Jazz fusion

| Jazz fusion | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Late 1960s United States |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms | |

| Other topics | |

Jazz fusion (also known as jazz-rock, fusion jazz or just simply fusion)[1] is a musical genre that developed in the late 1960s when musicians combined aspects of jazz harmony and improvisation with styles such as funk, rock, rhythm and blues, and Latin jazz. During this time many jazz musicians began experimenting with electric instruments and amplified sound for the first time, as well as electronic effects and synthesizers. Many of the developments during the late 1960s and early 1970s have since become established elements of jazz fusion musical practice.

Fusion arrangements vary in complexity—some employ groove-based vamps fixed to a single key, or even a single chord, with a simple melodic motif (a lick). Others can feature odd or shifting time signatures with elaborate chord progressions, melodies, and counter-melodies. Typically, these arrangements, whether simple or complex, will feature extended improvised sections that can vary in length. As with jazz, fusion often employs brass instruments such as trumpet and saxophone as melody and soloing instruments but other instruments often substitute for these. The rhythm section typically consists of electric bass (in some cases fretless), electric guitar, electric piano/synthesizer (in contrast to the double bass and piano used in earlier jazz) and drums. As with traditional jazz improvisation, fusion instrumentalists generally require a high level of technical proficiency.

The term "jazz-rock" is often used as a synonym for "jazz fusion" as well as for music performed by late 1960s and 1970s-era rock bands that added jazz elements to their music. After a decade of popularity during the 1970s, fusion expanded its improvisatory and experimental approaches through the 1980s, in parallel with the development of a radio-friendly style called smooth jazz. Experimentation continued in the 1990s and 2000s. Fusion albums, even those that are made by the same group or artist, may include a variety of musical styles. Rather than being a codified musical style, fusion can be viewed as a musical tradition or approach.

History

Precursors

Afro-Cuban jazz, one the earliest form of Latin jazz, is a fusion of Afro-Cuban clave-based rhythms with jazz harmonies and techniques of improvisation. Afro-Cuban jazz first emerged in the early 1940s with the Cuban musicians Mario Bauza and Frank Grillo "Machito" in the band Machito and his Afro-Cubans, based in New York City. In 1947 the collaborations of bebop innovator Dizzy Gillespie with Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo brought Afro-Cuban rhythms and instruments, most notably the congas and the bongos into the East Coast jazz scene. Early combinations of jazz with Cuban music, such as Dizzy's and Pozo's "Manteca" and Charlie Parker's and Machito's "Mangó Mangüé", were commonly referred to as "Cubop", short for Cuban bebop.[2] During its first decades, the Afro-Cuban jazz movement was stronger in the United States than in Cuba itself.[3]

1960s

Allmusic Guide states that "until around 1967, the worlds of jazz and rock were nearly completely separate".[4] While in the United States modern jazz and electric R&B may have represented opposite poles of blues-based Afro-American music, the British pop music of the beat boom developed out of the skiffle and R&B championed by well-known jazzmen such as Chris Barber. English fusion guitarist John McLaughlin, for example, had played what Allmusic describes as a "blend of jazz and American R&B" with Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames[5] as early as 1962 and continued with The Graham Bond Organisation (with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker) whose style Allmusic calls "rhythm & blues with a strong jazzy flavor".[6] Bond himself had begun playing straight jazz with Don Rendell, while Manfred Mann, who recorded a Cannonball Adderley tune on their first album, when joined by Bruce turned out the 1966 EP record Instrumental Asylum, which undoubtedly fused jazz and rock.[7] One of the earliest releases from Pink Floyd, London '66–'67 incorporated jazz-influenced improvisation to their psychedelic compositions.

Nevertheless, these developments made little impact in the United States. Jazz vibraphonist Gary Burton was an "innovator" in the 1960s. In 1967, Burton worked with electric guitarist Larry Coryell and recorded Duster, which is considered one of the first fusion records.[8] Texas-born guitarist Coryell was also a pioneer of electric jazz in the same era.[9] Trumpeter and composer Miles Davis had a major influence on the development of jazz fusion with his 1968 album Miles in the Sky. It is the first of Davis' albums to incorporate electric instruments, with Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter playing electric piano and bass guitar, respectively. Davis furthered his explorations into the use of electric instruments on another 1968 album, Filles de Kilimanjaro, with pianist Chick Corea and bassist Dave Holland.

Davis' 1969 album In a Silent Way is considered his first fusion album.[10] Composed of two side-long improvised suites edited heavily by record producer Teo Macero, this quiet, static album would be equally influential upon the development of ambient music. It featured contributions from musicians who would all go on to spread the fusion evangel with their own groups in the 1970s: Wayne Shorter, Hancock, Corea, pianist Josef Zawinul, John McLaughlin, Holland, and drummer Tony Williams, who quit Davis to form The Tony Williams Lifetime with McLaughlin and jazz organist Larry Young. Their debut record Emergency! of that year is also cited as one of the early acclaimed fusion albums.

Jazz-rock

| Jazz rock | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Late 1960s United States |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms | |

| Other topics | |

The term "jazz-rock" (or "jazz/rock") is often used as a synonym for the term "jazz fusion". However, some make a distinction between the two terms. The Free Spirits have sometimes been cited as the earliest jazz-rock band.[11] During the late 1960s, at the same time that jazz musicians were experimenting with rock rhythms and electric instruments, rock groups such as Cream, the Grateful Dead and The Doors were "beginning to incorporate elements of jazz into their music" by "experimenting with extended free-form improvisation". Other "groups such as Blood, Sweat & Tears directly borrowed harmonic, melodic, rhythmic and instrumentational elements from the jazz tradition".[12]

.png)

The rock groups that drew on jazz ideas (like Soft Machine, Colosseum, Caravan, Chicago, Spirit and Frank Zappa) turned the blend of the two styles with electric instruments.[13] Davis' fusion jazz was "pure melody and tonal color",[13] while Frank Zappa's music was more "complex" and "unpredictable".[14] Zappa released the solo album Hot Rats in 1969[15][16] and had a major jazz influence mainly consisting of long instrumental pieces.[16][17] Zappa released two LPs in 1972 which were also very jazz-oriented, called The Grand Wazoo and Waka/Jawaka. Prolific jazz artists such as George Duke and Aynsley Dunbar played on these LPs.

AllMusic states that the term jazz-rock "may refer to the loudest, wildest, most electrified fusion bands from the jazz camp, but most often it describes performers coming from the rock side of the equation." The guide states that "jazz-rock first emerged during the late '60s as an attempt to fuse the visceral power of rock with the musical complexity and improvisational fireworks of jazz. Since rock often emphasized directness and simplicity over virtuosity, jazz-rock generally grew out of the most artistically ambitious rock subgenres of the late '60s and early '70s: psychedelia, progressive rock, and the singer/songwriter movement."[18]

According to jazz writer Stuart Nicholson, jazz-rock paralleled free jazz in how it was "on the verge of creating a whole new musical language in the 1960s". He said the albums Emergency! (1970) by the Tony Williams Lifetime and Agharta (1975) by Miles Davis "suggested the potential of evolving into something that might eventually define itself as a wholly independent genre quite apart from the sound and conventions of anything that had gone before." This development was stifled by commercialism, Nicholson said, as the genre "mutated into a peculiar species of jazz-inflected pop music that eventually took up residence on FM radio" at the end of the 1970s.[19]

1970s

|

"Go Ahead John"

Recorded on March 7, 1970, "Go Ahead John" is an out-take from Miles Davis's Jack Johnson sessions.[20] It features on the 1974 release Big Fun. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Davis' Bitches Brew sessions, recorded in August 1969 and released the following year, mostly abandoned jazz's usual swing beat in favor of a rock-style backbeat anchored by electric bass grooves. The recording "…mixed free jazz blowing by a large ensemble with electronic keyboards and guitar, plus a dense mix of percussion."[21] Davis also drew on the rock influence by playing his trumpet through electronic effects and pedals. While the album gave Davis a gold record, the use of electric instruments and rock beats created a great deal of consternation amongst some more conservative jazz critics. During the 1970s, many of these critics in the jazz community perceived jazz music "as high art in contrast with the more commercial and less sophisticated rock music"[22] with which it was being fused. Racial identity was also an essential component of genre conventions, and jazz critics often censured black musicians who deserted the purity of the jazz experience for the white world of rock music. Although Davis was originally denounced by purists, many credit Davis and records such as "Bitches Brew" with paving the way for the fusion movement.

Davis also proved to be an able talent-spotter; much of 1970s fusion was performed by bands started by alumni from Davis' ensembles, including The Tony Williams Lifetime, Weather Report, The Mahavishnu Orchestra, Return to Forever, and Herbie Hancock's funk-infused Headhunters band. In addition to Davis and the musicians who worked with him, additional important figures in early fusion were Larry Coryell and Billy Cobham, with his album Spectrum. Herbie Hancock first continued the path of Miles Davis with his experimental fusion albums, such as Crossings in 1972, but soon after that he became an important developer of "jazz-funk" with his seminal albums Head Hunters in 1973 and Thrust in 1974. Later in the 1970s and early 1980s Hancock took a more commercial approach. Hancock was one of the first jazz musicians to use synthesizers.

At its inception, Weather Report was an avant-garde experimental jazz group, following in the steps of In a Silent Way. The band received considerable attention for its early albums and live performances, which featured pieces that might last up to 30 minutes. The band later introduced a more commercial sound, which can be heard in Joe Zawinul's hit song "Birdland" (1977). Weather Report's albums were also influenced by different styles of Latin, African, and European music, offering an early world music fusion variation. Jaco Pastorius, an innovative fretless electric bass player, joined the group in 1976 on the album Black Market, was co-producer (with Zawinul) on 1977's Heavy Weather, and is prominently featured on the 1979 live recording 8:30. Heavy Weather is the top-selling album of the genre.

In England, the jazz fusion movement was headed by Nucleus, led by Ian Carr, and whose key players Karl Jenkins and John Marshall both later joined the seminal jazz rock band Soft Machine, leaders of what became known as the Canterbury scene. Their best-selling recording, Third (1970), was a double album featuring one track per side in the style of the aforementioned recordings of Miles Davis. A prominent English band in the jazz-rock style of Blood, Sweat & Tears and Chicago was If, who released a total of seven records in the 1970s.

Chick Corea formed his band Return to Forever in 1972. The band started with Latin-influenced music (including Brazilians Flora Purim as vocalist and Airto Moreira on percussion), but was transformed in 1973 to become a jazz-rock group that took influences from both psychedelic and progressive rock. The new drummer was Lenny White, who had also played with Miles Davis. Return to Forever's songs were distinctively melodic due to the Corea's composing style and the bass playing style of Stanley Clarke, who is often regarded with Pastorius as one of the most influential electric bassists of the 1970s. Guitarist Bill Connors joined Corea's band in 1973 but soon left for his acoustic solo project. He was replaced by guitarist Al Di Meola, who became an important fusion guitarist as well.

John McLaughlin formed a fusion band, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, with drummer Billy Cobham, violinist Jerry Goodman, bassist Rick Laird and keyboardist Jan Hammer. The band released their first album, The Inner Mounting Flame, in 1971. Hammer pioneered the use of the Minimoog synthesizer with distortion effects and, with his mastery of the pitch bend wheel, made it sound very much like an electric guitar. The sound of the Mahavishnu Orchestra was influenced by both psychedelic rock and Indian classical sounds.

The band's first lineup split after two studio albums and one live album, but McLaughlin formed another group under the same name which included Jean-Luc Ponty, a jazz violinist who also made a number of important fusion recordings under his own name as well as with Frank Zappa, drummer Narada Michael Walden, keyboardist Gayle Moran, and bassist Ralph Armstrong. McLaughlin also worked with Latin-rock guitarist Carlos Santana in the early 1970s.

Initially Santana's San Francisco-based band blended Latin salsa, rock, blues, and jazz, featuring Santana's clean guitar lines set against Latin instrumentation such as timbales and congas. But in their second incarnation, heavy fusion influences had become central to the 1972–1976 sound. These can be heard in Santana's use of extended improvised solos and in the harmonic voicings of Tom Coster's keyboard playing on some of the groups' mid-1970s recordings. In 1973 Santana recorded a nearly two-hour live album of mostly instrumental, jazz-fusion music, Lotus, which was only released in Europe and Japan for more than twenty years.

Other influential musicians during the 1970s include fusion guitarist Larry Coryell with his band The Eleventh House and electric guitarist Pat Metheny. The Pat Metheny Group, which was founded in 1977, made both the jazz and pop charts with their second album, American Garage (1980). Although jazz performers criticized the fusion movement's use of rock styles and electric and electronic instruments, even seasoned jazz veterans like Buddy Rich, Maynard Ferguson and Dexter Gordon eventually modified their music to include fusion elements. The late 1970s saw the emergence of the Steve Morse-led fusion band, the Dixie Dregs. This band fused the sounds of rock, jazz, country, funk, classical, bluegrass and Celtic.

The influence of jazz fusion did not only affect the US and Europe. The genre was very influential in Japan in the late 1970s, eventually leading to the formation of bands such as Casiopea and T-Square. T-Square's song "Truth" would later become the theme for Japan's Formula One racing events.

1980s

Smooth jazz

By the early 1980s, much of the original fusion genre was subsumed into other branches of jazz and rock, especially smooth jazz, a radio-friendly subgenre of fusion which is influenced stylistically by R&B, funk and pop.[23] Smooth jazz can be traced to at least the late 1960s, when producer Creed Taylor worked with guitarist Wes Montgomery on three popular music-oriented records. Taylor founded CTI Records and many established jazz performers recorded for CTI, including Freddie Hubbard, Chet Baker, George Benson and Stanley Turrentine. The records recorded under Taylor's guidance were typically aimed as much at pop audiences as at jazz fans.

In the mid- to late-1970s, smooth jazz became established as a commercially viable genre. It was pioneered by such artists as Lee Ritenour, Larry Carlton, Grover Washington, Jr., Spyro Gyra (with songs such as "Morning Dance"), George Benson, Chuck Mangione, Sérgio Mendes, David Sanborn, Tom Scott, Dave and Don Grusin, Bob James and Joe Sample.

.jpg)

The merging of jazz and pop/rock music took a more commercial direction in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in the form of compositions with a softer sound palette that could fit comfortably in a soft rock radio playlist. The AllMusic guide's article on fusion states that "unfortunately, as it became a money-maker and as rock declined artistically from the mid-'70s on, much of what was labeled fusion was actually a combination of jazz with easy-listening pop music and lightweight R&B."[24]

Artists such as Al Jarreau, Kenny G, Ritenour, James and Sanborn among others were leading purveyors of this pop-oriented mixture (also known as "west coast" or "AOR fusion"). This genre is most frequently called "smooth jazz" and is not considered "true fusion" among the listeners of both mainstream jazz and jazz fusion, who find it too rarely contains the improvisational, melodic or harmoic qualities that originally surfaced in jazz decades earlier, deferring to a more commercially viable sound more widely enabled for commercial radio airplay in the United States.

Michael and Randy Brecker produced funk-influenced jazz with soloists.[25] Saxophonist David Sanborn was considered a "soulful" and "influential" voice.[25] However, Kenny G was criticized by both fusion and jazz fans, and some musicians, while having become a huge commercial success. Music reviewer George Graham argues that the "so-called 'smooth jazz' sound of people like Kenny G has none of the fire and creativity that marked the best of the fusion scene during its heyday in the 1970s."[26]

Other styles

Although the meaning of "fusion" became confused with the advent of "smooth jazz", a number of groups helped to revive the jazz fusion genre beginning in the mid-to-late 1980s. In the 1980s, a critic argued that "…the promise of fusion went unfulfilled to an extent, although it continued to exist in groups such as Jeff Lorber, Yellowjackets, Tribal Tech and Chick Corea's Elektric Band".[24] Many of the most well-known fusion artists were members of earlier jazz fusion groups, and some of the fusion "giants" of the 1970s kept working in the genre.

Miles Davis continued his career after having a lengthy break in the late 1970s. He recorded and performed fusion throughout the 1980s with new young musicians and continued to ignore criticism from fans of his older mainstream jazz. While Davis' works of the 1980s remain controversial, his recordings from that period have the respect of many fusion and other listeners. In 1985 Chick Corea formed a new fusion band called the Chick Corea Elektric Band, featuring young musicians such as drummer Dave Weckl and bassist John Patitucci, as well as guitarist Frank Gambale and saxophonist Eric Marienthal.

Acid jazz, nu jazz and jazz rap

Acid jazz developed in the UK in the 1980s and 1990s, influenced by jazz-funk and electronic music. Acid jazz often contains various types of electronic composition (sometimes including sampling or a live DJ cutting and scratching), but it is just as likely to be played live by musicians, who often showcase jazz interpretation as part of their performance. Jazz-funk musicians such as Roy Ayers and Donald Byrd are often credited as the forerunners of acid jazz.[27]

Nu jazz is influenced by jazz harmony and melodies, and there are usually no improvisational aspects. It can be very experimental in nature and can vary widely in sound and concept. It ranges from the combination of live instrumentation with the beats of jazz house (as exemplified by St Germain, Jazzanova and Fila Brazillia) to more band-based improvised jazz with electronic elements (for example The Cinematic Orchestra, Kobol and the Norwegian "future jazz" style pioneered by Bugge Wesseltoft, Jaga Jazzist and Nils Petter Molvær).

Jazz rap developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and incorporates jazz influences into hip hop. In 1988, Gang Starr released the debut single "Words I Manifest", which sampled Dizzy Gillespie's 1962 "Night in Tunisia", and Stetsasonic released "Talkin' All That Jazz", which sampled Lonnie Liston Smith. Gang Starr's debut LP No More Mr. Nice Guy (1989) and their 1990 track "Jazz Thing" sampled Charlie Parker and Ramsey Lewis. The groups which made up the Native Tongues Posse tended towards jazzy releases: these include the Jungle Brothers' debut Straight Out the Jungle (1988), and A Tribe Called Quest's People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm (1990) and The Low End Theory (1991). Rap duo Pete Rock & CL Smooth incorporated jazz influences on their 1992 debut Mecca and the Soul Brother. Rapper Guru's Jazzmatazz series began in 1993, using jazz musicians during the studio recordings.

Though jazz rap had achieved little mainstream success, Miles Davis' final album Doo-Bop (released posthumously in 1992) was based around hip hop beats and collaborations with producer Easy Mo Bee. Davis' ex-bandmate Herbie Hancock also absorbed hip-hop influences in the mid-1990s, releasing the album Dis Is Da Drum in 1994.

Punk jazz and jazzcore

The relaxation of orthodoxy which was concurrent with post-punk in London and New York City led to a new appreciation of jazz. In London, the Pop Group began to mix free jazz and dub reggae into their brand of punk rock.[28] In New York, No Wave took direct inspiration from both free jazz and punk. Examples of this style include Lydia Lunch's Queen of Siam,[29] Gray, the work of James Chance and the Contortions (who mixed soul music with free jazz and punk rock)[29] and the Lounge Lizards[29] (the first group to call themselves "punk jazz)."

John Zorn took note of the emphasis on speed and dissonance that was becoming prevalent in punk rock, and incorporated this into free jazz with the release of the Spy vs Spy album in 1986, a collection of Ornette Coleman tunes done in the contemporary thrashcore style.[30] In the same year, Sonny Sharrock, Peter Brötzmann, Bill Laswell and Ronald Shannon Jackson recorded the first album under the name Last Exit (free jazz band), a similarly aggressive blend of thrash and free jazz.[31] These developments are the origins of jazzcore, the fusion of free jazz with hardcore punk.

M-Base

M-Base (short for "macro-basic array of structured extemporization") centers around a movement started in the 1980s. It was initially a loose collective of young African-American musicians in New York which included Steve Coleman, Greg Osby and Gary Thomas developing a complex but grooving[32] sound.

In the 1990s most M-Base participants turned to more conventional music, but Coleman, the most active participant, continued developing his music in accordance with the M-Base concept.[33] Coleman's audience decreased, but his music and concepts influenced many musicians,[34] both in terms of music technique[35] and of the music's meaning.[36] Hence, M-Base changed from a movement of a loose collective of young musicians to a kind of informal Coleman "school",[37] with a much advanced but already originally implied concept.[38] Steve Coleman's music and M-Base concept gained recognition as "next logical step" after Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman.[39]

1990s–2000s

Joe Zawinul's fusion band, The Zawinul Syndicate, began adding more elements of world music during the 1990s. One of the notable bands that became prominent in the early 1990s is Tribal Tech, led by guitarist Scott Henderson and bassist Gary Willis. Henderson was a member of both Corea's and Zawinul's ensembles in the late 1980s while putting together his own group. Tribal Tech's most common lineup also includes keyboardist Scott Kinsey and drummer Kirk Covington; Willis and Kinsey have both recorded solo fusion projects. Henderson has also been featured on fusion projects by drummer Steve Smith of Vital Information which also include bassist Victor Wooten of the eclectic Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, recording under the banner Vital Tech Tones.

Allan Holdsworth is a guitarist who performs in jazz, fusion, and rock styles. Other guitarists such as Eddie Van Halen, Steve Vai and Yngwie Malmsteen have praised his fusion playing. He often used a SynthAxe guitar synthesizer in his recordings of the late 1980s, which he credits for expanding his composing and playing options. Holdsworth has continued to release fusion recordings and tour worldwide. Another former Soft Machine guitarist, Andy Summers of The Police, released several fusion albums in the early 1990s.

Guitarists John Scofield and Bill Frisell have both made fusion recordings over the past two decades while also exploring other musical styles. Scofield's Pick Hits Live and Still Warm are fusion examples, while Frisell has maintained a unique approach in drawing heavy influences from traditional music of the United States. Japanese fusion guitarist Kazumi Watanabe released numerous fusion albums throughout the 1980s and 1990s, highlighted by his works such as Mobo Splash and Spice of Life.

Brett Garsed and T. J. Helmerich are also watched as prominent fusion guitar players, having released several albums together since the beginning of the 1990s (Quid Pro Quo (1992), Exempt (1994), Under the Lash of Gravity (1999), Uncle Moe's Space Ranch (2001), Moe's Town (2007)) and collaborating in many other projects or releasing solo albums (Brett Garsed – Big Sky) all them falling in the genre.

The saxophonist Bob Berg, who originally came to prominence as a member of Miles Davis's bands, recorded a number of fusion albums with fellow Miles band member and guitarist Mike Stern. Stern continues to play fusion regularly in New York City and worldwide. They often teamed with the world-renowned drummer Dennis Chambers, who has also recorded his own fusion albums. Chambers is also a member of CAB, led by bassist Bunny Brunel and featuring the guitar and keyboard of Tony MacAlpine. CAB 2 garnered a Grammy nomination in 2002. MacAlpine has also served as guitarist of the metal fusion group Planet X, featuring keyboardist Derek Sherinian and drummer Virgil Donati. Another former member of Miles Davis's bands of the 1980s that has released a number of fusion recordings is saxophonist Bill Evans, highlighted by 1992's Petite Blonde.

Fusion shred guitar player and session musician Greg Howe has released solo albums such as Introspection (1993), Uncertain Terms (1994), Parallax (1995), Five (1996), Ascend (1999), Hyperacuity (2000), Extraction (2003) with electric bassist Victor Wooten and drummer Dennis Chambers, and Sound Proof (2008). Howe combines elements of rock, blues and Latin music with jazz influences using a technical, yet melodic guitar style. Ex-Dream Theater drummer Mike Portnoy formed the band Liquid Tension Experiment with guitarist John Petrucci, keyboardist Jordan Rudess and bass guitarist Tony Levin. Their style blended the complex rhythms of jazz fusion and progressive rock along with the heavy sound of progressive metal.

Drummer Jack DeJohnette's Parallel Realities band featuring fellow Miles' alumni Dave Holland and Herbie Hancock, along with Pat Metheny, recorded and toured in 1990, highlighted by a DVD of a live performance at the Mellon Jazz Festival in Philadelphia. Jazz bassist Christian McBride released two fusion recordings drawing from the jazz-funk idiom in Sci-Fi (2000) and Vertical Vision (2003). Other significant recent fusion releases have come from keyboardist Mitchel Forman and his band Metro, former Mahavishnu bassist Jonas Hellborg with the late guitar virtuoso Shawn Lane, keyboardist Tom Coster, and Marbin with their unique blend of jazz, rock, blues, gospel, and Israeli folk music.

Influence on rock music

According to bassist/singer Randy Jackson, jazz fusion is an exceedingly difficult genre to play; "I … picked jazz fusion because I was trying to become the ultimate technical musician-able to play anything. Jazz fusion to me is the hardest music to play. You have to be so proficient on your instrument. Playing five tempos at the same time, for instance. I wanted to try the toughest music because I knew if I could do that, I could do anything."[40]

Jazz-rock fusion's technically challenging guitar solos, bass solos and odd metered, syncopated drumming started to be incorporated in the technically focused progressive metal genre in the early 1990s. Progressive rock, with its affinity for long solos, diverse influences, non-standard time signatures and complex music had very similar musical values as jazz fusion. Some prominent examples of progressive rock mixed with elements of fusion is the music of Gong, Ozric Tentacles and Emerson, Lake & Palmer.

The death metal band Atheist produced albums Unquestionable Presence in 1991 and Elements in 1993 containing heavily syncopated drumming, changing time signatures, instrumental parts, acoustic interludes, and Latin rhythms. Meshuggah first attracted international attention with the 1995 release Destroy Erase Improve for its fusion of fast-tempo death metal, thrash metal and progressive metal with jazz fusion elements. Cynic recorded a complex, unorthodox form of jazz-fusion-influenced experimental death metal with their 1993 album Focus. In 1997, G.I.T. guitarist Jennifer Batten under the name of Jennifer Batten's Tribal Rage: Momentum released Momentum – an instrumental hybrid of rock, fusion and exotic sounds. Mudvayne is heavily influenced by jazz, especially in bassist Ryan Martinie's playing.[41][42] Puya frequently incorporates influences from American and Latin jazz music.[43]

Another, more cerebral, all-instrumental progressive jazz fusion-metal band Planet X released Universe in 2000 with Tony MacAlpine, Derek Sherinian (ex-Dream Theater) and Virgil Donati (who has played with Scott Henderson from Tribal Tech). The band blends fusion-style guitar solos and syncopated odd-metered drumming with the heaviness of metal. Tech-prog-fusion metal band Aghora formed in 1995 and released their first album, self-titled Aghora, recorded in 1999 with Sean Malone and Sean Reinert, both former members of Cynic. Gordian Knot, another Cynic-linked experimental progressive metal band, released its debut album in 1999 which explored a range of styles from jazz-fusion to metal. The Mars Volta is extremely influenced by jazz fusion, using progressive, unexpected turns in the drum patterns and instrumental lines. The style of Uzbek prog band Fromuz is described as "prog fusion". In lengthy instrumental jams, the band transitions from fusion of rock and ambient world music to jazz and progressive hard rock tones.[44]

Influential recordings

Albums from the late 1960s and early 1970s include Miles Davis' ambient-sounding In a Silent Way (1969) and his rock-infused Bitches Brew (1970). Davis' A Tribute to Jack Johnson (1971) has been cited as "the purest electric jazz record ever made" and "one of the most remarkable jazz-rock discs of the era".[20][45] Davis's album On the Corner (1972), at the time of release one of his most reviled, has since been viewed as having "set the precedent for a whole subspecies of DJ culture." [46] Throughout the 1970s, Weather Report released albums ranging from its 1971 self-titled disc Weather Report (1971) (which continued the style of Miles Davis album Bitches Brew) to 1979's 8:30. Chick Corea's Latin-oriented fusion band Return to Forever released influential albums such as 1973's Light as a Feather. In that same year, Herbie Hancock's Head Hunters infused jazz-rock fusion with a heavy dose of Sly and the Family Stone-style funk. Virtuoso performer-composers played an important role in the 1970s. In 1976, fretless bassist Jaco Pastorius released Jaco Pastorius; electric and double bass player Stanley Clarke released School Days; and keyboardist Chick Corea released his Latin-infused My Spanish Heart, which received a five-star review from Down Beat magazine.

In the 1980s, Chick Corea produced well-regarded albums, including The Chick Corea Elektric Band (1986), Light Years (1987), and Eye of the Beholder (1988). In the early 1990s, Tribal Tech produced two albums, Tribal Tech (1991) and Reality Check (1995). Canadian bassist-composer Alain Caron released his album Rhythm 'n Jazz in 1995. Mike Stern released Give and Take in 1997.

Jazz fusion record labels

In the last 20 years there have been some important record labels which have specialized in jazz-fusion as well as jazz. Some of them include ESC Records,[47] Tone Center on Shrapnel Records,[48] Favoured Nations, AbstractLogix,[49] Heads Up International,[50] Mack Avenue Records,[51] and Buckyball Music.[52] Due to the small market for instrumental music such as jazz-fusion, artists often release music under their own label or under subdivisions of larger record companies. Some examples include Chick Corea/Ron Moss' [53] Stretch Records [54] under the Concord Music Group, Dave Grusin and Larry Rosen (producer) Grusin/Rosen's GRP Records through Verve Music Group, Carl Filipiak's Geometric Records,[55] Merck's Alex Merck Music GmbH,[56] Frank Gambale's Wombat Records,[57] Anders Johansson/Jens Johansson's Heptagon Records [58] and Richard Hallebeek's Richie Rich Music [59] to name a few. Other solo fusion artists release and promote their own music under their own names such as Allen Hinds, Frans Vollink, Bernhard Lackner, Doug Johns and Geraldo Henrique Bulhões.[60]

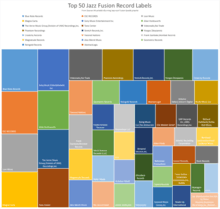

According to Steven's Muschalik's analysis of his Burning Jazz-fusion playlist these are the top 50 jazz-fusion labels from 1995-2015.

See also

References

- ↑ Garry, Jane (2005). "Jazz". In Haynes, Gerald D. Encyclopedia of African American Society. SAGE Publications. p. 465.

- ↑ Fernandez, Raul A. (2006). From Afro-Cuban rhythms to Latin jazz. University of California Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780520939448. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ↑ Acosta, Leonardo (2003: 59). Cubano be, cubano bop: one hundred years of jazz in Cuba. Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 158834147X

- ↑ http://www.allmusic.com/explore/style/d299

- ↑ Georgie Fame | AllMusic

- ↑ Graham Bond | AllMusic

- ↑ Manfred Mann | AllMusic

- ↑ S.E. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Jazz (Backbeat Books, 2002). ISBN 087930717X. Pages 180-181

- ↑ D. Dicaire, Jazz Musicians, 1945 to the Present (McFarland, 2006), ISBN 0786420979, p. 213

- ↑ Southall, Nick. Review: In a Silent Way. Stylus Magazine. Retrieved on 2010-04-01.

- ↑ Unterberger 1998, pg. 329

- ↑ The Jazz/Rock Fusion Page: A site dedicated to jazz fusion and related genres with a special emphasis on jazz/rock fusion

- 1 2 N. Tesser, The Playboy Guide to Jazz (Plume, 1998), ISBN 0452276489, p. 178

- ↑ S.E. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Jazz (Backbeat Books, 2002). ISBN 087930717X. p.178

- ↑ Huey, Steve, Hot Rats. Review, Allmusic.com. Retrieved on January 2, 2008.

- 1 2 Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 194.

- ↑ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 74.

- ↑ http://www.allmusic.com/explore/style/d2776

- ↑ Harrison, Max; Thacker, Eric; Nicholson, Stuart (2000). The Essential Jazz Records: Modernism to Postmodernism. A&C Black. p. 614. ISBN 0720118220.

- 1 2 Jurek, Thom (November 1, 2002) Review: Big Fun. Allmusic. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ↑ Jazzitude | History of Jazz Part 8: Fusion

- ↑

- ↑ "What is smooth jazz?". Smoothjazz.de. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- 1 2 Available online at: http://www.allmusic.com/explore/style/d299

- 1 2 R. Lawn, Experiencing Jazz (McGraw-Hill, 2006), ISBN 0072451793, p. 341

- ↑ George Graham review

- ↑ Ginell, Richard S. "allmusic on Roy Ayers". Allmusic.com. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ↑ Dave Lang, Perfect Sound Forever, February 1999. Access date: November 15, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Bangs, Lester. "Free Jazz / Punk Rock". Musician Magazine, 1979. Access date: July 20, 2008.

- ↑ ""House Of Zorn", Goblin Archives, at". Sonic.net. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Progressive Ears Album Reviews". Progressiveears.com. October 19, 2007. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ↑ "... circular and highly complex polymetric patterns which preserve their danceable character of popular Funk-rhythms despite their internal complexity and asymmetries ..." (Musicologist and musician Ekkehard Jost, Sozialgeschichte des Jazz, 2003, p. 377)

- ↑ Steve Coleman

- ↑ Pianist Vijay Iyer (who was chosen as "Jazz musician of the year 2010" by the Jazz Journalists Association) said: "It's hard to overstate Steve (Coleman's) influence. He's affected more than one generation, as much as anyone since John Coltrane." ()

- ↑ "His recombinant ideas about rhythm and form and his eagerness to mentor musicians and build a new vernacular have had a profound effect on American jazz." (Ben Ratliff, )

- ↑ Vijay Iyer: "It's not just that you can connect the dots by playing seven or 11 beats. What sits behind his influence is this global perspective on music and life. He has a point of view of what he does and why he does it." ()

- ↑ Michael J. West (June 2, 2010). "Jazz Articles: Steve Coleman: Vital Information". Jazztimes.com. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- ↑ "What Is M-Base?". M-base.com. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- ↑ In 2014 drummer Billy Hart said that "Coleman has quietly influenced the whole jazz musical world," and is the "next logical step" after Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman. (Source: Kristin E. Holmes, Genius grant saxman Steve Coleman redefining jazz, October 09, 2014, web portal Philly.com, Philadelphia Media Network) Already in 2010 pianist Vijay Iyer (who was chosen as "Jazz Musician of the Year 2010" by the Jazz Journalists Association) said: "To me, Steve [Coleman] is as important as [John] Coltrane. He has contributed an equal amount to the history of the music. He deserves to be placed in the pantheon of pioneering artists." (Source: Larry Blumenfeld, A Saxophonist's Reverberant Sound, June 11, 2010, The Wall Street Journal) In September 2014, Coleman was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship (a.k.a. "Genius Grant") for "redefining the vocabulary and vernaculars of contemporary music." (Source: Kristin E. Holmes, Genius grant saxman Steve Coleman redefining jazz, October 09, 2014, web portal Philly.com, Philadelphia Media Network)

- ↑ "". books.google.com. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ↑ Ratliff, Ben (September 28, 2000). "Review of L.D. 50". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ Jon Wiederhorn, "Hellyeah: Night Riders", Revolver, March 2007, p. 60-64 (link to Revolver back issues)

- ↑ Mateus, Jorge Arévalo (2004). "Boricua Rock". In Hernandez, Deborah Pacini. Rockin' las Américas: the global politics of rock in Latin/o America. D. Fernández, Héctor l'Hoeste; Zolov, Eric. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 94–98. ISBN 0-8229-5841-4.

- ↑ Music review of Overlook CD by Fromuz (2008) [RockReviews]

- ↑ Fordham, John. Review: A Tribute to Jack Johnson. The Guardian. Retrieved on 2010-01-13.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ ESC Records http://www.esc-records.de/public/index_en.html

- ↑ Tone Center http://www.shrapnelrecords.com/content/shrapnel-label-group

- ↑ AbstractLogix http://www.abstractlogix.com/

- ↑ Heads Up International http://www.concordmusicgroup.com/labels/heads-up/

- ↑ Mack Avenue Records http://www.mackavenue.com/

- ↑ Buckyball Music http://buckyballmusic.com/

- ↑ https://roncmoss.wordpress.com/about/

- ↑ http://www.concordmusicgroup.com/labels/Stretch-Records/

- ↑ Geometric Records http://www.carlfilipiak.com/reviews.html

- ↑ Alex Merck Music GmbH https://www.discogs.com/label/130531-Alex-Merck-Music-GmbH

- ↑ Wombat Records http://www.frankgambale.com/frank_gambale_discography.html

- ↑ Heptagon Records https://www.discogs.com/label/70703-Heptagon-Records

- ↑ Richie Rich Music http://www.richardhallebeek.com/bio/

- ↑ Top Jazz-Fusion Record Labels http://stevenmuschalik.com/top_jazzfusion_record_labels.html

Further reading

- Julie Coryell & Laura Friedman, ed. Jazz Rock Fusion "The People, The Music", Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-440-54409-2 pbk.

- Jazz Rock: A History, Stuart Nicholson, Éd. Canongate

- Power, Passion and Beauty – The Story of the Legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra, Walter Kolosky, ed. Abstract Logix Books

- Jazz Hot Encyclopédie "Fusion", Guy Reynard, ed. de L'instant

- Weather Report - Une Histoire du Jazz Electrique, Christophe Delbrouck, ed. Le Mot et le Reste, ISBN 978-2-915378-49-8

- The Extraordinary and Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius (10th Anniversary Edition) backbeatbooks. by Bill Milkowski

- Jeff's book : A chronology of Jeff Beck's career 1965–1980: From the Yardbirds to Jazz-Rock. Rock 'n' Roll Research Press, (2000). ISBN 978-0-9641005-3-4

- Birds of Fire: Jazz, Rock, Funk, and the Creation of Fusion (Refiguring American Music). Fellezs, Kevin; Ronald Radano, Josh Kun, (2011). Duke University Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8223-5047-7

External links

| Library resources about Jazz fusion |

- Jazzfusion.tv, the Web's largest open access source for non-commercially released classic jazz fusion audio recordings, circa 1970s–1980s, curated by Rich Rivkin, featuring works by most of the artists referenced in the above article

- A History of Jazz-Rock Fusion by Al Garcia, a writer for Guitar Player Magazine's "Spotlight" column who also performs in the group Continuum

- BendingCorners, a monthly non-profit podcast site of jazz and jazz-inspired grooves including fusion, nu-jazz, and other subgenres

- Miles Beyond, website dedicated to the jazz-rock of Miles Davis

- Miles Davis at the Isle of Wight, 1970, excerpt from Call It Anything

- Jazz Concert, electric-jazz concert venues all over the world

- Don Ellis, Tanglewood, MA, playing an electric trumpet, excerpt from Indian Lady

- ProGGnosis: Progressive Rock & Fusion, database with artist, record title and individual band member search capabilities. Contains reviews and discographies, album covers and links. On-line since Feb 2000.

- JazzRock-Radio.com, artist promotional radio show streaming jazz fusion, jazz rock from the 1970s to new releases from all over the globe