Panama City

| Panama City | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| Ciudad de Panamá | |||

|

Top to bottom, left to right: Panama Canal, Skyline, Bridge of the Americas, The bovedas, Casco Viejo of Panama and Metropolitan Cathedral of Panama. | |||

| |||

Panama City | |||

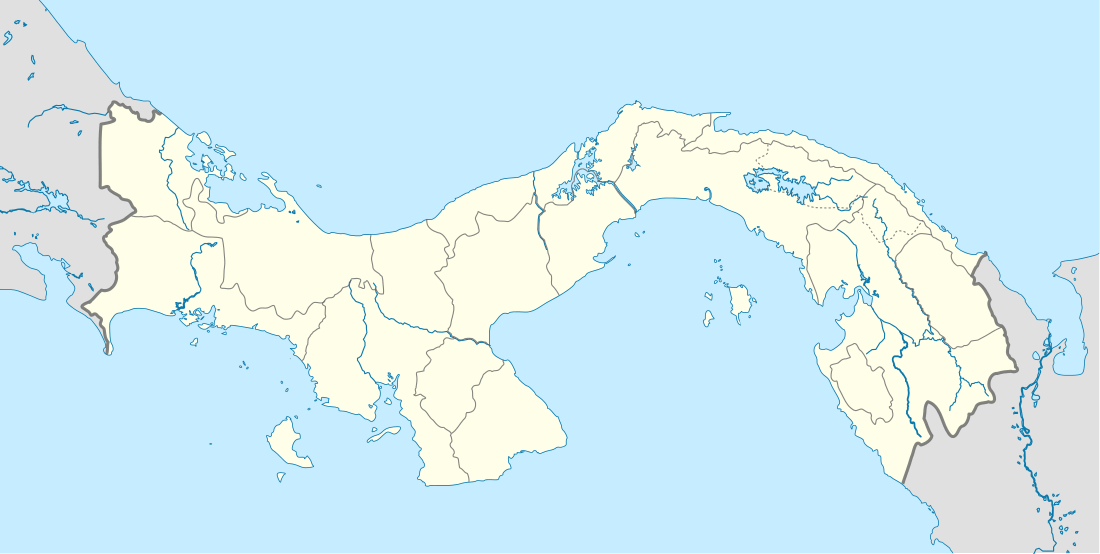

| Coordinates: Country 8°59′N 79°31′W / 8.983°N 79.517°W | |||

| District | Panamá | ||

| Foundation | August 15, 1519 | ||

| Founded by | Pedro Arias de Ávila | ||

| Government | |||

| • President | Juan Carlos Varela | ||

| • Mayor | José Isabel Blandón Figueroa | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 275 km2 (106 sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 2,560.8 km2 (988.7 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 2 m (7 ft) | ||

| Population (2013) | |||

| • City | 880,691 | ||

| • Density | 5,750/km2 (7,656/sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 430,299 | ||

| [1] | |||

| Area code(s) | (+507) 2 | ||

| HDI (2007) | 0.780 – high[2] | ||

| Website | mupa.gob.pa | ||

Panama City (Spanish: Ciudad de Panamá; pronounced: [sjuˈða(ð) ðe panaˈma]) is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Panama.[3][4] It has an urban population of 430,299,[1] and its population totals 880,691 when rural areas are included.[1] The city is located at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal, in the province of Panama. The city is the political and administrative center of the country, as well as a hub for international banking and commerce.[5] It is considered a "gamma+" world city, one of three Central American cities listed in this category.[6]

The city of Panama has an average GDP per capita of $15,300.[7] It has a dense skyline of mostly high-rise buildings, and it is surrounded by a large belt of tropical rainforest. Panama's Tocumen International Airport, the largest and busiest airport in Central America, offers daily flights to major international destinations. Panama was chosen as the 2003 American Capital of Culture jointly with Curitiba, Brazil. It is among the top five places for retirement in the world, according to International Living magazine.

The city of Panama was founded on August 15, 1519, by Spanish conquistador Pedro Arias Dávila. The city was the starting point for expeditions that conquered the Inca Empire in Peru. It was a stopover point on one of the most important trade routes in the history of the American continent, leading to the fairs of Nombre de Dios and Portobelo, through which passed most of the gold and silver that Spain took from the Americas.

On January 28, 1671, the original city (see Panamá Viejo) was destroyed by a fire when privateer Henry Morgan sacked and set fire to it. The city was formally reestablished two years later on January 21, 1673, in a peninsula located 8 km (5 miles) from the original settlement. The site of the previously devastated city is still in ruins and is now a popular tourist attraction known as Panama Viejo.

History

_(14597444780).jpg)

The city was founded on August 15, 1519, by Pedro Arias de Ávila, also known as Pedrarias Dávila. Within a few years of its founding, the city became a launching point for the exploration and conquest of Peru and a transit point for gold and silver headed back to Spain through the Isthmus. In 1671 Henry Morgan with a band of 1400 men attacked and looted the city, which was subsequently destroyed by fire. The ruins of the old city still remain and are a popular tourist attraction known as Panamá la Vieja (Old Panama). It was rebuilt in 1673 in a new location approximately 5 miles (8 km) southwest of the original city. This location is now known as the Casco Viejo (Old Quarter) of the city.

One year before the start of the California Gold Rush, the Panama Railroad Company was formed, but the railroad did not begin operation until 1855. Between 1848 and 1869, the year the first transcontinental railroad was completed in the United States, about 375,000 persons crossed the isthmus from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and 225,000 in the opposite direction. That traffic greatly increased the prosperity of the city during that period.

The construction of the Panama Canal was of great benefit to the infrastructure and economy. Of particular note are the improvements in health and sanitation brought about by the American presence in the Canal Zone. Dr. William Gorgas, the chief sanitary officer for the canal construction, had a particularly large impact. He hypothesized that diseases were spread by the abundance of mosquitos native to the area, and ordered the fumigation of homes and the cleansing of water. This led to yellow fever being eradicated by November 1905, as well malaria rates falling dramatically.[8] However, most of the laborers for the construction of the canal were brought in from the Caribbean, which created unprecedented racial and social tensions in the city.

During World War II, construction of military bases and the presence of larger numbers of U.S. military and civilian personnel brought about unprecedented levels of prosperity to the city. Panamanians had limited access, or no access at all, to many areas in the Canal Zone neighboring the Panama city metropolitan area. Some of these areas were military bases accessible only to United States personnel. Some tensions arose between the people of Panama and the U.S. citizens living in the Panama Canal Zone. This erupted in the January 9, 1964 events, known as Martyrs' Day.

In the late 1970s through the 1980s the city of Panama became an international banking center, bringing a lot of undesirable attention as an international money-laundering center. In 1989 after nearly a year of tension between the United States and Panama, President George H. Bush ordered the invasion of Panama to depose the leader of Panama, General Manuel Noriega. As a result of the action a portion of the El Chorrillo neighborhood, which consisted mostly of old wood-framed buildings dating back to the 1900s (though still a large slum area), was destroyed by fire. In 1999, the United States officially transferred control of the Panama Canal Zone to Panama, which remains in control today.[8] The city of Panama remains a banking center, although with very visible controls in the flow of cash. Shipping is handled through port facilities in the area of Balboa operated by the Hutchison Whampoa Company of Hong Kong and through several ports on the Caribbean side of the isthmus. Balboa, which is located within the greater Panama metropolitan area, was formerly part of the Panama Canal Zone, and in fact the administration of the former Panama Canal Zone was headquartered there.

Geography

Panamá is located between the Pacific Ocean and tropical rain forest in the northern part of Panama. The Parque Natural Metropolitano (Metropolitan Nature Park), stretching from Panama City along the Panama Canal, has unique bird species and other animals, such as tapir, puma, and caimans. At the Pacific entrance of the canal is the Centro de Exhibiciones Marinas (Marine Exhibitions Center), a research center for those interested in tropical marine life and ecology, managed by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Tropical forests around Panama are vital for the functioning of the Panama Canal, providing it with the water required for its operation. Due to the canal's importance to the Panamanian economy, tropical forests around the canal have been kept in an almost pristine state; the canal is thus a rare example of a vast engineering project in the middle of a forest that helped to preserve that forest. Along the western side of the canal is the Parque Nacional Soberanía (Sovereignty National Park), which includes the Summit botanical gardens and a zoo. The best known trail in this national park is Pipeline Road, popular among birdwatchers.[9]

Nearly 500 rivers lace Panama's rugged landscape. Most are unnavigable; many originate as swift highland streams, meander in valleys, and form coastal deltas. However, the Río Chepo and the Río Chagres, both within the boundaries of the city, work as sources of hydroelectric power.

The Río Chagres is one of the longest and most vital of the approximately 150 rivers that flow into the Caribbean. Part of this river was dammed to create Gatun Lake, which forms a major part of the transit route between the locks near each end of the canal. Both Gatun Lake and Madden Lake (also filled with water from the Río Chagres) provide hydroelectricity to the former Canal Zone area. The Río Chepo, another major source of hydroelectric power, is one of the more than 300 rivers emptying into the Pacific.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Panama City has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw), a little drier than a tropical monsoon climate. It sees 1,900 mm (74.8 in) of precipitation annually. The wet season spans from May through December, and the dry season spans from January through April. Temperatures remain constant throughout the year, averaging around 27 °C (81 °F). Sunshine is subdued in Panama because it lies in the Intertropical Convergence Zone, where there is a nearly continual cloud formation, even during the dry season.

| Climate data for Panama City (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 33.4 (92.1) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.8 (94.6) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.9 (93) |

33.9 (93) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.8 (92.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.5 (65.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.1 (70) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

20.0 (68) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 29.3 (1.154) |

10.1 (0.398) |

13.1 (0.516) |

64.7 (2.547) |

225.1 (8.862) |

235.0 (9.252) |

168.5 (6.634) |

219.9 (8.657) |

253.9 (9.996) |

330.7 (13.02) |

252.3 (9.933) |

104.6 (4.118) |

1,907.2 (75.087) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 4.9 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 17.0 | 20.0 | 16.0 | 7.5 | 131.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 228.9 | 245.2 | 183.9 | 173.1 | 108.5 | 116.3 | 106.1 | 118.1 | 99.2 | 103.9 | 139.8 | 120.5 | 1,743.5 |

| Source #1: World Meteorological Organization[10] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: ETESA (sunshine data recorded at Albrook Field)[11] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Architecture

Panama's old quarter (or Casco Viejo, Panama) features many architectural styles, from Spanish colonial buildings to French and Antillean townhouses built during the construction of the Panama Canal.[12] The more modern areas of the city have many high-rise buildings, which together form a very dense skyline. There are more than 110 high-rise projects under construction, with 127 already built.[13] The city holds the 45th place in the world by high-rise buildings count.[14]

The Centennial Bridge that crosses the Panama Canal earned the American Segmental Bridge Institute prize of excellence, along with seven other bridges in the Americas.[15]

Neighborhoods

The city is located in Panama District, although its metropolitan area also includes some populated areas on the opposite side of the Panama Canal. As in the rest of the country, the city is divided into corregimientos, in which there are many smaller boroughs. The old quarter, known as the Casco Viejo, is located in the corregimiento of San Felipe. San Felipe and twelve other corregimientos form the urban center of the city, including Santa Ana, El Chorrillo, Calidonia, Curundú, Ancón, Bella Vista, Bethania, San Francisco, Juan Diaz, Pueblo Nuevo, Parque Lefevre, and Río Abajo.

Economy

As the economic and financial center of the country, Panama City's economy is service-based, heavily weighted toward banking, commerce, and tourism.[16] The economy depends significantly on trade and shipping activities associated with the Panama Canal and port facilities located in Balboa. Panama's status as a convergence zone for capital from around the world due to the canal helped the city establish itself as a prime location for offshore banking and tax planning. Consequently, the economy has relied on accountants and lawyers who help global corporations navigate the regulatory landscape.[17] The city has benefited from significant economic growth in recent years, mainly due to the ongoing expansion of the Panama Canal, an increase in real estate investment, and a relatively stable banking sector.[18] There are around eighty banks in the city, at least fifteen of which are national.

Panama City is responsible for the production of approximately 55% of the country's GDP. This is because most Panamanian businesses and premises are located in the city and its metro area.[19] It is a stopover for other destinations in the country, as well as a transit point and tourist destination in itself.

Tourism is one of the most important economic activities in terms of revenue generation. This sector of the economy has seen a great deal of growth since the transfer of the Panama Canal Zone at the end of the twentieth century. The number of hotel rooms increased by more than ten-fold, from 1,400 in 1997 to more than 15,000 in 2013, while the number of annual visitors increased from 457,000 in 1999 to 1.4 million in 2011.[20] The city's hotel occupancy rate has always been relatively high, reaching the second highest for any city outside the United States in 2008, after Perth, Australia, and followed by Dubai.[21] However, hotel occupancy rates have dropped since 2009, probably due to the opening of many new luxury hotels.[22] Several international hotel chains, such as Le Méridien, Radisson, and RIU, have opened or plan to open new hotels in the city,[23] along with those previously operating under Marriott, Sheraton, InterContinental, and other foreign and local brands. Also, the Trump Organization is building the Trump Ocean Club, its first investment in Latin America,[24] and Hilton Worldwide recently opened its first Garden Inn Panama, at Eusebio A. Morales Avenue and 49A Street West, and more recently The Panamera, the second Waldorf Astoria Hotel in Latin America.[25]

Demographics

The city proper has approximately 880,691 inhabitants in 23 boroughs.[26] The inhabitants of Panama City are commonly referred to as capitalinos and include large numbers of Afro-Panamanians, mestizos, and mulattos, with notable white and Asian minorities.[27] There is a great deal of cultural diversity within the city, which manifests itself in the wide variety of languages commonly spoken, such as German, Portuguese, and English, in addition to Spanish.[20]

Culture

World Heritage Sites

Panamá Viejo

Panamá Viejo ("Old Panama")[28] is the name used for the architectural vestiges of the Monumental Historic Complex of the first Spanish city founded on the Pacific coast of the Americas by Pedro Arias de Avila on August 15, 1519. This city was the starting point for the expeditions that conquered the Inca Empire in Peru in 1532. It was a stopover point on one of the most important trade routes in the history of the American continent, leading to the famous fairs of Nombre de Dios and Portobelo, where most of the gold and silver that Spain took from the Americas passed through.[29]

Casco Viejo or Casco Antiguo

Built and settled in 1671 after the destruction of Panama Viejo by the privateer Henry Morgan, the historic district of Panama City (known as Casco Viejo, Casco Antiguo, or San Felipe) was conceived as a walled city to protect its settlers against future pirate attacks. It was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2003.[30]

Casco Antiguo displays a mix of architectural styles that reflect the country's cultural diversity: Caribbean, Republican, art deco, French, and colonial architecture mix in a site comprising around 800 buildings. Most of Panama City's main monuments are located in Casco Antiguo, including the Salón Bolivar, the National Theater (founded in 1908), Las Bóvedas, and Plaza de Francia. There are also many Catholic buildings, such as the Metropolitan Cathedral, the La Merced Church, and the St. Philip Neri Church. The distinctive golden altar at St. Joseph Church was one of the few items saved from Panama Viejo during the 1671 pirate siege. It was buried in mud during the siege and then secretly transported to its present location.

- The Cinta Costera 3 in Casco Viejo

Undergoing redevelopment, the old quarter has become one of the city's main tourist attractions, second only to the Panama Canal. Both government and private sectors are working on its restoration.[31] President Ricardo Martinelli built an extension to the Cinta Costera maritime highway viaduct in 2014 named "Cinta Costera 3" around the Casco Antiguo.[32]

Before the Cinta Costera 3 project was built there were protests. Much of the controversy surrounding the project involved the possibility that Casco Viejo would lose its World Heritage status. On June 28, 2012, UNESCO decided that Casco Viejo will not be put on the List of World Heritage Sites in Danger.

Literature

According to Professor Rodrigo Miró, the first story about Panama was written by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés and published as part of the Historia General y Natural de Las Indias in 1535. Some poets and novelists born in Panamá city are Manuel María Ayala (1785–1824), Amelia Denis de Icaza (1836–1911), Darío Herrera (1870–1914), Ricardo Miró (1883–1940), Gaspar Octavio Hernández (1893–1918), Demetrio Korsi (1899–1957), Ricardo Bermúdez (1914–2000), Joaquín Beleño (1922–88), Ernesto Endara (1932–), Diana Morán (1932–87), José Córdova (1937–), Pedro Rivera (1939–), Moravia Ochoa López (1941–), Roberto Fernández Iglesias (1941–), Jarl Ricardo Babot (1946–), Giovanna Benedetti (1949–), Manuel Orestes Nieto (1951–), Moisés Pascual (1955–), Héctor Miguel Collado (1960–), David Robinson Orobio (1960–), Katia Chiari (1969–), Carlos Oriel Wynter Melo (1971–), José Luis Rodríguez Pittí (1971–), and Sofía Santim (1982–).[33]

Art

One of the most important Panamanian artists is Alfredo Sinclair. He has worked for over 50 years in abstract art and has produced one of the most important artistic collections in the country. His daughter, Olga Sinclair, has also followed in his footsteps and has become another force in Panamanian art. Another very prominent Panamanian artist is Guillermo Trujillo, known worldwide for his abstract surrealism. Brooke Alfaro is Panamanian artist known throughout the world for his uniquely rendered oil paintings.

Tourism

Tourism in Panama City includes many different historic sites and locations related to the operation of the Panama Canal. A few of these sites are the following:

- Las Bóvedas ("The Vaults"), a waterfront promenade jutting out into the Pacific;

- The National Institute of Culture Building and the French embassy across from it;

- The Cathedral at Plaza de la Catedral;

- Teatro Nacional, an intimate performance center with outstanding natural acoustics and seating for about 800 guests;

- Museo del Canal Interoceánico (Interoceanic Canal Museum); and

- Palacio de las Garzas (Heron's Palace), the official name of the presidential palace, named for the numerous herons that inhabit the building.

- Miraflores Visitors Center at the Miraflores set of Locks on the Pacific Side, with a museum and a simulator of a ship cruising the canal.

In addition to these tourist attractions, Panama City offers many different options when it comes to hotel accommodations, including the first Waldorf Astoria hotel to open in Latin America, and many small boutique style hotels that have smaller numbers of guest rooms and offer a more intimate vacation. Nightlife in the city is centered around the Calle Uruguay and Casco Viejo neighborhoods. These neighborhoods contain a variety of different bars and nightclubs that cater to the tourists visiting the city.[34]

One of the newer tourist areas of the city is the area immediately east of the Pacific entrance of the canal, known as the Amador Causeway. This area is currently being developed as a tourist center and nightlife destination. The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute operates a station and a small museum open to the public at Culebra Point on the island of Naos. A new museum, the Biomuseo, was recently completed on the causeway in 2014. It was designed by the American architect Frank Gehry, famous for the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles.[35] Just outside the city limits is the Parque Municipal Summit.

The United States State Department does not recommend traveling outside of the city due to the lack of accessibility to some areas and the prevalence of organized crime. Within the city, the State Department acknowledges the presence of crimes in the city, some of which include violent acts such as shootings, rape, armed robbery, and intentional kidnapping. The United States State Department also warns tourists about the purchasing of counterfeited or pirated goods, as they may be in violation of local Panamanian laws. In terms of LGBTI rights in the city, same sex marriage is not recognized by the government but there are laws in place to prevent discrimination against the LGBTI community.[36]

- Plaza de la Independencia

Archway and classic calicanto wall in a traditional house

Archway and classic calicanto wall in a traditional house Compañía de Jesús, the ruins of an ancient convent of the Society of Jesus

Compañía de Jesús, the ruins of an ancient convent of the Society of Jesus

Sports

Throughout the 20th century, Panama City has excelled in boxing, baseball, basketball, and soccer. These sports have produced famous athletes such as Roberto Durán, Rommel Fernández, Rolando Blackman, Mariano Rivera, and Rod Carew. Today, these sports have clubs and associations that manage their development in the city. Panama Metro is the city's baseball team. There are boxing training centers in different gyms throughout the city's neighborhoods. There are also many football clubs, such as:

The city has four professional teams in the country's second level league, Liga Nacional de Ascenso:

- Atlético Nacional

- Deportivo Genesis

- Millenium

- Río Abajo

There are two main stadiums in Panama City, the National Baseball Stadium (also known as Rod Carew Stadium) and the Rommel Fernández Stadium, with capacities of 27,000 and 32,000 respectively. Additionally, the Roberto Durán Arena has a capacity of 18,000.

Rommel Fernández Soccer Stadium

Rommel Fernández Soccer Stadium Rod Carew National Baseball Stadium

Rod Carew National Baseball Stadium Roberto Durán Arena

Roberto Durán Arena

Education

The city has both public and private schools. Most of the private schools are at least bilingual. Higher education is headed by the two major public universities: the University of Panama and the Technological University of Panama. There are private universities, such as the Universidad Católica Santa María La Antigua, the Universidad Latina de Panama, the Universidad Latinoamericana de Ciencia y Tecnología (ULACIT), the Universidad Interamericana de Panama, the Distance and Open University of Panama (UNADP), Universidad del Istmo Panama, the Universidad Maritima Internacional de Panama, and the Universidad Especializada de las Americas. Also, there are Panama Branches of the Nova Southeastern University (its main campus is in Ft. Lauderdale in Broward County, Florida); the University of Oklahoma; the Central Texas University; the University of Louisville which runs a sister campus in the city,[37] and the Florida State University, which operates a broad curriculum program[38] in an academic and technological park known as Ciudad del Saber.

Healthcare

Panama City is home to at least 14 hospitals and an extensive network of public and private clinics, including the Hospital Santo Tomás, Hospital del Niño, Complejo Hospitalario Arnulfo Arias Madrid, Centro Médico Paitilla, Hospital Nacional, Clinica Hospital San Fernando, and Hospital Punta Pacifica.

About 45% of the country's physicians are located in Panama City.[39]

Hospital Santo Tomás, the largest public hospital in the country

Hospital Santo Tomás, the largest public hospital in the country Hospital Nacional, a full-service private hospital

Hospital Nacional, a full-service private hospital Instituto Oncológico Nacional, at former Gorgas Hospital

Instituto Oncológico Nacional, at former Gorgas Hospital

Transportation

Panama's international airport, Tocumen International Airport is located on the eastern outskirts of the city's metropolitan area. Panama City has a second international airport, Marcos A. Gelabert, located in an area once occupied by Albrook Air Force Base. Marcos A. Gelabert Airport is the main hub for AirPanama.

There are frequent traffic jams in Panama City due to the high levels of private transport ownership per kilometre of traffic lane. In an attempt to curb traffic jams, President Ricardo Martinelli has brought forward the citywide Panama Metro, initially 14 km (9 mi) long, stretching across the city.[40][41]

The bus terminal located in Ancon offers buses in and out of the city. Bus service is one of the most widely used forms of transportation in Panama. The terminal receives thousands of passengers daily from locations like David, Chiriqui, and the central provinces of Herrera and Los Santos. The terminal also receives international passengers from Central America via the Pan-American Highway.

Panama City offers transportation services through yellow taxis. Taxis do not use a meter to measure fares, instead using a zone system for fares that is published by the Autoridad de Transito y Transporte Terrestre, Panama's transit authority.

- The puente marino ("marine bridge"), Corredor Sur ("South Corridor")

Metrobus, the public bus system

Metrobus, the public bus system Taxi in Panama City

Taxi in Panama City Panama Metro, the metropolitan subway system

Panama Metro, the metropolitan subway system

Twin towns – Sister cities

Panama City is twinned with:[42][43]

Union of Ibero-American Capital Cities

Panama City is part of the Union of Ibero-American Capital Cities[50] from 12 October 1982 establishing brotherly relations with the following cities:

Andorra la Vella, Andorra

Andorra la Vella, Andorra Asunción, Paraguay

Asunción, Paraguay Bogotá, Colombia

Bogotá, Colombia Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires, Argentina Caracas, Venezuela

Caracas, Venezuela Guatemala City, Guatemala

Guatemala City, Guatemala Havana, Cuba

Havana, Cuba Quito, Ecuador

Quito, Ecuador La Paz, Bolivia

La Paz, Bolivia Lima, Peru

Lima, Peru Lisbon, Portugal

Lisbon, Portugal Madrid, Spain

Madrid, Spain Managua, Nicaragua

Managua, Nicaragua Mexico City, Mexico

Mexico City, Mexico Montevideo, Uruguay

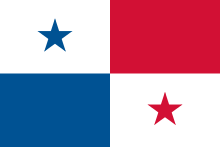

Montevideo, Uruguay Panama City, Panama

Panama City, Panama Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil San Jose, Costa Rica

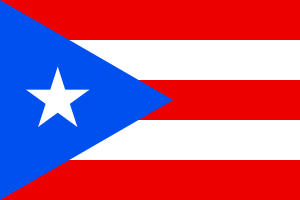

San Jose, Costa Rica San Juan, Puerto Rico

San Juan, Puerto Rico San Salvador, El Salvador

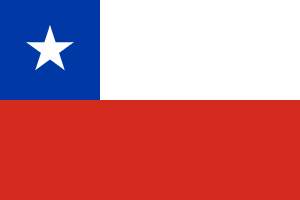

San Salvador, El Salvador Santiago, Chile

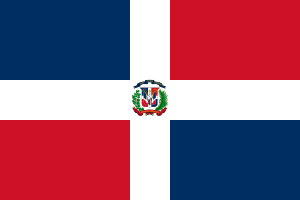

Santiago, Chile Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Tegucigalpa, Honduras

Tegucigalpa, Honduras

Gallery

Architecture in Casco Viejo (Old Quarter)

Architecture in Casco Viejo (Old Quarter) The belltower of the San Francisco de Asis Church.

The belltower of the San Francisco de Asis Church. Plaza Bolivar in Casco Viejo

Plaza Bolivar in Casco Viejo Ruins of the Old Panama

Ruins of the Old Panama Santa Ana Park

Santa Ana Park Causeway connecting Naos, Perico, and Flamenco Islands to the mainland

Causeway connecting Naos, Perico, and Flamenco Islands to the mainland The Bridge of the Americas, at the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal

The Bridge of the Americas, at the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal The Palace of the Herons, the official residence and office of the President of Panama

The Palace of the Herons, the official residence and office of the President of Panama Plaza de Francia, a square in honor of the workers and French engineers who participated in the construction of the Panama Canal.

Plaza de Francia, a square in honor of the workers and French engineers who participated in the construction of the Panama Canal. Skyline seen from Casco Viejo

Skyline seen from Casco Viejo The former Balboa Avenue

The former Balboa Avenue Panama skycrapers

Panama skycrapers- Panama Bay

View of part of the metropolitan area of Panama

View of part of the metropolitan area of Panama Panama City at night

Panama City at night Panama City at night

Panama City at night

See also

List of cities with the most skyscrapers

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 http://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/archivos/P3551P3551cuadro3-08.xls

- ↑ "Informe de Desarrollo Humano en Panamá" (in Spanish). 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ↑ Real Academia de la Lengua Española (October 2005). "Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. Apéndice 5: Lista de países y capitales, con sus gentilicios." (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Real Academia Española y Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española, «Lista de países y capitales, con sus gentilicios», Ortografía de la lengua española, Madrid, Espasa Panamá.1 País de América., p. 726, ISBN 978-84-670-3426-4,

GENT. panameño -ña. CAP. Panamá.

Panamá.2 Capital de Panamá. - ↑ "Investing in Panama". BussinesPanama.com. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ↑ www.lboro.ac.uk The World According to GaWC 2008 – Retrieved on 2010-10-10

- ↑ "Panama GDP - per capita (PPP) - Economy". Indexmundi.com. 2010-02-19. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- 1 2 "Panama Canal". History. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ "Canopy Tower, a famous birdwatchers hotel". Canopytower.com. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ↑ "World Weather Information Service - Panama City". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Datos Históricos : Estación Albrook Field" (in Spanish). Empresa de Transmision Electrica S.A. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ↑ "In Panama City's Old Quarter, a Rebirth Takes Place". Boston Globe. 2007-01-22. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- ↑ "Skyscraper page Panama City". Skyscraperpage.com. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ↑ "Skyscraper page Cities List". Skyscraperpage.com. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ↑ "La Prensa Newspaper". Mensual.prensa.com. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ↑ "Panama Useful Facts". Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk (April 6, 2016). "Panama Papers Leak Casts Light on a Law Firm Founded on Secrecy". New York Times. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Panama economy grew 2.4 percent in 2009". Reuters. 2010-03-02. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "Municipio de Panamá". Municipio.gob.pa. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- 1 2 Neville, Tim (May 3, 2013). "Panama City Rising". New York Times. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Panama City Has The Second Highest Hotel Occupancy Outside Of The United States". 2008-05-06. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "Hotel occupancy rates see sharp drop.". 2009-10-21. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "Twenty-two Hotels are Under Construction in Panama.". Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "Donald J. Trump Launches His First Luxury Development in Panama". 2006-04-26. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "Waldorf Astoria Hotels & Resorts Expands into Latin America with opening of Waldorf Astoria Panama". 2013-03-18. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ↑ "Panama City Hall" (Spanish) Archived October 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Panama". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Panama Viejo". Patronato Panama Viejo. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ↑ "UNESCO Official Site". Whc.unesco.org. 1997-12-07. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ↑ "Archaeological Site of Panamá Viejo and Historic District of Panamá". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Panama Casco Viejo Blog – Panama News: World Bank invests in Cultural Industries for Casco Antiguo". Arcoproperties.com. 2008-09-11. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ↑ Cinta Costera

- ↑ Panamanian literature

- ↑ CNN, By Gabriel O'Rorke, for. "Live large, pay small in Panama City - CNN.com". CNN. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ↑ Biodiversity Museum

- ↑ "Panama". travel.state.gov. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ↑ "Channing Slate's Homepage". Web.archive.org. 2008-01-08. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ↑ "FSU-Panama Homepage". Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "Panama City Hall information on education and". Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "El Metro de Panamá". Secretaría del Metro. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Metrobus Panama". Metrobus Panama. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 List of sister cities in Panama from Sister Cities International

- 1 2 3 "Panama - Fort Lauderdale and Miami on Sister Cities.com". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sister Cities, Public Relations". Guadalajara municipal government. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Incheon Sister Cities". Incheon Metropolitan City. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ http://focustaiwan.tw/news/aipl/201609050035.aspx

- ↑ Sister city list (.DOC)

- ↑ "Taipei City Council". Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ↑ "Panama City and Tel Aviv Sign Agreement to Become Sister Cities". Caribbean Journal. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ "Declaración de Hermanamiento múltiple y solidario de todas las Capitales de Iberoamérica (12-10-82)" (PDF). 12 October 1982. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

Bibliography

- Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390.

- Mellander, Gustavo A. (1971). The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Danville, Ill.: Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568.

Further reading

- David F. Marley (2005), "Panama City", Historic Cities of the Americas, 2, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, p. 347+, ISBN 1576070271

External links

Coordinates: 8°59′N 79°31′W / 8.983°N 79.517°W