Rojava conflict

| Rojava conflict | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Syrian Civil War | |

PYD supporters at a funeral | |

| Date | 19 July 2012 – present (4 years, 4 months, 2 weeks and 3 days) |

| Location | Al-Hasakah Governorate, Ar-Raqqah Governorate, and Aleppo Governorate, Syria (de facto Jazira Canton, Kobanî Canton, Shahba Canton and Afrin Canton, Rojava) |

| Goals | |

| Methods | |

| Status |

Ongoing

|

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 17,215–17,241[1][2][3][4][5] |

The Rojava conflict, also known as the Rojava revolution, is a political upheaval, social revolution[6] and military conflict taking place in Northern Syria, known as Rojava. During the Syrian Civil War, a coalition of Arab, Kurdish, Syriac and some Turkmen groups have sought to establish the Constitution of Rojava inside the de facto autonomous region, while military wings and allied militias have fought to maintain control of the region. The revolution has been characterized by the prominent role played by women both on the battlefield and within the newly formed political system, as well as the implementation of democratic confederalism, a form of grassroots democracy based on local assemblies.

Background

The area is strategically important, because it contains a large percentage of Syria's oil supplies.[7]

State discrimination

Repression of the Kurds and other ethnic minorities has gone on since the creation of the French Mandate of Syria after the Sykes-Picot Agreement.[8] The Syrian government (officially known as the Syrian Arab Republic) never officially acknowledged the existence of the Kurds[8] and in 1962 120,000 Syrian Kurds were stripped of their citizenship, leaving them stateless.[9] The Kurdish language and culture have also been suppressed. The government attempted to resolve these issues in 2011 by granting all Kurds citizenship, but only an estimated 6,000 out of 150,000 stateless Kurds have been given nationality and most discriminatory regulations, including the ban on teaching Kurdish, are still on the books.[10] Due to the Syrian Civil War, which began in 2011, the government is no longer in a position to enforce these laws.

Qamishli uprising

In 2004, riots broke out against the government in the northeastern city of Qamishli. During a soccer match between a local Kurdish team and a visiting Arab team from Deir ez-Zor, some Arab fans brandished portraits of Saddam Hussein (who slaughtered tens of thousands of Kurds in Southern Kurdistan during the genocidal Al-Anfal campaign in the 1980s). Tensions quickly escalated into open protests, with Kurds raising their flag and taking to the streets to demand cultural and political rights. Security forces fired into the crowd, killing six Kurds, including three children. Protesters went on to burn down the Ba'ath Party's local office. At least 30 and as many as 100 Kurds were killed by the government before the protests were quelled. Thousands of Kurds fled to Iraq afterwards, where a refugee camp was established. Occasional clashes between Kurdish protesters and government forces occurred in the following years.[11][12]

Origins

Syrian Civil War

In 2011, the Arab Spring spread to Syria. Similar to the beginning of the Tunisian revolution, Syrian citizen Hasan Ali Akleh soaked himself in gasoline and set himself on fire in the northern city of Al-Hasakah. This inspired activists to call for a "Day of Rage", which ended up being sparsely attended, mostly because of fear of repression from the Syrian government. Days later, however, protests again took place, this time in response to the police beating of a shopkeeper.[13]

Smaller protests continued, but it was on 7 March 2011, when thirteen political prisoners went on hunger strike, that momentum began to grow against the Assad government. Three days later dozens of Syrian Kurds went on hunger strike in solidarity.[14] On 12 March, major protests took place in Al-Qamishli and Al-Hasakah to both protest the Assad government and commemorate Kurdish Martyrs Day.[15]

Protests grew over the months of March and April 2011. The Assad government attempted to appease Kurds by promising to grant citizenship to thousands of Kurds, who until that time had been stripped of any legal status.[16] By the summer, protests had only intensified, as did violent crackdowns by the Syrian government.

In August, a coalition of opposition groups formed the Syrian National Council in hopes of creating a democratic, pluralistic alternative to the Assad government. However, internal fighting and disagreement over politics and inclusion plagued the group from its early beginnings. In the fall of 2011 the popular uprising escalated to an armed conflict. The Free Syrian Army (FSA) began to coalesce and armed insurrection spread largely across the central and southern parts of Syria.

Kurds and government opposition negotiations

The National Movement of Kurdish Parties in Syria, a coalition of Syria's 12 Kurdish parties, boycotted a Syrian opposition summit in Antalya, Turkey on 31 May 2011, stating that "any such meeting held in Turkey can only be a detriment to the Kurds in Syria, because Turkey is against the aspirations of the Kurds."[17]

During the August summit in Istanbul, which led to the creation of the Syrian National Council, only two of the parties in the National Movement of Kurdish Parties in Syria, the Kurdish Union Party and the Kurdish Freedom Party, attended the summit.[18]

Erbil agreement

_Kurdish_Syria.jpg)

Anti-government protests had been ongoing in the Kurdish-inhabited areas of Syria since March 2011, as part of the wider Syrian uprising, but clashes started after the opposition Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Kurdish National Council (KNC) signed a seven-point agreement on 11 June 2012 in Erbil under the auspice of Iraqi Kurdistan president Massoud Barzani. This agreement, however, failed to be implemented and so a new cooperation agreement between the two sides was signed on 12 July which saw the creation of the Kurdish Supreme Committee as a governing body of all Kurdish-controlled territories in Syria.[19][20][21]

YPG claims territory

The People's Protection Units (YPG) entered the conflict by capturing the city of Kobanî on 19 July 2012, followed by the capture of Amuda and Efrîn on 20 July.[22] The cities fell without any major clashes, as Syrian security forces withdrew without any significant resistance.[22] The Syrian Army pulled out to fight elsewhere.[23] The KNC and PYD afterwards formed a joint leadership council to run the captured cities.

The YPG forces continued with their advancement and on 21 July captured Al-Malikiyah (Kurdish: Dêrika Hemko), which is located 10 kilometers from the Turkish border.[24] The rebels at the time also intended to capture Qamishli, the largest Syrian city with a Kurdish majority.[25] On the same day, the Syrian government attacked a patrol of Kurdish YPG members and wounded one fighter.[26] The next day it was reported that Kurdish forces were still fighting for Al-Malikiyah, where one young Kurdish activist was killed after government security forces opened fire on protesters. The YPG also took control over the towns of Ra's al-'Ayn (Kurdish: Serê Kaniyê) and Al-Darbasiyah (Kurdish: Dirbêsî), after the security and political units withdrew from these areas, following an ultimatum issued by the Kurds. On the same day, clashes erupted in Qamishli between YPG and government forces in which one Kurdish fighter was killed and two were wounded along with one government official.[27]

The ease with which Kurdish forces captured the towns and the government troops pulled back was speculated to be due to the government reaching an agreement with the Kurds so military forces from the area could be freed up to engage opposition forces in the rest of the country.[28] On 24 July, the PYD announced that Syrian security forces withdrew from the small Kurdish city of 16,000 of Al-Ma'bada (Kurdish: Girkê Legê), located between Al-Malikiyah and the Turkish borders. The YPG forces afterwards took control of all government institutions.[29]

Popular protest continued in Rojava through 2011 and into the spring of 2012 though most Kurds and other Northern Syrians did not join the FSA because of disagreements over Kurdish representation in a future Syria.[30]

Self-governed Rojava established

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Rojava |

|

Symbols |

|

Legislature |

|

Elections |

|

|

Party alliances

|

|

Self-governing cantons |

On 1 August 2012, Assad forces on the periphery of the country were pulled into the intensifying conflict taking place in Aleppo. During this large withdrawal from the north, the People's Protection Units (YPG), a pro-Kurdish militia that formed after the 2004 al-Qamishli riots[31] took control of at least parts of Qamishlo, Efrin, Amude, Terbaspi and Ayn El Arab with very little conflict or casualties.[32]

On 2 August 2012, the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change announced that most Kurdish dominated cities in Syria, with the exception of Qamishli and Hasaka, were no longer controlled by government forces and were now being governed by Kurdish political parties.[33] In Qamishli, government military and police forces remained in their barracks and administration officials in the city allowed the Kurdish flag to be raised.[34]

It was reported in August that the Kurds in northern controlled Syria had set up local committees and checkpoints to search cars. The border crossing between northeastern Syria and Iraq was no longer occupied by government forces. Kurds stated that they would defend their towns if government or opposition forces attempted to enter them. In some areas of Qamishli, government checkpoints were still active, however, Kurds denied cooperation with the Syrian government and stated that the troops remained in their checkpoints with hopes of avoiding a military confrontation.[35] In the same month, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) successfully bombed the government's intelligence center in the city.[36]

After months of de facto rule, the PYD officially announced its regional autonomy on 9 January 2014. Elections were held, popular assemblies established and the Constitution of Rojava was approved. Since then, residents have been organizing local assemblies, re-opening schools, establishing community centers and pushing back ISIS to gain control of further territory. They see their model of grassroots democracy as a model that can be implemented throughout the country in a post-Assad Syria.

Social revolution

After declaring autonomy, grassroots organizers, politicians and other community members have radically changed the social and political make up of the area. The extreme laws restricting independent political organizing, women's freedom, religious and cultural expression and the discriminatory policies carried out by the Assad government have been abolished. In its place, a constitution guaranteeing the cultural, religious and political freedom of all people has been established. The constitution also explicitly states the equal rights and freedom of women and also "mandates public institutions to work towards the elimination of gender discrimination."[6]

The political and social changes taking place in Rojava have in large part been inspired by the libertarian socialist politics of Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan.[6]

Cooperative economy

The Rojava economy is a blend of private companies, the autonomous administration and worker cooperatives. The majority of the economy goes towards supporting forces fighting the Assad government, Islamist forces and now on occasion Turkish forces. Since the revolution, efforts have been made to transition the economy to one of self-sufficiency based on worker and producer cooperatives. This transition faces major obstacles of ongoing conflict and an embargo from all surrounding areas.

- Embargo

Rojava is under a severe embargo from all neighboring countries: Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and the various forces controlling nearby areas of Syria. This has forced people to rely almost exclusively on diesel-run generators for electricity. Additionally, strong emphasis is being placed on businesses that can bring about self-sufficiency to the region.

- Semi-autonomous administration

There are no required taxes in Rojava. Instead the administration funds itself through the sale of oil and border commerce (which is technically clandestine because of the embargo). There are partnerships that have been created between private companies and the administration. The administration also funds the school system and distributes bread to all citizens at a below-market rate.[37]

- Community economy

The Movement for a Democratic Society Economic Committee has been helping businesses move towards a "community economy" based on worker cooperatives and self-sufficiency.[37]

Cooperatives first formed in the agricultural and infrastructure sectors. In the Jazira Canton there are 18 agricultural cooperatives, 12 general co-ops and 6 women run co-ops.

Other cooperatives include:

- Bottled mineral water

- Construction

- Factories

- Fuel stations

- Generators

- Livestock

- Oils

- Pistachio and roasted seeds

- Public markets

Additionally there are several agricultural communes with families collectively working the land.[38]

Direct democracy

The Rojava Cantons are governed through a combination of district and civil councils. District councils consist of 300 members as well as two elected co-presidents- one man and one woman. District councils decide and carry out administrative and economic duties such as garbage collection, land distribution and cooperative enterprises.[39] Civil councils exist to promote the social and political rights within the community.

Ethnic minority rights

Closely related to religious freedom and the protection of religious minorities is the protection of ethnic minorities. Kurds now have the right to study their language freely as do Assyrians. For the first time, a Kurdish curriculum has been introduced to the public school system.

Residents are also now free to express their culture freely. Culture and music centers have formed, hosting dance classes, music lessons and choir practice.[40]

In some areas, there is an ethnic minority quota in addition to the gender quota for councils.[41]

Restorative Justice

The criminal justice is undergoing significant reforms, moving away from a punitive approach under the Assad government to one based on the principles of restorative justice. Reconciliation Committees have replaced the Syrian government court system in several cities.[42] Committees are representative of the ethnic diversity in their respective area. For example, the committee in Tal Abyad has members from the Arabic, Kurdish, Turkmen and Armenian communities.[43]

Women's rights

- Repression of women Under Syrian government

Under the Assad government, women face extreme forms of repression, violence and discrimination. Sexual assault and domestic violence occur at very high rates, with little protection under the law or through the courts. Conservative social norms restricts women's movement and participation in public life. Economic opportunities had begun to improve to a certain degree, though since the civil war broke out the economy has collapsed in many areas.[44]

- Jineology and the Rojava revolution

Feminism, specifically Jineology (the science of women), is central to the social revolution taking place in Rojava. Much of the focus of the revolution has been addressing the extreme levels of violence which women in the area have endured as well as increasing women leadership in all political institutions.

All YPG and YPJ fighters and Asayish forces study Jineology as part of their training and is also taught in community centers.[45]

- Women's houses

In every town and village under YPG control, a women's house is established. These are community centers run by women, providing services to survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault and other forms of harm. These services include counseling, family mediation, legal support, and coordinating safe houses for women and children.[46] Classes on economic independence and social empowerment programs are also held at women's houses.[47]

- Banning of child marriages and honor killings

Efforts are also being made to reduce cases of underage marriage, polygamy and honor killings both socially as well as through legislation forbidding these practices.[48]

- Women's leadership

A key component of the direct democracy model being enacted in Rojava is co-leadership. Every major position in both civil and military institutions are led by a man and a woman. This is to ensure gender balance in power and decision-making, as well as a general level of accountability for the position as it requires two people to reach agreement on decisions made.

A 40% gender quota required of all councils in order for a vote to take place.[46]

Religious freedom

Christian Assyrians, Muslim Kurds and others have worked together both in fighting government forces and Islamist groups as well as in managing political affairs. The right to religious expression is also safeguarded in the constitution. Because of this as well as the extreme hostility towards religious minorities in Islamist controlled areas it has led to a large migration of religious minorities to Rojava.[49]

For the first time in Syrian history, civil marriage is being allowed and promoted. This is a significant move towards increased tolerance between people of different religious backgrounds.[50]

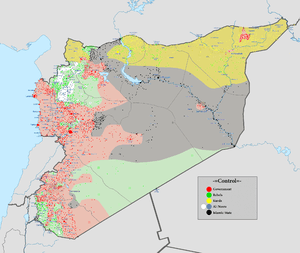

Combatants

There are four major forces involved in the Rojava revolution. The People's Protection Units are working with the PYD and other political parties to establish self-rule in Rojava. Syrian government forces still maintain rule in some areas of Rojava under the leadership of the Assad regime. A collection of Islamic forces, the largest being ISIS are fighting to rule the region by Sharia law. Finally, there are several militias under the general banner of the Free Syrian Army whose intentions and alliances have differed and shifted over time. At the moment, most FSA fighters are working with the YPG against Islamist forces and the Syrian government.

YPG-Syrian government relations

While conflict between the YPG and Syrian government has not been as active as fighting against Islamist forces, there have been several conflicts between the two forces. Territory once controlled by the Syrian government in Qamishli and al-Hasakah have both been lost to YPG forces. At the end of April 2016, clashes have erupted between government forces and Kurdish fighters for the control of the city.[51]

As of the beginning of August 2016, YPG fighters controlled two-thirds of the northeastern city of al-Hasakah, while pro-government militia controlled the remainder. On 17 August 2016, heavy clashes broke out between Kurdish fighters and the pro-government militias, resulting in the deaths of four civilians, four Kurdish fighters, and three government loyalists. On 18 August, Syrian government aircraft bombed Kurdish positions in Hasakah, including three Kurdish checkpoints and three Kurdish bases. Syrian Kurds had recently demanded that the pro-government National Defense Forces militia disband in al-Hasakah. A government source told the AFP that the air strikes were "a message to the Kurds that they should stop this sort of demand that constitutes an affront to national sovereignty."[52] Another possible factor behind the fighting may have been the recent thaw in Turkish-Russian relations that began in July 2016; Russia, a key ally of the Syrian government, had previously been supporting Syrian Kurdish forces as a means to apply pressure to Turkey. After the recent setbacks suffered by ISIS in Syria and Iraq and improvements in the Turkish-Russian relationship, it is possible that Russia and its allies began to view a strong YPG as increasingly less useful.[53]

In response to the attacks by the Syrian aircraft on Kurdish positions near al-Hasakah, the United States scrambled planes over the city in order to deter further attacks.[54]

By 22 August, Syrian government troops, Hezbollah fighters, and members of the Iranian paramilitary Basij militia had become involved in the fighting against Kurdish forces in al-Hasakah.[55]

YPG and FSA relations

The relationship between the People's Protection Units (YPG) and the Free Syrian Army (FSA) has been one of tentative cooperation. Both are opposed to the Syrian government and ISIS, however clashes have taken place. Recently, the two forces have been working together to battle ISIS under the name of Euphrates Volcano.

YPG-Islamist conflict

On 4 May 2013, YPG forces and Jihadist militants, including Al Nusra, clashed in areas close to the cities of Hasaka and Ras al-Ain.[56] Reports seemed to suggest that FSA forces were arming Arab tribes in the town of Tell Tamer; encouraging them to confront Kurdish groups. Despite hit and run attacks which led to the deaths of several YPG members as well as civilians, YPG forces reportedly held off the armed groups.[57]

.png)

YPG forces have clashed heavily with Islamist forces. Most notable have been the Siege of Kobani and more recently the Al-Hasakah Offensive and Tell Abyad Offensive.

Internal conflict

On 28 December 2012, Syrian government forces opened fire on pro-FSA demonstrators in al-Hasakah city, killing and wounding several individuals. Arab tribes in the area attacked YPG positions in the city in reprisal, accusing the Kurdish fighters of collaborating with the government. Clashes broke out, and three Arabs were killed, though it was not clear whether they were killed by YPG forces or nearby government troops.[58] Demonstrations were organised by various Kurdish groups throughout Western Kurdistan in late December as well. PYD supporters drove vehicles at low speeds through a KNC demonstration in Qamishli, raising tensions between the two groups.[59]

From 2 to 4 January, PYD-led demonstrators staged protests in the al-Antariyah neighbourhood of Qamishli, demanding "freedom and democracy" for both Kurds and Syrians. Many activists camped out on site. On 4 January, approximately 10,000 people were participating in the rallies, which also included smaller numbers of supporters of other Kurdish parties,[60] such as the KNC, which staged a rally in the Munir Habib neighbourhood. PYD organisers had planned for 100,000 people to participate, but such support did not materialise. The demonstrations were concurrent with rallies conducted across the country by the Arab opposition, though Kurdish parties did not use the same slogans as the Arabs, and also did not the same slogans amongst their own parties. Kurds also demonstrated in several other towns, but not across the entire Kurdish region.[61]

Meanwhile, several armed incidents occurred between the dominant PYD-YPG and other Kurdish parties in the region, particularly the Kurdish Union ("Yekîtî") Party, part of a Kurdish political coalition called the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union formed on 15 December 2012, which excludes the PYD.[62] On 3 January, PYD gunmen staged a drive-by shooting on a Yekîtî office in Qamishli. Armed Yekîtî members returned fire, injuring one PYD member.[63] The same day, armed clashes broke out between YPG fighters and members of the newly formed Jiwan Qatna Battalion of Yekîtî in ad-Darbasiyah. Four Yekîtî members were abducted by the YPG, who accused them of being affiliated with Islamist groups, though Yekîtî activists alleged that the PYD wanted to prevent other Kurdish groups from arming themselves. Following demonstrations in the town demanding their release and an intervention by the KNC, the four men were released by the end of the day.[64] On 11 January, YPG forces raided an empty Yekîtî training ground near Ali Faru which had been built in early January, tearing down both the Kurdish and FSA flags that had been flying at the base. Though PYD members defended the raid by saying that the flags could have attracted government airstrikes, Yekîtî condemned the action.[65]

On 31 January, Kamal Mustafa Hanan, editor-in-chief of Newroz (a Kurdish-language journal) and a former Yekîtî politician, was fatally shot in the Ashrafiyah district of Aleppo. It was not clear if he was the victim of a stray bullet or of a politically motivated assassination. Yekîtî organised a funeral procession in the town of Afrin in the Kurdish-held northwest corner of Aleppo Province on 1 February, which members of both the PYD and KNC attended.[66] Also on 1 February, Kurds staged demonstrations in several towns and villages across West Kurdistan concurrent with opposition demonstrations elsewhere in the country. The demonstrations were organised by various Kurdish groups, including the PYD and KNC. Demonstrators from the KNC demanded an end to fighting in Ras al-Ayn and the withdrawal of armed groups from the town, while PYD demonstrators stressed solidarity with their YPG units and the Kurdish Supreme Council.[67]

From 2 to 5 February, YPG forces blockaded the village of Kahf al-Assad (Kurdish: Banê Şikeftê), inhabited by members of the Kurdish Kherikan tribe, after being fired upon by unknown gunmen in the village. YPG checkpoints were also established around other Kherikan villages. The Kherikan are traditionally supporters of the Massoud Barzani government of Iraqi Kurdistan, and as oppose the PYD. The blockade was the third time in two years that hostilities had broken out between the PYD/YPG and locals from Kahf al-Assad.[68]

On 7 February, YPG members kidnapped three members of the opposition Azadî party in Ayn al-Arab.[69]

On 22 February, Osman Baydemir, mayor of the city of Diyarbakır in Turkey, announced the initiation of a one-month humanitarian aid programme in which his city—along with the surrounding districts of Bağlar, Yenişehir, Kayapınar, and Sur—would provide food assistance to Kurdish areas in Syria affected by the war, which had received little of the humanitarian aid that other regions of Syria had received.[70]

On 11 April 2016, PYD supporters attacked the offices of the Kurdish National Council and the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria in Derbessiye and Qamishli.[71] The head of the Kurdish National Council told Turkey's TRT World channel the PYD's oppressive attitude in Syria is forcing Kurds to leave the region.[72]

YPG-Turkey conflict

Turkey has long observed the PYD as a Syrian extension of the Turkish pro-Kurdish network PKK, and has therefore taken a hardline against the group, insisting that they will not allow a Kurdish state to form along their southern border with Syria. Following major YPG successes in 2015, notably the capture of Tell Abyad, Turkey began indiscriminately targeting YPG forces in northern Syria.[5]

In 2016, following the capture of Tishrin Dam, allowing the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to cross the River Euphrates, a proclaimed 'red line' by Turkey. Turkish forces bombed the Kurdish YPG headquarters in Tell Abyad, destroying three armoured vehicles and injuring two Kurdish fighters.[73] The following day, 21 January 2016, Turkish troops crossed the border with Syria and entered the ISIS-controlled Syrian border town of Jarabulus which the YPG had been planning on capturing as part of an offensive to unite their areas of control into one continuous banner of territory.

Since 16 February 2016, Turkish forces have been shelling Kurdish forces in the Afrin Canton after the SDF took initiative from an SAA offensive and captured rebel-held areas of the Azaz District, notably Tell Rifaat and Menagh Airbase. The Turks have vowed not to allow the Kurds to capture the key border town of Azaz. As a result 25 Kurdish militants have been killed and 197 injured from Turkish artillery fire.[74]

Kurdish-led forces in northern Syria said Turkish airstrikes hit their bases in Amarneh village near Jarablus on 27 August 2016, after Turkish artillery shelled the positions the day before.[75]

The Syrian Observatory reported on 27 August 2016, about exchange of gunfire between YPG and the Turkish forces in the countryside north of Hasakah. It is unclear if Turkish forces were on Syrian territory or had fired across the border.[76]

According to a 16 November 2016 report by Voice of America, "A Syrian Kurdish militia withdrew its forces Wednesday from the strategic northern Syrian town of Manbij, three months after helping to free it from Islamic State control."[77] Yet conflicting reports have been reported that instead of YPG militia retreating to the east of the Euphrates as promised by the U.S. administration, the group has been advancing towards the northern Syrian town of al-Bab, a key point to link its cantons against Turkey's warnings.[78]

On 22 November 2016, the Daily Sabah reported, "The United States is not backing PKK's Syrian offshoot, the People's Protection Units (YPG)'s offensive to capture al-Bab, a Daesh stronghold in Syria, the Pentagon said on Monday."[79] The US-led coalition also did not back the Turkey-led operation on al-Bab, stating that it will be an independent Turkish operation.[80]

See also

- Cities and towns during the Syrian Civil War

- Democratic Confederalism

- International Freedom Battalion

- Rojava

- Syrian Democratic Forces

- Syrian Kurdish–Islamist conflict (2013–present)

- Kurdish–Turkish conflict (2015–present)

References

- ↑ 122–148 in Ras al-Ayn , 30 in Aleppo Archived 14 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "YPG release balance sheet of war for 2013". Firatnews. 23 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ↑ "YPG releases balance-sheet of 2014: Nearly 5,000 ISIS members killed". BestaNûçe Bestanuce.com. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "More than 5500 ISIS militants killed in clashes with Syrian Kurds in 2015 - ARA News". ARA News.

- 1 2 http://ypgrojava.com/en/2016/01/01/balance-of-the-war-against-hostile-groups-in-rojava-northern-syria-year-2015/

- 1 2 3 Enzinna, Wes. "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". NY Times. NY Times. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ↑ "CIA – The World Factbook". CIA. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- 1 2 Gorgas, Jordi Tejel. "Les territoires de marge de la Syrie mandataire : le mouvement autonomiste de la Haute Jazîra, paradoxes et ambiguïtés d'une intégration « nationale » inachevée (1936-1939)".

- ↑ "The Silenced Kurds". Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Minority Kurds struggle for recognition in Syrian revolt". The Daily Star Lebanon. 31 March 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ Brandon, James (21 February 2007). "The PKK and Syria's Kurds". Terrorism Monitor. Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation. 5 (3). Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ↑ Isseroff, Ami (24 March 2004). "Kurdish agony – the forgotten massacre of Qamishlo". MideastWeb. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ↑ Iddon, Paul. "A recap of the Syrian crisis to date". Digital Journal. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ "Jailed Kurds on Syria hunger strike: rights group". Agence France-Presse. 10 March 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ Khatib, Lina; Lust, Ellen (1 May 2014). Taking to the Streets: The Transformation of Arab Activism. JHU Press. p. 161 of 368. ISBN 1421413132. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "Many arrested in Syria after protests". Al Jazeera. 2 April 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ↑ Furuhashi, Yoshie (29 May 2011). "Syrian Kurdish Parties Boycott Syrian Opposition Conference in Antalya, Turkey". Monthly Review. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ "Most Syrian Kurdish Parties Boycott Opposition Gathering". Rudaw. 29 August 2011. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ "Syrian Kurds Try to Maintain Unity". Rudaw. 17 July 2012. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Syria: Massive protests in Qamishli, Homs". CNTV. 19 May 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Syrian Kurdish Official: Now Kurds are in Charge of their Fate". Rudaw. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- 1 2 "More Kurdish Cities Liberated As Syrian Army Withdraws from Area". Rudaw. 20 July 2012. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "After quiet revolt, power struggle looms for Syria's Kurds". Mobile.reuters.com. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ↑ "City of Derik taken by Kurds in Northeast Syria". Firat news. 21 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Ban: Syrian regime 'failed to protect civilians'". CNN. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Clashes between Kurds and Syrian army in the Kurdish city of Qamişlo, Western Kurdistan". Ekurd.net. 21 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Armed Kurds Surround Syrian Security Forces in Qamishli". Rudaw. 22 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Fighting in Syria indicates Bashar Assad's end isn't imminent". Charlotteobserver.com. 23 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Girke Lege Becomes Sixth Kurdish City Liberated in Syria". Rudaw. 24 July 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "After Damascus attack, Syria vows to strike with 'iron fist'". CNN. 6 January 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ↑ "Meet the YPG". Vice News. Vice News. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Davies, Wyre (27 July 2012). "Crisis in Syria emboldens country's Kurds". BBC News. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ "PYD Press Release: A call for support and protection of the peaceful establishment, the self-governed Rojava region | هيئة التنسيق الوطنية لقوى التغيير الديمقراطي". Syrianncb.org. 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ "Syria – News". Peter Clifford Online. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ "Kurds take control in Syria's northeast". Syria Live Blog. Al Jazeera English. 12 August 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Explosion at intelligence center in Qamishli, Syrian Kurdistan". Ekurd.net. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- 1 2 "Rojava's Threefold Economy". Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ "The Experience of Co-operative Societies in Rojava". Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Tax, Meredith. "The Revolution in Rojava". Dissent Magazin. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ "A Kurdish Spring in Syria". DW. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ "Rojava: only chance for a just peace in the Middle East". March 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ "Reconciliation Committee Solves 1977 cases in Serekaniye". Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ "Reconciliation Committee replaces courts in Girê Spî". Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ "Syrian Arab Republic ftn5". Gender Index. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ Argentieri, Benedetta. "These female Kurdish soldiers wear their femininity with pride".

- 1 2 Owen, Margaret. "Gender and justice in an emerging nation: My impressions of Rojava, Syrian Kurdistan". Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ "Revolution in Rojava transformed the perception of women in the society". Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ "Syrian Kurds give women equal rights, snubbing jihadists". Yahoo News. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ "Joint statement to the academic delegation at Rojava". 15 January 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ↑ "Syria Kurds promote civil marriage". ARA News. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ http://www.voanews.com/media/video/3297343.html

- ↑ "MIDEAST - Syrian regime forces bomb Kurds in north for first time". Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ↑ Hawramy, Fazel (2016-08-22). "Kurdish militias fight against Syrian forces in north-east city of Hasaka". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑ Hawramy, Fazel (2016-08-22). "Kurdish militias fight against Syrian forces in north-east city of Hasaka". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑ Hawramy, Fazel (2016-08-22). "Kurdish militias fight against Syrian forces in north-east city of Hasaka". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ↑ "Clashes Between Kurdish and Jihadist Militants". Syriareport.net. 2013-05-04. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ↑ Syria Report (2013-05-27). "Insurgents Declare War on Syria's Kurds". Syriareport.net. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ↑ "Al-Hasakah: Deadly clashes between Arab tribes and PYD". KurdWatch. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Qamishli: PYD provokes supporters of the Kurdish National Council". KurdWatch. 4 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Qamishli: Youth groups organize three-day rally". KurdWatch. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Qamishli: PYD fails in attempt to mobilize one hundred thousand demonstrators". KurdWatch. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Qamishli: Kurdish Democratic Political Union—Syria established". KurdWatch. 7 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Qamishli: Shots exchanged between PYD and Yekîtî". KurdWatch. 12 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Ad-Darbasiyah: YPG abducts armed Yekîtî members". KurdWatch. 15 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Qamishli: YPG storms Yekîtî military drill ground". KurdWatch. 20 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Aleppo: Kurdish politician and writer fatally shot". KurdWatch. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Qamishli: More demonstrations in the Kurdish regions". Kurd Watch. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Malikiyah: YPG ends siege of Kahf al‑Assad". KurdWatch. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "ʿAyn al-ʿArab: YPG abducts Azadî members". KurdWatch. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ↑ "Diyarbakır mayors for Kurds in Syria". Firat News. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ "PYD increases attacks on other Kurdish groups in Syria". Daily Sabah. 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "Kurds fleeing Syria due to 'totalitarian' PYD's terror acts, oppressive attitude". Daily Sabah. 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Turkey bombs Kurdish headquarters northern Syria - ARA News". ARA News.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2016/08/28/world/middleeast/28reuters-mideast-crisis-syria-casualties.html?ref=asia&_r=0

- ↑ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/ap/article-3761219/Kurdish-led-Syrian-forces-report-Turkish-air-raids-bases.html

- ↑ http://rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/270820162

- ↑ Kurdish Forces Meet Turkish Demands, Leave Northern Syrian Town, Voice of America, 16 November 2016.

- ↑ YPG advances west of Euphrates towards al-Bab despite US pledges, Daily Sabah, 16 November 2016.

- ↑ US is not backing YPG offensive near al-Bab: Pentagon. Daily Sabah. 22 November 2016.

- ↑ "Coalition not backing Turkish move on Al-Bab: US". AFP. 17 November 2016.