Nuclear membrane

| Nuclear membrane | |

|---|---|

|

Human cell nucleus | |

| Identifiers | |

| TH | H1.00.01.2.01001 |

| FMA | 63888 |

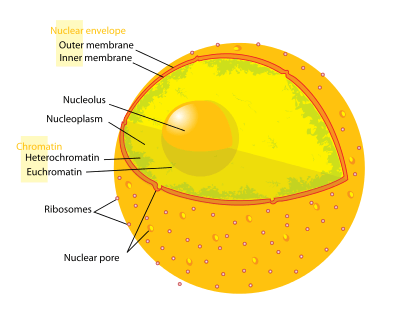

A nuclear membrane, also known as the [1] nucleolemma[2] or karyotheca,[3] is the phospho lipid bilayer membrane which surrounds the genetic material and nucleolus in eukaryotic cells.

The nuclear membrane consists of two lipid bilayers—the inner nuclear membrane, and the outer nuclear membrane. The space between the membranes is called the perinuclear space, a region contiguous with the lumen (inside) of the endoplasmic reticulum. It is usually about 20–40 nm wide.[4][5] The nuclear membrane also has many small holes called nuclear pores that allow material to move in and out of the nucleus. It should not be confused with nuclear envelope , which consists of 2 nuclear membranes (the outer and inner membranes) as well as the inter membrane space and associated structures.

Outer membrane

The outer nuclear membrane also shares a common border with endoplasmic reticulum.[6] While it is physically linked, the outer nuclear membrane contains proteins found in far higher concentrations than the endoplasmic reticulum.[7] All 4 Nesprin proteins present in mammals are expressed in the outer nuclear membrane.[8] Nesprin proteins connect cytoskeletal filaments to the nucleoskeleton.[9] Nesprin-mediated connections to the cytoskeleton contribute to nuclear positioning and to the cell’s mechanosensory function.[10] KASH-domain proteins of Nesprin-1 and -2 are part of a LINC complex (Linker of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton) and can bind directly to cystoskeletal components, such as actin filaments, or can bind to proteins in the luminal domain of the nuclear membrane.[11] Nesprin-3 and-4 may play a role in unloading enormous cargo; Nesprin-3 proteins bind plectin and link the nuclear envelope to cytoplasmic intermediate filaments.[12] Nesprin-4 proteins bind the plus end directed motor kinesin-1.[13] The outer nuclear membrane is also involved in development, as it fuses with the inner nuclear membrane to form nuclear pores.[14]

Inner membrane

The inner nuclear membrane encloses the nucleoplasm, and is covered by the nuclear lamina, a mesh of intermediate filaments which stabilizes the nuclear membrane as well as being involved in chromatin function and entire expression.[7] It is connected to the outer membrane by nuclear pores which penetrate the membranes. While the two membranes and the endoplasmic reticulum are linked, proteins embedded in the membranes tend to stay put rather than dispersing across the continuum.[15]

Nuclear pores

The nuclear membrane is punctured by thousands of nuclear pore complexes—large hollow proteins about 100 nm across, with an inner channel about 40 nm wide.[7] They link the inner and outer nuclear membranes.

Cell division

During the G2 phase of interphase, the nuclear membrane increases its surface area and doubles its number of nuclear pore complexes.[7] In lower eukaryotes, such as yeast, which undergo closed mitosis, the nuclear membrane stays intact during cell division. The spindle fibers either form within the membrane, or penetrate it without tearing it apart.[7] In higher eukaryotes (animals as well as plants), the nuclear membrane must break down during the prometaphase state of mitosis to allow the mitotic spindle fibers to access the chromosomes inside. The breakdown and reformation processes are not well understood.

Breakdown

In mammals, the nuclear membrane can break down within minutes, following a set of steps during the early stages of Mitosis. First, M-Cdk's phosphorylate nucleoporin polypeptides and they are selectively removed from the nuclear pore complexes. After that, the rest of the nuclear pore complexes break apart simultaneously. Biochemical evidence suggests that the nuclear pore complexes disassemble into stable pieces rather than disintegrating into small polypeptide fragments.[7] M-Cdk's also phosphorylate elements of the nuclear lamina (the framework that supports the envelope) leading to the dis-assembly of the lamina and hence the envelope membranes into small vesicles.[16] Electron and fluorescence microscopy has given strong evidence that the nuclear membrane is absorbed by the endoplasmic reticulum—nuclear proteins not normally found in the endoplasmic reticulum show up during mitosis.[7]

Reformation

Exactly how the nuclear membrane reforms during telophase of mitosis is debated. Two theories exist[7]—

- Vesicle fusion—where vesicles of nuclear membrane fuse together to rebuild the nuclear membrane

- Reshaping of the endoplasmic reticulum—where the parts of the endoplasmic reticulum containing the absorbed nuclear membrane envelop the nuclear space, reforming a closed membrane.

References

- ↑ Georgia State University. "Cell Nucleus and Nuclear Envelope". gsu.edu.

- ↑ "Nuclear membrane". Biology Dictionary. Biology Online. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ "nuclear membrane". Merriam Webster. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ "Perinuclear space". Dictionary. Biology Online. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ Berrios, Miguel, ed. (1998). Nuclear structure and function. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780125641555.

- ↑ "Chloride channels in the Nuclear membrane" (PDF). Harvard.edu. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hetzer, Mertin (February 3, 2010). "The Nuclear Envelope". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (3): a000539. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000539. PMC 2829960

. PMID 20300205.

. PMID 20300205. - ↑ Wilson, Katherine L.; Berk, Jason M. (2010-06-15). "The nuclear envelope at a glance". J Cell Sci. 123 (12): 1973–1978. doi:10.1242/jcs.019042. ISSN 0021-9533. PMC 2880010

. PMID 20519579.

. PMID 20519579. - ↑ Burke, Brian; Roux, Kyle J. (2009-11-01). "Nuclei take a position: managing nuclear location". Developmental Cell. 17 (5): 587–597. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.018. ISSN 1878-1551. PMID 19922864.

- ↑ Uzer, Gunes; Thompson, William R.; Sen, Buer; Xie, Zhihui; Yen, Sherwin S.; Miller, Sean; Bas, Guniz; Styner, Maya; Rubin, Clinton T. (2015-06-01). "Cell Mechanosensitivity to Extremely Low-Magnitude Signals Is Enabled by a LINCed Nucleus". STEM CELLS. 33 (6): 2063–2076. doi:10.1002/stem.2004. ISSN 1066-5099. PMC 4458857

. PMID 25787126.

. PMID 25787126. - ↑ Crisp, Melissa; Liu, Qian; Roux, Kyle; Rattner, J. B.; Shanahan, Catherine; Burke, Brian; Stahl, Phillip D.; Hodzic, Didier (2006-01-02). "Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex". The Journal of Cell Biology. 172 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1083/jcb.200509124. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2063530

. PMID 16380439.

. PMID 16380439. - ↑ Wilhelmsen, Kevin; Litjens, Sandy H. M.; Kuikman, Ingrid; Tshimbalanga, Ntambua; Janssen, Hans; van den Bout, Iman; Raymond, Karine; Sonnenberg, Arnoud (2005-12-05). "Nesprin-3, a novel outer nuclear membrane protein, associates with the cytoskeletal linker protein plectin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 171 (5): 799–810. doi:10.1083/jcb.200506083. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2171291

. PMID 16330710.

. PMID 16330710. - ↑ Roux, Kyle J.; Crisp, Melissa L.; Liu, Qian; Kim, Daein; Kozlov, Serguei; Stewart, Colin L.; Burke, Brian (2009-02-17). "Nesprin 4 is an outer nuclear membrane protein that can induce kinesin-mediated cell polarization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (7): 2194–2199. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808602106. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2650131

. PMID 19164528.

. PMID 19164528. - ↑ Fichtman, Boris; Ramos, Corinne; Rasala, Beth; Harel, Amnon; Forbes, Douglass J. (2010-12-01). "Inner/Outer Nuclear Membrane Fusion in Nuclear Pore Assembly". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 21 (23): 4197–4211. doi:10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0309. ISSN 1059-1524. PMC 2993748

. PMID 20926687.

. PMID 20926687. - ↑ "The inner nuclear membrane: simple, or very complex?". The EMBO Journal. 20 (12): 2989–2994. April 19, 2001. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.12.2989. PMC 150211

. PMID 11406575. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

. PMID 11406575. Retrieved 7 December 2012. - ↑ Alberts (et al) (2008). "Chapter 17: The Cell Cycle". Molecular Biology of The Cell (5th ed.). New York: Garland Science. pp. 1079–1080. ISBN 978-0-8153-4106-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuclear membranes. |

- Histology image: 20102loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Animations of nuclear pores and transport through the nuclear envelope

- Illustrations of nuclear pores and transport through the nuclear membrane

- Nuclear membrane at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)