Homer G. Phillips Hospital

|

Homer G. Phillips Hospital | |

|

Homer G. Phillips Hospital | |

| |

| Location |

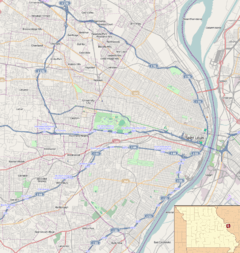

2601 N. Whittier Street. St. Louis, MO, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°39′31″N 90°14′10″W / 38.65861°N 90.23611°WCoordinates: 38°39′31″N 90°14′10″W / 38.65861°N 90.23611°W |

| Area | 10 acres |

| Built | 1932-1936 |

| Architect | Albert Osburg |

| Architectural style | Art deco |

| NRHP Reference # | 82004738 |

Homer G. Phillips Hospital was a hospital located at 2601 N. Whittier Street in The Ville neighborhood of St. Louis, Missouri. It was the city's only hospital for African-Americans from 1937 until 1955, when city hospitals were desegregated, and continued to serve the black community of St. Louis until its closure in 1979. While in operation, it was one of the few hospitals in the United States where black Americans could train as doctors and nurses, and by 1961, Homer G. Phillips Hospital had trained the "largest number of black doctors and nurses in the world."[1] It closed as a full-service hospital in 1979. While vacant, it was listed as a St. Louis Landmark in 1980 and on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. It reopened as senior living apartments in 2003.

History

Construction

Between 1910 and 1920, the black population of St. Louis increased by sixty percent, yet the public City Hospital was segregated, with no facilities for black patients or staff. Thus, a group of black community members persuaded the city in 1919 to purchase a 177-bed hospital (formerly owned by the Barnes Medical College) at Garrison and Lawson avenues on the north side of the city.[2] This hospital, denoted City Hospital #2, was inadequate to the needs of more than 70,000 black St. Louisans, and local black attorney Homer G. Phillips led a campaign for a civic improvements bond issue that would provide for the construction of a larger black hospital.[1]

When the bond issue was passed in 1923, the city refused to allocate funding for the hospital, instead advocating a segregated addition to the original City Hospital, located far from the black community in the Peabody-Darst-Webbe neighborhood. Phillips again led the efforts for the original plan, successfully debating the St. Louis Board of Aldermen for allocation of funds toward a new hospital. Site acquisition resulted in the purchase of 6.3 acres in the Ville, the center of the black community of St. Louis.[1] However, before construction could begin, the leader of the push for the hospital, Homer G. Phillips, was shot and killed. Although two men were arrested and charged with the crime, they were acquitted and Phillips' murder remains unsolved.[3]

Construction on the site began in October 1932, initially using funds from the 1923 bond issue and later from the newly formed Public Works Administration.[4] City architect Albert Osburg was the primary designer of the building, which was completed in phases. The central building was finished between 1933 and 1935, while the two wings were finished between 1936 and 1937. The hospital was dedicated on February 22, 1937, with a parade and speeches by Missouri Governor Lloyd C. Stark, St. Louis Mayor Bernard Francis Dickmann, and Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes.[1] Speaking to the black community of St. Louis, Ickes noted that the hospital would help the community "achieve your rightful place in our economic system."[1] It was renamed from City Hospital #2 in honor of Homer G. Phillips in 1942.[3]

Operation

Although by 1944 the hospital ranked among the ten largest general hospitals in the United States, it was consistently underfunded and understaffed. By 1948, its medical residents included more than one third of all graduates from the two American black medical schools, including Dr. Helen Elizabeth Nash. In the 1940s and 1950s it was a leader in developing the practice of intravenous feeding and treatments for gunshot wounds, ulcers, and burns. Not only did it house a nursing school, but also schools for training x-ray technicians, laboratory technicians and medical record-keeping. It also began offering training and work to foreign doctors who were being denied by other hospitals because of their race.[1]

After a 1955 order by Mayor Raymond Tucker to desegregate city hospitals, Homer G. Phillips began admitting patients regardless of race, color or religious beliefs. However, it remained a primarily black institution into the 1960s. In 1960, each department of the hospital was staffed by at least one black doctor who also was a staff member of either Washington University in St. Louis or Saint Louis University, and in 1962, three-fourths of the interns at the hospital were black.

Closure

As early as 1961, proposals to merge Homer G. Phillips with City Hospital were being made. Although some leaders in the black community opposed the idea (such as William Lacy Clay, Sr., then a city alderman and later U.S. representative for Missouri's 1st district), others accepted the notion.[5] Local NAACP official Ernest Calloway said, "Giving up the hospital may be the price we have to pay for an integrated community."[5] By the mid-1960s, efforts were underway to reduce services at the hospital or close it entirely.[1] In the late 1960s, St. Louis city moved the neurological and psychiatric departments of Homer G. Phillips to City Hospital, citing the low pay at Homer G. Phillips and distance from Washington University staff who were affiliated with City Hospital as reasons for the move.[1]

From 1964 until 1979, no other departments were moved. However, on August 17, 1979, St. Louis abruptly closed all departments at Homer G. Phillips Hospital except for a small outpatient care clinic housed in an adjacent building. The closure brought about significant protests and required more than a hundred police officers to escort remaining patients out.[6] William Lacy Clay, Sr. again led opposition to the closure, and many in the community charged that the closure was racially motivated.[7] Picketing and protests outside the hospital continued for more than a year after the closure, and a community group called Campaign for Human Dignity was formed to continue the movement.[7] Mayor James F. Conway commissioned a task force to study the issue of the hospital, but nothing resulted of the plan, and the protests were ultimately unsuccessful in reopening the hospital.[7]

In the midst of the protests, the hospital was listed by the St. Louis Board of Aldermen as a St. Louis Landmark in February 1980.[8] In 1981, after a contentious primary with incumbent Mayor Conway, Alderman Vincent Schoemehl was elected mayor of St. Louis on a campaign promising to reopen Homer G. Phillips.[7] Instead, Schoemehl deferred to the Conway task force.[7][9] The next year, the hospital was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982 for its significance in architecture, education and to black history.[1] In spite of the listing, in June 1985 Schoemehl ordered the closure of all municipal hospital services, both at City Hospital and at the clinic at Homer G. Phillips.[7] St. Louis area public hospital services were consolidated in nearby Clayton, Missouri, and the Homer G. Phillips complex became entirely vacant.[9]

Renovation

In 1988, a developer named William Thomas began negotiations to turn the former Homer G. Phillips Hospital into a nursing home, but these efforts failed when agreements to lease the property stalled.[9] The property was abandoned until 1991, when the city reopened the adjacent clinic, and the nurses' building behind the main hospital also was reopened as an addition to Annie Malone Children's Home.[9] However, the main building remained vacant.[9] In 1998, the daughter of William Thomas, Sharon Thomas Robnett, renewed negotiations to turn the building into a low-income nursing home and apartments for the elderly, and successfully signed a 99-year lease on the property.[10]

In December 2001, renovations began on the main building through Robnett's development company, W.A.T. Dignity Corp., continuing through July 2003.[9] The renovation project, led by architects of the Fleming Corporation, cost more than $42 million and produced a 220-unit supervised facility for the elderly, named Homer G. Phillips Dignity House.[11] In response to focus groups, the developers upgraded security measures at the site, including adding a perimeter fence, surveillance cameras, and remote keyless entry.[11] In addition to including apartments for the elderly, the facility provides adult daycare, respite care, pharmacy, mental health and substance abuse treatment programs.[10]

Architecture

The original Homer G. Phillips complex includes a main central building, four wards connected to the central building (forming an X shape), a service and power plant building, and a nurses' residence behind the main building. The original facade of the central building was modified with a canopy entrance extension of the emergency room facilities, obscuring the first three stories of the building. All buildings in the complex are yellow brick with terra cotta trim.[1]

Although many hospitals were constructed in the 1920s as skyscrapers, Homer G. Phillips was designed with seven stories to fit within the scale of the Ville neighborhood. A variety of roof shapes and polygonal ends on the patient wards add to the design of the building. The detailing on the building's exterior consists of a red granite base and terra cotta trim around windows and as a horizontal course around the buildings. Original secondary buildings such as the nurses' building and lecture halls (connected to the main building via tunnel) are included as the part of hospital's designation on the National Register of Historic Places. However, a detached clinic built in 1960 is not included.[1]

Controversy

An Associated Press article claims 18 women suspect that babies they were told died during birth at Homer G. Phillips Hospital are actually alive.[12] Albert Watkins, an attorney at law, says that the births occurred from the mid-1950s to the mid—1960s, that all of the mothers were black and poor, mostly from ages 15 to 20, and that in every case a nurse told the mother that her child had died but that she could not view the child's body.

See also

- History of St. Louis, Missouri

- List of hospitals of St. Louis, Missouri

- National Register of Historic Places listings in St. Louis (city, A–L), Missouri

- Racial segregation in the United States

- Race and health

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Homer G. Phillips Hospital" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 1982-09-23.

- ↑ http://beckerarchives.wustl.edu/?p=collections/findingaid&id=8693&q=&rootcontentid=38394

- 1 2 Clayton, Edward T. (September 1977). "The Strange Murder of Homer G. Phillips". Ebony. pp. 160–164. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Tandy Community Center" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 1999-09-17.

- 1 2 "Integration Threatens to Close St. Louis Hospital". Jet. October 26, 1961. p. 51. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- ↑ Wright, John (2002). Discovering African American St. Louis: A Guide to Historic Sites. St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri Historical Society Press. ISBN 1-883982-45-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stein, Lana (1991). Holding Bureaucrats Accountable: Politicians and Professionals in St. Louis. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. pp. 72–75.

- ↑ "Homer G. Phillips Hospital St. Louis Landmark listing". St. Louis City Cultural Resources Office. St. Louis City.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Allen, Michael (February 22, 2005). "Short History of Homer G. Phillips Hospital". Preservation Research Office. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- 1 2 Manning, Margie (March 14, 1999). "$32 million apartments, care center planned for Homer G. site". St. Louis Business Journal. Retrieved Jan 20, 2011.

- 1 2 Terry, John (January 30, 2005). "Homer G. Phillips senior center has waiting list". St. Louis Business Journal. Retrieved Jan 20, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/18-women-suspect-that-babies-they-were-told-died-are-alive/ar-BBj1Fsj?ocid=MSIDHP. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Further reading

- Early, Gerald Lyn (1998). Ain't But a Place: An Anthology of African American Writings about St. Louis. St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri Historical Society Press. ISBN 1-883982-27-8.

External links

- Was former St. Louis hospital site for baby-selling ring?

- Architectural history and photographs of Homer G. Phillips before, during and after renovation

- Architect and preservationist Michael Allen's site on Homer G. Phillips Hospital