Colonization of Titan

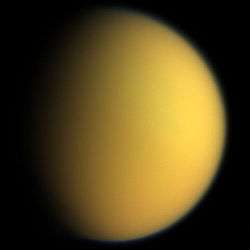

Saturn’s largest moon Titan is one of several candidates for possible future colonization of the outer Solar System.

Surface and atmospheric composition

According to Cassini data from 2008, Titan has hundreds of times more liquid hydrocarbons than all the known oil and natural gas reserves on Earth. These hydrocarbons rain from the sky and collect in vast deposits that form lakes and dunes.[1] "Titan is just covered in carbon-bearing material—it's a giant factory of organic chemicals", said Ralph Lorenz, who leads the study of Titan based on radar data from Cassini. "This vast carbon inventory is an important window into the geology and climate history of Titan." Several hundred lakes and seas have been observed, with several dozen estimated to contain more hydrocarbon liquid than Earth's oil and gas reserves. The dark dunes that run along the equator contain a volume of organics several hundred times larger than Earth's coal reserves.[2]

Radar images obtained on July 21, 2006 appear to show lakes of liquid hydrocarbon (such as methane and ethane) in Titan's northern latitudes. This is the first discovery of currently existing lakes beyond Earth.[3] The lakes range in size from about a kilometer in width to one hundred kilometers across.

On March 13, 2007, Jet Propulsion Laboratory announced that it found strong evidence of seas of methane and ethane in the northern hemisphere. At least one of these is larger than any of the Great Lakes in North America.[4]

Suitability

The American aerospace engineer and author Robert Zubrin identified Saturn as the most important and valuable of the four gas giants in the Solar System, because of its relative proximity, low radiation, and excellent system of moons. He also named Titan as the most important moon on which to establish a base to develop the resources of the Saturn system.[5]

Habitability

| Space colonization |

Dr. Robert Zubrin has pointed out that Titan possesses an abundance of all the elements necessary to support life, saying "In certain ways, Titan is the most hospitable extraterrestrial world within our solar system for human colonization." [6] The atmosphere contains plentiful nitrogen and methane, and strong evidence indicates that liquid methane exists on the surface. Evidence also indicates the presence of liquid water and ammonia under the surface, which are delivered to the surface by volcanic activity. Water can easily be used to generate breathable oxygen and nitrogen is ideal to add buffer gas partial pressure to breathable air (it forms about 78% of Earth's atmosphere).[7] Nitrogen, methane and ammonia can all be used to produce fertilizer for growing food.

Gravity

Titan has a surface gravity of 0.138 g, slightly less than that of the Moon. Managing long-term effects of low gravity on human health would therefore be a significant issue for long-term occupation of Titan, more so than on Mars. These effects are still an active field of study. They can include symptoms such as loss of bone density, loss of muscle density, and a weakened immune system. Astronauts in Earth orbit have remained in microgravity for up to a year or more at a time. Effective countermeasures for the negative effects of low gravity are well-established, particularly an aggressive regime of daily physical exercise or weighted clothing. The variation in the negative effects of low gravity as a function of different levels of low gravity are not known, since all research in this area is restricted to humans in zero gravity. The same goes for the potential effects of low gravity on fetal and pediatric development. It has been hypothesized that children born and raised in low gravity such as on Titan would not be well adapted for life under the higher gravity of Earth.[8]

Atmospheric conditions

The atmospheric pressure on Titan's surface is about one and a half times the pressure of Earth's atmosphere at sea level, making Titan the only celestial body in the Solar System besides Earth with a surface atmospheric pressure tolerable to humans. To put it into perspective, 1.5 atmospheres is approximately equivalent to the pressure experienced by a scuba diver on Earth at a water depth of only five meters, whereas the typical maximum recommended depth for recreational scuba divers is forty meters (equivalent to about five atmospheres of pressure). Matching the pressure of a habitat on Titan's surface to the ambient pressure would greatly reduce certain engineering difficulties. Titan's atmosphere is not toxic to humans, however the methane and hydrogen components are flammable in an oxygen atmosphere and would therefore need to be filtered out of buffer gas made from its atmosphere.

On the other hand, the temperature on Titan is about 94 K (−179 °C, or −290.2 °F), so insulation and heat generation and management would be significant concerns. However, because of the colder temperature the density of the air is closer to 4.5 times that of Earth sea level. At this density, temperature shifts over time and between one locale and another would be far smaller than comparable types of temperature changes present on Earth. The corresponding narrow range of temperature variation reduces the difficulties in structural engineering.

Relative thickness of the atmosphere combined with extreme cold makes additional troubles for human habitation. Unlike in a vacuum, the high atmospheric density makes thermoinsulation a significant engineering problem.

The engineering considerations for a spacesuit suitable for extravehicular activity on Titan's surface are radically different compared to a spacesuit designed for use in a vacuum. On the one hand, such a spacesuit would not need to be pressurized, but it would need to protect the wearer from the extreme cold, in addition to providing a breathable atmosphere. Compared to a vacuum, heat would rapidly dissipate in Titan's thick atmosphere. The degree of difficulty associated with working in such a spacesuit constructed with current technology would probably be at least equivalent to the difficulty associated with using a pressurized spacesuit in a vacuum.

Flight

The very high ratio of atmospheric density to surface gravity also greatly reduces the wingspan needed for an aircraft to maintain lift, so much so that a human would be able to strap on wings and easily fly through Titan's atmosphere while wearing a spacesuit that could be manufactured with current technology.[6] Another theoretically possible means to become airborne on Titan would be to use a hot air balloon-like vehicle filled with an Earth-like atmosphere at Earth-like temperatures (because oxygen is only slightly denser than nitrogen, the atmosphere in a habitat on Titan would be about one third as dense as the surrounding atmosphere), although such a vehicle would need a skin able to keep the extreme cold out in spite of the light weight required. Due to Titan's extremely low temperatures, heating of any flight-bound vehicle becomes a key obstacle.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Findings from the study led by Ralph Lorenz, Cassini radar team member from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, USA, are reported in the 29 January 2008 issue of the Geophysical Research Letters.

- ↑ "Titan's surface organics surpass oil reserves on Earth.". European Space Agency. 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "PIA08630: Lakes on Titan". Photojournal. NASA/JPL. 2006-07-24. Retrieved 2014-10-28.

- ↑ "Cassini Spacecraft Images Seas on Saturn's Moon Titan". Cassini Solstice Mission. NASA/JPL. 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2014-10-28.

- ↑ Robert Zubrin, Entering Space: Creating a Spacefaring Civilization, section: The Persian Gulf of the solar system, pp. 161-163, Tarcher/Putnam, 1999, ISBN 978-1-58542-036-0

- 1 2 Robert Zubrin, Entering Space: Creating a Spacefaring Civilization, section: Titan, pp. 163-166, Tarcher/Putnam, 1999, ISBN 978-1-58542-036-0

- ↑ Robert Zubrin, The Case for Mars: The Plan to Settle the Red Planet and Why We Must, p. 146, Simon & Schuster/Touchstone, 1996, ISBN 978-0-684-83550-1

- ↑ Robert Zubrin, "Colonizing the Outer Solar System", in Islands in the Sky: Bold New Ideas for Colonizing Space, pp. 85-94, Stanley Schmidt and Robert Zubrin, eds., Wiley, 1996, ISBN 978-0-471-13561-6

- ↑ Randall Munroe (2013). "Interplanetary Cessna". Retrieved 2013-01-29.

Further reading

- Stephen L. Gillett, "Titan as the Abode of Life," Analog, Vol. CXII No. 13, pp. 40–55 (1992)

- Julian Nott - Titan: A Distant But Enticing Destination for Human Visitors (White Paper for National Academy of Sciences]

- Charles Wohlforth; Amanda R. Hendrix Ph.D. (2016). Beyond Earth: Our Path to a New Home in the Planets. ISBN 978-0804197977.