War of the Fifth Coalition

| War of the Fifth Coalition | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars and the Coalition Wars | |||||||||

Napoleon at Wagram, painted by Horace Vernet | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Fifth Coalition:

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

340,000 Austrians,[1] 85,000 British[2] | 275,000[3] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 100,000+ | 90,000+ | ||||||||

The War of the Fifth Coalition was fought in the year 1809 by a coalition of the Austrian Empire and the United Kingdom against Napoleon's French Empire and Bavaria. Major engagements between France and Austria, the main participants, unfolded over much of Central Europe from April to July, with very high casualty rates for both sides. Britain, already involved on the European continent in the ongoing Peninsular War, sent another expedition, the Walcheren Campaign, to the Netherlands in order to relieve the Austrians, although this effort had little impact on the outcome of the conflict. After much campaigning in Bavaria and across the Danube valley, the war ended favourably for the French after the bloody struggle at Wagram in early July.

The resulting Treaty of Schönbrunn was the harshest that France had imposed on Austria in recent memory. Metternich and Archduke Charles had the preservation of the Habsburg Empire as their fundamental goal, and to this end the former succeeded in making Napoleon seek more modest goals in return for promises of Franco-Austrian peace and friendship.[4] Nevertheless, while most of the hereditary lands remained part of Habsburg territories, France received Carinthia, Carniola, and the Adriatic ports, while Galicia was given to the Poles and the Salzburg area of the Tyrol went to the Bavarians.[4] Austria lost over three million subjects, about one-fifth of her total population,[5] as a result of these territorial changes.

Although the Fifth Coalition ended, Britain, Spain and Portugal remained at war with France in the ongoing Peninsular War. There was peace in central and eastern Europe until Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812, which led to the formation of the Sixth Coalition in 1813.

Background

Europe had been embroiled in warfare, pitting revolutionary France against a series of coalitions, nearly continuously since 1792. After five years of war, the French Republic subdued the First Coalition in 1797. A Second Coalition was formed in 1798, only to be defeated. In March 1802, France (now under Napoleon, as First Consul) and Great Britain, its one remaining enemy, agreed to end hostilities under the Treaty of Amiens. For the first time in ten years, all of Europe was at peace. However, many disagreements between the two sides remained unresolved, and implementing the agreements they had reached at Amiens seemed to be a growing challenge. Britain resented having to turn over all of its colonial conquests since 1793 when France was permitted to retain most of its conquered territory in Europe. France, meanwhile, was upset that British troops had not evacuated the island of Malta.[6] In May 1803, Britain declared war on France.

Third Coalition (1804–1805)

With the resumption of hostilities, Napoleon (proclaimed Emperor in 1804) planned an invasion of England, spending the better part of the next two years (1803–05) on this objective. In December 1804, an Anglo-Swedish agreement led to the creation of the Third Coalition. British Prime Minister William Pitt spent 1804 and 1805 in a flurry of diplomatic activity geared towards forming a new coalition against France and neutralising the threat of invasion. Mutual suspicion between the British and the Russians eased in the face of several French political mistakes, and by April 1805, the two had signed a treaty of alliance.[7] Alarmed by Napoleon's consolidation of northern Italy into a kingdom under his rule, and keen on revenge for having been defeated twice in recent memory by France, Austria would join the coalition a few months later.[8]

In August 1805, the French Grande Armée invaded the German states in hopes of knocking Austria out of the war before Russian forces could intervene. On 25 September, after great secrecy and feverish marching, 200,000[9] French troops began to cross the Rhine on a front of 160 miles (260 km).[10] Mack had gathered the greater part of the Austrian army at the fortress of Ulm in Bavaria. Napoleon hoped to swing his forces northward and perform a wheeling movement that would find the French at the Austrian rear. The Ulm Maneuver was well executed, and on 20 October Mack and 23,000 Austrian troops surrendered at Ulm, bringing the total number of Austrian prisoners in the campaign to 60,000.[10] The French captured Vienna in November and went on to inflict a decisive defeat on a Russo-Austrian army at Austerlitz in early December. Austerlitz led to the expulsion of Russian troops from Central Europe and the humiliation of Austria, which signed the Treaty of Pressburg on 26 December.

Fourth Coalition (1806–1807)

Austerlitz incited a major shift in the European balance of power. Prussia felt threatened about her security in the region and, alongside Russia, went to war against France as part of the Fourth Coalition in 1806. One hundred and eighty thousand French troops invaded Prussia in the fall of 1806 through the Thuringian Forest, unaware of where the Prussians were, and hugged the right bank of the Saale river and the left of the Elster.[11] The decisive actions took place on 14 October: with an army of 90,000, Napoleon crushed Hohenlohe at Jena, but Davout, commander of the III Corps, outdid everyone when his 27,000 troops held off and defeated the 63,000 Prussians under Brunswick and King Frederick William III at the Battle of Auerstadt.[12] A vigorous French pursuit through Northern Germany finished off the remnants of the Prussian army. The French then invaded Poland, which had been partitioned among Prussia, Austria, and Russia in 1795, to meet the Russian forces that had not been able to save Prussia.

The Russian and French armies met in February 1807 at the savage and indecisive Battle of Eylau, which left behind between 30,000–50,000 casualties. Napoleon regrouped his forces after the battle and continued to pursue the Russians in upcoming months. The action in Poland finally culminated on 14 June 1807, when the French mauled their Russian opponents at the Battle of Friedland. The resulting Treaty of Tilsit in July ended two years of bloodshed and left France as the dominant power on the European continent. It also severely weakened Prussia and formed a Franco-Russian axis designed to resolve disputes among European nations.

Iberia Peninsula (1807–1809)

After the War of the Oranges, Portugal adopted a double policy. On the one hand John, Prince of Brazil, as regent of Portugal, signed the Treaty of Badajoz with France and Spain by which he assumed the duty to close the ports to British trade. On the other hand, not wanting to breach the Treaty of Windsor (1386) with Portugal's oldest ally, Britain, he allowed for such trade to continue and maintained secret diplomatic relations with them. However, after the Franco-Spanish defeat in the Battle of Trafalgar, John grew bold and officially resumed diplomatic and trade relations with Britain.

Unhappy with this change of policy of the Portuguese government, Napoleon sent an army to invade Portugal. On 17 October 1807, 24,000[13] French troops under General Junot crossed the Pyrenees with Spanish cooperation and headed towards Portugal to enforce Napoleon's Continental System. This was the first step in what would become the six-year-long Peninsular War, a struggle that sapped much of the French Empire's strength. Throughout the winter of 1808, French agents became increasingly involved in Spanish internal affairs, attempting to incite discord between members of the Spanish royal family. On 16 February 1808, secret French machinations finally materialised when Napoleon announced that he would intervene to mediate between the rival political factions in the Spanish royal family.[14] Marshal Murat led 120,000 troops into Spain and the French arrived in Madrid on 24 March,[15] where wild riots against the occupation erupted a few weeks later. The resistance to French aggression soon spread throughout the country. The shocking French defeat at the Battle of Bailén in July gave hope to Napoleon's enemies and partly persuaded the French emperor to intervene in person. A new French army commanded by Napoleon crossed the Ebro in autumn and dealt blow after blow to the opposing Spanish forces. Napoleon entered Madrid on 4 December with 80,000 troops.[16] He then unleashed his troops against Moore's British forces. The British were swiftly driven to the coast, and, after a last stand at the Battle of Corunna in January 1809, withdrew from Spain entirely.

Austria stands alone

Austria sought another confrontation with France to avenge the recent defeats, and the developments in Spain only encouraged its attitudes. Austria could not count on Russian support because the latter was at war with Britain, Sweden (which meant Austria could not count on Swedish support either), and the Ottoman Empire in 1809. Some in the government of Frederick William III of Prussia initially wanted to help Austria, but their hopes were dashed when Stein's correspondence with Austria, planning such a move, was intercepted by the French and resulted in Prussia being compelled to sign the crushing Convention of September 1808.[17] The British had been at war with the French Empire for six years. A report from the Austrian finance minister suggested that the treasury would run out of money by mid-1809 if the large army that the Austrians had formed since the Third Coalition remained mobilised. Although Charles warned that the Austrians were not ready for another showdown with Napoleon, a stance that landed him amidst the so-called "peace party", he did not want to see the army demobilised. On 8 February 1809, the advocates for war finally succeeded when the Imperial Government secretly decided to make war against France.

Austrian reforms

Austerlitz and the subsequent Treaty of Pressburg in 1805 indicated that the Austrian army needed reform. Napoleon had offered Charles the Austrian throne after Austerlitz, an act that aroused deep suspicion from Charles' brother, Austrian emperor Francis II. Even though Charles was allowed to spearhead the reforms of the Austrian army, Francis kept the Hofkriegsrat (Aulic Council), a military advisory board, to oversee the activities of Charles as supreme commander.[18]

In 1806, Charles issued a new guide for army and unit tactics. The main tactical innovation was the concept of the "mass", an anti-cavalry formation created by closing up the spacing between ranks.[18] However, Austrian commanders disliked the innovation and rarely used it unless directly supervised by Charles.[18] Following the failures at Ulm and Austerlitz, the Austrians went back to using the six-companies-per-battalion model, abandoning the four-company-per-battalion that had been introduced by Mack on the eve of war in 1805.[18] Problems persisted despite the reforms. The Austrians lacked sufficient skirmishers to successfully contend with their French counterparts, the cavalry was often sprinkled into individual units throughout the army, preventing the shock and hitting power evident in the French system, and even though Charles imitated the French corps command structure, leaders in the Austrian military establishment were often wary of taking the initiative, relying heavily on written orders and drawn-out planning before they came to a decision.[19]

Another reform was that Austria, having lost many officers, veteran and elite troops, and regulars, and unable to call on allies, embraced the Levée en masse used earlier by the French. By this time, the French were moving from the Levée en masse in favour of forming a regular army based on a core of battle-hardened and elite veterans. In a strange reversal of the earlier Napoleonic Wars, where Frenchmen with little experience and often pressed into service fought against the professional Austrian army, a massive amount of Austrian conscripts, with no experience and only basic training and equipment would be sent into the field against a highly trained, campaign-hardened, and well-equipped French Grande Armée.

Austrian preparations

Charles and the Aulic Council were divided about the strategy with which to attack the French. Charles wanted a major thrust from Bohemia designed to isolate the French forces in northern Germany and lead to a rapid decision.[20] The greater part of the Austrian army was already concentrated there, so it seemed like a natural operation.[20] The Aulic Council disagreed on account of the Danube River splitting the forces of Charles and his brother John.[20] They instead suggested that the main attack should be launched south of the Danube so as to maintain safer communications with Vienna.[20] In the end, they had their way, but not before precious time had been lost. The Austrian plan called for the Bohemian corps, the I under Bellegarde, consisting of 38,000 troops, and the II of 20,000 troops under Kollowrat, to attack Regensburg (Ratisbon) from the Bohemian mountains by way of Cham, the Austrian center and reserve, comprising 66,000 men of Hohenzollern's III, Rosenberg's IV, and Lichtenstein's I Reserve Corps, to advance on the same objective through Scharding, and the left wing, made up of the V of Archduke Louis, Hiller's VI, and Kienmayer's II Reserve Corps, a total of 61,000 men, to move forward toward Landshut and guard the flank.[21]

Congress of Erfurt (1808)

At Tilsit Napoleon had made Tsar Alexander of Russia an admirer, but by the time of the Erfurt Congress from September to October 1808 anti-French sentiment at the Russian court was beginning to threaten the newly forged alliance. Napoleon and his foreign minister Jean-Baptiste Nompère de Champagny sought to reaffirm the alliance once more in order to allow Napoleon to settle affairs in Spain, as well as prepare for the looming war with Austria. Working at cross-purposes to Napoleon was his former foreign minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord who had by this time come to the conclusion that Napoleon and his war policies were leading France to destruction, and who secretly advised Alexander to resist Napoleon's demands.

Out of the meetings came an agreement, the Erfurt Convention (in 14 articles,) calling upon Britain to cease its war against France, recognizing the Russian conquest of Finland from Sweden, and stating that in case of war with Austria, Russia should aid France "to the best of its ability."[22] The two emperors departed for their homelands on 14 October. Six months later, the expected war with Austria began, and Alexander barely lived up to his agreement, aiding France as little as possible (though in the resulting Treaty of Schönbrunn Russia did receive a portion of Austrian Polish territory, namely the district of Tarnopol, for at least maintaining neutrality). By 1810, due mainly to the economic pressures of enforcing the Continental System, both emperors were considering war with one another. Erfurt was the last meeting between the two leaders.

French preparations

Napoleon was not entirely certain about Austrian planning and intentions. He had just returned to Paris at the time (from his campaigns in Spain in winter 1808–09) and was instructing the main French field commander in southern Germany, Berthier, on planned deployments and concentrations for this likely new second front. His rough ideas about the possible upcoming campaign included the decision to make the Danube valley the main theatre of operations, as he had done in 1805, and to tie down any Austrian forces that might invade northern Italy by positioning some of his own forces that would be commanded by Eugène and Marmont.[23] Faulty intelligence gave Napoleon the impression that the main Austrian attack would come north of the Danube.[24] On 30 March, he wrote a letter to Berthier explaining his intention to mass around 140,000 troops in the vicinity of Regensburg (Ratisbon), far to the north of where the Austrians were planning to make their attack.[25] Napoleon also expected the Austrian offensive to commence no earlier than 15 April (it would in fact begin on 9 April) and his two contingency orders relayed to Berthier were based heavily on this supposition. These misconceptions about Austrian thinking left the French army poorly deployed when hostilities commenced.

Course of War

The war pitted a reformed Austrian army against a collection of French veterans and conscripts. With major engagements of the war lasting from April to July 1809, Napoleon achieved the quick victory that characterised his previous campaigns. However, the War of the Fifth Coalition would also mark the last time in which Napoleon and the French Empire would emerge as decisive victors.

Austria strikes first

In the early morning of 10 April, leading elements of the Austrian army crossed the Inn River and invaded Bavaria. Bad roads and freezing rain slowed the Austrian advance in the first week, but the opposing Bavarian forces gradually retreated. The Austrian attack occurred about a week before Napoleon's anticipations, and in his absence Berthier's role became all the more critical. Berthier (whose fortè was staff work) proved to be an insufficient field commander, a characteristic made worse by the fact that several messages from Paris were being delayed and misinterpreted when they finally arrived at headquarters.[26] Whereas Napoleon had written to Berthier that an Austrian attack before 15 April should be met by a general French concentration around Donauwörth and Augsburg, Berthier focused on a sentence that called for Davout to station his III Corps around Regensburg and ordered the Iron Marshal to move back to the city despite massive Austrian pressure.[26]

The Grande Armée d'Allemagne was now in a perilous position of two wings separated by 75 miles (121 km) and joined together by a thin cordon of Bavarian troops. Berthier, the French marshals, and the rank-and-file were all evidently frustrated at the seemingly pointless marches and counter marches.[27] On the 16th, the Austrian advance guard had beaten back the Bavarians near Landshut and had secured a good crossing place over the Isar by evening. Napoleon finally arrived in Donauwörth on the 17th after a furious trip from Paris. Charles congratulated himself on a successful opening to the campaign and planned to destroy Davout's and Lefebvre's isolated corps in a double-pincer manoeuvre. When Napoleon realised that significant Austrian forces were already over the Isar and were marching towards the Danube, he insisted that the entire French army deploy behind the Ilm River in a bataillon carré within 48 hours, all in hopes of undoing Berthier's mistakes and achieving a successful concentration.[28] His orders were unrealistic because he underestimated the number of Austrian troops that were heading for Davout; Napoleon believed Charles only had a single corps over the Isar, but in fact, the Austrians had five corps lumbering towards Regensburg, a grand total of 80,000 men.[28] Napoleon needed to do something quickly to save his left flank from collapsing.

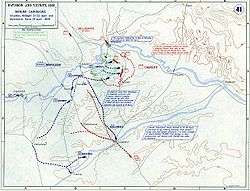

Landshut Maneuver

Davout anticipated the problems and withdrew his corps from Regensburg, leaving a garrison of only 2,000 for defence.[29] The northbound Austrian columns in the Kelheim–Abbach zone ran into the four French columns heading west towards Neustadt in the early hours of the 19th. The Austrian attacks were slow, uncoordinated, and easily repulsed by the experienced French III Corps. Napoleon knew there was fighting in Davout's sector and had already devised a new strategy that he hoped would beat the Austrians: while the Austrians attacked to the north, Masséna's corps, later augmented by Oudinot's forces, would strike southeast towards Freising and Landshut in hopes of rolling up the entire Austrian line and relieving the pressure on Davout.[30] Napoleon was reasonably confident that the joint corps of Davout and Lefebvre could pin the Austrians while his other forces swept the Austrian rear.

The attack began well as the central Austrian V Corps guarding Abensberg gave way to the French advance. Napoleon, however, was working under false assumptions that made his goals difficult to achieve.[31] Massena's advance towards Landshut required too much time, permitting Hiller to escape south over the Isar. The Danube bridge that provided easy access to Regensburg and the east bank had not been demolished, allowing the Austrians to transfer themselves across the river and rendering futile French hopes for the complete destruction of the enemy. On the 20th, the Austrians had suffered 10,000 casualties, lost 30 guns, 600 caissons, and 7,000 other vehicles, but were still a potent fighting force.[32] Later in the evening, Napoleon realised that the day's fighting had only involved two Austrian corps. Charles still had a good chance of escaping east over Straubing if he wished.

On the 21st, Napoleon received a dispatch from Davout that spoke of major engagements near Teugen-Hausen. Davout held his ground, and although Napoleon sent reinforcements, about 36,000 French troops had to face off against 75,000 Austrians.[33] When Napoleon finally learned that Charles was not withdrawing to the east, he realigned the Grande Armée's axis in an operation that became known as the Landshut Maneuver. All available French forces, except 20,000 troops under Bessieres that were chasing Hiller, now hurled themselves against Eckmühl in another bid to trap the Austrians and relieve their beleaguered comrades.[34] For 22 April, Charles left 40,000 troops under Rosenburg and Hohenzollern to attack Davout and Lefebvre while detaching two corps under Kollowrat and Lichtenstein to march for Abbach and gain undisputed control of the river bank.[34] At 1:30 pm, however, the sound of gunfire from the south could be heard—Napoleon had arrived. Davout immediately ordered an attack along the entire line despite numerical inferiority; the 10th Light Infantry Regiment successfully stormed the village of Leuchling and went on to capture the woods of Unter-Leuchling with horrific casualties.[35] Napoleon's reinforcements were soon crippling the Austrian left. The Battle of Eckmühl ended in a convincing French victory, and Charles decided to withdraw over the Danube towards Regensburg. Napoleon then launched Massena to capture Straubing to the east while the rest of the army pursued the escaping Austrians. The French managed to capture Regensburg after a heroic charge led by Marshal Lannes, but the vast majority of the Austrian army fled successfully to Bohemia. Napoleon then turned his attention south towards Vienna, fighting a series of actions against Hiller's forces, most famously, at the Battle of Ebersberg on 3 May. Ten days later, the Austrian capital fell for the second time in four years.

Aspern-Essling

On 16 May and 17, the main Austrian army under Charles arrived in the Marchfeld, a plain northeast of Vienna just across the Danube that often served as a training ground for Austrian military forces. Charles kept the bulk of his forces several miles away from the river bank in hopes of concentrating them at the point where Napoleon decided to cross. On the 20th, Charles learned from his observers on the Bissam hill that the French were building a bridge at Kaiser-Ebersdorf,[36] just southwest of the Lobau island, that led to the Marchfeld. On the 21st, Charles concluded that the French were crossing at Kaiser-Ebersdorf in strength and ordered a general advance for 98,000 troops and the accompanying 292 guns, which were organised into five columns.[37] The French bridgehead rested on two villages: Aspern to the west and Essling to the east. Napoleon had not expected to encounter opposition, and the bridges linking the French troops at Aspern-Essling to Lobau were not protected with palisades, making them highly vulnerable to Austrian barges that had been lighted on fire.[38]

The Battle of Aspern-Essling started at 2:30 pm on 21 May. The initial and poorly coordinated Austrian attacks against Aspern and the Gemeinde Au woods to the south failed completely, but Charles persisted. Eventually, the Austrians managed to capture the whole village but lost the eastern half. The Austrians did not attack Essling until 6 pm because the fourth and fifth columns had longer marching routes.[38] The French successfully repulsed the attacks against Essling throughout the 21st. Fighting commenced by 3 am on the 22nd, and four hours later the French had captured Aspern again. Napoleon now had 71,000 men and 152 guns on the other side of the river, but the French were still dangerously outnumbered.[39] Napoleon then launched a massive assault against the Austrian center designed to give enough time for the III Corps to cross and clinch the victory. Lannes advanced with three infantry divisions and travelled for a mile before the Austrians, inspired by the personal heroics of Charles with his rally of the Zach Infantry Regiment (No. 15), unleashed a hail of fire on the French that caused the latter to fall back.[40] At 9 am, the French bridge broke again. Charles launched another massive assault an hour later and captured Aspern for good, but still could not lay claim to Essling. A few hours later, however, the Austrians returned and took all of Essling except the staunchly defended granary. Napoleon replied by sending a part of the Imperial Guard under Jean Rapp, who audaciously disobeyed Napoleon's orders by attacking Essling and expelling all Austrian forces.[41] Charles then kept up a relentless artillery bombardment that counted Marshal Lannes as one of its many victims. Fighting diminished shortly afterwards, and the French pulled back all of their forces to Lobau. Charles had inflicted the first major defeat in Napoleon's military career.

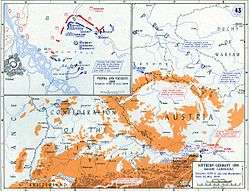

Wagram

After the defeat at Aspern-Essling, Napoleon took more than six weeks in planning and preparing for contingencies before he made another attempt at crossing the Danube.[42] The French brought in more troops, more guns, and instituted better defensive measures to ensure the success of the next crossing. From 30 June to the early days of July, the French recrossed the Danube in strength, no less than 188,000 troops marching across the Marchfeld towards the Austrians.[42] Immediate resistance to the French advance was restricted to the outpost divisions of Nordmann and Johann von Klenau; the main Habsburg army was stationed five miles (8 km) away, centred on the village of Wagram.[43] After a successful crossing, Napoleon ordered an attack along the entire line so as to prevent the Austrians from escaping during the night. Furious assaults by the "Terrible 57th" Infantry Regiment and the elite 10th Light Infantry Regiment against the village of Baumersdorf led to an almost immediate French victory, but ultimately, the Austrians did not budge and kept the French from pressing further. Incessant attacks by the heroic Austrian Vincent Chevaulegers' cavalry forced the 10th and the 57th to retreat, leaving the French with no gains. Further attacks to the left of the line by Eugène and MacDonald also produced nothing. Bernadotte's troops attacked later with equally disappointing results, and on the right Davout decided to disengage in the darkness of the night. The first day ended with the French on the Marchfeld but with little results to show for their efforts.

For 6 July, Charles planned a double-envelopment that would require a quick march from the forces of his brother John, then a few kilometres to the east of the battlefield. Napoleon's plan envisaged an envelopment of the Austrian left with Davout's III Corps while the rest of the army pinned the Austrian forces. Klenau's VI Corps, supported by Kollowrat's III, opened the fighting in the second day at 4 am with a crushing assault against the French left, forcing the latter to abandon both Aspern and Essling.[44] Meanwhile, a shocking development had occurred overnight. Bernadotte had unilaterally ordered his troops out of the key and central village of Aderklaa, citing heavy artillery shelling, an act that seriously compromised the entire French position.[44] Napoleon was livid and sent two divisions of Massena's corps supported by some cavalry to regain the critical village. After difficult fighting in the first phase, Massena sent in Molitor's reserve division, which slowly but surely grabbed all of Aderklaa back for the French, only to lose it again following fierce Austrian bombardments and counterattacks. To buy time for Davout's materialising assault, Napoleon sent 4,000 cuirassiers under Nansouty against the Austrian lines,[45] but their efforts led to nothing. To secure his center and his left, Napoleon formed a massive artillery battery of 112 guns that began pounding at the Austrians and tearing gaping holes through their lines.[46] As Davout's men were progressing against the Austrian left, Napoleon formed the three small divisions of MacDonald into a hollow, oblong shape that marched against the Austrian center. The lumbering phalanx was devastated by Austrian artillery but managed to break through the center, although the victory could not be exploited because there was no cavalry in the immediate area. Nevertheless, when Charles sized up the situation, he realised it was only a matter of time before the Austrian position broke completely and ordered a retreat toward Bohemia a few hours after noon. His brother John arrived on the battlefield at 4 pm, too late to have any impact, and accordingly ordered a retreat to Bohemia as well.

The French did not pursue the Austrians immediately because they were exhausted from two straight days of vicious fighting. After recuperating, they chased the Austrians and caught up with them at Znaim in mid-July. Here Charles signed an armistice with Napoleon and agreed to end the fighting. Military conflict between France and Austria was effectively ended, although a few more months of diplomatic wrangling were required to make the result official.

Other theatres

Italy and Dalmatia

In Italy, Archduke John went up against Napoleon's stepson Eugène. The Austrians beat back several bungled French assaults at the Battle of Sacile in April, causing Eugène to fall back on Verona and the Adige River, but Eugène regrouped and launched a more mature offensive that expelled the Austrians from Northern Italy again. By the time of Wagram, Eugène's forces had joined Napoleon's main army.[47] In Dalmatia, Marmont, under the nominal command of Eugène, was fighting against General Stoichewich. Marmont launched a mountain offensive on 30 April, but this was repulsed by the Grenzer troops.[48] Like Eugène, however, Marmont did not let an initial setback dictate the tempo of the conflict. He went back on the offensive and joined Napoleon at Wagram.

Poland

In the Duchy of Warsaw, Poniatowski defeated the Austrians at Raszyn on 19 April, prevented Austrian forces from crossing the Vistula river, and forced the Austrians to retreat from occupied Warsaw. Afterward, the Poles went on to invade Galicia, with some success, but the offensive quickly stalled with heavy casualties. The Austrians also won a few battles but were hampered by the presence of Russian troops whose intentions were unclear and that did not allow them to advance.[49] Eventually, the defeat of the main Austrian army at Wagram decided of the fate of the war.

After the Austrian invasion of the Duchy of Warsaw, Russia, bound by the treaty of alliance with France, reluctantly entered the war against Austria. The Russian army under the command of General Sergei Golitsyn crossed into Galicia on 3 June 1809. Golitsyin advanced as slowly as possible, with instructions to avoid any major confrontation with the Austrians. There were only minor skirmishes between the Russian and Austrian troops, with minimal losses. The Austrian and Russian commanders were in frequent correspondence and, in fact, shared some operational intelligence. A courteous letter sent by a Russian divisional commander, General Andrey Gorchakov, to Archduke Ferdinand was intercepted by the Poles, who sent an original to Emperor Napoleon and a copy to Tsar Alexander. As a result, Alexander had to remove Gorchakov from command. Furthermore, there were constant disagreements between Golitsyn and Poniatowski, with whom the Russians were supposed to cooperate in Galicia. As a result of the Treaty of Schönbrunn, Russia received the Galician district of Tarnopol.[50]

Germany

In Tyrol, Andreas Hofer led a rebellion against Bavarian rule and French domination that resulted in early isolated victories, but the uprising was suppressed after the French won at Wagram. Hofer was executed in 1810 by a firing squad.

In Saxony, a joint force of Austrians and Brunswickers under the command of General Kienmayer was far more successful, defeating a corps under the command of General Junot at the Battle of Gefrees. After taking the capital, Dresden, and pushing back an army under the command of Napoleon's brother, Jérôme Bonaparte, the Austrians were effectively in control of all of Saxony. But by this time, the main Austrian force had already been defeated at Wagram and the armistice of Znaim had been agreed.[51] The Duke of Brunswick however, refused to be bound by the armistice and led his corps on a fighting march right across Germany to the mouth of the River Weser, from where they sailed to England and entered British service.[52]

Holland

In the Kingdom of Holland, the British launched the Walcheren Campaign to relieve the pressure on the Austrians. The British force of over 39,000, a larger army than that serving in the Iberian Peninsula, landed at Walcheren on 30 July. However, by this time the Austrians had already lost the war. The Walcheren Campaign was characterised by little fighting but many casualties nevertheless, thanks to the popularly-dubbed "Walcheren Fever". Over 4,000 British troops were lost, and the rest withdrew in December 1809.[2]

Aftermath

Although France had not completely defeated Austria, the Treaty of Schönbrunn, signed on 14 October 1809, nevertheless imposed a heavy political toll on the Austrians. As a result of the treaty, France received Carinthia, Carniola, and the Adriatic ports, while Galicia was given to the Poles, the Salzburg area of the Tyrol went to the Bavarians, and Russia was ceded the district of Tarnopol. Austria lost over three million subjects, about 20% of her total population. Emperor Francis also agreed to pay an indemnity equivalent to almost 85 million francs, gave recognition to Napoleon's brother Joseph as the King of Spain, and reaffirmed the exclusion of British trade from his remaining dominions..[5] The Austrian defeat paved the way for the marriage of Napoleon to the daughter of Emperor Francis, Marie Louise. Dangerously, Napoleon assumed that his marriage to Marie Louise would eliminate Austria as a future threat, but the Habsburgs were not as driven by familial ties as Napoleon thought.

The impact of the conflict was not all positive from the French perspective. The revolts in Tyrol and the Kingdom of Westphalia during the conflict were an indication that there was much discontent over French rule among the German population. Just a few days before the conclusion of the Treaty of Schönbrunn, an 18-year-old German named Friedrich Staps approached Napoleon during an army review and attempted to stab the emperor, but he was intercepted in the nick of time by General Rapp.[53] The emerging forces of German nationalism were too strongly rooted by this time, and the War of the Fifth Coalition played an important role in nurturing their development.[53] By 1813, when the Sixth Coalition was fighting the French for control of Central Europe, the German population was fiercely opposed to French rule and largely supported the Allies.

The war also undermined French military superiority and the Napoleonic image. The Battle of Aspern-Essling was the first major defeat in Napoleon's career and was warmly greeted by much of Europe. The Austrians had also shown that strategic insight and tactical ability were no longer a French monopoly.[54] The French themselves were actually suffering from tactical shortcomings; the decline in tactical skill of the French infantry led to increasingly heavy columns of foot soldiers eschewing all manoeuvre and relying on sheer weight of numbers to break through, a development best emphasised by MacDonald's attack at Wagram.[54] The Grande Armée lost its qualitative edge partly because raw conscripts replaced many of the veterans of Austerlitz and Jena, eroding tactical flexibility.[55] Additionally, Napoleon's armies were more and more composed of non-French contingents, undermining morale.[55] Although Napoleon manoeuvred with customary brilliance, as evidenced by overturning the awful initial French position, the growing size of his armies stretched even his impressive mental faculties.[55] The scale of warfare grew too large for even Napoleon to fully cope with, a lesson that would be brutally repeated during the invasion of Russia in 1812.[55]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Chandler p. 673. Austria sent about 100,000 troops to attack Italy, 40,000 to protect Galicia, and held 200,000 men and 500 guns, organized into six line and two reserve corps, around the Danube valley for the main operations.

- 1 2 The British Expeditionary Force to Walcheren: 1809 The Napoleon Series, Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- ↑ David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon. p. 670.

- 1 2 Todd Fisher & Gregory Fremont-Barnes, The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. p. 144.

- 1 2 David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon. p. 732.

- ↑ Chandler p. 304.

- ↑ Chandler p. 328. The Baltic was dominated by Russia, a situation with which Britain was uncomfortable as the region provided valuable commodities like timber, tar, and hemp, crucial supplies to Britain's Empire. Additionally, Britain supported the Ottoman Empire against Russian incursions towards the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, French territorial rearrangements in Germany occurred without Russian consultation and Napoleon's annexations in the Po valley increasingly strained relations between the two.

- ↑ Chandler p. 331.

- ↑ Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 108.

- 1 2 Andrew Uffindell, Great Generals of the Napoleonic Wars. p. 15.

- ↑ David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon. p. 469.

- ↑ Chandler pp. 479–502.

- ↑ Todd Fisher & Gregory Fremont-Barnes, The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. p. 197.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes pp. 198–99.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 199.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 205.

- ↑ Napoleon – Felix Markham, p. 179

- 1 2 3 4 Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 108.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes pp. 108–9.

- 1 2 3 4 David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon. p. 676.

- ↑ Chandler pp. 676–77.

- ↑ "The Erfurt Convention 1808". Napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ Chandler p. 671.

- ↑ Chandler p. 672.

- ↑ Chandler p. 673.

- 1 2 Chandler pp. 678–79.

- ↑ Chandler p. 679. At midnight on 16 April, Berthier wrote the following to Napoleon: "In this position of affairs, I greatly desire the arrival of your Majesty, in order to avoid the orders and countermands which circumstances as well as the directives and instructions of your Majesty necessary entail."

- 1 2 Chandler p. 681.

- ↑ Chandler p. 682.

- ↑ Chandler p. 683.

- ↑ Chandler p. 686.

- ↑ Chandler p. 687.

- ↑ Chandler p. 689.

- 1 2 Chandler p. 690.

- ↑ Chandler p. 691.

- ↑ Andrew Uffindell, Great Generals of the Napoleonic Wars. p. 174.

- ↑ Uffindell, p. 175.

- 1 2 Uffindell, p. 177.

- ↑ Uffindell, p. 178.

- ↑ Uffindell, pp. 178–79.

- ↑ Uffindell, p. 179.

- 1 2 David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon. p. 708.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 134.

- 1 2 Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 139.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 141.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 142.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 122.

- ↑ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 123.

- ↑ 1809: thunder on the Danube, Jack Gill

- ↑ Mikaberidze pp. 4–22.

- ↑ F. Loraine Petre, Napoleon and the Archduke Charles. p. 318.

- ↑ Haythornthwaite p.147

- 1 2 Chandler p. 736.

- 1 2 Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 115.

- 1 2 3 4 Brooks (editor) p. 114.

References

- Brooks, Richard, ed. (2000). Atlas of World Military History. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7607-2025-8.

- Chandler, David G. (1995). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-02-523660-1.

- Fisher, Todd; Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2004). The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-831-6.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J (1990). The Napoleonic Source Book. London: Guild Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85409-287-8.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). "Non-Belligerent Belligerent Russia and the Franco-Austrian War of 1809". Napoleonica. La Revue. 1 (10): 4–22. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- Petre, F. Loraine (2003). Napoleon and the Archduke Charles. Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7385-2.

- Uffindell, Andrew (2003). Great Generals of the Napoleonic Wars. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 1-86227-177-1.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to War of the Fifth Coalition. |

Maude, Frederic Natusch (1911). "Napoleonic Campaigns". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 212–236.

Maude, Frederic Natusch (1911). "Napoleonic Campaigns". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 212–236.- "Napoleonic Wars: Fifth Coalition Against Napoleon Bonaparte: Aspern-Essling, Wagram, Eckmuhl, Landshut, Abensberg". Napoleon Bonaparte. Retrieved 20 July 2015.