Nimba otter shrew

| Nimba otter shrew | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Afrosoricida |

| Family: | Tenrecidae |

| Genus: | Micropotamogale |

| Species: | M. lamottei |

| Binomial name | |

| Micropotamogale lamottei Heim de Balsac, 1954 | |

| |

| Nimba otter shrew range | |

The Nimba otter shrew (Micropotamogale lamottei) is a dwarf otter shrew and belongs to the mammal family Tenrecidae. Tenrics have been found throughout mainland Africa and Madagascar; however, its subfamily Potamogalinae are the shrew-like creatures found in sub-Saharan Africa. This species belongs to the genus Micropotamogale, literally meaning "dwarf shrew". It is native to the Mount Nimba which rests along the border of Liberia, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) in West Africa.

Description

The Nimba otter shrew is a small bodied mammal. Weighing only about 125 grams (4.5 ounces) it has a body length of 6-9 inches(15–22 cm.) with 1/4 to 1/3 of its body size being its tail. It has been described as a "miniature sea otter with a rat tail".[2] Its pelage is long, hiding its ears and eyes, and almost always universally colored (usually brown, but black and gray otter shrews have been spotted).[3]

Evolution and Life History

Nimba otter shrew is solely classified as a member of Tenrecidae, with African hedgehogs and rodents, based on morphological structures. New breakthroughs in genetic testing are finding that it does belong in this family and subfamily Potamogalinae.[4] Unfortunately, due to heavy mining operations for iron ore in Mount Nimba, the fossil record is all but destroyed in that area. It is also difficult for scientists to gain access because the mountain crosses the borders of three different countries.[5]

Ecology and behavior

Nimba otter shrew is nocturnal and semiaquatic.[3] It resides in soft soils around creek beds and streams. The Nimba otter shrew is a solitary creature and has only been seen with other shrews during mating seasons and when a mother is nursing newly born young.[6] The breeding pattern of the Nimba otter shrew is also unknown, but believed to be polygamous; as there have been no witnessed accounts of breeding in the wild and the Nimba otter shrew will not mate in captivity.[7]

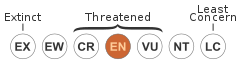

Conservation status

The IUCN had listed the Nimba otter shrew as endangered in 1990, and it has remained as such since the initial listing.[1] The species is confined to an area less than 5,000 square km on Mount Nimba, which is currently fragmented due to mining and wetland rice agriculture. The mining operations also produce runoff into the creeks and streambeds that is highly toxic.[7] The current population is decreasing at a rate of 1 per 10 square km (almost 500 otter shrews per year).[1] Although an exact number is unknown at this time, there is believed to be less than several hundred in captivity and 2500-3500 in the wild. At this rate the Nimba otter shrew will be extinct between 2017 and 2020.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 Vogel, P.; Afrotheria Specialist Group (2008). "Micropotamogale lamottei". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ↑ Kuhn, H (1971). "An Adult Female Micropotamogale lamottei". Journal of Mammalogy. 52 (2): 477. doi:10.2307/1378706. JSTOR 1378706.

- 1 2 David Burnie & Don E. Wilson (eds), ed. (2005-09-19). Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife (1st paperback ed.). Dorling Kindersley. p. 104. ISBN 0-7566-1634-4.

- ↑ van Dijk, M.O.; O. Madsen; F. Catzeflis; M. Stanhope; W. de Jong; M. Pagel (2011). "Protein sequence signatures support the African clade of mammals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (1): 188–193. doi:10.1073/pnas.250216797. PMC 14566

. PMID 11114173.

. PMID 11114173. - ↑ Africa Confidential (July 2000). "Africa Confidential. Volume 41 Number 15. Published 21 July 2000". Africa Confidential. 41 (15): 1–8. doi:10.1111/1467-6338.00090.

- ↑ Stephan, H; H. Kuhn (1954). "The Brain of Micropotamogale lamottei". Heim de Balsac. 47: 129–142.

- 1 2 Amori, G.; F. Chiozza; C. Rondinini; L. Luiselli (2011). "Country-based patterns of total species richness, endemicity, and threatened species richness in African rodents and insectivores". Biodiversity and Conservation. 20 (6): 1225–1237. doi:10.1007/s10531-011-0024-1.

- ↑ Amori, G.; S. Masciola; J. Saarto; S. Gippoliti; C. Rondinini; F. Chiozza; L. Luiselli (2012). "Spatial turnover and knowledge gap of Arican small mammals: using country checklists as a conservation tool". Biodiversity and Conservation. 21 (7): 1755–1793. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0275-5.