Jordan

| The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan المملكة الأردنية الهاشمية Al-Mamlakah Al-Urdunnīyah Al-Hāshimīyah |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "God, Country, King" الله، الوطن، الملك (Arabic) Allah, Al-Waṭan, Al-Malik[1] |

||||||

| Anthem: (English: The Royal Anthem of Jordan) السلام الملكي الأردني Al-Salam Al-Malaki Al-Urdunni |

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

_-_JOR_-_UNOCHA.svg.png) Map of Jordan showing influential governorate centers

|

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Amman 31°57′N 35°56′E / 31.950°N 35.933°E | |||||

| Official languages | Arabic | |||||

| Ethnic groups |

|

|||||

| Demonym | Jordanian | |||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | |||||

| • | King | Abdullah II | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Hani Al-Mulki | ||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||

| • | Lower house | House of Representatives | ||||

| Independence from Britain | ||||||

| • | The Emirate of Transjordan | 11 April 1921 | ||||

| • | The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan | 25 May 1946 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 89,341 km2 (112th) 35,637 sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | November 2016 estimate | 9,852,371[2] | ||||

| • | November 2015 census | 9,531,712 | ||||

| • | Density | 107/km2 (100th) 276/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $82.991 billion[3] (87th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $12,162[3] (86th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $38.210 billion[3] (92nd) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $5,599[3] (95th) | ||||

| Gini (2011) | 35.4[4] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | high · 80th |

|||||

| Currency | Dinar (JOD) | |||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +962 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | JO | |||||

| Internet TLD | .jo .الاردن |

|||||

Jordan (/ˈdʒɔːrdən/; Arabic: الأردن Al-Urdunn), officially The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (Arabic: المملكة الأردنية الهاشمية Al-Mamlakah Al-Urdunnīyah Al-Hāshimīyah), is an Arab kingdom in Western Asia, on the East Bank of the Jordan River. Jordan is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the east and south, Iraq to the north-east, Syria to the north, Israel, Palestine and the Dead Sea to the west and the Red Sea in its extreme south-west.[6] Jordan is strategically located at the crossroads of Asia, Africa and Europe.[7] The capital, Amman, is Jordan's most populous city as well as the country's economic, political and cultural centre.[8]

What is now Jordan has been inhabited by humans since the Paleolithic period. Three stable kingdoms emerged there at the end of the Bronze Age: Ammon, Moab and Edom. Later rulers include the Nabataean Kingdom, the Roman Empire, and the Ottoman Empire.[9] After the Great Arab Revolt against the Ottomans in 1916 during World War I, the Ottoman Empire was partitioned by Britain and France. The Emirate of Transjordan was established in 1921 by the then Emir Abdullah I and became a British protectorate. In 1946, Jordan became an independent state officially known as The Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan. Jordan captured the West Bank during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and the name of the state was changed to The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in 1949.[10] Jordan is a founding member of the Arab League and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, and is one of two Arab states to have signed a peace treaty with Israel. The country is a constitutional monarchy, but the king holds wide executive and legislative powers.[11]

Jordan is a relatively small semi-arid almost landlocked country with a population numbering at 9.5 million. Sunni Islam, practiced by around 92% of the population, is the dominant religion in Jordan. It coexists with an indigenous Christian minority. Jordan is considered to be among the safest of Arab countries in the Middle East, and has avoided long-term terrorism and instability.[12] In the midst of surrounding turmoil, it has been greatly hospitable, accepting refugees from almost all surrounding conflicts as early as 1948, with most notably the estimated 2.1 million Palestinians and the 1.4 million Syrian refugees residing in the country.[13] The kingdom is also a refuge to thousands of Iraqi Christians fleeing the Islamic State.[14] While Jordan continues to accept refugees, the recent large influx from Syria placed substantial strain on national resources and infrastructure.[15]

Jordan is classified as a country of "high human development" with an "upper middle income" economy. The Jordanian economy, one of the smallest economies in the region, is attractive to foreign investors based upon a skilled workforce.[16] The country is a major tourist destination, and also attracts medical tourism due to its well developed health sector.[17] Nonetheless, a lack of natural resources, large flow of refugees and regional turmoil have crippled economic growth.[18]

Etymology

Jordan is named after the Jordan River, where Jesus is said to have been baptized. The origin of the river's name is debated, but the most common explanation is that it derives from the word "yarad" (the descender, "Yarden" is the Hebrew name for the river), found in Hebrew, Aramaic, and other Semitic languages. Others regard the name as having an Indo-Aryan origin, combining the words "yor" (year) and "don" (river), reflecting the river's perennial nature. Another theory is that it is from the Arabic root word "wrd" (to come to), as in people coming to a major source of water.[19]

The name Jordan appears in an ancient Egyptian papyrus called Papyrus Anastasi I, dating back to around 1000 BC.[20] The lands of modern-day Jordan were historically called "Transjordan", meaning "beyond the Jordan River". The name was Arabized into "Al-Urdunn" during the Muslim conquest of the Levant. During crusader rule, it was called "Oultrejordain". In 1921, the Emirate of Transjordan was established and after it gained its independence in 1946, it became "The Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan". The name was changed in 1949 into "The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan". "Hashemite" is the house name of the royal family.[21]

History

Ancient period

Jordan is rich in Paleolithic remains, holding evidence of inhabitance by Homo erectus, Neanderthal and modern humans.[22] The oldest evidence of human habitation dates back around 250,000 years.[23] The Kharanah area in eastern Jordan has evidence of human huts from about 20,000 years ago.[24] Other Paleolithic sites include Pella and Al-Azraq.[25] In the Neolithic period, several settlements began to develop, most notably an agricultural community called 'Ain Ghazal in what is now Amman,[26] one of the largest known prehistoric settlements in the Near East.[27] Plaster statues estimated to date back to around 7250 BC were uncovered there, and are among the oldest large human statues ever found.[28][29] Villages of Bab edh-Dhra in the Dead Sea area, Tal Hujayrat Al-Ghuzlan in Aqaba and Tulaylet Ghassul in the Jordan Valley all date to the Chalcolithic period.[30]

The prehistoric period of Jordan ended at around 2000 BC when the Semitic nomads known as the Amorites entered the region. During the Bronze Age and Iron Age, present-day Jordan was home to several ancient kingdoms, whose populations spoke Semitic languages of the Canaanite group.[31] Among them were Ammon, Edom and Moab, which are described as tribal kingdoms rather than states. They are mentioned in ancient texts such as the Old Testament. Archaeology finds have shown that Ammon was in the area of the modern city of Amman, Moab controlled the highlands east of the Dead Sea and Edom controlled the area around Wadi Araba.[32]

These Transjordanian kingdoms were in continuous conflict with the neighboring Hebrew kingdoms of Israel and Judah, centered west of the Jordan River, though Israel was known to have at times controlled small parts east of the River.[34] Frequent confrontations ensued and tensions between them increased. One record of this is the Mesha Stele erected by the Moabite king Mesha around 840 BC on which he lauds himself for the building projects that he initiated in Moab and commemorates his glory and victory against the Israelites.[35] The stele constitutes one of the most important direct accounts of Biblical history.[33] Subsequently, the Assyrian Empire reduced these kingdoms to vassals. When the region was later under the influence of the Babylonians, the Old Testament mentions that these kingdoms aided them in the 597 BC sack of Jerusalem.[36]

These kingdoms are believed to have existed throughout fluctuations in regional rule and influence. They passed through the control of several distant empires, including the Akkadian Empire (2335–2193 BC), Ancient Egypt (1500–1300 BC), the Hittite Empire (1400–1300 BC), the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC), the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC), the Neo-Babylonian Empire (604–539 BC), the Achaemenid Empire (539–332 BC) and the Hellenistic Empire of Macedonia.[9] However, by the time of Roman rule in the Levant around 63 BC, the people of Ammon, Edom and Moab had lost their distinct identities, and were assimilated into Roman culture.[32]

Classical period

Alexander the Great's conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in 332 BC introduced Hellenistic culture to the Middle East. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, his empire split among his generals and in the end, much of the land of modern-day Jordan was disputed between the Ptolemies based in Egypt and the Seleucids based in Syria.[37] In the south and east, the Nabataeans had an independent kingdom.[37] Campaigns by different Greek generals aspiring to annex the Nabataean Kingdom were unsuccessful.[38]

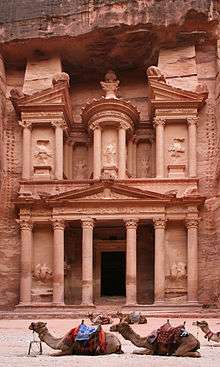

The Nabataeans were nomadic Arabs who derived wealth from their capital Petra, whose proximity to major trade routes led to it becoming a regional hub.[38] The Ptolemies were eventually displaced from the region by the Seleucid Empire. The conflict between these two groups enabled the Nabataeans to extend their kingdom northwards well beyond Petra in Edom.[37] The Nabataeans are known for their great ability in constructing efficient water collecting methods in the barren deserts and their talent for carving structures such as the Al-Khazneh temple into solid rocks.[38] These nomads spoke Arabic and wrote in Nabataean alphabets, which were developed from Aramaic script during the 2nd century BC, and are regarded by scholars to have evolved into the Arabic alphabet around the 4th century AD.[39]

The Greeks founded new cities in Jordan including Philadelphia (Amman), Gerasa (Jerash), Gedara (Umm Qays), Pella (Tabaqat Fahl) and Arbila (Irbid). Later, under Roman rule, these joined other Hellenistic cities in Palestine and Syria to form the Decapolis League, a loose confederation linked by economic and cultural interests: Scythopolis, Hippos, Capitolias, Canatha and Damascus were among its members.[40] The most notable Hellenistic site in Jordan is at Iraq Al-Amir, just west of modern-day Amman.[9]

Roman legions under Pompey conquered much of the Levant in 63 BC, inaugurating a period of Roman rule that lasted for centuries.[9] In 106 AD, Emperor Trajan annexed the nearby Nabataean Kingdom without any opposition, and rebuilt the King's Highway which became known as the Via Traiana Nova road.[41] During Roman rule the Nabataeans continued to flourish and replaced their local gods with Christianity.[42] Roman remains include, in Amman, the Temple of Hercules at the Amman Citadel and the Roman theater. Jerash contains a well-preserved Roman city that had 15,000 inhabitants at its height.[43] Jerash was visited by Emperor Hadrian during his journey to Palestine.[42] In 324 AD, the Roman Empire split, and the Eastern Roman Empire (later known as the Byzantine Empire) continued to control or influence the region until 636 AD. Christianity had become legal within the empire in 313 AD and the official state religion in 390 AD, after Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity.[42]

Ayla city (modern day Aqaba) in southern Jordan also came under Byzantine Empire rule. The Aqaba Church was built around 300 AD, and is considered the world's first purpose built Christian church.[44] The Byzantines built 16 churches just south of Amman in Umm ar-Rasas.[45] Administratively the area of Jordan fell under the Diocese of the East, and was divided between the provinces of Palaestina Secunda in the north-west and Arabia Petraea in the south and east. Palaestina Salutaris in the south was split off from Arabia Petraea in the late 4th century.[46] The Sassanian Empire in the east became the Byzantines' rivals, and frequent confrontations sometimes led to the Sassanids controlling some parts of the region, including Transjordan.[47]

Islamic era

Muslims from what is now Saudi Arabia invaded the region from the south.[42] The Arab Christian Ghassanids, clients of the Byzantines, were defeated despite imperial support.[48] While the Muslim forces lost to the Byzantines in their first direct engagement during the Battle of Mu'tah in 629, in what is now the Karak Governorate, the Byzantines lost control of the Levant when they were defeated by the Rashidun army in 636 at the Battle of Yarmouk just north of modern-day Jordan. The region was Arabized, and the Arabic language became widespread.[42]

Transjordan was an essential territory for the conquest of nearby Damascus.[49] The first, or Rashidun, caliphate was followed by that of the Ummayad (661–750). Under Umayyads rule, several desert castles were constructed, such as Qasr Al-Mshatta, Qasr Al-Hallabat, Qasr Al-Kharanah, Qasr Tuba, Qasr Amra, and a large administrative palace in Amman.[50] The Abbasid campaign to take over the Umayyad empire began in the region of Transjordan. After the decline of the Abbasid Caliphate, the area was ruled by the Fatimids, then by the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (1115–1189).[49]

The Crusaders constructed about nine Crusader castles as part of the lordship of Oultrejordain, including those of Montreal, Al-Karak and Wu'ayra (in Petra).[50] In the 12th century, the Crusaders were defeated by Saladin, the founder of the Ayyubids dynasty (1189–1260). The Ayyubids built a new castle at Ajloun and rebuilt the former Roman fort of Qasr Azraq. Several of these castles were used and expanded by the Mamluks (1260–1516), who divided Jordan between the provinces of Karak and Damascus. During the next century Transjordan experienced Mongol attacks, but the Mongols were ultimately repelled by the Mamluks after the Battle of Ain Jalut (1260).[50]

In 1516, Ottoman forces conquered Mamluk territory.[51] Agricultural villages in Jordan witnessed a period of relative prosperity in the 16th century, but were later abandoned.[52] For the next centuries, Ottoman rule in the region, at times, was virtually absent and reduced to annual tax collection visits.[52] This led to a short-lived occupation by the Wahhabi forces (1803–1812), an ultraorthodox Islamic movement that emerged in Najd in modern-day Saudi Arabia.[37] Ibrahim Pasha, son of the governor of the Egypt Eyalet under the request of the Ottoman sultan, rooted out the Wahhabis between 1811 and 1818.[37] In 1833 Ibrahim Pasha turned on the Ottomans and established his rule over the Levant. His oppressive policies led to the unsuccessful peasants' revolt in Palestine in 1834.[53] The cities of Al-Salt and Al-Karak were destroyed by Ibrahim Pasha's forces for harboring a peasants' revolt leader. Egyptian rule was later forcibly ended, with Ottoman rule restored.[53]

Russian persecution of Sunni Muslim Circassians and Chechens led to their immigration into the region in 1867, where today they form a small part of the country's ethnic fabric.[54] Overall population however declined due to oppression and neglect.[55] Urban settlements with small populations included: Al-Salt, Irbid, Jerash and Al-Karak.[56] The under-development of urban life in Jordan was exacerbated by the settlements being sometimes raided by Bedouins.[23] Ottoman oppression provoked the region's both non-Bedouin and Bedouin tribes to revolt, Bedouin tribes like; Adwan, Bani Hassan, Bani Sakhr and the Howeitat. The most notable revolts were the Shoubak Revolt (1905) and the Karak Revolt (1910), which were brutally suppressed.[54] Jordan's location lies on a pilgrimage route taken by Muslims going to Mecca, which helped the population economically when the Ottomans constructed the Hejaz Railway linking Mecca with Istanbul in 1908. Before the construction of the railway, the Ottomans built fortresses along the Hajj route to secure pilgrims' caravans.[57]

Modern era

Four centuries of stagnation during Ottoman rule ended during World War I when the Arab Revolt occurred in 1916, driven by long-term Arab resentment towards the Ottoman authorities[55] and the emergence of Arab nationalism.[58] The revolt was launched by the Hashemite clan of Hejaz, who claim descent from the Islamic prophet Muhammad, led by Sharif Hussein of Mecca.[59] The conquest of Transjordan garnered the support of the local Bedouin tribes, Circassians and Christians.[60] The revolt was supported by the Allies of World War I including Britain and France.[61]

The Great Arab Revolt successfully gained control of most of territories of the Hejaz and the Levant, including the region east of the Jordan River. However, it failed to gain international recognition as an independent state, due mainly to the secret Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916 and the Balfour Declaration of 1917. This was seen by the Hashemites and the Arabs as a betrayal of their previous agreements with the British, including the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence of 1915, in which the British stated their willingness to recognize the independence of a unified Arab state stretching from Aleppo to Aden under the rule of the Hashemites. The region was divided and Abdullah I, the second son of Sharif Hussein arrived from Hejaz by train in Ma'an in southern Jordan, where he was greeted by Transjordanian leaders.[37] Abdullah established the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921, which then became a British protectorate.[62]

The first organized army in Jordan was established on 22 October 1920, and was named the "Arab Legion". The Legion grew from 150 men in 1920 to 8,000 in 1946.[63] Multiple difficulties emerged upon the assumption of power in the region by the Hashemite leadership. In Transjordan, small local rebellions at Kura in 1921 and 1923 were suppressed by Emir Abdullah with the help of British forces.[37] Wahhabis from Najd regained strength and repeatedly raided the southern parts of his territory in (1922–1924), seriously threatening the Emir's position.[37] The Emir was unable to repel those raids without the aid of the local Bedouin tribes and the British, who maintained a military base with a small RAF detachment close to Amman.[37]

In September 1922, the Council of the League of Nations recognized Transjordan as a state under the British Mandate for Palestine and the Transjordan memorandum, and excluded the territories east of the Jordan River from the provisions of the mandate dealing with Jewish settlement.[64] Transjordan remained a British mandate until 1946.[65]

Post-independence

The Treaty of London, signed by the British Government and the Emir of Transjordan on 22 March 1946, recognised the independence of Transjordan upon ratification by both countries parliaments.[66] On 25 May 1946 the Emirate of Transjordan became "The Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan", as the ruling Emir was re-designated as "King" by the parliament of Transjordan on the day it ratified the Treaty of London.[67] The name was changed to "The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan" in 1949. Jordan became a member of the United Nations on 14 December 1955.[10]

On 15 May 1948, as part of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Jordan invaded Palestine together with other Arab states.[68] Following the war, Jordan occupied the West Bank and on 24 April 1950 Jordan formally annexed these territories. In response, some Arab countries demanded Jordan's expulsion from the Arab League.[69] On 12 June 1950, the Arab League declared the annexation was a temporary, practical measure and that Jordan was holding the territory as a "trustee" pending a future settlement.[70]

King Abdullah was assassinated at the Al-Aqsa Mosque in 1951 by a Palestinian militant, amid rumors he intended to sign a peace treaty with Israel. Abdullah was succeeded by his son Talal, however Talal soon abdicated due to illness in favor of his eldest son Hussein, who ascended the throne in 1953.[71] On 1 March 1956, King Hussein dismissed a number of British personnel serving in the Jordanian Army, an act of Arabization made to ensure the complete sovereignty of Jordan.[72] Neighboring Iraq was also ruled by a Hashemite monarchy; Faisal II of Iraq, who was Hussein's cousin. 1958 witnessed the emergence of the Arab Federation between the two kingdoms, as a response to the formation of the United Arab Republic between Egypt and Syria. The union lasted only six months, being dissolved after Faisal II was deposed by a military coup.[73]

Jordan signed a military pact with Egypt just before Israel launched a preemptive strike on Egypt to begin the Six-Day War in June 1967, where Jordan and Syria joined the war. It ended in an Arab defeat and the West Bank came under Israeli control. Jordan also fought in the War of Attrition, which included the 1968 Battle of Karameh where the combined forces of the Jordanian Armed Forces and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) repelled an Israeli attack on the Karameh camp on the Jordanian border with the West Bank.[74] Despite the fact that the Palestinians had limited involvement against the Israeli forces, the events at Karameh gained wide recognition and acclaim in the Arab world. As a result, the time period following the battle witnessed an upsurge of support for Palestinian paramilitary elements (the fedayeen) within Jordan from other Arab countries, the fedayeen soon became a threat to Jordan's rule of law. In September 1970, the Jordanian army targeted the fedayeen and the resultant fighting led to the expulsion of Palestinian fighters from various PLO groups into Lebanon, in a civil war that became known as Black September.[75]

During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Arab league forces waged a war on Israel and fighting occurred along the 1967 Jordan River cease-fire line. Jordan sent a brigade to Syria to attack Israeli units on Syrian territory but did not engage Israeli forces from Jordanian territory. At the Rabat summit conference in 1974, Jordan agreed, along with the rest of the Arab League, that the PLO was the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people". Subsequently, Jordan renounced its claims to the West Bank in 1988.[75]

At the 1991 Madrid Conference, Jordan agreed to negotiate a peace treaty sponsored by the US and the Soviet Union. The Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace was signed on 26 October 1994.[75] In 1997, Israeli agents allegedly entered Jordan using Canadian passports and poisoned Khaled Meshal, a senior Hamas leader. Israel provided an antidote to the poison and released dozens of political prisoners, including Sheikh Ahmed Yassin after King Hussein threatened to annul the peace treaty.[75]

On 7 February 1999, Abdullah II ascended the throne upon the death of his father Hussein.[76] Jordan's economy has improved since then. Abdullah II has been credited with increasing foreign investment, improving public-private partnerships and providing the foundation for Aqaba's free-trade zone and Jordan's flourishing information and communication technology (ICT) sector. He also set up five other special economic zones. As a result of these reforms, Jordan's economic growth has doubled to 6% annually compared to the latter half of the 1990s.[77] However, the Great Recession and regional turmoil in the 2010s severely crippled the Jordanian economy and its growth, making it increasingly reliant on foreign aid.[78]

Al-Qaeda under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's leadership launched coordinated explosions in three hotel lobbies in Amman on 9 November 2005, resulting in 60 deaths and 115 injured. The bombings, which targeted civilians, caused widespread outrage among Jordanians.[79] The attack is considered to be a rare event in the country, and Jordan's internal security was dramatically improved afterwards. No major terrorist attacks have occurred since then.[80]

The Arab Spring began sweeping the Arab world in 2011, where large scale protests erupted demanding economic and political reforms. However, many of these protests in some countries turned into civil wars and more instability. In Jordan, in response to domestic unrest, Abdullah II replaced his prime minister and introduced a number of reforms including; amending the Constitution and establishing a number of governmental commissions.[81] The King told the new prime minister to "take quick, concrete and practical steps to launch a genuine political reform process, to strengthen democracy and provide Jordanians with the dignified life they deserve".[82]

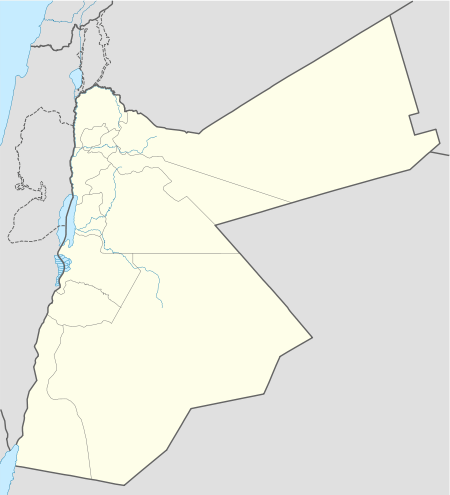

Geography

Jordan sits strategically at the crossroads of the continents of Asia, Africa and Europe,[7] in the Levant area of the Fertile Crescent, a cradle of civilization.[83] It is 89,341 square kilometres (34,495 sq mi) large, and 400 kilometres (250 mi) long between its northernmost and southernmost points; Umm Qais and Aqaba respectively.[84] The kingdom lies between 29° and 34° N, and 34° and 40° E. The east is an arid plateau irrigated by oases and seasonal water streams.[84] Major cities are overwhelmingly located on the north-western part of the kingdom due to its fertile soils and relatively abundant rainfall. These include Irbid, Jerash and Zarqa in the northwest, the capital Amman and Al-Salt in the central west, and Madaba, Al-Karak and Aqaba in the southwest.[85] Major towns in the eastern part of the country are the oasis towns of Azraq and Ruwaished.[83]

In the west a highland area of arable land and Mediterranean evergreen forestry drops suddenly into the Jordan Rift Valley. The rift valley contains the Jordan River and the Dead Sea, which separates Jordan from Israel and the Palestinian Territories. Jordan has a 26 kilometres (16 mi) shoreline on the Gulf of Aqaba in the Red Sea, but is otherwise landlocked.[6] The Yarmouk River, an eastern tributary of the Jordan, forms part of the boundary between Jordan and Syria (including the occupied Golan Heights) to the north. The other boundaries are formed by several international and local agreements and do not follow well-defined natural features. The highest point is Jabal Umm al Dami, at 1,854 m (6,083 ft) above sea level, while the lowest is the Dead Sea −420 m (−1,378 ft), the lowest land point on earth.[83]

Jordan has a diverse range of habitats, ecosystems and biota due, to its varied landscapes and environments.[86] The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature was set up in 1966 to protect and manage Jordan's natural resources. Nature reserves in Jordan include the Dana Biosphere Reserve, the Azraq Wetland Reserve, the Shaumari Wildlife Reserve and the Mujib Nature Reserve.[87]

Over two thousand plant species have been recorded in Jordan.[88] Many of the flowering plants bloom in the spring after the winter rains and the type of vegetation depends largely on the levels of precipitation. The mountainous regions in the northwest are clothed in forests, while further south and east the vegetation becomes more scrubby and transitions to steppe-type vegetation.[89] Forests cover 1.5 million dunums (1,500 km2), less than 2% of Jordan, making Jordan among the world's least forested countries, the internationally average being 15%.[90]

Climate

The climate in Jordan varies greatly. Generally, the further inland from the Mediterranean, greater contrasts in temperature occur and the less rainfall there is. The country's average elevation is 812 m (2,664 ft) (SL).[84] The highlands above the Jordan Valley, mountains of the Dead Sea and Wadi Araba and as far south as Ras Al-Naqab are dominated by a Mediterranean climate, while the eastern and northeastern areas of the country are arid desert.[91] Although the desert parts of the kingdom reach high temperatures, the heat is usually moderated by low humidity and a daytime breeze, while the nights are cool.[92]

Summers, lasting from May to September, are hot and dry, with temperatures averaging around 32 °C (90 °F) and sometimes exceeding 40 °C (104 °F) between July and August.[92] The winter, lasting from November to March, is relatively cool, with temperatures averaging around 13 °C (55 °F). Winter also sees frequent showers and occasional snowfall in some western elevated areas.[91]

Politics and government

Jordan is a constitutional monarchy, but the King holds wide executive and legislative powers. He serves as Head of State and Commander-in-Chief and appoints the prime minister and heads of security directorates. The prime minister is free to choose his own cabinet and regional governors.[11] However, the king may dissolve parliament and dismiss the government.[93] The capital city of Jordan is Amman, located in north-central Jordan.[8]

Jordan is divided into 12 governorates (muhafazah) (informally grouped into three regions: northern, central, southern). These are subdivided into a total of 52 nawahi, which are further divided into neighborhoods in urban areas or into towns in rural ones.[94] The Parliament of Jordan consists of two chambers: the upper Senate (Arabic: مجلس الأعيان Majlis Al-'Aayan) and the lower House of Representatives (Arabic: مجلس النواب Majlis Al-Nuwab). All 65 members of the Senate are directly appointed by the King, they are usually veteran politicians or are known to have held previous positions in the House of Representatives or in the government.[95] The 130 members of the House of Representatives are elected through proportional representation in 23 constituencies on nationwide party lists for a 4-year election cycle.[96] Minimum quotas exist in the House of Representatives for women (15 seats, though they won 20 seats in the 2016 election), Christians (9 seats) and Circassians and Chechens (3 seats).[97] Three constituencies are allocated for the Bedouins of the northern, central and southern Badias.[98]

Jordan has around 50 political parties representing nationalist, Islamist, leftist and liberal ideologies.[99] Political parties contested a fifth of the seats in the 2016 elections, the remainder belonging to independent politicians.[100] The government can be dismissed by a two-thirds vote of "no confidence" by the House of Representatives. Political parties come under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Interior, and may not be established on the basis of religion.[101]

The Constitution of Jordan was adopted in 1952 and has been amended a number of times, most recently in 2016.[102] Article 97 of Jordan's constitution guarantees the independence of the judicial branch, stating that judges are "subject to no authority but that of the law." Article 99 divides the courts into three categories: civil, religious, and special. The civil courts deal with civil and criminal matters, and have jurisdiction over all persons in all matters civil and criminal, including cases brought against the government. The civil courts include Magistrate Courts, Courts of First Instance, Courts of Appeal,[103] High Administrative Courts which hear cases relating to administrative matters,[104] and the Constitutional Court which was set up in 2012 in order to hear cases regarding the constitutionality of laws.[105] The religious court system's jurisdiction extends to matters of personal status such as divorce and inheritance, and is partially based on Sharia Islamic law.[106] The special court deals with cases forwarded by the civil one.[107]

The current monarch, Abdullah II, ascended the throne in February 1999 after the death of his father Hussein. Abdullah reaffirmed Jordan's commitment to the peace treaty with Israel and its relations with the United States. He refocused the government's agenda on economic reform, during his first year. King Abdullah's eldest son, Prince Hussein is the current Crown Prince of Jordan.[108] The current prime minister is Hani Al-Mulki who received his position on 29 May 2016.[109]

The 2010 Arab Democracy Index from the Arab Reform Initiative ranked Jordan first in the state of democratic reforms out of fifteen Arab countries.[110] Jordan ranked first among the Arab states and 78th globally in the Human Freedom Index in 2015,[111] and ranked 55th out of 175 countries in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) issued by Transparency International in 2014, where 175th is most corrupt.[112] In the 2016 Press Freedom Index maintained by Reporters Without Borders, Jordan ranked 135th out of 180 countries worldwide, and 5th of 19 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region. Jordan's score was 44 on a scale from 0 (most free) to 105 (least free). The report added "the Arab Spring and the Syrian conflict have led the authorities to tighten their grip on the media and, in particular, the Internet, despite an outcry from civil society".[113] Jordanian media consists of public and private institutions. Popular Jordanian newspapers include: Ammon News, Ad-Dustour and Jordan Times. The most two watched local TV stations are Ro'ya TV and Jordan TV.[114] Internet penetration in Jordan reached 76% in 2015.[115]

Administrative divisions

| Map | Governorate | Capital | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Northern region | ||||

| 1 | Irbid | Irbid | 1,770,158 | ||

| 2 | Ajloun | Ajloun | 176,080 | ||

| 3 | Jerash | Jerash | 237,059 | ||

| 4 | Mafraq | Mafraq | 549,948 | ||

| Central region | |||||

| 5 | Balqa | Al-Salt | 491,709 | ||

| 6 | Madaba | Madaba | 189,192 | ||

| 7 | Amman | Amman | 4,007,256 | ||

| 8 | Zarqa | Zarqa | 1,364,878 | ||

| Southern region | |||||

| 9 | Karak | Al-Karak | 316,629 | ||

| 10 | Tafila | Tafila | 96,291 | ||

| 11 | Ma'an | Ma'an | 144,083 | ||

| 12 | Aqaba | Aqaba | 188,160 | ||

Foreign relations

The kingdom has followed a pro-Western foreign policy and maintained close relations with the United States and the United Kingdom. During the first Gulf War (1990), these relations were damaged by Jordan's neutrality and its maintenance of relations with Iraq. Later, Jordan restored its relations with Western countries through its participation in the enforcement of UN sanctions against Iraq and in the Southwest Asia peace process. After King Hussein's death in 1999, relations between Jordan and the Persian Gulf countries greatly improved.[116]

Jordan is a key ally of the USA and UK and, together with Egypt, is one of only two Arab nations to have signed peace treaties with Israel, Jordan's direct neighbour.[117] Jordan supports Palestinian statehood through the Two-state solution.[118] The ruling Hashemite family has had custodianship over holy sites in Jerusalem since the beginning of the 20th century, a position reinforced in the Israel–Jordan peace treaty. Turmoil in Jerusalem's Al-Aqsa mosque between Israelis and Palestinians created tensions between Jordan and Israel concerning the former's role in protecting the Muslim and Christian sites in Jerusalem.[119]

Jordan is a founding member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and of the Arab League.[120][121] It enjoys "advanced status" with the European Union and is part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims to increase links between the EU and its neighbours.[122] Jordan and Morocco tried to join the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in 2011, but the Gulf countries offered a five-year development aid programme instead.[123]

Military, crime and law enforcement

The first organized army in Jordan was established on 22 October 1920, and was named the "Arab Legion". Jordan's capture of the West Bank during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War proved that the Arab Legion, known today as the Jordan Armed Forces, was the most effective among the Arab troops involved in the war.[63] The Royal Jordanian Army, which boasts around 110,000 personnel, is considered to be among the most professional in the region, due to being particularly well-trained and organized.[63] The Jordanian military enjoys strong support and aid from the United States, the United Kingdom and France. This is due to Jordan's critical position in the Middle East.[63] The development of Special Operations Forces has been particularly significant, enhancing the capability of the military to react rapidly to threats to homeland security, as well as training special forces from the region and beyond.[124] Jordan provides extensive training to the security forces of several Arab countries.[125]

There are about 50,000 Jordanian troops working with the United Nations in peacekeeping missions across the world. Jordan ranks third internationally in participation in U.N. peacekeeping missions,[126] with one of the highest levels of peacekeeping troop contributions of all U.N. member states.[127] Jordan has dispatched several field hospitals to conflict zones and areas affected by natural disasters across the region.[128]

In 2014, Jordan joined an aerial bombardment campaign by an international coalition led by the United States against the Islamic State as part of its intervention in the Syrian Civil War.[129] In 2015, Jordan participated in the Saudi Arabian-led military intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was deposed in the 2011 uprising.[130]

Jordan's law enforcement is under the purview of the Public Security Directorate (which includes approximately 40,000 persons). The Jordanian national police is subordinate to the Public Security Directorate of the Ministry of Interior. The first police force in the Jordanian state was organized after the fall of the Ottoman Empire on 11 April 1921.[131] Until 1956 police duties were carried out by the Arab Legion and the Transjordan Frontier Force. After that year the Public Safety Directorate was established.[131] The number of female police officers is increasing. In the 1970s, it was the first Arab country to include females in its police force.[132] Jordan's law enforcement was ranked 37th in the world and 3rd in the Middle East, in terms of police services' performance, by the 2016 World Internal Security and Police Index.[12][133]

Economy

Jordan is classified by the World Bank as an "upper-middle income" country; however, approximately 14.4% (as of 2010) of the population lives below the national poverty line.[134] The economy, which boasts a GDP of $38.210 billion (as of 2015),[3] grew at an average rate of 4.3% per annum between 2005 and 2010, and around 2.5% 2010 onwards.[135] GDP per capita rose by 351% in the 1970s, declined 30% in the 1980s, and rose 36% in the 1990s.[136] The Jordanian economy is one of the smallest economies in the region, and the country's populace suffers from relatively high rates of unemployment and poverty.[84]

Jordan's economy is relatively well diversified. Trade and finance combined account for nearly one-third of GDP; transportation and communication, public utilities, and construction account for one-fifth, and mining and manufacturing constitute nearly another fifth. Despite plans to expand the private sector, the state remains the dominant force in Jordan's economy.[18] Net official development assistance to Jordan in 2009 totalled USD 761 million; according to the government, approximately two-thirds of this was allocated as grants, of which half was direct budget support.[135]

The official currency is the Jordanian dinar, which is pegged to the IMF's special drawing rights (SDRs), equivalent to an exchange rate of 1 US$ ≡ 0.709 dinar, or approximately 1 dinar ≡ 1.41044 dollars.[137] In 2000, Jordan joined the World Trade Organization and signed the Jordan–United States Free Trade Agreement, thus becoming the first Arab country to establish a free trade agreement with the United States. Jordan also has free trade agreements with Turkey and Canada.[138] Jordan enjoys advanced status with the EU, which has facilitated greater access to export to European markets.[139] Due to slow domestic growth, high energy and food subsidies and a bloated public-sector workforce, Jordan usually runs annual budget deficits. These are partially offset by international aid.[140]

The Great Recession and the turmoil caused by the Arab Spring have depressed Jordan's GDP growth, impacting trade, industry, construction and tourism.[84] Tourist arrivals have dropped sharply since 2011.[141] Jordan's finances have also been severely strained by 32 attacks on the natural gas pipeline in Sinai supplying Jordan from Egypt by Islamic State affiliates, causing it to substitute more expensive heavy-fuel oils to generate electricity.[142] In November 2012, the government cut subsidies on fuel, increasing its price.[143] The decision, which was later revoked, caused large scale protests to break out across the country.[140][141]

Jordan's total foreign debt in 2012 was $22 billion, representing 72% of its GDP.[143] In 2016, the debt reached $35.1 billion representing 90.6% of its GDP. This substantial increase is attributed to effects of regional instability causing; decrease in tourist activity, decreased foreign investments, increased military expenditure, electrical company debts due to attacks on Egyptian pipeline, accumulated interests from loans, the collapse of trade with Iraq and Syria and expenses from hosting Syrian refugees.[78] According to the World Bank, Syrian refugees have cost Jordan more than $2.5 billion a year, amounting to 6% of the GDP and 25% of the government's annual revenue.[144] Foreign aid covers only a small part of these costs, 63% of the total costs are covered by Jordan.[145]

The proportion of skilled workers in Jordan is among the highest in the region in sectors such as ICT and industry, due to a relatively modern educational system. This has attracted large foreign investments to Jordan and has enabled the country to export its workforce to Persian Gulf countries.[16] Flows of remittances to Jordan grew rapidly, particularly during the end of the 1970s and 1980s, and remains an important source of external funding.[146] Remittances from Jordanian expatriates were $3.8 billion in 2015, a notable rise in the amount of transfers compared to 2014 where remittances reached over $3.66 billion listing Jordan as fourth largest recipient in the region.[147]

Industry

Jordan's well developed industrial sector, which includes mining, manufacturing, construction, and power, accounted for approximately 26% of the GDP in 2004 (including manufacturing, 16.2%; construction, 4.6%; and mining, 3.1%). More than 21% of Jordan's labor force was employed in industry in 2002. In 2014, industry accounted for 6% of the GDP.[148] The main industrial products are potash, phosphates, cement, clothes, and fertilizers. The most promising segment of this sector is construction. Petra Engineering Industries Company which is considered to be one of the main pillars of Jordanian industry, has gained international recognition with its air-conditioning units reaching NASA.[149] Jordan is now considered to be a leading pharmaceuticals manufacturer in the MENA region led by Jordanian pharmaceutical company Hikma.[150]

Jordan's military industry thrived after the King Abdullah Design and Development Bureau (KADDB) defence company was established by King Abdullah II in 1999, to provide an indigenous capability for the supply of scientific and technical services to the Jordanian Armed Forces, and to become a global hub in security research and development. It manufactures all types of military products, many of which are presented at the bi-annually held international military exhibition SOFEX. In 2015, KADDB exported $72 million worth of industries to over 42 countries.[151]

Tourism

The tourism sector is considered a cornerstone of the economy, being a large source of employment, hard currency and economic growth. In 2010, there were 8 million visitors to Jordan. The result was $3.4 billion in tourism revenues, $4.4 billion with the inclusion of medical tourists.[152] The majority of tourists coming to Jordan are from European and Arab countries.[17] The tourism sector in Jordan has been severely affected by regional turbulence.[60] The most recent impact to the tourism sector was caused by the Arab Spring, which scared off tourists from the entire region. Jordan experienced a 70% decrease in the number of tourists from 2010 to 2016.[153]

According to the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Jordan is home to around 100,000 archaeological and tourist sites.[154] Some very well preserved historical cities include Petra and Jerash, the former being Jordan's most popular tourist attraction and an icon of the kingdom.[153] Jordan is part of the Holy Land and has several biblical attractions that attract pilgrimage activities. Biblical sites include: Al-Maghtas where Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, Mount Nebo, Umm ar-Rasas, Madaba and Machaerus.[155] Islamic sites include shrines of the prophet Muhammad's companions such as 'Abd Allah ibn Rawahah, Zayd ibn Harithah and Muadh ibn Jabal.[156] Ajlun Castle built by Muslim Ayyubid leader Saladin in the 12th century AD during his wars with the Crusaders, is also a popular tourist attraction.[7]

Modern entertainment and recreation in urban areas, mostly in Amman, also attract tourists. Recently, the nightlife in Amman, Aqaba and Irbid has started to emerge and the number of bars, discos and nightclubs is on the rise. However, most nightclubs have a restriction on unescorted males.[157] Alcohol is widely available in tourist restaurants, liquor stores and even some supermarkets.[158] Valleys like Wadi Mujib and hiking trails in different parts of the country attract adventurers. Moreover, seaside recreation is present in on the shores of Aqaba and the Dead Sea through several international resorts.[159]

Jordan has been a medical tourism destination in the Middle East since the 1970s. A study conducted by Jordan's Private Hospitals Association found that 250,000 patients from 102 countries received treatment in Jordan in 2010, compared to 190,000 in 2007, bringing over $1 billion in revenue. Jordan is the region's top medical tourism destination, as rated by the World Bank, and fifth in the world overall.[160] The majority of patients come from Yemen, Libya and Syria due to the ongoing civil wars in those countries. Jordanian doctors and medical staff have gained experience in dealing with war patients through years of receiving such cases from various conflict zones in the region.[161] Jordan also is a hub for natural treatment methods in both Ma'in Hot Springs and the Dead Sea. The Dead Sea is often described as a 'natural spa'. It contains 10 times more salt than the average ocean, which makes it impossible to sink in. The high salt concentration of the Dead Sea has been proven as therapeutic for many skin diseases. The uniqueness of this lake attracts several Jordanian and foreign vacationers, which boosted investments in the hotel sector in the area.[162]

Natural resources

Jordan is the world's second poorest country in terms of water resources per capita, and scarce water resources were aggravated by the influx of Syrian refugees.[163] Water from Disi aquifer and ten major dams play a large role in providing Jordan's need for fresh water.[164] Phosphate mines in the south have made Jordan one of the largest producers and exporters of this mineral in the world.[165]

Despite the fact that reserves of crude oil are non-commercial, Jordan has the 5th largest oil-shale reserves in the world that could be commercially exploited in the central and northern regions west of the country.[166] Official figures estimate the kingdom's oil shale reserves at more than 70 billion tonnes. Attarat Power Plant is a $2.2 billion oil shale-dependent power plant which will be completed in 2019 with a total capacity of 470 megawatts. The project is part of the kingdom's 2025 vision that aims at diversifying its energy resources.[167] The extraction of oil shale had been delayed by a couple of years due to the advanced level of technology that is required to extract it and its relatively higher cost.[168]

Jordan aims to benefit from its large uranium reserves with two nuclear plants, 1000 MW each, scheduled for completion in 2025.[169] Natural gas was discovered in Jordan in 1987. The estimated size of the reserve discovered was about 230 billion cubic feet, a modest quantity compared with its other Arab neighbours. The Risha field, in the eastern desert beside the Iraqi border, produces nearly 35 million cubic feet of gas a day, which is sent to a nearby power plant to produce nearly 10% of Jordan's electricity needs.[170] Jordan receives 330 days of sunshine per year, and wind speeds reach over 7 m/s over the mountainous areas.[171] For this reason, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources inaugurated several large-scale projects like the Tafila Wind Farm and the Shams Ma'an Power Plant. The ministry have set a target to obtain 10% of Jordan's electrical consumption from renewable resources by 2020.[172]

Transportation

Jordan ranked as having the 35th best infrastructure in the world, one of the highest rankings in the developing world, according to the World Economic Forum's Index of Economic Competitiveness. This high infrastructural development is necessitated by its role as a transit country for goods and services to the Palestine and Iraq. Palestinians use Jordan as a transit country due to the Israeli restrictions and Iraqis use Jordan due to the instability in Iraq.[173]

According to data from the Jordanian Ministry of Public Works and Housing, as of 2011, the Jordanian road network consisted of 2,878 km (1,788 mi) of main roads; 2,592 km (1,611 mi) of rural roads and 1,733 km (1,077 mi) of side roads. The Hejaz Railway built during the Ottoman Empire which extended from Damascus to Mecca will act as a base for future railway expansion plans. Currently, the railway has barely any civilian activity, it is primarily used for transporting goods. A national railway project is currently undergoing studies and seeking funding sources.[174]

Jordan has three commercial airports, all receiving and dispatching international flights. Two are in Amman and the third is in Aqaba, King Hussein International Airport. Amman Civil Airport serves several regional routes and charter flights while Queen Alia International Airport is the major international airport in Jordan and is the hub for Royal Jordanian, the flag carrier. Queen Alia International Airport expansion was completed in 2013 with new terminals costing $700 million, to handle over 16 million passengers annually.[175] It is now considered a state-of-the-art airport and was awarded 'the best airport by region: Middle East' for 2014 and 2015 by Airport Service Quality (ASQ) survey, the world's leading airport passenger satisfaction benchmark program.[176]

The Port of Aqaba is the only port in Jordan. In 2006, the port was ranked as being the "Best Container Terminal" in the Middle East by Lloyd's List. The port was chosen due to it being a transit cargo port for other neighboring countries, its location between four countries and three continents, being an exclusive gateway for the local market and for the improvements it has recently witnessed.[177]

Science and technology

Science and technology is the country's fastest developing economic sector. This growth occurs across multiple industries including Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and nuclear technology. Jordan contributes to 75% of the Arabic content on the Internet.[178] In 2014, the ICT sector accounted for more than 84,000 jobs, and contributed to 12% of the GDP. More than 400 companies are active in telecom, IT and video game development. While there are 600 companies operating in active technologies and 300 startup companies.[178]

Nuclear science and technology is also expanding; nuclear facilities are undergoing construction. Jordan Research and Training Reactor is a 5MW training reactor located in Jordan University of Science and Technology; the reactor will be inaugurated in December 2016 and will be used by the university to train their students in the already existing nuclear engineering program.[179] Jordan signed a contract with Russian company Rosatom in 2014 for the construction of two $5 billion nuclear reactors which are currently under planning and are expected to start delivering electricity in 2025.[169]

Jordan was also selected as the location for the Synchrotron-Light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East (SESAME) facility, which is supported by UNESCO and CERN. This particle accelerator, which is expected to start operations in May 2017, will allow collaboration between scientists across the Middle East despite the political conflicts.[180]

Demographics

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1920 | 200,000 | — |

| 1922 | 225,000 | +6.07% |

| 1948 | 400,000 | +2.24% |

| 1952 | 586,200 | +10.03% |

| 1961 | 900,800 | +4.89% |

| 1979 | 2,133,000 | +4.91% |

| 1994 | 4,139,500 | +4.52% |

| 2004 | 5,100,000 | +2.11% |

| 2015 | 9,531,712 | +5.85% |

| Source: Department of Statistics[181] | ||

The latest census, taken in 2015, showed the population numbered some 9.5 million. 2.9 million (30%) were non-citizens, a figure including refugees and illegal immigrants.[13] There were 1,977,534 households in Jordan in 2015, with an average of 4.8 persons per household (compared to 6.7 persons per household for the census of 1979).[13] The vast majority of Jordanians are Arabs, accounting for 98% of the population. The rest is attributed to Circassians, Chechens and Armenians.[84] As the population has increased, it has become more settled and urban. In 1922 almost half the population (around 103,000) were nomadic, whereas nomads made up only 6% of the population in 2015. The population in Amman, 65,754 in 1946, has grown to over 4 million in 2015.[181]

Immigrants and refugees

Jordan was home to 2,117,361 Palestinians in 2015, most of them Jordanian citizens.[182] The first wave of Palestinian refugees arrived during the 1948 Arab Israeli war and peaked in the 1967 Six Day War and the 1990 Gulf War. In the past, Jordan had given many Palestinian refugees citizenship, however recently Jordanian citizenship is given only in rare cases. 370,000 of these Palestinians live in UNRWA refugee camps.[182] Following the capture of the West Bank by Israel in 1967, Jordan revoked the citizenship of thousands of Palestinians to thwart any attempt to permanently resettle from the West Bank to Jordan. West Bank Palestinians with family in Jordan or Jordanian citizenship were issued yellow cards guaranteeing them all the rights of Jordanian citizenship if requested.[183]

While some 700,000–1,000,000 Iraqis came to Jordan following the Iraq War in 2003, most have returned.[184] Many Iraqi Christians (Assyrians/Chaldeans) however settled temporarily or permanently in Jordan.[185] Immigrants also include 15,000 Lebanese who arrived following the 2006 Lebanon War.[186] Since 2010, over 1.4 million Syrian refugees have fled to Jordan to escape the violence in Syria.[13] The kingdom has continued to demonstrate hospitality, despite the substantial strain the flux of Syrian refugees places on the country. The effects are largely affecting Jordanian communities, as the vast majority of Syrian refugees do not live in camps. The refugee crisis effects include competition for job opportunities, water resources and other state provided services, along with the strain on the national infrastructure.[15]

In 2007, Assyrian Christians accounted for up to 150,000 persons, most are Eastern Aramaic speaking refugees from Iraq.[187] Kurds number some 30,000 people, and like the Assyrians, many are refugees from Iraq, Iran and Turkey.[188] Descendants of Armenians that sought refuge in the Levant during the 1915 Armenian Genocide number approximately 5,000 persons, mainly residing in Amman.[189] A small number of ethnic Mandeans also reside in Jordan, again mainly refugees from Iraq.[190] Around 12,000 Iraqi Christians have sought refuge in Jordan after the Islamic State took the city of Mosul in 2014.[191] Several thousand Libyans, Yemenis and Sudanese have also sought asylum in Jordan to escape instability and violence in their respective countries.[15] The 2015 Jordanian census recorded that there are 1,265,000 Syrians, 636,270 Egyptians, 634,182 Palestinians, 130,911 Iraqis, 31,163 Yemenis, 22,700 Libyans and 197,385 from other nationalities residing in the country.[13]

There are around 1.2 million illegal and some 500,000 legal migrant workers in the kingdom.[192] Thousands of foreign women, mostly from Greater Middle East and Eastern Europe, work in nightclubs, hotels and bars across the kingdom.[193][194][195] American and European expatriate communities are concentrated in the capital, as the city is home to many international organizations and diplomatic missions.[158]

Religion and languages

Sunni Islam is the dominant religion in Jordan. Muslims make up about 92% of the country's population; in turn, 93% of those self-identify as Sunnis—the highest percentage in the world.[196] There are also a small number of Ahmadi Muslims,[197] and some Shiites. Many Shia are Iraqi and Lebanese refugees.[198] Muslims who convert to another religion as well as missionaries from other religions face societal and legal discrimination.[199]

Jordan contains some of the oldest Christian communities in the world, dating as early as the 1st century AD after the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.[200] Christians today make up about 4% of the population,[201] down from 20% in 1930.[14] This is due to high immigration rates of Muslims into Jordan, higher emigration rates of Christians to the west and higher birth rates for Muslims.[202] Jordanian Christians number around 250,000, all of whom are Arabic-speaking, according to a 2014 estimate by the Orthodox Church. The study excluded minority Christian groups and the thousands of western, Iraqi and Syrian Christians residing in Jordan.[201] Christians are exceptionally well integrated in the Jordanian society and enjoy a high level of freedom, though they are not free to evangelize Muslims.[203] Christians traditionally occupy two cabinet posts, and are reserved 9 seats out of the 130 in the parliament.[204] The highest political position reached by a Christian is deputy prime minister, held by Marwan al-Muasher in 2005.[205] Christians are also influential in media.[206] Smaller religious minorities include Druze and Bahá'ís. Most Jordanian Druze live in the eastern oasis town of Azraq, some villages on the Syrian border, and the city of Zarqa, while most Jordanian Bahá'ís live in the village of Adassiyeh bordering the Jordan Valley.[207]

The official language is Modern Standard Arabic, a literary language taught in the schools.[208] Most Jordanians natively speak one of the non-standard Arabic dialects known as Jordanian Arabic. Jordanian Sign Language is the language of the deaf community. English, though without official status, is widely spoken throughout the country and is the de facto language of commerce and banking, as well as a co-official status in the education sector; almost all university-level classes are held in English and almost all public schools teach English along with Standard Arabic.[208] Chechen, Circassian, Armenian, Tagalog, and Russian are popular among their communities.[209] French is elective in many schools, mainly in the private sector.[208] German is an increasingly popular language among the elite and the educated; it's been most likely introduced at a larger scale after the début of the German-Jordanian University in 2005.[210]

Culture

Arts, cinema, museums and music

Many institutions in Jordan aim to increase cultural awareness of Jordanian Art and to represent Jordan's artistic movements in fields such as paintings, sculpture, graffiti and photography.[211] The art scene has been developing in the past few years[212] and Jordan has been a haven for artists from surrounding countries.[213] In January 2016, for the first time ever, a Jordanian film called Theeb was nominated for the Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film.[214]

The largest museum in Jordan is The Jordan Museum. It contains much of the valuable archaeological findings in the country, including some of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Neolithic limestone statues of 'Ain Ghazal and a copy of the Mesha Stele.[215] Most museums in Jordan are located in Amman including the The Children's Museum Jordan, The Martyr's Memorial and Museum and the Royal Automobile Museum. Museums outside Amman include the Aqaba Archaeological Museum.[216] The Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts is a major contemporary art museum located in Amman.[216]

Music in Jordan is now developing with a lot of new bands and artists, who are now popular in the Middle East. Artists such as Omar Al-Abdallat, Toni Qattan and Hani Metwasi have increased the popularity of Jordanian music.[217] The Jerash Festival is an annual music event that features popular Arab singers.[217] Pianist and composer Zade Dirani has gained wide international popularity.[218] There is also an increasing growth of alternative Arabic music bands, who are dominating the scene in the Arab World, including; El Morabba3, Autostrad, JadaL, Akher Zapheer and Ayloul.[219]

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Jordan.[158] The national football team has improved in recent years, though it has yet to qualify for the World Cup.[216] In 2013, Jordan lost a chance to play at the 2014 World Cup when they lost to Uruguay during inter-confederation play-offs. This was the highest that Jordan had advanced in the World Cup qualifying rounds since 1986.[220] The women's football team is also gaining reputation,[221] and in March 2016 ranked 58th in the world.[222] Jordan hosted the 2016 FIFA U-17 Women's World Cup, the first women's sports tournament in the Middle East.[223]

Less common sports are gaining popularity. Rugby is increasing in popularity, a Rugby Union is recognized by the Jordan Olympic Committee which supervises three national teams.[224] Although cycling is not widespread in Jordan, the sport is developing rapidly as a lifestyle and a new way to travel especially among the youth.[225] In 2014, a NGO Make Life Skate Life completed construction of the 7Hills Skatepark, the first skatepark in the country located in Downtown Amman.[226] Jordan's national basketball team is participating in various international and Middle Eastern tournaments. Local basketball teams include: Al-Orthodoxi Club, Al-Riyadi, Zain, Al-Hussein and Al-Jazeera.[227]

Cuisine

As the 8th largest producer of olives in the world, olive oil is the main cooking oil in Jordan.[228] A common appetizer is hummus, which is a puree of chick peas blended with tahini, lemon, and garlic. Ful medames is another well-known appetiser. A typical worker's meal, it has since made its way to the tables of the upper class. A typical Jordanian meze often contains koubba maqliya, labaneh, baba ghanoush, tabbouleh, olives and pickles.[229] Meze is generally accompanied by the Levantine alcoholic drink arak, which is made from grapes and aniseed and is similar to ouzo, rakı and pastis. Jordanian wine and beer are also sometimes used. The same dishes, served without alcoholic drinks, can also be termed "muqabbilat" (starters) in Arabic.[158]

The most distinctive Jordanian dish is mansaf, the national dish of Jordan. The dish is a symbol for Jordanian hospitality and is influenced by the Bedouin culture. Mansaf is eaten on different occasions such as funerals, weddings and on religious holidays. It consists of a plate of rice with meat that was boiled in thick yogurt, sprayed with nuts and sometimes herbs. As an old tradition, the dish is eaten using one's hands, but the tradition is not always used.[229] Simple fresh fruit is often served towards the end of a Jordanian meal, but there is also dessert, such as baklava, hareeseh, knafeh, halva and qatayef, a dish made specially for Ramadan. In Jordanian cuisine, drinking coffee and tea flavored with na'na or meramiyyeh is almost a ritual.[230]

Health and education

Life expectancy in Jordan is around 74.35 years.[84] The leading cause of death is cardiovascular diseases, followed by cancer.[231] Childhood immunization rates have increased steadily over the past 15 years; by 2002 immunizations and vaccines reached more than 95% of children under five.[232] Water and sanitation, available to only 10% of the population in 1950, now reach 98% of Jordanians.[233]

Jordan prides itself on its health services, some of the best in the region.[234] Qualified medics, favorable investment climate and Jordan's stability has contributed to the success of this sector.[235] The country's health care system is divided between public and private institutions. On 1 June 2007, Jordan Hospital (as the biggest private hospital) was the first general specialty hospital to gain the international accreditation JCAHO.[232] The King Hussein Cancer Center is a leading cancer treatment center.[236] 66% of Jordanians have medical insurance.[13]

The Jordanian educational system consists of a two-year cycle of pre-school education, ten years of compulsory basic education, and two years of secondary academic or vocational education, after which the students sit for the Tawjihi exams.[237] 79% of children go through primary education, while secondary school enrollment has increased from 63% to 97% of high school aged students in Jordan. Between 79% and 85% of high school students in Jordan move on to higher education.[238] According to the CIA World Factbook, the literacy rate in 2015 was 95.4%.[84] UNESCO ranked Jordan's education system 18th out of 94 nations for providing gender equality in education.[239] Education is not free in Jordan.[240]

Jordan has 10 public universities, 16 private universities and 54 community colleges, of which 14 are public, 24 private and others affiliated with the Jordanian Armed Forces, the Civil Defense Department, the Ministry of Health and UNRWA.[241] There are over 200,000 Jordanian students enrolled in universities each year. An additional 20,000 Jordanians pursue higher education abroad primarily in the United States and Europe.[242] According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are the University of Jordan (UJ) (1,010th worldwide), Jordan University of Science & Technology (JUST) (1,907th) and Yarmouk University (1,969th).[243] UJ and JUST occupy 8th and 10th between Arab universities.[244] Jordan has 2,000 researchers per million people.[245]

See also

- Human rights in Jordan

- List of World Heritage Sites in Jordan

- Index of Jordan-related articles

- Outline of Jordan

References

- ↑ Temperman, Jeroen (2010). State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law: Towards a Right to Religiously Neutral Governance. Brill. p. 87. ISBN 90-04-18148-2. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ "Population clock". Jordan Department of Statistics. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Jordan". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ "Gini index". World Bank. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ "2015 Human Development Report Summary" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 1 January 2015. pp. 21–25. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- 1 2 McColl, R. W. (14 May 2014). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Infobase Publishing. p. 498. ISBN 9780816072293. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Teller, Matthew (2002). Jordan. Rough Guides. pp. 173, 408. ISBN 9781858287409. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- 1 2 Al-Asad, Mohammad (22 April 2004). "The Domination of Amman Urban Crossroads". CSBE. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "The History of a Land". Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. The Department Of Antiquities (Jordan). Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- 1 2 Khalil, Muhammad (1962). The Arab States and the Arab League: a Documentary Record. Beirut: Khayats. pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 "Jordan". Freedom in the World. Freedom House. 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- 1 2 Dickey, Christopher (5 October 2013). "Jordan: The Last Arab Safe Haven". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ghazal, Mohammad (22 January 2016). "Population stands at around 9.5 million, including 2.9 million guests". The Jordan Times. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- 1 2 Vela, Justin (14 February 2015). "Jordan: The safe haven for Christians fleeing ISIL". The National. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 "2015 UNHCR country operations profile – Jordan". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- 1 2 El-Said, Hamed; Becker, Kip (11 January 2013). Management and International Business Issues in Jordan. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 9781136396366. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Jordan second top Arab destination to German tourists". Petra. Jordan News. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Jordan's Economy Surprises". Washington Institute. Washington Institute. 29 June 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. pp. 467, 928. ISBN 9780865543737. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Aḥituv, Shmuel (1984). Canaanite toponyms in ancient Egyptian documents. Magnes Press. p. 123. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "اردن الشموخ والحضارة...اصل التسمية" [Jordan's civilization.. Etymology] (in Arabic). Jordan Zad. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ al-Nahar, Maysoun (11 June 2014). "The First Traces of Man. The Palaeolithic Period (<1.5 million – ca 20,000 years ago)". In Ababsa, Myriam. Atlas of Jordan. pp. 94–99. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- 1 2 Patai, Raphael (8 December 2015). Kingdom of Jordan. Princeton University Press. pp. 23, 32. ISBN 9781400877997. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ↑ "Archaeologists discover Jordan's earliest buildings". University of Cambridge. 18 February 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ "The Paleolithic Period 1,500,000–21,000 BC". Jordan Department of Antiquities. Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ Kafafi, Zeidan (11 June 2014). "Ayn Ghazal. A 10,000 year-old Jordanian village". In Ababsa, Myriam. Atlas of Jordan. pp. 111–113. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ Betts, Alison (March 2014). "The Southern Levant (Transjordan) During the Neolithic Period". Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199212972.013.012. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "Lime Plaster statues". British Museum. Trustees of the British Museum. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

Dating to the end of the eighth millennium BC, they are among the earliest large-scale representations of the human form.

- ↑ Feldman, Keffie. "Ain-Ghazal (Jordan) Pre-pottery Neolithic B Period pit of lime plaster human figures". Joukowsky Institute, Brown University. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ Richard, Suzanne (2003). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader. Eisenbrauns. p. 264. ISBN 9781575060835. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ↑ Insoll, Timothy (27 October 2011). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion. Oxford University Presss. p. 896. ISBN 9780199232444. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- 1 2 LaBianca, Oystein S.; Younker, Randall W. (1995). "The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab, and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (ca. 1400–500 BCE)". In Thomas Levy. The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Leicester University Press. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- 1 2 "The Mesha Stele". Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Levant. Louvre Museum. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Harrison, Timothy P. (2009), "`The land of Medeba' and Early Iron Age Mādabā", in Bienkowski, Piotr, Studies on Iron Age Moab and Neighbouring Areas: In Honour of Michèle Daviau (PDF), Leuven: Peeters, pp. 27–45, retrieved 30 June 2016

- ↑ Rollston, Chris A. (2010). Writing and Literacy in the World of Ancient Israel: Epigraphic Evidence from the Iron Age. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 54. ISBN 9781589831070. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Hill, Andrew E.; Walton, John H. (11 May 2010). A Survey of the Old Testament. Harper Collins. p. 1964. ISBN 9780310590668. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Salibi, Kamal (1998). The Modern History of Jordan. I.B.Tauris. pp. 10, 30, 31, 49, 104. ISBN 978-1-86064-331-6. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Taylor, Jane (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. I.B.Tauris. pp. 11, 47. ISBN 9781860645082. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Holloway, April (8 August 2014). "Oldest Arabic inscription provides missing link between Nabataean and Arabic writing". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ Schumacher, Gottlieb (19 August 2010). Northern 'Ajlun, 'within the Decapolis'. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9781108017572. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Shilin, Mikhail. "Fishing for Sustainable Living in Aqaba, Red Sea, Jordan: pre-project report". UNESCO. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Walker, Jenny; Firestone, Matthew (2009). Jordan. Lonely Planet. pp. 26, 39–41. ISBN 9781742203546. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Gates, Charles (15 April 2013). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Routledge. p. 393. ISBN 9781134676620. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ "First purpose-built church". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ↑ "Um er-Rasas (Kastrom Mefa'a)". UNESCO. 1 January 2004. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Rimon, Ofra (1 May 2010). "The Nabateans in the Negev". Hecht Museum. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ Avni, Gideon (30 January 2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. OUP Oxford. p. 302. ISBN 9780191507342. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Bowersock, G. W.; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (1999). Late Antiquity: A guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780674511736. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- 1 2 "The History of a Land". Jordan Department of Antiquities. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Altman, Jack (1 March 2003). Jordan. Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 9782884521116. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Daly, M. W.; Petry, Carl (1998). The Cambridge history of Egypt. Cambridge University Press. p. 498. ISBN 9780521471374.

- 1 2 Rogan, Eugene; Tell, Tariq (1994). Village, Steppe and State: The Social Origins of Modern Jordan. British Academic Press. pp. 37, 47. ISBN 9781850438298. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- 1 2 Rogan, Eugene (11 April 2002). Frontiers of the State in the Late Ottoman Empire: Transjordan, 1850–1921. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780521892230. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- 1 2 Milton-Edwards, Beverley; Hinchcliffe, Peter (5 June 2009). Jordan: A Hashemite Legacy. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134105465. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- 1 2 Laura, Perdew (1 November 2014). Understanding Jordan Today. Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9781612286778. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Moore, Pete (14 October 2004). Doing Business in the Middle East: Politics and Economic Crisis in Jordan and Kuwait. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9781139456357. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ N’Diaye, Cordu (9 October 2014). "Hijaz Railway a reminder of old Hajj traditions". The Jordan Times. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Metz, Helen Chapin (1991). Jordan: A country study. Country Studies. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 53–56.

- ↑ Herb, Michael (27 May 1999). All in the Family: Absolutism, Revolution, and Democracy in Middle Eastern Monarchies. SUNY Press. p. 278. ISBN 9780791441688. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- 1 2 H. Joffé, E. George (2002). Jordan in Transition. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 212, 308. ISBN 9781850654889. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Sicker, Martin (2001). The Middle East in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-275-96893-9. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Browne, O'Brien (10 August 2010). "Creating Chaos: Lawrence of Arabia and the 1916 Arab Revolt". HistoryNet, LLC. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Tucker, Spencer (10 August 2010). "The Encyclopedia of Middle East Wars: The United States in the Persian Gulf". ABC-CLIO. p. 662. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ League of Nations Official Journal, Nov. 1922, pp. 1188–1189, 1390–1391.

- ↑ Marjorie M. Whiteman, Digest of International Law, vol. 1, U.S. State Department (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963) pp 636, 650–652

- ↑ Foreign relations of the United States, 1946. The Near East and Africa, Vol. 7. United States Department of State. 1946. pp. 794–800. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Aruri, N.H. (1972). Jordan: a study in political development (1921–1965). Springer Netherlands. p. 90. ISBN 978-90-247-1217-5. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Morris, Benny (1 October 2008). A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. pp. 214, 215. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ Aruri, Naseer Hasan (1972). Jordan: a study in political development (1921–1965). Springer. p. 90. ISBN 978-90-247-1217-5. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ El-Hasan, Hasan Afif (2010). Israel Or Palestine? Is the Two-state Solution Already Dead?: A Political and Military History of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict. Algora Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-87586-793-9. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ "Assassination of King Abdullah". The Guardian. 21 July 1951. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Makdisi, Samir; Elbadawi, Ibrahim (2011). Democracy in the Arab World: Explaining the Deficit. IDRC. p. 91. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce (3 January 1990). "Jordan and Iraq: Efforts at Intra-Hashimite Unity". Middle Eastern Studies. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. pp. 65–75. JSTOR 4283349.