Oldowan

| |

| Geographical range | Afro-Eurasia |

|---|---|

| Period | Lower Paleolithic |

| Dates | 2.6 million years BP – 1.7 million years BP |

| Major sites | Olduvai Gorge |

| Preceded by | Pliocene |

| Followed by | Acheulean, Riwat |

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

|

↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

|

Lower Paleolithic

Middle Paleolithic

Upper Paleolithic

|

| ↓ Mesolithic ↓ Stone Age |

The Oldowan, sometimes spelled Olduwan, is the earliest stone tool archaeological industry in prehistory. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower Paleolithic period, 2.6 million years ago up until 1.7 million years ago, by ancient hominins across much of Africa, South Asia, the Middle East and Europe. This technological industry was followed by the more sophisticated Acheulean industry.

The term "Oldowan" is taken from the site of Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, where the first Oldowan lithics were discovered by the archaeologist Louis Leakey in the 1930s. However, some contemporary archaeologists and palaeoanthropologists prefer to use the term "Mode 1" tools to designate pebble tool industries (including Oldowan), with "Mode 2" designating bifacially-worked tools (including Acheulean handaxes), "Mode 3" designating prepared-core tools, and so forth.[1]

Classification of Oldowan tools is still somewhat contentious. Mary Leakey was the first to create a system to classify Oldowan assemblages, and built her system based on prescribed use. The system included choppers, scrapers, and pounders.[2][3] However, more recent classifications of Oldowan assemblages have been made that focus primarily on manufacture due to the problematic nature of assuming use from stone artefacts. An example is Isaac et al.'s tri-modal categories of "Flaked Pieces" (cores/ choppers), "Detached Pieces" (flakes and fragments), "Pounded Pieces" (cobbles utilized as hammerstones, etc.) and "Unmodified Pieces" (manuports, stones transported to sites).[4] Oldowan tools are sometimes called "pebble tools", so named because the blanks chosen for their production already resemble, in pebble form, the final product.[5]

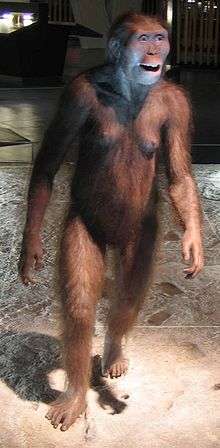

It is not known for sure which hominin species actually created and used Oldowan tools. Its emergence is often associated with the species Australopithecus garhi[6] and its flourishing with early species of Homo such as H. habilis and H. ergaster. Early Homo erectus appears to inherit Oldowan technology and refines it into the Acheulean industry beginning 1.7 million years ago.[7]

Dates and ranges

The oldest known Oldowan tools have been found in Gona, Ethiopia, and are dated to about 2.6 mya.[8]

The use of tools by apes including chimpanzees[9] and orangutans[10] can be used to argue in favour of tool-use as an ancestral feature of the hominin family.[11] Tools made from bone, wood, or other organic materials were therefore in all probability used before the Oldowan.[12] Oldowan stone tools are simply the oldest recognisable tools which have been preserved in the archaeological record.

There is a flourishing of Oldowan tools in eastern Africa, spreading to southern Africa, between 2.4 and 1.7 mya. At 1.7 mya., the first Acheulean tools appear even as Oldowan assemblages continue to be produced. Both technologies are occasionally found in the same areas, dating to the same time periods. This realisation required a rethinking of old cultural sequences in which the more "advanced" Acheulean was supposed to have succeeded the Oldowan. The different traditions may have been used by different species of hominins living in the same area, or multiple techniques may have been used by an individual species in response to different circumstances.

Sometime before 1.8 mya Homo erectus had spread outside of Africa, reaching as far east as Java by 1.8 mya[13] and in Northern China by 1.66 mya.[14] In these newly colonised areas, no Acheulean assemblages have been found. In China, only "Mode 1" Oldowan assemblages were produced, while in Indonesia stone tools from this age are unknown.

By 1.8 mya early Homo was present in Europe, as shown by the discovery of fossil remains and Oldowan tools in Dmanisi, Georgia.[15] Remains of their activities have also been excavated in Spain at sites in the Guadix-Baza basin[16] and near Atapuerca.[17] Most early European sites yield "Mode 1" or Oldowan assemblages. The earliest Acheulean sites in Europe only appear around 0.5 mya. In addition, the Acheulean tradition does not seem to spread to Eastern Asia.[18] It is unclear from the archaeological record when the production of Oldowon technologies ended. Other tool-making traditions seem to have supplanted Oldowon technologies by 0.25 mya.

The tools

Manufacture of the tools

To obtain an Oldowan tool, a roughly spherical hammerstone is struck on the edge, or striking platform, of a suitable core rock to produce a conchoidal fracture with sharp edges useful for various purposes. The process is often called lithic reduction. The chip removed by the blow is the flake. Below the point of impact on the core is a characteristic bulb with fine fissures on the fracture surface. The flake evidences ripple marks.

The materials of the tools were for the most part quartz, quartzite, basalt, or obsidian, and later flint and chert. Any rock that can hold an edge will do. The main source of these rocks is river cobbles, which provide both hammer stones and striking platforms. The earliest tools were simply split cobbles. It is not always clear which is the flake. Later tool-makers clearly identified and reworked flakes. Complaints that artifacts could not be distinguished from naturally fractured stone have helped spark careful studies of Oldowon techniques. These techniques have now been duplicated many times by archaeologists and other knappers, making misidentification of archaeological finds less likely.

Use of bone tools by hominins also producing Oldowan tools is known from Swartkrans, where a bone shaft with a polished point was discovered in Member (layer) I, dated 1.8–1.5 mya. The Osteodontokeratic industry, the "bone-tooth-horn" industry hypothesized by Raymond Dart, is less certain.

Shapes and uses of the tools

Mary Leakey classified the Oldowan tools as Heavy Duty, Light Duty, Utilized Pieces and Debitage, or waste.[19] Heavy-duty tools are mainly cores. A chopper has an edge on one side. It is unifacial if the edge was created by flaking on one face of the core, or bifacial if on two. Discoid tools are roughly circular with a peripheral edge. Polyhedral tools are edged in the shape of a polyhedron. In addition there are spheroidal hammer stones.

Light-duty tools are mainly flakes. There are scrapers, awls (with points for boring) and burins (with points for engraving). Some of these functions belong also to heavy-duty tools. For example, there are heavy-duty scrapers.

Utilized pieces are tools that began with one purpose in mind but were utilized opportunistically.

Oldowan tools were probably used for many purposes, which have been discovered from observation of modern apes and hunter-gatherers. Nuts and bones are cracked by hitting them with hammer stones on a stone used as an anvil. Battered and pitted stones testify to this possible use.

Heavy-duty tools could be used as axes for woodworking. Both choppers and large flakes were probably used for this purpose. Once a branch was separated, it could be scraped clean with a scraper, or hollowed with pointed tools. Such uses are attested by characteristic microscopic alterations of edges used to scrape wood. Oldowan tools could also have been used for preparing hides. Hides must be cut by slicing, piercing and scraping it clean of residues. Flakes are most suitable for this purpose.

Lawrence Keeley, following in the footsteps of Sergei Semenov, conducted microscopic studies (with a high-powered optical microscope) on the edges of tools manufactured de novo and used for the originally speculative purposes described above. He found that the marks were characteristic of the use and matched marks on prehistoric tools. Studies of the cut marks on bones using an electron microscope produce a similar result.

Abbevillian

Abbevillian is a currently obsolescent name for a tool tradition that is increasingly coming to be called Oldowan. The label Abbevillian prevailed until the Leakey family discovered older (yet similar) artifacts at Olduvai Gorge (a.k.a. Oldupai Gorge) and promoted the African origin of man. Oldowan soon replaced Abbevillian in describing African and Asian lithics. The term Abbevillian is still used but is now restricted to Europe. The label, however, continues to lose popularity as a scientific designation.

In the late 20th century, discovery of the discrepancies in date caused a crisis of definition. If Abbevillian did not necessarily precede Acheulean and both traditions had flakes and bifaces, how was the difference to be defined? It was in this spirit that many artifacts formerly considered Abbevillian were labeled Acheulean. In consideration of the difficulty, some preferred to name both phases Acheulean. When the topic of Abbevillian came up, it was simply put down as a phase of Acheulean. Whatever was from Africa was Oldowan, and whatever from Europe, Acheulean.

The solution to the definition problem is stated in the article on Acheulean. The difference is to be defined in terms of complexity. Simply struck tools are Oldowan. Retouched, or reworked tools are Acheulean. Retouching is a second working of the artifact. The manufacturer first creates an Oldowan tool. Then he reworks or retouches the edges by removing very small chips so as to straighten and sharpen the edge. Typically but not necessarily the reworking is accomplished by pressure flaking.

The pictures in the introduction to this article are mainly labeled Acheulean, but this is the now false Acheulean, which also includes Abbevillian. The artifacts shown are clearly in the Oldowan tradition. One or two of the more complex bifaces may have edges made straighter by a large percussion or two, but there is no sign of pressure flaking as depicted. The pictures included with this subsection show the difference.

The tool users

Current anthropological thinking is that Oldowan tools were made by late Australopithecus and early Homo. Homo habilis was named "skillful" because it was considered the earliest tool-using human ancestor. Indeed, the genus Homo was in origin intended to separate tool-using species from their tool-less predecessors, hence the name of Australopithecus garhi, garhi meaning "surprise", a tool-using Australopithecine discovered in 1996 and described as the "missing link" between the Australopithecus and Homo genera. There is also evidence that some species of Paranthropus utilized stone tools.[20]

There is presently no evidence to show that Oldowan tools were the sole creation of members of the Homo line or that the ability to produce them was a special characteristic of only our ancestors. Research on tool use by modern wild chimpanzees in West Africa shows there is an operational sequence when chimpanzees use lithic implements to crack nuts. In the course of nut cracking, sometimes they will create unintentional flakes. Although the morphology of chimpanzees' hammer is different from Oldowan hammer, chimpanzees' ability to use stone tools indicates that the earliest lithic industries were probably not produced by only one kind of hominin species.[21]

The makers of Oldowan tools were mainly right-handed.[22] "Handedness" (lateralization) had thus already evolved, though it is not clear how related to modern lateralization it was, since other animals show handedness as well.

In the mid-1970s, Glynn Isaac touched off a debate by proposing that human ancestors of this period had a "place of origin" and that they foraged outward from this home base, returning with high quality food to share and to be processed. Over the course of the last 30 years, a variety of competing theories about how foraging occurred have been proposed, each one implying certain kinds of social strategy. The available evidence from the distribution of tools and remains is not enough to decide which theories are the most probable. However, three main groups of theories predominate.

- Glynn Isaac's model became the Central Forage Point, as he responded to critics that accused him of attributing too much "modern" behavior to early hominins with relatively free-form searches outward.

- A second group of models took modern chimpanzee behavior as a starting point, having the hominids use relatively fixed routes of foraging, and leaving tools where it was best to do so on a constant track.

- A third group of theories had relatively loose bands scouring the range, taking care to move carcasses from dangerous death sites and leaving tools more or less at random.

Each group of models implies different grouping and social strategies, from the relative altruism of central base models to the relatively disjointed search models. (See also central foraging theory, scavenging station model, Lewis Binford)

Most models rely on social and communication networks to hold the band together. These social networks range from requiring no more communication than modern primates, to requiring more sophisticated sharing and teaching. At present, no evidence has been found that sharply divides these theories.

Hominins probably lived in social groups that had contact with others. This conclusion is supported by the large number of bones at many sites, too large to be the work of one individual, and all of the scatter patterns implying many different individuals. Since modern primates in Africa have fluid boundaries between groups, as individuals enter, become the focus of bands, and others leave, it is also probable that the tools we find are the result of many overlapping groups working the same territories, and perhaps competing over them. Because of the huge expanse of time and the multiplicity of species associated with possible Oldowan tools, it is difficult to be more precise than this, since it is almost certain that different social groupings were used at different times and in different places.

There is also the question of what mix of hunting, gathering and scavenging the tool users employed. Early models focused on the tool users as hunters. The animals butchered by the tools include waterbuck, hartebeest, springbok, pig and zebra. However, the disposition of the bones allows some question about hominin methods of obtaining meat. That they were omnivores is unquestioned, as the digging implement and the probable use of hammer stones to smash nuts indicate. Lewis Binford first noticed that the bones at Olduvai contained a disproportionately high incidence of extremities, which are low in food substance. He concluded other predators had taken the best meat, and the hominins had only scavenged. The counter view is that while hunting many large animals would be beyond the reach of an individual human, groups could bring down larger game, as pack hunting animals are capable of doing. Moreover, since many animals both hunt and scavenge, it is possible that hominins hunted smaller animals, but were not above driving carnivores from larger kills, as they probably were driven from kills themselves from time to time.

Sites and archaeologists

A complete catalog of Oldowan sites would be too extensive for listing here. Some of the better-known sites include the following:

Africa

Ethiopia

Afar Triangle

Sites in the Gona river system in the Hadar region of the Afar triangle, excavated by Helene Roche, J. W. Harris and Sileshi Semaw, yielded some of the oldest known Oldowan assemblages, dating to about 2.6 million years ago. Raw material analysis done by Semaw showed that some assemblages in this region are biased towards a certain material (e.g.: 70% of the artifacts at sites EG10 and EG12 were composed of trachyte) indicating a selectivity in the quality of stone used.[23] Recent excavations have yielded tools in association with cut-marked bones, indicating that Oldowan were used in meat-processing or -acquiring activities.

Omo River basin

The second oldest known Oldowan tool site comes from the Shungura formation of the Omo River basin. This formation documents the sediments of the Plio-Pleistocene and provides a record of the hominins that lived there. Lithic assemblages have been classified as Oldowan in members E and F in the lower Omo basin. Although there have been lithic assemblages found in multiple sites in these areas, only the Omo sites 57 and 123 in member F are accepted as hominin lithic remains. The assemblages at Omo sites 71 and 84 in member E do not show evidence of hominin modification and are therefore classified as natural assemblages.[24]

The tools are never found in direct association with the hominins, but archaeologists believe that they would be the strongest candidates for tool manufacture. There are no hominins in those layers, but the same layers elsewhere in the Omo valley contain Paranthropus and early Homo fossils. Paranthropus occurs in the preceding layers. In the last layer at 1.4 million years ago is only Homo erectus.

Egypt

Along the Nile River, within the 100 foot terrace, evidence of Chellean or Oldowan cultures has been found.[25]

Kenya

Kanjera South, part of the Kanjera site complex, is located on the Homa Peninsula.[26] The site is estimated around 2 million years old.[27] One of the significant excavations, in the area, is Leakey’s expedition in 1932-35.[26] In 1995, Oldowan and Plio-Pleistocene faunal remains surfaced from the site.[26] There has been fieldwork to understand the geochronology of Kanjera.[26]

East Turkana

The numerous Koobi Fora sites on the east side of Lake Turkana are now part of Sibiloi National Park. Sites were initially excavated by Richard Leakey, Meave Leakey, Jack Harris, Glynn Isaac and others. Currently the artifacts found are classified as Oldowan or KBS Oldowan dated from 1.9–1.7 mya, Karari (or "advanced Oldowan") dated to 1.6–1.4 mya, and some early Acheulean at the end of the Karari. Over 200 hominins have been found, including Australopithecus and Homo.

Tanzania

Olduvai Gorge

The Oldowan industry is named after discoveries made in the Olduvai Gorge of Tanzania in east Africa by the Leakey family, primarily Mary Leakey, but also her husband Louis and their son, Richard. Mary Leakey organized a typology of Early Pleistocene stone tools, which developed Oldowan tools into three chronological variants, A, B and C.[28] Developed Oldowan B is of particular interest due to changes in morphology that appear to have been driven mostly by the short term availability of a chert resource from 1.65 mya to 1.53 mya. The flaking properties of this new resource resulted in considerably more core reduction and a higher prevalence of flake retouch.[29] Similar tools had already been found in various locations in Europe and Asia for some time, where they were called Chellean and Abbevillian.

The oldest tool sites are in the East African Rift system, on the sediments of ancient streams and lakes. This is consistent with what we surmise of the evolution of man. Genetic studies tell us that the human line (the hominins) possibly diverged from the chimpanzee line (the hominids), and the native territory of the latter is the forests of Central Africa nearby. Fossil chimpanzees have been found in Kenya.

The forests of central and western Africa are a stable environment containing food in abundance for animals such as chimpanzees, and any species living in such an environment would have been under little pressure to evolve further. Eastern Africa is a land of often harsh and unstable environments, and resources are correspondingly scarcer and more difficult to get. Species living in the latter environment would be under greater pressure to evolve and change as needed to survive. A facility for tool-using would contribute to the species' chances of survival.

Even though Olduvai Gorge is the type site, Oldowan tools from here are not the oldest known examples. They occur in Beds I–IV. Bed I, dated 1.85 mya to 1.7 mya, contains Oldowan and fossils of Paranthropus boisei as well as Homo habilis, as does Bed II, 1.7–1.2 mya. H. habilis gives way to Homo erectus at about 1.6 mya but P. boisei goes on. Oldowan continues to Bed IV at 800,000 to 600,000 before present (BP).

South Africa

Abbé Breuil was the first recognized archaeologist to go on record to assert the existence of Oldowan tools. While his description was for "Chello-Abbevillean" tools, and post-dated Leakey's finds at Olduvai Gorge by at least ten years, his descriptions nonetheless represented the scholarly acceptance of this technology as legitimate. These findings were cited as being from the location of the Vaal River, at Vereeniging, and Breuil noted the distinct absence of a significant number of cores, suggesting a "portable culture". At the time, this was considered very significant, as portability supported the conclusion that the Oldowan tool-makers were capable of planning for future needs, by creating the tools in a location which was distant from their use.[30]

Swartkrans

The Swartkrans site is a cave filled with layered fossil-bearing limestone deposits. Oldowan is found in Members (layers) I–III, 1.8–.5 mya, in association with Paranthropus robustus and Homo habilis. The Member I assemblage also includes a shaft of pointed bone polished at the pointed end.

Member I contained a high percentage of primate remains compared to other animal remains, which did not fit the hypothesis that H. habilis or P. robustus lived in the cave. C. K. Brain conducted a more detailed study and discovered the cave had been the abode of leopards, who preyed on the hominins.[31]

Sterkfontein

Another site of limestone caves is Sterkfontein, found in South Africa. This site contains a large number of not only Oldowan tools, but also early Acheulean technology. [32]

Europe

Georgia

In 1999 and 2002, two Homo erectus skulls (H. georgicus) were discovered at Dmanisi in southern Georgia. The archaeological layer in which the human remains, hundreds of Oldowan stone tools, and numerous animal bones were unearthed is dated approximately 1.6-1.8 million years ago. The site yields the earliest unequivocal evidence for presence of early humans outside the African continent.[33]

Bulgaria

At Kozarnika, in the ground layers, dated to 1.4-1.6 Ma, archaeologists have discovered a human molar tooth, lower palaeolithic assemblages that belong to a core-and-flake non-Acheulian industry and incised bones that may be the earliest example of human symbolic behaviour.

Russia

Ainikab-1 and Muhkay-2 (North Caucasus, Daghestan) are the extraordinary sites in relation to date and the culture. Geological and geomorphological data, palynological studies and paleomagnetic testing unequivocally point to Early Pleistocene (Eopleistocene), indicating the age of the sites as being within the range of 1.8 – 1.2 Ma.[34][35]

Spain

Oldowan tools have been found at the following sites: Fuente Nueva 3, Barranco del Leon, Sima del Elefante, Atapuerca TD 6.

France

Oldowan tools have been found at: Lézignan-la-Cèbe, 1.5 mya; Abbeville, 1–.5 mya; Vallonet cave, French Riviera; Soleihac, open-air site in Massif Central. Oldowan tools have also been found at Tautavel in the foothills of the Pyrenees. These were discovered by Henry de Lumbley alongside human remains (cranium). The tools are of limestone and quartz.

Elsewhere

Oldowan tools have been found in Italy at the Monte Poggiolo open air site dated to approximately 850 kya, making them the oldest evidence of human habitation in Italy. In Germany tools have been found in river gravels at Kärlich dating from 300 kya. In the Czech Republic tools have been found in ancient lake deposits at Przeletice and a cave site at Stranska Skala, dated no later than 500 kya. In Hungary tools have been found at a spring site at Vértesszőlős dating from 500 kya.

Asia

Oldowan tools have been found at sites in South Asia and Southwest Asia. In November 2008 tens of sites of Oldowan tools industry were found on the island of Socotra (Yemen).[36][37][38]

In Pakistan tools have been found dating from 1.9 mya at Riwat. In Iran tools have been found dating from the Late Pliocene or Early Pleistocene at Kashafrud. In Israel tools have been found dating from 1.4 mya at el 'Ubeidiya.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Clark, J. G. D. (1969). World prehistory: a new outline. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Clark, J.; de Heinzelin, J.; Schick, K.; Hart, W.; White, T.; WoldeGabriel, G.; Walter, R.; Suwa, G.; Asfaw, B.; Vrba, E.; et al. (1994). "African Homo erectus: Old radiometric ages and young Oldowan assemblages in the middle Awash Valley, Ethiopia". Science. 264 (5167): 1907–1909. doi:10.1126/science.8009220. PMID 8009220.

- ↑ Leakey, Mary (1971). A Summary and Discussion of the Archaeological Evidence from Bed I and Bed II, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Human Origins. pp. 431–460.

- ↑ Isaac, G. Ll., Harris, J. W. K. & Marshall, F. 1981. "Small is informative: the application of the study of mini-sites and least effort criteria in the interpretation of the Early Pleistocene archaeological record at Koobi Fora, Kenya." in "Inter-nacional de Ciencias Prehistoricas Y Protohistoricas", Mexico City. Mexico, pp. 101–119.

- ↑ Napier, John. 1960. "Fossil Hand Bones from Olduvai Gorge." in Nature", December 17th edition.

- 1 2 De Heinzelin, J; Clark, JD; White, T; Hart, W; Renne, P; Woldegabriel, G; Beyene, Y; Vrba, E (1999). "Environment and behavior of 2.5-million-year-old Bouri hominids". Science. 284 (5414): 625–9. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.625. PMID 10213682.

- ↑ Richards, M.P. (December 2002). "A brief review of the archaeological evidence for Palaeolithic and Neolithic subsistence". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 56 (12): 1270–1278. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601646. PMID 12494313 .

- ↑ Semaw, S.; Rogers, M. J.; Quade, J.; Renne, P. R.; Butler, R. F.; Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Stout, D.; Hart, W. S.; Pickering, T.; et al. (2003). "2.6-Million-year-old stone tools and associated bones from OGS-6 and OGS-7, Gona, Afar, Ethiopia". Journal of Human Evolution. 45 (2): 169–177. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(03)00093-9. PMID 14529651.

- ↑ Whiten, A.; Goodall, J.; McGrew, W. C.; Nishida, T.; Reynolds, V.; Sugiyama, Y.; Tutin, C. E. G.; Wrangham, R. W.; Boesch, C.; et al. (1999). "Cultures in Chimpanzees". Nature. 399 (6737): 682–685. doi:10.1038/21415. PMID 10385119.

- ↑ Schaik, CP; Ancrenaz, M.; Borgen, G.; Galdikas, B.; Knott, C. D.; Singleton, I.; Suzuki, A.; Utami, S. S.; Merril, M.; et al. (2003). "Orangutan cultures and the evolution of material culture". Science. 299 (5603): 102–105. doi:10.1126/science.1078004. PMID 12511649.

- ↑ Ko, Kwang Hyun. "Origins of human intelligence: The chain of tool-making and brain evolution" (PDF). Anthropological Notebooks. 22 (1): 5–22.

- ↑ Panger, M. A.; Brooks, A. S.; Richmond, B. G.; Wood, B. (2002). "Older than the Oldowan? Rethinking the emergence of hominin tool use". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 11 (6): 235–245. doi:10.1002/evan.10094.

- ↑ Swisher, C. C.; Curtis, G. H.; Jacob, T.; Getty, A. G.; Suprijo, A.; Widiasmoro (1994). "Age of the earliest known hominids in Java, Indonesia". Science. 263 (5150): 1118–1121. doi:10.1126/science.8108729. PMID 8108729.

- ↑ Zhu, R. X.; Potts, R. R.; Xie, F.; Hoffman, K. A.; Shi, C. D.; Pan, Y. X.; Wang, H. Q.; Shi, R. P.; Wang, Y. C.; et al. (2004). "New evidence on the earliest human presence at high northern latitudes in northeast Asia". Nature. 431 (7008): 559–562. doi:10.1038/nature02829. PMID 15457258.

- ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/07/0703_020704_georgianskull.html

- ↑ Oms, O.; Pares, J. M.; Martinez-Navarro, B.; Agusti, J.; Toro, I.; Martinez-Fernandez, G.; Turq, A. (2000). "Early human occupation of Western Europe: Paleomagnetic dates for two paleolithic sites in Spain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (19): 10666–10670. doi:10.1073/pnas.180319797.

- ↑ Pares, J. M.; Perez-Gonzalez, A.; Rosas, A.; Benito, A.; Carbonell, E.; Huguet, R.; Huguet, R (2006). "Matuyama-age lithic tools from the Sima del Elefante site, Atapuerca (northern Spain)". Journal of Human Evolution. 50 (2): 163–169. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.08.011. PMID 16249015.

- ↑ Ambrose, S. H. (2001). "Paleolithic technology and human evolution". Science. 291 (5509): 1748–1753. doi:10.1126/science.1059487. PMID 11249821.

- ↑ There is a good online summary of Mary's classification on Effland's site for Anthropology ASB22 at Mesa Community College in Arizona, apparently written by Effland.

- ↑ Susman, R.L, "Who made the Oldowan Stone Tools?" 1991

- ↑ Carvalho, S., Cunha, E., Sousa, C., Matsuzawa, T. 2008.Chaînes opératoire and resource-exploitation strategies in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) nut cracking. Journal of Archaeological Science.

- ↑ Klein, Richard G. (22 April 2009). The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins (Third ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-0-226-02752-4. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Semaw, Sileshi (2000). "The World's Oldest Stone Artefacts from Gona, Ethiopia: Their Implications for Understanding Stone Technology and Patterns of Human Evolution Between 2·6–1·5 Million Years Ago". Journal of Archaeological Science. 27: 1197–1214. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0592.

- ↑ de la Torre, Ignacio; deBeaune, S.; Davidson, I.; Gowlett, J.; Hovers, E.; Kimura, Y.; Mercader, J.; de la Torre, I. (2004). "Omo Revisited: Evaluating the Technological Skills of Pliocene Hominids". Current Anthropology. 45 (4): 439–465. doi:10.1086/422079.

- ↑ Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 9. ISBN 0-395-13592-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Bishop, L. C.; Plummer, T. W.; Ferraro, J. V.; Braun, D.; Ditchfield, P. W.; Hertel, F.; Kingston, J. D.; Hicks, J.; Potts, R. (Mar–Jun 2006). "Recent Research into Oldowan Hominin Activities at Kanjera South, Western Kenya". The African Archaeological Review. 23 (1/2): 31–40. doi:10.1007/s10437-006-9006-1. JSTOR 25470615.

- ↑ Thomas Plummer (2005). Stahl, Ann Brower, ed. African Archaeology. Malden, MA: Blackwee Publishing Ltd. pp. 55–92.

- ↑ Barham & Mitchell, Lawernce & Peter (2008). The First Africans. Cambridge World Archaeology. pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Kimura, Yuki (2002). "Examining time trends in the Oldowan technology at Beds I and II, Olduvai Gorge". Journal of Human Evolution. 43: 291–321. doi:10.1006/jhev.2002.0576.

- ↑ Breuil, Abbé Henri; "A Preliminary Survey of Work in South Africa"; The South African Archaeological Bulletin; v.1, no.1, Dec. 1945, pp. 5-7

- ↑ Many scientists had drawn the erroneous conclusion that Homo habilis was the predator responsible for these remains, using Oldowan tools. The higher percentage of primate bones was interpreted as a kind of cannibalism, feeding the imagination of Raymond Dart. Brain examined the bones and concluded that the marks resulting from stripping and chewing the bones were made by a leopard.

- ↑ Petraglia, edited by Michael D.; Korisettar, Ravi (1998). Early human behaviour in global context the rise and diversity of the Lower Palaeolithic record. London: Routledge. ISBN 0203203275.

- ↑ Vekua, A.; Lordkipanidze, D.; Rightmire, G. P.; Agusti, J.; Ferring, R.; Maisuradze, G.; et al. (2002). "A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia". Science. 297 (5578): 85–9. doi:10.1126/science.1072953. PMID 12098694.

- ↑ Taymazov A.I. (2011) Main characteristics of the industry at Ainikab I multilayer Early Paleolithic site (based on the data from the 2005–2009 investigations). Russian Archaeology, #1, 1-9.

- ↑ Chepalyga A.L., Amirkhanov Kh.A., Trubikhin V.M., Sadchikova T.A., Pirogov A.N., Taimazov A.I. Geoarchaeology of the earliest paleolithic sites (Oldowan) in the North Caucasus and the East (2012). International Conference GEOMORPHIC PROCESSES AND GEOARCHAEOLOGY: From Landscape Archaeology to Archaeotourism. Moscow-Smolensk, 20–24 August.

- ↑ Амирханов Х.А., Жуков В.А., Наумкин В.В., Седов А.В. "Эпоха олдована открыта на острове Сокотра"."Природа", № 7/2009

- ↑ http://www.ihae.ru/konfer/simpozium.htm

- ↑ Zhukov, Valery A. (2014) The Results of Research of the Stone Age Sites in the Island of Socotra (Yemen) in 2008-2012. - Moscow: Triada Ltd. 2014, pps 114, ill. 134 (in Russian)ISBN 978-5-89282-591-7

Sources

- Braidwood, Robert J., Prehistoric Men, many editions.

- Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Pickering, T. R.; Semaw, S.; Rogers, M. J. (2005). "Cutmarked bones from Pliocene archaeological sites at Gona, Afar, Ethiopia: Implications for the function of the world's oldest stone tools". Journal of Human Evolution. 48 (2): 109–121. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.09.004. PMID 15701526.

- Edey, Maitland A., The Missing Link, Time-Life Books, 1972.

- Schick, Kathy D.; Toth, Nicholas, Making Silent Stones Speak', Simon & Schuster, 1993, ISBN 0-671-69371-9

- Semaw, Sileshi (2000). "The worlds oldest stone artefacts from Gona Ethiopia: Their implications for understanding stone technology and patterns of human evolution between 2.6–1.5 million years ago". Journal of Archaeological Science. 27 (12): 1197–1214. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0592.

- Isaac, Glynn and Harris, JWK The Scatter between the Patches 1975

- Isaac, Glynn (1978). "The Food Sharing Behavior of Protohuman Hominids". Scientific American. 238 (4): 90–108. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0478-90. PMID 418504.

- Binford, Lewis (1987) Searching for Camps and Missing the Evidence: Another Look at the Lower Paleolithic

- Toth, Nicholas (1985) The Oldowan reassessed: a close look at early stone artifacts Journal of Archaeological Science

- Susman, Randall L, Journal of Anthropological Research, Vol. 47, No. 2, A Quarter Century of Paleoanthropology: Views from the U.S.A. (Summer, 1991), pp. 129–151

External links

- Oldowan Pebble Tools of Europe

- Oldowan Pebble Tools of Africa

- Oldowan Flake Tool

- Stone Age Hand-axes at the Wayback Machine (archived February 4, 2007)

- Early Palaeolithic

- Stone Age Reference Collection

- Microwear polishes on early stone tools from Koobi Fora, Kenya, article in Nature 293, 464–465 (8 October 1981). The summary and the references are displayed at no charge at the Nature site.

- Geoarchaeology of the earliest paleolithic sites (Oldowan) in the north Caucasus and the East Europe

- An Ape's View of the Oldowan at the Wayback Machine (archived May 21, 2008), T. Wynn and W.C. McGrew, Man 24:383–398; 1989.

- Flaked Stones and Old Bones: Biological and Cultural Evolution at the Dawn of Technology, Thomas Plummer, Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 47:118–164 (2004).

Coordinates: 36°12′03″N 5°39′16″E / 36.2009°N 5.6544°E

| Neogene Period | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Miocene | Pliocene | ||

| Aquitanian | Burdigalian Langhian | Serravallian Tortonian | Messinian |

Zanclean | Piacenzian | ||