Baybayin

| Baybayin Badlit ᜊᜌ᜔ᜊᜌᜒᜈ᜔ ᜊᜇ᜔ᜎᜒᜆ᜔ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Bikol languages, Ilocano, Pangasinan, Tagalog, Visayan, other Philippine languages |

Time period | c. 13th century—18th century[1][2] |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems |

Directly related modern alphabets:

Batak Javanese Lontara Sundanese Rencong Rejang |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Tglg, 370 |

Unicode alias | Tagalog |

| U+1700–U+171F | |

Baybayin (Tagalog pronunciation: [baɪˈbaɪjɪn]; pre-kudlit: ᜊᜊᜌᜒ, post-kudlit: ᜊᜌ᜔ᜊᜌᜒᜈ᜔) (known in Unicode as Tagalog alphabet; see below), known in Visayan as badlit (ᜊᜇ᜔ᜎᜒᜆ᜔), and known in Ilocano as kur-itan/kurditan, is an ancient Philippine script derived from Brahmic scripts of India and first recorded in the 16th century.[3] It continued to be used during the Spanish colonization of the Philippines up until the late 19th century. The alphabet is well known because it was carefully documented by Catholic clergy living in the Philippines during the colonial era.

The term baybay literally means "to spell" in Tagalog. Baybayin was extensively documented by the Spanish.[4] Some have incorrectly attributed the name Alibata to it,[5][6] but that term was coined by Paul Rodríguez Verzosa[3] after the arrangement of letters of the Arabic alphabet (alif, ba, ta (alibata), "f" having been eliminated for euphony's sake).[7]

Other Brahmic scripts used currently among different ethnic groups in the Philippines are Buhid, Hanunó'o, Kulitan and Tagbanwa.

Baybayin is one of a number of individual writing systems used in Southeast Asia, nearly all of which are abugidas where any consonant is pronounced with the inherent vowel a following it—diacritics being used to express other vowels (this vowel occurs with greatest frequency in Sanskrit, and also probably in all Philippine languages). Many of these writing systems descended from ancient alphabets used in India over 2000 years ago. Although Baybayin does share some, there is no evidence that it is this old.[3]

The Archives of the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, one of the largest archives in the Philippines, currently possesses the biggest collection of extant ancient Baybayin alphabets in the world.[8][9][10]

A Baybayin bill, House Bill no.4395 and Senate Bill 1899, which is also known as the National Script Act of 2011, has been filed in the 15th Congress since 2011. It was refiled in the 17th Congress of the Philippines through Senate Bill 433 in 2016. It aims to declare Baybayin, wrongfully known as Alibata, as the national script of the Philippines. The bill mandates to put a Baybayin translation under all business and government logos. It also mandates all primary and secondary schools to teach Baybayin to their students, a move that would save the ancient script from pure extinction and revitalize the indigenous writing roots of Filipinos. The writing system being pursued by the bill is a modernized version of the Baybayin which incorporates the common segments of numerous indigenous writing forms throughout the country. The system is a more nationalistic approach due to its comprehensive range, contrary to reports saying the bill will create further regionalism or cultural disintegration.[11][12][13]

Overview

Origins

Baybayin was noted by the Spanish priest Pedro Chirino in 1604 and Antonio de Morga in 1609, to be known by most Filipinos, and was generally used for personal writings, poetry, etc. According to William Henry Scott, there were some datus from the 1590s who could not sign affidavits or oaths, and witnesses who could not sign land deeds in the 1620s.[14] There is no data on when this level of literacy was first achieved, and no history of the writing system itself. There are at least six theories about the origins of Baybayin.

Kawi

The Kawi script originated in Java, and was used across much of Maritime Southeast Asia.

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription is the earliest known written document found in the Philippines.

It is a legal document, and has inscribed on it a date of Saka era 822, corresponding to April 21, 900 AD Laguna Copperplate Inscription. It was written in the Kawi script in a variety of Old Malay containing numerous loanwords from Sanskrit and a few non-Malay vocabulary elements whose origin is ambiguous between Old Javanese and Old Tagalog. One hypothesis therefore reasons that, since Kawi is the earliest attestation of writing on the Philippines, then Baybayin may be descended from Kawi.

A second example of Kawi script can be seen on the Butuan Ivory Seal, though it has not been dated.

An earthenware burial jar, called the "Calatagan Pot," found in Batangas is inscribed with characters strikingly similar to Baybayin, and is claimed to have been inscribed ca. 1300 AD. However, its authenticity has not yet been proven.

Many of the writing systems of Southeast Asia descended from ancient scripts used in India over 2000 years ago. Although the baybayin shares some important features with these scripts, such as all the consonants being pronounced with the vowel a and the use of special marks to change this sound, there is no evidence that it is so old.

The shapes of the baybayin characters bear a slight resemblance to the ancient Kavi script of Java, Indonesia, which fell into disuse in the 15th century. However, as mentioned earlier in the Spanish accounts, the advent of the baybayin in the Philippines was considered a fairly recent event in the 16th century and the Filipinos at that time believed that their baybayin came from Borneo.

This theory is supported by the fact that the baybayin script could not show syllable final consonants, which are very common in most Philippine languages. (See Final Consonants) This indicates that the script was recently acquired and had not yet been modified to suit the needs of its new users. Also, this same shortcoming in the baybayin was a normal trait of the script and language of the Bugis people of Sulawesi, which is directly south of the Philippines and directly east of Borneo. Thus most scholars believe that the baybayin may have descended from the Buginese script or, more likely, a related lost script from the island of Sulawesi.

Although one of Ferdinand Magellan's shipmates, Antonio Pigafetta, wrote that the people of the Visayas were not literate in 1521, the baybayin had already arrived there by 1567 when Miguel López de Legazpi reported that, “They [the Visayans] have their letters and characters like those of the Malays, from whom they learned them.” B1 Then, a century later Francisco Alcina wrote about:

The characters of these natives, or, better said, those that have been in use for a few years in these parts, an art which was communicated to them from the Tagalogs, and the latter learned it from the Borneans who came from the great island of Borneo to Manila, with whom they have considerable traffic... From these Borneans the Tagalogs learned their characters, and from them the Visayans, so they call them Moro characters or letters because the Moros taught them... [the Visayans] learned [the Moros'] letters, which many use today, and the women much more than the men, which they write and read more readily than the latter.[3]

Old Sumatran "Malay" scripts

Another hypothesis states that a script or script used to write one of the Malay languages was adopted and became Baybayin. In particular, the Pallava script from Sumatra is attested to the 7th century.[15]

Old Assamese

The eastern nāgarī script was a precursor to devanāgarī. This hypothesis states that a version of this script was introduced to the Philippines via Bengal, before ultimately evolving into baybayin.

Cham

Finally, an early Cham script from Champa — in what is now southern Vietnam and southeastern Cambodia — could have been introduced or borrowed and adapted into Baybayin.

Characteristics

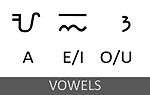

The writing system is an abugida system using consonant-vowel combinations. Each character, written in its basic form, is a consonant ending with the vowel "A". To produce consonants ending with the other vowel sounds, a mark is placed either above the consonant (to produce an "E" or "I" sound) or below the consonant (to produce an "O" or "U" sound). The mark is called a kudlit. The kudlit does not apply to stand-alone vowels. Vowels themselves have their own glyphs. There is only one symbol for D or R as they were allophones in most languages of the Philippines, where D occurred in initial, final, pre-consonantal or post-consonantal positions and R in intervocalic positions. The grammatical rule has survived in modern Filipino, so that when a d is between two vowels, it becomes an r, as in the words dangál (honour) and marangál (honourable), or dunong (knowledge) and marunong (knowledgeable), and even raw for daw (he said, she said, they said, it was said, allegedly, reportedly, supposedly) and rin for din (also, too) after vowels.[3] This variant of the script is not used for Ilokano, Pangasinan, Bikolano, and other Philippine languages to name a few, as these languages have separate symbols for D and R.

Two styles of writing

Virama Kudlit "style"

The original writing method was particularly difficult for the Spanish priests who were translating books into the vernaculars. Because of this, Francisco López introduced his own kudlit in 1620, called a sabat, that cancelled the implicit a vowel sound. The kudlit was in the form of a "+" sign,[16] in reference to Christianity. This cross-shaped kudlit functions exactly the same as the virama in the Devanagari script of India. In fact, Unicode calls this kudlit the Tagalog Sign Virama. See sample above in Characteristics Section.

"Nga" character

A single character represented "nga". The current version of the Filipino alphabet still retains "ng" as a digraph.

Punctuation

Words written in baybayin were written in a continuous flow, and the only form of punctuation was a single vertical line, or more often, a pair of vertical lines (||). These vertical lines fulfill the function of a comma, period, or unpredictably separate sets of words.[3]

Pre-colonial and colonial usage

Baybayin historically was used in Tagalog and to a lesser extent Kapampangan speaking areas. Its use spread to Ilokanos when the Spanish promoted its use with the printing of Bibles. Related scripts, such as Hanunóo, Buhid, and Tagbanwa are still used today, along with Kapampangan script.

Among the earliest literature on the orthography of Visayan languages were those of Jesuit priest Ezguerra with his Arte de la lengua bisaya in 1747[17] and of Mentrida with his Arte de la lengua bisaya: Iliguaina de la isla de Panay in 1818 which primarily discussed grammatical structure.[18] Based on the differing sources spanning centuries, the documented syllabaries also differed in form.

Modern usage

Baybayin script is generally not understood in the Philippines, but the characters are still used artistically and as a symbol of Filipino heritage. Some cultural and activist groups use Baybayin versions of their acronyms alongside the use of Latin script, which is also sometimes given a baybayin-esque style. Baybayin tattoos and brush calligraphy are also popular.

It is also used in the Philippine Banknotes issued in the last quarter of 2010. The word used in the bills was "Pilipino" (ᜉᜒᜎᜒᜉᜒᜈᜓ).

Baybayin influence may also explain the preference for making acronyms from initial consonant-vowel pairs of the component words, rather than the more common use of just the first letter.

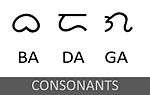

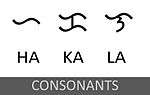

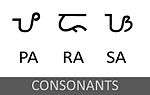

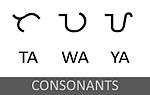

Characters

|

vowels

|

b

|

k

|

d/r

|

g

|

h

|

l

|

m

|

n

|

ng

|

p

|

s

|

t

|

w

|

y

|

Example sentences

"ᜌᜋᜅ᜔ ᜇᜒ ᜈᜄ᜔ᜃᜃᜂᜈᜏᜀᜈ᜔᜵ ᜀᜌ᜔ ᜋᜄ᜔ ᜉᜃᜑᜒᜈᜑᜓᜈ᜔᜶"

Yamáng 'di nagkaka-unawaan, ay mag paká-hinahon".

(They that have misunderstanding should stay calm.)

"ᜋᜄ᜔ᜆᜈᜒᜋ᜔ ᜀᜌ᜔ ᜇᜒ ᜊᜒᜍᜓ"

Magtanim ay 'di birò.

(Farming is not a joke.)

"ᜋᜋᜑᜎᜒᜈ᜔ ᜃᜒᜆ ᜑᜅ᜔ᜄᜅ᜔ ᜐ ᜉᜓᜋᜓᜆᜒ ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜊᜓᜑᜓᜃ᜔ ᜃᜓ"

Mámahalin kita hanggang sa pumutí ang buhok ko.

(I will love you until my hair turns white.)

Punctuation

Baybayin writing makes use of the double punctuation mark (᜶).[19]

Collation

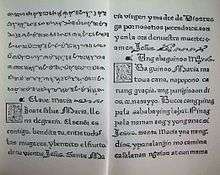

In the Doctrina Cristiana, the letters of Baybayin was collated as A O/U E/I H P K S L T N B M G D/R Y NG W[20]

In Unicode the letters are colated as A I U Ka Ga Nga Ta Da Na Pa Ba Ma Ya La Wa Sa Ha.[21]

Unicode

Baybayin was added to the Unicode Standard in March, 2002 with the release of version 3.2.

Block

The Unicode block for Baybayin, called Tagalog, is U+1700–U+171F:

| Tagalog[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+170x | ᜀ | ᜁ | ᜂ | ᜃ | ᜄ | ᜅ | ᜆ | ᜇ | ᜈ | ᜉ | ᜊ | ᜋ | ᜌ | ᜎ | ᜏ | |

| U+171x | ᜐ | ᜑ | ᜒ | ᜓ | ᜔ | |||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Representation of the character "Ra"

Although it violates the Unicode Standard,[22] U+170D is becoming the de facto standard for representing the character Ra (ᜍ), due to its use as such in commonly available Baybayin fonts.[23]

Philippines National Keyboard Layout with Baybayin

It is now possible to type Baybayin directly from the keyboard, without the need to use online typepads. The Philippines National Keyboard Layout[24] includes different sets of Baybayin layout for different keyboard users. QWERTY, Capewell-Dvorak, Capewell-QWERF 2006, Colemak, and Dvorak, all available in Microsoft Windows and GNU/Linux 32-bit and 64-bit installations.

The keyboard layout with Baybayin can be downloaded at this page.

Examples

The Lord's Prayer (Ama Namin) Post-Kudlit

: ᜀᜋ ᜈᜋᜒᜈ᜔,

- ᜐᜓᜋᜐᜎᜅᜒᜆ᜔ ᜃ,

- ᜐᜋ᜔ᜊᜑᜒᜈ᜔ ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜅᜎᜈ᜔ ᜋᜓ;

- ᜋᜉᜐᜀᜋᜒᜈ᜔ ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜃᜑᜍᜒᜀᜈ᜔ ᜋᜓ;

- ᜐᜓᜈ᜔ᜇᜒᜈ᜔ ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜎᜓᜂᜊ᜔ ᜋᜓ

- ᜇᜒᜆᜓ ᜐ ᜎᜓᜉ, ᜉᜍ ᜈᜅ᜔ ᜐ ᜎᜅᜒᜆ᜔.

- ᜊᜒᜄ᜔ᜌᜈ᜔ ᜋᜓ ᜃᜋᜒ ᜅᜌᜓᜈ᜔ ᜅ᜔ ᜀᜋᜒᜅ᜔ ᜃᜃᜈᜒᜈ᜔ ᜐ ᜀᜍᜏ᜔-ᜀᜍᜏ᜔;

- ᜀᜆ᜔ ᜉᜆᜏᜍᜒᜈ᜔ ᜋᜓ ᜃᜋᜒ ᜐ ᜀᜋᜒᜅ᜔ ᜋᜅ ᜐᜎ;

- ᜉᜍ ᜈᜅ᜔ ᜉᜄ᜔ᜉᜉᜆᜏᜇ᜔ ᜈᜋᜒᜈ᜔ ᜐ ᜋᜅ ᜈᜄ᜔ᜃᜃᜐᜎ ᜐ ᜀᜋᜒᜈ᜔;

- ᜀᜆ᜔ ᜑᜓᜏᜄ᜔ ᜋᜓ ᜃᜋᜒ ᜁᜉᜑᜒᜈ᜔ᜆᜓᜎᜓᜆ᜔ ᜐ ᜆᜓᜃ᜔ᜐᜓ,

- ᜀᜆ᜔ ᜁᜀᜇ᜔ᜌ ᜋᜓ ᜃᜋᜒ ᜐ ᜎᜑᜆ᜔ ᜅ᜔ ᜋᜐᜋ.

- [ᜐᜉᜄ᜔ᜃᜆ᜔ ᜁᜌᜓ ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜃᜑᜍᜒᜀᜈ᜔, ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜃᜉᜅ᜔ᜌᜍᜒᜑᜈ᜔, ᜀᜆ᜔ ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜃᜇᜃᜒᜎᜀᜈ᜔, ᜋᜄ᜔ᜉᜃᜌ᜔ᜎᜈ᜔ᜋᜈ᜔.]

- ᜀᜋᜒᜈ᜔/ᜐᜒᜌ ᜈᜏ.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

: ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜎᜑᜆ᜔ ᜈᜅ᜔ ᜆᜂ ᜀᜌ᜔ ᜁᜐᜒᜈᜒᜎᜅ᜔ ᜈ ᜋᜎᜌ ᜀᜆ᜔ ᜉᜈ᜔ᜆᜌ᜔ᜉᜈ᜔ᜆᜌ᜔ ᜐ ᜃᜍᜅᜎᜈ᜔ ᜀᜆ᜔ ᜃᜍᜉᜆᜈ᜔‖ ᜐᜒᜎ ᜀᜌ᜔ ᜉᜒᜈᜄ᜔ᜃᜎᜓᜂᜊᜈ᜔ ᜈᜅ᜔ ᜊᜓᜇ᜔ᜑᜒ ᜀᜆ᜔ ᜇᜉᜆ᜔ ᜋᜄ᜔ᜉᜎᜄᜌᜈ᜔ ᜀᜅ᜔ ᜁᜐᜆ᜔ᜁᜐ ᜐ ᜇᜒᜏ ᜈᜅ᜔ ᜉᜄ᜔ᜃᜃᜉᜆᜒᜍᜈ᜔‖

Motto of the Philippines

ᜋᜃᜇᜒᜌᜓᜐ᜔᜵ᜋᜃᜆᜂ᜵ᜋᜃᜃᜎᜒᜃᜐᜈ᜔᜵ᜋᜃᜊᜈ᜔ᜐ᜶

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baybayin. |

- List of India-related topics in Philippines

- Old Tagalog

- Laguna Copperplate Inscription

- Kulitan

- Hanunó'o script

- Tagbanwa alphabet

- Buhid script

- Kawi script

- Filipino orthography

- History of Indian influence on Southeast Asia

- India–Philippines relations

- Kingdom of Butuan: Indianized kingdom in Philippines

- Majapahit: Indianized empire in Philippines and Indonesia

- Srivijaya: Indianized empire in Philippines and Indonesia

References

- ↑ "Tagalog (Baybayin, Alibata)". SIL International. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Tagalog". Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Morrow, Paul. "Baybayin, the Ancient Philippine script". MTS. Retrieved September 4, 2008..

- ↑ Scott 1984, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Halili, Mc (2004). Philippine history. Rex. p. 47. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- ↑ Duka, C (2008). Struggle for Freedom' 2008 Ed. Rex. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-971-23-5045-0.

- ↑ Baybayin History, Baybayin, archived from the original on June 11, 2010, retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ↑ Archives, University of Santo Tomas, archived from the original on May 24, 2013, retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ↑ "UST collection of ancient scripts in 'baybayin' syllabary shown to public", Inquirer, retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ↑ UST Baybayin collection shown to public, Baybayin, retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ https://blog.baybayin.com/2011/03/16/baybayin-bill-national-script-act-of-2011/

- ↑ http://www.senate.gov.ph/lis/bill_res.aspx?congress=16&q=SBN-1899

- ↑ https://www.senate.gov.ph/lis/bill_res.aspx?congress=17&q=SBN-433

- ↑ Scott 1984, p. 210

- ↑ "Bahasa Melayu Kuno". Bahasa Malaysia Online Learning Resource. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ Tagalog script Archived August 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.. Accessed September 2, 2008.

- ↑ P. Domingo Ezguerra (1601–1670) (1747) [c. 1663]. Arte de la lengua bisaya de la provincia de Leyte. apendice por el P. Constantino Bayle. Imp. de la Compañía de Jesús.

- ↑ Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo de Tavera (1884). Contribución para el estudio de los antiguos alfabetos filipinos. Losana.

- ↑ "Chapter 17: Indonesia and Oceania". The Unicode Standard, Version 9.0 (PDF). Mountain View, CA: Unicode, Inc. July 2016. ISBN 978-1-936213-13-9.

- ↑ "Doctrina Cristiana". Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1700.pdf

- ↑ The Unicode Standard, Version 6.2.0 (PDF). Mountain View, CA: The Unicode Consortium. September 2012. p. 69.

- ↑ "Modern Alphabet and Baybayin -Final Version | Flickr - Photo Sharing". Flickr.

- ↑ "Philippines National Keyboard Layout". The Hæven of John™.

- Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the study of Philippine History. New Day Publishers. ISBN 971-10-0226-4.

External links

- House Bill 160, aka National Script Act of 2011

- Ang Baybayin by Paul Morrow

- Unicode Tagalog Range 1700-171F (in PDF)

- Yet another Baybayin chart

- Baybayin online translator

- Baybayin video tutorial

- Baybayin Unicode Keyboard Layout for Mac OSX

- JC John Sese-Cuneta's Baybayin Unicode Typepad

- Philippines National Keyboard Layout with Baybayin, for Microsoft Windows and GNU/Linux both 32-bit and 64-bit

- Baybayin Keyboard extension for ChromeOS (Chromebooks)

- Online Baybayin Library

- 1st Baybayin mobile translator application

- Nordenx's Baybayin Unicode Typepad

- Sinaunang baybayin

Font downloads

- Badlit Script

- Baybayin Modern Fonts

- Christian Cabuay's Baybayin Brush Font

- Paul Morrow's Baybayin Fonts

- Tagalog – Unicode character table