Hemoglobin E

| Hemoglobin E disease | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | D58.2 |

| DiseasesDB | 29719 |

| MeSH | D006446 |

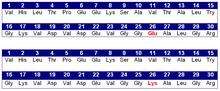

Hemoglobin E or haemoglobin E (HbE) is an abnormal hemoglobin with a single point mutation in the β chain. At position 26 there is a change in the amino acid, from glutamic acid to lysine. Hemoglobin E has been one of the less well known variants of normal hemoglobin. It is very common in Southeast Asia but has a low frequency amongst other ethnicities. HbE can be detected on electrophoresis.

The βE mutation affects β-gene expression creating an alternate splicing site in the mRNA at codons 25-27 of the β-globin gene. Through this mechanism, there is a mild deficiency in normal β mRNA and production of small amounts of anomalous β mRNA. The reduced synthesis of β chain may cause β-thalassemia. Also, this hemoglobin variant has a weak union between α- and β-globin, causing instability when there is a high amount of oxidant.[1]

Hemoglobin E disease (EE)

Hemoglobin E disease results when the offspring inherits the gene for HbE from both parents. At birth, babies homozygous for the hemoglobin E allele do not present symptoms due to HbF (fetal hemoglobin) they still have. In the first months of life, fetal hemoglobin disappears and the amount of hemoglobin E increases, so the subjects start to have a mild β-thalassemia. People who are heterozygote for hemoglobin E (one normal allele and one abnormal allele) do not show any symptoms (there is usually no anemia or hemolysis). There are cases associated with haemolysis.[2] Subjects homozygous for the hemoglobin E allele (two abnormal alleles) have a mild hemolytic anemia and mild enlargement of the spleen.

Hemoglobin E trait: heterozygotes for HbE (AE)

Heterozygous AE occurs when the gene for hemoglobin E is inherited from one parent and the gene for hemoglobin A from the other. This is called hemoglobin E trait, and it is not a disease. People who have hemoglobin E trait (heterozygous) are asymptomatic and their state does not usually result in health problems. They may have a low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and very abnormal red blood cells (target cells). Its clinical relevance is exclusively due to the potential for transmitting E or β-thalassemia.

Heterozygotes for HbE (SE)

Compound heterozygotes with hemoglobin sickle E disease result when the gene of hemoglobin E is inherited from one parent and the gene for hemoglobin S from the other. As the amount of fetal hemoglobin decreases and hemoglobin S increases, a mild hemolytic anemia appears in the early stage of development.

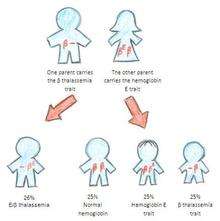

Hemoglobin E/β-thalassaemia

People who have hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia have inherited one gene for hemoglobin E from one parent and one gene for β-thalassemia from the other parent. Hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia is a severe disease, and it still has no universal cure. It affects more than a million people in the world.[3] The consequences of hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia when it is not treated can be heart failure, enlargement of the liver, problems in the bones, etc.

There is a variety of genotypes depending on the interaction of HbE and α-thalassemia. The presence of the α-thalassemia reduces the amount of HbE usually found in HbE heterozygotes. In other cases, in combination with certain thalassemia mutations, it provides an increased resistance to malaria (P. falciparum).[4]

Epidemiology

Hemoglobin E is most prevalent in Southeast Asia (Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam[5]), where its prevalence can reach 30 or 40%, and North-East India, where in certain areas carrier rates reach 60% of the population. In Thailand the mutation can reach 50 or 70%, and it is higher in the North-East of the country. It is also found in China, the Philippines, Turkey, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, etc. The mutation is estimated to have arisen within the last 5,000 years.[6] In Europe there have been found cases of families with hemoglobin E, but in these cases, the mutation differs from the one found in South-East Asia. This means that there may be different origins of the βE mutation.[7][8]

References

- ↑ Chernoff AI, Minnich V, Nanakorn S, et al. (1956). "Studies on hemoglobin E. I. The clinical, hematologic, and genetic characteristics of the hemoglobin E syndromes.". J Lab Clin Med. 47 (3): 455–489. PMID 13353880.

- ↑ A.V. Hoffbrand. Essential Haematology. Second edition. Page 69.

- ↑ Vichinsky E (2007). "Hemoglobin E Syndromes.". Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program: 79–83. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.79. PMID 18024613.

- ↑ Bachir, D; Galacteros, F (November 2004), Hemoglobin E disease. (PDF), Orphanet Encyclopedia, retrieved January 13, 2014

- ↑ Hemoglobin E Trait, University of Rochester Medical Center, retrieved January 13, 2014

- ↑ Ohashi; et al. (2004). "Extended linkage disequilibrium surrounding the hemoglobin E variant due to malarial selection". Am J Hum Genet. 74 (6): 1189–1208. doi:10.1086/421330. PMC 1182083

. PMID 15114532. Free full text

. PMID 15114532. Free full text - ↑ Kazazian HH, JR., Waber PG, Boehm CD, Lee JI, Antonarakis SE, Fairbanks VF. (1984). "Hemoglobin E in Europeans: Further Evidence for Multiple Origins of the βE-Globin Gene.". Am J Hum Genet. 36 (1): 212–217. PMC 1684388

. PMID 6198908. Free full text

. PMID 6198908. Free full text - ↑ Bain, Barbara J (June 2006). Blood cells: a practical guide (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-4265-6.

External links

- Hemoglobin E fact sheet from the Washington State Department of Health

- American Society of Hematology Educational Program profile of Hemoglobin E disorders

- Orphanet Encyclopedia entry for Hemoglobin E

- Hemoglobin E in Europeans