena. With very little to do in the winter months, hockey was always a very important part of the community and an indoor facility was greatly needed. The centre included facilities for skating with artificial ice placed over the dirt ground. Later the extension for the curling rink was added to the existing facility and cement was added to the skating rink.

Rising insurance costs prompted the formation of Project 2002 – a plan to replace the rink with a more modern facility over the foundation of the old arena. With the new arena conforming to new building codes the price of insurance for the facility would be more affordable. Fundraisers such as the Canadian national women's hockey team visiting the Shaunavon Badgers and Hockey Day in Canada helped to raise funds for the new arena. Originally slated at $2 million, the price for the arena has grown to $6 million.

Railway

Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) is a shortline railway company located in southwest Saskatchewan, operating on former Canadian Pacific Railway tracks.[72] After the 1983 removal of the Crow Rate, a railway subsidy that benefitted farmers, farmers were forced to pay to ship their grain through larger mainline terminals.[73]

Adding to this, by favoring establishing grain terminals on their mainlines, the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Canadian National Railway deprived their thousands of miles of track across the Canadian prairies.[74] Railway companies were forced to abandon some lines in Saskatchewan.[75] These two developments decreased the amount of cars moving via railway and forced the Canadian Pacific Railway to abandon the Southwest Saskatchewan Railway portion of Great Western Railway.[74]

In January 2000,[74] the Canadian Pacific Rail contacted a company from Abbotsford, British Columbia, Westcan Rail,[76] to sell 550 km (330 miles) of track in southwest Saskatchewan.[77] Then in May, Westcan Rail began negotiations with CP Rail to purchase the four branch lines.[74] By June, there was an agreement and four subdivisions were formed. The line subdivisions include:

The Notukeu Subdivision, between Consul and Val Marie (100 miles);

The Altawan Subdivision, from Shaunavon and Consul (63 miles);

The Shaunavon Subdivision, from Limerick and Shaunavon (106 miles);

The Vanguard Subdivision, between Meyronne and Wymark (76 miles).[78]

The Great Western Railway is a fully owned Saskatchewan subsidiary of Westcan[79] and its headquarters are located in Shaunavon, Saskatchewan. Finally on September 13, 2000, Westcan Rail received provincial government approval to purchase the lines.[74]

In 2004, Westcan Rail wanted to sell the shortline.[80] In the fall of 2004, a group of local farmers and municipal governments formed a company and purchased the branch lines to keep the GWR running.[74] The private investors raised almost $4 million toward the $5.5-million purchase,[81] and the remaining $1.7 million was supplied by a provincial loan. Today it is still locally owned and operated.[82]

The GWR moves 6,400 cars annually. The initial goal in 2000, was 4,000 cars per year, which is the same as 30,000 fully loaded axle trucks off the roads.[82] It is the longest shortline in Saskatchewan.[83] Grain, fertilizer, corn, crude oil and recycled rubber are the main resources transported, as well as running a prosperous storage car business.[74] The GWR also owns 23 original grain elevators, and of these, the company still uses 16.[74]

The removal of the Crow Rate, which covered the cost of shipping grain, left farmers having to pay to ship their grains to world markets. It became more economical for grain producers to ship to large terminals along the main line. This brought about the closure and demolition of many wooden grain elevators along the line to Shaunavon. In the late 1990s, the CPR announced its intentions to sell the track leading to the southwest to WestCan Rail, a railway salvage operation. Action was swift. Grain Producers formed a coalition to lobby WestCan Rail. A deal was made that formed the Great Western Railway to run the line as a shortline with the eventual plans to purchase the railway back from WestCan Rail. Meanwhile, producers purchased the remaining standing wooden grain elevators in Shaunavon, Admiral, Eastend, Ponteix and Neville.

Today the Great Western Railway is owned by the coalition and continues to operate the shortline to southwest Saskatchewan. The Great Western Railway headquarters are located in Shaunavon.

Name origin

The name Shaunavon is believed to be a combination of the names of Lord Shaughnessy and William Cornelius Van Horne, two of the four founders of the Canadian Pacific Railway, although there is inconclusive evidence that suggests otherwise. The most damaging of this evidence is from Mr. F.G. Horsey, the CPR townsite representative in 1913, who said "he was personally in the Calgary office when a wire came through from Lord Shaughnessy declining the honour of having the town named after him, but suggesting that they name it Shaunavon after an area about his home in the old country . . .".[84] However, Shaughnessy was of Irish descent, but was born to dirt poor parents in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Thus, the existence of any kind of an old country estate is highly unlikely, and no such place shows up in Irish place name references. Since CP's files are silent on the subject, the derivation of the town name Shaunavon is likely to remain a mystery.[85]

Political history

Federal politics

Since Shaunavon was founded in 1913, the town and surrounding area have been represented by several different political parties and leaders. The town became a part of the new Maple Creek electoral district, established in 1914. In the 1917 federal election, Unionist party member and Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association organizer John Archibald Maharg ran unopposed, becoming the first Member of Parliament for the area.[86]

The next election in 1921 saw Progressive candidate and Gull Lake resident Neil Haman McTaggart win the district, and Liberal George Spence won in 1925. Spence would resign the next year, replaced with fellow Liberal William George Bock.[86]

Shaunavon had its first major political triumph in the 1930 election, when Shaunavon resident Dr. James Beck Swanston beat Bock and won the seat for the Conservatives. Swanston had run previously with the Conservatives, coming second in the two previous federal elections.[86] In addition to defeating Bock, Swanston also defeated another Shaunavon native: the Farmer Party candidate, Annie Hollis. One of Canada’s earliest female politicians, Hollis was the president of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association; the same organization John Archibald Maharg ran when he was elected. She later became the leader of the United Farmers of Canada.[87]

Swanston’s time in federal office ended in 1935, when Liberal candidate Charles Evans won the election. Swanston finished third in a race that was closely fought between four candidates. From 1935 until the ridings’ redistribution in 1952, the Maple Creek riding was in the hands of left-wing parties. The Liberals held the seat the entire time, except from 1945 to 1949, when Co-operative Commonwealth Federation candidate Duncan John McCuaig won.[86]

After 1953, Shaunavon became a part of the Swift Current—Maple Creek federal riding. The previous trend of voting for left-wing candidates changed in 1958, with the election of Jack McIntosh, who ran as a Progressive Conservative. McIntosh would represent the region until 1972, when fellow Progressive Conservative Frank Fletcher Hamilton was elected. Between 1958 and 1984, the Swift Current–Maple Creek seat in the House of Commons was property of the Progressive Conservatives.[88]

Swift Current–Maple Creek constituency combined with the Assiniboia constituency in 1987. Not long after, in 1993, Lee Morrison, a Reform candidate, broke the Progressive Conservatives' hold on the riding.[89] Morrison was elected again in 1997, when Shaunavon was represented by the newly formed Cypress Hills-Grasslands riding. The Canadian Alliance party and candidate David Anderson won handily in the 2000 federal election. Anderson, who became a part of the Conservatives in 2004, has represented Shaunavon federally ever since.[90]

Since Dr. Swanston's loss in 1935, the Member of Parliament representing Shaunavon has never been a native of the town: Figures like Morrison and Anderson, while representing the town federally, have come from other towns nearby (Morrison and Anderson come from Vidora and Frontier, respectively.)

Provincial politics

Provincially, Shaunavon was part of the Gull Lake constituency from the town's beginning in 1913 to 1917. They were led by Liberal party member Daniel Cameron Lochead. In 1917, Shaunavon became part of Saskatchewan's Cypress constituency, and elected Liberal leaders in three straight elections. Henry Halvorson won two of those elections, including the 1921 provincial election, in which he ran unopposed.[91]

Shaunavon had its own electoral district between 1934 and 1938, and elected Farmer-Labour candidate Clarence Stork. The Shaunavon district was abolished in 1938, and Shaunavon was made a part of the nearby Gull Lake constituency. The first leader of the new Gull Lake district was Liberal Harvey Harold McMahon, and he was replaced by CCF candidate Al Murray after the 1944 provincial election. The CCF would control the district until it was rezoned and renamed in 1952.[91]

Before 1952's provincial election, Shaunavon became the main headquarters for the Gull Lake constituency. The district was renamed after Shaunavon. In the new Shaunavon district, left-wing parties continued to rise, with the Liberals, CCF and, later, the New Democrats trading power over the area. In 1978, Shaunavon native Dwain Lingenfelter was elected to represent the area in the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan. Lingenfelter would go on to have a long political career, later seeing him become the head of Saskatchewan's NDP and a key member of Premier Roy Romanow's provincial cabinet.

1986's provincial election saw the streak of left-wing parties snapped by the Progressive Conservatives' Ted Gleim. The NDP won the seat back in 1991, as another Shaunavon local, Glen McPherson, was elected.[91]

In 1995, Shaunavon district was dissolved and redistributed into Wood River constituency and Cypress Hills constituency. McPherson, then the sitting MLA, changed parties from the NDP to the Liberals, and ran in Wood River. He won two elections in Wood River, and tied Saskatchewan Party opponent Yogi Huyghebaert in 1999. After a returning officer cast a deciding vote in favour of McPherson to break the tie, the result was thrown out and a by-election was called. McPherson chose not to run, and Huyghebaert was elected to legislative assembly.[91]

Shaunavon has been a part of the Cypress Hills constituency since 1995. The left-wing slant of the area, like most of Saskatchewan’s provincial politics, has seen a shift to the right. The election of the PCs’ Jack Goohsen in 1995 marked a new political beginning for the region. Goohsen resigned his seat in 1999 after being found guilty of soliciting sex from an underage prostitute.[92][93]

Cypress Hills is now represented in provincial legislature by Wayne Elhard, who won for the Saskatchewan Party in 1999 and is still the area's MLA.

Agriculture

Early Agriculture

Shaunavon is largely an agricultural community. Before settlement in 1913, Shaunavon was entirely open land. After settlement, the community largely subsisted on agriculture and ranching, including growing wheat that won top wards at international agriculture shows.[94]

The 1920s and 30s met with unprecedented economic boom. In 1921, Rancher Harry Otterson constructed the community’s first dipping vat. At the time, his land included 20,000 acres and 350 head of cattle.[95] In 1927, Otterson shipped a stock of cattle to Chicago for $16.65 per 100 lbs, which was the highest price for cattle post war up until that point.[96] Other animals bred in Shaunavon at the time included horses, pigs, and turkeys.[95]

From 1938 until 1969, the predominate crops where spring wheat, oats, barley, fall rye, and flax.[97] Like much of the rest of the Saskatchewan, the 1940s experienced difficult farming conditions. In June 1940, Shaunavon experienced an increasing number of grasshopper infestations that negatively affected crops.[98]

The 1940s also experienced several natural disasters. The winter of 1940 had record breaking snowfall. The snowfall disrupted several services, including road clearing and mail. During the winter, Rancher Dan Gunn spent several days travelling 10 miles to his neighbour’s farm in an unsuccessful trip to get some horse feed.[99]

In 1942, Shaunavon experienced two large prairie fires that destroyed thousands of acres of crops. The fires were believed to have been caused by sparks from machinery, with one spark originating in the Waldville district. The damage spread far enough to cause concern for citizens in Montana on the other side of the border.[100]

The 1940s also saw an incredible decline in crop yields, likely resulting from the conditions described above. In 1949, crop yields were at an all-time low. Spring wheat, barley, and fall rye produced a mere one bushel per acre. Oats proved completely impossible to grow, being recorded as producing zero bushels per acre.[97]

Agriculture in the 1950s

In 1950, cattle were still raised and continued to be exported to the United States. Joe White and Angus Willett where among those exporting, having exported 78 head of cattle to Low Moor, Iowa.[101] This time also saw a sharp turn upwards for agriculture. In 1948, residents of Shaunavon first began experimenting with fertilizer. The first farmer to use fertilizer was Anton Dynneson.[102] By 1950, the benefits for fertilizer had become evident, with Dynneson reporting better yields than years without fertilizer.[103] This year also marked a great emphasis on exporting crops, with Shaunavon containing a total of eight grain elevators.[94]

Agriculture and ranching continued to make their mark on the land and become a significant part of Shaunavon’s culture. In 1953, a lake northeast of Lake Athabasca was named Lake Maguire, in honour of Rancher Hugo Maguire.[104]

Modern Agriculture

The tail end of the 20th century marked a continual increase in crops. In 1970 durum wheat was first introduced. Canola was also introduced in this year, but was not replanted until the 1990s. This trend continued. In 1993, several new crops were introduced, including mustard, sunflowers, and peas.[97] 1993 was also noted for its large crop yields. This was especially true for oats, which peaked at 91.9 bushels per acre.[97] This was a stark contrast to the zero bushels per acre in 1949. Despite a slight dip in 2000, the crop yields have remained stable ever since.

As with many agricultural communities, several businesses have also sprung up in order to support the farms and ranches. One such business to open was Ranch House Meat Company. Created by Rancher Vince Stevenson, the business operates as a meat processing and deli store that also offers custom cuttings to local residents.[105]

Climate

| Climate data for Shaunavon | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.5 (58.1) |

19 (66) |

21.1 (70) |

31 (88) |

36 (97) |

39 (102) |

37.5 (99.5) |

38.5 (101.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

29 (84) |

21.5 (70.7) |

16 (61) |

39 (102) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−4 (25) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −11 (12) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

−3.9 (25) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −16.2 (2.8) |

−12.1 (10.2) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

4 (39) |

8.5 (47.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−9 (16) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −37.5 (−35.5) |

−38 (−36) |

−31.5 (−24.7) |

−20.5 (−4.9) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−3 (27) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−2.2 (28) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−25 (−13) |

−37 (−35) |

−42.2 (−44) |

−42.2 (−44) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18.8 (0.74) |

12.8 (0.504) |

23.3 (0.917) |

24.9 (0.98) |

57.2 (2.252) |

68.5 (2.697) |

52.4 (2.063) |

36.4 (1.433) |

31.1 (1.224) |

18.4 (0.724) |

16.9 (0.665) |

24 (0.94) |

384.6 (15.142) |

| Source: Environment Canada[106] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Population Characteristics

The town of Shaunavon rapidly grew in population during its first year. In January 1913, the area that would become Shaunavon had a population of zero;[107] by January of the following year, 750 people resided in the town.[50] The area surrounding Shaunavon consisted mostly of Anglo Saxon, Scandinavian, French Canadian, and Finnish homesteads.[108] The pioneers of Shaunavon were much the same, emigrating from all parts of Europe and the United States.[109] In 1916, Shaunavon experienced a minor drop in population,[110] before experiencing a steady growth in residence over the following 12 years.[107]

With the arrival of the Great Depression, the boomtown’s population decreased, from 1,896 residents in 1928, to a low of 1,571 residents in 1941.[50] But as the province recovered from difficult times, so did Shaunavon’s population.

Over the next 25 years, the population of Shaunavon increased steadily to an all-time high of 2,318 residents.[52] This was due to the discovery of oil in the region, which brought prosperity to the area.[52] From 1966 to 1977, the population hovered around the 2,300 mark.[111] After 1977, the population dropped steadily to 1,691 residents in 2006.[112] In 2007, the population began to climb again, to where it sits now at 1,756 residents.[112]

The current population of Shaunavon consists of 930 females and 825 males, with 83.4 per cent of the population over 15 years of age, and 46.8 years of age being the average age of the town’s residents.[112] Ninety-four per cent of Shaunavon’s residents identify English as their mother tongue, with the remaining six per cent identifying French, Cantonese, Dutch, Finnish, German, Ilocano, Korean, Mandarin, or Norwegian as their mother tongue.[112] The average household size in Shaunavon is 2.1 people, with the median household income at $38,759, and the unemployment rate at 2.9 per cent.[113]

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| January 1913 | 0[107] |

| October 1913 | 367[114] |

| January 1914 | 750[50] |

| July 1914 | 1,100[50] |

| 1916 | 897[110] |

| 1921 | 1,146[110] |

| April 1924 | 1,366[50] |

| 1926 | 1,491[107] |

| 1928 | 1,896[107] |

| 1931 | 1,761[115] |

| 1936 | 1,636[115] |

| 1941 | 1,571[50] |

| 1946 | 1,643[50] |

| 1951 | 1,625[52] |

| 1956 | 1,930[50] |

| 1961 | 2,128[50] |

| 1966 | 2,318[116] |

| 1967 | 2,309[111] |

| 1977 | 2,315[111] |

| 2001 | 1,775[116] |

| 2006 | 1,691[112] |

| 2007 | 1,775[48] |

| 2011 | 1,756[112] |

| Canada census – Shaunavon, Saskatchewan community profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2006 | ||

| Population: | 1,756 (3.8% from 2006) | 1,691 (-4.7% from 2001) | |

| Land area: | 5.10 km2 (1.97 sq mi) | 5.10 km2 (1.97 sq mi) | |

| Population density: | 344.2/km2 (891/sq mi) | 331.4/km2 (858/sq mi) | |

| Median age: | 46.8 (M: 45.2, F: 47.9) | 44.6 (M: 43.5, F: 45.3) | |

| Total private dwellings: | 877 | 871 | |

| Median household income: | $59,242 | ||

| References: 2011[117] 2006[118] | |||

Arts and culture

The Grand Coteau Heritage Centre is a museum and chapter library with a local art gallery and heritage exhibits on display. It was first formed in August 1931 by members of the Shaunavon Canadian Club. Derivation of the name of Shaunavon's Museum "Grand Coteau" comes from the title le grand coteau or grand slope, of the Missouri as applied by the explorer La Verendrye.[119]

The Grand Coteau has received numerous donations over the years. The museum only displays a small fraction of the estimated 11,000 artifacts collected. The museum houses a heritage room in the basement, an art gallery, and a taxidermy wildlife exhibit.[120] For a number of years after World War II, the museum was severely short staffed. Frank O. Bransted, a Shaunavon resident, was the sole volunteer at the Grand Coteau. In 1957, the Grand Coteau was bought by the Town of Shaunavon from the school board for the sum of $1.00. It was then moved to its current location on Shaunavon’s Centre Street.[120]

The Plaza Theatre on main street runs both movies and theatrical shows.

The Darkhorse Theatre performs two major productions a year, and is well known for producing quality shows. The Darkhorse Theatre uses top of the line production equipment to compliment the set design, wardrobe, and makeup for the major productions. The spring production consists of three pub night performances and the fall production offers six nights of dinner theatre.[6]

Attractions

Tourism

Tourists will find several attractions in Shaunavon and some in the area. Shaunavon's tourist attractions include the Darkhorse Theatre, the Grand Coteau Heritage & Cultural Centre, the Plaza Theatre, Rock Creek Golf Course, and the Crescent Point Wickenheiser Centre. A skateboarding area complete with rails, ramps, and several quarter pipes can be found in Jubilee Park.[121] Multiple baseball diamonds sit on the grounds of the Crescent Point Wickenheiser Centre. A swimming pool opens and cools off locals during the summer months. Two tennis courts are available to the public.[122]

Annual events such as the Boomtown Days Rodeo are held every July. The first rodeo was held in 1914, one year after the town was founded. The inaugural Boomtown Days Rodeo was held on July 1, 1914.[123] The Shaunavon & District Music Festival is an annual event held in February or early March. The first Shaunavon & District Music Festival was held on April 15, 1928.[124]

Shaunavon's Centre Street contains many local businesses for shopping needs.

Shaunavon & District Music Festival

First started in 1928, the festival has been a staple in Shaunavon for 83 years. The inaugural festival took place on April 15, 1928. When it was first started, the Saskatchewan Music Festival Association was then known as the Southwestern Branch of the Saskatchewan Musical Association.[124] There was years where the festival did not take place due to World War II. The festival is organized by the Saskatchewan Arts Council and Saskatchewan Music Festival Association. The festival also provides scholarships for music education students. There were nearly $3500 in scholarships handed out at the 2014 festival.[125] The festival annually chooses an honorary patron of the festival. The chosen patron is routinely a well-known citizen of Shaunavon. Occasionally a citizen of the neighbouring towns of Eastend, Gull Lake, or Maple Creek will be chosen as the honorary patron.[125]

Other Attractions

The Pine Cree Regional Park is located approximately 30 km from Shaunavon. There are 29 campsites located along the creek. The park features amenities such as barbecues, playgrounds, ball diamonds, and bridges. The Pine Cree Regional Park is truly a rustic get-a-way, as the entire park is non-electrical.

Showarama occurs in the spring showcasing merchants in and around the community, I love Shaunavon Day and the Parade of Lights take place each winter, and Boomtown Days and the Pro-Rodeo occur during the summer. The Shaunavon Rodeo Grounds serve as the backdrop for the annual Shaunavon Pro Rodeo. The Shaunavon Rodeo Association has hosted events, both amateur and professional, for over 40 years. The Shaunavon Pro Rodeo is a CPRA sanctioned event and features many professional competitors that follow the rodeo circuit east from the Calgary Stampede. The Rodeo Grounds are located about 6 km west of Shaunavon on Highway #13.[6]

Regional Attractions

- Big Muddy Badlands, a series of badlands in southern Saskatchewan and northern Montana along Big Muddy Creek.[126]

- Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park, an interprovincial park straddling the southern Alberta-Saskatchewan border, located north-west of Robsart. It is Canada's first and only interprovincial park.

- Cypress Hills Vineyard & Winery, open by appointment only from Christmas until May 14.[127]

- Fort Walsh, is part of the Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park. As a National Historic Site of Canada the area possesses National Historical Significance. It was established as a North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) fort after and at the location of the Cypress Hills Massacre.

- Grasslands National Park, represents the Prairie Grasslands natural region, protecting one of the nation's few remaining areas of undisturbed dry mixed-grass/shortgrass prairie grassland.

- The Great Sandhills, is a sand dune rising 50 feet (15 m) above the ground and covering 1,900 square kilometers.[128]

- Robsart Art Works, opens July 1 to August 28, 2010 from 1 to 4 p.m. and by appointment and features Saskatchewan artists featuring photographers of old buildings and towns throughout Saskatchewan.[129]

- T.rex Discovery Centre, a world class facility to house the fossil record of the Eastend area started many years before the discovery of "Scotty" the T.Rex in 1994.[130]

Sports

Shaunavon has many seasonal and year-round venues that help to boost tourism and entertain residents. It also has numerous organizations offering sport, culture, recreational and social opportunities including hockey, soccer, curling, figure skating, karate, fastball and baseball, volleyball, basketball, performing arts, and a variety of dance disciplines.

The service groups include: Shaunavon Kinsmen & Kinettes, Shaunavon Legion & Legion Auxiliary, Shaunavon Elks & Royal Purple, Shawnees, Knights of Columbus, Hometown Club, Senior Citizens and a number of church organizations.

Recreational facilities include: a bowling alley, walking trails, Recreation Complex, tennis courts, horseshoe pits, swimming pool, regional library, playgrounds, fitness gym, golf club, rinks, movie theatre, ball park, skating and curling.[6]

During the summer months, the skating rink serves as a community centre for various events and in the fall and winter is covered with ice again for both skating and curling.

In the summer months an outdoor recreation swimming pool is available and a 9-hole golf course is also open. Camping is available at the Shawnee Campground adjacent to Memorial Park in the heart of the town.

Shaunavon is home to the Shaunavon Badgers of the Southwest Saskatchewan Hockey League.

Shaunavon hosted CBC's Fifth Annual Hockey Day in Canada on February 21, 2004.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Saskatchewan Highways 13 and 37 connect to Shaunavon.

Shaunavon is served by the Shaunavon Airport. Shaunavon's airport has a regulation asphalt, lighted runway, 3,000 feet (910 m) in length. The airport has LWIS weather system as well as a global positioning system to assist pilots to their destinations.[6]

A Courtesy Car is operated by volunteers Monday to Friday between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m.

Services

Government Services

Shaunavon is the main large centre next to Swift Current in southwestern Saskatchewan meaning that the town has a lot of government services.[131]

The town houses a local RCMP detachment. Their phone number is 306-297-5550.[132] Also in Shaunavon is a Service

Canada facility, the Shaunavon Scheduled Outreach Site. It helps residents with services such as pension information, labour standards, disability benefits, veterans affairs, job search assistance, amongst over services.[133]

Shaunavon Hospital and Care Centre is part of the Cypress Health Region. The hospital offers a full array of services including acute care, emergency services, lab and x-ray services, home care, along with many other services. It also offers primary health care services with physicians and nurse practitioners.[134] The Shaunavon Branch of Regional Library is located at the Grand Coteau Heritage and Cultural Centre.[135]

Shaunavon is home to three different schools, two elementary schools and one high school. Under the Chinook School Division is Shaunavon Public School, which is the town’s public elementary school, and Shaunavon High School, which is the town’s only high school.[136] Shaunavon also has one of the few rural Catholic schools in Saskatchewan, Christ the King School, an elementary school.[137]

Stores

Shuanavon is home to a variety of stores, from grocery to clothing stores.[138]

The Shaunavon Co-op has been part of the town since 1935. It offers such services such as a food store, home and agro centre, gas bar and cardlock.[138]

Other stores located in Shaunavon are Legacy Computers/The Source, Walter’s Home Furnishings, JoZ CLoZ, TS&M, Browzer’s Florist and Gift Shop, Andersboda, Shaunavon Foods, Sask. Liquor Store, Jae’s Pharmacy Ltd., Shaunavon Rexall Drug Store, and TB!S – The Bargain Shop.[139]

Restaurants

Shaunavon has a variety of good restaurants. Harvest Eatery and Fresh Market located on Centre Street, is a gourmet restaurant that uses all local ingredients.[140] Overtime Restaurant and Sports Lounge offers a variety of menu items.[141]

Banks

Shaunavon has three different banks. The two major national banks are the Royal Bank and CIBC.[139] Shaunavon is also home to the Shaunavon Credit Union, which has been part of the town since 1944. On January 1, 2015 Shaunavon Credit Union will merge with Affinity Credit Union to become a branch of them and access more services.[142]

Businesses

Shaunavon's businesses include everything from dealerships to radio stations

- The Shaunavon Plaza Theatre is shown all lit up for an evening showing at its location on Centre Street in Shaunavon, SK.

Locally owned is the Shaunavon Plaza Theatre, which is the movie theatre in town located on Centre Street.[143] Shaunavon also has two radio stations CJSN 1490, and Eagle 94.1[144] and the local newspaper The Shaunavon Standard.[145]

Shaunavon is also home to two dealerships, Silver Sage Chev and Shaunavon Industries (1980) Ltd. Silver Sage Chev is a General Motors car dealership.[146] Shaunavon Industries (1980) Ltd. is a John Deere machinery dealership.[147]

Recreation Facilities

Shaunavon has a wide range of recreation facilities for residents to use.

During the winter there is the Crescent Point Wickenheiser Centre, which houses a skating rink, four sheets of curling ice and the Hayley Wickenheiser Museum. There is also an outdoor skating rink in Shuanavon.[131]

During the summer Shaunavon has a heated outdoor swimming pool, tennis courts and a skate board park, all located adjacent to each other. Shaunavon is also home to the Rock Creek Golf Course, a nine-hole grass green course.[131]

Hotels

Shaunavon is home to a number of hotels including the Canalta, Bears Den Lodge, King’s Hotel, Hidden Hilton Hotel, and Stardust Motel.[145]

The Canalta is located on First Avenue. It offers many amenities such as air conditioning, free high-speed internet, kitchenettes available, hot tub, refrigerators, fitness centre, amongst many other amenities.[148]

Education

- Shaunavon High School (grades 8 - 12)

- Shaunavon Public School (grades K - 7)

- Christ the King School (grades K - 7)

- Cypress Hills College

Media

- Southwest Boomtown Bargain Finder

- Shaunavon Standard

Radio

- CJSN 1490 Radio - Shaunavon has a 1000 Watt station that simucasts CKSW radio, with local inserts and a half-hour of local programming daily.

Famous residents

Hayley Wickenheiser

Hayley Wickenheiser is a five time Olympic medalist and is a member of the Canadian National Women's hockey team.[149] She was born in Shaunavon in 1978.[149] She was first selected to the Women's Olympic team when she was 15 years old.[150] She was elected to the International Olympic Committee[150] and was appointed to the Order of Canada.[150] She became the first female hockey player to notch a point in a men's professional game while playing for the Kirkkonummen Salamat.[150] She was inducted into the Canadian Walk of Fame in 2014.[151]

Braydon Coburn

Braydon Coburn is a NHL defensemen currently playing for the Tampa Bay Lightning.[152] He played his Junior Hockey for the WHL's Portland Winter Hawks[153] and was the recipient of the WHL's Humanitarian Award in 2003-04.[154] He leads an annual hockey school in Shaunavon and the school is open to boys and girls.[155]

Rhett Warrener

Rhett Warrener was born in Shaunavon in 1976.[156] He was a second round selection by the Florida Panthers in the 1994 NHL entry Draft.[156] He has played for the Florida Panthers, Buffalo Sabres and the Calgary Flames.[156] He retired from hockey in 2009 and became a scout for the Calgary Flames.[157]

Frances Hyland

Frances Hyland was an actor and director who was born in Shaunavon in 1927.[158] She was involved in radio dramas, film and television work.[159] She studied Arts at the University of Saskatchewan before entering the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, England.[158] She made her London debut as Stella in A Streetcar Named Desire.[158] She made frequent appearances on television including The Great Detective on CBC.[158] She had a role on CBC-TV's show Road to Avonlea where she played Sara Stanley's nanny Louisa J. Banks.[160] Her awards include being named to the Order of Canada, lifetime achievement awards from the Governor General and the Toronto arts community, and ACTRA's John Dranie award for distinguished contribution to broadcasting.[159] She died in 2004.[159]

Dwain Lingenfelter

Dwain Lingenfelter was born in Shaunavon in 1949.[161] He was voted MLA of the constituency of Shaunavon from 1978 to 1986.[161] He was a cabinet minister for former Saskatchewan Premier Roy Romanow and in 1995 he became Deputy Premier and was appointed Minister of the Crown Investments Corporation in 1997.[161] He was appointed the Minister of Agriculture and Food in 1999 but resigned in 2000.[161] He moved to Calgary as vice-president of government relations for Nexen, an international oil and gas company.[161] He returned to politics and won the NDP provincial leadership in 2009 but resigned in 2011.[162]

Ann Eriksson

Ann Eriksson was born in Shaunavon in 1956.[163] She is an author who has published 4 novels including Decomposing Maggie, In the Hands of Anubis, Falling from Grace and High Clear Bell of Morning that was released in 2014.[163] He holds a biology degree from the University of Victoria.[163] She is a member of the Writers Union of Canada.[163] She is the founding director of the Thetis Island Nature Conservancy.[163]

Everett Baker

Everett Baker was born in Minnesota and immigrated to Canada in 1916.[164] He settled in Aneroid, Saskatchewan, and took up farming there.[164] He and his wife, Ruth, lived in Shaunavon from 1945 until his death in 1981.[165] In the late 1930s he began to take his photos.[164] During his 21 years as a field man for the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, he captured most of his images.[165] He left 10,000 slides—now the property of the Saskatchewan History and Folklore Society.[164] He became its first president in 1957.[164]

Mayors and Revees

Mayors

The Shaunavon Standard documented many accomplishments by town council, highlighted by the purchasing of fire equipment in the early years, the construction and maintenance of roads and sidewalks, and the focus on emergencies services and recreational initiatives throughout their history.[50]

| Era[166] | Mayor[166] | Terms[166] | History |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1913-1929 | R. Roycroft, Overseer | 1913-14 | Shaunavon held its first council meeting December 22, 1913. Robert Roycroft was the overseer. Percy Woods and James McConbrey were also voted in.[50][166]

In 1914, Shaunavon had a population of 1,100, which elevated them status of a town.[50] |

| George Barr | 1915 | Geo. Barr was elected first mayor in 1915.[167] | |

| T.J.E. Campbell | 1916, 1923-26 | In May, 1916, T.J.E. Campbell was elected mayor of Shaunavon by acclamation. In December, Campbell resigned after enlisting in the 209th Battalion. In response, H. Brown and George Jackson were elected by acclamation.[50]

T.J.E. Campbell survived his time at war and died in February, 1952.[168] A valued citizen, Campbell was remembered for his betterment of the town. Campbell served six terms as mayor: 1916, 1923 to 1926, and into 1930.[50] | |

| A. A. Hassard | 1917 | A.A. Hassard was mayor of Shaunavon, 1917. In December, J.E. Mitchell and P.L. Naismith were nominated for head set.[50] | |

| P.L. Naismith | 1918 | Naismith defeated Mitchell to become mayor in 1918.[50] | |

| J.E. Mitchell | 1919-22, 1927-29 | J.E. Mitchell served four straight terms as mayor, each time being elected by acclamation.[50]

In October 1922, Mitchell announced he would not run the following year. This led to concern over lack of candidates for the civic election in December. George Barr and T.J.E. Campbell were the two candidates running for the office of mayor, with Campbell winning to serve two more consecutive terms.[50] Mitchell was back as mayor in 1927 to 1929, and presided during the opening of Shaunavon's new Court House.[169] | |

| 1930-1959 | T.J.E. Campbell | 1930 | T.J.E. Campbell survived his time at war and died in February, 1952. A valued citizen, Campbell was remembered for his betterment of the town. Campbell served six terms as mayor: 1916, 1923 to 1926, and into 1930.[50] |

| C. Jensen | 1931-34, 1952-58 | Chris Jensen was acclaimed for the mayor’s chair in February 1930, after Campbell resigned.[170]

A town council meeting in February 1932 was postponed so councillors could watch the Swift Current versus Shaunavon hockey game.[50] In October 1952, Jensen was once again elected by acclamation for mayor’s chair, and continued for seven more terms. Shaunavon’s population was listed as just over 2,200 people.[50] Jensen resigned after 17 years of civic service. He served for five years as councillor and 12 as mayor. In May, Syd Stevens defeated Max Houston for mayor’s chair.[50] | |

| Jas Cardno | 1935-39, 1941-43 | In November 1934, Jas Cardno became new mayor by acclamation.

In 1936, Cardno defeated Chris Jensen for the chair, won mayor’s chair over Robert McIntyre (by a substantial majority), in 1938. But in 1940, Cardno was once again elected to mayor by acclamation.[50] Cardno announced the town’s finances were in trouble, in 1935.[50] In 1941, Shaunavon had a population over 1,500. The town paid councillors $2.50 per meeting and mayor $4.00.[50] In June 1943, Cardno resigned from his position after seven years of mayoral service. And in July, R.L. Fisher was elected by acclamation.[166] | |

| J.C. Hossie | 1940 | December 1940, Mayor J.C. Hossie declared Boxing Day a civic holiday.[50] | |

| R.L. Fisher - part, W. Killburn - balance | 1944 | In May 1944, Mayor Robert Lewis Fisher died at the age of 54. W. Killburn balanced out the duties.[166] | |

| Neil McLean | 1945-46, 1949-51 | In November 1945, Neil McLean was elected as mayor by acclamation, and served for five terms throughout his career.[50] | |

| G.L. Humphries | 1947-48 | Town Council, under the direction of G.L. Humphreys in 1948, moved to establish an airfield owned by the municipality.[50] | |

| Syd Stevens | 1959 | After a town council meeting in June, 1959, Shaunavon adopted Daylight Saving Time.[50] | |

| 1960–present | Syd Stevens | 1960-61 | |

| Albert Leia | 1962-63 | In November 1962, Albert Leia was elected mayor, defeating Norman Ross.[166] | |

| David Hanna | 1964-65 | In 1964, David Hanna defeated incumbent Leia for mayor’s chair. Hanna was the youngest mayor to serve Shaunavon.[50] | |

| Robert Nelson | 1966-79 | In November 1966, G.E. Boyd was elected mayor but resigned in March 1967. Bob Nelson and Syd Stevens ran as candidates and the following year, Nelson defeated Stevens by 79 votes for mayor’s chair.[50]

Nelson was re-elected in October 1978, for what would turn out to be his final term. He defeated Bruce Pearson, 495 votes to 350 votes.[50] Nelson served a total 14 consecutive years.[166] | |

| Bruce Pearson | 1980-87 | Bruce Pearson defeated long-time incumbent, Robert Nelson, for mayor’s chair in 1980 and again in 1982.[50]

In August 1986, town council stated they could not pay the bills for the town’s old train station.[50] Smoking was banned from town council meetings in January, 1987.[50] In September 1988, Pearson stepped down from municipal politics after serving 15 years. Pearson was alderman for seven years and mayor for eight.[166] | |

| Norm Lavoy | 1988-94 | Norm Lavoy was selected as the new mayor in October, 1988.

In August 1994, Lavoy stepped down after six years in the head chair. He had also served six years prior as an alderman.[50] | |

| Gordon Speirs | 1994-96 | Gordon Speirs was elected as mayor by acclamation in October, 1994. He previously served eight years on council. Speirs also served as Fire Chief for over 40 years and remained involved in the community his whole life.[50] | |

| Ron Froshaug | 1997-99 | In 1997, former alderman Ron Froshaug became mayor.[50] | |

| Sharon Dickie | 2000–present | In October 2000, Sharon Dickie was elected mayor. Dickie made history by being the first female mayor.[50]

A month-long strike by the town’s employees ended in August 2006, after a contract was reached with the town of Shaunavon.[50] In 2009, Dickie returned for her fourth consecutive term as mayor. She defeated Pete Allen 380 votes to 226 votes.[50] In September 2012, urban municipalities’ term of office increased from three to four years. Dickie remains mayor to date.[170] | |

Reeves

Shaunavon resides in the rural municipality of Grassy Creel (No. 78).[171] In 1913, the first reeve was L.T. Bergh. In 1956, they introduced two year terms and in 2012, four year terms. Kerry Kronberg currently sits as reeve.[172]

See also

References

- ↑ "2011 Community Profiles". Statistics Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- ↑ National Archives, Archivia Net, Post Offices and Postmasters

- ↑ Government of Saskatchewan, MRD Home. "Municipal Directory System". Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- ↑ Canadian Textiles Institute. (2005), CTI Determine your provincial constituency

- ↑ Commissioner of Canada Elections, Chief Electoral Officer of Canada (2005), Elections Canada On-line

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 http://www.saskbiz.ca/communityprofiles/CommunityProfile.Asp?CommunityID=330

- ↑ Daschuk, James (1961). Clearing the Plains. Regina: University of Regina. p. 4.

- ↑ Daschuk, James (1961). Clearing the Plains. Regina: University of Regina. p. 11.

- ↑ Daschuk, James (1961). Clearing the Plains. Regina: University of Regina. p. 16.

- ↑ Daschuk, James (1961). Clearing the Plains. Regina: University of Regina. p. 183.

- ↑ Ganley, J (1955). Geography and Early Settlement. Shaunavon, SK: Shaunavon town and community. p. 19.

- 1 2 Anderson, Alan (2006). "French Settlements". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.

- ↑ Archer, John. Saskatchewan A History. Regina: Western Producer Prairie Books. p. 140.

- ↑ "Shaunavon Jubilee Edition". Shaunavon Standard.

- ↑ Ganley, J (1955). Geography and Early Settlement. Shaunavon, SK: Shaunavon town and community. pp. 20–1.

- ↑ Anderson, Alan (2006). "French and Métis settlements". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.

- ↑ MacLean, Roger. "Census of the three provisional districts of the North-West Territories, 1884-5". Early Canadiana Online.

- ↑ Baker, Everett; Fedyk, Mike; Mitchell, Ken; Poirier, Thelma; Porter, Brian; Wilson, Audrey; Wilson, Garrett (2010). Fort Walsh to Wood Mountain - The North-West Mounted Police Trail. Benchmark Press.

- ↑ Winkel, James (2006). "Red River Cart". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.

- 1 2 Black, Norman (1913). History of Saskatchewan & the North-West Territories. Regina Saskatchewan Historical Co.

- ↑ History of Métis in Southwest Saskatchewan - Exhibition. Swift Current Museum.

- ↑ "Father Decorby". St. Lazare.

- ↑ Lapointe, Richard; Tessier, Lucille (1988). The Francophones of Saskatchewan - a history. Regina: Campion College.

- ↑ St-Onge, Nicole; Podruchny, Carolyn; Macdougall, Brenda (2012). Contours of a people. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- 1 2 3 "Gros Ventres". Encyclopedia of the Prairies. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- 1 2 Daschuk, James (1961). Clearing the Plains. Regina: University of Regina.

- 1 2 "Atsina". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ "Atsina Indians". Lewis & Clark. National Geographic.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Plains People". Canada's First Peoples.

- 1 2 3 "Aboriginal People: Plains". Historica Canada.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Saskatchewan History: The First Peoples".

- ↑ "Palaeoindian". Historica Canada.

- 1 2 3 4 Stonechild, Blair (2006). "Aboriginal Peoples of Saskatchewan". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.

- ↑ "The Treaties". Canada's First Peoples.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McLennan, David (2008). Our Towns: Saskatchewan Communities from Abbey to Zenon Park Regina. Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina Press. pp. 360–2. ISBN 0889772096.

- ↑ "Shaunavon Town and Community Dedicated to A Proud Past and Bright Future: Saskatchewan Golden Jubilee 1905-1955".

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Heritage Walking Tour - Grand Coteau".

- 1 2 3 Shaunavon's 19th Birthday – anniversary September 17. The Shaunavon Standard. September 22, 1932

- ↑ http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/

- ↑ New Men Enlisted”. The Shaunavon Standard. April 27, 1916.

- ↑ The Canada Year Book 1916-1917 Statistics Canada.

- ↑ “Shaunavon is port of entry for laborers”. The Moring Leader. September 13, 1922.

- 1 2 Lignite operation started south of Shaunavon. The Moring Leader. November 25, 1922.

- ↑ “$80,000 in building going up”. The Moring Leader. April 24, 1928.

- ↑ “$250,000 in building going up”. The Moring Leader. June 27, 1928.

- 1 2 3 Marsh, Arden & Hill, Peter. Saskatchewan Geological Survey & Saskatchewan Ministry Of The Economy. Off the Beaten Track: Oil Shows in the Upper Shaunavon Member, West of the Main Oil Field Trend, Southwestern Saskatchewan (n.d.). Geoconvention. Saskatchewan Ministry of the Economy, 2014. Web.

- 1 2 3 McLennan, David (2006). "Shaunavon". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.

- 1 2 3 "History." Town of Shaunavon. Town of Shaunavon, n.d. Web. 10 Oct. 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 "Shaunavon 1913-2013: 100 Years of History". The Shaunavon Standard. September 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Loomis Discovery Fifth This Year in Saskatchewan." The Globe and Mail [Toronto] 6 Mar. 1953: 20. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 McLennan, David (2008). Our Towns: Saskatchewan Communities from Abbey to Zenon Park Regina. Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina Press. p. 361. ISBN 0889772096.

- ↑ Park, Gary. Lower Shaunavon Seen as a Key Base for Years Petroleum News. Retrieved 2014-11-9.

- ↑ Crescent Point pays $665M for Wave Energy Toronto Star. 24 Aug 2009. Retrieved 2014-11-10.

- ↑ "Crescent Point Consolidates Position in Lower Shaunavon Oil Resource Play with Strategic Acquisition of Wave Energy." 24 Aug 2009. Toronto. Retrieved 2014-11-1.

- ↑ Crescent Point Contact Information Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ Stonehouse, Darrell. Activity Heating up in Southwest Saskatchewan. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ Parchewski, Julie L. "Coal." The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina, 2006. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ "Coal: Powering the Province." ORE Magazine (2013): 1-35. Saskatchewan Mining Association, 2013. Web. 25 Oct. 2014.

- 1 2 "Cenotaph Needs Repair." The Shaunavon Standard, 07 Feb. 2012. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ "Shaunavon and Two World Wars." Shaunavon: Town and Community. Shaunavon, Sask.: S.n., 1955. 32. Print.

- ↑ "Heritage Walking Tour." Town of Shaunavon. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ Robinson, Ashley. Memorial Park Cenotaph. 2014. Shaunavon.

- ↑ Centennial Activity Book: Shaunavon Photo Scavenger Hunt. Shaunavon: Town of Shaunavon, n.d. Print.

- ↑ Heritage Room. Shaunavon: Grand Couteau Heritage & Cultural Centre, n.d. Print.

- ↑ Shaunavon Centennial Quilt 1913-2013. Shaunavon: Canadian Heritage, 2013. Print.

- ↑ Town of Shaunavon. Welcome Shaunavon. Shaunavon: Town of Shaunavon, n.d. Print.

- ↑ "Shaunavon." Saskbiz.ca. Saskbiz, n.d. Web. 29 Sept. 2014.

- ↑ "First Nations Map Of Saskatchewan". Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. Government of Canada.

- ↑ Great Western Railway. The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- ↑ Grain Transportation Policy and Transformation Retrieved 2014-11-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Great Western Railway Website Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ↑ Truck Transportation The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- ↑ Schmidt, Lisa. "B.C. firms buy four Sask. rail lines" Leader Post. 6 June 2000. Print.

- ↑ "CPR. Westcan Close Sale of Four Branchlines in Southwest Saskatchewan. Press Release. 8 Sept 2014. Print.

- ↑ "Great Western Railway getting on track" Leader Post. 9 Aug 2000. Print.

- ↑ Lilley, David. "New life for southwest branch lines" Advance Times. 3 July 2000. Print.

- ↑ Ewins, Adrian. Farmers Reluctant to Buy Rail Line Western Producer. 11 March 2004. Retrieved 2014-11-1

- ↑ Pruden, Jana. "Rural Residents Hope to Keep Railway Alive" Star Phoenix. 13 Dec 2004. Print.

- 1 2 Great Western Railway Keeps Grain on Rails Government of Saskatchewan. News Release. 13 Dec 2004.