Enantioselective synthesis

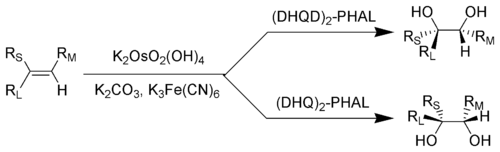

Key: RL = Largest substituent; RM = Medium-sized substituent; RS = Smallest substituent

Enantioselective synthesis, also called chiral synthesis or asymmetric synthesis,[1] is a form of chemical synthesis. It is defined by IUPAC as: a chemical reaction (or reaction sequence) in which one or more new elements of chirality are formed in a substrate molecule and which produces the stereoisomeric (enantiomeric or diastereoisomeric) products in unequal amounts.[2]

Put more simply: it is the synthesis of a compound by a method that favors the formation of a specific enantiomer or diastereomer.

Enantioselective synthesis is a key process in modern chemistry and is particularly important in the field of pharmaceuticals, as the different enantiomers or diastereomers of a molecule often have different biological activity.

Overview

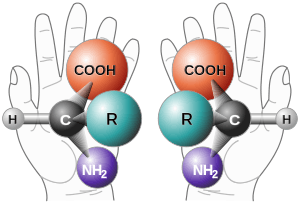

Many of the building blocks of biological systems, such as sugars and amino acids, are produced exclusively as one enantiomer. As a result of this living systems possess a high degree of chemical chirality and will often react differently with the various enantiomers of a given compound. Examples of this selectivity include:

- Flavour: the artificial sweetener aspartame has two enantiomers. L-aspartame tastes sweet, yet D-aspartame is tasteless[3]

- Odor: R-(–)-carvone smells like spearmint yet S-(+)-carvone, smells like caraway.[4]

- Drug effectiveness: the antidepressant drug Citalopram is sold as a racemic mixture. However, studies have shown that only the (S)-(+) enantiomer is responsible for the drug's beneficial effects.[5][6]

- Drug safety: D‑penicillamine is used in chelation therapy and for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. However L‑penicillamine is toxic as it inhibits the action of pyridoxine, an essential B vitamin.[7]

As such enantioselective synthesis is of great importance; but it can also be difficult to achieve. Enantiomers possess identical enthalpies and entropies, and hence should be produced in equal amounts by an undirected process – leading to a racemic mixture. The solution is to introduce a chiral feature which will promote the formation of one enantiomer over another via interactions at the transition state. This is known as asymmetric induction and can involve chiral features in the substrate, reagent, catalyst or environment[8] and works by making the activation energy required to form one enantiomer lower than that of the opposing enantiomer.[9]

Asymmetric induction can occur intramolecularly when given a chiral starting material. This behaviour can be exploited, especially when the goal is to make several consecutive chiral centres to give a specific enantiomer of a specific diastereomer. An aldol reaction, for example, is inherently diastereoselective; if the aldehyde is enantiopure, the resulting aldol adduct is diastereomerically and enantiomerically pure.

Approaches

Enantioselective catalysis

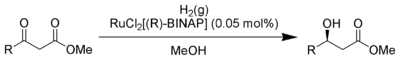

In general, enantioselective catalysis (known traditionally as asymmetric catalysis) refers to the use of chiral coordination complexes as catalysts. This approach is very commonly encountered, as it is effective for a broader range of transformations than any other method of enantioselective synthesis. The catalysts are typically rendered chiral by using chiral ligands, however it is also possible to generate chiral-at-metal complexes using simpler achiral ligands.[10] Most enantioselective catalysts are effective at low concentrations[11][12] making them well suited to industrial scale synthesis; as even exotic and expensive catalysts can be used affordably.[13] Perhaps the most versatile example of enantioselective synthesis is asymmetric hydrogenation, which is able to reduce a wide variety of functional groups.

With only 75 natural metals in existence (and not all of these showing extensive catalytic activities) the design of new catalysts is very much dominated by the development of new classes of ligands. Certain ligands, often referred to as 'privileged ligands', have been found to be effective in a wide range of reactions; examples include BINOL, Salen and BOX. However, most catalysts are rarely general, requiring certain functional groups in the substrate to form the transition state complex correctly: arbitrary structures cannot be used. For example, Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation with BINAP/Ru requires a β-ketone, although another catalyst, BINAP/diamine-Ru, widens the scope to α,β-olefins and aromatics.

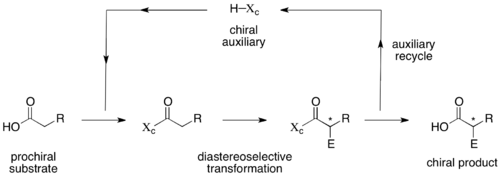

Chiral auxiliaries

A chiral auxiliary is an organic compound which couples to the starting material to form new compound which can then undergo enantioselective reactions via intramolecular asymmetric induction.[14][15] At the end of the reaction the auxiliary is removed, under conditions that will not cause racemization of the product.[16] It is typically then recovered for future use.

Chiral auxiliaries must be used in stoichiometric amounts to be effective and require additional synthetic steps to append and remove the auxiliary. However, in some cases the only available stereoselective methodology relies on chiral auxiliaries and these reactions tend to be versatile and very well-studied, allowing the most time-efficient access to enantiomerically pure products.[15] Additionally, the products of auxiliary-directed reactions are diastereomers, which enables their facile separation by methods such as column chromatography or crystallization.

Biocatalysis

Biocatalysis makes use of biological compounds, ranging from isolated enzymes to living cells, to perform chemical transformations.[17][18] The advantages of these reagents include very high ee's and reagent specificity, as well as mild operating conditions and low environmental impact. Biocatalysts are more commonly used in industry than in academic research;[19] for example in the production of statins.[20] The high reagent specificity can be a problem however; as it often requires that a wide range of biocatalysts be screened before an effective reagent is found.

Enantioselective organocatalysis

Organocatalysis refers to a form of catalysis, where the rate of a chemical reaction is increased by an organic compound consisting of carbon, hydrogen, sulfur and other non-metal elements.[21][22] When the organocatalyst is chiral enantioselective synthesis can be achieved;[23][24] for example a number of carbon–carbon bond forming reactions become enantioselective in the presence of proline with the aldol reaction being a prime example.[25] Organocatalysis often employs natural compounds and secondary amines as chiral catalysts;[26] these are inexpensive and environmentally friendly, as no metals are involved.

Chiral pool synthesis

Chiral pool synthesis is one of the simplest and oldest approaches for enantioselective synthesis. A readily available chiral starting material is manipulated through successive reactions, often using achiral reagents, to obtain the desired target molecule. This can meet the criteria for enantioselective synthesis when a new chiral species is created, such as in an SN2 reaction.

Chiral pool synthesis is especially attractive for target molecules having similar chirality to a relatively inexpensive naturally occurring building-block such as a sugar or amino acid. However, the number of possible reactions the molecule can undergo is restricted and tortuous synthetic routes may be required (e.g. Oseltamivir total synthesis). This approach also requires a stoichiometric amount of the enantiopure starting material, which can be expensive if it is not naturally occurring.

Alternative approaches

Alternatives to enantioselective synthesis usually involve the isolation of one enantiomer from a racemic mixture by any of a number of methods. If the cost in time and money of making such racemic mixtures is low (or if both enantiomers may find use) then this approach may remain cost-effective. Common methods of separation are based around chiral resolution or kinetic resolution.

Separation and analysis of enantiomers

The two enantiomers of a molecule possess the same physical properties (e.g. melting point, boiling point, polarity etc.) and so behave identically to each other. As a result, they will migrate with an identical Rf in thin layer chromatography and have identical retention times in HPLC and GC. Their NMR and IR spectra are identical.

This can make it very difficult to determine whether a process has produced a single enantiomer (and crucially which enantiomer it is) as well as making it hard to separate enantiomers from a reaction which has not been 100% enantioselective. Fortunately, enantiomers behave differently in the presence of other chiral materials and this can be exploited to allow their separation and analysis.

Enantiomers do not migrate identically on chiral chromatographic media, such as quartz or standard media that has been chirally modified. This forms the basis of chiral column chromatography, which can be used on a small scale to allow analysis via GC and HPLC, or on a large scale to separate chirally impure materials. However this process can require large amount of chiral packing material which can be expensive. A common alternative is to use a chiral derivatizing agent to convert the enantiomers into a diastereomers, in much the same way as chiral auxiliaries. These have different physical properties and hence can be separated and analysed using conventional methods. Special chiral derivitizing agents known as 'chiral resolution agents' are used in the NMR spectroscopy of stereoisomers, these typically involve coordination to chiral europium complexes such as Eu(fod)3 and Eu(hfc)3.

The enantiomeric excess of a substance can also be determined using certain optical methods. The oldest method for doing this is to use a polarimeter to compare the level of optical rotation in the product against a 'standard' of known composition. It is also possible to perform ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy of stereoisomers by exploiting the Cotton effect.

One of the most accurate ways of determining the chirality of compound is to determine its absolute configuration by Xray Crystallography. However this is a labour-intensive process which requires that a suitable single crystal be grown.

History

Inception (1815–1905)

In 1815 the French physicist Jean-Baptiste Biot showed that certain chemicals could rotate the plane of a beam of polarised light, a property called optical activity.[27] The nature of this property remained a mystery until 1848, when Louis Pasteur proposed that it had a molecular basis originating from some form of dissymmetry,[28] with the term chirality being coined by Lord Kelvin a year later.[29] The origin of chirality itself was finally described in 1874, when Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Le Bel independently proposed the tetrahedral geometry of carbon;[30] structural models prior to this work had been two-dimensional, and van 't Hoff Le Bel theorized that the arrangement of groups around this tetrahedron could dictate the optical activity of the resulting compound.

In 1894 Hermann Emil Fischer outlined the concept of asymmetric induction;[32] in which he correctly ascribed selective the formation of D-glucose by plants to be due to the influence of optically active substances within chlorophyll. Fischer also successfully performed what would now be regarded as the first example of enantioselective synthesis, by enantioselectively elongating sugars via a process which would eventually become the Kiliani–Fischer synthesis.[33]

The first enantioselective chemical synthesis is most often attributed to Willy Marckwald, Universität zu Berlin, for a brucine-catalyzed enantioselective decarboxylation of 2-ethyl-2-methylmalonic acid reported in 1904.[31][34] A slight excess of the levorotary form of the product of the reaction, 2-methylbutyric acid, was produced; as this product is also a natural product—e.g., as a side chain of lovastatin formed by its diketide synthase (LovF) during its biosynthesis[35]—this result constitutes the first recorded total synthesis with enantioselectivity, as well other firsts (as Koskinen notes, first "example of asymmetric catalysis, enantiotopic selection, and organocatalysis").[31] This observation is also of historical significance, as at the time enantioselective synthesis could only be understood in terms of vitalism. Natural and artificial compounds were fundamentally different, it was argued, and chirality could only exist in natural compounds. Unlike Fischer, Marckwald had performed an enantioselective reaction upon an achiral, un-natural starting material, albeit with a chiral organocatalyst (as we now understand this chemistry).[31][36][37]

Early work (1905–1965)

The development of enantioselective synthesis was initially slow, largely due to the limited range of techniques available for their separation and analysis. Diastereomers possess different physical properties, allowing separation by conventional means, however at the time enantiomers could only be separated by spontaneous resolution (where enantiomers separate upon crystallisation) or kinetic resolution (where one enantiomer is selectively destroyed). The only tool for analysing enantiomers was optical activity using a polarimeter, a method which provides no structural data.

It was not until the 1950s that major progress really began. Driven in part by chemists such as R. B. Woodward and Vladimir Prelog but also by the development of new techniques. The first of these was Xray Crystallography, which was used to determine the absolute configuration of an organic compound by Johannes Bijvoet in 1951.[38] Chiral chromatography was introduced a year later by Dalgliesh, who used paper chromatography to separate chiral amino acids.[39] Although Dalgliesh was not the first to observe such separations, he correctly attributed the separation of enantiomers to differential retention by the chiral cellulose. This was expanded upon in 1960, when Klem and Reed first reported the use of chirally-modified silica gel for chiral HPLC chromatographic separation.[40]

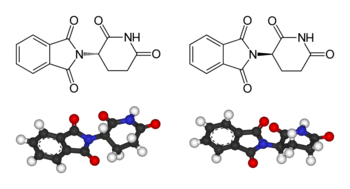

Left: (S)-thalidomide

Right: (R)-thalidomide

Thalidomide

While it had long been known that the different enantiomers of a drug could have different activities,[41][42] this was not accounted for in early drug design and testing. However following the thalidomide disaster the development and licensing of drugs changed dramatically.

First synthesized in 1953, thalidomide was widely prescribed for morning sickness from 1957 to 1962, but was soon found to be seriously teratogenic,[43] eventually causing birth defects in more than 10,000 babies. The disaster prompted many counties to introduce tougher rules for the testing and licensing of drugs, such as the Kefauver-Harris Amendment (U.S.) and Directive 65/65/EEC1 (E.U.).

Early research into the teratogenic mechanism, using mice, suggested that one enantiomer of thalidomide was teratogenic while the other possessed all the therapeutic activity. This theory was later shown to be incorrect and has now been superseded by a body of research. However it raised the importance of chirality in drug design, leading to increased research into enantioselective synthesis.

Modern Age (since 1965)

The Cahn–Ingold–Prelog priority rules (often abbreviated as the CIP system) were first published in 1966; allowing enantiomers to be more easily and accurately described.[44][45] The same year saw first successful enantiomeric separation by gas chromatography[46] an important development as the technology was in common use at the time.

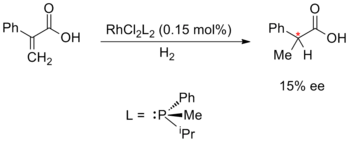

Metal catalysed enantioselective synthesis was pioneered by William S. Knowles, Ryōji Noyori and K. Barry Sharpless; for which they would receive the 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Knowles and Noyori began with the development of asymmetric hydrogenation, which they developed independently in 1968. Knowles replaced the achiral triphenylphosphine ligands in Wilkinson's catalyst with chiral phosphine ligands. This experimental catalyst was employed in an asymmetric hydrogenation with a modest 15% enantiomeric excess. Knowles was also the first to apply enantioselective metal catalysis to industrial-scale synthesis; while working for the Monsanto Company he developed an enantioselective hydrogenation step for the production of L-DOPA, utilising the DIPAMP ligand.[47][48][49]

|

| |

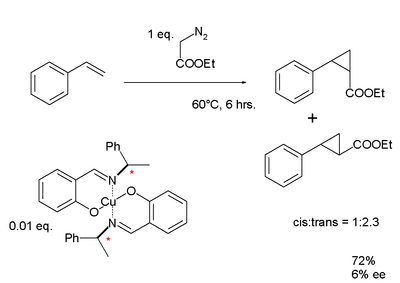

| Knowles: Asymmetric hydrogenation (1968) | Noyori: Enantioselective cyclopropanation (1968) |

|---|

Noyori devised a copper complex using a chiral Schiff base ligand, which he used for the metal-carbenoid cyclopropanation of styrene.[50] In common with Knowles' findings, Noyori's results for the enantiomeric excess for this first-generation ligand were disappointingly low: 6%. However continued research eventually led to the development of the Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation reaction.

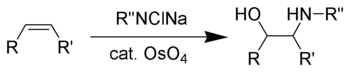

Sharpless complemented these reduction reactions by developing a range of asymmetric oxidations (Sharpless epoxidation,[51] Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation,[52] Sharpless oxyamination[53]) during the 1970s to 1980's. With the asymmetric oxyamination reaction, using osmium tetroxide, being the earliest.

During the same period, methods were developed to allow the analysis of chiral compounds by NMR; either using chiral derivatizing agents, such as Mosher's acid,[54] or europium based shift reagents, of which Eu(DPM)3 was the earliest.[55]

Chiral auxiliaries were introduced by E.J. Corey in 1978[56] and featured prominently in the work of Dieter Enders. Around the same time enantioselective organocatalysis was developed, with pioneering work including the Hajos–Parrish–Eder–Sauer–Wiechert reaction. Enzyme-catalyzed enantioselective reactions became more and more common during the 1980s,[57] particularly in industry,[58] with their applications including asymmetric ester hydrolysis with pig-liver esterase. The emerging technology of genetic engineering has allowed the tailoring of enzymes to specific processes, permitting an increased range of selective transformations. For example, in the asymmetric hydrogenation of statin precursors.[20]

See also

- Aza-Baylis–Hillman reaction, for the use of a chiral ionic liquid in enantioselective synthesis.

- Spontaneous absolute asymmetric synthesis, the synthesis of chiral products from achiral precursors and without the use of optically active catalysts or auxiliaries. It is relevant to the discussion homochirality in nature.

- Tacticity, a property of polymers which originates from enantioselective synthesis

References

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "asymmetric synthesis".

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "stereoselective synthesis".

- ↑ Gal, Joseph (2012). "The Discovery of Stereoselectivity at Biological Receptors: Arnaldo Piutti and the Taste of the Asparagine Enantiomers-History and Analysis on the 125th Anniversary". Chirality. 24 (12): 959–976. doi:10.1002/chir.22071. PMID 23034823.

- ↑ Theodore J. Leitereg; Dante G. Guadagni; Jean Harris; Thomas R. Mon; Roy Teranishi (1971). "Chemical and sensory data supporting the difference between the odors of the enantiomeric carvones". J. Agric. Food Chem. 19 (4): 785–787. doi:10.1021/jf60176a035.

- ↑ Lepola U, Wade A, Andersen HF (May 2004). "Do equivalent doses of escitalopram and citalopram have similar efficacy? A pooled analysis of two positive placebo-controlled studies in major depressive disorder". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 19 (3): 149–55. doi:10.1097/01.yic.0000122862.35081.cd. PMID 15107657.

- ↑ Hyttel, J.; Bøgesø, K. P.; Perregaard, J.; Sánchez, C. (1992). "The pharmacological effect of citalopram resides in the (S)-(+)-enantiomer". Journal of Neural Transmission. 88 (2): 157–160. doi:10.1007/BF01244820. PMID 1632943.

- ↑ JAFFE, IA; ALTMAN, K; MERRYMAN, P (Oct 1964). "THE ANTIPYRIDOXINE EFFECT OF PENICILLAMINE IN MAN.". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 43: 1869–73. doi:10.1172/JCI105060. PMC 289631

. PMID 14236210.

. PMID 14236210. - ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "asymmetric induction".

- ↑ Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart; Wothers, Peter (2001). Organic Chemistry (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.Page 1226

- ↑ Bauer, Eike B. (2012). "Chiral-at-metal complexes and their catalytic applications in organic synthesis". Chemical Society Reviews. 41 (8): 3153–67. doi:10.1039/C2CS15234G. PMID 22306968.

- ↑ N. Jacobsen, Eric; Pfaltz, Andreas; Yamamoto, Hisashi (1999). Comprehensive asymmetric catalysis 1-3. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 9783540643371.

- ↑ M. Heitbaum; F. Glorius; I. Escher (2006). "Asymmetric Heterogeneous Catalysis". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 45 (29): 4732–4762. doi:10.1002/anie.200504212. PMID 16802397.

- ↑ Asymmetric Catalysis on Industrial Scale, (Blaser, Schmidt), Wiley-VCH, 2004.

- ↑ Roos, Gregory (2002). Compendium of chiral auxiliary applications. San Diego, Calif. [u.a.]: Acad. Press. ISBN 9780125953443.

- 1 2 Glorius, F.; Gnas, Y. (2006). "Chiral Auxiliaries – Principles and Recent Applications". Synthesis. 12 (12): 1899–1930. doi:10.1055/s-2006-942399.

- ↑ Evans, D. A.; Helmchen, G.; Rüping, M. (2007). "Chiral Auxiliaries in Asymmetric Synthesis". In Christmann, M. Asymmetric Synthesis – The Essentials. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. pp. 3–9. ISBN 978-3-527-31399-0.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Biocatalysis".

- ↑ Faber, Kurt (2011). Biotransformations in organic chemistry a textbook (6th rev. and corr. ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783642173936.

- ↑ Schmid, A.; Dordick, J. S.; Hauer, B.; Kiener, A.; Wubbolts, M.; Witholt, B. (2001). "Industrial biocatalysis today and tomorrow". Nature. 409 (6817): 258–268. doi:10.1038/35051736. PMID 11196655.

- 1 2 Müller, Michael (7 January 2005). "Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Building Blocks for Statin Side Chains". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44 (3): 362–365. doi:10.1002/anie.200460852.

- ↑ Berkessel, A.; Groeger, H. (2005). Asymmetric Organocatalysis. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-30517-3.

- ↑ Special Issue: List, Benjamin (2007). "Organocatalysis". Chem. Rev. 107 (12): 5413–5883. doi:10.1021/cr078412e.

- ↑ Gröger, Albrecht Berkessel; Harald (2005). Asymmetric organocatalysis – from biomimetic concepts to applications in asymmetric synthesis (1. ed., 2. reprint. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-30517-3.

- ↑ Dalko, Peter I.; Moisan, Lionel (15 October 2001). "Enantioselective Organocatalysis". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 40 (20): 3726–3748. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20011015)40:20<3726::AID-ANIE3726>3.0.CO;2-D.

- ↑ Notz, Wolfgang; Tanaka, Fujie; Barbas, Carlos F. (1 August 2004). "Enamine-Based Organocatalysis with Proline and Diamines: The Development of Direct Catalytic Asymmetric Aldol, Mannich, Michael, and Diels−Alder Reactions". Accounts of Chemical Research. 37 (8): 580–591. doi:10.1021/ar0300468. PMID 15311957.

- ↑ Bertelsen, Søren; Jørgensen, Karl Anker (2009). "Organocatalysis—after the gold rush". Chemical Society Reviews. 38 (8): 2178–89. doi:10.1039/b903816g. PMID 19623342.

- ↑ Lakhtakia, A. (ed.) (1990). Selected Papers on Natural Optical Activity (SPIE Milestone Volume 15). SPIE.

- ↑ Pasteur, L. (1848). "Researches on the molecular asymmetry of natural organic products, English translation of French original, published by Alembic Club Reprints (Vol. 14, pp. 1–46) in 1905, facsimile reproduction by SPIE in a 1990 book".

- ↑ Pedro Cintas (2007). "Tracing the Origins and Evolution of Chirality and Handedness in Chemical Language". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (22): 4016–4024. doi:10.1002/anie.200603714. PMID 17328087.

- ↑ van't Hoff, Jacobus (September 1874). "Voorstel tot Uitbreiding der Tegenwoordige in de Scheikunde gebruikte Structuurformules in de Ruimte, benevens een daarmee samenhangende Opmerking omtrent het Verband tusschen Optisch Actief Vermogen en chemische Constitutie van Organische Verbindingen (A suggestion looking to the extension into space of the structural formulas at present used in chemistry. And a note upon the relation between the optical activity and the chemical constitution of organic compounds)" (PDF). Archives neerlandaises des sciences exactes et naturelles. (9): 445–454.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Koskinen, Ari M.P. (2013). Asymmetric synthesis of natural products (Second ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 17, 28–29. ISBN 1118347331.

- ↑ Fischer, Emil (1 October 1894). "Synthesen in der Zuckergruppe II". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 27 (3): 3189–3232. doi:10.1002/cber.189402703109.

- ↑ Fischer, Emil; Hirschberger, Josef (1 January 1889). "Ueber Mannose. II". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 22 (1): 365–376. doi:10.1002/cber.18890220183.

- ↑ Marckwald, W. (1904). "Ueber asymmetrische Synthese". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 37: 349–354. doi:10.1002/cber.19040370165.

- ↑ Campbell, Chantel D.; Vederas, John C. (23 June 2010). "Biosynthesis of lovastatin and related metabolites formed by fungal iterative PKS enzymes". Biopolymers. 93 (9): 755–763. doi:10.1002/bip.21428.

- ↑ Much of this early work was published in German, however contemporary English accounts can be found in the papers of Alexander McKenzie, with continuing analysis and commentary in modern reviews such as Koskinen (2012).

- ↑ McKenzie, Alexander (1 January 1904). "CXXVII.Studies in asymmetric synthesis. I. Reduction of menthyl benzoylformate. II. Action of magnesium alkyl haloids on menthyl benzoylformate". J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 85: 1249. doi:10.1039/CT9048501249.

- ↑ BIJVOET, J. M.; PEERDEMAN, A. F.; van BOMMEL, A. J. (1951). "Determination of the Absolute Configuration of Optically Active Compounds by Means of X-Rays". Nature. 168 (4268): 271–272. doi:10.1038/168271a0.

- ↑ Dalgliesh, C. E. (1952). "756. The optical resolution of aromatic amino-acids on paper chromatograms". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 3940. doi:10.1039/JR9520003940.

- ↑ Klemm, L.H.; Reed, David (1960). "Optical resolution by molecular complexation chromatography". Journal of Chromatography A. 3: 364–368. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(01)97011-6.

- ↑ Cushny, AR (2 November 1903). "Atropine and the hyoscyamines-a study of the action of optical isomers". The Journal of Physiology. 30 (2): 176–94. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1903.sp000988. PMC 1540678

. PMID 16992694.

. PMID 16992694. - ↑ Cushny, AR; Peebles, AR (13 July 1905). "The action of optical isomers: II. Hyoscines". The Journal of Physiology. 32 (5–6): 501–10. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1905.sp001097. PMC 1465734

. PMID 16992790.

. PMID 16992790. - ↑ Mcbride, W.G. (1961). "THALIDOMIDE AND CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES". The Lancet. 278 (7216): 1358. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)90927-8.

- ↑ Robert Sidney Cahn; Christopher Kelk Ingold; Vladimir Prelog (1966). "Specification of Molecular Chirality". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 5 (4): 385–415. doi:10.1002/anie.196603851.

- ↑ Vladimir Prelog; Günter Helmchen (1982). "Basic Principles of the CIP-System and Proposals for a Revision". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 21 (8): 567–583. doi:10.1002/anie.198205671.

- ↑ Gil-Av, Emanuel; Feibush, Binyamin; Charles-Sigler, Rosita (1966). "Separation of enantiomers by gas liquid chromatography with an optically active stationary phase". Tetrahedron Letters. 7 (10): 1009–1015. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)70231-0.

- ↑ Vineyard, B. D.; Knowles, W. S.; Sabacky, M. J.; Bachman, G. L.; Weinkauff, D. J. (1977). "Asymmetric hydrogenation. Rhodium chiral bisphosphine catalyst". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 99 (18): 5946–5952. doi:10.1021/ja00460a018.

- ↑ Knowles, William S. (2002). "Asymmetric Hydrogenations (Nobel Lecture)". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41 (12): 1998. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020617)41:12<1998::AID-ANIE1998>3.0.CO;2-8.

- ↑ Knowles, W. S. (March 1986). "Application of organometallic catalysis to the commercial production of L-DOPA". Journal of Chemical Education. 63 (3): 222. doi:10.1021/ed063p222.

- ↑ H. Nozaki; H. Takaya; S. Moriuti; R. Noyori (1968). "Homogeneous catalysis in the decomposition of diazo compounds by copper chelates: Asymmetric carbenoid reactions". Tetrahedron. 24 (9): 3655–3669. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91998-2.

- ↑ Katsuki, Tsutomu; Sharpless, K. Barry (1980). "The first practical method for asymmetric epoxidation". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 102 (18): 5974–5976. doi:10.1021/ja00538a077.

- ↑ Jacobsen, Eric N.; Marko, Istvan.; Mungall, William S.; Schroeder, Georg.; Sharpless, K. Barry. (1988). "Asymmetric dihydroxylation via ligand-accelerated catalysis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 110 (6): 1968–1970. doi:10.1021/ja00214a053.

- ↑ Sharpless, K. Barry; Patrick, Donald W.; Truesdale, Larry K.; Biller, Scott A. (1975). "New reaction. Stereospecific vicinal oxyamination of olefins by alkyl imido osmium compounds". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 97 (8): 2305–2307. doi:10.1021/ja00841a071.

- ↑ J. A. Dale, D. L. Dull and H. S. Mosher (1969). "α-Methoxy-α-trifluoromethylphenylacetic acid, a versatile reagent for the determination of enantiomeric composition of alcohols and amines". J. Org. Chem. 34 (9): 2543–2549. doi:10.1021/jo01261a013.

- ↑ Hinckley, Conrad C. (1969). "Paramagnetic shifts in solutions of cholesterol and the dipyridine adduct of trisdipivalomethanatoeuropium(III). A shift reagent". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 91 (18): 5160–5162. doi:10.1021/ja01046a038. PMID 5798101.

- ↑ Ensley, Harry E.; Parnell, Carol A.; Corey, Elias J. (1978). "Convenient synthesis of a highly efficient and recyclable chiral director for asymmetric induction". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 43 (8): 1610–1612. doi:10.1021/jo00402a037.

- ↑ Sariaslani, F.Sima; Rosazza, John P.N. (1984). "Biocatalysis in natural products chemistry". Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 6 (6): 242–253. doi:10.1016/0141-0229(84)90125-X.

- ↑ Wandrey, Christian; Liese, Andreas; Kihumbu, David (2000). "Industrial Biocatalysis: Past, Present, and Future". Organic Process Research & Development. 4 (4): 286–290. doi:10.1021/op990101l.