Photography

| Other names | Science or Art of creating durable images |

|---|---|

| Types | Recording light or other electromagnetic radiation |

| Inventor | Thomas Wedgwood (1800) |

| Related | Stereoscopic, Full-spectrum, Light field, Electrophotography, Photograms, Scanner |

Photography is the science, art, application and practice of creating durable images by recording light or other electromagnetic radiation, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film.[1]

Typically, a lens is used to focus the light reflected or emitted from objects into a real image on the light-sensitive surface inside a camera during a timed exposure. With an electronic image sensor, this produces an electrical charge at each pixel, which is electronically processed and stored in a digital image file for subsequent display or processing. The result with photographic emulsion is an invisible latent image, which is later chemically "developed" into a visible image, either negative or positive depending on the purpose of the photographic material and the method of processing. A negative image on film is traditionally used to photographically create a positive image on a paper base, known as a print, either by using an enlarger or by contact printing.

Photography is employed in many fields of science, manufacturing (e.g., photolithography) and business, as well as its more direct uses for art, film and video production, recreational purposes, hobby, and mass communication.

Etymology

The word "photography" was created from the Greek roots φωτός (phōtos), genitive of φῶς (phōs), "light"[2] and γραφή (graphé) "representation by means of lines" or "drawing",[3] together meaning "drawing with light".[4]

Several people may have coined the same new term from these roots independently. Hercules Florence, a French painter and inventor living in Campinas, Brazil, used the French form of the word, photographie, in private notes which a Brazilian historian believes were written in 1834.[5] Johann von Maedler, a Berlin astronomer, is credited in a 1932 German history of photography as having used it in an article published on 25 February 1839 in the German newspaper Vossische Zeitung.[6] Both of these claims are now widely reported but apparently neither has ever been independently confirmed as beyond reasonable doubt. Credit has traditionally been given to Sir John Herschel both for coining the word and for introducing it to the public. His uses of it in private correspondence prior to 25 February 1839 and at his Royal Society lecture on the subject in London on 14 March 1839 have long been amply documented and accepted as settled facts.

History

Precursor technologies

Photography is the result of combining several technical discoveries. Long before the first photographs were made, ancient Han Chinese philosopher Mo Di from the Mohist School of Logic was the first to discover and develop the scientific principles of optics, camera obscura and pinhole camera. Later Greek mathematicians Aristotle and Euclid also independently described a pinhole camera in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.[7][8] In the 6th century CE, Byzantine mathematician Anthemius of Tralles used a type of camera obscura in his experiments,[9] Both the Han Chinese polymath Shen Kuo (1031–95) and Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) (965–1040) independently invented the camera obscura and pinhole camera,[8][10] Albertus Magnus (1193–1280) discovered silver nitrate,[11] and Georg Fabricius (1516–71) discovered silver chloride.[12] Shen Kuo explains the science of camera obscura and optical physics in his scientific work Dream Pool Essays while the techniques described in Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics are capable of producing primitive photographs using medieval materials.[13][14][15]

Daniele Barbaro described a diaphragm in 1566.[16] Wilhelm Homberg described how light darkened some chemicals (photochemical effect) in 1694.[17] The fiction book Giphantie, published in 1760, by French author Tiphaigne de la Roche, described what can be interpreted as photography.[16]

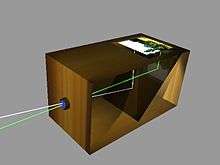

The discovery of the camera obscura that provides an image of a scene dates back to ancient China. Leonardo da Vinci mentions natural camera obscura that are formed by dark caves on the edge of a sunlit valley. A hole in the cave wall will act as a pinhole camera and project a laterally reversed, upside down image on a piece of paper. So the birth of photography was primarily concerned with inventing means to capture and keep the image produced by the camera obscura.

Renaissance painters used the camera obscura which, in fact, gives the optical rendering in color that dominates Western Art. The camera obscura literally means "dark chamber" in Latin. It is a box with a hole in it which allows light to go through and create an image onto the piece of paper.

Invention of photography

Around the year 1800, British inventor Thomas Wedgwood made the first known attempt to capture the image in a camera obscura by means of a light-sensitive substance. He used paper or white leather treated with silver nitrate. Although he succeeded in capturing the shadows of objects placed on the surface in direct sunlight, and even made shadow copies of paintings on glass, it was reported in 1802 that "the images formed by means of a camera obscura have been found too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver." The shadow images eventually darkened all over.[19]

The first permanent photoetching was an image produced in 1822 by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce, but it was destroyed in a later attempt to make prints from it.[18] Niépce was successful again in 1825. In 1826 or 1827, he made the View from the Window at Le Gras, the earliest surviving photograph from nature (i.e., of the image of a real-world scene, as formed in a camera obscura by a lens).[20]

Because Niépce's camera photographs required an extremely long exposure (at least eight hours and probably several days), he sought to greatly improve his bitumen process or replace it with one that was more practical. In partnership with Louis Daguerre, he worked out post-exposure processing methods that produced visually superior results and replaced the bitumen with a more light-sensitive resin, but hours of exposure in the camera were still required. With an eye to eventual commercial exploitation, the partners opted for total secrecy.

Niépce died in 1833 and Daguerre then redirected the experiments toward the light-sensitive silver halides, which Niépce had abandoned many years earlier because of his inability to make the images he captured with them light-fast and permanent. Daguerre's efforts culminated in what would later be named the daguerreotype process. The essential elements—a silver-plated surface sensitized by iodine vapor, developed by mercury vapor, and "fixed" with hot saturated salt water—were in place in 1837. The required exposure time was measured in minutes instead of hours. Daguerre took the earliest confirmed photograph of a person in 1838 while capturing a view of a Paris street: unlike the other pedestrian and horse-drawn traffic on the busy boulevard, which appears deserted, one man having his boots polished stood sufficiently still throughout the several-minutes-long exposure to be visible. The existence of Daguerre's process was publicly announced, without details, on 7 January 1839. The news created an international sensation. France soon agreed to pay Daguerre a pension in exchange for the right to present his invention to the world as the gift of France, which occurred when complete working instructions were unveiled on 19 August 1839.

In Brazil, Hercules Florence had apparently started working out a silver-salt-based paper process in 1832, later naming it Photographie.

Meanwhile, a British inventor, William Fox Talbot, had succeeded in making crude but reasonably light-fast silver images on paper as early as 1834 but had kept his work secret. After reading about Daguerre's invention in January 1839, Talbot published his hitherto secret method and set about improving on it. At first, like other pre-daguerreotype processes, Talbot's paper-based photography typically required hours-long exposures in the camera, but in 1840 he created the calotype process, which used the chemical development of a latent image to greatly reduce the exposure needed and compete with the daguerreotype. In both its original and calotype forms, Talbot's process, unlike Daguerre's, created a translucent negative which could be used to print multiple positive copies, this the basis of most modern chemical photography up to the present day, as Daguerreotypes could only be replicated by rephotographing them with a camera.[21] Talbot's famous tiny paper negative of the Oriel window in Lacock Abbey, one of a number of camera photographs he made in the summer of 1835, may be the oldest camera negative in existence.[22][23]

British chemist John Herschel made many contributions to the new field. He invented the cyanotype process, later familiar as the "blueprint". He was the first to use the terms "photography", "negative" and "positive". He had discovered in 1819 that sodium thiosulphate was a solvent of silver halides, and in 1839 he informed Talbot (and, indirectly, Daguerre) that it could be used to "fix" silver-halide-based photographs and make them completely light-fast. He made the first glass negative in late 1839.

In the March 1851 issue of The Chemist, Frederick Scott Archer published his wet plate collodion process. It became the most widely used photographic medium until the gelatin dry plate, introduced in the 1870s, eventually replaced it. There are three subsets to the collodion process; the Ambrotype (a positive image on glass), the Ferrotype or Tintype (a positive image on metal) and the glass negative, which was used to make positive prints on albumen or salted paper.

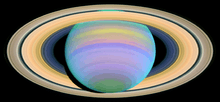

Many advances in photographic glass plates and printing were made during the rest of the 19th century. In 1891, Gabriel Lippmann introduced a process for making natural-color photographs based on the optical phenomenon of the interference of light waves. His scientifically elegant and important but ultimately impractical invention earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1908.

Glass plates were the medium for most original camera photography from the late 1850s until the general introduction of flexible plastic films during the 1890s. Although the convenience of the film greatly popularized amateur photography, early films were somewhat more expensive and of markedly lower optical quality than their glass plate equivalents, and until the late 1910s they were not available in the large formats preferred by most professional photographers, so the new medium did not immediately or completely replace the old. Because of the superior dimensional stability of glass, the use of plates for some scientific applications, such as astrophotography, continued into the 1990s, and in the niche field of laser holography it has persisted into the 2010s.

Film photography

Hurter and Driffield began pioneering work on the light sensitivity of photographic emulsions in 1876. Their work enabled the first quantitative measure of film speed to be devised.

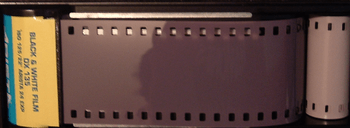

The first flexible photographic roll film was marketed by George Eastman in 1885, but this original "film" was actually a coating on a paper base. As part of the processing, the image-bearing layer was stripped from the paper and transferred to a hardened gelatin support. The first transparent plastic roll film followed in 1889. It was made from highly flammable nitrocellulose ("celluloid"), now usually called "nitrate film".

Although cellulose acetate or "safety film" had been introduced by Kodak in 1908,[24] at first it found only a few special applications as an alternative to the hazardous nitrate film, which had the advantages of being considerably tougher, slightly more transparent, and cheaper. The changeover was not completed for X-ray films until 1933, and although safety film was always used for 16 mm and 8 mm home movies, nitrate film remained standard for theatrical 35 mm motion pictures until it was finally discontinued in 1951.

Films remained the dominant form of photography until the early 21st century, when advances in digital photography drew consumers to digital formats.[25] Although modern photography is dominated by digital users, film continues to be used by enthusiasts and professional photographers. The distinctive "look" of film based photographs compared to digital images is likely due to a combination of factors, including: (1) differences in spectral and tonal sensitivity (S-shaped density-to-exposure (H&D curve) with film vs. linear response curve for digital CCD sensors) [26] (2) resolution and (3) continuity of tone.[27]

Black-and-white

Originally, all photography was monochrome, or black-and-white. Even after color film was readily available, black-and-white photography continued to dominate for decades, due to its lower cost and its "classic" photographic look. The tones and contrast between light and dark areas define black-and-white photography.[28] It is important to note that monochromatic pictures are not necessarily composed of pure blacks, whites, and intermediate shades of gray, but can involve shades of one particular hue depending on the process. The cyanotype process, for example, produces an image composed of blue tones. The albumen print process, first used more than 160 years ago, produces brownish tones.

Many photographers continue to produce some monochrome images, sometimes because of the established archival permanence of well-processed silver-halide-based materials. Some full-color digital images are processed using a variety of techniques to create black-and-white results, and some manufacturers produce digital cameras that exclusively shoot monochrome. Monochrome printing or electronic display can be used to salvage certain photographs taken in color which are unsatisfactory in their original form; sometimes when presented as black-and-white or single-color-toned images they are found to be more effective. Although color photography has long predominated, monochrome images are still produced, mostly for artistic reasons. Almost all digital cameras have an option to shoot in monochrome, and almost all image editing software can combine or selectively discard RGB color channels to produce a monochrome image from one shot in color.

Color

Color photography was explored beginning in the 1840s. Early experiments in color required extremely long exposures (hours or days for camera images) and could not "fix" the photograph to prevent the color from quickly fading when exposed to white light.

The first permanent color photograph was taken in 1861 using the three-color-separation principle first published by physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1855. Maxwell's idea was to take three separate black-and-white photographs through red, green and blue filters. This provides the photographer with the three basic channels required to recreate a color image. Transparent prints of the images could be projected through similar color filters and superimposed on the projection screen, an additive method of color reproduction. A color print on paper could be produced by superimposing carbon prints of the three images made in their complementary colors, a subtractive method of color reproduction pioneered by Louis Ducos du Hauron in the late 1860s.

Russian photographer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii made extensive use of this color separation technique, employing a special camera which successively exposed the three color-filtered images on different parts of an oblong plate. Because his exposures were not simultaneous, unsteady subjects exhibited color "fringes" or, if rapidly moving through the scene, appeared as brightly colored ghosts in the resulting projected or printed images.

Implementation of color photography was hindered by the limited sensitivity of early photographic materials, which were mostly sensitive to blue, only slightly sensitive to green, and virtually insensitive to red. The discovery of dye sensitization by photochemist Hermann Vogel in 1873 suddenly made it possible to add sensitivity to green, yellow and even red. Improved color sensitizers and ongoing improvements in the overall sensitivity of emulsions steadily reduced the once-prohibitive long exposure times required for color, bringing it ever closer to commercial viability.

Autochrome, the first commercially successful color process, was introduced by the Lumière brothers in 1907. Autochrome plates incorporated a mosaic color filter layer made of dyed grains of potato starch, which allowed the three color components to be recorded as adjacent microscopic image fragments. After an Autochrome plate was reversal processed to produce a positive transparency, the starch grains served to illuminate each fragment with the correct color and the tiny colored points blended together in the eye, synthesizing the color of the subject by the additive method. Autochrome plates were one of several varieties of additive color screen plates and films marketed between the 1890s and the 1950s.

Kodachrome, the first modern "integral tripack" (or "monopack") color film, was introduced by Kodak in 1935. It captured the three color components in a multi-layer emulsion. One layer was sensitized to record the red-dominated part of the spectrum, another layer recorded only the green part and a third recorded only the blue. Without special film processing, the result would simply be three superimposed black-and-white images, but complementary cyan, magenta, and yellow dye images were created in those layers by adding color couplers during a complex processing procedure.

Agfa's similarly structured Agfacolor Neu was introduced in 1936. Unlike Kodachrome, the color couplers in Agfacolor Neu were incorporated into the emulsion layers during manufacture, which greatly simplified the processing. Currently available color films still employ a multi-layer emulsion and the same principles, most closely resembling Agfa's product.

Instant color film, used in a special camera which yielded a unique finished color print only a minute or two after the exposure, was introduced by Polaroid in 1963.

Color photography may form images as positive transparencies, which can be used in a slide projector, or as color negatives intended for use in creating positive color enlargements on specially coated paper. The latter is now the most common form of film (non-digital) color photography owing to the introduction of automated photo printing equipment. After a transition period centered around 1995–2005, color film was relegated to a niche market by inexpensive multi-megapixel digital cameras. Film continues to be the preference of some photographers because of its distinctive "look".

Digital photography

In 1981, Sony unveiled the first consumer camera to use a charge-coupled device for imaging, eliminating the need for film: the Sony Mavica. While the Mavica saved images to disk, the images were displayed on television, and the camera was not fully digital. In 1991, Kodak unveiled the DCS 100, the first commercially available digital single lens reflex camera. Although its high cost precluded uses other than photojournalism and professional photography, commercial digital photography was born.

Digital imaging uses an electronic image sensor to record the image as a set of electronic data rather than as chemical changes on film.[29] An important difference between digital and chemical photography is that chemical photography resists photo manipulation because it involves film and photographic paper, while digital imaging is a highly manipulative medium. This difference allows for a degree of image post-processing that is comparatively difficult in film-based photography and permits different communicative potentials and applications.

Digital photography dominates the 21st century. More than 99% of photographs taken around the world are through digital cameras, increasingly through smartphones.

Synthesis photography

Synthesis photography is part of computer-generated imagery (CGI) where the shooting process is modeled on real photography. The CGI, creating digital copies of real universe, requires a visual representation process of these universes. Synthesis photography is the application of analog and digital photography in digital space. With the characteristics of the real photography but not being constrained by the physical limits of real world, synthesis photography allows to get away from real photography.[30]

Evolution of the camera

-

Late 19th century studio camera, standing on tripod, used glass photographic plates

-

Point-and-shoot box camera, the first type of mass-produced film camera, c. 1910s

-

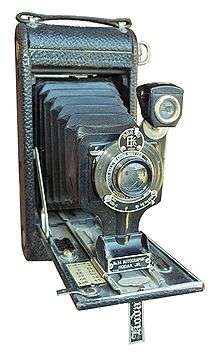

Compact Kodak folding camera from 1922

-

Contax S of 1949 – the first pentaprism SLR

-

Polaroid Colorpack 80 instant camera, c 1975

-

Digital camera, Canon Ixus class, c. 2000.

-

Nikon D1, the first digital SLR used in journalism and sports photography, c. 2000

-

Smartphone with built-in camera spreads private images globally, c. 2013

Technical aspects

The camera is the image-forming device, and a photographic plate, photographic film or a silicon electronic image sensor is the capture medium. The respective recording medium can be the plate or film itself, or a digital magnetic or electronic memory.[31]

Photographers control the camera and lens to "expose" the light-recording material to the required amount of light to form a "latent image" (on plate or film) or RAW file (in digital cameras) which, after appropriate processing, is converted to a usable image. Digital cameras use an electronic image sensor based on light-sensitive electronics such as charge-coupled device (CCD) or complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology. The resulting digital image is stored electronically, but can be reproduced on a paper.

The camera (or 'camera obscura') is a dark room or chamber from which, as far as possible, all light is excluded except the light that forms the image. The subject being photographed, however, must be illuminated. Cameras can range from small to very large, a whole room that is kept dark while the object to be photographed is in another room where it is properly illuminated. This was common for reproduction photography of flat copy when large film negatives were used (see Process camera).

As soon as photographic materials became "fast" (sensitive) enough for taking candid or surreptitious pictures, small "detective" cameras were made, some actually disguised as a book or handbag or pocket watch (the Ticka camera) or even worn hidden behind an Ascot necktie with a tie pin that was really the lens.

The movie camera is a type of photographic camera which takes a rapid sequence of photographs on recording medium. In contrast to a still camera, which captures a single snapshot at a time, the movie camera takes a series of images, each called a "frame". This is accomplished through an intermittent mechanism. The frames are later played back in a movie projector at a specific speed, called the "frame rate" (number of frames per second). While viewing, a person's eyes and brain merge the separate pictures together to create the illusion of motion.[32]

Camera controls

In all but certain specialized cameras, the process of obtaining a usable exposure must involve the use, manually or automatically, of a few controls to ensure the photograph is clear, sharp and well illuminated. The controls usually include but are not limited to the following:

| Control | Description |

|---|---|

| Focus | The position of a viewed object or the adjustment of an optical device necessary to produce a clear image: in focus; out of focus.[33] |

| Aperture | Adjustment of the lens opening, measured as f-number, which controls the amount of light passing through the lens. Aperture also has an effect on depth of field and diffraction – the higher the f-number, the smaller the opening, the less light, the greater the depth of field, and the more the diffraction blur. The focal length divided by the f-number gives the effective aperture diameter. |

| Shutter speed | Adjustment of the speed (often expressed either as fractions of seconds or as an angle, with mechanical shutters) of the shutter to control the amount of time during which the imaging medium is exposed to light for each exposure. Shutter speed may be used to control the amount of light striking the image plane; 'faster' shutter speeds (that is, those of shorter duration) decrease both the amount of light and the amount of image blurring from motion of the subject and/or camera. The slower shutter speeds allow for long exposure shots that are done used to photograph images in very low light, including the images of the night sky. |

| White balance | On digital cameras, electronic compensation for the color temperature associated with a given set of lighting conditions, ensuring that white light is registered as such on the imaging chip and therefore that the colors in the frame will appear natural. On mechanical, film-based cameras, this function is served by the operator's choice of film stock or with color correction filters. In addition to using white balance to register natural coloration of the image, photographers may employ white balance to aesthetic end, for example white balancing to a blue object in order to obtain a warm color temperature. |

| Metering | Measurement of exposure so that highlights and shadows are exposed according to the photographer's wishes. Many modern cameras meter and set exposure automatically. Before automatic exposure, correct exposure was accomplished with the use of a separate light metering device or by the photographer's knowledge and experience of gauging correct settings. To translate the amount of light into a usable aperture and shutter speed, the meter needs to adjust for the sensitivity of the film or sensor to light. This is done by setting the "film speed" or ISO sensitivity into the meter. |

| Film speed | Traditionally used to "tell the camera" the film speed of the selected film on film cameras, film speed numbers are employed on modern digital cameras as an indication of the system's gain from light to numerical output and to control the automatic exposure system. Film speed is usually measured via the ISO system. The higher the film speed number the greater the film sensitivity to light, whereas with a lower number, the film is less sensitive to light. A correct combination of film speed, aperture, and shutter speed leads to an image that is neither too dark nor too light, hence it is 'correctly exposed', indicated by a centered meter. |

| Autofocus point | On some cameras, the selection of a point in the imaging frame upon which the auto-focus system will attempt to focus. Many Single-lens reflex cameras (SLR) feature multiple auto-focus points in the viewfinder. |

Many other elements of the imaging device itself may have a pronounced effect on the quality and/or aesthetic effect of a given photograph; among them are:

- Focal length and type of lens (normal, long focus, wide angle, telephoto, macro, fisheye, or zoom)

- Filters placed between the subject and the light recording material, either in front of or behind the lens

- Inherent sensitivity of the medium to light intensity and color/wavelengths.

- The nature of the light recording material, for example its resolution as measured in pixels or grains of silver halide.

Exposure and rendering

Camera controls are interrelated. The total amount of light reaching the film plane (the 'exposure') changes with the duration of exposure, aperture of the lens, and on the effective focal length of the lens (which in variable focal length lenses, can force a change in aperture as the lens is zoomed). Changing any of these controls can alter the exposure. Many cameras may be set to adjust most or all of these controls automatically. This automatic functionality is useful for occasional photographers in many situations.

The duration of an exposure is referred to as shutter speed, often even in cameras that do not have a physical shutter, and is typically measured in fractions of a second. It is quite possible to have exposures from one up to several seconds, usually for still-life subjects, and for night scenes exposure times can be several hours. However, for a subject that is in motion use a fast shutter speed. This will prevent the photograph from coming out blurry.[35]

The effective aperture is expressed by an f-number or f-stop (derived from focal ratio), which is proportional to the ratio of the focal length to the diameter of the aperture. Longer focal length lenses will pass less light through the same aperture diameter due to the greater distance the light has to travel; shorter focal length lenses will transmit more light through the same diameter of aperture.

The smaller the f/number, the larger the effective aperture. The present system of f/numbers to give the effective aperture of a lens was standardized by an international convention in 1963, and is referred to as the British Standard (BS-1013).[36] Other aperture measurement scales had been used through the early 20th century, including the European Scale, Intermediate settings, and the 1881 Uniform System proposed by the Royal Photographic Society, which are all now largely obsolete.[37]:30 T-stops have been used for color motion picture lenses, to account for differences in light transmission through compound lenses, are calculated as T-number = f/number x √transmittance.[37]:615

If the f-number is decreased by a factor of √2, the aperture diameter is increased by the same factor, and its area is increased by a factor of 2. The f-stops that might be found on a typical lens include 2.8, 4, 5.6, 8, 11, 16, 22, 32, where going up "one stop" (using lower f-stop numbers) doubles the amount of light reaching the film, and stopping down one stop halves the amount of light.

Image capture can be achieved through various combinations of shutter speed, aperture, and film or sensor speed. Different (but related) settings of aperture and shutter speed enable photographs to be taken under various conditions of film or sensor speed, lighting and motion of subjects and/or camera, and desired depth of field. A slower speed film will exhibit less "grain", and a slower speed setting on an electronic sensor will exhibit less "noise", while higher film and sensor speeds allow for a faster shutter speed, which reduces motion blur or allows the use of a smaller aperture to increase the depth of field.

For example, a wider aperture is used for lower light and a lower aperture for more light. If a subject is in motion, then a high shutter speed may be needed. A tripod can also be helpful in that it enables a slower shutter speed to be used.

For example, f/8 at 8 ms (1/125 of a second) and f/5.6 at 4 ms (1/250 of a second) yield the same amount of light. The chosen combination affects the final result. The aperture and focal length of the lens determine the depth of field, which refers to the range of distances from the lens that will be in focus. A longer lens or a wider aperture will result in "shallow" depth of field (i.e., only a small plane of the image will be in sharp focus). This is often useful for isolating subjects from backgrounds as in individual portraits or macro photography.

Conversely, a shorter lens, or a smaller aperture, will result in more of the image being in focus. This is generally more desirable when photographing landscapes or groups of people. With very small apertures, such as pinholes, a wide range of distance can be brought into focus, but sharpness is severely degraded by diffraction with such small apertures. Generally, the highest degree of "sharpness" is achieved at an aperture near the middle of a lens's range (for example, f/8 for a lens with available apertures of f/2.8 to f/16). However, as lens technology improves, lenses are becoming capable of making increasingly sharp images at wider apertures.

Image capture is only part of the image forming process. Regardless of material, some process must be employed to render the latent image captured by the camera into a viewable image. With slide film, the developed film is just mounted for projection. Print film requires the developed film negative to be printed onto photographic paper or transparency. Prior to the advent of laser jet and inkjet printers, celluloid photographic negative images had to be mounted in an enlarger which projected the image onto a sheet of light-sensitive paper for a certain length of time (usually measured in seconds or fractions of a second). This sheet then was soaked in a chemical bath of developer (to bring out the image) followed immediately by a stop bath (to neutralize the progression of development and prevent the image from changing further once exposed to normal light). After this, the paper was hung until dry enough to safely handle. This post-production process allowed the photographer to further manipulate the final image beyond what had already been captured on the negative, adjusting the length of time the image was projected by the enlarger and the duration of both chemical baths to change the image's intensity, darkness, clarity, etc. This process is still employed by both amateur and professional photographers, but the advent of digital imagery means that the vast majority of modern photographic work is captured digitally and rendered via printing processes that are no longer dependent on chemical reactions to light. Such digital images may be uploaded to an image server (e.g., a photo-sharing web site), viewed on a television, or transferred to a computer or digital photo frame. Every type can then be produced as a hard copy on regular paper or photographic paper via a printer.

Prior to the rendering of a viewable image, modifications can be made using several controls. Many of these controls are similar to controls during image capture, while some are exclusive to the rendering process. Most printing controls have equivalent digital concepts, but some create different effects. For example, dodging and burning controls are different between digital and film processes. Other printing modifications include:

- Chemicals and process used during film development.

- Duration of print exposure – equivalent to shutter speed

- Printing aperture – equivalent to aperture, but has no effect on depth of field

- Contrast – changing the visual properties of objects in an image to make them distinguishable from other objects and the background

- Dodging – reduces exposure of certain print areas, resulting in lighter areas

- Burning in – increases exposure of certain areas, resulting in darker areas

- Paper texture – glossy, matte, etc.

- Paper type – resin-coated (RC) or fiber-based (FB)

- Paper size

- Exposure shape – resulting prints in shapes such as circular, oval, loupe, etc.

- Toners – used to add warm or cold tones to black-and-white prints

Other photographic techniques

Stereoscopic

Photographs, both monochrome and color, can be captured and displayed through two side-by-side images that emulate human stereoscopic vision. Stereoscopic photography was the first that captured figures in motion.[38] While known colloquially as "3-D" photography, the more accurate term is stereoscopy. Such cameras have long been realized by using film, and more recently in digital electronic methods (including cellphone cameras).

Full-spectrum, ultraviolet and infrared

Ultraviolet and infrared films have been available for many decades and employed in a variety of photographic avenues since the 1960s. New technological trends in digital photography have opened a new direction in full spectrum photography, where careful filtering choices across the ultraviolet, visible and infrared lead to new artistic visions.

Modified digital cameras can detect some ultraviolet, all of the visible and much of the near infrared spectrum, as most digital imaging sensors are sensitive from about 350 nm to 1000 nm. An off-the-shelf digital camera contains an infrared hot mirror filter that blocks most of the infrared and a bit of the ultraviolet that would otherwise be detected by the sensor, narrowing the accepted range from about 400 nm to 700 nm.[39]

Replacing a hot mirror or infrared blocking filter with an infrared pass or a wide spectrally transmitting filter allows the camera to detect the wider spectrum light at greater sensitivity. Without the hot-mirror, the red, green and blue (or cyan, yellow and magenta) colored micro-filters placed over the sensor elements pass varying amounts of ultraviolet (blue window) and infrared (primarily red and somewhat lesser the green and blue micro-filters).

Uses of full spectrum photography are for fine art photography, geology, forensics and law enforcement.

Light field photography

Digital methods of image capture and display processing have enabled the new technology of "light field photography" (also known as synthetic aperture photography). This process allows focusing at various depths of field to be selected after the photograph has been captured.[40] As explained by Michael Faraday in 1846, the "light field" is understood as 5-dimensional, with each point in 3-D space having attributes of two more angles that define the direction of each ray passing through that point.

These additional vector attributes can be captured optically through the use of microlenses at each pixel-point within the 2-dimensional image sensor. Every pixel of the final image is actually a selection from each sub-array located under each microlens, as identified by a post-image capture focus algorithm.

Other imaging techniques

Besides the camera, other methods of forming images with light are available. For instance, a photocopy or xerography machine forms permanent images but uses the transfer of static electrical charges rather than photographic medium, hence the term electrophotography. Photograms are images produced by the shadows of objects cast on the photographic paper, without the use of a camera. Objects can also be placed directly on the glass of an image scanner to produce digital pictures.

Modes of production

Amateur

An amateur photographer is one who practices photography as a hobby / passion and not for profit. The quality of some amateur work is comparable to that of many professionals and may be highly specialized or eclectic in choice of subjects. Amateur photography is often pre-eminent in photographic subjects which have little prospect of commercial use or reward. Amateur photography grew during the late 19th century due to the popularization of the hand-held camera.[41] Nowadays it has spread widely through social media and is carried out throughout different platforms and equipment, switching to the use of cellphone as a key tool for making photography more accessible to everyone.

Commercial

Commercial photography is probably best defined as any photography for which the photographer is paid for images rather than works of art. In this light, money could be paid for the subject of the photograph or the photograph itself. Wholesale, retail, and professional uses of photography would fall under this definition. The commercial photographic world could include:

- Advertising photography: photographs made to illustrate and usually sell a service or product. These images, such as packshots, are generally done with an advertising agency, design firm or with an in-house corporate design team.

- Fashion and glamour photography usually incorporates models and is a form of advertising photography. Fashion photography, like the work featured in Harper's Bazaar, emphasizes clothes and other products; glamour emphasizes the model and body form. Glamour photography is popular in advertising and men's magazines. Models in glamour photography sometimes work nude

- Concert Photography focuses on capturing candid images of both the artist or band as well as the atmosphere (including the crowd). Many of these photographers work freelance and are contracted through an artist or their management to cover a specific show. Concert photographs are often used to promote the artist or band in addition to the venue.

- Crime scene photography consists of photographing scenes of crime such as robberies and murders. A black and white camera or an infrared camera may be used to capture specific details.

- Still life photography usually depicts inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which may be either natural or man-made. Still life is a broader category for food and some natural photography and can be used for advertising purposes.

- Food photography can be used for editorial, packaging or advertising use. Food photography is similar to still life photography, but requires some special skills.

- Editorial photography illustrates a story or idea within the context of a magazine. These are usually assigned by the magazine and encompass fashion and glamour photography features.

- Photojournalism can be considered a subset of editorial photography. Photographs made in this context are accepted as a documentation of a news story.

- Portrait and wedding photography: photographs made and sold directly to the end user of the images.

- Landscape photography depicts locations.

- Wildlife photography demonstrates the life of animals.

- Paparazzi is a form of photojournalism in which the photographer captures candid images of athletes, celebrities, politicians, and other prominent people.

- Pet photography involves several aspects that are similar to traditional studio portraits. It can also be done in natural lighting, outside of a studio, such as in a client's home.

The market for photographic services demonstrates the aphorism "A picture is worth a thousand words", which has an interesting basis in the history of photography. Magazines and newspapers, companies putting up Web sites, advertising agencies and other groups pay for photography.

Many people take photographs for commercial purposes. Organizations with a budget and a need for photography have several options: they can employ a photographer directly, organize a public competition, or obtain rights to stock photographs. Photo stock can be procured through traditional stock giants, such as Getty Images or Corbis; smaller microstock agencies, such as Fotolia; or web marketplaces, such as Cutcaster.

Art

During the 20th century, both fine art photography and documentary photography became accepted by the English-speaking art world and the gallery system. In the United States, a handful of photographers, including Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, John Szarkowski, F. Holland Day, and Edward Weston, spent their lives advocating for photography as a fine art. At first, fine art photographers tried to imitate painting styles. This movement is called Pictorialism, often using soft focus for a dreamy, 'romantic' look. In reaction to that, Weston, Ansel Adams, and others formed the Group f/64 to advocate 'straight photography', the photograph as a (sharply focused) thing in itself and not an imitation of something else.

The aesthetics of photography is a matter that continues to be discussed regularly, especially in artistic circles. Many artists argued that photography was the mechanical reproduction of an image. If photography is authentically art, then photography in the context of art would need redefinition, such as determining what component of a photograph makes it beautiful to the viewer. The controversy began with the earliest images "written with light"; Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, and others among the very earliest photographers were met with acclaim, but some questioned if their work met the definitions and purposes of art.

Clive Bell in his classic essay Art states that only "significant form" can distinguish art from what is not art.

There must be some one quality without which a work of art cannot exist; possessing which, in the least degree, no work is altogether worthless. What is this quality? What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to Sta. Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl, Chinese carpets, Giotto's frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cezanne? Only one answer seems possible — significant form. In each, lines and colors combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions.[43]

On 14 February 2004, Sotheby's London sold the 2001 photograph 99 Cent II Diptychon for an unprecedented $3,346,456 to an anonymous bidder, making it the most expensive at the time.

Conceptual photography turns a concept or idea into a photograph. Even though what is depicted in the photographs are real objects, the subject is strictly abstract.

Science and forensics

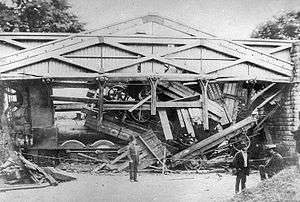

The camera has a long and distinguished history as a means of recording scientific phenomena from the first use by Daguerre and Fox-Talbot, such as astronomical events (eclipses for example), small creatures and plants when the camera was attached to the eyepiece of microscopes (in photomicroscopy) and for macro photography of larger specimens. The camera also proved useful in recording crime scenes and the scenes of accidents, such as the Wootton bridge collapse in 1861. The methods used in analysing photographs for use in legal cases are collectively known as forensic photography. Crime scene photos are taken from three vantage point. The vantage points are overview, mid-range, and close up.[44]

In 1845 Francis Ronalds, the Honorary Director of the Kew Observatory, invented the first successful camera to make continuous recordings of meteorological and geomagnetic parameters. Different machines produced 12- or 24- hour photographic traces of the minute-by-minute variations of atmospheric pressure, temperature, humidity, atmospheric electricity, and the three components of geomagnetic forces. The cameras were supplied to numerous observatories around the world and some remained in use until well into the 20th century.[45][46] Charles Brooke a little later developed similar instruments for the Greenwich Observatory.[47]

Science uses image technology that has derived from the design of the Pin Hole camera. X-Ray machine are similar in design to Pin Hole cameras with high grade filters and laser radiation.[48] Photography has become ubiquitous in recording events and data in science and engineering, and at crime scenes or accident scenes. The method has been much extended by using other wavelengths, such as infrared photography and ultraviolet photography, as well as spectroscopy. Those methods were first used in the Victorian era and improved much further since that time.[49]

The first photographed atom was discovered in 2012 by physicists at Griffith University, Australia. They used an electric field to trap an "Ion" of the element, Ytterbium. The image was recorded on a CCD, an electronic photographic film.[50]

Social and cultural implications

.jpg)

There are many ongoing questions about different aspects of photography. In her writing "On Photography" (1977), Susan Sontag discusses concerns about the objectivity of photography. This is a highly debated subject within the photographic community.[51] Sontag argues, "To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting one's self into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge, and therefore like power."[52] Photographers decide what to take a photo of, what elements to exclude and what angle to frame the photo, and these factors may reflect a particular socio-historical context. Along these lines it can be argued that photography is a subjective form of representation.

Modern photography has raised a number of concerns on its effect on society. In Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window (1954), the camera is presented as promoting voyeurism. 'Although the camera is an observation station, the act of photographing is more than passive observing'.[52]

The camera doesn't rape or even possess, though it may presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit, and, at the farthest reach of metaphor, assassinate – all activities that, unlike the sexual push and shove, can be conducted from a distance, and with some detachment.[52]

Digital imaging has raised ethical concerns because of the ease of manipulating digital photographs in post-processing. Many photojournalists have declared they will not crop their pictures, or are forbidden from combining elements of multiple photos to make "photomontages", passing them as "real" photographs. Today's technology has made image editing relatively simple for even the novice photographer. However, recent changes of in-camera processing allows digital fingerprinting of photos to detect tampering for purposes of forensic photography.

Photography is one of the new media forms that changes perception and changes the structure of society.[53] Further unease has been caused around cameras in regards to desensitization. Fears that disturbing or explicit images are widely accessible to children and society at large have been raised. Particularly, photos of war and pornography are causing a stir. Sontag is concerned that "to photograph is to turn people into objects that can be symbolically possessed." Desensitization discussion goes hand in hand with debates about censored images. Sontag writes of her concern that the ability to censor pictures means the photographer has the ability to construct reality.[52]

One of the practices through which photography constitutes society is tourism. Tourism and photography combine to create a "tourist gaze"[54] in which local inhabitants are positioned and defined by the camera lens. However, it has also been argued that there exists a "reverse gaze"[55] through which indigenous photographees can position the tourist photographer as a shallow consumer of images.

Additionally, photography has been the topic of many songs in popular culture.

Law

Photography is both restricted as well as protected by the law in many jurisdictions. Protection of photographs is typically achieved through the granting of copyright or moral rights to the photographer. In the United States, photography is protected as a First Amendment right and anyone is free to photograph anything seen in public spaces as long as it is in plain view.[56] In the UK a recent law (Counter-Terrorism Act 2008) increases the power of the police to prevent people, even press photographers, from taking pictures in public places.[57]

See also

References

- ↑ Spencer, D A (1973). The Focal Dictionary of Photographic Technologies. Focal Press. p. 454. ISBN 978-0133227192.

- ↑ φάος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ γραφή, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "photograph". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Boris Kossoy (2004). Hercule Florence: El descubrimiento de la fotografía en Brasil. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. ISBN 968-03-0020-X.

- ↑ Eder, J.M (1945) [1932]. History of Photography, 4th. edition [Geschichte der Photographie]. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 258–259. ISBN 0-486-23586-6.

- ↑ Campbell, Jan (2005) Film and cinema spectatorship: melodrama and mimesis. Polity. p. 114. ISBN 0-7456-2930-X

- 1 2 Krebs, Robert E. (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 20. ISBN 0-313-32433-6.

- ↑ Alistair Cameron Crombie, Science, optics, and music in medieval and early modern thought, p. 205

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas J.; Finger, Stanley (2001). "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective". Perception. 30 (10): 1157–77. doi:10.1068/p3210. PMID 11721819.

- ↑ Davidson, Michael W; National High Magnetic Field Laboratory at The Florida State University (1 August 2003). "Molecular Expressions: Science, Optics and You – Timeline – Albertus Magnus". The Florida State University. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ↑ Potonniée, Georges (1973). The history of the discovery of photography. Arno Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-405-04929-3

- ↑ Allen, Nicholas P. L. (11 November 1993). "Is the Shroud of Turin the first recorded photograph?" (PDF). The South African Journal of Art History: 23–32.

- ↑ Allen, Nicholas P. L. (1994). "A reappraisal of late thirteenth-century responses to the Shroud of Lirey-Chambéry-Turin: encolpia of the Eucharist, vera eikon or supreme relic?". The Southern African Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 4 (1): 62–94.

- ↑ Allen, Nicholas P. L. "Verification of the Nature and Causes of the Photo-negative Images on the Shroud of Lirey-Chambéry-Turin". unisa.ac.za

- 1 2 Gernsheim, Helmut (1986). A concise history of photography. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-486-25128-4

- ↑ Gernsheim, Helmut and Gernsheim, Alison (1955) The history of photography from the earliest use of the camera obscura in the eleventh century up to 1914. Oxford University Press. p. 20.

- 1 2 "The First Photograph – Heliography". Retrieved 29 September 2009.

from Helmut Gernsheim's article, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, January 1977: ...In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate... The sunlight passing through... This first permanent example... was destroyed... some years later.

- ↑ Litchfield, R. 1903. "Tom Wedgwood, the First Photographer: An Account of His Life." London, Duckworth and Co. See Chapter XIII. Includes the complete text of Humphry Davy's 1802 paper, which is the only known contemporary record of Wedgwood's experiments. (Retrieved 7 May 2013 via archive.org).

- ↑ Hirsch, Robert (2000). Seizing the light: a history of photography. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-697-14361-7.

- ↑ William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877). BBC

- ↑ Feldman, Anthony and Ford, Peter (1989) Scientists & inventors. Bloomsbury Books, p. 128, ISBN 1870630238.

- ↑ Fox Talbot, William Henry and Jammes, André (1973) William H. Fox Talbot, inventor of the negative-positive process, Macmillan, p. 95.

- ↑ History of Kodak, Milestones-chronology: 1878-1929. kodak.com

- ↑ Peres, Michael R. (2008). The Concise Focal Encyclopedia of Photography: from the first photo on paper to the digital revolution. Burlington, Mass.: Focal Press/Elsevier. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-240-80998-4.

- ↑ "H&D curve of film vs digital". Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ↑ Jacobson, Ralph E. (2000). The Focal Manual of Photography: photographic and digital imaging (9th ed.). Boston, Mass.: Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-240-51574-8.

- ↑ "Black & White Photography". PSA Journal. 77 (12): 38–40. 2011.

- ↑ Schewe, Jeff (2012). The Digital Negative: Raw Image Processing In Lightroom, Camera Raw, and Photoshop. Berkeley, CA: Peachpit Press, ISBN 0321839579, p. 72

- ↑ Paux, Marc-Olivier (1 February 2011). Synthesis photography and architecture. Imagina. Monaco.

- ↑ "Glossary: Digital Photography Review". Dpreview.com. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ Anderson, Joseph; Anderson, Barbara (Spring 1993). "The Myth of Persistence of Vision Revisited". Journal of Film and Video. 45 (1): 3–12. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009.

- ↑ "Definition of focus". IAC. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ "Star Trails over the VLT in Paranal". ESO Picture of the Week. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ↑ Fisher, Jim (2013). "Take Picture-Perfect Digital Photos." PC Magazine: 134–141.

- ↑ British Standards Institution (1963). Photographic lenses: Definitions, methods and accuraccy of marking (British Standard 1019) (2nd ed.). British Standards Institution. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- 1 2 Spencer, Douglas A. (1973). The focal dictionary of photographic technologies. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0133227192.

- ↑ Belisle, Brooke (2013). "The Dimensional Image: Overlaps In Stereoscopic, Cinematic, And Digital Depth." Film Criticism 37/38 (3/1): 117–137. Academic Search Complete. Web. 3 October 2013.

- ↑ Twede, David. Introduction to Full-Spectrum and Infrared photography. surrealcolor.110mb.com

- ↑ Ng, Ren (July 2006) Digital Light Field Photography. PhD Thesis, Stanford University

- ↑ Peterson, C. A. (2011). "Home Portraiture". History of Photography. 35 (4): 374. doi:10.1080/03087298.2011.606727.

- ↑ "All Around Chajnantor – A 360-degree panorama". ESO Picture of the Week. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ Clive Bell. "Art", 1914. Retrieved 2 September 2006.

- ↑ Rohde, R. R. (2000). Crime Photography. PSA Journal, 66(3), 15.

- ↑ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ↑ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). "The Beginnings of Continuous Scientific Recording using Photography: Sir Francis Ronalds' Contribution". European Society for the History of Photography. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Photographic self-registering magnetic and meteorological apparatus: Invented by Mr. Brooke of Keppel-Street, London". The Illustrated Magazine of Art. New York: Alexander Montgomery. 1: 308–311. 1853.

- ↑ Upadhyay, J.; Chakera, J. A.; Navathe, C. P.; Naik, P. A.; Joshi, A. S.; Gupta, P. D. (2006). "Development of single frame X-ray framing camera for pulsed plasma experiments". Sadhana. 31 (5): 613. doi:10.1007/BF02715917.

- ↑ Blitzer, Herbert L.; Stein-Ferguson, Karen; Huang, Jeffrey (2008). Understanding forensic digital imaging. Academic Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-12-370451-1.

- ↑ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guiness Book of Records 2014. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ↑ Bissell, K.L. (2000) Photography and Objectivity.

- 1 2 3 4 Sontag, S. (1977) On Photography, Penguin, London, pp. 3–24, ISBN 0312420099.

- ↑ Levinson, P. (1997) The Soft Edge: a Natural History and Future of the Information Revolution, Routledge, London and New York, pp. 37–48, ISBN 0415157854.

- ↑ Urry, John (2002). The tourist gaze (2nd ed.). SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-7347-8.

- ↑ Gillespie, Alex. "Tourist Photography and the Reverse Gaze".

- ↑ "You Have Every Right to Photograph That Cop". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Jail for photographing police?". British Journal of Photography. 28 January 2009. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010.

Further reading

Introduction

- Photography. A Critical Introduction [Paperback], ed. by Liz Wells, 3rd edition, London [etc.]: Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-30704-X

History

- A New History of Photography, ed. by Michel Frizot, Köln : Könemann, 1998

- Franz-Xaver Schlegel, Das Leben der toten Dinge – Studien zur modernen Sachfotografie in den USA 1914–1935, 2 Bände, Stuttgart/Germany: Art in Life 1999, ISBN 3-00-004407-8.

Reference works

- Tom Ang (2002). Dictionary of Photography and Digital Imaging: The Essential Reference for the Modern Photographer. Watson-Guptill. ISBN 0-8174-3789-4.

- Hans-Michael Koetzle: Das Lexikon der Fotografen: 1900 bis heute, Munich: Knaur 2002, 512 p., ISBN 3-426-66479-8

- John Hannavy (ed.): Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, 1736 p., New York: Routledge 2005 ISBN 978-0-415-97235-2

- Lynne Warren (Hrsg.): Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography, 1719 p., New York, NY [et.] : Routledge, 2006

- The Oxford Companion to the Photograph, ed. by Robin Lenman, Oxford University Press 2005

- "The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography", Richard Zakia, Leslie Stroebel, Focal Press 1993, ISBN 0-240-51417-3

Other books

- Photography and The Art of Seeing by Freeman Patterson, Key Porter Books 1989, ISBN 1-55013-099-4.

- The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression by Bruce Barnbaum, Rocky Nook 2010, ISBN 1-933952-68-7.

- Image Clarity: High Resolution Photography by John B. Williams, Focal Press 1990, ISBN 0-240-80033-8.

External links

- Photography at DMOZ

- World History of Photography From The History of Art.

- Daguerreotype to Digital: A Brief History of the Photographic Process From the State Library & Archives of Florida.

- Photography Changes Everything is a collection of original essays, stories and images—contributed by experts from a spectrum of professional worlds and members of the project's online audience—that explore the many ways photography shapes our culture and our lives, by the Smithsonian Institution.