Sankt Julian

| Sankt Julian | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Sankt Julian | ||

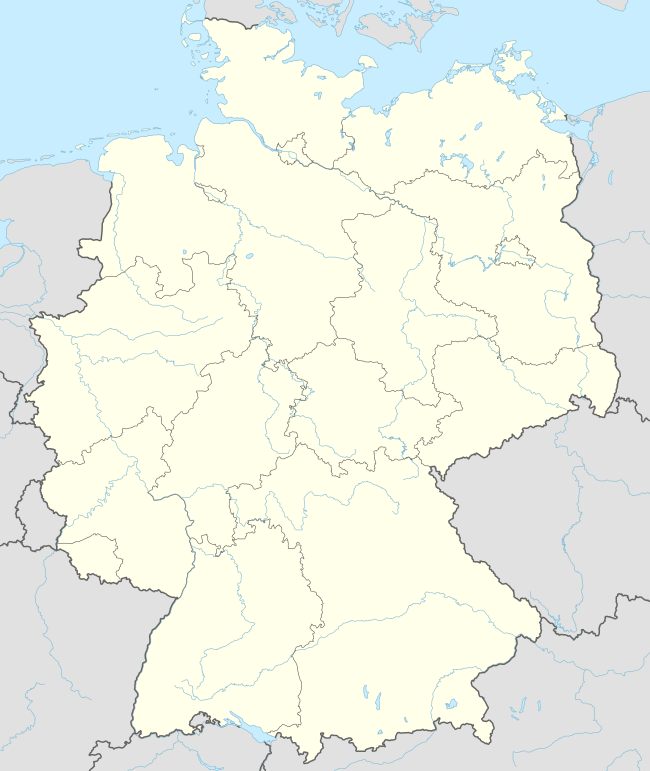

Location of Sankt Julian within Kusel district  | ||

| Coordinates: 49°36′29.44″N 7°30′42.34″E / 49.6081778°N 7.5117611°ECoordinates: 49°36′29.44″N 7°30′42.34″E / 49.6081778°N 7.5117611°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| District | Kusel | |

| Municipal assoc. | Lauterecken-Wolfstein | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Hans Werner Mensch | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 14.07 km2 (5.43 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 1,097 | |

| • Density | 78/km2 (200/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 66887 | |

| Dialling codes | 06387 | |

| Vehicle registration | KUS | |

| Website | www.sankt-julian.de | |

Sankt Julian (often rendered St. Julian) is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Kusel district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde Lauterecken-Wolfstein.

Geography

Location

The municipality lies on the river Glan in the Western Palatinate.

The municipality’s main centre, likewise called Sankt Julian, lies in the Glan valley, mainly on the river’s left bank and on both sides of Bundesstraße 420, while over on the right bank, a new, smaller neighbourhood has arisen. Also standing there are the school, the kindergarten and the Museumsmühle (“Museum Mill”). Formerly running through the village was the Glantalbahn (railway), but service was permanently ended on this stretch of the line in 1992. Sankt Julian’s nominal limits reach from the fertile cropfields in the Glan valley up to the heights either side of the river. Some 300 ha of its traditional area of 1 407 ha now lies within the Baumholder troop drilling ground. Elevations range from 190 m above sea level on the valley floor up to 463 m above sea level at the Ottskopf in the so-called Schwarzland.[2]

The outlying centre of Eschenau lies downstream from the Steinalb’s mouth on the Glan’s left bank on a point bar at 180 m above sea level in its lowest spots, and roughly 250 m above sea level in its higher ones. North of this centre, the land climbs steeply up to the heights, which stand almost 400 m above sea level. The other side of the Glan with the buildings of the former Schrammenmühle (a mill) belongs to the former (before the amalgamation) municipal area of Gumbsweiler, itself now part of Sankt Julian, like Eschenau. Some two kilometres up the Glan lies Niederalben’s outlying centre of Neuwirtshaus, and just beyond that is Rathsweiler. About one kilometre down the Glan lies Sankt Julian’s like-named main centre, and across the Glan to the southeast lies another of Sankt Julian’s centres, Gumbsweiler.[3]

Gumbsweiler lies in a hollow in the middle Glan valley on the river’s right bank right near the municipality’s other centres of Sankt Julian and Eschenau at an elevation of roughly 180 m above sea level. Elevations outside the built-up area reach more than 350 m above sea level: the Hubhöhe (364 m), the Großer Mayen (352 m), the Wackerhübel (321 m). The Schrammenmühle with five houses lies some 1.5 km up the Glan and can best be reached from the left bank by way of the constituent community of Eschenau. The Pilgerhof (“Pilgrim’s Estate”) lies some 4 km from the centre on the southern edge of the Freudenwald (“Joy Forest”). This was built in 1964-1965 as an Aussiedlerhof (an agricultural settlement established after the Second World War to increase food production). Gumbsweiler’s area measures 435 ha, of which 67 ha is cropland, 172 ha is grassland, 155 ha is wooded and 63 ha is settled [sic].[4]

Obereisenbach, Sankt Julian’s fourth centre, lies apart from the others some 250 m above sea level on the upper reaches of the Eisenbach (also called the Kesselbach), which empties into the Glan near Glanbrücken’s outlying centre of Niedereisenbach. The mountains either side of the narrow brook valley climb up to 400 m above sea level. Only a few hundred metres up from this centre runs the boundary with the Baumholder troop drilling ground.[5]

Neighbouring municipalities

Sankt Julian borders in the north on the municipality of Kirrweiler, in the northeast on the municipality of Deimberg, in the east on the municipality of Glanbrücken, in the southeast on the municipality of Horschbach, in the south on the municipality of Welchweiler, in the southwest on the municipality of Ulmet, in the west on the municipality of Niederalben and in the northwest on the Baumholder troop drilling ground. Sankt Julian also meets the municipality of Bedesbach at a single point in the south.

Constituent communities

Sankt Julian’s Ortsteile are the main centre, likewise called Sankt Julian, Eschenau, Gumbsweiler and Obereisenbach. Under many of the headings in this article, each of the four centres will be treated separately, as their histories and backgrounds are on many points quite different from each other. The municipality of Sankt Julian is not so much a village as an amalgamation of four historically separate villages, which were only united into one political body in relatively recent times.[6][7][8][9]

Municipality’s layout

Sankt Julian (main centre)

The village’s appearance is characterized by its topography. A linear village (by some definitions, a “thorpe”) sprang up in the valley along the river’s left bank, later spreading out to the hillside along two sidestreets. The neighbourhood around the church can be considered the village’s hub. Prehistoric archaeological finds have shown that the area was already settled in La Tène times and on into Roman times. As a pilgrimage centre and seat of the Vierherrengericht (“Four-Lord Court”), the village was said to be a central place in the Glan valley, and to this day it can still claim a certain central placement. The formerly self-administering municipality of Sankt Julian had a great municipal area that bordered on the fields of neighbouring Eschenau, Niederalben, Obereisenbach and Niedereisenbach on the Glan’s left bank, while on the right bank it bordered on Gumbsweiler, Welchweiler, Horschbach and Hachenbach. These limits can be explained by the village’s mediaeval history. Sankt Julian, Eschenau, Obereisenbach and Niederalben (along with the vanished villages of Ohlscheid, Hunhausen and Grorothisches Gericht) quite likely had a jointly held woodland and a common, splitting these up among themselves only in the course of time. All this explains the tangle of municipal boundaries. In 1905 these villages’ municipal areas together still spread over 1 856 ha of land, matching the area occupied by the old Vierherrengericht. Still belonging today to Sankt Julian’s municipal area is a 327-hectare uninhabited area called the “Schwarzland” (“Blackland”) which was incorporated into the Baumholder troop drilling ground in the 1930s when the Nazis established it, and which has now formally been transferred back to the municipality. Over on the Glan’s right bank, the formerly self-administering municipality of Sankt Julian had parts of its municipal area. They bordered on the Lenschbach, which formerly marked the border between lands held by the Waldgraves and those held by the Duchy of Palatinate-Zweibrücken. Some rural cadastral toponyms, for instance “Pfaffental” (meaning roughly “Parson’s Dale”), still recall a time when Sankt Julian was an important pilgrimage place, and perhaps also the seat of a monastery. The municipal area was worked on into the 20th century by small agricultural landholds that busied themselves with grain growing, livestock raising, fruitgrowing and, on a small scale, winegrowing. A few bigger farms had between 10 and 20 hectares, while most others were quite small, with some 3 or 4 hectares. In the 19th century, the growing population overstretched the available agricultural land and farmers began looking for other opportunities for a livelihood, with many of them resorting to emigration. Today there are only a few farmers, and modern agriculture in Sankt Julian, as in all other villages in the Glan valley, only offers earning opportunities for a few operations.[10]

Eschenau

Bundesstraße 420 also runs through Sankt Julian’s constituent community of Eschenau, on which, towards Sankt Julian, stand the buildings of a former industrial concern. On the north side on the way into the village lies the graveyard. Branching off Bundesstraße 420 in Eschenau are two notable village streets. One runs southwards to the Glan. At the end stands the former railway station, in which today the painter Dietmar E. Hofmann maintains a permanent art exhibition, calling the old station the Kleiner Kunstbahnhof (“Little Art Railway Station”). Likewise standing on this street is the former schoolhouse, which has since been converted into a village community centre. The other street branches off northwards and mainly serves a new building zone. Farmhouses called Einfirsthäuser (“single-roof-ridge houses”), which are typical of the Westrich, an historic region that encompasses areas in both Germany and France, stand in the area near the intersections. In the village’s west end the Schrammenmühle (a mill) can be reached over a bridge across the Glan. The former railway line, now used by draisine-pedalling tourists, crosses the Glan near the station and then turns towards the former Sankt Julian station.[11]

Gumbsweiler

The houses in Gumbsweiler’s original built-up area stand safe from flooding at the foot of the Kleine Höhe (“Little Heights”) and near the bridge crossing. Until the 20th century, the Glan flooded regularly, especially when the Steinalb fed vast amounts of water into it, and the river’s course changed time and again. In a later phase of settlement, the even north slope of the heights was settled. Thus arose an irregular, thin village with open strip fields. Houses and outbuildings were as a rule built with only a single floor. Only after measures had been undertaken to control the Glan, and after the railway embankment had been built did people once again risk occupying the lands near the water. A roadway parallel to the Glan formed and four sidestreets branched off towards the mountain slope. All streets, however, led to the bridge. The village church stands there, as do the gristmill and the village limetree. The crossroads up from the mill has been since days of old the gathering point for villagers and youth. In 1905, the village streets were still lit with oil lamps. Only in 1921 were the village and its houses linked to the electricity grid. The great shift in the village’s appearance and modernization of the houses, though, was brought by the building of the central watermain in 1954 and the laying of sewerage in 1984-1987. The houses had floors added onto them, sanitary fittings were installed, washing machines became available and heating systems were brought up to date. The village streets, too, were sealed to make them suitable for modern traffic, and also expanded and properly lit. Gumbsweiler’s nominal area stretches between the Glan and the Grundbach to the Hubhöhe (heights) and to the woodland known as the Großes Mayen. It is thus very hilly and has many slopes, more shady north slopes than sunny south slopes. The soils are sandy, loamy and stony, and the depths are mainly slaty clay-marl beds. They are not very fertile and have been ranked on a quality scale at 37 points out of 100. Furthermore, there is the dearth of precipitation. The plots were quite small and broadly scattered. The village lies in the northern strip of its nominal area, meaning that farmers often had to walk up to 2 km to and from their plots, along with equipment drawn by horses, oxen or even cows. Tractors only began to appear after 1950. The heights are used for cropraising while the meadows down in the dale and the slopes are used for grazing or fruitgrowing. The Freudenwald is the biggest continuous woodland. In the years from 1972 to 1979, “classic” Flurbereinigung was undertaken. This laid the groundwork for one farming operation that was run as a main income-earning business and five others that were run as secondary occupations. Through leaseholds, farms of more than 50 ha were created. Twenty-five hectares of new forest was planted. In the cadastral area called “Saupferch”, a landscaped pond with a shooting clubhouse and a grilling pavilion appeareed in 1982. The country lanes were expanded to almost 50 km. Eight kilometres of these were paved with blacktop.[12]

Obereisenbach

As of 2005, Obereisenbach is made up of 28 houses, most of which stand on the brook’s left bank. In the village’s upper end, a short street with a few houses on it branches off towards the west mountain slope. Before this junction stands the former schoolhouse, which is now a private house. Up from the village, towards the Baumholder troop drilling ground, stands the former Bitschenmühle, while another mill stood down from the village. Their buildings nowadays serve as private houses. Between the lower mill and the beginning of the built-up area lies the graveyard. The village inn, which is sometimes visited by a great many daytrippers, stands in the village’s upper end. The former workshops and commercial buildings at the former quarry on the Reuterrech, the slope on the dale’s left side, have been converted into a hunting lodge and now serve to entertain many hunting guests.[13]

History

Antiquity

Sankt Julian (main centre)

The settled area around Sankt Julian is very old. On the bed of the Lenschbach in the 1950s, two jade hatchets were found and determined to be from the New Stone Age, and thus some 5,000 years old. In the cadastral area of Schwarzland about 1938, two urn graves from La Tène times (450 BC) were unearthed along with a blue glass ring as grave goods. The old churchtower shows some Roman spolia. It could be that the church was built on the same site as an earlier Roman temple, and it is therefore easy to see that the builders would have salvaged bits of this old building for the church. When the church was given a new nave in 1874, Roman spolia from the old nave were saved. At first, these were kept in the churchtower before being transferred to the Historisches Museum der Pfalz (“Historical Museum of the Palatinate”) in Speyer in 1970. Casts of these spolia now adorn the wallwork at the steps that lead into the church. They depict a hippocamp and they come from a Roman tomb. This mythical creature is hitched to a sea god’s chariot. Other Roman spolia are found in the churchtower’s wallwork. Also among the finds have been two Amazon shields, as they are customarily found on pedestals at Mithraea.[14] Further bearing witness to a Roman presence are Roman soldiers’ and traders’ graves along with gold coins from Emperor Constantine’s time.[15]

Eschenau

The broader area around Eschenau was settled in prehistoric times, bearing witness to which, among other things, are hammerstones from the Stone Age, which have also turned up in neighbouring municipalities. Further prehistoric and also Roman archaeological finds have come to light in neighbouring Sankt Julian and Gumbsweiler.[16] Coins and bricks found near Eschenau show that there was a settlement at what is now greater Sankt Julian as long ago as AD 360.[17]

Gumbsweiler

A prehistoric barrow, about which there were once reports, is now no longer to be found. Of particular interest, however, are the finds of two little stone hatchets, which might date from the New Stone Age, although on the other hand they might also be of Roman origin. One of these finds was owned by Friedrich W. Weber and is today kept at the Kusel district administration. It is a trapezoidal hatchet blade made of jade with a wholly intact edge and workmanship that shows masterful skill in grinding and polishing. It was found in the bed of the Grundbach. Another stone hatchet of similar quality was found near the graveyard and is today still in private ownership. While digging work was being done at the Klosterflur (rural cadastral area), workers struck some old walling made of limestone mortar, some thick bits of tile and a great number of potsherds and artefacts from Roman times. A Gallo-Roman settlement likely stood here, which may have some link with the Roman finds in neighbouring Sankt Julian. Furthermore, a sewer made of stone slabs, open at the top and leading to the Grundbach was also struck. The village’s farmers are always telling of building blocks being brought up by their ploughs in the fields, and of light stripes seen running across the earth in their seeded fields in times of drought. It could mean that a Gallo-Roman villa rustica lies buried underneath, or perhaps a monasterial estate from the early days of the so-called Remigiusland.[18]

Obereisenbach

Graves found within Obereisenbach’s nominal area point to settlers in the area in prehistoric times. On the heights west of the village, some land surveyors found a silex blade, which is now kept at the Historisches Museum der Pfalz (“Historical Museum of the Palatinate”) in Speyer. In the formerly municipally unassigned cadastral area of Schwarzland northwest of Obereisenbach, nowadays part of the Baumholder troop drilling ground, cable layers unearthed two flat graves which also yielded up beakers, dishes, pots and a glass ring. It was most likely a cremation grave at which the bodies were burnt on site. Roman archaeological finds have been unearthed mainly in neighbouring Sankt Julian and Gumbsweiler. A Roman bronze statue – an idol – was found by a farmer while he was ploughing. This figure is now kept in Munich. Roman potsherds have also turned up near Obereisenbach.[19]

Middle Ages

Sankt Julian (main centre)

It is unknown when the tower that still stands now at the old Romanesque church in Sankt Julian was built, but going by its stylistic elements, it might have been sometime about the turn of the 12th century. It is highly likely that an earlier church once stood on this same spot. About 1290, a priest named Conrad worked in Sankt Julian, a well-to-do man who endowed a chapel to hold Saint Juliana’s relics, which was built right next to the then Romanesque church. Furthermore, Conrad bequeathed to the village a great landhold. After the chapel was built, Sankt Julian must have grown into a pilgrimage centre. In the Middle Ages, there was in the Rhinegravial lands between the rivers Glan and Nahe an entity known as the Hochgericht auf der Heide (“High Court on the Heath”), within which the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves exercised high jurisdiction. This high court was further divided into smaller court districts, among which was the Vierherrengericht (“Four-Lord Court”), whose seat was in Sankt Julian. In 1424, the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves enfeoffed a Count Johann vom Steine with the village, while a Hugelin vom Steine (perhaps Count Johann’s brother) had already been enfeoffed with the neighbouring village of Obereisenbach (now a constituent community of Sankt Julian) and with a mill at Sankt Julian itself.[20]

Eschenau

Eschenau lay in the Nahegau, and was likely founded only in the 11th or 12th century. An exact date has never been determined. According to the 1340 document that contains Eschenau’s first documentary mention, Eschenau was granted to the Lords of Montfort, then represented by Sophie of Monfort. She was obliged to pay a tithe through the Church of Sankt Julian to the monastery on the Remigiusberg amounting to two Malter of wheat, two Malter of corn (possibly meaning rye), four Malter of oats and six Logel of wine. The payments might well have been missed for several years. Sophie then showed herself ready to comply with the requirements. According to a 1366 document, though, the Church of Sankt Julian now had some paying of its own to do. Sophie was now ready to take on half the tithe payments, while the provost was now to pay the other half. Territorially, Eschenau then belonged to the Vierherrengericht (“Four-Lord Court”) of Sankt Julian within the Hochgericht auf der Heide (“High Court on the Heath”). The responsible feudal lords were the Lords of Steinkallenfels, the Lords of Kyrburg (Kirn) and the Rhinegraves of Grumbach. Eschenau was nevertheless time and again transferred by the territorial lords to subordinate castle lords and officials. While in the 14th century the village was held by the Lords of Montfort, in the late 15th century it passed in equal shares to Heinrich of Ramberg, Emerich of Löwenstein and Rudolf of Alben. On the other hand, personages from Eschenau can be named who were in foreign service, such as the young nobleman Kunz von Eschenau, who served the town of Kaiserslautern in 1477, and Ludwig von Eschenau, who about 1544 was an Amtmann in Meisenheim and later in Bergzabern, and also an Palatinate Großhofmeister.[21]

Gumbsweiler

Going by the village’s name, ending as it does in —weiler, Gumbsweiler might have been founded early in the time when the Franks were taking over the land. At that time, it lay within the so-called Remigiusland around Kusel and Altenglan, which in the early 12th century was taken over by the Counts of Veldenz as a Vogtei. Gumbsweiler, however, only had its first documentary mention in 1364 in a document from Count Heinrich of Veldenz. The count’s son, who later became Heinrich III of Veldenz, was married to Lauretta (or Loretta) of Sponheim, and the young couple had chosen as their residence Castle Lichtenberg. Every village in the Unteramt of Altenglan/Ulmet was obliged by this document to supply them both with their economic needs. The document thus named all the villages in question. In a 1379 document, the knight Sir Mohr of Sötern acknowledged that, among other things, he had been enfeoffed with holdings in Gumbsweiler (Gundeßwilr) by Count Friederich of Veldenz. Nevertheless, the name Gundeßwilr that appears in this document has been ascribed by other regional historians, Carl Pöhlmann among them,[22] not to Gumbsweiler, but rather to the village of Ginsweiler. In 1444, the County of Veldenz met its end when Count Friedrich III of Veldenz died without a male heir. His daughter Anna wed King Ruprecht’s son Count Palatine Stephan. By uniting his own Palatine holdings with the now otherwise heirless County of Veldenz – his wife had inherited the county, but not her father’s title – and by redeeming the hitherto pledged County of Zweibrücken, Stephan founded a new County Palatine, as whose comital residence he chose the town of Zweibrücken: the County Palatine – later Duchy – of Palatinate-Zweibrücken.[23]

Obereisenbach

An exact founding date for Obereisenbach cannot be determined. Like Eschenau, Obereisenbach lay in the Nahegau, whose counts split into several lines, and at the time of its 1426 first documentary mention, the village belonged to the Lords of Steinkallenfels (or Stein-Kallenfels) in the Hochgericht auf der Heide (“High Court on the Heath”) and, more locally, the Vierherrengericht (“Four-Lord Court”), whose seat was in nearby Sankt Julian. A 1336 document about Niedereisenbach spoke of an inferiori Ysenbach, thus of a lesser place of this name, there might well have been a greater village as well, with the same name.[24]

Modern times

Sankt Julian (main centre)

In the 16th century, the Waldraves and Rhinegraves pledged their holding here to Palatinate-Zweibrücken under the duke at that time, Wolfgang, but the pledge was redeemed in 1559. After a legal dispute, the village passed to Steinkallenfels in 1628. High jurisdiction at first remained in the Waldraves’ and Rhinegraves’ hands, but in 1680, this, too, was ceded to the Lords of Steinkallenfels. In 1778, the Steinkallenfels sideline died out, and Sankt Julian was taken back by the Waldraves and Rhinegraves.[25]

Eschenau

The 16th century was a time of constant change in Eschenau. In 1502, the village was still under Hans von Ramberg’s ownership, but by 1554 it was held by the Prince of Stromberg – whose wife was Annette von Ramberg. Thereafter it passed into the Mauchenheims’ ownership, and then Philipp Franz gave it back to the Waldraves and Rhinegraves of Grumbach. In 1596, these counts bought many of their fiefs back from those whom they had enfeoffed, and until the French Revolution, Eschenau, too, belonged directly to the Rhinegraviate. Time and again, Ludwig von Eschenau, already mentioned above, was named in documents. He was a ministerialis in the service of the Duchy of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, and, obviously, he was from Eschenau. He negotiated between Palatinate-Zweibrücken and the Palatinate in 1534 over the redemption of a series of pledged villages in Alsace. In 1535, he negotiated in a dispute about church property in Einöd and Ernstweiler, and also led negotiations in a dispute with the County of Leiningen. In 1536 he settled a dispute between Palatinate-Zweibrücken and the Palatinate about the community of Gutenberg. Then, he had to deal once again with a dispute involving Einöd and Ernstweiler. Already in 1541, Ludwig became Amtmann in Meisenheim and was significantly involved with the formulation of the Treaty of Disibodenberg, which laid out measures for Palatinate-Zweibrücken’s behaviour should the Palatinate’s Electoral line die out. In 1543, the guidelines were finally laid down for founding the Palatinate-Veldenz sideline. In 1544 he was Amtmann of Neu-Kastell and led negotiations for Gräfenstein. In 1553 he appeared in the record as Großhofmeister of the Palatinate. During the Thirty Years' War, the village shared a fate with all neighbouring villages when it was utterly destroyed. It appeared for the first time under the name Ischenaw on a map of the Theatrum Europäum, on which the so-called Battle of Brücken is depicted. In the late 17th century, there was further destruction as a result of French King Louis XIV’s wars of conquest. Details are unknown. The 18th century ushered in a time of steady population growth, and there was emigration, mainly to North America.[26]

Gumbsweiler

Gumbsweiler lay within Palatinate-Zweibrücken, and also within an Unteramt, which was administered for a while from Altenglan, next from the vanished village of Brücken (not to be confused with Brücken, which still exists), and then from Ulmet. In 1546, Duke Wolfgang approved the expansion of Heinrich Kolb’s mill by two grist runs on the proviso that the estate mill at Ulmet not have any business taken away from it. The mill must therefore already have been standing a long time by then. In this time, too, a tithe barn was built in the village, whose buildings lasted centuries, only to be torn down in 1978 in the name of village renewal. A keystone with the yeardate 1604 chiselled into it has been preserved. Political development did not always proceed harmoniously. Heavy setbacks came with the Thirty Years' War, by whose end Gumbsweiler had become uninhabited and uninhabitable, although the little late mediaeval church was left mostly unscathed. After the recovery, the Nine Years' War (known in Germany as the Pfälzischer Erbfolgekrieg, or War of the Palatine Succession) brought further setbacks, and only in the 18th century did steady population growth begin. In 1724, the bridge across the Glan at Gumbsweiler had fallen into disrepair. It was torn down and a new one was built. This was later partly demolished by French troops, and then given a provisional repair before being built yet again in 1841.[27]

Obereisenbach

During the time of the Plague, the Thirty Years' War and French King Louis XIV’s wars of conquest, Obereisenbach shared its neighbours’ fate. There were deaths from both sickness and wartime ravages. The responsible lordship was still Steinkallenfels until Count Philipp Heinrich’s death in 1778. Then came a disagreement between the Counts of Salm-Salm (Hunoltstein), the Counts of Salm-Kyrburg and the Rhinegraves at Grumbach over who owned the two villages of Sankt Julian and Obereisenbach. The dispute was eventually settled in the Rhinegraves’ favour, but they were considered the overlords anyway.[28]

Recent times

Sankt Julian (main centre)

In the time of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era that followed, Sankt Julian belonged to the Mairie (“Mayoralty”) of Offenbach, the Canton of Grumbach, the Arrondissement of Birkenfeld and the Department of Sarre. While in the new territorial order arising from the Congress of Vienna the old Rhinegravial villages on the Glan’s left bank were grouped into the Principality of Lichtenberg, a newly created exclave of the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (which as of 1826 became the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha), Sankt Julian, Obereisenbach and Eschenau were excepted from this transfer and grouped into the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1817 as part of an exchange against a village in the Oster valley. Sankt Julian at first became the seat of a Bürgermeisterei (“mayoralty”) for these three villages, and administratively amalgamated with it in this context was neighbouring Obereisenbach. The merged municipality was called Sankt Julian-Obereisenbach. The mayoralty was united with the one in Ulmet in 1861, but became separate again in 1887. In 1878, a new church was built. In this rural community with a goodly share of workers among its population, there was a noticeable shift towards polarization of political groupings in the wake of the First World War. Quite early on, the Nazi Party (NSDAP) gained a strong foothold in Sankt Julian, winning 29.8% of the vote locally in May 1924 Reichstag election (today, the Social Democratic Party of Germany is said to be the village’s strongest political party). By 1938, after the Third Reich had existed for five years and war was coming, the Heeresstraße (literally “Army Road”) was built. Since the Second World War ended, Sankt Julian has been part of the then newly founded state of Rhineland-Palatinate. In 1966, the new schoolhouse was dedicated. In the course of the 1968 administrative restructuring in Rhineland-Palatinate, the mayoralty was dissolved and the villages of Sankt Julian-Obereisenbach, Eschenau and Gumbsweiler were amalgamated to form the greater municipality of Sankt Julian, which since 1972 has belonged to the Verbandsgemeinde of Lauterecken. In 1985, passenger traffic on the local Altenglan-Lauterecken railway line was ended, and in 1992, the line was closed outright.[29]

Eschenau

After French Revolutionary troops marched in about 1794, the old territorial structures were swept away. Once the German lands on the Rhine’s left bank were annexed to France, new administrative entities arose based on the French Revolutionary model. They were set up in 1797, and were made permanent in 1801 (although actually, they did not last very long). Eschenau, just like Sankt Julian, belonged to the Mairie (“Mayoralty”) of Offenbach, the Canton of Grumbach, the Arrondissement of Birkenfeld and the Department of Sarre. The states that were allied against France (Prussia, Austria and Russia), reconquered the German lands on the Rhine’s left bank in 1814. After a two-year transitional period, Eschenau passed to the Kingdom of Bavaria in a departure from what was generally considered the new border arrangements, with the Glan downstream from the mouth of the Steinalb generally being held to be the border between Bavaria and Prussia (or until 1834 the Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Principality of Lichtenberg). This exceptional arrangement, which also affected Sankt Julian and Obereisenbach, was part of an exchange against a village in the Oster valley. Sankt Julian at first became the seat of a Bürgermeisterei (“mayoralty”) together with Eschenau and Obereisenbach. The merged municipality was called Sankt Julian-Obereisenbach. The mayoralty was united with the one in Ulmet in 1861, but became separate again in 1887. Late in the Second World War, in 1945, part of Eschenau was destroyed in an attack by American strafers. There were dead and wounded. In the course of the 1968 administrative restructuring in Rhineland-Palatinate, the mayoralty was dissolved and the villages of Sankt Julian-Obereisenbach, Eschenau and Gumbsweiler were amalgamated to form the greater municipality of Sankt Julian, which since 1972 has belonged to the Verbandsgemeinde of Lauterecken.[30]

Gumbsweiler

The French Revolution and the French annexation from 1797 to 1815 brought with it its horrors, but also some advantages: the lasting abolition of serfdom, commercial freedom, the elimination of water rights and milling rights formerly held by feudal lords, freedom from inheritance taxation and, of course, the abolition of all lordly privileges. The new freedoms brought the people advantages foremost in the economic field of endeavour, especially when it came to building new mills. Gumbsweiler belonged during Revolutionary, and later Napoleonic, times to the Mairie (“Mayoralty”) of Hundheim, the Canton of Lauterecken, the Arrondissement of Kaiserslautern and the Department of Mont-Tonnerre (or Donnersberg in German), whose seat lay at Mainz. The Mairie of Hundheim became a mayoralty under Bavarian administration beginning in 1816, and for a while, Gumbsweiler was the biggest place within it. According to Mahler, writing in 1966, “The Bürgermeisterei (“Mayoralty”) of Hundheim at first belonged to the so-called Kreisdirektion Kaiserslautern (“Kaiserslautern District Directorate”), but then after the formation of the Landkommissariate (“State Commissariates”) in 1817 was assigned to the Landkommissariat of Kusel. In 1838, the Rheinkreis (that is, the Palatinate when it was a Bavarian exclave), whose seat was in Speyer, received the official designation “Regierungsbezirk Pfalz”. In 1862, the Landkommissariate became Bezirksämter, and in 1938, Landratsämter.” During this Bavarian epoch, Gumbsweiler grew from a small farming village into a bigger village among whose dwellers, bit by bit, workers came to dominate. Apart from the changes in higher levels of government (Kingdom of Bavaria, Free State of Bavaria, state of Rhineland-Palatinate), the administrative arrangements at first did not change. In the early 1930s, the Nazi Party (NSDAP) became very popular in Gumbsweiler. In the 1930 Reichstag elections, 11.3% of the local votes went to Adolf Hitler’s party, but by the time of the 1933 Reichstag elections, after Hitler had already seized power, local support for the Nazis had swollen to 54.2%. Hitler’s success in these elections paved the way for his Enabling Act of 1933 (Ermächtigungsgesetz), thus starting the Third Reich in earnest. The village itself came through the Second World War unscathed, but the memorial at the graveyard lists 51 fallen. In the course of administrative restructuring in 1968, Gumbsweiler lost its autonomy with the founding of the new Ortsgemeinde of Sankt Julian with the constituent communities (Ortsteile) of Eschenau, Gumbsweiler, Obereisenbach and Sankt Julian.[31]

Obereisenbach

Obereisenbach’s administrative situation after the French Revolutionary annexation was the same as Eschenau’s and Sankt Julian’s: it belonged to the Mairie (“Mayoralty”) of Offenbach, the Canton of Grumbach, the Arrondissement of Birkenfeld and the Department of Sarre. The states that were allied against France (Prussia, Austria and Russia), reconquered the German lands on the Rhine’s left bank in 1814. After a two-year transitional period, Obereisenbach passed to the Kingdom of Bavaria in a departure from what was generally considered the new border arrangements, with the Glan downstream from the mouth of the Steinalb generally being held to be the border between Bavaria and Prussia (or until 1834 the Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Principality of Lichtenberg). This exceptional arrangement, which also affected Sankt Julian and Eschenau, was part of an exchange against a village in the Oster valley. Sankt Julian at first became the seat of a Bürgermeisterei (“mayoralty”) together with Eschenau and Obereisenbach. The merged municipality was called Sankt Julian-Obereisenbach. The mayoralty was united with the one in Ulmet in 1861, but became separate again in 1887. Just after the Second World War, there was an armed confrontation with some French occupational troops, who had been mistaken by the populace for “plundering Russians” who had been forced labourers, now freed, in the only just ended time of the Third Reich. The shooting killed one inhabitant from Obereisenbach. In 1958, a watermain was built in the village. In the course of administrative restructuring in 1968, the Bürgermeisterei of Sankt Julian was dissolved, and in 1972, within the Verbandsgemeinde of Lauterecken, Sankt Julian became the hub of the like-named Ortsgemeinde with the constituent communities (Ortsteile) of Eschenau, Gumbsweiler, Obereisenbach and Sankt Julian.[32]

Population development

Sankt Julian (main centre)

Information about Sankt Julian’s population levels before 1800 is not available. In 1828, the village had 471 inhabitants, of whom 432 were Protestant, 36 Jewish and 3 Catholic. In the century that followed, the population level rose only slightly. In 1997 there were 593 inhabitants, of whom 537 were Evangelical and 42 Catholic. Since the persecution during the time of the Third Reich, there have no longer been any Jews in the village.

The following table shows population development over the centuries for Sankt Julian and Obereisenbach together, with some figures broken down by religious denomination:[33]

| Year | 1825 | 1835 | 1871 | 1905 | 1939 | 1961 |

| Total | 467 | 530 | 600 | 652 | 643 | 724 |

| Catholic | 3 | 37 | ||||

| Evangelical | 434 | 684 | ||||

| Jewish | 30 | – | ||||

| Other | – | 3 |

Eschenau

Eschenau has remained rurally structured to this day. The greater part of the population worked until a few decades ago at agriculture. Alongside farmers, though, there were also farm workers, forestry workers and craftsmen. In the village itself ran an industrial concern that employed both villagers and others. This, however, no longer exists. With respect to religion, the villagers are overwhelmingly Evangelical. Today, Eschenau is a residential community for many commuters. The village’s population rose steadily over the last two centuries with a temporary pause about the turn of the 20th century, and now is stagnating once again, with a drop in numbers foreseen for the coming years.

The following table shows population development over the centuries for Eschenau, with some figures broken down by religious denomination:[34]

| Year | 1825 | 1835 | 1871 | 1905 | 1939 | 1961 |

| Total | 155 | 189 | 215 | 216 | 240 | 258 |

| Catholic | – | 7 | ||||

| Evangelical | 144 | 247 | ||||

| Jewish | 11 | – | ||||

| Other | – | 4 |

Gumbsweiler

Gumbsweiler was home to many farmers, though very early on there were also workers living in the village, and today they make up the majority. There is generally a good cohesion among the villagers, who always seem ready to solve issues communally. There is great interest locally in playing music.

The following table shows population development over the centuries for Gumbsweiler, with some figures broken down by religious denomination:[35]

| Year | 1825 | 1835 | 1871 | 1905 | 1939 | 1961 | 1975 | 1997 |

| Total | 298 | 365 | 390 | 491 | 595 | 564 | 508 | 470 |

| Catholic | 38 | 19 | ||||||

| Evangelical | 260 | 541 |

Obereisenbach

Obereisenbach’s inhabitants lived well into the 20th century mainly from agriculture, although there were also the miller families, innkeepers, distillers, workers – especially at the stone quarries – and those who ran the mineral water spring. Rounding out the scene were the basket weavers who travelled overland plying their wares, some very poor people, often families with many children but also lone persons who eked out a living in substandard dwelling conditions. This population structure has since undergone a thorough shift. Farming is indeed still practised, but most people, who belong to the most varied of occupations, seek their livelihoods elsewhere. Obereisenbach is popular among seniors and pensioners as a second residence. With respect to religion, the villagers are overwhelmingly Evangelical. The population grew over the course of the 19th century, but shrank again in the 20th. Despite the more recent gains towards the end of the century, a drop in numbers is foreseen for the coming years.

The following table shows population development over the centuries for Obereisenbach:[36]

| Year | 1833 | 1871 | 1907 | 1910 | 1925 | 1971 | 2000 |

| Total | 63 | 90 | 108 | 103 | 100 | 75 | 88 |

Municipality’s names

Sankt Julian

Sankt Julian was mentioned in a 1290 document as “apud Sanctam Julianam” (Latin for “at Saint Juliana’s”), and therefore, despite the name’s masculine appearance and sound, the village is in fact named after a saint named Juliana, who is worshipped at the village’s church. There are several saints named Juliana, but the old patronage for Sankt Julian’s church could only have referred to Juliana of Nicomedia, who during her long martyrdom had molten lead poured over her. According to a falsified document dated to 1192, “Saint Julien” might have been the church’s namesake saint, and indeed the village maintains a partnership with one of the many places in France named Saint-Julien (to wit, the one in Côte-d’Or). Sankt Julian may well once have borne another name that the brisk pilgrimage in Saint Juliana’s pushed aside when the name was changed. If so, the old name is now forgotten. After 1290, the following forms of the name crop up in the record: ecclesiae sanctae Julianae (1336), ecclesiae de sancta Juliana (1340), zu sant Juliana (14th century), Sanct Julian (1588) and Sanct Juljan (1686). In the local speech, the village is also called “Dilje”.[37]

Eschenau

The name appeared for the first time in cartularies kept by the County of Veldenz. In 1340 it appeared as Essenoe and in 1366 as Eschenawe. The current name first appeared in an original document in 1614. The name originally described a settlement on a floodplain (Aue in German) with ash trees (Eschen in German) growing on it.[38]

Gumbsweiler

The village’s name, Gumbsweiler, has the common German placename ending —weiler, which as a standalone word means “hamlet” (originally “homestead”), to which is prefixed a syllable Gumbs—. Most of the villages with names ending in —weiler arose in the early period of the Frankish takeover of the land. The Old High German word villare might relate to the village’s founder’s name. Perhaps the prefix arose from a personal name, Gummund, suggesting that the village arose from a homestead founded by an early Frankish settler named Gummund, thus “Gummund’s Homestead”. The name first appeared in Count Heinrich’s document mentioned above in 1364 in the form Gommerswijlre. Other forms that the name has taken have been, among others, Gumeswilre (14th century), Gummeßwilre (1416), Gomßwillr (1458) and Gumbsweiller (1593).[39]

Obereisenbach

Obereisenbach was named for the brook that flows by it, the Eisenbach (“Ironbrook”), and the prefix is German for “upper”, distinguishing it from Niedereisenbach (“Nether Ironbrook”), which lies at the brook’s mouth. The name first cropped up in the record in the form Oberysenbach daz dorff und Geriechte (modernized: Obereisenbach das Dorf und Gericht, meaning “Obereisenbach the village and court [district]”) in a 1426 document. The reference to iron in the village’s name is inspired by the iron inclusions in the local sandstone.[40]

Vanished villages

Within what are now Eschenau’s limits once lay two villages named Haunhausen (mentioned in 1287) and Olscheid (mentioned in 1345). Their exact locations are unknown. Olscheid lay roughly at the limits with the fellow Sankt Julian constituent community of Obereisenbach and the separate municipality of Niederalben. It might even be that these former places lay within Niederalben’s limits. According to researchers Dolch and Greule, two now vanished villages once stood within Gumbsweiler’s limits, named Borrhausen and Trudenberg. About the former almost nothing is known; the village’s name is preserved only as a rural cadastral toponym. The latter crops up in the historical record only once, in Count Heinrich’s 1364 document (see above), which dealt with supplying the young comital couple Heinrich and Lauretta, and which mentioned many placenames for the first time, including Gumbsweiler. It is certain that Trudenberg lay on the Glan’s right bank within the former Remigiusland, likely on the heights between Ulmet and Gumbsweiler. Could it be that the local forest’s current name, “Freudenwald”, is a corruption of an earlier name “Trudenberger Wald”, after the now vanished village? Trudenberg might also have lain within Ulmet’s current limits. Within what are now Obereisenbach’s limits once lay a place called Berghausen, but the only record of this place is the preservation of its name in rural cadastral toponyms. This village’s exact location, too, is unknown. It might have lain within what were Sankt Julian’s limits before the four constituent communities were amalgamated.[41][42][43]

Religion

Sankt Julian (main centre)

As already stated in the History section above, Sankt Julian was a well known pilgrimage centre in the Middle Ages. In Saint Michael’s Chapel (Michaeliskapelle) next to the church, Saint Juliana’s relics were worshipped. The originally Romanesque nave was replaced in 1878 with a Gothic Revival structure. The old Romanesque churchtower has been preserved. Also during the Middle Ages, Sankt Julian was a parish seat, and belonging to the parish were not only the villages of the Vierherrengericht (“Four-Lord Court”), but also Niedereisenbach and Offenbach, as well as a few villages that lay within what is now the Baumholder troop drilling ground. The pastor of Sankt Julian was also the vicar at the Offenbach Monastery. That brought along consequences in the time after the Reformation when the Steward of Offenbach wanted to force Sankt Julian’s pastor into the Zweibrücken Church Order, even though he was a Rhinegravial subject. The problem was settled only after the French Revolution, when Sankt Julian had become Bavarian. Both the County Palatine of Zweibrücken and the Rhinegraviate adopted the Lutheran faith early on in the time of the Reformation. Under the old principle of cuius regio, eius religio, everybody in Sankt Julian had to convert to Protestantism sometime about 1560, and even today, now that there is freedom of religion, the great majority of Sankt Julian’s inhabitants are Evangelical. Sankt Julian suffered great losses in the Thirty Years' War, but was spared the ravages of French King Louis XIV’s wars of conquest. In 1694, the church partly burnt down. The fire damage was repaired in 1698 and 1699, and Baroque stylistic elements now characterized the church. The little pilgrimage chapel was torn down in 1776. The 19th century brought further serious changes to the building. The nave was replaced in 1880-1881 with a new Classicist one, while the mediaeval churchtower was preserved.[44]

Eschenau

It is likely that Eschenau was from the beginning tightly bound with the Church of Sankt Julian. In 1556, the Waldgravial-Rhinegravial House of Grumbach introduced the Reformation, and the Lutheran faith prevailed until the 1818 Palatine Union. Calvinist and Catholic Christians never grew to important numbers. Originally, church services were held only in Sankt Julian, but as early as the 19th century they were also held at specified times at the schoolhouse in Eschenau. The Catholics attended church services in Offenbach. It is likely that already in the 18th century, as well as on into the 19th century, roughly 10% of the inhabitants belonged to the Jewish faith. This can be explained by the many Jewish tradesmen who often plied their trades unlawfully in the Duchy of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, and who thus liked to settle right at the duchy’s borders.[45]

Gumbsweiler

Before the time of the Reformation, Gumbsweiler belonged under ecclesiastical organization to the Archbishopric of Mainz. The little village church was first mentioned in 1573, and even then, it might already have been almost one hundred years old. More locally, the village belonged to the parish whose seat was at the likewise Zweibrücken neighbouring village of Ulmet, which also in the Early Middle Ages could not be reached without crossing the river. About 1537, the Dukes of Zweibrücken introduced the Reformation along Lutheran lines. However, beginning in 1588, Count Palatine Johannes I forced all his subjects to convert to Reformed belief as espoused by John Calvin. Only in 1820 was Gumbsweiler parochially united with Sankt Julian. Gumbsweiler’s church came through the Thirty Years' War unscathed but was burnt out in King Louis XIV’s wars of conquest, leaving only the outer walls standing. In 1720, the duchy authorized a reconstruction, and the municipality even had money to acquire two bells. In the meantime, Lutherans had once again settled in the village, for after the Thirty Years' War, the principle of cuius regio, eius religio no longer applied. In 1723, five Lutheran families settled in Gumbsweiler. During the 18th century, there were disputes between Calvinists and Lutherans. An ordinance from the Zweibrücken Supreme Consistory allowed the Lutherans to share the church. Similar disputes arose about church usage between the Presbytery and the Catholics living in the dale, represented by their leadership, Heinrich Greiner from Lauterecken. The Catholics considered the church a simultaneum and deemed shared usage to be a right, which in 1857 Pastor Schwab from Sankt Julian had denied them. This led to a court case before the Royal Regional Court at Kaiserslautern. The judge’s ruling set forth in law that the Gumbsweiler Protestant church community was the little church’s sole owner, with its bells and fixtures, and that therefore it alone could avail itself of the church’s use. There were no further modifications to the church building. A decision in 1913 to tear the little church down so that a bigger one could be built was reversed in 1919. By this time, the building had ended up, along with fixtures, in miller Johann Adam Schlemmer’s ownership. The two old bells fell victim to the ravages of time. The 8.5 m-high ridge turret received a bronze bell in 1930, delivered by the firm Pfeifer from Kaiserslautern. Cracks in the foundations and walls made a renovation sorely necessary to prevent the church from caving in. In the years 1966-1968, the little church was thoroughly restored, inside and out. The tower was made 17 m taller, and new pews were built. In 1986, the peal of bells became more complete with the addition of a third bell.[46]

Obereisenbach

From a religious point of view, Obereisenbach was from the beginning tightly bound to the Church of Sankt Julian. The village’s dead were buried until 1930 at Sankt Julian’s graveyard. From the Reformation, the Lutheran faith prevailed until the Protestants forged the Palatine Union in 1818. The Catholics attend church services in Offenbach. Little is known about immigrants’ religious practices.[47]

Politics

Municipal council

The council is made up of 16 council members, who were elected by proportional representation at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman. The 16 seats on council are shared by two voters’ groups.[48]

Mayor

Sankt Julian’s mayor is Hans Werner Mensch, and his deputies are Holger Weber and Susanne Linn.[49]

Coat of arms

The municipality’s arms might be described thus: Argent a pile reversed throughout gules charged with a waterwheel spoked of four Or issuant from a fess abased wavy of the field, dexter a pot azure and issuant from sinister an abbot’s staff of the same surmounting per saltire an ash leaf proper.

The charges in the arms refer to all four of the municipality’s constituent communities. The waterwheel and the wavy fess (or “water”) is a reference to the geography and history, indicating that the municipality lies on the Glan and that there were mills (and in one case there still is) in the municipality. The pot refers to Saint Juliana’s martyrdom, while the abbot’s staff refers to Gumbsweiler’s former allegiance to the Remigiusland, which was a monastic holding. The ash leaf relates to Eschenau. The tinctures chosen for the arms were the ones once borne by the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves.[50] Before the four centres now making up the municipality of Sankt Julian were amalgamated, the outlying centres of Eschenau, Gumbsweiler and Obereisenbach bore no arms of their own.[51][52][53]

Town partnerships

Sankt Julian fosters partnerships with the following places:

Saint-Julien, Côte-d'Or (Burgundy), France since 1985[54]

Saint-Julien, Côte-d'Or (Burgundy), France since 1985[54]

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[55]

Sankt Julian (main centre)

- Protestant parish church, Hauptstraße 21 – Romanesque belltower, about 1130; sandstone-block aisleless church, Rundbogenstil, 1880/1881, architect Max Siebert, Speyer; furnishings, Stumm organ

- Bergstraße 3 – Protestant rectory; one-floor hewn-stone-framed plastered building, Romanesque Revival motifs, 1885, architect Joseph Hoffmann, Ludwigshafen; former parish barn

- Near Mühlstraße 8 – former oilmill; quarrystone building with half-hipped roof, renovated 1840; technical equipment

- Ortsstraße 8 – Quereinhaus (a combination residential and commercial house divided for these two purposes down the middle, perpendicularly to the street), marked 1842

- Steige 1 – former Alte Schule (“Old School”); cubic sandstone-block building with hipped roof, 1838, architect Johann Schmeisser, Kusel

- Former administration building, north of the village near Obereisenbach – with smithy and canteen, housed Reuerrech sandstone quarry’s administration, Romanesque Revival rusticated stone-block buildings with battlements, 1910

Eschenau

- Bahnhofstraße 10 – former railway station; stone-block building with jutting gable roof, separate storage shed, 1904

- Flurstraße 2 – Quereinhaus; commercial part 1852, dwelling wing on vaulted cellar 1863

Gumbsweiler

- Protestant church, Woogstraße 2 – aisleless church, essentially Gothic, alterations in Baroque style 1720

Regular events

Sankt Julian (main centre)

Each year on the second weekend in July, Sankt Julian holds its kermis (church consecration festival, locally known as the Kerb), and on the first day of Advent a Christmas market is held.[56]

Eschenau

Eschenau’s kermis is held on the fourth weekend in October. During the summer, a Wunnerfest is also held, staged by the Wunnerverein, which also stages a small rock festival called Rock im Kuhstall (“Rock in the Cowshed” – because it is held in an old barn). The story behind the club’s and the festival’s names, prefixed as both are with Wunner—, is explained below under Clubs.[57] The Wunnerfest has been held each year since 1989. It features a photographic exhibit at the schoolhouse in Eschenau, which has always met with great approval. The organizer for this is Karl Ludwig, and each year’s exhibit follows a theme, for example “Eschenau over Changing Times”, “The Glan Valley from Altenglan to Lauterecken” or “The Municipal Ring”. The rock festival began when a young, well travelled man from Bonn came to Gumbsweiler, hoping to become a labourer in organic farming. When an opportunity arose to acquire Otto Stuber’s farm in Eschenau, he left Gumbsweiler and came to Eschenau, having in mind no longer to be a mere labourer, but rather a landowner at an organic farm. He built himself a house out of the barn with a cozy room where Eschenau youth spent many a comfortable hour. Within this young circle, the idea arose to organize and stage the first Rock im Kuhstall. To cover the cost of getting somebody to come and play the music, each of the eight youths in the circle contributed 100 DM to a kitty. The needed rock group, one called “Liquid Sky” (but not the one that now bears that name), was soon found. Also needed, though, was a major overhaul of the barn, but the youths worked together to bring this about. A local man, Hermann Mayer, also lent the use of his vaulted cellar to be used as a small bar. Despite older villagers’ misgivings, the first Rock im Kuhstall went smoothly, and the circle felt encouraged to found a club that would task itself with staging the festival every year.[58]

Gumbsweiler

The most important festival in Gumbsweiler is held to be the kermis (also locally known as the Kerb), which is held on the fourth Sunday in August and lasts three days. The kermis is the time of the Straußbuwe and Straußmäd (“bouquet lads” and “bouquet lasses”; these two words are dialectal), who spend weeks beforehand binding the “bouquet” together. A parade opens this village festival, led by a band, itself followed by the Straußbuben (standard High German for Straußbuwe) bearing the huge Strauß (“bouquet”). The Straußpfarrer (“bouquet pastor”, but not a real clergyman) climbs up a ladder and delivers the Straußrede (“bouquet speech”), which covers amusing things that have happened in the village, all in rhyme. Afterwards, the “Three Firsts” are danced (die Drei Ersten). The kermis is nowadays held under a marquee, formerly having been held at an inn, but the traditions of the Frühschoppen (morning drink) and of “dancing the wreath out” (Heraustanzen des Kranzes) have been preserved at this Zeltkerb (Zelt means “tent”). The village youth’s sometimes quite mad shenanigans on the Witching Night (Walpurgis Night, 30 April–1 May) have been waning over the years and are now only practised by schoolchildren. Nonetheless, even today, older youths still put up a mighty Maypole every year. Only in Gumbsweiler does the ancient custom of singing on Saint John’s Eve still exist. On the night of 23 to 24 June, the village youth go on a Heischegang (that is, they beg for treats, in this case mainly eggs and bacon, but other gifts too) through the village. While they do this, they also sing the Gehannsenachts-Lied, whose melody is accompanied by the noises of peening and whetting a scythe. The serenades end with the verse “Wir danken Euch für Eure Gaben. Rosarot, drei Blümlein rot, die wir von Euch empfangen haben. Sei mein lieb trautes Mädchen!” (“We thank you for your gifts. Pink, three little blossoms red, that we have received from you. Be my darling true girl!”).[59]

Obereisenbach

There was once a kermis, now no longer held, that took place on the first Sunday in July, but there is still a summer festival held on this day. In Advent, a Christmas Market is held. On 1 May, the village youths put up a Maypole.[60]

Clubs

Sankt Julian (main centre)

Active in Sankt Julian’s main centre are the following clubs:[61]

- Angelsportverein — angling club

- Feuerwehr — fire brigade

- Förderverein der Feuerwehr — fire brigade promotional association

- Frauenbund — league of women

- Freie Wählergruppe e. V. — Free Voters’ group

- Gesangverein 1873 — singing club

- Jagdgenossenschaft — hunting association

- Kirchbauverein Sankt Julian e. V. — church building club

- Krankenpflegeverein — nursing club

- Landfrauenverein — countrywomen’s club

- Obst- und Gartenbauverein — fruitgrowing and gardening club

- Ralleyclub Mittleres Glantal — rallying club

- Schäferhundeverein — sheepdog club

- SPD-Ortsverein — Social Democratic Party of Germany local chapter

- Tischtennisverein — table tennis club

- Turn- und Sportverein — gymnastic and sport club

- Wanderverein „Die Dippelbrüder“ — hiking club

Eschenau

Along with its singing club “Frohsinn” and its countrywomen’s club, Eschenau also has its Wunnerverein. As described above under Regular events, this arose from a circle of youths led by a would-be organic farmer who first conceived the idea of the yearly rock festival. The founding meeting took place on 20 January 1988. Thirty-four members registered and they chose Thomas Jung as their chairman. The club’s goal was and still is the care and furthering of the village community through sporting leisure activities, group outings, fostering contacts with other clubs and cultural events. The club was officially registered on 18 April 1988. The idea for calling the club the Wunnerverein goes back to a local folk legend, which has never been written down, but rather has been passed down from one generation to the next. According to this tale, about the turn of the 20th century, or perhaps even earlier, the Glan, as it so often had before, flooded its banks. About where the railway bridge spans the river now was a wooden footbridge linking one bank to the other. This footbridge had not been built to withstand such torrents, and the floodwaters eventually proved no match for the footbridge and tore it from its place, washing it down the Glan. This much was to be foreseen. What few would have foreseen, however, was the “wonder” (Wunder in German, or dialectally, Wunner) – or was it a deed worthy of the Schildbürgers? – of what happened next. The villagers from Eschenau sought their footbridge by setting out for Ulmet, believing that they would find it there. This was, however, hardly likely, for Ulmet lay upstream from Eschenau, and the footbridge seekers had to put up with a goodly helping of ribbing from their neighbours over this. The episode came to be known as the Eschenauer Wunner. Eschenau’s youths seized upon this old story, transferring this expression to their club, thus keeping a bit of the local lore all the more alive. The highlights since the club’s founding have been the days-long trips to Berlin, to the Lüneburg Heath along with Heligoland, to Saxon Switzerland, to Locarno on Lake Maggiore, to Oktoberfest in Munich and also to the Harz. The club also stages events for children and works on village renewal projects, among these the weathervane on the schoolhouse.[62][63]

Gumbsweiler

The Gumbsweiler singing and music club is more than 140 years old. In 1873, the men’s choir was brought into existence. It gave itself the tasks of fostering harmonious singing, promoting social life and sponsoring all cultural works. In the two world wars, it fell silent, only to be revived in 1948. An independent women’s choir was formed in 1964. The melding of the two into a mixed choir came in 1971. Joined to the club is the youth mandolin orchestra, from which also sprang an entertainment orchestra. Youths’ musical training is now once again strongly promoted. In 1970, Südwestfunk (SWF, now part of Südwestrundfunk) Baden-Baden recorded a cycle of folksongs with choir and orchestra, and in 1971 the programme Schiwago auf dem Lande (“Zhivago in the Country”) was broadcast from Mainz. The gymnastic club, founded in 1921, had to be dissolved in 1960 owing to a dearth of exercise instructors. Today, the villagers of Gumbsweiler have intensified their participation in the clubs based in Sankt Julian’s other centres.[64]

Obereisenbach

Obereisenbach has only one club, the Bürgergemeinschaft Obereisenbach (Obereisenbach Citizens’ Association), which sees to the villagers’ cohesion, village renewal and raising the quality of life.[65]

Art gallery

In Eschenau, the villagers’ cohesion defines a lively cultural life, borne mainly by the village’s clubs, but foremost in Eschenau’s cultural life is painter Dietmar E. Hofmann’s Kleiner Kunstbahnhof (“Little Art Railway Station”), which has been earning itself national importance for decades with its permanent exhibits with Hofmann’s own handiwork, which has surrealist tendencies. Catalogues of Hofmann’s most important works are available. Works can be bought in the village. At the same time, Hofmann exhibits sculptors’ works and offers them for sale.[66]

Economy and infrastructure

Economic structure

Sankt Julian (main centre)

Sankt Julian had from the beginning a rural character. Given the village’s central location, though, small businesses sprang up quite early on. Mills were built after the Thirty Years' War. In the 19th century, major quarries were opened that yielded yellow sandstone. After the Second World War, however, this industry was given up. A breadmaking plant that had long been in business was shut down, as was a window factory in neighbouring Eschenau. Many workers commute as far as Kaiserslautern, with the odd one even going as far as Ludwigshafen.[67]

Eschenau

In the time after the Second World War, the number of agricultural operations shrank, and farming is now no longer of great importance among occupations in Eschenau. Eschenau was once the seat of a major window manufacturer. There are still small businesses (a fitter’s shop and a plant nursery), and the turnover in artistic products, both painting and sculpture, is also a certain factor in the village’s economy.[68]

Gumbsweiler

Alongside domestic farms, there were in Gumbsweiler, as in almost all Glan villages, mills, each of which developed differently. The gristmill in Gumbsweiler has stood in three different places, first as the Kolbenmühle down from the Heckenacker (a rural area), then nearer the village on the other side of the Glan, and then right near the village at the bridge. This is one of the very few of these mills that are still running today. It runs as a heritage mill, but also does business. Automation and efficient production have greatly changed the mill. It is today driven by a turbine to raise its capacity. There was another mill called the Schrammenmühle, which stood about 1.5 km upstream from the village. This mill was mentioned as early as 1580, but was likely much older than that. It was where Friedrich W. Weber came from, and he compiled a few prime works about the Palatinate’s mills. In the end, this mill only ran as an oilmill. It was shut down for good in 1954. Two smaller mills stood for a time on the Grundbach. They were run in the early 19th century during French Revolutionary and Napoleonic times as coöperatives in which some 15 families held shares in each. Through the Second World War, the agricultural structure prevailed, and farming was everybody’s main livelihood. Each family had a few small plots of land for growing grain and potatoes. Fruitgrowing, too, played a great role, for pomaceous fruits were pressed and stone fruits were made into jam. The regional office (Bezirksamt) in Kusel registered in 1905 for Gumbsweiler twelve named farms that were run as primary income earners, fifteen craftsmen and businessmen, two grocery shops, two painters and two innkeepers. Income at the craft businesses was very small, and therefore even the craftsmen had to work the land, albeit as a secondary occupation. Of great importance to feeding the villagers was stockbreeding. Every house had a stable, usually an outbuilding. In 1904, Gumbsweiler counted 20 horses, 35 head of cattle, 138 pigs and 41 goats. In times of war and neediness, livestock and small-animal keeping grew so greatly that greenery had to be gathered from the woods as stable straw. As cattle farming dwindled, the number of sheep rose. Cattle at first were raised as part of dairy farming, but more and more they came to be raised for beef. During the 20th century, many Gumbsweiler villagers had to earn their livelihoods as workers. They worked at the hard-rock quarries in the dale, at the coal pits in the Saarland, at the Baumholder troop drilling ground or later, after having completed the requisite training, at the Opel works in Kaiserslautern. The village grew into a residential community for both blue- and white-collar workers who must commute to work elsewhere each day. The younger generation is moving to the cities and industrial centres. Still doing business in the village are a bakery that also sells groceries, a stonemasonry and gravestone business and an inn.[69]

Obereisenbach

While agriculture was mainly what saw to the Obereisenbach villagers’ needs, along with the two former mills, after the Second World War, the number of agricultural operations shrank. Beginning in the 19th century, other businesses afforded the villagers choices in livelihoods: quarries, businesses that filled mineral water bottles, distilleries and basket weaving. The Bitschenmühle (mill) up from the village functioned in the 18th century as an estate mill. The Bauernmühlchen (“Little Farmers’ Mill”) down from the village was maintained as a coöperative. The sandstone quarry in the Reuterrech, the slope on the dale’s left side, was from 1831 let out to private interests by the municipality, earning major importance about 1900 when the railway line along the Glan was built. The quarry remained in business until about 1960. Along with this sandstone quarry, there were also several small hard-rock quarries. Since a great deal of good fruit grew within Obereisenbach’s limits, this was made into fruit wine and spirits. The last distillery, though, closed in 2004. The mineral spring was mentioned as early as the early 16th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, the spring’s owners began to put it to commercial use. There was a spring on the river’s left bank below the Reuterrech near the big sandstone quarry, called the Sankt Julia Quelle, and another one over on the right bank called the Pfälzer Quelle. Bit by bit, three bottling businesses grew up, bottling not only mineral water but also various fruity drinks. The products were shipped to many parts of the Western Palatinate and the Saarland. After the Second World War, it was no longer financially worthwhile to continue the business. In 1970, the last bottling business ceased production. The basket weaving craft flourished in the 19th and early 20th centuries and the products were sold by travelling salesmen.[70]

Education

The greater municipality of Sankt Julian nowadays has one kindergarten and one primary school. The Realschule, vocational schools and the school for children with mental handicaps are to be found in Kusel, while the school for children with learning difficulties is located in Lauterecken.

Sankt Julian (main centre)

About the origins of schooling in Sankt Julian little is known, since all the school journals went missing at the end of the Second World War. From old property registers, however, it can be seen that already in the 17th century, the municipality owned “school land”, and therefore, there must have been a school in the village even then. Going by the village’s size, a two-class village school must have been built quite early on. The first schoolhouse stood on the branch of the path from Bergstraße (“Mountain Street”) at Haus Steige 1, near the rectory. It might have been built as early as the 17th century, but was torn down in 1850 and replaced with a bigger building, which served as the schoolhouse until about 1900. After 1945, the teachers’ dwellings and the municipal secretariat were built. The house is now under private ownership. A new schoolhouse was built about 1900 on Hauptstraße (“Main Street”). Housed here until 1973 were always two classes and the mayor’s office. This house (Hauptstraße 38) was later sold by the municipality. Housed there now are the savings bank and a dental practice. In 1962, a Sankt Julian school association was founded under which all schoolchildren in Sankt Julian, Obereisenbach, Eschenau, Gumbsweiler, Hachenbach and Rathsweiler were banded together. From the villages of Horschbach, Elzweiler and Welchweiler, only the Hauptschule students were grouped into the school association, and of those from Ulmet and, beginning only in 1968, Niederalben, only grade levels 7 to 9 were incorporated. In 1966, this school association acquired the big schoolhouse on the Lenschbach as its central school. Owing to the school reforms that were being put through at that time, though, and at the same time the administrative restructuring in Rhineland-Palatinate with the merger of many municipalities in the Regierungsbezirk of Koblenz into the Regierungsbezirk of Rheinhessen-Pfalz, there were also new requirements for founding school associations. Thus, first, in 1970, the provisional Hauptschule Offenbach-Hundheim/Sankt Julian, whose seat was in Offenbach-Hundheim, was opened. There were three grade levels there at the beginning, with grade levels 5 and 6 being taught at the new schoolhouse in Sankt Julian and levels 7 to 9 at the Offenbach-Hundheim schoolhouse. This Hauptschule was attended by students from Offenbach-Hundheim and Sankt Julian and those from Buborn, Kirrweiler, Homberg, Deimberg, Glanbrücken, Hachenbach and Wiesweiler, and in the beginning also those from a few villages in the Verbandsgemeinde of Altenglan, namely the three Hermannsberg municipalities of Horschbach, Elzweiler and Welchweiler, along with Ulmet, Niederalben and Rathsweiler. The students from the Verbandsgemeinde of Altenglan were grouped into their own Hauptschule in Altenglan in 1973. The Hauptschule in Offenbach-Hundheim was merged with the one in Lauterecken in 1975. Besides the Hauptschule, there was at first also a primary school for the schoolchildren from all Sankt Julian’s centres and Hachenbach, Niederalben and Rathsweiler besides. In 1973, a new primary school named Sankt Julian Offenbach-Hundheim was opened for the schoolchildren from Buborn, Nerzweiler, Offenbach-Hundheim, Sankt Julian and Wiesweiler. This school still stands in Sankt Julian’s main centre, and is still open.[71]

Eschenau

Until Bavarian times, there was only a winter school (a school geared towards an agricultural community’s practical needs, held in the winter, when farm families had a bit more time to spare) in Eschenau, attendance at which was optional. All-year education, however, was available in Sankt Julian. In 1837, an administrator named Adam Fegert was doing the teaching at the winter school, and promised to come back the next year – but never did. A schoolteacher named Georg Philipp Stachelrath applied, and the pastor from his home village, Merxheim, confirmed in writing that Stachelrath was indeed a teacher by trade. Nevertheless, this trained teacher left again quickly enough. It was odd, however, that winter schooling was still being maintained in Eschenau, even though Bavarian law forbade it. There came further teachers and teacher candidates, but none lasted in the job very long, until at last in 1840, all-year schooling was introduced. At that time, a schoolteacher named Schöpper, who at first could offer no references because he could not get them back from another employment application that he had made. It turned out later that Schöpper could furnish proof of very good marks, having even been rated “excellent” in religion, but he could neither sing nor play the organ. The village councillors chose to overlook Schöpper’s lack of musical ability for, after all, there was no church in Eschenau anyway. The district administration demanded, however, that the teacher sit an examination after two years’ service and have himself further trained in the artistic subjects (Schöpper could also not draw very well). Until that was done, no binding agreement was to be concluded with the teacher. Nevertheless, Schöpper was eventually named Eschenau’s permanent schoolteacher, but not until 1855, by which time he was 39 years old. He then remained in service in Eschenau until 1886, retiring at the age of 70. Schöpper had reached no mandatory retirement age, but he could no longer see and hear very well, and he was also suffering from a hernia. The yearly considerations for Schöpper’s service amounted to 137 Rhenish guilders, of which 70 guilders was paid out in cash, while 25 guilders was deducted for the school land, 10 for the dwelling, 4 for a specified amount of municipal firewood and 28 for 7 hL of corn (wheat or rye). Over the next few years, there was once again a high teacher turnover. In 1889 came Wilhelm Schmidt, who had been an administrator in Dörrenbach. He was forthwith granted a permanent post, and in 1890 the authorities granted him official leave to marry Katharina Zimmermann from Bergzabern, who had been born in the United States to a father from Germany who had been a master baker. Schmidt was efficient at his job. He received approval from the authorities to make the school barn available to a local fertilizer manufacturer, and he himself was allowed to take part in selling the products. He then participated at an agency of the Giselaverein, a club named after a Bavarian princess (among other titles that she bore) that concerned itself with outfitting nubile girls. As well, he represented a fire insurance company and kept the municipality’s poor budget. Schmidt faced penalties for having set his dog on a few boys from Sankt Julian who earlier had wanted to tease the dog. Schmidt was transferred in 1898 to Dierbach. His successor was Jakob Müller, who was now also in the service of the church, and in 1903, he was transferred to Schrollbach. There was more quick turnover. Teachers came one after the other: Michael Assenbaum, Johannes Göhring, Karl Linn. Reinhard Blauth from Weilerbach appeared during the First World War, and not surprisingly he was soon called into the military. Alwine Leppla and Ernst Neumann took over for him while he was fighting. Blauth came back from wartime imprisonment in 1920. He taught in Eschenau until 1926 and then had himself transferred to Weilerbach, where he distinguished himself as a local history writer. The Eschenau school was dissolved in 1969. The last local schoolteacher was Volker Jung from Altenkirchen, who died young, but not before working as the acting headteacher at the Realschule Schönenberg-Kübelberg. Eschenau’s primary school pupils nowadays attend classes in Sankt Julian, while the Hauptschule for the village is the one in Lauterecken. Gymnasien can be attended in Kusel and Lauterecken.[72]

Gumbsweiler