Berlin

| Berlin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State of Germany | ||||||||

From top: Skyline including the TV Tower, Brandenburg Gate, Berlin International Film Festival, East Side Gallery (Berlin Wall), Alte Nationalgalerie, Reichstag building (Bundestag) | ||||||||

| ||||||||

Location within European Union and Germany | ||||||||

| Coordinates: 52°31′N 13°23′E / 52.517°N 13.383°ECoordinates: 52°31′N 13°23′E / 52.517°N 13.383°E | ||||||||

| Country | Germany | |||||||

| Government | ||||||||

| • Governing Mayor | Michael Müller (politician) (SPD) | |||||||

| • Governing parties | SPD / CDU | |||||||

| • Bundesrat votes | 4 (of 69) | |||||||

| Area | ||||||||

| • City | 891.7 km2 (344.3 sq mi) | |||||||

| Elevation | 34 m (112 ft) | |||||||

| Population (2015)[1] | ||||||||

| • City | 3,610,156 | |||||||

| • Density | 4,000/km2 (10,000/sq mi) | |||||||

| • Metro | 6,004,857 | |||||||

| Demonym(s) | Berliner (m), Berlinerin (f) | |||||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |||||||

| Postal code(s) | 10115–14199 | |||||||

| Area code(s) | 030 | |||||||

| ISO 3166 code | DE-BE | |||||||

| Vehicle registration | B[2] | |||||||

| GDP/ Nominal | €124/ $137 billion (2015) [3] | |||||||

| GDP per capita | €35,600/ $40,000 (2015) | |||||||

| NUTS Region | DE3 | |||||||

| Website | berlin.de | |||||||

Berlin (/bərˈlɪn/, German: [bɛɐ̯ˈliːn]) is the capital and the largest city of Germany as well as one of its 16 states. With a population of approximately 3.6 million people,[4] Berlin is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Located in northeastern Germany on the banks of Rivers Spree and Havel, it is the centre of the Berlin-Brandenburg Metropolitan Region, which has about 6 million residents from more than 180 nations.[6][7][8][9] Due to its location in the European Plain, Berlin is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. Around one-third of the city's area is composed of forests, parks, gardens, rivers and lakes.[10]

First documented in the 13th century and situated at the crossing of two important historic trade routes,[11] Berlin became the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg (1417–1701), the Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918), the German Empire (1871–1918), the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and the Third Reich (1933–1945).[12] Berlin in the 1920s was the third largest municipality in the world.[13] After World War II, the city was divided; East Berlin became the capital of East Germany while West Berlin became a de facto West German exclave, surrounded by the Berlin Wall (1961–1989) and East Germany territory.[14] Following German reunification in 1990, Berlin once again became the capital of a unified Germany.

Berlin is a world city of culture, politics, media and science.[15][16][17][18] Its economy is based on high-tech firms and the service sector, encompassing a diverse range of creative industries, research facilities, media corporations and convention venues.[19][20] Berlin serves as a continental hub for air and rail traffic and has a highly complex public transportation network. The metropolis is a popular tourist destination.[21] Significant industries also include IT, pharmaceuticals, biomedical engineering, clean tech, biotechnology, construction and electronics.

Modern Berlin is home to world renowned universities, orchestras, museums, entertainment venues and is host to many sporting events.[22] Its urban setting has made it a sought-after location for international film productions.[23] The city is well known for its festivals, diverse architecture, nightlife, contemporary arts and a high quality of living.[24] Over the last decade Berlin has seen the emergence of a cosmopolitan entrepreneurial scene.[25]

History

Etymology

The name Berlin has its roots in the language of West Slavic inhabitants of the area of today's Berlin, and may be related to the Old Polabian stem berl-/birl- ("swamp").[26] All German place names ending on -ow, -itz and -in, of which there are many east of the River Elbe, are of Slavic origin (Germania Slavica). There are many boroughs of Slavic origin in the city: Berlin-Karow, Berlin-Malchow, Berlin-Pankow, Berlin-Spandau (earlier: Spandow), Berlin-Gatow, Berlin-Kladow, Berlin-Steglitz, Berlin-Lankwitz, Berlin-Britz, Berlin-Buckow, Berlin-Rudow, Berlin-Alt-Treptow, Berlin-Schmöckwitz, Berlin-Marzahn and Berlin-Köpenick. Since the Ber- at the beginning sounds like the German word Bär (bear), there appears a bear in the coat of arms of the city. It is therefore a canting arm.

12th to 16th centuries

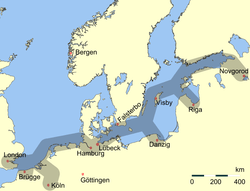

The earliest evidence of settlements in the area of today's Berlin are a wooden rod dated from approximately 1192[27] and leftovers of wooden houseparts dated to 1174 found in a 2012 excavation in Berlin Mitte.[28] The first written records of towns in the area of present-day Berlin date from the late 12th century. Spandau is first mentioned in 1197 and Köpenick in 1209, although these areas did not join Berlin until 1920.[29] The central part of Berlin can be traced back to two towns. Cölln on the Fischerinsel is first mentioned in a 1237 document, and Berlin, across the Spree in what is now called the Nikolaiviertel, is referenced in a document from 1244.[27] 1237 is considered the founding date of the city.[30] The two towns over time formed close economic and social ties, and profited from the staple right on the two important trade routes Via Imperii and from Bruges to Novgorod.[11] In 1307, they formed an alliance with a common external policy, their internal administrations still being separated.[31][32]

In 1415 Frederick I became the elector of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, which he ruled until 1440.[33] During the 15th century, his successors established Berlin-Cölln as capital of the margraviate, and subsequent members of the Hohenzollern family ruled in Berlin until 1918, first as electors of Brandenburg, then as kings of Prussia, and eventually as German emperors. In 1443 Frederick II Irontooth started the construction of a new royal palace in the twin city Berlin-Cölln. The protests of the town citizens against the building culminated in 1448, in the "Berlin Indignation" ("Berliner Unwille").[34][35] This protest was not successful and the citizenry lost many of its political and economic privileges. After the royal palace was finished in 1451, it gradually came into use. From 1470, with the new elector Albrecht III Achilles, Berlin-Cölln became the new royal residence.[32] Officially, the Berlin-Cölln palace became permanent residence of the Brandenburg electors of the Hohenzollerns from 1486, when John Cicero came to power.[36] Berlin-Cölln, however, had to give up its status as a free Hanseatic city. In 1539, the electors and the city officially became Lutheran.[37]

17th to 19th centuries

The Thirty Years' War between 1618 and 1648 devastated Berlin. One third of its houses were damaged or destroyed, and the city lost half of its population.[38] Frederick William, known as the "Great Elector", who had succeeded his father George William as ruler in 1640, initiated a policy of promoting immigration and religious tolerance.[39] With the Edict of Potsdam in 1685, Frederick William offered asylum to the French Huguenots.[40] By 1700, approximately 30 percent of Berlin's residents were French, because of the Huguenot immigration.[41] Many other immigrants came from Bohemia, Poland, and Salzburg.[42]

Since 1618 the Margraviate of Brandenburg had been in personal union with the Duchy of Prussia. In 1701 the dual state formed the Kingdom of Prussia, as Frederick III, Elector of Brandenburg crowned himself as king Frederick I in Prussia. Berlin became the capital of the new Kingdom. This was a successful attempt to centralise the capital in the very outspread state, and it was the first time the city began to grow. In 1709, Berlin merged with the four cities of Cölln, Friedrichswerder, Friedrichstadt and Dorotheenstadt under the name Berlin, "Haupt- und Residenzstadt Berlin".[31]

In 1740 Frederick II, known as Frederick the Great (1740–1786), came to power.[43] Under the rule of Frederick II, Berlin became a center of the Enlightenment, but also, was briefly occupied during the Seven Years' War by the Russian army.[44] Following France's victory in the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte marched into Berlin in 1806, but granted self-government to the city.[45] In 1815 the city became part of the new Province of Brandenburg.[46]

The Industrial Revolution transformed Berlin during the 19th century; the city's economy and population expanded dramatically, and it became the main railway hub and economic centre of Germany. Additional suburbs soon developed and increased the area and population of Berlin. In 1861 neighbouring suburbs including Wedding, Moabit and several others were incorporated into Berlin.[47] In 1871 Berlin became capital of the newly founded German Empire.[48] In 1881 it became a city district separate from Brandenburg.[49]

20th to 21st centuries

In the early 20th century, Berlin had become a fertile ground for the German Expressionist movement.[50] In fields such as architecture, painting and cinema new forms of artistic styles were invented. At the end of the First World War in 1918, a republic was proclaimed by Philipp Scheidemann at the Reichstag building. In 1920 the Greater Berlin Act incorporated dozens of suburban cities, villages and estates around Berlin into an expanded city. The act increased the area of Berlin from 66 to 883 km2 (25 to 341 sq mi). The population almost doubled and Berlin had a population of around four million. During the Weimar era, Berlin underwent political unrest due to economic uncertainties, but also became a renowned centre of the Roaring Twenties. The metropolis experienced its heyday as a major world capital and was known for its leadership roles in science, technology, arts, the humanities, city planning, film, higher education, government and industries. Albert Einstein rose to public prominence during his years in Berlin, being awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921.

In 1933 Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power. NSDAP rule diminished Berlin's Jewish community from 160,000 (one-third of all Jews in the country) to about 80,000 as a result of emigration between 1933 and 1939. After Kristallnacht in 1938, thousands of the city's Jews were imprisoned in the nearby Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Starting in early 1943, many were shipped to death camps, such as Auschwitz.[51] During World War II, large parts of Berlin were destroyed in the 1943–45 air raids and during the Battle of Berlin. Around 125,000 civilians were killed.[52] After the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, Berlin received large numbers of refugees from the Eastern provinces. The victorious powers divided the city into four sectors, analogous to the occupation zones into which Germany was divided. The sectors of the Western Allies (the United States, the United Kingdom and France) formed West Berlin, while the Soviet sector formed East Berlin.[53]

All four Allies shared administrative responsibilities for Berlin. However, in 1948, when the Western Allies extended the currency reform in the Western zones of Germany to the three western sectors of Berlin, the Soviet Union imposed a blockade on the access routes to and from West Berlin, which lay entirely inside Soviet-controlled territory. The Berlin airlift, conducted by the three western Allies, overcame this blockade by supplying food and other supplies to the city from June 1948 to May 1949.[54] In 1949 the Federal Republic of Germany was founded in West Germany and eventually included all of the American, British and French zones, excluding those three countries' zones in Berlin, while the Marxist-Leninist German Democratic Republic was proclaimed in East Germany. West Berlin officially remained an occupied city, but it politically was aligned with the Federal Republic of Germany despite West Berlin's geographic isolation. Airline service to West Berlin was granted only to American, British and French airlines.

The founding of the two German states increased Cold War tensions. West Berlin was surrounded by East German territory, and East Germany proclaimed the Eastern part as its capital, a move that was not recognised by the western powers. East Berlin included most of the historic centre of the city. The West German government established itself in Bonn.[55] In 1961 East Germany began the building of the Berlin Wall between East and West Berlin, and events escalated to a tank standoff at Checkpoint Charlie. West Berlin was now de facto a part of West Germany with a unique legal status, while East Berlin was de facto a part of East Germany. John F. Kennedy gave his "Ich bin ein Berliner" – speech in 1963 underlining the US support for the Western part of the city. Berlin was completely divided. Although it was possible for Westerners to pass from one to the other side through strictly controlled checkpoints, for most Easterners travel to West Berlin or West Germany was prohibited by the government of East Germany. In 1971, a Four-Power agreement guaranteed access to and from West Berlin by car or train through East Germany.[56]

In 1989, with the end of the Cold War and pressure from the East German population, the Berlin Wall fell on 9 November and was subsequently mostly demolished. Today, the East Side Gallery preserves a large portion of the wall. On 3 October 1990, the two parts of Germany were reunified as the Federal Republic of Germany and Berlin again became the official German capital. In 1991, the German Parliament, the Bundestag, voted to move the seat of the German capital from Bonn to Berlin, which was completed in 1999. On 18 June 1994 soldiers from the United States, France and Britain marched in a parade which was part of the ceremonies to mark the final withdrawal of foreign troops allowing a reunified Berlin.[57] Berlin's 2001 administrative reform merged several districts. The number of boroughs was reduced from 23 to 12. In 2006, the FIFA World Cup Final was held in Berlin.

Geography

Topography

Berlin is situated in northeastern Germany, in an area of low-lying marshy woodlands with a mainly flat topography, part of the vast Northern European Plain which stretches all the way from northern France to western Russia. The Berliner Urstromtal (an ice age glacial valley), between the low Barnim Plateau to the north and the Teltow Plateau to the south, was formed by meltwater flowing from ice sheets at the end of the last Weichselian glaciation. The Spree follows this valley now. In Spandau, a borough in the west of Berlin, the Spree empties into the river Havel, which flows from north to south through western Berlin. The course of the Havel is more like a chain of lakes, the largest being the Tegeler See and the Großer Wannsee. A series of lakes also feeds into the upper Spree, which flows through the Großer Müggelsee in eastern Berlin.[58]

Substantial parts of present-day Berlin extend onto the low plateaus on both sides of the Spree Valley. Large parts of the boroughs Reinickendorf and Pankow lie on the Barnim Plateau, while most of the boroughs of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Tempelhof-Schöneberg, and Neukölln lie on the Teltow Plateau.

The borough of Spandau lies partly within the Berlin Glacial Valley and partly on the Nauen Plain, which stretches to the west of Berlin. Since 2015, the highest elevation in Berlin is found on the Arkenberge hills in Pankow, at 122 m (400 ft). Through the dumping of construction debris, they surpassed Teufelsberg (120.1 m), a hill made of rubble from the ruins of the Second World War.[59] The highest natural elevation is found on the Müggelberge at 114.7 m, and the lowest at the Spektesee in Spandau, at 28.1 m (92 ft).[60]

Climate

Berlin has a Maritime temperate climate (Cfb) according to the Köppen climate classification system.[61] There are significant influences of mild continental climate due to its inland position, with frosts being common in winter and there being larger temperature differences between seasons than typical for many oceanic climates. Furthermore, Berlin is classified as a temperate continental climate (Dc) under the Trewartha climate scheme.[62]

Summers are warm and sometimes humid with average high temperatures of 22–25 °C (72–77 °F) and lows of 12–14 °C (54–57 °F). Winters are cool with average high temperatures of 3 °C (37 °F) and lows of −2 to 0 °C (28 to 32 °F). Spring and autumn are generally chilly to mild. Berlin's built-up area creates a microclimate, with heat stored by the city's buildings and pavement. Temperatures can be 4 °C (7 °F) higher in the city than in the surrounding areas.[63]

Annual precipitation is 570 millimeters (22 in) with moderate rainfall throughout the year. Snowfall mainly occurs from December through March.[64]

| Climate data for Berlin- Tempelhof (1971–2000), extremes (1876– 2015) (Source: DWD) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

31.3 (88.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

35.9 (96.6) |

38.1 (100.6) |

38.0 (100.4) |

34.2 (93.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

38.1 (100.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

18.9 (66) |

21.6 (70.9) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

7.1 (44.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

13.36 (56.05) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

1.4 (34.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.9 (48) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.9 (66) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

4.7 (40.5) |

2.0 (35.6) |

9.67 (49.42) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

2.2 (36) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

5.88 (42.59) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.1 (−9.6) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−16.5 (2.3) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−16.0 (3.2) |

−20.5 (−4.9) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 42.3 (1.665) |

33.3 (1.311) |

40.5 (1.594) |

37.1 (1.461) |

53.8 (2.118) |

68.7 (2.705) |

55.5 (2.185) |

58.2 (2.291) |

45.1 (1.776) |

37.3 (1.469) |

43.6 (1.717) |

55.3 (2.177) |

570.7 (22.469) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.0 | 8.0 | 9.1 | 7.8 | 8.9 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 9.6 | 11.4 | 101.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 46.5 | 73.5 | 120.9 | 159.0 | 220.1 | 222.0 | 217.0 | 210.8 | 156.0 | 111.6 | 51.0 | 37.2 | 1,625.6 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[65] HKO[66][67] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Berlin's history has left the city with a highly eclectic array of architecture and buildings. The city's appearance today is predominantly shaped by the key role it played in Germany's history in the 20th century. Each of the national governments based in Berlin – the Kingdom of Prussia, the 1871 German Empire, the Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany, East Germany, and now the reunified Germany – initiated ambitious reconstruction programs, with each adding its own distinctive style to the city's architecture.

Berlin was devastated by bombing raids, fires and street battles during World War II, and many of the buildings that had remained after the war were demolished in the post-war period in both West and East Berlin. Much of this demolition was initiated by municipal architecture programs to build new residential or business quarters and main roads. Many ornaments of pre-war buildings were destroyed following modernist dogmas. While in both systems and in reunified Berlin, various important heritage monuments were also (partly) reconstructed, including the Forum Fridericianum with e.g., the State Opera (1955), Charlottenburg Palace (1957), the main monuments of the Gendarmenmarkt (1980s), Kommandantur (2003) and the project to reconstruct the baroque façades of the City Palace. A number of new buildings is inspired by historical predecessors or the general classical style of Berlin, such as Hotel Adlon.

Clusters of high-rise buildings emerge at e.g., Potsdamer Platz, City West and Alexanderplatz. Berlin has three of the top 40 tallest buildings in Germany.

Architecture

The Fernsehturm (TV tower) at Alexanderplatz in Mitte is among the tallest structures in the European Union at 368 m (1,207 ft). Built in 1969, it is visible throughout most of the central districts of Berlin. The city can be viewed from its 204 m (669 ft) high observation floor. Starting here the Karl-Marx-Allee heads east, an avenue lined by monumental residential buildings, designed in the Socialist Classicism style. Adjacent to this area is the Rotes Rathaus (City Hall), with its distinctive red-brick architecture. In front of it is the Neptunbrunnen, a fountain featuring a mythological group of Tritons, personifications of the four main Prussian rivers and Neptune on top of it.

The Brandenburg Gate is an iconic landmark of Berlin and Germany; it stands as a symbol of eventful European history and of unity and peace. The Reichstag building is the traditional seat of the German Parliament. It was remodelled by British architect Norman Foster in the 1990s and features a glass dome over the session area, which allows free public access to the parliamentary proceedings and magnificent views of the city.

The East Side Gallery is an open-air exhibition of art painted directly on the last existing portions of the Berlin Wall. It is the largest remaining evidence of the city's historical division.

The Gendarmenmarkt is a neoclassical square in Berlin, the name of which derives from the headquarters of the famous Gens d'armes regiment located here in the 18th century. It is bordered by two similarly designed cathedrals, the Französischer Dom with its observation platform and the Deutscher Dom. The Konzerthaus (Concert Hall), home of the Berlin Symphony Orchestra, stands between the two cathedrals.

The Museum Island in the River Spree houses five museums built from 1830 to 1930 and is a UNESCO World Heritage site. Restoration and the construction of a main entrance to all museums, as well as the reconstruction of the Stadtschloss is continuing.[68][69] Also located on the island and adjacent to the Lustgarten and palace is Berlin Cathedral, emperor William II's ambitious attempt to create a Protestant counterpart to St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. A large crypt houses the remains of some of the earlier Prussian royal family. St. Hedwig's Cathedral is Berlin's Roman Catholic cathedral.

.jpg)

Unter den Linden is a tree-lined east–west avenue from the Brandenburg Gate to the site of the former Berliner Stadtschloss, and was once Berlin's premier promenade. Many Classical buildings line the street and part of Humboldt University is located there. Friedrichstraße was Berlin's legendary street during the Golden Twenties. It combines 20th-century traditions with the modern architecture of today's Berlin.

Potsdamer Platz is an entire quarter built from scratch after 1995 after the Wall came down.[70] To the west of Potsdamer Platz is the Kulturforum, which houses the Gemäldegalerie, and is flanked by the Neue Nationalgalerie and the Berliner Philharmonie. The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, a Holocaust memorial, is situated to the north.[71]

The area around Hackescher Markt is home to fashionable culture, with countless clothing outlets, clubs, bars, and galleries. This includes the Hackesche Höfe, a conglomeration of buildings around several courtyards, reconstructed around 1996. The nearby New Synagogue is the center of Jewish culture.

_(6340508573).jpg)

The Straße des 17. Juni, connecting the Brandenburg Gate and Ernst-Reuter-Platz, serves as the central east-west axis. Its name commemorates the uprisings in East Berlin of 17 June 1953. Approximately halfway from the Brandenburg Gate is the Großer Stern, a circular traffic island on which the Siegessäule (Victory Column) is situated. This monument, built to commemorate Prussia's victories, was relocated in 1938–39 from its previous position in front of the Reichstag.

The Kurfürstendamm is home to some of Berlin's luxurious stores with the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church at its eastern end on Breitscheidplatz. The church was destroyed in the Second World War and left in ruins. Nearby on Tauentzienstraße is KaDeWe, claimed to be continental Europe's largest department store. The Rathaus Schöneberg, where John F. Kennedy made his famous "Ich bin ein Berliner!" speech, is situated in Tempelhof-Schöneberg.

West of the center, Schloss Bellevue is the residence of the German President. Schloss Charlottenburg, which was burnt out in the Second World War is the largest historical palace in Berlin.

The Funkturm Berlin is a 150 m (490 ft) tall lattice radio tower in the fairground area, built between 1924 and 1926. It is the only observation tower which stands on insulators and has a restaurant 55 m (180 ft) and an observation deck 126 m (413 ft) above ground, which is reachable by a windowed elevator.

The Oberbaumbrücke is Berlin's most iconic bridge, crossing the River Spree. It was a former East-West border crossing and connects the boroughs of Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg. It was completed in a brick gothic style in 1896. The center portion has been reconstructed with a steel frame after having been destroyed in 1945. The bridge has an upper deck for the Berlin U-Bahn line U1.

Demographics

On 31 December 2015 the city-state of Berlin had a population of 3,610,156 registered inhabitants[4] in an area of 891.85 km2 (344.35 sq mi).[72] The city's population density was 4,048 inhabitants per km2. Berlin is the second most populous city proper in the EU. The urban area of Berlin comprised about 4.1 million people in 2014 in an area of 1,347 km2 (520 sq mi), making it the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union.[5][73] The urban agglomeration of the metropolis was home to about 4.5 million in an area of 5,370 km2 (2,070 sq mi). As of 2014 the functional urban area was home to about 5 million people in an area of approximately 15,000 km2 (5,792 sq mi).[74] The entire Berlin-Brandenburg capital region has a population of more than 6 million in an area of 30,370 km2 (11,726 sq mi).[75]

In 2014, the city state Berlin had 37.368 live births (+6,6%), a record number since 1991. The number of deaths was 32.314. Almost 2.0 million households were counted in the city. 54 percent of them were single-person households. More than 337.000 families with children under the age of 18 lived in Berlin. In 2014 the German capital registered a migration surplus of approximately 40.000 people.[76]

National and international migration into the city has a long history. In 1685, following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in France, the city responded with the Edict of Potsdam, which guaranteed religious freedom and tax-free status to French Huguenot refugees for ten years. The Greater Berlin Act in 1920 incorporated many suburbs and surrounding cities of Berlin. It formed most of the territory that comprises modern Berlin and increased the population from 1.9 million to 4 million.

Active immigration and asylum politics in West Berlin triggered waves of immigration in the 1960s and 1970s. Currently, Berlin is home to about 200,000 Turks,[77] making it the largest Turkish community outside of Turkey. In the 1990s the Aussiedlergesetze enabled immigration to Germany of some residents from the former Soviet Union. Today ethnic Germans from countries of the former Soviet Union make up the largest portion of the Russian-speaking community.[78] The last decade experienced an influx from various Western countries and some African regions.[79] Young Germans, EU-Europeans and Israelis have settled in the city.[80]

International communities

| Registered residents (2014)[81][82] | |

| Citizenship | Population |

|---|---|

| | 2,988,824 |

| | 98,659 |

| | 53,304 |

| | 25,250 |

| | 21,393 |

| | 20,052 |

| | 19,872 |

| | 17,644 |

| | 15,710 |

| | 14,825 |

| | 13,767 |

| | 13,695 |

| | 13,456 |

| | 12,491 |

| Other European | 107,126 |

| Other Asian | 69,999 |

| African Countries | 23,918 |

| Other Americas | 16,158 |

| Other | 16,005 |

In December 2015, there were 621,075 registered residents of foreign nationality, and another 457,016 German citizens with a "migration background",[4] meaning they or one of their parents immigrated after 1955.[82] Foreign residents of Berlin originate from approximately 190 different countries.[83] In 2008, about 25–30% of the population had foreign born parents.[84] 45 percent of the residents under the age of 18 have foreign roots.[85] Berlin in 2009 was estimated to have from 100,000 to 250,000 non-registered inhabitants.[86]

There are more than 20 non-indigenous communities with a population of at least 10,000 people, including Turkish, Polish, Russian, Lebanese, Palestinian, Serbian, Italian, Bosnian, Vietnamese, American, Romanian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Chinese, Austrian, Ukrainian, French, British, Spanish, Israeli, Thai, Iranian, Egyptian and Syrian communities.

Languages

German is the official and predominant spoken language in Berlin. It is a West Germanic language that derives most of its vocabulary from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family. German is one of 24 languages of the European Union,[87] and one of the three working languages of the European Commission.

Berlinerisch or Berlinisch is a dialect of Berlin Brandenburgish German spoken in Berlin and the surrounding metropolitan area. It originates from a Mark Brandenburgish variant. The dialect is now seen more as a sociolect, largely through increased immigration and trends among the educated population to speak standard German in everyday life.

The most-commonly-spoken foreign languages in Berlin are Turkish, English, Russian, Arabic, Polish, Kurdish, Vietnamese, Serbian, Croatian and French. Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, Serbo-Croatian are heard more often in the western part, due to the large Middle Eastern and former-Yugoslavian communities. English, Vietnamese, Russian, and Polish have more native speakers in eastern Berlin.[88]

Religion

More than 60% of Berlin residents have no registered religious affiliation.[89] The largest denomination in 2010 was the Protestant regional church body – the Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg-Silesian Upper Lusatia (EKBO) – a United church. EKBO is a member of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) and Union Evangelischer Kirchen (UEK), and accounts for 18.7% of the local population.[90] The Roman Catholic Church has 9.1% of residents registered as its members.[90] About 2.7% of the population identify with other Christian denominations (mostly Eastern Orthodox, but also various Protestants).[91] An estimated 200,000–350,000 Muslims reside in Berlin, making up about 6–10 percent of the population. 0.9% of Berliners belong to other religions.[92] Of the estimated population of 30,000–45,000 Jewish residents,[93] approximately 12,000 are registered members of religious organizations.[91]

Berlin is the seat of the Roman Catholic archbishop of Berlin and EKBO's elected chairperson is titled the bishop of EKBO. Furthermore, Berlin is the seat of many Orthodox cathedrals, such as the Cathedral of St. Boris the Baptist, one of the two seats of the Bulgarian Orthodox Diocese of Western and Central Europe, and the Resurrection of Christ Cathedral of the Diocese of Berlin (Patriarchate of Moscow).

The faithful of the different religions and denominations maintain many places of worship in Berlin. The Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church has eight parishes of different sizes in Berlin.[94] There are 36 Baptist congregations (within Union of Evangelical Free Church Congregations in Germany), 29 New Apostolic Churches, 15 United Methodist churches, eight Free Evangelical Congregations, four Churches of Christ, Scientist (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 11th), six congregations of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, an Old Catholic church, and an Anglican church in Berlin.

Berlin has more than 80 mosques,[95] 11 synagogues, and two Buddhist temples, in addition to a number of humanist and atheist groups.

Government

City state

Since the reunification on 3 October 1990, Berlin has been one of the three city states in Germany among the present 16 states of Germany. The city and state parliament is the House of Representatives (Abgeordnetenhaus), which currently has 141 seats. Berlin's executive body is the Senate of Berlin (Senat von Berlin). The Senate of Berlin consists of the Governing Mayor (Regierender Bürgermeister) and up to eight senators holding ministerial positions, one of them holding the official title "Mayor" (Bürgermeister) as deputy to the Governing Mayor. The total annual state budget of Berlin in 2015 exceeded €24.5 ($30.0) billion including a budget surplus of €205 ($240) million.[96]

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) and The Left (Die Linke) took control of the city government after the 2001 state election and won another term in the 2006 state election.[97] Since the 2011 state election, there has been a coalition of the Social Democratic Party with the Christian Democratic Union.

The Governing Mayor is simultaneously Lord Mayor of the city (Oberbürgermeister der Stadt) and Prime Minister of the Federal State (Ministerpräsident des Bundeslandes). The office of Berlin's Governing Mayor is in the Rotes Rathaus (Red City Hall). Since 2014 this office has been held by Michael Müller of the SPD.[98]

Boroughs

Berlin is subdivided into twelve boroughs or districts (Bezirke). Each borough contains a number of subdistricts or neighborhoods (Ortsteile), which often have historic roots in older municipalities that predate the formation of Greater Berlin on 1 October 1920 and became urbanized and incorporated into the city. Many residents strongly identify with their subdistricts or districts. At present, Berlin consists of 96 subdistricts, which are commonly made up of several smaller residential areas or quarters, called Kiez in the Berlin dialect.

Each borough is governed by a borough council (Bezirksamt) consisting of five councilors (Bezirksstadträte) including the borough mayor (Bezirksbürgermeister). The borough council is elected by the borough assembly (Bezirksverordnetenversammlung). The boroughs of Berlin are not independent municipalities. The power of borough administration is limited and subordinate to the Senate of Berlin. The borough mayors form the council of mayors (Rat der Bürgermeister), led by the city's governing mayor, which advises the senate. The neighborhoods have no local government bodies.

Twin towns – sister cities

Berlin maintains official partnerships with 17 cities.[99] Town twinning between Berlin and other cities began with sister city Los Angeles in 1967. East Berlin's partnerships were canceled at the time of German reunification and later partially reestablished. West Berlin's partnerships had previously been restricted to the borough level. During the Cold War era, the partnerships had reflected the different power blocs, with West Berlin partnering with capitals in the West, and East Berlin mostly partnering with cities from the Warsaw Pact and its allies.

There are several joint projects with many other cities, such as Beirut, Belgrade, São Paulo, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Johannesburg, Mumbai, Oslo, Shanghai, Seoul, Sofia, Sydney, New York City and Vienna. Berlin participates in international city associations such as the Union of the Capitals of the European Union, Eurocities, Network of European Cities of Culture, Metropolis, Summit Conference of the World's Major Cities, and Conference of the World's Capital Cities. Berlin's official sister cities are:[99]

- 1967

Los Angeles, United States

Los Angeles, United States - 1987

Paris, France

Paris, France - 1988

Madrid, Spain

Madrid, Spain - 1989

Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul, Turkey - 1991

Warsaw, Poland[100]

Warsaw, Poland[100] - 1991

Moscow, Russia

Moscow, Russia - 1992

.svg.png) Brussels, Belgium

Brussels, Belgium - 1992

Budapest, Hungary[101]

Budapest, Hungary[101] - 1993

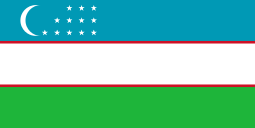

Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Tashkent, Uzbekistan - 1993

Mexico City, Mexico

Mexico City, Mexico - 1993

Jakarta, Indonesia

Jakarta, Indonesia - 1994

Beijing, China

Beijing, China - 1994

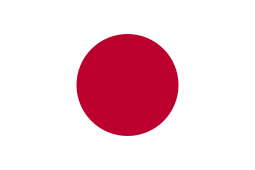

Tokyo, Japan

Tokyo, Japan - 1994

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires, Argentina - 1995

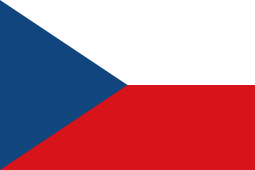

Prague, Czech Republic[102]

Prague, Czech Republic[102] - 2000

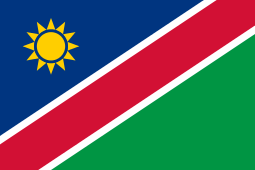

Windhoek, Namibia

Windhoek, Namibia - 2000

London, United Kingdom

London, United Kingdom

Capital city

Berlin is the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany. The President of Germany, whose functions are mainly ceremonial under the German constitution, has his official residence in Schloss Bellevue.[103] Berlin is the seat of the German executive, housed in the Chancellery, the Bundeskanzleramt. Facing the Chancellery is the Bundestag, the German Parliament, housed in the renovated Reichstag building since the government moved back to Berlin in 1998. The Bundesrat ("federal council", performing the function of an upper house) is the representation of the Federal States (Bundesländer) of Germany and has its seat at the former Prussian House of Lords. The total annual federal budget managed by the German government exceeded €310 ($375) billion in 2013.[104]

-

The Italian embassy

-

The Federal Ministry of Finance

The relocation of the federal government and Bundestag to Berlin was completed in 1999, however with some ministries as well as some minor departments retained in the federal city Bonn, the former capital of West Germany. Discussions to move the remaining branches continue.[105] The ministries and departments of Defence, Justice and Consumer Protection, Finance, Interior, Foreign, Economic Affairs and Energy, Labour and Social Affairs , Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety, Food and Agriculture, Economic Cooperation and Development, Health, Transport and Digital Infrastructure and Education and Research are based in the capital.

Berlin hosts 158 foreign embassies[106] as well as the headquarters of many think tanks, trade unions, non-profit organizations, lobbying groups, and professional associations. Due to the influence and international partnerships of the Federal Republic of Germany as a state, the capital city has become a venue for German and European affairs. Frequent official visits, and diplomatic consultations among governmental representatives and national leaders are common in contemporary Berlin.

Economy

In 2015 the nominal GDP of the citystate Berlin totaled €124.16 (~$142) billion compared to €117.75 in 2014,[108] an increase of about 5.4%. Berlin's economy is dominated by the service sector, with around 84% of all companies doing business in services. In 2015, the total labour force in Berlin was 1.85 million. The unemployment rate reached a 24-year low in November 2015 and stood at 10.0% .[109] From 2012–2015 Berlin, as a German state, had the highest annual employment growth rate. Around 130,000 jobs were added in this period.[110]

Important economic sectors in Berlin include life sciences, transportation, information and communication technologies, media and music, advertising and design, biotechnology, environmental services, construction, e-commerce, retail, hotel business, and medical engineering.[111]

Research and development have economic significance for the city. The metropolitan region ranks among the top-3 innovative locations in the EU.[112] The Science and Business Park in Adlershof is the largest technology park in Germany measured by revenue.[113] Within the Eurozone, Berlin has become a center for business relocation and international investments.[114]

Companies

Many German and international companies have business or service centers in the city. For several years Berlin has been recognized as a major center of business founders.[115] In 2015 Berlin generated the most venture capital for young startup companies in Europe.[116]

Among the 10 largest employers in Berlin are the City-State of Berlin, Deutsche Bahn, the hospital provider Charité and Vivantes, the local public transport provider BVG, and Deutsche Telekom.

Daimler manufactures cars, and BMW builds motorcycles in Berlin. Bayer Health Care and Berlin Chemie are major pharmaceutical companies headquartered in the city. The second largest German airline Air Berlin is based there as well.[117]

Siemens, a Global 500 and DAX-listed company is partly headquartered in Berlin. The national railway operator Deutsche Bahn and the MDAX-listed firms Axel Springer SE and Zalando have their headquarters in the central districts.[118] Berlin has a cluster of rail technology companies and is the German headquarter or site to Bombardier Transportation,[119] Siemens Mobility,[120] Stadler Rail and Thales Transportation.[121]

Tourism and conventions

Berlin had 788 hotels with 134,399 beds in 2014.[122] The city recorded 28.7 million overnight hotel stays and 11.9 million hotel guests in 2014.[122] Tourism figures have more than doubled within the last ten years and Berlin has become the third most-visited city destination in Europe. The largest visitor groups are from Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain and the United States.

Berlin is among the top three congress cities in the world.[19] The Messe Berlin is the main convention organizing company in the city. Its main exhibition area covers more than 160,000 square metres (1,722,226 square feet). Several large-scale trade fairs like the consumer electronics trade fair IFA, the ILA Berlin Air Show, the Berlin Fashion Week (including the Bread and Butter tradeshow and Panorama Berlin),[123] the Green Week, the Fruit Logistica, the transport fair InnoTrans, the tourism fair ITB and the adult entertainment and erotic fair Venus are held annually in the city, attracting a significant number of business visitors.

Creative industries

The creative arts and entertainment business is an important and sizable sector of the economy of Berlin. The sector comprises music, film, advertising, architecture, art, design, fashion, performing arts, publishing, R&D, software,[124] TV, radio, and video games.

In 2014 around 30,500 creative companies were operating in the Berlin-Brandenburg metropolitan region, predominantly SMEs. Generating a revenue of 15.6 billion Euro and 6% of all private economic sales, the culture industry grew from 2009 to 2014 at an average rate of 5.5% per year.[125]

Berlin is an important centre in the European and German film industry.[126] It is home to more than 1,000 film and television production companies, 270 movie theaters, and around 300 national and international co-productions are filmed in the region every year.[112] The historic Babelsberg Studios and the production company UFA are located adjacent to Berlin in Potsdam. The city is also home of the German Film Academy (Deutsche Filmakademie), founded in 2003, and the European Film Academy, founded in 1988.

Media

Berlin is home to numerous magazine, newspaper, book and scientific/academic publishers, as well as their associated service industries. In addition around 20 news agencies, more than 90 regional daily newspapers and their websites, as well as the Berlin offices of more than 22 national publications such as Der Spiegel, and Die Zeit re-enforce the capital's position as Germany's epicenter for influential debate. Therefore, many international journalists, bloggers and writers live and work in the city.

Berlin is the central location to several international and regional television and radio stations.[127] The public broadcaster RBB has its headquarters in Berlin as well as the commercial broadcasters MTV Europe, VIVA, and N24. German international public broadcaster Deutsche Welle has its TV production unit in Berlin, and most national German broadcasters have a studio in the city including ZDF and RTL.

Berlin has Germany's largest number of daily newspapers, with numerous local broadsheets (Berliner Morgenpost, Berliner Zeitung, Der Tagesspiegel), and three major tabloids, as well as national dailies of varying sizes, each with a different political affiliation, such as Die Welt, Neues Deutschland, and Die Tageszeitung. The Exberliner, a monthly magazine, is Berlin's English-language periodical and La Gazette de Berlin a French-language newspaper.

Berlin is also the headquarter of major German-language publishing houses like Walter de Gruyter, Springer, the Ullstein Verlagsgruppe (publishing group), Suhrkamp and Cornelsen are all based in Berlin. Each of which publish books, periodicals, and multimedia products.

Infrastructure

Transport

Berlin's transport infrastructure is highly complex, providing a diverse range of urban mobility.[128] A total of 979 bridges cross 197 km (122 mi) of inner-city waterways. 5,422 km (3,369 mi) of roads run through Berlin, of which 77 km (48 mi) are motorways ("Autobahn").[129] In 2013, 1.344 million motor vehicles were registered in the city.[129] With 377 cars per 1000 residents in 2013 (570/1000 in Germany), Berlin as a Western global city has one of the lowest numbers of cars per capita.

Long-distance rail lines connect Berlin with all of the major cities of Germany and with many cities in neighboring European countries. Regional rail lines provide access to the surrounding regions of Brandenburg and to the Baltic Sea. The Berlin Hauptbahnhof is the largest grade-separated railway station in Europe.[130] Deutsche Bahn runs trains to domestic destinations like Hamburg, Munich, Cologne and others. It also runs an airport express rail service, as well as trains to several international destinations, e.g., Vienna, Prague, Zürich, Warsaw and Amsterdam.

- Public transport

The Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe and the Deutsche Bahn manage several dense urban public transport systems.[131]

| System | Stations/ Lines/ Net length | Passengers per year | Operator/ Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-Bahn | 166 / 15 / 332 km (206 mi) | 402 million | DB/ Mainly overground rapid transit rail system with suburban stops. |

| U-Bahn | 173 / 10 / 151 km (94 mi) | 507 million | BVG/ Mainly underground rail system. 24h-service on weekends. |

| Tram | 398 / 22 / 192 km (119 mi) | 189 million | BVG/ Operates predominantly in eastern boroughs. |

| Bus | 2627 / 149 / 1,626 km (1,010 mi) | 409 million | BVG/ Extensive services in all boroughs. 46 Night Lines |

| Ferry | 6 lines | BVG/ All modes of transport can be accessed with the same ticket.[72] |

- Airports

Berlin has two commercial international airports. Tegel Airport (TXL) is situated within the city limits. Schönefeld Airport (SXF) is located just outside Berlin's south-eastern border in the state of Brandenburg. Both airports together handled 29.5 million passengers in 2015. In 2014, 67 airlines served 163 destinations in 50 countries from Berlin.[132] Tegel Airport is an important transfer hub for Air Berlin as well as a focus city for Lufthansa and Eurowings. Schönefeld serves as an important destination for airlines like Germania, easyJet and Ryanair.

The new Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER), currently under construction, will replace Tegel as single commercial airport of Berlin.[133] The new airport will integrate old Schönefeld (SXF) facilities and is scheduled to open not before autumn 2017. Because of the rapid passenger growth at Berlin airports the passenger capacities at the BER are already considered too small for the projected demand.

- Cycling

Berlin is well known for its highly developed bicycle lane system.[134] It is estimated that Berlin has 710 bicycles per 1000 residents. Around 500,000 daily bike riders accounted for 13% of total traffic in 2009.[135] Cyclists have access to 620 km (385 mi) of bicycle paths including approximately 150 km (93 mi) of mandatory bicycle paths, 190 km (118 mi) of off-road bicycle routes, 60 km (37 mi) of bicycle lanes on roads, 70 km (43 mi) of shared bus lanes which are also open to cyclists, 100 km (62 mi) of combined pedestrian/bike paths and 50 km (31 mi) of marked bicycle lanes on roadside pavements (or sidewalks).[136]

Energy

Berlin's energy is mainly supplied by the Swedish firm Vattenfall, which relies more heavily than other electricity producers on lignite as an energy source. Because burning lignite produces harmful emissions, Vattenfall has announced its commitment to transitioning to cleaner sources, such as renewable energy.[137] In the former West Berlin, electricity was supplied chiefly by thermal power stations. To facilitate buffering during load peaks, accumulators were installed during the 1980s at some of these power stations. These were connected by static inverters to the power grid and were loaded during times of low energy consumption and unloaded during periods of high consumption.

In 1993 the power grid connections to the surrounding areas were restored. In the western districts of Berlin, nearly all power lines are underground cables; only a 380 kV and a 110 kV line, which run from Reuter substation to the urban Autobahn, use overhead lines. The Berlin 380-kV electric line was built when West Berlin's electrical grid was not connected to those of East or West Germany. This has now become the backbone of the city's energy grid.

Health

Berlin has a long history of discoveries in medicine and innovations in medical technology.[138] The modern history of medicine has been significantly influenced by scientists from Berlin. Rudolf Virchow was the founder of cellular pathology, while Robert Koch developed vaccines for anthrax, cholera, and tuberculosis.[139]

The Charité hospital complex is the largest university hospital in Europe, tracing back its origins to the year 1710. The Charité is spread over four sites and comprises 3,300 beds, around 14,000 staff, 7,000 students, and more than 60 operating theaters, and it has a turnover of over one billion euros annually.[140] The Charité is a joint institution of the Freie Universität Berlin and the Humboldt University of Berlin, including a wide range of institutes and specialized medical centers.

Among them are the German Heart Center, one of the most renowned transplantation centers, the Max-Delbrück-Center for Molecular Medicine and the Max-Planck-Institute for Molecular Genetics. The scientific research at these institutions is complemented by many research departments of companies such as Siemens and Bayer. The World Health Summit and several international health related conventions are held annually in Berlin.

Telecommunication

The digital television standard in Berlin and Germany is DVB-T. This system transmits compressed digital audio, digital video and other data in an MPEG transport stream, using coded orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing modulation. The transmission standard is scheduled to be replaced by DVB-T2 in 2018.

Berlin has commissioned the company ABL Social Federation to install several hundred free public Wireless LAN sites across the capital by 2016. The wireless networks will be concentrated mostly in central districts; 650 hotspots (325 indoor and 325 outdoor access points) will be installed.[141]

The UMTS (3G) and LTE (4G) networks of the three major cellular operators Vodafone, T-Mobile and O2 enable the use of mobile broadband applications citywide.

The Fraunhofer Heinrich Hertz Institute develops mobile and stationary broadband communication networks and multimedia systems. Focal points of independent and contract research conducted by Fraunhofer HHI are photonic components and systems, fiber optic sensor systems, and image signal processing and transmission. Future applications for broadband networks are developed as well.

Education

Berlin has 878 schools that teach 340,658 children in 13,727 classes and 56,787 trainees in businesses and elsewhere.[112] The city has a 6-year primary education program. After completing primary school, students continue to the Sekundarschule (a comprehensive school) or Gymnasium (college preparatory school). Berlin has a special bilingual school program embedded in the "Europaschule" in which children are taught the curriculum in German and a foreign language, starting in primary school and continuing in high school. Nine major European languages can be chosen as foreign languages in 29 schools.[142]

The Französisches Gymnasium Berlin, which was founded in 1689 to teach the children of Huguenot refugees, offers (German/French) instruction.[143] The John F. Kennedy School, a bilingual German–American public school located in Zehlendorf, is particularly popular with children of diplomats and the English-speaking expatriate community. Four schools teach Latin and Classical Greek. Two of them are state schools (Steglitzer Gymnasium in Steglitz and Goethe-Gymnasium in Wilmersdorf), one is Protestant (Evangelisches Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster in Wilmersdorf), and one is Jesuit (Canisius-Kolleg in the "Embassy Quarter" in Tiergarten).

Higher education

The Berlin-Brandenburg capital region is one of the most prolific centres of higher education and research in Germany and Europe. Historically, 40 Nobel Prize winners are affiliated with the Berlin-based universities.

The city has four public research universities and more than 30 private, professional, and technical colleges (Hochschulen), offering a wide range of disciplines.[144] A record number of 175,651 students were enrolled in the winter term of 2015/16.[145] Among them around 18% have an international background.

The three largest universities combined have approximately 100,000 enrolled students. There are the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin (HU Berlin) with 33,000 students, the Freie Universität Berlin (Free University of Berlin, FU Berlin) with about 33,000 students, and the Technische Universität Berlin (TU Berlin) with 33,000 students. The FU and the HU are part of the German Universities Excellence Initiative. The Universität der Künste (UdK) has about 4,000 students. The Berlin School of Economics and Law has an enrollment of about 10,000 students and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft (University of Applied Sciences for Engineering and Economics) of about 13.000 students.

Research

The city has a high density of internationally renowned research institutions, such as the Fraunhofer Society, the Leibniz Association, the Helmholtz Association, and the Max Planck Society, which are independent of, or only loosely connected to its universities.[146] In 2012, around 65,000 professional scientists were working in research and development in the city.[112]

Berlin is one of the knowledge and innovation communities (KIC) of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT).[147] The KIC is based at the Centre for Entrepreneurship at TU Berlin and has a focus in the development of IT industries. It partners with major multinational companies such as Siemens, Deutsche Telekom, and SAP.[148]

One of Europe's successful research, business and technology clusters is based at WISTA in Berlin-Adlershof, with more than 1,000 affiliated firms, university departments and scientific institutions.[149]

In addition to the libraries that are affiliated with the various universities, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin is a major research library. Its two main locations are on Potsdamer Straße and on Unter den Linden. There are also 86 public libraries in the city.[112] ResearchGate, a global social networking site for scientists, is based in Berlin.

Culture

.jpg)

Berlin is known for its numerous cultural institutions, many of which enjoy international reputation.[22][150] The diversity and vivacity of the metropolis led to a trendsetting atmosphere.[151] An innovative music, dance and art scene has developed in the 21st century.

Young people, international artists and entrepreneurs continued to settle in the city and made Berlin a popular entertainment center in the world.[152]

The expanding cultural performance of the city was underscored by the relocation of the Universal Music Group who decided to move their headquarters to the banks of the River Spree.[153] In 2005, Berlin was named "City of Design" by UNESCO.[20]

Galleries and museums

As of 2011 Berlin is home to 138 museums and more than 400 art galleries.[112] [154] The ensemble on the Museum Island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is situated in the northern part of the Spree Island between the Spree and the Kupfergraben.[22] As early as 1841 it was designated a "district dedicated to art and antiquities" by a royal decree. Subsequently, the Altes Museum was built in the Lustgarten. The Neues Museum, which displays the bust of Queen Nefertiti,[155] Alte Nationalgalerie, Pergamon Museum, and Bode Museum were built there.

Apart from the Museum Island, there are many additional museums in the city. The Gemäldegalerie (Painting Gallery) focuses on the paintings of the "old masters" from the 13th to the 18th centuries, while the Neue Nationalgalerie (New National Gallery, built by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe) specializes in 20th-century European painting. The Hamburger Bahnhof, located in Moabit, exhibits a major collection of modern and contemporary art. The expanded Deutsches Historisches Museum re-opened in the Zeughaus with an overview of German history spanning more than a millennium. The Bauhaus Archive is a museum of 20th century design from the famous Bauhaus school.

The Jewish Museum has a standing exhibition on two millennia of German-Jewish history.[156] The German Museum of Technology in Kreuzberg has a large collection of historical technical artifacts. The Museum für Naturkunde exhibits natural history near Berlin Hauptbahnhof. It has the largest mounted dinosaur in the world (a Giraffatitan). Well-preserved specimens of Tyrannosaurus Rex and the early bird Archaeopteryx are at display as well.[157]

In Dahlem, there are several museums of world art and culture, such as the Museum of Asian Art, the Ethnological Museum, the Museum of European Cultures, as well as the Allied Museum. The Brücke Museum features one of the largest collection of works by artist of the early 20th-century expressionist movement. In Lichtenberg, on the grounds of the former East German Ministry for State Security, is the Stasi Museum. The site of Checkpoint Charlie, one of the most renowned crossing points of the Berlin Wall, is still preserved. A private museum venture exhibits a comprehensive documentation of detailed plans and strategies devised by people who tried to flee from the East. The Beate Uhse Erotic Museum claims to be the world's largest erotic museum.[158]

The cityscape of Berlin displays large quantities of urban street art.[159] It has become a significant part of the city's cultural heritage and has its roots in the graffiti scene of Kreuzberg of the 1980s.[160] The Berlin Wall itself has become one of the largest open-air canvasses in the world.[161] The leftover stretch along the Spree river in Friedrichshain remains as the East Side Gallery. Berlin today is consistently rated as an important world city for street art culture.[162]

Nightlife and festivals

Berlin's nightlife has been celebrated as one of the most diverse and vibrant of its kind.[163] In the 1970s and '80s the SO36 in Kreuzberg focused on punk music. The SOUND and the Dschungel gained notoriety.[164] Throughout the 1990s, people in their 20s from many countries, particularly those in Western and Central Europe, made Berlin's club scene a premier nightlife venue. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, many historic buildings in Mitte, the former city centre of East Berlin, were illegally occupied and re-built by young squatters and became a fertile ground for underground and counterculture gatherings. The central boroughs are home to many nightclubs, including the clubs Watergate, Tresor, E-Werk and Berghain. The KitKatClub and several other locations are known for sexually uninhibited parties.

Clubs are not required to close at a fixed time on the weekends, and many parties last well into the morning, or all weekend. Berghain features the Panorama Bar, a bar that opens its shades at daybreak, allowing party-goers a panorama view of Berlin after dancing through the night. The Weekend Club near Alexanderplatz features a roof terrace that allows partying at almost any time of the day. Several venues have become a popular stage for the Neo-Burlesque scene.

Berlin has a long history of gay culture, and is an important birthplace of the LGBT rights movement. Same-sex bars and dance halls operated freely from the 1880s, and the first magazine, Der Eigene, started in 1896. By the 1920s, gays and lesbians had an unprecedented visibility in popular culture.[165][166] Today, in addition to a positive atmosphere in the wider club scene, the city again has a huge number of queer clubs and festivals. The most famous are Berlin Pride, the Christopher Street Day,[167] the Lesbian and Gay City Festival in Berlin-Schöneberg, the Kreuzberg Pride and Hustlaball.

The annual Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) with around 500,000 admissions is considered to be the largest publicly attended film festival in the world.[168][169] The Karneval der Kulturen (Carnival of Cultures), a multi-ethnic street parade celebrated every Pentecost weekend.[170] Berlin is also well known for the cultural festival, Berliner Festspiele, which includes the jazz festival JazzFest Berlin. Several technology and media art festivals and conferences are held in the city, including Transmediale and Chaos Communication Congress. The annual Berlin Festival focuses on indie rock, electronic music and synth pop and is part of the international Berlin Music Week.[171][172] Every year Berlin hosts one of the largest New Year's Eve celebrations (Silvester) in the world, attended by over a million people. The focal point is the Brandenburg Gate, where midnight fireworks are centred. Throughout the city, private fireworks displays take place in all neighbourhoods as well. Partygoers in Germany often toast the New Year with a glass of sparkling wine.

Performing arts

Berlin is home to 44 theaters and stages.[112] The Deutsches Theater in Mitte was built in 1849–50 and has operated almost continuously since then. The Volksbühne at Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz was built in 1913–14, though the company had been founded in 1890. The Berliner Ensemble, famous for performing the works of Bertolt Brecht, was established in 1949. The Schaubühne was founded in 1962 and moved to the building of the former Universum Cinema on Kurfürstendamm in 1981. With a seating capacity of 1,895 and a stage floor of 2,854 square metres (30,720 square feet), the Friedrichstadt-Palast in Berlin Mitte is the largest show palace in Europe.

Berlin has three major opera houses: the Deutsche Oper, the Berlin State Opera, and the Komische Oper. The Berlin State Opera on Unter den Linden opened in 1742 and is the oldest of the three. Its current musical director is Daniel Barenboim. The Komische Oper has traditionally specialized in operettas and is located at Unter den Linden as well. The Deutsche Oper opened in 1912 in Charlottenburg.

The city's main venue for musical theater performances are the Theater am Potsdamer Platz and Theater des Westens (built in 1895). Contemporary dance can be seen at the Radialsystem V. The Tempodrom is host to concerts and circus inspired entertainment. It also houses a multi-sensory spa experience. The Admiralspalast in Mitte has a vibrant program of variety and music events.

There are seven symphony orchestras in Berlin. The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world;[173] it is housed in the Berliner Philharmonie near Potsdamer Platz on a street named for the orchestra's longest-serving conductor, Herbert von Karajan.[174] The current principal conductor is Simon Rattle.[175] The Konzerthausorchester Berlin was founded in 1952 as the orchestra for East Berlin. Its current principal conductor is Ivan Fischer. The Haus der Kulturen der Welt presents various exhibitions dealing with intercultural issues and stages world music and conferences.[176] The Kookaburra and the Quatsch Comedy Club are known for satire and stand up comedy shows.

Cuisine

The cuisine and culinary offerings of Berlin vary greatly. Twelve restaurants in Berlin have been included in the Michelin guide of 2015, which ranks the city at the top for the number of restaurants having this distinction in Germany.[177] Apart from that, Berlin is well known for its offerings of vegetarian cuisine.[178]

Many local foods originated from north German culinary traditions and include rustic and hearty dishes with pork, goose, fish, peas, beans, cucumbers, or potatoes. Typical Berliner fares include Currywurst, Bulette and the Berliner doughnut, known in Berlin as Pfannkuchen.[179][180] German bakeries offering a variety of breads and pastries are widespread. One of Europe's largest delicatessen markets is found at the KaDeWe, and among the world’s largest chocolate stores is Fassbender & Rausch.[181]

Berlin is also home to a diverse gastronomy scene reflecting the immigrant history of the city. Turkish and Arab immigrants brought their culinary traditions to the city, such as the lahmacun and falafel, which have become common fast food staples. The modern fast food version of the döner kebab sandwich evolved in Berlin in the 1970s, and became a favorite in Germany.[182] Asian cuisine like Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, Indian, and sushi restaurants, as well as Spanish tapas bars, Italian, and Greek cuisine, can be found in many parts of the city.

Recreation

Zoologischer Garten Berlin, the older of two zoos in the city, was founded in 1844. It is the most visited zoo in Europe and presents the most diverse range of species in the world.[183] It was the home of the captive-born celebrity polar bear Knut.[184] The city's other zoo, Tierpark Friedrichsfelde, was founded in 1955.

Berlin's Botanischer Garten includes the Botanic Museum Berlin. With an area of 43 hectares (110 acres) and around 22,000 different plant species, it is one of the largest and most diverse collections of botanical life in the world. Other gardens in the city include the Britzer Garten, and the Gärten der Welt (Gardens of the World) in Marzahn.[185]

The Tiergarten, located in Mitte, is Berlin's largest park and was designed by Peter Joseph Lenné.[186] In Kreuzberg, the Viktoriapark provides a viewing point over the southern part of inner-city Berlin. Treptower Park, beside the Spree in Treptow, features a large Soviet War Memorial. The Volkspark in Friedrichshain, which opened in 1848, is the oldest park in the city, with monuments, a summer outdoor cinema and several sports areas.[187]

Potsdam is situated on the southwestern periphery of Berlin. The city was a residence of the Prussian kings and the German Kaiser, until 1918. The area around Potsdam in particular Sanssouci is known for a series of interconnected lakes and cultural landmarks. The Palaces and Parks of Potsdam and Berlin are the largest World Heritage Site in Germany.[188]

Berlin is also well known for its numerous cafés, street musicians, beach bars along the Spree River, flea markets, boutique shops and pop up stores, which are a source for recreation and leisure.[189]

Sports

Berlin has established a high-profile reputation as a host city of major international sporting events.[190] The city hosted the 1936 Summer Olympics and was the host city for the 2006 FIFA World Cup final.[191] The IAAF World Championships in Athletics was held in the Olympiastadion in 2009,[192] the Mercedes-Benz Arena hosted the Euroleague Final Four in 2009 and 2016. (In 2009, it was called O2 World)[193] In 2015 Berlin became the venue for the UEFA Champions League Final.

The annual Berlin Marathon – a course that holds the most top-10 world record runs – and the ISTAF are well-established athletic events in the city.[194] The FIVB World Tour, a beach volleyball Grand Slam event, is presented at an inner-city site every year, while the Mellowpark in Köpenick is one of the biggest skate and BMX parks in Europe.[195]

A Fan Fest at Brandenburg Gate, which attracts several hundred-thousand spectators, has become popular during international football competitions, like the UEFA European Championship.[196]

In 2013 around 600,000 Berliners were registered in one of the more than 2,300 sport and fitness clubs.[197] The city of Berlin operates more than 60 public indoor and outdoor swimming pools.[198] Berlin is the largest Olympic training centre in Germany. About 500 top athletes (15% of all German top athletes) are based there. Forty-seven elite athletes participated in the 2012 Summer Olympics. Berliners would achieve seven gold, twelve silver and three bronze medals.[199]

Several professional clubs representing the most important spectator team sports in Germany have their base in Berlin:

| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue | Head coach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hertha BSC[200] | Football | 1892 | Bundesliga | Olympiastadion | P. Dárdai |

| 1. FC Union Berlin[201] | Football | 1966 | 2. Bundesliga | Stadion An der Alten Försterei | J. Keller |

| ALBA Berlin[202] | Basketball | 1991 | BBL | Mercedes-Benz Arena | A. Çakı |

| Eisbären Berlin[203] | Ice hockey | 1954 | DEL | Mercedes-Benz Arena | U. Krupp |

| Füchse Berlin[204] | Handball | 1891 | HBL | Max-Schmeling-Halle | E. Richardsson |

See also

|

| ||||

Notes

- ↑ "Amt für Statistik Berlin Brandenburg". Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ↑ Prefixes for vehicle registration were introduced in 1906, but often changed due to the political changes after 1945. Vehicles were registered under the following prefixes: "I A" (1906 – April 1945; devalidated on 11 August 1945); no prefix, only digits (from July to August 1945), "БГ" (=BG; 1945–46, for cars, lorries and busses), "ГФ" (=GF; 1945–46, for cars, lorries and busses), "БM" (=BM; 1945–47, for motor bikes), "ГM" (=GM; 1945–47, for motor bikes), "KB" (i.e.: Kommandatura of Berlin; for all of Berlin 1947–48, continued for West Berlin until 1956), "GB" (i.e.: Greater Berlin, for East Berlin 1948–53), "I" (for East Berlin, 1953–90), "B" (for West Berlin from 1 July 1956, continued for all of Berlin since 1990).

- ↑ Baden-Württemberg, Statistisches Landesamt. "Bruttoinlandsprodukt – in jeweiligen Preisen – in Deutschland 1991 bis 2015 nach Bundesländern (WZ 2008)". vgrdl.de.

- 1 2 3 "Einwohner am Ort der Hauptwohnung am 31. Dezember 2015". Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg (in German). Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- 1 2 INSEE. "Population des villes et unités urbaines de plus de 1 million d'habitants de l'Union européenne" (in French). Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ "Daten und Fakten Hauptstadtregion". Berlin-Brandenburg.de. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Initiativkreis Europäische Metropolregionen in Deutschland: Berlin-Brandenburg". Deutsche-metropolregionen.org. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "PowerPoint-Präsentation" (PDF). Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "City Profiles Berlin". Urban Audit. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ↑ Schulte-Peevers, Andrea; Parkinson, Tom (2004). Gren Berlin. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781740594721. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- 1 2 Niederlagsrecht, Verein für die Geschichte Berlins. Retrieved 21 November 2015 (German).

- ↑ "Documents of German Unification, 1848–1871". Modern History Sourcebook. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "Topographies of Class: Modern Architecture and Mass Society in Weimar Berlin (Social History, Popular Culture and Politics in Germany).". www.h-net.org. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ↑ "Berlin Wall". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "Berlin – Capital of Germany". German Embassy in Washington. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ Davies, Catriona (10 April 2010). "Revealed: Cities that rule the world – and those on the rise". CNN. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ↑ Sifton, Sam (31 December 1969). "Berlin, the big canvas". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 August 2008. See also: "Sites and situations of leading cities in cultural globalisations/Media". GaWC Research Bulletin 146. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "Global Power City Index 2009" (PDF). Institute for Urban Strategies at The Mori Memorial Foundation. Tokyo, Japan. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- 1 2 "ICCA publishes top 20 country and city rankings 2007". ICCA. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- 1 2 "Berlin City of Design" (Press release). UNESCO. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "Berlin Beats Rome as Tourist Attraction as Hordes Descend". Bloomberg L.P. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 "World Heritage Site Museumsinsel". UNESCO. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "Hollywood Helps Revive Berlin's Former Movie Glory". Deutsche Welle. 9 August 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ Flint, Sunshine (12 December 2004). "The Club Scene, on the Edge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2008. See also: "Ranking of best cities in the world". City mayors. Retrieved 18 August 2008. and "The Monocle Quality Of Life Survey 2015". Monocle. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ↑ "Young Israelis are Flocking to Berlin". Newsweek. NYC, United States. 13 June 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ↑ Berger, Dieter (1999). Geographische Namen in Deutschland. Bibliographisches Institut. ISBN 3-411-06252-5.

- 1 2 "Berlin dig finds city older than thought". Associated Press.

- ↑ "Berlin ist älter als gedacht: Hausreste aus dem Jahr 1174 entdeckt". dpa. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Spandau Citadel". Berlin tourist board. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "The medieval trading center". www.berlin.de. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- 1 2 Stöver B. Geschichte Berlins. Verlag CH Beck, 2010. ISBN 978-3-406-60067-8

- 1 2 Stadtgründung Und Frühe Stadtentwicklung, Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein. Retrieved 10 June 2013

- ↑ "The Hohenzollern Dynasty". Antipas. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ Berliner Unwillen. Verein für die Geschichte Berlins e. V. Retrieved 30 May 2013

- ↑ Was den "Berliner Unwillen" erregte.. Der Tagesspiegel, 26 Oktober 2012

- ↑ "The electors' residence". www.berlin.de. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ "Berlin Cathedral". SMPProtein. Archived from the original on 18 August 2006. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "Brandenburg during the 30 Years War". WHKMLA. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ Thomas Carlyle (1853). Fraser's Magazine. J. Fraser. p. 63. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ W. Gunther Plaut (1 January 1995). Asylum: A Moral Dilemma. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-275-95196-2.

- ↑ Jeremy Gray (2007). Germany. Lonely Planet. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-74059-988-7.

- ↑ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky (23 May 2013). Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-61069-248-9.

- ↑ Gregorio F. Zaide (1965). World History. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 273. ISBN 978-971-23-1472-8.

- ↑ Marvin Perry; Myrna Chase; James Jacob; Margaret Jacob; Theodore Von Laue (1 January 2012). Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society. Cengage Learning. p. 444. ISBN 1-133-70864-1.

- ↑ Peter B. Lewis (15 February 2013). Arthur Schopenhauer. Reaktion Books. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-78023-069-6.

- ↑ Harvard Student Agencies Inc. Staff; Harvard Student Agencies, Inc. (28 December 2010). Let's Go Berlin, Prague & Budapest: The Student Travel Guide. Avalon Travel. p. 83. ISBN 1-59880-914-8.

- ↑ Andrea Schulte-Peevers (15 September 2010). Lonel Berlin. Lonely Planet. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-74220-407-9.

- ↑ Bernd Stöver (2 October 2013). Berlin: A Short History. C.H.Beck. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-406-65633-0.

- ↑ W. Paul Strassmann (15 June 2008). The Strassmanns: Science, Politics and Migration in Turbulent Times (1793–1993). Berghahn Books. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84545-416-6.

- ↑ Jack Holland; John Gawthrop (2001). The Rough Guide to Berlin. Rough Guides. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-85828-682-2.

- ↑ "Berlin".

- ↑ Clodfelter, Michael (2002), Warfare and Armed Conflicts- A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–2000 (2nd ed.), McFarland & Company, ISBN 0-7864-1204-6

- ↑ "Agreement to divide Berlin". FDR-Library. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "Berlin Airlift / Blockade". Western Allies Berlin. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ "Berlin official website; History after 1945". City of Berlin. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ↑ "Ostpolitik: The Quadripartite Agreement of September 3, 1971". US Berlin Embassy. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ Kinzer, Stephan (19 June 1994). "Allied Soldiers March to Say Farewell to Berlin". New York Times. New York City. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ "Satellite Image Berlin". Google Maps. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ Berlin hat eine neue Spitze, Qiez, 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Stefan Jacobs: Der höchste Berg von Berlin ist neuerdings in Pankow, 22 February 2015.

- ↑ "Berlin, Germany Climate Summary". Weatherbase. Retrieved 15 March 2015.