Amber

| Part of a series on |

| Paleontology |

|---|

|

|

Organs and processes |

|

History of paleontology |

|

Branches of paleontology |

|

Paleontology Portal Category |

Amber is fossilized tree resin (not sap), which has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times.[2] Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects.[3] Amber is used as an ingredient in perfumes, as a healing agent in folk medicine, and as jewelry.

There are five classes of amber, defined on the basis of their chemical constituents. Because it originates as a soft, sticky tree resin, amber sometimes contains animal and plant material as inclusions. Amber occurring in coal seams is also called resinite, and the term ambrite is applied to that found specifically within New Zealand coal seams.[4]

History and names

The English word amber derives from Arabic ʿanbar عنبر[5] (cognate with Middle Persian ambar[6]) via Middle Latin ambar and Middle French ambre. The word was adopted in Middle English in the 14th century as referring to what is now known as ambergris (ambre gris or "grey amber"), a solid waxy substance derived from the sperm whale. In the Romance languages, the sense of the word had come to be extended to Baltic amber (fossil resin) from as early as the late 13th century. At first called white or yellow amber (ambre jaune), this meaning was adopted in English by the early 15th century. As the use of ambergris waned, this became the main sense of the word.[5]

The two substances ("yellow amber" and "grey amber") conceivably became associated or confused because they both were found washed up on beaches. Ambergris is less dense than water and floats, whereas amber is too dense to float, though less dense than stone.[7]

The classical names for amber, Latin electrum and Ancient Greek ἤλεκτρον (ēlektron), are connected to a term ἠλέκτωρ (ēlektōr) meaning "beaming Sun".[8][9] According to myth, when Phaëton son of Helios (the Sun) was killed, his mourning sisters became poplar trees, and their tears became elektron, amber.[10]

Amber is discussed by Theophrastus in the 4th century BC, and again by Pytheas (c. 330 BC) whose work "On the Ocean" is lost, but was referenced by Pliny the Elder, according to whose The Natural History (in what is also the earliest known mention of the name Germania):[11]

Pytheas says that the Gutones, a people of Germany, inhabit the shores of an estuary of the Ocean called Mentonomon, their territory extending a distance of six thousand stadia; that, at one day's sail from this territory, is the Isle of Abalus, upon the shores of which, amber is thrown up by the waves in spring, it being an excretion of the sea in a concrete form; as, also, that the inhabitants use this amber by way of fuel, and sell it to their neighbors, the Teutones.

Earlier[12] Pliny says that a large island of three days' sail from the Scythian coast called Balcia by Xenophon of Lampsacus, author of a fanciful travel book in Greek, is called Basilia by Pytheas. It is generally understood to be the same as Abalus. Based on the amber, the island could have been Heligoland, Zealand, the shores of Bay of Gdansk, the Sambia Peninsula or the Curonian Lagoon, which were historically the richest sources of amber in northern Europe. It is assumed that there were well-established trade routes for amber connecting the Baltic with the Mediterranean (known as the "Amber Road"). Pliny states explicitly that the Germans export amber to Pannonia, from where it was traded further abroad by the Veneti. The ancient Italic peoples of southern Italy were working amber, the most important examples are on display at the National Archaeological Museum of Siritide to Matera. Amber used in antiquity as at Mycenae and in the prehistory of the Mediterranean comes from deposits of Sicily.

Pliny also cites the opinion of Nicias, according to whom amber "is a liquid produced by the rays of the sun; and that these rays, at the moment of the sun's setting, striking with the greatest force upon the surface of the soil, leave upon it an unctuous sweat, which is carried off by the tides of the Ocean, and thrown up upon the shores of Germany." Besides the fanciful explanations according to which amber is "produced by the Sun", Pliny cites opinions that are well aware of its origin in tree resin, citing the native Latin name of succinum (sūcinum, from sucus "juice").[13] "Amber is produced from a marrow discharged by trees belonging to the pine genus, like gum from the cherry, and resin from the ordinary pine. It is a liquid at first, which issues forth in considerable quantities, and is gradually hardened [...] Our forefathers, too, were of opinion that it is the juice of a tree, and for this reason gave it the name of 'succinum' and one great proof that it is the produce of a tree of the pine genus, is the fact that it emits a pine-like smell when rubbed, and that it burns, when ignited, with the odour and appearance of torch-pine wood."

He also states that amber is also found in Egypt and in India, and he even refers to the electrostatic properties of amber, by saying that "in Syria the women make the whorls of their spindles of this substance, and give it the name of harpax [from ἁρπάζω, "to drag"] from the circumstance that it attracts leaves towards it, chaff, and the light fringe of tissues."

Pliny says that the German name of amber was glæsum, "for which reason the Romans, when Germanicus Cæsar commanded the fleet in those parts, gave to one of these islands the name of Glæsaria, which by the barbarians was known as Austeravia". This is confirmed by the recorded Old High German glas and Old English glær for "amber" (c.f. glass). In Middle Low German, amber was known as berne-, barn-, börnstēn. The Low German term became dominant also in High German by the 18th century, thus modern German Bernstein besides Dutch Dutch barnsteen.

The Baltic Lithuanian term for amber is gintaras and Latvian dzintars. They, and the Slavic jantar or Hungarian gyanta ('resin'), are thought to originate from Phoenician jainitar ("sea-resin").

Early in the nineteenth century, the first reports of amber from North America came from discoveries in New Jersey along Crosswicks Creek near Trenton, at Camden, and near Woodbury.[3]

Legends

The origins of Baltic amber are associated with the Lithuanian legend about Juratė, the queen of the sea, who fell in love with Kastytis, a fisherman. According to one of the versions, her jealous father punished his daughter by destroying her amber palace and changing her into sea foam. The pieces of the Juratė’s palace can still be found on the Baltic shore. See also Jūratė and Kastytis.

Composition and formation

Amber is heterogeneous in composition, but consists of several resinous bodies more or less soluble in alcohol, ether and chloroform, associated with an insoluble bituminous substance. Amber is a macromolecule by free radical polymerization of several precursors in the labdane family, e.g. communic acid, cummunol, and biformene.[14][15] These labdanes are diterpenes (C20H32) and trienes, equipping the organic skeleton with three alkene groups for polymerization. As amber matures over the years, more polymerization takes place as well as isomerization reactions, crosslinking and cyclization.

Heated above 200 °C (392 °F), amber suffers decomposition, yielding an oil of amber, and leaving a black residue which is known as "amber colophony", or "amber pitch"; when dissolved in oil of turpentine or in linseed oil this forms "amber varnish" or "amber lac".[14]

Formation

Molecular polymerization, resulting from high pressures and temperatures produced by overlying sediment, transforms the resin first into copal. Sustained heat and pressure drives off terpenes and results in the formation of amber.[16]

For this to happen, the resin must be resistant to decay. Many trees produce resin, but in the majority of cases this deposit is broken down by physical and biological processes. Exposure to sunlight, rain, microorganisms (such as bacteria and fungi), and extreme temperatures tends to disintegrate resin. For resin to survive long enough to become amber, it must be resistant to such forces or be produced under conditions that exclude them.[17]

Botanical origin

Fossil resins from Europe fall into two categories, the famous Baltic ambers and another that resembles the Agathis group. Fossil resins from the Americas and Africa are closely related to the modern genus Hymenaea,[18] while Baltic ambers are thought to be fossil resins from Sciadopityaceae family plants that used to live in north Europe.[19]

Inclusions

The abnormal development of resin in living trees (succinosis) can result in the formation of amber.[20] Impurities are quite often present, especially when the resin dropped onto the ground, so the material may be useless except for varnish-making. Such impure amber is called firniss.

Such inclusion of other substances can cause amber to have an unexpected color. Pyrites may give a bluish color. Bony amber owes its cloudy opacity to numerous tiny bubbles inside the resin.[21] However, so-called black amber is really only a kind of jet.

In darkly clouded and even opaque amber, inclusions can be imaged using high-energy, high-contrast, high-resolution X-rays.[22]

Extraction and processing

Distribution and mining

Amber is globally distributed, mainly in rocks of Cretaceous age or younger. Historically, the Samland coast west of Königsberg in Prussia was the world's leading source of amber. First mentions of amber deposits here date back to the 12th century.[23] About 90% of the world's extractable amber is still located in that area, which became the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia in 1946.[24]

Pieces of amber torn from the seafloor are cast up by the waves, and collected by hand, dredging, or diving. Elsewhere, amber is mined, both in open works and underground galleries. Then nodules of blue earth have to be removed and an opaque crust must be cleaned off, which can be done in revolving barrels containing sand and water. Erosion removes this crust from sea-worn amber.[21]

Caribbean amber, especially Dominican blue amber, is mined through bell pitting, which is dangerous due to the risk of tunnel collapse.[25]

Treatment

The Vienna amber factories, which use pale amber to manufacture pipes and other smoking tools, turn it on a lathe and polish it with whitening and water or with rotten stone and oil. The final luster is given by friction with flannel.[21]

When gradually heated in an oil-bath, amber becomes soft and flexible. Two pieces of amber may be united by smearing the surfaces with linseed oil, heating them, and then pressing them together while hot. Cloudy amber may be clarified in an oil-bath, as the oil fills the numerous pores to which the turbidity is due. Small fragments, formerly thrown away or used only for varnish, are now used on a large scale in the formation of "ambroid" or "pressed amber".[21]

The pieces are carefully heated with exclusion of air and then compressed into a uniform mass by intense hydraulic pressure, the softened amber being forced through holes in a metal plate. The product is extensively used for the production of cheap jewelry and articles for smoking. This pressed amber yields brilliant interference colors in polarized light. Amber has often been imitated by other resins like copal and kauri gum, as well as by celluloid and even glass. Baltic amber is sometimes colored artificially, but also called "true amber".[21]

Appearance

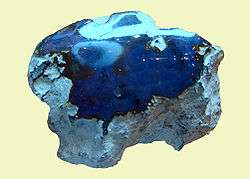

Amber occurs in a range of different colors. As well as the usual yellow-orange-brown that is associated with the color "amber", amber itself can range from a whitish color through a pale lemon yellow, to brown and almost black. Other uncommon colors include red amber (sometimes known as "cherry amber"), green amber, and even blue amber, which is rare and highly sought after.

Yellow amber is a hard, translucent, yellow, orange, or brown fossil resin from evergreen trees. Known to the Iranians by the Pahlavi compound word kah-ruba (from kah “straw” plus rubay “attract, snatch,” referring to its electrical properties), which entered Arabic as kahraba' or kahraba (which later became the Arabic word for electricity, كهرباء kahrabā'), it too was called amber in Europe (Old French and Middle English ambre). Found along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea, yellow amber reached the Middle East and western Europe via trade. Its coastal acquisition may have been one reason yellow amber came to be designated by the same term as ambergris. Moreover, like ambergris, the resin could be burned as an incense. The resin's most popular use was, however, for ornamentation—easily cut and polished, it could be transformed into beautiful jewelry. Much of the most highly prized amber is transparent, in contrast to the very common cloudy amber and opaque amber. Opaque amber contains numerous minute bubbles. This kind of amber is known as "bony amber".[26]

Although all Dominican amber is fluorescent, the rarest Dominican amber is blue amber. It turns blue in natural sunlight and any other partially or wholly ultraviolet light source. In long-wave UV light it has a very strong reflection, almost white. Only about 100 kg (220 lb) is found per year, which makes it valuable and expensive.[27]

Sometimes amber retains the form of drops and stalactites, just as it exuded from the ducts and receptacles of the injured trees.[21] It is thought that, in addition to exuding onto the surface of the tree, amber resin also originally flowed into hollow cavities or cracks within trees, thereby leading to the development of large lumps of amber of irregular form.

Classification

Amber can be classified into several forms. Most fundamentally, there are two types of plant resin with the potential for fossilization. Terpenoids, produced by conifers and angiosperms, consist of ring structures formed of isoprene (C5H8) units.[2] Phenolic resins are today only produced by angiosperms, and tend to serve functional uses. The extinct medullosans produced a third type of resin, which is often found as amber within their veins.[2] The composition of resins is highly variable; each species produces a unique blend of chemicals which can be identified by the use of pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.[2] The overall chemical and structural composition is used to divide ambers into five classes.[28][29] There is also a separate classification of amber gemstones, according to the way of production.

Class I

This class is by far the most abundant. It comprises labdatriene carboxylic acids such as communic or ozic acids.[28] It is further split into three sub-classes. Classes Ia and Ib utilize regular labdanoid diterpenes (e.g. communic acid, communol, biformenes), while Ic uses enantio labdanoids (ozic acid, ozol, enantio biformenes).[30]

Ia

Includes Succinite (= 'normal' Baltic amber) and Glessite.[29] Have a communic acid base. They also include much succinic acid.[28]

Baltic amber yields on dry distillation succinic acid, the proportion varying from about 3% to 8%, and being greatest in the pale opaque or bony varieties. The aromatic and irritating fumes emitted by burning amber are mainly due to this acid. Baltic amber is distinguished by its yield of succinic acid, hence the name succinite. Succinite has a hardness between 2 and 3, which is rather greater than that of many other fossil resins. Its specific gravity varies from 1.05 to 1.10.[14] It can be distinguished from other ambers via IR spectroscopy due to a specific carbonyl absorption peak. IR spectroscopy can detect the relative age of an amber sample. Succinic acid may not be an original component of amber, but rather a degradation product of abietic acid.[31]

Ib

Like class Ia ambers, these are based on communic acid; however, they lack succinic acid.[28]

Ic

This class is mainly based on enantio-labdatrienonic acids, such as ozic and zanzibaric acids.[28] Its most familiar representative is Dominican amber.[2]

Dominican amber differentiates itself from Baltic amber by being mostly transparent and often containing a higher number of fossil inclusions. This has enabled the detailed reconstruction of the ecosystem of a long-vanished tropical forest.[32] Resin from the extinct species Hymenaea protera is the source of Dominican amber and probably of most amber found in the tropics. It is not "succinite" but "retinite".[33]

Class II

These ambers are formed from resins with a sesquiterpenoid base, such as cadinene.[28]

Class III

These ambers are polystyrenes.[28]

Class IV

Class IV is something of a wastebasket; its ambers are not polymerized, but mainly consist of cedrene-based sesquiterpenoids.[28]

Class V

Class V resins are considered to be produced by a pine or pine relative. They comprise a mixture of diterpinoid resins and n-alkyl compounds. Their type mineral is highgate copalite.[29]

Geological record

The oldest amber recovered dates to the Upper Carboniferous period (320 million years ago).[2][34] Its chemical composition makes it difficult to match the amber to its producers – it is most similar to the resins produced by flowering plants; however, there are no flowering plant fossils until the Cretaceous, and they were not common until the Upper Cretaceous. Amber becomes abundant long after the Carboniferous, in the Early Cretaceous, 150 million years ago,[2] when it is found in association with insects. The oldest amber with arthropod inclusions comes from the Levant, from Lebanon and Jordan. This amber, roughly 125–135 million years old, is considered of high scientific value, providing evidence of some of the oldest sampled ecosystems.[35]

In Lebanon more than 450 outcrops of Lower Cretaceous amber were discovered by Dany Azar[36] a Lebanese paleontologist and entomologist. Among these outcrops 20 have yielded biological inclusions comprising the oldest representatives of several recent families of terrestrial arthropods. Even older, Jurassic amber has been found recently in Lebanon as well. Many remarkable insects and spiders were recently discovered in the amber of Jordan including the oldest zorapterans, clerid beetles, umenocoleid roaches, and achiliid planthoppers.[35]

Baltic amber or succinite (historically documented as Prussian amber[14]) is found as irregular nodules in marine glauconitic sand, known as blue earth, occurring in the Lower Oligocene strata of Sambia in Prussia (in historical sources also referred to as Glaesaria).[14] After 1945 this territory around Königsberg was turned into Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia, where amber is now systematically mined.[37]

It appears, however, to have been partly derived from older Eocene deposits and it occurs also as a derivative phase in later formations, such as glacial drift. Relics of an abundant flora occur as inclusions trapped within the amber while the resin was yet fresh, suggesting relations with the flora of Eastern Asia and the southern part of North America. Heinrich Göppert named the common amber-yielding pine of the Baltic forests Pinites succiniter, but as the wood does not seem to differ from that of the existing genus it has been also called Pinus succinifera. It is improbable, however, that the production of amber was limited to a single species; and indeed a large number of conifers belonging to different genera are represented in the amber-flora.[21]

Paleontological significance

Amber is a unique preservational mode, preserving otherwise unfossilizable parts of organisms; as such it is helpful in the reconstruction of ecosystems as well as organisms;[38] the chemical composition of the resin, however, is of limited utility in reconstructing the phylogenetic affinity of the resin producer.[2]

Amber sometimes contains animals or plant matter that became caught in the resin as it was secreted. Insects, spiders and even their webs, annelids, frogs,[39] crustaceans, bacteria and amoebae,[40] marine microfossils,[41] wood, flowers and fruit, hair, feathers and other small organisms have been recovered in ambers dating to 130 million years ago.[2]

In August 2012, two mites preserved in amber were determined to be the oldest animals ever to have been found in the substance; the mites are 230 million years old and were discovered in north-eastern Italy.[42]

Use

Amber has been used since prehistory (Solutrean) in the manufacture of jewelry and ornaments, and also in folk medicine. Amber also forms the flavoring for akvavit liquor. Amber has been used as an ingredient in perfumes.

Jewelry

Amber has been used since the stone age, from 13,000 years ago.[2] Amber ornaments have been found in Mycenaean tombs and elsewhere across Europe.[43] To this day it is used in the manufacture of smoking and glassblowing mouthpieces.[44][45] Amber's place in culture and tradition lends it a tourism value; Palanga Amber Museum is dedicated to the fossilized resin.

Historic medicinal uses

Amber has long been used in folk medicine for its purported healing properties.[46] Amber and extracts were used from the time of Hippocrates in ancient Greece for a wide variety of treatments through the Middle Ages and up until the early twentieth century.

Scent of amber and amber perfumery

In ancient China it was customary to burn amber during large festivities. If amber is heated under the right conditions, oil of amber is produced, and in past times this was combined carefully with nitric acid to create "artificial musk" – a resin with a peculiar musky odor.[47] Although when burned, amber does give off a characteristic "pinewood" fragrance, modern products, such as perfume, do not normally use actual amber due to the fact that fossilized amber produces very little scent. In perfumery, scents referred to as “amber” are often created and patented[48][49] to emulate the opulent golden warmth of the fossil.[50]

The modern name for amber is thought to come from the Arabic word, ambar, meaning ambergris.[51][52] Ambergris is the waxy aromatic substance created in the intestines of sperm whales and was used in making perfumes both in ancient times as well as modern.

The scent of amber was originally derived from emulating the scent of ambergris and/or labdanum but due to the endangered species status of the sperm whale the scent of amber is now largely derived from labdanum.[53] The term “amber” is loosely used to describe a scent that is warm, musky, rich and honey-like, and also somewhat oriental and earthy. It can be synthetically created or derived from natural resins. When derived from natural resins it is most often created out of labdanum. Benzoin is usually part of the recipe. Vanilla and cloves are sometimes used to enhance the aroma.

"Amber" perfumes may be created using combinations of labdanum, benzoin resin, copal (itself a type of tree resin used in incense manufacture), vanilla, Dammara resin and/or synthetic materials.[47]

Imitation

Imitation made in natural resins

Young resins, these are used as imitations:[54]

- Kauri resin from trees Agathis australis, New Zealand.

- The copals (subfossil resins). The African and American (Colombia) copals from Leguminosae trees family (genus Hymenaea). Amber of the Dominican or Mexican type (Class I of fossil resins). Copals from Manilia (Indonesia) and from New Zealand from trees of the genus Agathis (Araucariaceae family)

- Other fossil resins: burmite in Burma, rumenite in Romania, simetite in Sicilia.

- Other natural resins — cellulose or chitin, etc.

Imitations made of plastics

Plastics, these are used as imitations:[55]

- Stained glass (inorganic material) and other ceramic materials

- Celluloid

- Cellulose nitrate (obtain first time in 1833[56]) — a product of treatment of cellulose with nitration mixture.[57]

- Acetylcellulose (not in the use at present)

- Galalith or «artificial horn» (condensation product of casein and formaldehyde), other trade names: Alladinite, Erinoid, Lactoid.[56]

- Casein — a conjugated protein forming from the casein precursor – caseinogen.[58]

- Resolane (phenolic resins or phenoplasts, not in the use at present)

- Bakelite resine (resol, phenolic resins), product from Africa are known under the misleading name: «African amber».

- Carbamide resins — melamine, formaldehyde and urea-formaldehyde resins.[57]

- Epoxy novolac (phenolic resins), non officially name: «antique amber», not in the use at present

- Polyesters (Polish amber imitation) with styrene. Ex.: unsaturated polyester resins (polymals) are produced by Chemical Industrial Works «Organika» in Sarzyna, Poland; estomal are produced by Laminopol firm. Polybern or sticked amber is artificial resins the curled chips are obtained, whereas in the case of amber – small scraps. «African amber» (polyester, synacryl is then probably other name of the same resine) are produced by Reichhold firm; Styresol trade mark or alkid resin (used in Russia, Reichhold, Inc. patent, 1948.[59]

- Polyethylene

- Eepoxide resins

- Polystyrene and polystyrene-like polymers (vinyl polymers).[60]

- The resins of acrylic type (vinyl polymers[60]), especially polymethyl methacrylate PMMA (trade mark Plexiglass, metaplex).

See also

References

- ↑ Jessamyn Reeves-Brown (November 1997). "Mastering New Materials: Commissioning an Amber Bow". Strings (65). Archived from the original on 14 May 2004. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Grimaldi, D. (2009). "Pushing Back Amber Production". Science. 326 (5949): 51–2. Bibcode:2009Sci...326...51G. doi:10.1126/science.1179328. PMID 19797645.

- 1 2 "Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) Encyclopedia of New Jersey, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0813533252.

- ↑ Poinar GO, Poinar R. (1995) The quest for life in amber. Basic Books, ISBN 0-201-48928-7, p. 133

- 1 2 Harper, Douglas. "amber". Online Etymology Dictionary. and "amber". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary, D N MacKenzie, Oxford University Press, 1971, ISBN 0 19 713559 5

- ↑ see: Abu Zaid al Hassan from Siraf & Sulaiman the Merchant (851), Silsilat-al-Tawarikh (travels in Asia).

- ↑ Homeric (Iliad 6.513, 19.398). The feminine ἠλεκτρίς being later used as a name of the Moon. King, Rev. C.W. (1867). The Natural History of Gems or Decorative Stones. Cambridge (UK). p. 315.

- ↑ The derivation of the modern term "electric" from the Greek word for amber dates to the 1600 (Latin electricus "amber-like", in De Magnete by William Gilbert). Heilbron, J.L. (1979). Electricity in the 17th and 18th Centuries: A Study of Early Modern Physics. University of California Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-520-03478-5.. The word "electron" (for the fundamental particle) was coined in 1891 by the Irish physicist George Stoney whilst analyzing elementary charges for the first time. Aber, Susie Ward. "Welcome to the World of Amber". Emporia State University. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.. "Origin of word Electron". Patent-invent.com. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ Michael R. Collings, Gemlore: An Introduction to Precious and Semi-Precious Stones, 2009, p. 20

- ↑ Natural History 37.11.

- ↑ Natural History IV.27.13 or IV.13.95 in the Loeb edition.

- ↑ succinic acid as well as succinite, a term given to a particular type of amber by James Dwight Dana

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rudler 1911, p. 792.

- ↑ Manuel Villanueva-García, Antonio Martínez-Richa, and Juvencio Robles Assignment of vibrational spectra of labdatriene derivatives and ambers: A combined experimental and density functional theoretical study Arkivoc (EJ-1567C) pp. 449–458

- ↑ Rice, Patty C. (2006). Amber: Golden Gem of the Ages. 4th Ed. AuthorHouse. ISBN 1-4259-3849-3.

- ↑ Poinar, George O. (1992) Life in amber. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, p. 12, ISBN 0804720010

- ↑ Lambert, JB; Poinar Jr, GO (2002). "Amber: the organic gemstone". Accounts of Chemical Research. 35 (8): 628–36. doi:10.1021/ar0001970. PMID 12186567.

- ↑ Wolfe, A. P.; Tappert, R.; Muehlenbachs, K.; Boudreau, M.; McKellar, R. C.; Basinger, J. F.; Garrett, A. (30 June 2009). "A new proposal concerning the botanical origin of Baltic amber". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1672): 3403–3412. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0806. PMC 2817186

. PMID 19570786.

. PMID 19570786. - ↑ Sherborn, Charles Davies. "Natural Science: A Monthly Review of Scientific Progress, Volume 1".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rudler 1911, p. 793.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (1 April 2008). "BBC News, " Secret 'dino bugs' revealed", 1 April 2008". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 August 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ "The History of Russian Amber, Part 1: The Beginning", Ambery.net

- ↑ Amber Trade and the Environment in the Kaliningrad Oblast. Gurukul.ucc.american.edu. Retrieved on 19 September 2012.

- ↑ Wichard, Wilfred and Weitschat, Wolfgang (2004) Im Bernsteinwald. – Gerstenberg Verlag, Hildesheim, ISBN 3-8067-2551-9

- ↑ "Amber". (1999). In G. W. Bowersock, Peter Brown, Oleg Grabar (eds.) Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674511735.

- ↑ Manuel A. Iturralde-Vennet (2001). "Geology of the Amber-Bearing Deposits of the Greater Antilles" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 37 (3): 141–167. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Anderson, K; Winans, R; Botto, R (1992). "The nature and fate of natural resins in the geosphere—II. Identification, classification and nomenclature of resinites". Organic Geochemistry. 18 (6): 829–841. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(92)90051-X.

- 1 2 3 Anderson, K; Botto, R (1993). "The nature and fate of natural resins in the geosphere—III. Re-evaluation of the structure and composition of Highgate Copalite and Glessite". Organic Geochemistry. 20 (7): 1027. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(93)90111-N.

- ↑ Anderson, Ken B. (1996). "New Evidence Concerning the Structure, Composition, and Maturation of Class I (Polylabdanoid) Resinites". Amber, Resinite, and Fossil Resins. ACS Symposium Series. 617. pp. 105–129. doi:10.1021/bk-1995-0617.ch006. ISBN 0-8412-3336-5.

- ↑ Shashoua, Yvonne (2007). "Degradation and inhibitive conservation of Baltic amber in museum collections" (PDF). Department of Conservation, The National Museum of Denmark. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- ↑ George Poinar, Jr. and Roberta Poinar, 1999. The Amber Forest: A Reconstruction of a Vanished World, (Princeton University Press) ISBN 0-691-02888-5

- ↑ Grimaldi, D. A. (1996) Amber – Window to the Past. – American Museum of Natural History, New York, ISBN 0810919664

- ↑ Bray, P. S.; Anderson, K. B. (2009). "Identification of Carboniferous (320 Million Years Old) Class Ic Amber". Science. 326 (5949): 132–134. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..132B. doi:10.1126/science.1177539. PMID 19797659.

- 1 2 Poinar, P.O., Jr., and R.K. Milki (2001) Lebanese Amber: The Oldest Insect Ecosystem in Fossilized Resin. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis. ISBN 0-87071-533-X.

- ↑ Azar, Dany (2012). "Lebanese amber: a "Guinness Book of Records"". Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis. 111: 44–60.

- ↑ Langenheim, Jean (2003). Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany. Timber Press Inc. ISBN 0-88192-574-8.

- ↑ BBC – Radio 4 – Amber. Db.bbc.co.uk (16 February 2005). Retrieved on 23 April 2011.

- ↑ "Scientist: Frog could be 25 million years old". MSNBC. 16 February 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ Waggoner, Benjamin M. (13 July 1996). "Bacteria and protists from Middle Cretaceous amber of Ellsworth County, Kansas". PaleoBios. 17 (1): 20–26.

- ↑ Girard, V.; Schmidt, A.; Saint Martin, S.; Struwe, S.; Perrichot, V.; Saint Martin, J.; Grosheny, D.; Breton, G.; Néraudeau, D. (2008). "Evidence for marine microfossils from amber". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (45): 17426–17429. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10517426G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804980105. PMC 2582268

. PMID 18981417.

. PMID 18981417. - ↑ Kaufman, Rachel (28 August 2012). "Goldbugs". National Geographic.

- ↑ Curt W. Beck, Anthony Harding and Helen Hughes-Brock, "Amber in the Mycenaean World" The Annual of the British School at Athens, vol. 69 (November 1974), pp. 145-172. DOI:10.1017/S0068245400005505

- ↑ "Interview with expert pipe maker, Baldo Baldi. Accessed 10-12-09". Pipesandtobaccos.com. 11 February 2000. Archived from the original on 16 February 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ "Maker of amber mouthpiece for glass blowing pipes. Accessed 10-12-09". Steinertindustries.com. 7 May 2007. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ Lisa Markman (2009). "Teething: Facts and Fiction" (PDF). Pediatr. Rev. 30 (8): e59–e64. doi:10.1542/pir.30-8-e59. PMID 19648257.

- 1 2 Amber as an aphrodisiac. Aphrodisiacs-info.com. Retrieved on 19 September 2012.

- ↑ Thermer, Ernst T. "Saturated indane derivatives and processes for producing same" U.S. Patent 3,703,479, U.S. Patent 3,681,464, issue date 1972

- ↑ Perfume compositions and perfume articles containing one isomer of an octahydrotetramethyl acetonaphthone, John B. Hall, Rumson; James Milton Sanders, Eatontown U.S. Patent 3,929,677, Publication Date: 30 December 1975

- ↑ Sorcery of Scent: Amber: A perfume myth. Sorceryofscent.blogspot.com (30 July 2008). Retrieved on 23 April 2011.

- ↑ Aber, Susie Ward. "Welcome to the World of Amber". Emporia State University. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ "Origin of word Electron". Patent-invent.com. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ Gomes, Paula B, Mata, Vera G, Rodrigues, A E (2005). "Characterization of the Portuguese-Grown Cistus ladanifer Essential Oil" (PDF). Journal of Essential Oil Research. 17 (2): 160. doi:10.1080/10412905.2005.9698864.

- ↑ Matushevskaya 2013, pp. 11–13

- ↑ Matushevskaya 2013, pp. 13–19

- 1 2 Wagner-Wysiecka 2013, p. 30

- 1 2 Bogdasarov & Bogdasarov 2013, p. 38

- ↑ Bogdasarov & Bogdasarov 2013, p. 37

- ↑ Wagner-Wysiecka 2013, p. 31

- 1 2 Wagner-Wysiecka 2013, p. 32

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rudler, Frederick William (1911). "Amber (resin)". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 792–794.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rudler, Frederick William (1911). "Amber (resin)". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 792–794.

Bibliography

- Bogdasarov, Albert; Bogdasarov, Maksim (2013). "Forgery and simulations from amber" [Подделки и имитация янтаря]. In Kostjashova, Z. V. Янтарь и его имитации Материалы международной научно-практической конференции 27 июня 2013 года [Amber and its imitations] (in Russian). Kaliningrad: Kaliningrad Amber Museum, Ministry of Culture (Kaliningrad region, Russia). p. 113. ISBN 978-5-903920-26-6.

- Matushevskaya, Aniela (2013). "Natural and artificial resins – chosen aspects of structure and properties". In Kostjashova, Z. V. Янтарь и его имитации Материалы международной научно-практической конференции 27 июня 2013 года [Amber and its imitations] (in Russian). Kaliningrad: Kaliningrad Amber Museum, Ministry of Culture (Kaliningrad region, Russia). p. 113. ISBN 978-5-903920-26-6.

- Wagner-Wysiecka, Eva (2013). "Amber imitations through the eyes of a chemist" [Имитация янтаря глазами химика]. In Kostjashova, Z. V. Янтарь и его имитации Материалы международной научно-практической конференции 27 июня 2013 года [Amber and its imitations] (in Russian). Kaliningrad: Kaliningrad Amber Museum, Ministry of Culture (Kaliningrad region, Russia). p. 113. ISBN 978-5-903920-26-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Farlang many full text historical references on Amber Theophrastus, George Frederick Kunz, and special on Baltic amber.

- IPS Publications on amber inclusions International Paleoentomological Society: Scientific Articles on amber and its inclusions

- Webmineral on Amber Physical properties and mineralogical information

- Mindat Amber Image and locality information on amber

- NY Times 40 million year old extinct bee in Dominican amber