History of New York City

| History of New York City |

|---|

|

Lenape and New Netherland, to 1664 New Amsterdam British and Revolution, 1665–1783 Federal and early American, 1784–1854 Tammany and Consolidation, 1855–97 (Civil War, 1861–65) Early 20th century, 1898–1945 Post–World War II, 1946–77 Modern and post-9/11, 1978– |

| See also |

|

Timelines: NYC • Bronx • Brooklyn • Queens • Staten Island Category |

| City of New York Population by year[1][2][3] | |

|---|---|

| 1656 | 1,000 |

| 1690 | 6,000 |

| 1790 | 33,131 |

| 1800 | 60,515 |

| 1810 | 96,373 |

| 1820 | 123,706 |

| 1830 | 202,589 |

| 1840 | 312,710 |

| 1850 | 515,547 |

| 1860 | 813,669 |

| 1870 | 942,292 |

| 1880 | 1,206,299 |

| 1890 | 1,515,301 |

| 1900 | 3,437,202 |

| 1910 | 4,766,883 |

| 1920 | 5,620,048 |

| 1930 | 6,930,446 |

| 1940 | 7,454,995 |

| 1950 | 7,891,957 |

| 1960 | 7,781,984 |

| 1970 | 7,894,862 |

| 1980 | 7,071,639 |

| 1990 | 7,322,564 |

| 2000 | 8,008,278 |

| 2010 | 8,175,133 |

| Including the "outer boroughs" before the 1898 consolidation | |

| 1790 | 49,000 |

| 1800 | 79,200 |

| 1830 | 242,300 |

| 1850 | 696,100 |

| 1880 | 1,912,000 |

Written documentation of New York City's history began with the first European visitor Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524. European settlement began with the Dutch in 1609.

The "Sons of Liberty" destroyed British authority in the city, and the Stamp Act Congress of representatives from throughout the Thirteen Colonies met in the city in 1765 to organize resistance to British policies. The city's strategic location and status as a major seaport made it the prime target for British seizure in 1776. General George Washington lost a series of battles from which he narrowly escaped (with the notable exception of the Battle of Harlem Heights, his first victory of the war), and the British Army controlled New York City and made it their base on the continent until late 1783, attracting Loyalist refugees. The city served as the national capital under the Articles of Confederation from 1785-1789, and briefly served as the new nation's capital in 1789–90 under the United States Constitution that replaced it. Under the new government the city hosted the inauguration of George Washington as the first President of the United States, the drafting of the United States Bill of Rights, and the first Supreme Court of the United States. The opening of the Erie Canal gave excellent steamboat connections with upstate New York and the Great Lakes, along with coastal traffic to lower New England, making the city the preeminent port on the Atlantic Ocean. The arrival of rail connections to the north and west in the 1840s and 1850s strengthened its central role.

Beginning in the mid-19th century, waves of new immigrants arrived from Europe dramatically changing the composition of the city and serving as workers in the expanding industries. Modern New York City traces its development to the consolidation of the five boroughs in 1898 and an economic and building boom following the Great Depression and World War II. Throughout its history, New York City has served as a main port of entry for many immigrants, and its cultural and economic influence has made it one of the most important urban areas in the United States and the world.

Native American settlement

The area that eventually encompassed modern day New York City was inhabited by the Lenape people. These groups of culturally and linguistically identical Native Americans traditionally spoke an Algonquian language now referred to as Unami. Early European settlers called bands of Lenape by the Unami place name for where they lived, such as "Raritan" in Staten Island and New Jersey, "Canarsee" in Brooklyn, and "Hackensack" in New Jersey across the Hudson River from Lower Manhattan. Eastern Long Island neighbors were culturally and linguistically more closely related to the Mohegan-Pequot peoples of New England who spoke the Mohegan-Montauk-Narragansett language.[4]

These people all made use of the abundant waterways in the New York City region for fishing, hunting trips, trade, and occasionally war. Place names such as Raritan Bay and Canarsie, are derived from Lenape names. Many paths created by the indigenous peoples are now main thoroughfares, such as Broadway in Manhattan, the Bronx, and Westchester.[5] The Lenape developed sophisticated techniques of hunting and managing their resources. By the time of the arrival of Europeans, they were cultivating fields of vegetation through the slash and burn technique, which extended the productive life of planted fields. They also harvested vast quantities of fish and shellfish from the bay.[6] Historians estimate that at the time of European settlement, approximately 5,000 Lenape lived in 80 settlements around the region.[7] [8]

European settlement

The first European visitor to the area was Giovanni da Verrazzano, in command of the French ship La Dauphine in 1524. It is believed he sailed into Upper New York Bay, where he encountered native Lenape, returned through The Narrows, where he anchored the night of April 17, and left to continue his voyage. He named the area of present-day New York City Nouvelle-Angoulême (New Angoulême) in honor of Francis I, King of France of the royal house of Valois-Angoulême.[9][10]

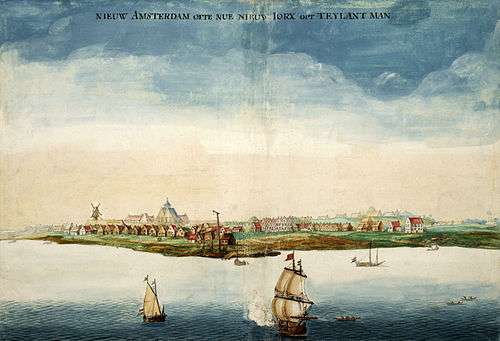

European exploration continued on September 2, 1609, when the Englishman Henry Hudson, in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, sailed the Half Moon through The Narrows into Upper New York Bay. Like Christopher Columbus, Hudson was looking for a westerly passage to Asia. He never found one, but he did take note of the abundant beaver population. Beaver pelts were in fashion in Europe, fueling a lucrative business. Hudson's report on the regional beaver population served as the impetus for the founding of Dutch trading colonies in the New World, among them New Amsterdam (Nieuw Amsterdam), which became New York City in 1664. The beaver's importance in New York City's history is reflected by its use on the city's official seal.

European settlement began with the founding of a Dutch fur trading post in Lower Manhattan at the southern tip of Manhattan in 1624-1625.[11] Soon thereafter, most likely in 1626, construction of Fort Amsterdam began.[11] Later, the Dutch West Indies Company imported African slaves to serve as laborers; they helped to build the wall that defended the town against English and Indian attacks. Early directors included Willem Verhulst and Peter Minuit. Willem Kieft became director in 1638 but five years later was embroiled in Kieft's War against the Native Americans. The Pavonia Massacre, across the Hudson River in present-day Jersey City resulted in the death of 80 natives in February 1643. Following the massacre, Algonquian tribes joined forces and nearly defeated the Dutch. Holland sent additional forces to the aid of Kieft, leading to the overwhelming defeat of the Native Americans and a peace treaty on August 29, 1645.[12]

On May 27, 1647, Peter Stuyvesant was inaugurated as director general upon his arrival and ruled as a member of the Dutch Reformed Church. The colony was granted self-government in 1652, and New Amsterdam was incorporated as a city on February 2, 1653.[13] The first mayors (burgemeesters) of New Amsterdam, Arent van Hattem and Martin Cregier, were appointed in that year.[14]

British and revolution: 1664–1783

In 1664, the English conquered the area and renamed it "New York" after the Duke of York.[15] At that time, people of African descent made up 20% of the population of the city, with European settlers numbering approximately 1,500,[16] and people of African descent numbering 375 (with 300 of that 375 enslaved and 75 free).[17] (Though it has been claimed that African slaves comprised 40% of the small population of the city at that time,[18] this claim has not been substantiated.) During the mid 1600s, farms of free blacks covered 130 acres (53 ha) where Washington Square Park later developed.[19] The Dutch briefly regained the city in 1673, renaming the city "New Orange", before permanently ceding the colony of New Netherland to the English for what is now Suriname in November 1674. Some place names originated in the Dutch period and were named after places in the Netherlands, most notably Flushing (Dutch town of Vlissingen), Harlem (Dutch town of Haarlem) and Brooklyn (Dutch town of Breukelen). Few buildings, however, remain from the 17th century. The oldest recorded house still in existence in New York City, the Pieter Claesen Wyckoff House in Brooklyn, dates from 1652.

The new English rulers of the formerly Dutch New Amsterdam and New Netherland renamed the settlement New York. As the colony grew and prospered, sentiment also grew for greater autonomy. In the context of the Glorious Revolution in England, Jacob Leisler led Leisler's Rebellion and effectively controlled the city and surrounding areas from 1689–1691, before being arrested and executed.

By 1700, the Lenape population of New York had diminished to 200.[7] The Dutch West Indies Company transported African slaves to the post as trading laborers. By the late 17th century, 40% of the settlers were African slaves. They helped build the fort and stockade, and some gained freedom under the Dutch. After the English took over the colony and city they called New York in 1664, they continued to import slaves from Africa and the Caribbean. In 1703, 42% of the New York households had slaves; they served as domestic servants and laborers but also became involved in skilled trades, shipping and other fields. By the 1770s slaves made up less than 25% of the city's population.[20]

The 1735 libel trial of John Peter Zenger in the city was a seminal influence on freedom of the press in North America. It became the standard for the basic articles of freedom in the United States Declaration of Independence.

By the 1740s, 20% of the residents of New York were slaves,[21] totaling about 2,500 people.[22]

After a series of fires in 1741, the city became panicked that blacks planned to burn the city in a conspiracy with some poor whites. Historians believe their alarm was mostly fabrication and fear, but officials rounded up 31 blacks and 4 whites, who over a period of months were convicted of arson. Of these, the city executed 13 blacks by burning them alive and hanged 4 whites and 18 blacks.[23]

In 1754, Columbia University was founded under charter by George II of Great Britain as King's College in Lower Manhattan.[24]

American Revolution

The Stamp Act and other British measures fomented dissent, particularly among Sons of Liberty who maintained a long-running skirmish with locally stationed British troops over Liberty Poles from 1766 to 1776. The Stamp Act Congress met in New York City in 1765 in the first organized resistance to British authority across the colonies. After the major defeat of the Continental Army in the Battle of Long Island in late 1776, General George Washington withdrew to Manhattan Island, but with the subsequent defeat at the Battle of Fort Washington the island was effectively left to the British. The city became a haven for loyalist refugees, becoming a British stronghold for the entire war. Consequently, the area also became the focal point for Washington's espionage and intelligence-gathering throughout the war.

New York City was greatly damaged twice by fires of suspicious origin during British military rule. The city became the political and military center of operations for the British in North America for the remainder of the war and a haven for Loyalist refugees. Continental Army officer Nathan Hale was hanged in Manhattan for espionage. In addition, the British began to hold the majority of captured American prisoners of war aboard prison ships in Wallabout Bay, across the East River in Brooklyn. More Americans lost their lives from neglect aboard these ships than died in all the battles of the war. British occupation lasted until November 25, 1783. George Washington triumphantly returned to the city that day, as the last British forces left the city.

Federal and early America: 1784–1854

Starting in 1785 the Congress met in New York City under the Articles of Confederation. In 1789, New York City became the first national capital of the United States under the new United States Constitution. The Constitution also created the current Congress of the United States, and its first sitting was at Federal Hall on Wall Street. The first United States Supreme Court sat there. The United States Bill of Rights was drafted and ratified there. George Washington was inaugurated at Federal Hall.[25] New York City remained the capital of the U.S. until 1790, when the role was transferred to Philadelphia.

New York grew as an economic center, first as a result of Alexander Hamilton's policies and practices as the first Secretary of the Treasury and, later, with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, which connected the Atlantic port to the vast agricultural markets of the North American interior.[26][27] Immigration resumed after being slowed by wars in Europe, and a new street grid system expanded to encompass all of Manhattan.

In 1842, water was piped from a reservoir to supply the city, for the first time.[28]

The Great Irish Famine (1845-1850) brought a large influx of Irish immigrants, and by 1850 the Irish comprised one quarter of the city's population.[29] Government institutions, including the New York City Police Department and the public schools, were established in the 1840s and 1850s to respond to growing demands of residents.[30]

Modern history

Tammany and consolidation: 1855–1897

This period started with the 1855 inauguration of Fernando Wood as the first mayor from Tammany Hall, an Irish immigrant-supported Democratic Party political machine that dominated local politics throughout this period and into the 1930s.[31] During the 19th century, the city was transformed by immigration, a visionary development proposal called the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, which expanded the city street grid to encompass all of Manhattan, and the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, which connected the Atlantic port to the vast agricultural markets of the Midwestern United States and Canada. By 1835, New York City had surpassed Philadelphia as the largest city in the United States. Public-minded members of the old merchant aristocracy pressed for a Central Park, which was opened to a design competition in 1857; it became the first landscape park in an American city.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), the city was affected by its history of strong commercial ties to the South; before the war, half of its exports were related to cotton, including textiles from upstate mills. Together with its growing immigrant population, which was angry about conscription, sympathies among residents were divided for both the Union and Confederacy at the outbreak of war. Tensions related to the war culminated in the Draft Riots of 1863 by ethnic white immigrants, who attacked black neighborhood and abolitionist homes.[32] Many blacks left the city and moved to Brooklyn. After the Civil War, the rate of immigration from Europe grew steeply, and New York became the first stop for millions seeking a new and better life in the United States, a role acknowledged by the dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1886.

Early 20th century: 1898–1945

From 1890 to 1930, the larger cities were the focus of national attention. The skyscrapers and tourist attractions were widely publicized. Suburbs existed, but they were largely bedroom communities for commuters to the central city. San Francisco dominated the West, Atlanta dominated the South, Boston dominated New England; Chicago, the nation's railroad hub, dominated the Midwest United States; however, New York City dominated the entire nation in terms of communications, trade, finance, popular culture, and high culture. More than a fourth of the 300 largest corporations in 1920 were headquartered in New York City.[33]

In 1898, the modern City of New York was formed with the consolidation of Brooklyn (until then an independent city), Manhattan, and outlying areas.[34] Manhattan and the Bronx were established as two separate boroughs and joined together with three other boroughs created from parts of adjacent counties to form the new municipal government originally called "Greater New York". The Borough of Brooklyn incorporated the independent City of Brooklyn, recently joined to Manhattan by the Brooklyn Bridge; the Borough of Queens was created from western Queens County (with the remnant established as Nassau County in 1899); and The Borough of Richmond contained all of Richmond County. Municipal governments contained within the boroughs were abolished, and the county governmental functions were absorbed by the City or each borough.[35] In 1914, the New York State Legislature created Bronx County, making five counties coterminous with the five boroughs.

The Bronx had a steady boom period during 1898–1929, with a population growth by a factor of six from 200,000 in 1900 to 1.3 million in 1930. The Great Depression saw a surge of unemployment, especially among the working class, and a slowing of growth. After a short war boom, The Bronx declined from 1950–85, going from predominantly moderate-income to mostly lower-income, with high rates of violent crime and poverty. The Bronx has experienced an economic and developmental resurgence starting in the late 1980s that continues into today.[36][37]

On June 15, 1904 over 1,000 people, mostly German immigrant women and children, were killed when the excursion steamship General Slocum caught fire and sank. It is the city's worst maritime disaster. On March 25, 1911 the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in Greenwich Village took the lives of 146 garment workers. In response, the city made great advancements in the fire department, building codes, and workplace regulations.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the city became a world center for industry, commerce, and communication, marking its rising influence with such events as the Hudson-Fulton Celebration of 1909. Interborough Rapid Transit (the first New York City Subway company) began operating in 1904, and the railroads operating out of Grand Central Terminal and Pennsylvania Station thrived.

The city was a destination for internal migrants as well as immigrants. Through 1940, New York City was a major destination for African Americans during the Great Migration from the rural American South. The Harlem Renaissance flourished during the 1920s and the era of Prohibition. New York City's ever accelerating changes and rising crime and poverty rates were reduced after World War I disrupted trade routes, the Immigration Restriction Acts limited additional immigration after the war, and the Great Depression reduced the need for new labor. The combination ended the rule of the Gilded Age barons. As the city's demographics temporarily stabilized, labor unionization helped the working class gain new protections and middle-class affluence, the city's government and infrastructure underwent a dramatic overhaul under Fiorello La Guardia, and his controversial parks commissioner, Robert Moses, ended the blight of many tenement areas, expanded new parks, remade streets, and restricted and reorganized zoning controls.

.svg.png)

For a while, New York City ranked as the most populous city in the world, overtaking London in 1925, which had reigned for a century.[39] During the difficult years of the Great Depression, the reformer Fiorello La Guardia was elected as mayor and Tammany Hall fell after eighty years of political dominance.[40]

Despite the effects of the Great Depression, some of the world's tallest skyscrapers were built during the 1930s, including Art-Deco masterpieces that are still part of the city's skyline today, such as the iconic Chrysler and Empire State buildings. Both before and especially after World War II, vast areas of the city were also reshaped by the construction of bridges, parks and parkways coordinated by Moses, the greatest proponent of automobile-centered modernist urbanism in America.

Post–World War II: 1946–1977

Returning World War II veterans and immigrants from Europe created a postwar economic boom. Demands for new housing were aided by the G.I. Bill for veterans, stimulating the development of huge suburban tracts in eastern Queens and Nassau County. The city was extensively photographed during the post–war years by photographer Todd Webb, who used a heavy camera and tripod.[41]

New York emerged from the war as the leading city of the world, with Wall Street leading the United States ascendancy. In 1951 the United Nations relocated from its first headquarters in Flushing Meadows Park, Queens, to the East Side of Manhattan.[42] During the late 1960s, the views of real estate developer and city leader Robert Moses began to fall out of favor as the anti-urban renewal views of Jane Jacobs gained popularity. Citizen rebellion killed a plan to construct an expressway through lower Manhattan.

The transition away from the industrial base toward a service economy picked up speed while the jobs in the large shipbuilding and garment industries declined sharply. The ports converted to container ships, costing many traditional jobs among longshoremen. Many large corporations moved their headquarters to the suburbs, or to distant cities. At the same time, there was enormous growth in services especially finance, education, medicine, tourism, communications and law. New York remained the largest city, and largest metropolitan area, in the United States, and continued as its largest financial, commercial, information, and cultural center.

Like many major U.S. cities, New York suffered race riots, gang wars and some population decline in the late 1960s. Street activists and minority groups such as the Black Panthers and Young Lords organized rent strikes and garbage offensives, demanding improved city services for poor areas. They also set up free health clinics and other programs, as a guide for organizing and gaining "Power to the People." By the 1970s the city had gained a reputation as a crime-ridden relic of history. In 1975, the city government avoided bankruptcy only through a federal loan and debt restructuring by the Municipal Assistance Corporation, headed by Felix Rohatyn. The city was also forced to accept increased financial scrutiny by an agency of New York State. In 1977, the city was struck by the twin crises of the New York City blackout of 1977 and serial slayings by the Son of Sam.

1978–present

|

The 1980s saw a rebirth of Wall Street, and the city reclaimed its role at the center of the worldwide financial industry. Unemployment and crime remained high, the latter reaching peak levels in some categories around the close of the decade and the beginning of the 1990s. Neighborhood restoration projects funded by the city and state had very good effects for New York, especially Bedford-Stuyvesant, Harlem, and The Bronx. The city later resumed its social and economic recovery, bolstered by the influx of Asians, Latin Americans, and U.S. citizens, and by new crimefighting techniques on the part of the NYPD. In the late 1990s, the city benefited from the success of the financial sectors, such as Silicon Alley, during the dot com boom, one of the factors in a decade of booming real estate values. New York was also able to attract more business, and convert abandoned industrialized neighborhoods into arts or attractive residential neighborhoods; examples include the Meatpacking District and Chelsea (in Manhattan) and Williamsburg (in Brooklyn). New York's population reached an all-time high in the 2000 census; according to census estimates since 2000, the city has continued to grow, including rapid growth in the most urbanized borough, Manhattan. During this period, New York City was also a site of the September 11 attacks of 2001; 2,606 people who were in the towers and in the surrounding area were killed by a terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, an event considered highly traumatic for the city but which did not stop the city's rapid regrowth. On November 3, 2014, One World Trade Center opened on the site of the attack.[43] Hurricane Sandy brought a destructive storm surge to New York City on the evening of October 29, 2012, flooding numerous streets, tunnels and subway lines in Lower Manhattan. It flooded low-lying areas of Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island. Electrical power was lost in many parts of the city and its suburbs.[44]

See also

|

Boroughs

Streets and thoroughfares |

Small islands |

Miscellany |

New York City portal

New York City portal

References

- ↑ "U.S. Bureau of the Census(1900–present)". Census.gov. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ↑ Rosenwaike, Ira (1972). Population History of New York City by Ira Rosenwaike (p.3 1656, through 1990). ISBN 978-0-8156-2155-3. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ↑ "City of New York: Population History - Highly Urbanized Boroughs(1790–2000)". Demographia.com. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ↑ Herbert C. Kraft, The Lenape: Archaeology, history, and ethnography (New Jersey Historical Society v 21, 1986)

- ↑ Foote, Thelma Wills (2004). Black and White Manhattan: The History of Racial Formation in Colonial New York. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-19-516537-3.

- ↑ Mark Kurlansky, The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, New York: Ballantine Books, 2006.

- 1 2 "Gotham Center for New York City History" Timeline 1700–1800

- ↑ Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1971). The European Discovery of America. Volume 1: The Northern Voyages. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. p. 490. ISBN 978-0195082715.

- ↑ Samuel Eliot Morison, The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages (1971). p. 490.

- 1 2 ""Battery Park". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved on September 13, 2008". Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ↑ Ellis, Edward Robb (1966). The Epic of New York City. Old Town Books. pp. 37–40.

- ↑ Ellis (1966), p. 57.

- ↑ Scheltema, Gajus and Westerhuijs, Heleen (eds.),Exploring Historic Dutch New York. Museum of the City of New York/Dover Publications, New York 2011.

- ↑ Homberger, Eric (2005). The Historical Atlas of New York City: A Visual Celebration of 400 Years of New York City's History. Owl Books. p. 34. ISBN 0-8050-7842-8.

- ↑ Harris, Leslie M. (2003). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. The University of Chicago Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0226317731.

- ↑ Harris, Leslie M. (2003). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. The University of Chicago Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0226317731.

- ↑ Spencer P.M. Harrington, "Bones and Bureaucrats", Archeology, March/April 1993, accessed 11 February 2012

- ↑ Rothstein, Edward (26 February 2010). "A Burial Ground and Its Dead Are Given Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ "The Hidden History of Slavery in New York". The Nation. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Exhibit: Slavery in New York". New York Historical Society. 7 October 2005 to 26 March 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-11. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Rothstein, Edward (26 February 2010). "A Burial Ground and Its Dead Are Given Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. p. 207. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

- ↑ Moore, Nathaniel Fish (1876). An Historical Sketch of Columbia College, in the City of New York, 1754–1876. Columbia College. p. 8.

- ↑ "The People's Vote: President George Washington's First Inaugural Speech (1789)". U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ↑ Bridges, William (1811). Map of the City of New York and Island of Manhattan with Explanatory Remarks and References.

- ↑ Lankevich (1998), pp. 67–68.

- ↑

- ↑ Bayor, Ronald H. (1997). The New York Irish. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-8018-5764-3.

- ↑ Lankevich (1998), pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Mushkat, Jerome Mushkat (1990). Fernando Wood: A Political Biography. Kent State University Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-87338-413-X.

- ↑ Cook, Adrian (1974). The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863. pp. 193–195.

- ↑ David R. Goldfield and Blaine A. Brownell, Urban America: A History(2nd ed. 1990), p 299

- ↑ The 100 Year Anniversary of the Consolidation of the 5 Boroughs into New York City, New York City. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ↑ Jackson, Kenneth (1995). Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 206. "[B]orough presidents ... responsible for local administration and public works."

- ↑ Robert A. Olmsted, "A History of Transportation in the Bronx", Bronx County Historical Society Journal (1989) 26#2 pp: 68–91

- ↑ Olmsted, Robert A. "Transportation Made the Bronx", Bronx County Historical Society Journal (1998) 35#2 pp: 166–180

- ↑ Gerometta, Marshall (2010). "Height: The History of Measuring Tall Buildings". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- ↑ City Mayors (2007-06-28). "The World's Largest Cities". Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ↑ Allen, Oliver E. (1993). "Chapter 9: The Decline". The Tiger – The Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- ↑ Charles Hagen (September 22, 1995). "Art in Review". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

In 1945... Todd Webb moved to New York City and began a remarkable project. For the next year Mr. Webb walked the streets of the city with a heavy camera and tripod, photographing the buildings and people he encountered...

- ↑ Burns, Ric (2003-08-22). "The Center of the World – New York: A Documentary Film (Transcript)". PBS. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

- ↑ http://skyscrapercenter.com/new-york-city/one-world-trade-center/98/

- ↑ Superstorm Sandy causes at least 9 U.S. deaths as it slams East Coast CNN

Further reading

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. New York, Chicago, Los Angeles: America's Global Cities (U of Minnesota Press, 1999), Compares the three cities in terms of geography, economics and race from 1800 to 1990

- Archdeacon, Thomas J. New York City, 1664–1710: Conquest and Change (1976)

- Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999), Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-195-11634-8, The standard scholarly history, 1390pp

- Burns, Ric, and James Sanders. New York: An Illustrated History (2003), book version of 17-hour Burns PBS documentary, "NEW YORK: A Documentary Film"

- Ellis, Edward Robb. The Epic of New York City: A Narrative History (2004) 640pp; Excerpt and text search; Popular history concentrating on violent events & scandals

- Homberger, Eric. The Historical Atlas of New York City: A Visual Celebration of 400 Years of New York City's History (2005)

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995), The Encyclopedia of New York City, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0300055366; second edition 2010

- Jackson, Kenneth T. and Roberts, Sam (eds.) The Almanac of New York City (2008)

- Jaffe, Steven H. New York at War: Four Centuries of Combat, Fear, and Intrigue in Gotham (2012) Excerpt and text search

- Kessner, Thomas. Fiorello H. LaGuardia and the Making of Modern New York (1989) the most detailed standard scholarly biography

- Kouwenhoven, John Atlee. The Columbia Historical Portrait of New York: An Essay In Graphic History. *1953)

- Lankevich, George J. New York City: A Short History (2002)

- McCully, Betsy. City At The Water's Edge: A Natural History of New York (2005), environmental history excerpt and text search

- Reitano, Joanne. The Restless City: A Short History of New York from Colonial Times to the Present (2010), Popular history with focus on politics and riots excerpt and text search

- Syrett, Harold Coffin. The city of Brooklyn, 1865-1898: a political history (Columbia University press, 1944)

Primary sources

- Burke, Katie. ed. Manhattan Memories: A Book of Postcards of Old New York (2000); Postcards lacking the (c) symbol are not copyright and are in the public domain.

- Jackson, Kenneth T. and David S. Dunbar, eds. Empire City: New York Through the Centuries 1015 pages of excerpts excerpt

- Still, Bayrd, ed. Mirror for Gotham: New York as Seen by Contemporaries from Dutch Days to the Present (New York University Press, 1956) online edition

- Virga, Vincent, ed. Historic Maps and Views of New York (2008)

- Stokes, I.N. Phelps. The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 compiled from original sources and illustrated by photo-intaglio reproductions of important maps plans views and documents in public and private collections (6 vols., 1915–28). A highly detailed, heavily illustrated chronology of Manhattan and New York City. see The Iconography of Manhattan Island All volumes are on line free at:

- I.N. Phelps Stokes; The Iconography of Manhattan Island Vol 1. 1915 v. 1. The period of discovery (1524-1609); the Dutch period (1609-1664). The English period (1664-1763). The Revolutionary period (1763-1783). Period of adjustment and reconstruction; New York as the state and federal capital (1783-1811)

- I.N. Phelps Stokes; The Iconography of Manhattan Island Vol 2. 1916 v. 2. Cartography: an essay on the development of knowledge regarding the geography of the east coast of North America; Manhattan Island and its environs on early maps and charts / by F.C. Wieder and I.N. Phelps Stokes. The Manatus maps. The Castello plan. The Dutch grants. Early New York newspapers (1725-1811). Plan of Manhattan Island in 1908

- I.N. Phelps Stokes; The Iconography of Manhattan Island Vol 3. 1918 v. 3. The War of 1812 (1812-1815). Period of invention, prosperity, and progress (1815-1841). Period of industrial and educational development (1842-1860). The Civil War (1861-1865); period of political and social development (1865-1876). The modern city and island (1876-1909)

- I.N. Phelps Stokes; The Iconography of Manhattan Island Vol 4. 1922; v. 4. The period of discovery (565-1626); the Dutch period (1626-1664). The English period (1664-1763). The Revolutionary period, part I (1763-1776)

- I.N. Phelps Stokes; The Iconography of Manhattan Island Vol 5. 1926; v. 5. The Revolutionary period, part II (1776-1783). Period of adjustment and reconstruction New York as the state and federal capital (1783-1811). The War of 1812 (1812-1815) ; period of invention, prosperity, and progress (1815-1841). Period of industrial and educational development (1842-1860). The Civil War (1861-1865) ; Period of political and social development (1865-1876). The modern city and island (1876-1909)

- I.N. Phelps Stokes; The Iconography of Manhattan Island Vol 6. 1928; v. 6. Chronology: addenda. Original grants and farms. Bibliography. Index.

Further viewing

- New York: A Documentary Film an eight part, 17½ hour documentary film directed by Ric Burns for PBS. It originally aired in 1999 with additional episodes airing in 2001 and 2003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of New York City. |

| Library resources about History of New York City |

- Columbia University Libraries. "New York City History". Research Guides. New York: Columbia University.

- New York University Libraries. "New York City". Research Guides. New York University.

- 'Historic Book Collection of New York on CD'

- Travel Guide to New York City Hotels and Tourism

- Gotham Center for New York City History

- Museum of the City of New York

- New-York Historical Society

- Interactive Timeline

- Origins of New York

- NYC Snapshot: Historic NYC

- A history of NYC by cosmopolis.ch

- The Mannahatta Project, seeking to map the Manhattan of 1609

- Historical photos of New York

- New York and its origins

- A Map and Timeline of many of the historical events mentioned in this article

- City map 1850

- Boston Public Library, Map Center. Maps of NYC, various dates

- "Urban Affairs". Research Guides. New York Public Library.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "New York (city)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "New York (city)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Select "New York City" value to browse NYC Maps (satyrical, political, pictorial) from 1883-1984 at the Persuasive Cartography, The PJ Mode Collection, Cornell University Library.