Western black rhinoceros

| Western black rhinoceros | |

|---|---|

| |

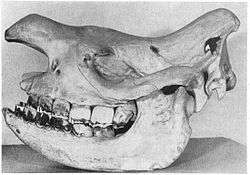

| Holotype specimen, a female shot in 1911 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genus: | Diceros |

| Species: | D. bicornis |

| Subspecies: | † D. b. longipes |

| Trinomial name | |

| Diceros bicornis longipes Zukowsky, 1949 | |

The western black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis longipes) or West African black rhinoceros is a subspecies of the black rhinoceros, declared extinct by the IUCN in 2011.[1][2] The western black rhinoceros was believed to have been genetically different from other rhino subspecies.[3] It was once widespread in the savanna of sub-Saharan Africa, but its numbers declined due to poaching. The western black rhinoceros resided primarily in Cameroon, but surveys since 2006 have failed to locate any individuals.

Taxonomy

This subspecies was named Diceros bicornis longipes by Ludwig Zukowsky in 1949. The word “longipes” is of Latin origin, combining longus (“far, long”) and pēs (“foot”). This refers to the species’ long distal limb segment, one of many special characteristics of the species. Other distinct features of the western black rhino included the square based horn, first mandibular premolar retained in the adults, simple formed crochet of the maxillary premolar, and premolars commonly possessed crista.[4]

The population was first discovered in Southwest Chad, Central African Republic (CAR), North Cameroon, and Northeast Nigeria.[5]

Description

The western black rhinoceros measured 3–3.75 m (9.8–12.3 ft) long, had a height of 1.4–1.8 m (4.6–5.9 ft), and weighed 800–1,400 kg (1,800–3,100 lb).[6] It had two horns, the first measuring 0.5–1.4 m (1.6–4.6 ft) and the second 2–55 cm (0.79–21.65 in). Like all Black Rhinos, they were browsers, and their common diet included leafy plants and shoots around their habitat. During the morning or evening, they would browse for food. During the hottest parts of the day, they slept or wallowed.[7] They inhabited much of sub-Saharan Africa.[8] Many people believe their horns held medicinal value, which led to heavy poaching. However, this belief has no grounding in scientific fact.[8] Like most black rhinos, they are believed to have been nearsighted and would often rely on local birds, such as the red-billed oxpecker, to help them detect incoming threats.[9]

Habitat and distribution

The black rhino, of which the western black rhinoceros is a subspecies, was most commonly located in several countries towards the southeast region of the continent of Africa. The native countries of the black rhino included: Angola, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, United Republic of Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Cameroon, Chad, Rwanda, Botswana, Malawi, Swaziland, and Zambia.[10] There were several subspecies found in the western and southern countries of Tanzania through Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, to the northern and north-western and north-eastern parts of South Africa. The Black Rhino's most abundant population was found in South Africa and Zimbabwe, with a smaller population found in southern Tanzania. The Western subspecies of the Black Rhino was last recorded in Cameroon but is now considered to be extinct.[2] However, other subspecies were introduced again into Botswana, Malawi, Swaziland and Zambia.[10]

Population and decline

The western black rhinoceros was heavily hunted in the beginning of the 20th century, but the population rose in the 1930s after preservation actions were taken. As protection efforts declined over the years, so did the number of western black rhinos. By 1980 the population was in the hundreds. No animals are known to be held in captivity, however it was believed in 1988 that approximately 20–30 were being kept for breeding purposes.[11] Poaching continued and by 2000 only an estimated 10 survived. In 2001, this number dwindled to only five. While it was believed that around thirty still existed in 2004, this was later found to be based upon falsified data.[12]

The western black rhino emerged about 7 to 8 million years ago. It was a sub-species of the black rhino. For much of the 1900s, its population was the highest out of all the rhino species at almost 850,000 individuals. There was a 96% population decline in black rhinos, including the western black rhino, between 1970 and 1992. Widespread poaching is concluded to be partly responsible for bringing the species close to extinction, along with farmers killing rhinos to defend their crops in areas close to rhino territories,[13] and trophy hunting.[14]

By 1995 the number of western black rhinos had dropped to 2,500 individuals. The sub-species was declared officially extinct in 2011,[12] with its last sighting reported in 2006 in Cameroon's Northern Province.[15][16]

In 2006, for six months, the NGO Symbiose and veterinarians Isabelle and Jean-François Lagrot with their local teams examined the common roaming ground of Diceros bicornis longipes in the northern province of Cameroon to assess the status of the last population of the western black rhino subspecies. For this experiment, 2500 km of patrol effort resulted in no sign of rhino presence over the course of six months. The teams had concluded that the rhino was extinct approximately five years before it was officially declared so by the IUCN.[12]

Protection attempts

There were many attempts to revive Western Black and Northern White. Rhino sperm was conserved in order to artificially fertilize females to produce offspring. Some attempts were successful, but most experiments failed due to different reasons, including stress and reduced time in the wild.[17]

In 1999 (WWF) published a report called "African Rhino: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan." This report recommended that all surviving species of Western Black Rhino should be captured and placed in a specific region of modern Cameroon, in order to facilitate monitoring and reduce the attack rates of poachers. This experiment failed due to corruption. It demanded large amount of money, and the risk of failure was very high.

Western Black Rhinos and other subspecies were conserved in National Conservative parks and live species are still there. They live there under the protection of the government and all conditions are made for their survival. To monitor and protect white rhinos WWF focuses on better-integrated intelligence gathering networks on rhino poaching and trade, more antipoaching patrols and better equipped conservation law enforcement officers. WWF is setting up an Africa-wide rhino database using rhino horn DNA analysis (RhoDIS), which contributes to forensic investigations at the scene of the crime and for court evidence to greatly strengthen prosecution cases. WWF supports accredited training in environmental and crime courses, some of which have been adopted by South Africa Wildlife College. Special prosecutors have been appointed in countries like Kenya and South Africa to prosecute rhino crimes in a bid to deal with the mounting arrests and bring criminals to face swift justice with commensurate penalties.

Traditional Chinese medicine

In the 1950s, Mao Zedong effectively encouraged traditional Chinese medicine in an attempt to counter Western influences. While attempting to modernize this industry, several species were hunted. According to the official data published by the SATCM, 11,146 botanical and 1,581 zoological species, as well as 80 minerals were used.[18] The Western Black Rhino was also hunted due to the value of its horn, which was believed to have the power to cure specific ailments and to be effective at detecting poisons (due to its high alkaline content).[19] Price for horns could be high, for example 1 kg of horn could cost more than 50,000 US dollars, and the extinction of the species only increases the rarity and value of the horn.[20]

Poaching, along with the lack of conservation efforts from the IUCN, contributed to the extinction of the subspecies.[21]

Other uses for the horn

Rhino horns were used in making ceremonial knife handles called "Janbiya".[22] The hilt type known as saifani uses rhinoceros horn as material and is a symbol of wealth and status due to its cost.

In modern times, horns of other rhinoceros species are very valuable and can cost up to $100,000 per kg in places of high demand (e.g. Vietnam). An average horn may weigh between 1 and 3 kg. While locally respected doctors in Vietnam vouch for the rhino horns' cancer-curing properties, there is no scientific evidence for this or any other imputed medical property of the horns.[23]

References

- 1 2 Emslie, R. (2016). "Diceros bicornis ssp. longipes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- 1 2 Boettcher, Daniel (November 8, 2013). "Western black rhino declared extinct". BBC. Retrieved 2011-11-10.

- ↑ "Western Black Rhino Poached Out of Existence; Declared Extinct, Slack Anti-Poaching Efforts Responsible". International Business Times, 2011-11-14. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ Groves, Colin; Grubb, Peter (November 1, 2011). Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1421400938.

- ↑ Smith, Hillman K.; Groves, C.P. (1994). "Diceros bicornis" (PDF). Mammalian Species. no. 455 (455): 1–8, figs. 1–3. doi:10.2307/3504292. JSTOR 3504292.

- ↑ Black Rhinoceros, Arkive

- ↑ "Black Rhino – Diceros bicornis". Rhino Research Center. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- 1 2 Gwin, Peter (March 2012). "Rhino Wars". National Geographic. 221 (3): 106–20. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ Plotz, Roan (May–June 2012). "Burdened Beast" (PDF). Australian Geographic. 108: 16–17.

- 1 2 Emslie, R. "Diceros bicornis". IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Cohn, Jeffery P. (1988). "Halting the rhino's demise". BioScience. 38 (11): 740–744. doi:10.2307/1310780. JSTOR 1310780.

- 1 2 3 Lagrot, Isabelle (2007). "Probable extinction of the western black rhino, Diceros bicornis longipes: 2006 survey in northern Cameroon". Pachyderm. 43: 19.

- ↑ "black rhino". scientific america.

- ↑ "black rhino extinction". voice of america.

- ↑ Coffin, Bill (2013). "The Western Black Rhino [Extinct 2013]". National Underwriter/Life & Health Financial Services. 117 (8): 48.

- ↑ Harley, E. H.; Baumgarten, I; Cunningham, J; O'Ryan, C (2005). "Genetic variation and population structure in remnant populations of black rhinoceros, Diceros bicornis, in Africa". Molecular Ecology. 14 (10): 2981–90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02660.x. PMID 16101768.

- ↑ "White rhino extinction". WWF.

- ↑ Xu, Q.; Bauer, R.; Hendry, B. M.; Fan, T. P.; Zhao, Z.; Duez, P.; Simmonds, M. S.; Witt, C. M.; Lu, A.; Robinson, N.; Guo, D. A.; Hylands, P. J. (2013). "The quest for modernisation of traditional Chinese medicine". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 13: 132. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-13-132. PMC 3689083

. PMID 23763836.

. PMID 23763836. - ↑ "Rhino Horn Use: Fact vs. Fiction". Nature (TV series). PBS. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ "Rhino horns". the atlantic.

- ↑ Knight, Matthew (6 November 2013). "Western Black Rhino Declared Extinct." CNN..

- ↑ Platt, John R. (13 November 2013) "How the Western Black Rhino became extinct", Scientific American.

- ↑ Guilford, Gywnn (13 May 2013). "Why Does a Rhino Horn Cost $300,000? Because Vietnam Thinks It Cures Cancer and Hangovers." The Atlantic.

External links

Data related to Diceros bicornis longipes at Wikispecies

Data related to Diceros bicornis longipes at Wikispecies