Hijab by country

The word hijab refers to both the head-covering traditionally worn by some Muslim women and modest Islamic styles of dress in general.

The garment has different legal and cultural statuses in various countries. There are a few countries which have banned the wearing of all overt religious symbols, including the hijab (a Muslim headscarf, literally Arabic "to cover"), in public schools and universities or government buildings.

Kosovo (since 2009),[1] Azerbaijan (since 2010[2]), Tunisia (since 1981,[3] partially lifted in 2011) and Turkey (since 1997,[4] de facto partially lifted in 2013) are the only Muslim-majority countries which have banned the hijab in public schools and universities or government buildings, while Syria banned face veils in universities from July 2010.[5] In other Muslim states such as Morocco,[6] there has been some restriction or discrimination against women who wear the hijab. The hijab in these cases is seen as a sign of political Islam or fundamentalism against secular government.

In the southern communities of Iraq, especially in Najaf and Karbala, hijab is compulsory. In public places, women there usually wear the abaya, which is a long black cloth that covers the whole body except the face and the hands, in addition to the scarf that only covers the head. However, in private, in governmental institutions and universities, they can wear manteaux which can be long or short and a scarf. In Baghdad and the northern communities, women have more freedom to wear what they feel comfortable with.

Islamic dress, notably the variety of headdresses worn by Muslim women, has become a prominent symbol of the presence of Islam in western Europe. In several countries this adherence to hijab has led to political controversies and proposals for a legal ban. The Dutch parliament has decided to introduce a ban on face-covering clothing, popularly described as the "burqa ban", although it does not only apply to the Afghan-model burqa. Similar laws have been passed in France and Belgium.

Other countries are debating similar legislation, or have more limited prohibitions. Some of them apply only to face-covering clothing such as the burqa, boushiya, or niqāb, while other legislation pertains to any clothing with an Islamic religious symbolism such as the khimar, a type of headscarf. (Some countries already have laws banning the wearing of masks in public, which can be applied to veils that conceal the face). The issue has different names in different countries, and "the veil" or "hijab" may be used as general terms for the debate, representing more than just the veil itself, or the concept of modesty embodied in hijab.

Although the Balkans and Eastern Europe have indigenous Muslim populations, most Muslims in western Europe are members of immigrant communities. The issue of Islamic dress is linked with issues of immigration and the position of Islam in Western Europe.

Europe

European Commissioner Franco Frattini said in November 2006, that he did not favour a ban on the burqa.[7] This is apparently the first official statement on the issue of prohibition of Islamic dress from the European Commission, the executive of the European Union.

When Nobel Peace Laureate Tawakkul Karman was asked about her hijab by journalists and how it is not proportionate with her level of intellect and education, she replied, "Man in early times was almost naked, and as his intellect evolved he started wearing clothes. What I am today and what I’m wearing represents the highest level of thought and civilization that man has achieved, and is not regressive. It’s the removal of clothes again that is regressive back to ancient times."[8] Islamic dress is also seen as a symbol of the existence of parallel societies, and the failure of integration: in 2006 British Prime Minister Tony Blair described the face veil as a "mark of separation".[9] Proposals to ban hijab may be linked to other related cultural prohibitions: the Dutch politician Geert Wilders proposed a ban on hijab, on Islamic schools, on new mosques, and on non-western immigration.

In France and Turkey, the emphasis is on the secular nature of the state, and the symbolic nature of the Islamic dress. In Turkey, bans apply at state institutions (courts, civil service) and in state-funded education. In 2004, France passed a law banning "symbols or clothes through which students conspicuously display their religious affiliation" (including hijab) in public primary schools, middle schools, and secondary schools,[10] but this law does not concern universities (in French universities, applicable legislation grants students freedom of expression as long as public order is preserved[11]). These bans also cover Islamic headscarves, which in some other countries are seen as less controversial, although law court staff in the Netherlands are also forbidden to wear Islamic headscarves on grounds of 'state neutrality'.

An apparently less politicised argument is that in specific professions (teaching), a ban on "veils" (niqab) is justified, since face-to-face communication and eye-contact is required. This argument has featured prominently in judgments in Britain and the Netherlands, after students or teachers were banned from wearing face-covering clothing.

Public and political response to such prohibition proposals is complex, since by definition they mean that the government decides on individual clothing. Some non-Muslims, who would not be affected by a ban, see it as an issue of civil liberties, as a slippery slope leading to further restrictions on private life. A public opinion poll in London showed that 75 percent of Londoners support "the right of all persons to dress in accordance with their religious beliefs".[12] In another poll in the United Kingdom by Ipsos MORI, 61 percent agreed that "Muslim women are segregating themselves" by wearing a veil, yet 77 percent thought they should have the right to wear it.[13] In a later FT-Harris poll conducted in 2010 after the French ban on face-covering went into effect, an overwhelming majority in Italy, Spain, Germany and the UK supported passing such bans in their own countries.[14] The headscarf is perceived to be a symbol of the clash of civilizations by many. Others would also argue that the increase of laws surrounding the banning of headscarves and other religious paraphernalia has led to an increase in not just the sales of headscarves and niqabs, but an increase in the current religiosity of the Muslim population in Europe: as both a product of and a reaction to westernization.[15]

Currently, France, Belgium and the Netherlands are three European countries with specific bans on face-covering dress, such as the Islamic niqab or burqa.[16] Since the bans took effect, there have been several instances of Muslims perpetrating violence and acts of vandalism in apparently coordinated protests, often aimed at police officers enforcing the laws.[17]

The French law against covering the face in public, known as the "Burqa ban", was challenged and taken to the European Court of Human Rights which upheld the law on 1 July 2014, accepting the argument of the French government that the law was based on "a certain idea of living together".[18]

European countries of Switzerland, Italy and Spain have banned Burqa and Niqab in specific cities. Ticino in Switzerland, Lombardy in Italy and Reus in Spain have imposed the burqa ban.[19] Bulgaria banned wearing burqas in public from 30 September 2016.

Muslim world

Afghanistan

The Afghan chadri is a regional style of burqa with a mesh covering the eyes.[20] It has been worn by Pashtun women since pre-Islamic times and was historically seen as a mark of respectability.[20] Under the Taliban, the burqa was obligatory.[21] While this is officially no longer the case, some women continue to wear it out of security concerns or as a cultural practice.[22][23][20]

Bangladesh

There are no laws that require women to cover their heads. The ghumta, commonly worn by elderly women in rural and urban areas, is a loose hair-covering using the achal of the saree. Since 9/11 the hijab veil, separate from the saree, has been introduced and worn by some women in urban areas.

Chad

Following a double suicide on June 15, 2015 with 33 people dead in N'Djamena, the Chadian government announced June 17, 2015 banning the wearing of the burqa in its territory for security reasons[24][25]

Egypt

In 1923, Hoda Shaarawi made history when, while waiting for the press, she removed her veil in a symbolic act of liberation. The veil gradually disappeared in the following decades, so much so that by 1958 an article by the United Press (UP) stated that "the veil is unknown here."[26] However, the veil has been having a resurgence since the 1970s, concomitant with the global revival of Muslim piety. According to The New York Times, as of 2007 about 90 percent of Egyptian women currently wear a headscarf.[27]

Small numbers of women wear the niqab. The secular government does not encourage women to wear it, fearing it will present an Islamic extremist political opposition. In the country, it is negatively associated with Salafist political activism.[28][29] There has been some restrictions on wearing the hijab by the government, which views hijab as a political symbol. In 2002, two presenters were excluded from a state run TV station for deciding to wear hijab on national television.[30] The American University in Cairo, Cairo University and Helwan University attempted to forbid entry to niqab wearers in 2004 and 2007.[31][32][33]

Mohammad Tantawi, a leading Islamic scholar in the country and the head of Al-Azhar University, issued a fatwa in October 2009 arguing that veiling of the face is not required under Islam. He had reportedly asked a student to take off her niqab when he spotted her in a classroom, and he told her that the niqab is a cultural tradition without Islamic importance.[28] It is widely believed that the hijab is becoming more of a fashion statement than a religious one in Egypt, with many Egyptian women, influenced by social peer pressure, wearing colorful, stylish head scarves along with western style clothing. Government bans on wearing the niqab on college campuses at the University of Cairo and during university exams in 2009 were overturned later.[34][35][36][37] Minister Hany Mahfouz Helal met protests by some human rights and Islamist groups.

In 2010, Baher Ibrahim of The Guardian criticized the increasing trend for pre-pubescent girls in Egypt to wear the hijab.[38]

Many Egyptians in the elite are opposed to hijab, believing it harms secularism. By 2012 some businesses had established bans on veils, and Egyptian elites supported these bans.[39]

The Gambia

In the Gambia, only a small minority of women wear the hijab. The Gambia is an Islamic country but does not enforce the wearing of the hijab.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the term jilbab is used without exception to refer to the hijab.[40] Under Indonesian national and regional law, female head-covering is entirely optional and not obligatory.

The hijab is a relatively new phenomenon in Indonesia. Even before Western influence, most Indonesian women (especially Javanese) rarely covered their hair except when praying, and even then the hair was only loosely covered by a transparent cloth.

In 2008, Indonesia had the single largest global population of Muslims. However, the Indonesian Constitution of Pancasila provides equal government protection for five state-sanctioned religions (namely Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Buddhism and Hinduism), without any one supreme or official state religion.

Some women may choose to wear a headscarf to be more "formal" or "religious", such as the jilbab or kerudung (a native tailored veil with a small, stiff visor). Such formal or cultural Muslim events may include official governmental events, funerals, circumcision (sunatan) ceremonies or weddings. However, wearing Islamic attire to Christian relatives' funerals and weddings and entering the church is quite uncommon.

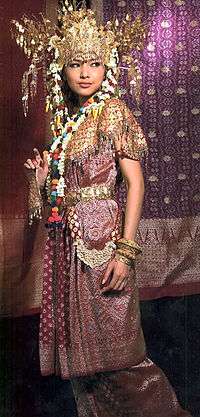

Culturally to the Javanese majority, plain, Saudi-style hijab, the niqab or socially worse yet the indigenous peasant kerudung (known in North Sumatran languages as tudung) is considered vulgar, low-class and a faux pas – the traditional Javanese hijab are transparent, sheer, intricately brocaded or embroidered fine silk or lace tailored to match either their sarung or kebaya blouse.

Young girls may also elect to wear the hijab publicly to avoid unwanted low-class male attention and molestation and thus display their respectability as "good Muslim girls": that is, they are not "easy" conquests.[41] Additionally, Islamic private school uniform code dictate that female students must wear the jilbab (commonly white or blue-grey, Indonesia's national secondary school colours), in addition to long-sleeved blouse and ankle-length skirt. While Islamic schools must by law provide access to Christians (and vice versa Catholic and Protestant schools allow Muslim students) it is worn without complaint by Christian students and its use is not objected to in Christian schools, as nuns in Indonesia also wear habits.

Many nuns refer to their habit as a jilbab, perhaps out of the colloquial use of the term to refer to any religious head covering.

The sole exception where jilbab is mandatory is in Aceh Province, under Islamic Sharia-based Law No 18/2001, granting Aceh special autonomy and through its own Regional Legislative body Regulation Nr. 5/2001, as enacted per Acehnese plebiscite (in favour). This Acehnese Hukum Syariah and the reputedly over-bearing "Morality Police" who enforce its (Aceh-only) mandatory public wearing are the subject of fierce debate, especially with regards to its validity vis-a-vis the Constitution among Acehnese male and female Muslim academics, Acehnese male and female politicians and female rights advocates.

Female police officers are not allowed to wear hijab, except in Aceh. But since March 25, 2015, based on Surat Keputusan Kapolri Nomor:Kep/245/II/2015 female police officers can now wear hijab if they want. Flight attendants are not allowed to wear hijab except during flights to the Middle East.

Compounding the friction and often anger toward baju Arab (Arab clothes), is the ongoing physical and emotional abuse of Indonesian women in Saudi Arabia, as guest workers, commonly maids or as Hajja pilgrims and Saudi Wahhabi intolerance for non-Saudi dress code has given rise to mass protests and fierce Indonesian debate up to the highest levels of government about boycotting Saudi Arabia – especially the profitable all Hajj pilgrimage – as many high-status women have been physically assaulted by Saudi morality police for non-conforming head-wear or even applying lip-balm – leading some to comment on the post-pan Arabist repressiveness of certain Arab nations due to excessively rigid, narrow and erroneous interpretation of Sharia law.[42][43]

Iran

In Iran, women are required to wear loose-fitting clothing and a headscarf in public.[44][45]

For many centuries, since ancient pre-Islamic times, female headscarf was a normative dress code in the Greater Iran. First veils in region are historically attested in ancient Mesopotamia as a complementary garment,[46] but later it became exclusionary and privileging in Assyria, even regulated by social law. Veil was a status symbol enjoyed by upper-class and royal women, while law prohibited peasant women, slaves and prostitutes from wearing the veil, and violators were punished.[46][47] After ancient Iranians conquered Assyrian Nineveh in 612 BC and Chaldean Babylon in 539 BC, their ruling elite has adopted those Mesopotamian customs.[46] During the reign of ancient Iranian dynasties, veil was first exclusive to the wealthy, but gradually the practice spread and it became standard for modesty.[48] Later, after the Muslim Arabs conquered Sassanid Iran, early Muslims adopted veiling as a result of their exposure to the strong Iranian cultural influence.[47][48][49][50][51]

This general situation did change somewhat in the Middle Ages after arrival of the Turkic nomadic tribes from Central Asia, whose women didn’t wear headscarves.[51][52] However, after the Safavid centralization in the 16th century, the headscarf became defined as the standard head dress for the women in urban areas all around the Iranian Empire.[53] Exceptions to this standard were seen only in the villages and among the nomads, so women without a headscarf could be found only among rural people and nomadic tribes[51][52][54][55][56] (like Qashqai). Veiling of faces, that is, covering the hair and the whole face was very rare among the Iranians and was mostly restricted to the Arabs and the Afghans. Later, during the economic crisis in the late 19th century under the Qajar dynasty, the poorest urban women could not afford headscarves due to the high price of textile and its scarcity.[54] Owing to the aforementioned historical circumstances, the covering of hair has always been the norm in Iranian dress, and removing it was considered impolite, or even an insult.[45] In the early 20th century, the Iranians associated not wearing it as something rural, nomadic, poor and non-Iranian. Since Iran, unlike most of its neighbors, was never colonized by any of the European powers, the Western influences and foreign dress code didn't prevail.

Attempts at changing the dress code (and perspectives toward it) occurred in mid-1930s when pro-Western autocratic ruler Reza Shah issued an arbitrary decree, banning all veils abruptly, swiftly and forcefully.[47][45][57][58][59] Many types of male traditional clothing were also banned under the pretext that "Westerners now wouldln’t laugh at us".[60][61][62] Western historians state that this would have been a progressive step if women had indeed chosen to do it themselves, but instead this ban humiliated and alienated many Iranian women,[46][51][55][57] since its effect was comparable to the hypothetical situation in which the European women had suddenly been ordered to go out topless into the street.[46][60][61][62] To enforce this decree, the police was ordered to physically remove the veil off of any woman who wore it in public. Women were beaten, their headscarves and chadors torn off, and their homes forcibly searched.[46][47][55][45][57][60][61][62][63][64] Until Reza Shah’s abdication in 1941, many women simply chose not leave their houses in order to avoid such embarrassing confrontations,[47][55][60][61][62] and few even committed suicide.[60][61][62] A far larger escalation of violence occurred in the summer of 1935 when Reza Shah ordered all men to wear European-style bowler hat, which was Western par excellence. This provoked massive non-violent demonstrations in July in the city of Mashhad, which were brutally suppressed by the army, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 100 to 5,000 people (including women and children).[55][45][58][60][61][62][64] Historians often point that Reza Shah’s ban on veiling and his policies (known as kashf-e hijab campaign) are unseen even in Atatürk’s Turkey,[46][55] and some scholars state that it is very difficult to imagine that even Hitler’s or Stalin’s regime would do something similar.[60][61][62] The arbitrary decree by Reza Shah was criticized even by British consul in Tehran.[65] Later, official measures relaxed slightly under next ruler and wearing of the headscarf or chador was no longer an offence, but for his regime it became a significant hindrance to climbing the social ladder as it was considered a badge of backwardness and an indicator of being a member of the lower class.[46] Discrimination against the women wearing the headscarf or chador was still widespread with public institutions actively discouraging their use, and some eating establishments refusing to admit women who wore them.[47][66] This period is characterized by dichotomy between small minority who considered wearing of headscarf as a sign of backwardness and vast majority who considered it as progressive.[45][57][59] Despite all legal pressures, obstacles and discriminations, the largest proportion of the Iranian women continued to wear headscarves or chadors, contrary to the widespread opposite claims.[47][55][60][61][62][65][66]

A few years prior to the Iranian revolution, a tendency towards questioning the relevance of Eurocentric gender roles as the model for Iranian society gained much ground among university students, and this sentiment was manifested in street demonstrations where many women from the non-veiled middle classes put on the veil[46][47][45][67][44] and symbolically rejected the gender ideology of Pahlavi regime and its aggressive deculturalization.[46][47][45][57][44] Many argued that veiling should be restored to stop further dissolution of the Iranian identity and culture,[45] as from an Iranian point of view the unveiled women are seen as exploited by Western materialism and consumerism.[51][56][45][57] Wearing of headscarf and chador was one of main symbols of the revolution,[45][57][66][44] along with the resurgence and wearing of other traditional Iranian dresses. Headscarves and chadors were worn by all women as a religious and/or nationalistic symbols,[45][57][66][44] and even many secular and Westernized women, who did not believe in wearing them before the revolution, began wearing them, in solidarity with the vast majority of women who always wore them.[46][47][45][67][44] Wearing headscarves and chadors was used as a significant populist tool and Iranian veiled women played an important rule in the revolution’s victory.[46][57][59]

In the aftermath of the revolution, hijab was made compulsory in stages.[45] In 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini announced that women should observe Islamic dress code.[45][68] His statement sparked demonstrations organized by an alliance of Westernized women and leftists, which were met by government's assurances that the statement was only a recommendation.[45][68] Hijab was subsequently made mandatory in government and public offices in 1980, which evoked only disorganized reactions, and in 1983 it became mandatory for all women.[45] Veillessless had become associated with cultural imperialism and many Iranians advocated compliance with compulsory veiling in the name national independence, rejection of corrupt royalists, and avoiding distraction from what they saw as more pressing issues.[45]

Over the years, post-revolutionary Iranian women’s fashion gradually evolved from the monotonous chador to its present form, where a simple headscarf (rousari) combined with other colorful elements of clothing has become more predominant.[51][64] In 2010, 531 young women (aged 15–29) from different cities in nine provinces of Iran participated in a study the results of which showed that 77% prefer stricter covering, 19% loose covering, and only 4% don’t believe in veiling at all.[69] A tendency towards Western dress correlated with 66% of the latest non-compliance with the dress-code.[69]

Jordan

There are no laws requiring the wearing of headscarves nor any banning such from any public institution. The use of the headscarf increased during the 1980s. However, the use of the headscarf is generally prevalent among the lower and lower middle classes. Veils covering the face as well as the chador are rare. It is widely believed that the hijab is increasingly becoming more of a fashion statement in Jordan than a religious one with Jordanian women wearing colorful, stylish headscarves along with western-style clothing.[70]

Kosovo

Since 2009, the hijab was banned in public schools and universities or government buildings.[71] In 2014, the first female parliamentarian with hijab was elected to the Kosovar parliament.[72]

Lebanon

The wearing of headscarves has become more common since the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in the 1980s. Observance of this custom ranges from no headscarf at all to just a regular hijab and a chador.[29]

Malaysia

The headscarf is known as a tudung, which simply means "cover". (The word is used with that meaning in other contexts, e.g. tudung saji, a dish cover for food.) Muslim women may freely choose whether or not to wear the headscarf. The exception is when visiting a mosque, where the tudung must be worn; this requirement also includes non-Muslims.

Although headscarves are permitted in government institutions, public servants are prohibited from wearing the full-facial veil or niqab. A judgment from the then–Supreme Court of Malaysia cites that the niqab, or purdah, "has nothing to do with (a woman's) constitutional right to profess and practise her Muslim religion", because Islam does not make it obligatory to cover the face.[73]

Although wearing the hijab, or tudung, is not mandatory for women in Malaysia, some government buildings enforce within their premises a dresscode which bans women, Muslim and non-Muslim, from entering while wearing "revealing clothes".[74][75]

As of 2013 most Muslim Malaysian women wear the tudung, a type of hijab. This use of the tudung was uncommon prior to the 1979 Iranian revolution,[76] and the places that had women in tudung tended to be rural areas. The usage of the tudung sharply increased after the 1970s.[75] as religious conservatism among Malay people in both Malaysia and Singapore increased.[77]

Several members of the Kelantan ulama in the 1960s believed the hijab was not mandatory.[76] By 2015 the Malaysian ulama believed this previous viewpoint was un-Islamic.[78]

By 2015 Malaysia had a fashion industry related to the tudung.[76]

Morocco

The headscarf is not encouraged by governmental institutions, and generally frowned upon by urban middle and higher classes but it is not forbidden by law. The headscarf is becoming gradually more frequent in the north, but as it is not traditional, to wear one is considered rather a religious or political decision. In 2005, a schoolbook for basic religious education was heavily criticized for picturing female children with headscarves, and later the picture of the little girl with the Islamic headscarf was removed from the school books.[79] The headscarf is strongly and implicitly forbidden in Morocco's military and the police.

Pakistan

Pakistan has no laws banning or enforcing the ħijāb.

In Pakistan, most women wear the shalwar kameez, a tunic top and baggy trouser set which covers their arms, legs and body. A loose dupatta scarf is worn around the shoulders, upper chest and head since showing one's hair is considered rude and in bad taste. Men also have a similar dress code, but only women are expected to wear a veil in public.[80][81] Many women in Pakistan wear other forms of the ħijāb but it varies in design; for example in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas most of the women wear the full head-to-toe black burqa/chador while in the rest of the provinces, including Azad Kashmir, most of the women wear the dupatta (a long scarf that matches the woman's garments). The ħijāb together with a duppatta is becoming unpopular among the younger generation. Burqas are mainly worn in the Swat Valley and Islamist zones, however, they can be seen throughout the country including in urban population centers.

Westerners are also expected to dress modestly too. Pakistani society observes traditional dress customs and it is advisable for women to wear long skirts, baggy trousers and long-sleeved tops or wear the traditional shalwar kameez in public. In the big cities, some women wear jeans and khakis, especially in casual settings, shopping malls and around picnic spots. Dress codes for men are more lax, though shorts are uncommon. Vest tops, bikinis and mini-skirts in public are considered immodest and are thus a social taboo.[80][81]

Saudi Arabia

According to most Saudi Salafi scholars, a woman's awrah in front of unrelated men is her entire body including her face and hands. Hence, the vast majority of traditional Saudi women are expected to cover their faces in public.[82][83][84][85][86]

The Saudi niqāb usually leaves a long open slot for the eyes; the slot is held together by a string or narrow strip of cloth.[87] Many also have two or more sheer layers attached to the upper band, which can be worn flipped down to cover the eyes. Although a person looking at a woman wearing a niqab with an eye-veil would not be able to see her eyes, she is able to see out through the thin fabric.

Many Saudi women use a headscarf along with the niqab or another simple veil to cover all or most of the face when in public, as do most foreign Muslim women (i.e., those from other Arab states, South Asia, Indonesia, or European converts to Islam). But there are many Muslim women, including Saudis, who only wear a headscarf without the niqab, similarly to most non-Muslim women who use only a headscarf or no face covering at all.

Somalia

During regular, day-to-day activities, Somali women usually wear the guntiino, a long stretch of cloth tied over the shoulder and draped around the waist. In more formal settings such as weddings or religious celebrations like Eid, women wear the dirac, which is a long, light, diaphanous voile dress made of cotton or polyester that is worn over a full-length half-slip and a brassiere. Married women tend to sport head-scarves referred to as shash, and also often cover their upper body with a shawl known as garbasaar. Unmarried or young women, however, do not always cover their heads. Traditional Arabian garb such as the hijab and the jilbab is also commonly worn.[88]

Sudan

In accordance with the nation's Constitution, Sudanese women are required to wear the hijab while in public at all times. Non-wearing of the hijab, which is considered to be immoral, is implicitly forbidden by Sudanese law, stating: “Whoever does in a public place an indecent act or an act contrary to public morals or wears an obscene outfit or contrary to public morals or causing an annoyance to public feelings shall be punished with flogging which may not exceed forty lashes or with fine or with both.”[89] In 2013, the case of Amira Osman Hamid came to international attention when she chose to expose her hair in public, in opposition to the nation's public-order laws.[90]

Syria

In 2010, Ghiyath Barakat, Syria's minister of higher education, announced that the government would ban women from wearing full-face veils at universities. Among the prohibited garments would be the niqab, but not the hijab or related garments that do not cover the entire face. The official stated that the face veils ran counter to secular and academic principles of Syria.[91]

Tunisia

Tunisian authorities say they are encouraging women, instead, to "wear modest dress in line with Tunisian traditions", i.e. no headscarf. In 1981, women with headscarves were banned from schools and government buildings, and since then those who insist on wearing them face losing their jobs.[3] Recently in 2006, the authorities launched a campaign against the hijab, banning it in some public places, where police would stop women on the streets and ask them to remove it, and warn them not to wear it again. The government described the headscarf as a sectarian form of dress which came uninvited to the country.[92]

As of 14 January 2011, after the Tunisian revolution took place,[93] the headscarf was authorized and the ban lifted.

Turkey

Turkey is officially a secular state, and the hijab was banned in universities and public buildings until late 2013 – this included libraries or government buildings. The ban was first in place during the 1980 military coup, but the law was strengthened in 1997.[94] Over the years thousands of women have been arrested or prosecuted for refusing to take off the hijab or protesting against the ban by the secular state.[95] There has been some unofficial relaxation of the ban under governments led by the conservative party AKP in recent years,[29] for example the current government of the AKP is willing to lift the ban in universities, however the new law was upheld by the constitutional court. The ban has been highly controversial since its implementation in a country where 99% are either practising or nominal Muslims or assumed as Muslim by the state.

Some researchers claim that just about 35% of Turkish women cover their heads; even though that is a low number for a mostly Muslim country. Many women wear a headscarf for cultural reasons that is not a symbol of the Quran. That cultural headscarf is used by women that work under the sun to protect their heads from sunburn.[96] This is often misinterpreted by some, who instead assume that the headscarf in Turkish research only represents the hijab and not the cultural derivation, and this is probably why many think that a majority of Turkish women wear Islamic covering. Researches also show that the usage of the hijab has declined since the 1990s. In cities like Istanbul and Ankara most women do not cover their heads.[97] In some cities in eastern Turkey where a conservative mentality still is more dominant, more women cover their heads .[94][98][99]

On 7 February 2008, the Turkish Parliament passed an amendment to the constitution, allowing women to wear the headscarf in Turkish universities, arguing that many women would not seek an education if they could not wear the hijab.[100][101][102][103] The decision was met with powerful opposition and protests from secularists. On 5 June 2008, the Constitutional Court of Turkey reinstated the ban on constitutional grounds of the secularity of the state.[104] Headscarves had become a focal point of the conflict between the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the secularist establishment, which includes the courts, universities, and army. The ruling was widely seen as a victory for Turks who claim this maintains Turkey's separation of state and religion. In 2013, the headscarf ban in public institutions was lifted through a decree, even though the ban officially stands through court decisions.[105]

Greater Middle East

Cyprus

Traditionally in Cyprus Orthodox Christian Greek women wore the mandili (a white headscarf) for practical reasons when working in the fields for protection from the heat.[106] Some Greek women wore very large white outer garments when travelling in exposed sun, as the colour absorbed less heat and the size provided shade.[107] Black headscarves are still often worn by women as a symbol of mourning.

The mandili also features prominently in Greek marriage rituals where it is used to represent the inheritance of the families' bond.[108]

Iraq

In southern communities of Iraq especially in Najaf and Karbala, hijab is compulsory. Women in public places usually wear abaya which is a long black cloth that covers the whole body except the face and the hands, in addition to the scarf that only covers the hair. They might wear boushiya. In private, in governmental institutions and universities they can wear manteaux which could be long or short with a scarf covering the head. In Baghdad and the northern communities, women there have more freedom to wear what they feel comfortable with.

Israel

In July 2010, some Israeli lawmakers and women's rights activists proposed a bill to the Knesset banning face-covering veils. According to the Jerusalem Post, the measure is generally "regarded as highly unlikely to become law." Hanna Kehat, founder of the Jewish women’s rights group Kolech, criticized a ban and also commented "[f]ashion also often oppresses women with norms which lead to anorexia." Eilat Maoz, general coordinator for the Coalition of Women for Peace, referred to a ban as "a joke" that would constitute "racism".[109] In Israel, orthodox Jews dress modestly by keeping most of their skin covered. Married women cover their hair, most commonly in the form of a scarf, also in the form of hats, snoods, berets, or, sometimes, wigs.[110][111]

Gaza Strip

Successful informal coercion of women by sectors of society to wear Islamic dress or hijab has been reported in the Gaza Strip where Mujama' al-Islami, the predecessor of Hamas, reportedly used a mixture of consent and coercion to "'restore' hijab" on urban-educated women in Gaza in the late 1970s and 1980s.[112] Similar behavior was displayed by Hamas during the first intifada.[113] Hamas campaigned for the wearing of the hijab alongside other measures, including insisting that women stay at home, they should be segregated from men, and for the promotion of polygamy. During the course of this campaign women who chose not to wear the hijab were verbally and physically harassed, with the result that the hijab was being worn "just to avoid problems on the streets".[114]

Following the takeover of the Gaza Strip in June 2007, Hamas has attempted to implement Islamic law in the Gaza Strip, mainly at schools, institutions and courts by imposing the Islamic dress or hijab on women.[115]

Some of the Islamization efforts met resistance. When Palestinian Supreme Court Justice Abdel Raouf Al-Halabi ordered women lawyers to wear headscarves and caftans in court, attorneys contacted satellite television stations including Al-Arabiya to protest, causing Hamas’s Justice Ministry to cancel the directive.[116]

In 2007, the Islamic group Swords of Truth threatened to behead female TV broadcasters if they didn't wear the hijab. "We will cut throats, and from vein to vein, if needed to protect the spirit and moral of this nation," their statement said. The group also accused the women broadcasters of being "without any ... shame or morals". Personal threats against female broadcasters were also sent to the women's mobile phones, though it was not clear if these threats were from the same group. Gazan anchorwomen interviewed by Associated Press said that they were frightened by the Swords of Truth statement.[117]

In February 2011, Hamas banned the styling of women's hair, continuing its policy of enforcing Sharia upon women's clothing.[118]

Hamas has imposed analogous restrictions on men as well as women. For example, men are no longer allowed to be shirtless in public.[118]

Northern Cyprus

Muslim Turkish-Cypriot women wore traditional Islamic headscarves.[106] When leaving their homes, Muslim Cypriot women would cover their faces by pulling a corner of the headscarf across their nose and mouth, a custom recorded as early as 1769:[119]

Their head dress...consists of a collection of various handkerchiefs of muslim, prettily shaped, so that they form a kind of casque of a palm's height, with a pendant behind to the end of which they attach another handkerchief folded in a triangle, and allowed to hang on their shoulders. When they go out of doors modesty requires that they should take a corner and pull it in front to cover the chin, mouth and nose. The greater part of the hair remains under the ornaments mentioned above, except on the forehead where it is divided into two locks, which are led along the temples to the ears, and the ends are allowed to hang loose behind over the shoulders.— Giovanni Mariti, Travels in the Island of Cyprus, 1769

In accordance with the islands' strict moral code, Turkish Cypriot women also wore long skirts or pantaloons in order to cover the soles of their feet. Most men covered their heads with either a headscarf (similar to a wrapped keffiyeh, "a form of turban"[120]) or a fez. Turbans have been worn by Cypriot men since ancient times and were recorded by Herodotus, during the Persian rule of the island, to demonstrate their "oriental" customs compared to Greeks.[121]

Following the globalisation of the island, however, many younger Sunni Muslim Turkish-Cypriots abandoned wearing traditional dress, such as headscarves.[122] Yet they are still worn by older Muslim Cypriot women.

Until the removal of ban on headscarf in universities in Turkey in 2008,[123] women from Turkey moved to study in Northern Cyprus since many universities there did not apply any ban on headscarf.[124] Whilst many Turkish Cypriot women no longer wear headscarves, recent immigrants from Turkey, settled in villages in northern Cyprus, do.[125]

Former USSR

The word "hijab" used only for middle-east style of hijab, and such style of hijab was not commonly worn by Muslims there until the fall of the USSR. Some Islamic adherents (like Uzbeks) used to wear the paranja, while others (Chechens, Kara-Chai, Kazakhs, Turkmens, etc.) wore traditional scarves the same way as a bandana. And have own traditional styles of headgear which are not called by the word "hijab".

Africa

Cameroon

On July 12, 2015, two women dressed in religious garments blew themselves up in Fotokol, killing 13 people. Following the attacks, since July 16, Cameroon banned the wearing of full-face Islamic veils, including the burqa, in the Far North region. Governor Midjiyawa Bakari of the mainly Muslim region said the measure was to prevent further attacks.[126]

Chad

Reuters.com reported on June 17, 2015: "Chad said on Wednesday it had arrested at least five suspects and had banned religious burqas after suicide bombings blamed on the Islamist Boko Haram killed 34 people...." Chad, a mostly Muslim country, also said it would ban head-to-toe burqas and religious turbans.

"Even the burqas for sale in the markets will be withdrawn," said Prime Minister Kalzeube Pahimi Deubet, who met religious leaders on Wednesday to discuss the measures.[127]

Congo-Brazzaville

The full-face Islamic veil was banned in May 2015 in public places in Congo-Brazzaville, to "counter terrorism", although there has not been an Islamist attack in the country.[126]

Gabon

On July 15, 2015, Gabon announced a ban on the wearing of full-face veils in public and places of work. The mainly Christian country said it was prompted to do so because of the attacks in Cameroon.[126]

Asia-Pacific

Australia

In September 2011, Australia's most populous State, New South Wales, passed the Identification Legislation Amendment Act 2011 to require a person to remove a face covering if asked by a state official. The law is viewed as a response to a court case of 2011 where a woman in Sydney was convicted of falsely claiming that a traffic policeman had tried to remove her niqab.[128]

The debate in Australia is more about when and where face coverings may legitimately be restricted.[129] In a Western Australian case in July 2010, a woman sought to give evidence in court wearing a niqab. The request was refused on the basis that the jury needs to see the face of the person giving evidence.[129]

Myanmar

In June 21, 2015, at a conference in Yangon held by the Organization for the Protection of Race and Religion, a group of monks locally called Ma Ba Tha declared that the headscarves "were not in line with school discipline," recommending the Burmese government to ban the wearing of hijabs by Muslim schoolgirls and to ban the killing of innocent animals on their Eid holiday.[130]

North America

Canada

On 12 December 2011, the Canadian Minister of Citizenship and Immigration issued a decree banning the niqab or any other face-covering garments for women swearing their oath of citizenship; the hijab was not affected[131] This edict was later overturned by a Court of Appeal on the grounds of being unlawful.

Mohamed Elmasry, a controversial former president of the Canadian Islamic Congress (CIC), has stated that only a small minority of Muslim Canadian women actually wear these types of clothing. He has also said that women should be free to choose, as a matter of culture and not religion, whether they wear it.[132] The CIC criticized a proposed law that would have required all voters to show their faces before being allowed to cast ballots. The group described the idea as unnecessary, arguing that it would only promote discrimination against Muslims and provide "political mileage among Islamophobes".[133]

In February 2007, soccer player Asmahan Mansour, part of the team Nepean U12 Hotspurs, was expelled from a Quebec tournament for wearing her headscarf. Quebec soccer referees also ejected an 11-year-old Ottawa girl while she was watching a match, which generated a public controversy.[134]

In November 2013, a bill commonly referred to as the Quebec Charter of Values was introduced in the National Assembly of Quebec by the Parti Québécois that would ban overt religious symbols in the Quebec public service. Thus would include universities, hospitals, and public or publicly funded schools and daycares.[135] Criticism of this decision came from The Globe and Mail newspaper, saying that such clothing, as worn by "2011 Nobel Peace Prize winner Tawakkul Karman", was "Good enough for Nobel, but not for Quebec".[136] In 2014 however, the ruling Parti Québécois was defeated by the Liberal Party of Quebec and no legislation was enacted regarding religious symbols.

Mexico

There is no ban on any Muslim clothing items. The first article of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States protects people against discrimination based on several matters including religion, ethnic origin and national origin.[137] Article 6 of the Constitution grants Libertad de Expresión (freedom of expression) to all Mexicans which includes the way people choose to dress.[137]

The Muslim community is a minority; according to the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life there were approx. 3,700 Muslims in Mexico as of 2010, representing 0.003% percent of the total population.[138] There is an almost complete lack of knowledge of Islam in Mexico, and any interest is more out of curiosity and tolerance than hatred or racism.[139] Some Muslims suggest that it is easier to fit in if they are lax with the rules of their religion, for example by wearing regular clothing.[140] Muslim women's clothing can vary from non-Muslim clothing to a hijab or a chador.

United States

The people of the United States have a firm First Amendment protection of freedom of speech from government interference that explicitly includes clothing items, as described by Supreme Court cases such as Tinker v. Des Moines.[141] As such, a ban on Islamic clothing is considered presumptively invalid by U.S. socio-political commentators such as Mona Charen of National Review.[142] Journalist Howard LaFranchi of The Christian Science Monitor has referred to "the traditional American respect for different cultural communities and religions under the broad umbrella of universal freedoms" as forbidding the banning of Islamic dress. In his prominent June 2009 speech to the Muslim World in Cairo, President Barack Obama called on the West "to avoid dictating what clothes a Muslim woman should wear", and he elaborated that such rules involve "hostility" towards Muslims in "the pretense of liberalism".[143]

Most gyms, fitness clubs, and other workout facilities in the United States are mixed-sex, so exercise without a hijab or burqa can be difficult for some observant Muslim women. Maria Omar, director of media relations for the Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America (IFANCA), has advised Muslim women to avoid these complexes entirely. Some women decide to wear something colloquially known as the "sports hijab". Similarly, Muslim women may feel uncomfortable around other women with traditionally revealing American outfits, especially during the summer "bikini season". An outfit colloquially known as the burqini allows Muslim women to swim without displaying any significant amount of skin.[144]

Compared to Western Europe, there have been relatively few controversies surrounding the hijab in everyday life, and Muslim garb is commonly seen in major US cities. One exception is the case of Sultaana Freeman, a Florida woman who had her driver's license cancelled due to her wearing of the niqab in her identification photo. She sued the state of Florida for religious discrimination, though her case was eventually thrown out.

See also

- Headscarf controversy in Turkey

- Hijab controversy in Quebec

- Islam and clothing

- Multiculturalism

- Muslims in Europe

- 'Snow (Pamuk novel)

- Women in Muslim societies

References

- ↑ "Headscarf ban sparks debate over Kosovo's identity" news.bbc.co.uk' 24 August 2010. Link retrieved 24 August 2010

- ↑ "AZERBAIJAN: Feud over ban on Islamic head scarves fuels fears of Iranian meddling". 30 December 2010.

- 1 2 Abdelhadi, Magdi Tunisia attacked over headscarves, BBC News, 26 September 2006. Accessed 6 June 2008.

- ↑ Turkey headscarf ruling condemned Al Jazeera English (7 June 2008). Retrieved on February 2009.

- ↑ "Syria bans face veils at universities". 19 July 2010 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Richard Hamilton (6 October 2006) Morocco moves to drop headscarf BBC News (BBC). Retrieved on 13 February 2009.

- ↑ Reformatorisch dagblad: Brussel tegen boerkaverbod, 30 November 2006.

- ↑ "Tawakkul Karman - First Arab Woman and Youngest Nobel Peace Laureate".

- ↑ Blair's concerns over face veils BBC News Online. 17 October 2006.

- ↑ French MPs back headscarf ban BBC News (BBC). Retrieved on 13 February 2009.

- ↑ "Education Code. L811-1 §2" (in French). Legifrance.gouv.fr. 1984-01-26. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ↑ Guardian: Livingstone decries vilification of Islam, 20 November 2006.

- ↑ Ipsos MORI Muslim Women Wearing Veils.

- ↑ Atlantic Council

- ↑ Scott, 2007, pg. 5

- ↑ The Telegraph Netherlands to Ban the Burka

- ↑ Flanders News:Veiled woman breaks police officer's nose

- ↑ Willsher, Kim (1 July 2014). "France's burqa ban upheld by human rights court". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ "Burqa Ban: Countries that Have Banned Burqa & Niqab Completely or Partially". National Views. 20 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Amer, Sahar (2014). What Is Veiling?. The University of North Carolina Press (Kindle edition). p. 61.

- ↑ Mendes, Jessica (13 November 2001). "Taliban rulers curtail women's freedom, health care". Canadian Medical Association Journal. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ Lawrence, Quil (13 July 2010). "Peace In Afghanistan At What Cost To Its Women?". NPR. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ Kiko Itasaka (May 14, 2010). "Under that burqa, lipstick and high heels". NBC News.

- ↑ "Chad arrests five and bans burqa after suicide bombings". 17 June 2016 – via Reuters.

- ↑ "Chad Bans Islamic Face Veils". 17 June 2015.

- ↑ United Press Service (UP) (26 January 1958). "Egypt's Women Foil Attempt to Restrict". Sarasota Herald-Tribune (114): 28. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- ↑ Slackman, Michael (28 January 2007). "In Egypt, a New Battle Begins Over the Veil". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- 1 2 "Fatwa stirs heated debate over face-veiling in Kuwait". Kuwait Times. 9 October 2009. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 "A look at the wearing of veils, and disputes on the issue, across the Muslim world". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

- ↑ Ranyah Sabry (17 April 2007) Egypt anchorwomen battle for hijab BBC News (BBC). Retrieved on 13 February 2009.

- ↑ Correspondent, By Ramadan Al Sherbini, (22 October 2006). "Veil war breaks out on Egypt university campus".

- ↑ "The Islamic Network for Woman and Families".

- ↑ "Egypt: Niqab Ban Stirs Controversy · Global Voices". 9 October 2009.

- ↑ "How You See It: Egyptian campus bans niqab - WORLDFOCUS". 8 October 2009.

- ↑ "EGYPT: Controversial ban on niqab in dorms - University World News".

- ↑ Egypt court upholds niqab ban for university examinations

- ↑ Correspondent, By Ramadan Al Sherbini, (20 January 2010). "Egypt court revokes ban on niqab at exam halls".

- ↑ Ibrahim, Baher. "This trend of young Muslim girls wearing the hijab is disturbing." The Guardian. Tuesday 23 November 2010. Retrieved on 30 December 2013.

- ↑ Verma, Sonia. "Cairo's 'hijab-free' zones trigger cries of hypocrisy." The Globe and Mail. Wednesday 29 February 2012. Updated Monday 10 September 2012. Retrieved on 28 December 2013.

- ↑ John M. Echols, Hassan Shadily, An English-Indonesian dictionary: Kamus Inggris-Indonesia Kamus Inggris-Indonesia University Press: 1975, ISBN 0-8014-9859-7, 660 pages

- ↑ S. A. Niessen, Ann Marie Leshkowich, Carla Jones, Re-orienting fashion: the globalization of Asian dress: Berg Publishers: 2003: ISBN 1-85973-539-8, ISBN 978-1-85973-539-8, 283 pages pp 206-207

- ↑ Insideindonesia.org

- ↑ "Aceh-eye.org".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ramezani, Reza (2010). Hijab dar Iran az Enqelab-e Eslami ta payan Jang-e Tahmili [Hijab in Iran from the Islamic Revolution to the end of the Imposed war] (Persian), Faslnamah-e Takhassusi-ye Banuvan-e Shi’ah [Quarterly Journal of Shiite Women], Qom: Muassasah-e Shi’ah Shinasi, ISSN 1735-4730

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Milani, Farzaneh (1992). Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers, Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, p. 19, 34-37, ISBN 9780815602668

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 El Guindi, Fadwa (1999). Veil: Modesty, Privacy and Resistance, Oxford; New York: Berg Publishers; Bloomsbury Academic, p. 3, 13-16, 130, 174-176, ISBN 9781859739242

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hoodfar, Homa (fall 1993). The Veil in Their Minds and On Our Heads: The Persistence of Colonial Images of Muslim Women, Resources for feminist research (RFR) / Documentation sur la recherche féministe (DRF), Vol. 22, n. 3/4, p. 5-18, Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto (OISE), ISSN 0707-8412

- 1 2 Fathi, Asghar (1985). Women and the Family in Iran, Social, economic, and political studies of the Middle East, Vol. 38, Leiden: Brill, p. 7, 57, 61-2, 107-109, ISBN 9789004074262

- ↑ Scarce, Jennifer M. (1975). The Development of Women’s Veils in Persia and Afghanistan, Costume, Journal of the Costume Society, Vol. 9. (1), Leeds: Maney Publishing, p. 4, ISSN 0590-8876

- ↑ Peck, Elsie H. (1992). "Clothing viii. In Persia from the Arab conquest to the Mongol invasion", in Yarshater, Ehsan: Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. V, Fasc. 7, p. 760-778, Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, ISBN 9780939214792

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Heath, Jennifer (2008). The Veil: Women Writers on Its History, Lore, and Politics, Berkeley; Los Angeles: University of California Press, p. 66, 252-253, 256, 260, ISBN 9780520255180

- 1 2 Keddie, Nikki R. (2005). "2. The past and present of women in the Muslim world" in Moghissi, Haideh: Women and Islam: Images and realities, Vol. 1, p. 53-79, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge; Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9780415324199

- ↑ Mitchell, Colin P. (2011). New Perspectives on Safavid Iran: Empire and Society, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Taylor & Francis, p. 98-99, 104, ISBN 9780415774628

- 1 2 Floor, Willem M. (2003). Agriculture in Qajar Iran, Washington, DC: Mage Publishers, p. 113, 268, ISBN 9780934211789

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chehabi, Houchang Esfandiar (2003): "11. The Banning of the Veil and Its Consequences" in Cronin, Stephanie: The Making of Modern Iran: State and Society under Riza Shah, 1921-1941, p. 203-221, London; New York: Routledge; Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9780415302845

- 1 2 Bullock, Katherine (2002). Rethinking Muslim Women and the Veil: Challenging Historical & Modern Stereotypes, Herndon, Virginia; London: International Institute of Islamic Thought, p. 90-91, ISBN 9781565642874

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Paidar, Parvin (1995): Women and the Political Process in Twentieth-Century Iran, Cambridge Middle East studies, Vol. 1, Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 106-107, 214-215, 218-220, ISBN 9780521473408

- 1 2 Majd, Mohammad Gholi (2001). Great Britain and Reza Shah: The Plunder of Iran, 1921–1941, Gainesville: University Press of Florida, p. 209-213, 217-218, ISBN 9780813021119

- 1 2 3 Curtis, Glenn E.; Hooglund, Eric (2008). Iran: A Country Study, 5th ed, Area handbook series, Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, p. 28, 116-117, ISBN 9780844411873

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Katouzian, Homa (2003). "2. Riza Shah’s Political Legitimacy and Social Base, 1921–1941" in Cronin, Stephanie: The Making of Modern Iran: State and Society under Riza Shah, 1921-1941, p. 15-37, London; New York: Routledge; Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9780415302845

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Katouzian, Homa (2004). "1. State and Society under Reza Shah" in Atabaki, Touraj; Zürcher, Erik-Jan: Men of Order: Authoritarian Modernisation in Turkey and Iran, 1918-1942, p. 13-43, London; New York: I.B. Tauris, ISBN 9781860644269

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Katouzian, Homa (2006). State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis, 2nd ed, Library of modern Middle East studies, Vol. 28, London; New York: I.B. Tauris, p. 33-34, 335-336, ISBN 9781845112721

- ↑ Fatemi, Nasrallah Saifpour (1989). Reza Shah wa koudeta-ye 1299 (Persian), Rahavard – A Persian Journal of Iranian Studies, Vol. 7, n. 23, p. 160-180, Los Angeles: Society of the Friends of the Persian Culture, ISSN 0742-8014

- 1 2 3 Beeman, William Orman (2008). The Great Satan vs. the Mad Mullahs: How the United States and Iran Demonize Each Other, 2nd ed, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 108, 152, ISBN 9780226041476

- 1 2 Abrahamian, Ervand (2008). A History of Modern Iran, Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 84, 94-95, ISBN 9780521528917

- 1 2 3 4 Ramezani, Reza (2008). Hijab dar Iran, dar doure-ye Pahlavi-ye dovvom [Hijab in Iran, the second Pahlavi era] (Persian), Faslnamah-e Takhassusi-ye Banuvan-e Shi’ah [Quarterly Journal of Shiite Women], Qom: Muassasah-e Shi’ah Shinasi, ISSN 1735-4730

- 1 2 Gheiby, Bijan; Russell, James R.; Algar, Hamid (1990). "Čādor (2)" in Yarshater, Ehsan: Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 6, p. 609-611, London; New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 9780710091321

- 1 2 Algar, Hamid (2001). Roots of the Islamic Revolution in Iran: Four Lectures, Oneonta, New York: Islamic Publications International (IPI), p. 84, ISBN 9781889999265

- 1 2 Ahmadi, Khodabakhsh; Bigdeli, Zahra; Moradi, Azadeh; Seyed Esmaili, Fatholah (summer 2010): Rabete-ye e’teqad be hijab va asibpaziri-e fardi, khanvedegi, va ejtema’i [Relation between belief in hijab and individual, familial and social vulnerability] (Persian), Journal of Behavioral Sciences (JBS), Vol. 4, n. 2, p. 97-102, Tehran: Baghiatallah University of Medical Sciences, ISSN 2008-1324

- ↑ Publicradio.org

- ↑ Headscarf ban sparks debate over Kosovo's identity news.bbc.co.uk 24 August 2010. Link retrieved 24 August 2010

- ↑ World Bulletin Kosovo elects first lawmaker to wear a headscarf

- ↑ Hjh Halimatussaadiah bte Hj Kamaruddin v Public Services Commission, Malaysia & Anor [1994] 3 MLJ 61.

- ↑ Hassim, Nurzihan (2014). "A Comparative Analysis on Hijab Wearing in Malaysian Muslimah Magazines" (PDF). SEARCH: The Journal of the South East Asia Research Center for Communications and Humanities. 6 (1): 79–96. ISSN 2229-872X. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- 1 2 Leong, Trinna. "Malaysian Women Face Rising Pressure From Muslim 'Fashion Police'" (Archive). Huffington Post. July 21, 2015. Retrieved on August 28, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Boo, Su-lyn. "Tudung industry in Malaysia: Cashing in on conservative Islam" (Archive). The Malay Mail. May 9, 2015. Retrieved on August 28, 2015. See version at Yahoo! News.

- ↑ Koh, Jaime and Stephanie Ho. Culture and Customs of Singapore and Malaysia (Cultures and Customs of the World). ABC-CLIO, 22 June 2009. ISBN 0313351163, 9780313351167. p. 31.

- ↑ Fernandez, Celine. "Why Some Women Wear a Hijab and Some Don’t" (Archive). The Wall Street Journal. April 18, 2011. Retrieved on August 28, 2015.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - Africa - Morocco moves to drop headscarf".

- 1 2 "Clothing in Pakistan and other Local Customs Reviews".

- 1 2 "A Traveling Girl's Guide to Clothing in Muslim Countries".

- ↑ Marfuqi, Kitab ul Mar'ah fil Ahkam, pg 133

- ↑ Abdullah Atif Samih (7 March 2008). "Do women have to wear niqaab?". Islam Q&A. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ Munajjid (7 March 2008). "Shar'i description of hijab and niqaab". Islam Q&A. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ "Correct view on the ruling on covering the face - islamqa.info".

- ↑ Said al Fawaid (7 March 2008). "Articles about niqab". Darul Ifta. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ Moqtasami (1979), pp. 41-44

- ↑ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.117-118.

- ↑ "Headscarf incident in Sudan highlights a global trend". 18 September 2013.

- ↑ AFP (4 November 2013). "Woman faces whipping over refusal to cover hair in Sudan".

- ↑ "Syria bans face veils at universities". BBC News. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - Africa - Tunisia moves against headscarves".

- ↑ Tunisian revolution

- 1 2 20/21 May 2006 "Uproar in Turkey Over the Hijab." Headscarf By Michael Dickinson

- ↑ Zafar Bangash (16–31 May 1999) Turkey's secular fundamentalists target woman over hijab Muslimedia. Retrieved on February 2009.

- ↑ Rainsford, Sarah (2006-11-07). "Headscarf issue challenges Turkey". BBC News.

- ↑ "Covered women decreased,we do not look like Malaysia". A&G research company. 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ↑ Rainsford, Sarah (2007-10-02). "Women condemn Turkey constitution". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Clark-Flory, Tracy (2007-04-23). "Head scarves to topple secular Turkey?". Salon. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Ayman, Zehra; Knickmeyer, Ellen. Ban on Head Scarves Voted Out in Turkey: Parliament Lifts 80-Year-Old Restriction on University Attire. The Washington Post. 2008-02-10. Page A17.

- ↑ Derakhshandeh, Mehran. Just a headscarf? Tehran Times. Mehr News Agency. 2008-02-16.

- ↑ Jenkins, Gareth. Turkey's Constitutional Changes: Much Ado About Nothing? Eurasia Daily Monitor. The Jamestown Foundation. 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Turkish president approves amendment lifting headscarf ban. The Times of India. 2008-02-23.

- ↑ Sabrina Tavernise (5 June 2008). "Turkey's high court overrules government on head scarves". New York Times. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ↑ Euronews (08.10.2013) The headscarf ban in public institutions in Turkey was officially lifted

- 1 2 Cypriot Attire Project, Cyprus History in Brief

- ↑ Cypriot Customs and Traditions, Kypros-Cyprus

- ↑ Dr. Danos, Antonis, "Aphrogennimeni", Department of Art and Design, Intercollege, Nicosia, 2006

- ↑ "MKs discuss France-like burka ban". Jerusalem Post.

- ↑ RAI, SARITHA (2004). "A Religious Tangle Over the Hair of Pious Hindus" (JULY 14, 2004). The New York Times. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ Heath, edited by Jennifer (2008). The veil : women writers on its history, lore, and politics. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 44–56. ISBN 9780520250406. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "Women and the Hijab in the Intifada", Rema Hammami Middle East Report, May–August 1990

- ↑ Rubenberg, C., Palestinian Women: Patriarchy and Resistance in the West Bank (USA, 2001) p.230

- ↑ Rubenberg, C., Palestinian Women: Patriarchy and Resistance in the West Bank (USA, 2001) p.231

- ↑ xinhuanet.com, 2010-01-03

- ↑ Hamas Bans Women Dancers, Scooter Riders in Gaza Push By Daniel Williams, Bloomberg, 30 November 2009

- ↑ "Removed: news agency feed article". 9 December 2015 – via The Guardian.

- 1 2 mercurynews.com

- ↑ Mariti, Giovanni, Travels in the Island of Cyprus, p.3, 1769

- ↑ Eicher, Joanne Bubolz, Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time, p.35, 1995

- ↑ Irwin, Elizabeth K., Reading Herodotus: A Study of the Logoi in Book 5 of Herodotus' Histories, p.273, 2007

- ↑ Athanasiadis, Iason, "Northern Cyprus espouses 'Islam lite'", Daily Star

- ↑ Haber KKTC, 07 June 2011 Ban on headscarf was removed in Turkey

- ↑ Tavernise, Sabrina, "Under a Scarf, a Turkish Lawyer Fighting to Wear It", The New York Times, 9 February 2008

- ↑ Cyprus: Culture and language, Mephisto

- 1 2 3 Cameroon bans Islamic face veil after suicide bombings, July 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-18.

- ↑ Chad arrests five and bans burqa after suicide bombings, June 17, 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-26.

- ↑ Australia Muslim Veil Law Requires Women To Remove Face-Covering Niqab In New South Wales, 3 May 2012

- 1 2 The Full Face Covering Debate: An Australian Perspective by Renae BARKER

- ↑ Hijab Ban 2015: Buddhist Monks Propose Anti-Muslim Measure On Burmese Schoolgirls, June 22, 2015

- ↑ Face veils banned for citizenship oaths. CBC. Published 2011-12-12. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

- ↑ "Muslim group calls for burka ban". CBC News. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ Joan, Bryden (27 October 2007). "New bill to ban veiled voters". Globe and Mail.

- ↑ "Ontario, Quebec differ over soccer head scarf ban". CBC News. 26 February 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ Charter affirming the values of State secularism and religious neutrality and of equality between women and men, and providing a framework for accommodation requests

- ↑ Good enough for Nobel, but not for Quebec, The Globe and Mail

- 1 2 "Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos". Congress of the Union of the United Mexican States. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ↑ "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ↑ juntaislamica.com. "Los musulmanes de Monterrey (México) - Webislam".

- ↑ juntaislamica.com. "Musulmanes de México - Webislam".

- ↑ "Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School Dist.".

- ↑ Mona Charen (7 July 2009). "Could the U.S. Ban the Burqa Too?". National Review. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ LaFranchi, Howard (23 June 2009). "In battle of the burqa, Obama and Sarkozy differ". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ "Paris pool bans Muslim woman in 'burqini'". Agence France-Presse. 12 August 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- Scott, Joan Wallach (2007). "The Politics of the Veil". Princeton University Press.

External links

![]() Media related to Hijabs by country at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hijabs by country at Wikimedia Commons

- Burqa ban: What it means for the West – TCN News

- VEIL Project – Values, Equality and Differences in Liberal Democracies. Debates about Muslim Headscarves in Europe (University of Vienna)

- Q&A: Muslim headscarves from BBC News

- Shabina Begum case: School wins Muslim dress appeal (22 March 2006)

- The Veil and the British Male Elite

- Behind the Scarfed Law, There is Fear – Alain Badiou