Gil Hodges

| Gil Hodges | |||

|---|---|---|---|

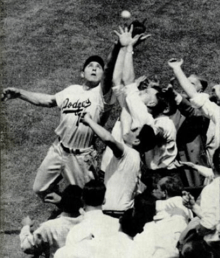

Hodges in 1958-59 | |||

| First baseman / Manager | |||

|

Born: April 4, 1924 Princeton, Indiana | |||

|

Died: April 2, 1972 (aged 47) West Palm Beach, Florida | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| October 3, 1943, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| May 5, 1963, for the New York Mets | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .273 | ||

| Home runs | 370 | ||

| Runs batted in | 1,274 | ||

| Managerial record | 650–753 | ||

| Winning % | .463 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

As player As manager | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

Gilbert Ray Hodges, ne Hodge[1] (April 4, 1924 – April 2, 1972) was an American Major League Baseball (MLB) first baseman and manager who played most of his 18-year career for the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers. He was inducted into the New York Mets Hall of Fame in 1982.

Hodges is generally considered to be the best defensive first baseman in the 1950s. He was an All-Star for eight seasons and a Gold Glove Award winner for three consecutive seasons. Hodges and Duke Snider are the only players to have the most home runs or runs batted in together during the decade with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Hodges was the National League (NL) leader in double plays four times and in putouts, assists and fielding percentage three times each. He ranked second in NL history with 1,281 assists and 1,614 double plays when his career ended, and was among the league's career leaders in games (6th, 1,908) and total chances (10th, 16,751) at first base.

Hodges also managed the New York Mets to the 1969 World Series title, one of the greatest upsets in Fall Classic history.[2]

In 2014, Hodges appeared for the second time as a candidate on the National Baseball Hall of Fame's Golden Era Committee election ballot[3] for possible Hall of Fame consideration in 2015. He and the other candidates all missed getting elected.[4] The Committee meets and votes on ten candidates selected from the 1947 to 1972 era every three years.[5]

Early years

Hodges was born in Princeton, Indiana, the son of coal miner Charles and his wife Irene, (nee Horstmeyer). He had an older brother, Robert, and a younger sister, Marjorie. The family moved to nearby Petersburg when Hodges was seven. He was a star four-sport athlete at Petersburg High School, earning a combined seven varsity letters in football, baseball, basketball and track. He declined a 1941 contract offer from the Detroit Tigers, instead attending Saint Joseph's College with the hope of eventually becoming a collegiate coach. Hodges spent two years (1941–1942 and 1942–1943) at St Joseph's, competing in baseball, basketball and briefly in football.[6]

He was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1943, and appeared in one game for the team as a third baseman that year. Hodges entered the United States Marine Corps during World War II after having participated in its Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) program at Saint Joseph's. He served in combat as an anti-aircraft gunner in the battles of Tinian and Okinawa, and received a Bronze Star Medal with Combat "V" for heroism under fire.

Following the war, Hodges also spent time completing course work at Oakland City University, near his hometown, playing basketball for the Mighty Oaks, joining the 1947–48 team after four games (1–3 record); they finished at 9–10.

Brooklyn Dodgers

He was discharged from the Marine Corps in 1946, and returned to the Dodgers organization as a catcher with the Newport News Dodgers of the Piedmont League, batting .278 in 129 games as they won the league championship; his teammates included first baseman and future film and television star Chuck Connors.

Called up to Brooklyn the following year, he played as a catcher in 1947, joining the team's nucleus of Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese and Carl Furillo, however, with the emergence of Roy Campanella behind the plate, Hodges was shifted by manager Leo Durocher to first base. Hodges' only appearance in the 1947 World Series against the New York Yankees was as a pinch hitter for pitcher Rex Barney in Game seven; he struck out.[7] As a rookie in 1948, he batted .249 with eleven home runs and seventy RBIs.

On June 25, 1949, he hit for the cycle on his way to his first of seven consecutive All-Star teams. For the season, his 115 RBI ranked fourth in the NL, and he tied Hack Wilson's 1932 club record for right-handed hitters with 23 home runs. Defensively, he led the NL in putouts (1,336), double plays (142) and fielding average (.995). Facing the Yankees again in the 1949 Series, he batted only .235 but drove in the sole run in Brooklyn's only victory, a 1–0 triumph in game two.[8] In game five, he hit a two out, three-run homer in the seventh to pull the Dodgers within 10–6, but struck out to end the game and the Series.[9]

On August 31, 1950 against the Boston Braves, he joined Lou Gehrig as only the second player since 1900 to hit four home runs in a game without the benefit of extra innings; he hit them against four different pitchers, with the first coming off Warren Spahn. He also had seventeen total bases in the game, tied for third in MLB history.

That year he also led the league in fielding (.994) and set a NL record with 159 double plays, breaking Frank McCormick's mark of 153 with the 1939 Cincinnati Reds; he broke his own record in 1951 with 171, a record which stood until Donn Clendenon had 182 for the 1966 Pittsburgh Pirates. He finished 1950 third in the league in both homers (32) and RBI (113), and came in eighth in the MVP voting. In 1951 he became the first member of the Dodgers to ever hit 40 home runs, breaking Babe Herman's 1930 mark of 35; Campanella hit 41 in 1953, but Hodges recaptured the record with 42 in 1954 before Snider eclipsed him again with 43 in 1956. His last home run of 1951 came on October 2 against the New York Giants, as the Dodgers tied the three-game NL playoff series at a game each with a 10-0 win; New York would take the pennant the next day on Bobby Thomson's "Shot Heard 'Round the World". Hodges also led the NL with 126 assists in 1951, and was second in HRs, third in runs (118) and total bases (307), fifth in slugging average (.527), and sixth in RBI (103).

Hodges was an eight-time All-Star, from 1949–55 and in 1957. With his last home run of 1952, he tied Dolph Camilli's Dodger career record of 139, surpassing him in 1953; Snider moved ahead of Hodges in 1956. He again led the NL with 116 assists in the 1952 campaign, and was third in the league in home runs (32) and fourth in RBI (102) and slugging (.500).

A great fan favorite in Brooklyn, he was perhaps the only Dodgers regular never booed at their home park, Ebbets Field. Fans were very supportive even when Hodges suffered through one of the most famous slumps in baseball history: after going hitless in his last four regular-season games of 1952, during the 1952 World Series against the Yankees, Hodges went hitless in all seven games, finishing the Series 0-for-21 at the plate, and Brooklyn lost the series in seven games. When his slump continued into the following spring, fans reacted with countless letters and good-luck gifts, and one Brooklyn priest – Father Herbert Redmond of St. Francis Roman Catholic Church – told his flock: "It's far too hot for a homily. Keep the Commandments and say a prayer for Gil Hodges."[10] Hodges began hitting again soon afterward, and rarely struggled again in the World Series.

Hodges was involved in a blown call in the 1952 World Series. In the fifth game, Johnny Sain, batting for the Yankees in the 10th inning, grounded out, as ruled by first base umpire Art Passarella. The photograph of the play, however, shows Sain stepping on first base while Hodges, also with a foot on the bag, reaches for the ball, which was about a foot away from his glove. Baseball commissioner Ford Frick, an ex-newspaperman himself, refused to defend Passarella.

He ended 1953 with a .302 batting average, finishing fifth in the NL in RBI (122) and sixth in home runs (31). Against the Yankees in the 1953 Series, Hodges hit .364; he had three hits, including a homer in the 9-5 Game 1 loss, but the Dodgers again lost in six games. Under their new manager Walter Alston in 1954 Hodges set the team home run record with 42, hitting a career-high .304 and again leading the NL in putouts (1,381) and assists (132). He was second in the league to Ted Kluszewski in home runs and RBI (130), fifth in total bases (335) and sixth in slugging (.579) and runs (106), and placed tenth in the MVP vote.

The Boys of Summer

The 1955 season saw Hodges' regular-season production decline to a .289 average, 27 HRs and 102 RBI. Facing the Yankees in the World Series for the fifth time, he was 1-for-12 in the first three games before coming around. In Game 4, Hodges hit a two-run homer in the fourth inning to put Brooklyn ahead, 4–3, and later had an RBI single as they held off the Yankees, 8–5; scoring the first run in his Dodgers 5-3 win in Game 5. In Game 7, he drove in Campanella with two out in the fourth for a 1–0 lead, and added a sacrifice fly to score Reese with one out in the sixth. Johnny Podres scattered eight New York hits, and when Reese threw Elston Howard's grounder to Hodges for the final out, Brooklyn had a 2–0 win and their first World Series title in franchise history, and only one in Brooklyn.

In 1956, Hodges had 32 home runs and 87 RBI as Brooklyn won the pennant again, and once more met the Yankees in the World Series. In the third inning of Game 1 he hit a three-run homer to put Brooklyn ahead, 5–2, as they went on to a 6-3 win; he had three hits and four RBI in Game 2's 13–8 slugfest, scoring to give the Dodgers a 7–6 lead in the third and doubling in two runs each in the fourth and fifth innings for an 11–7 lead. In Game 5 Hodges struck out, flied to center and lined to third base in Yankee Don Larsen's perfect game, as Brooklyn went on to lose in seven games.

In 1957 Hodges set the NL record for career grand slams, breaking the mark of 12 shared by Rogers Hornsby and Ralph Kiner; his final total of 14 was tied by Hank Aaron and Willie McCovey in 1972, and broken by Aaron in 1974. He finished seventh in the NL with a .299 batting average and fifth with 98 RBI, and leading the league with 1,317 putouts. He was also among the NL's top ten players in HRs (27), hits (173), runs (94), triples (7), slugging (.511) and total bases (296); in late September, he drove in the last Dodgers run ever at Ebbets Field, and the last run in Brooklyn history. Hodges was named to his last All-Star team, and placed seventh in the MVP balloting.

Los Angeles Dodgers

After the Dodgers relocated to Los Angeles, on April 23, 1958 Hodges became the seventh player to hit 300 home runs in the NL, connecting off Dick Drott of the Chicago Cubs. That year he also tied a post-1900 record by leading the league in double plays (134) for the fourth time, equaling Frank McCormick and Ted Kluszewski; Donn Clendenon eventually broke the record in 1968. Hodges' totals were 22 HRs and 64 RBI as the Dodgers finished in seventh place in their first season in California. Also in 1958, he broke Dolph Camilli's NL record of 923 career strikeouts.

In 1959, the Dodgers captured another NL title, with Hodges contributing 25 HRs and 80 RBI and hitting .276, coming in seventh in the league with a .513 slugging mark; he also led the NL with a .992 fielding average. He batted .391 in the 1959 World Series against the Chicago White Sox (his first against a team other than the Yankees), with his solo home run in the eighth inning of Game 4 giving the Dodgers a 5–4 win, as they triumphed in six games for another Series championship.

In 1960, Hodges broke Kiner's NL record for right-handed hitters of 351 career home runs, and appeared on the TV program Home Run Derby. In his last season with the Dodgers in 1961, he became the team's career RBI leader with 1,254, passing Zack Wheat; Snider moved ahead of him the following year. Hodges received the first three Rawlings Gold Glove Awards presented, from 1957 to 1959.

Return to New York

After being chosen in the 1961 MLB Expansion Draft, Hodges was one of the original 1962 Mets and despite knee problems was persuaded to continue his playing career in New York, hitting the first home run in franchise history. By the end of the year, in which he played only 54 games, he ranked tenth in MLB history with 370 HRs – second to only Jimmie Foxx among right-handed hitters. He also held the National League (NL) record for career home runs by a right-handed hitter from 1960 to 1963, and held the NL record for career grand slams from 1957 to 1974.[11]

Managerial career

After 11 games with the Mets in 1963, during which he batted .227 with no homers and was plagued by injuries, he was traded to the Washington Senators in late May for outfielder Jimmy Piersall so that he could replace Mickey Vernon as Washington's manager. Hodges immediately announced his retirement from playing in order to clearly focus on his new position. The Giants' Willie Mays had passed him weeks earlier on April 19 to become the NL's home run leader among right-handed hitters; Hodges' last game had been on May 5 in a doubleheader hosting the Giants (who had moved to San Francisco in 1958).

Hodges managed the Senators through 1967, and although they improved in each season they never achieved a winning record. One of the most notable incidents in his career occurred in the summer of 1965, when pitcher Ryne Duren – reaching the end of his career and sinking into alcoholism – walked onto a bridge with intentions of suicide; his manager talked him away from the edge. In 1968 Hodges was brought back to manage the perennially woeful Mets, and while the team only posted a 73–89 record it was nonetheless the best mark in their seven years of existence up to that point. In 1969, he led the "Miracle Mets" to the World Series championship, defeating the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles; after losing Game 1, they came back for four straight victories, including two by 2–1 scores. Finishing higher than ninth place for the first time, the Mets became not only the first expansion team to win a World Series, but also the first team ever to win the Fall Classic after finishing at least 15 games under .500 the previous year. Hodges was named The Sporting News' Manager of the Year, in skillfully platooning his players, utilizing everyone in the dugout, keeping everyone fresh.

In the third inning of the second game of a July 30 doubleheader against the Houston Astros, after scoring 11 runs in the ninth inning of the first game, the Astros were in the midst of a ten-run third inning, hitting a number of line drives to left field. When the Mets' star left fielder Cleon Jones failed to hustle after a ball hit to the outfield, Hodges removed him from the game, but rather than simply signal from the dugout for Jones to come out, or delegate the job to one of his coaches, Hodges left the dugout and slowly, deliberately, walked all the way out to left field to remove Jones, and walked him back to the dugout, which was a resounding message to the whole team. For the rest of that season, Jones never failed again to hustle. Kiner retold that story dozens of times during Mets broadcasts, both as a tribute to Hodges, and as an illustration of his quiet but disciplined character.

Death and impact

On the afternoon of April 2, 1972, Hodges was in West Palm Beach, Florida completing a round of golf with Mets coaches Joe Pignatano, Rube Walker and Eddie Yost when he collapsed en route to his motel room at the Ramada Inn across the street from Municipal Stadium, then the home of the Atlanta Braves and Montreal Expos. Hodges had suffered a sudden heart attack and was rushed to Good Samaritan Hospital where he died within 20 minutes of arrival.[12] Pignatano later recalled Hodges falling backwards and hitting his head on the sidewalk with a "sickening knock", bleeding profusely and turning blue.[13] Pignatano said "I put my hand under Gil's head, but before you knew it, the blood stopped. I knew he was dead. He died in my arms."[13] A lifelong chain smoker, Hodges had suffered a minor heart attack during a September 1968 game.[14]

The entire baseball community was horribly shocked and totally devastated at the sudden loss of one of baseball's most beloved players. A symbol of Brooklyn, many former teammates grieved at the loss of Hodges. Jackie Robinson, himself ill with heart disease and diabetes, told the Associated Press, "He was the core of the Brooklyn Dodgers.[13] With this, and what's happened to Campy (Roy Campanella) and lot of other guys we played with, it scares you. I've been somewhat shocked by it all. I have tremendous feelings for Gil's family and kids." Robinson himself died of a heart attack only six months later on October 24, 1972 at age 53.[12]

Duke Snider said "Gil was a great player, but an even greater man."[13] "I'm sick", said Johnny Podres. "I've never known a finer man."[13] A crushed Carl Erskine said "Gil's death is like a bolt out of the blue."[13] Don Drysdale, who himself died in Montreal of a sudden heart attack in 1993 at age 56, wrote in his autobiography that Hodges' death "absolutely shattered me. I just flew apart. I didn't leave my apartment in Texas for three days. I didn't want to see anybody. I couldn't get myself to go to the funeral. It was like I'd lost a part of my family."[13]

The wake was held at Our Lady Help of Christians Church in Midwood, Brooklyn on April 4, what would have been Hodges' 48th birthday. It was later estimated approximately 10,000 mourners had attended.[13]

Television broadcaster Howard Cosell was one of the many attendees at the wake. According to Gil Hodges Jr., Cosell brought him into the back seat of a car, where Jackie Robinson had been crying hysterically. Robinson then held Hodges Jr. and said, "Next to my son's death, this is the worst day of my life."[13]

Hodges was survived by his wife, the former Joan Lombardi (born 1926 in Brooklyn), whom he had married on December 26, 1948, and their children Gil Jr. (born March 12, 1950), Irene, Cynthia and Barbara. He is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in East Flatbush, Brooklyn.

Yogi Berra succeeded him as manager, having been promoted on the day of the funeral.[13] The American flag flew at half-staff on Opening Day at Shea Stadium, while the Mets wore black armbands on their left arms during the entire 1972 season in honor of Hodges. On June 9, 1973, the Mets again honored Hodges by retiring his uniform number 14.[13]

Accomplishments

.jpg)

Hodges batted .273 in his career with a .487 slugging average, 1,921 hits, 1,274 RBI, 1,105 runs, 295 doubles and 63 stolen bases in 2,071 games. His 361 home runs with the Dodgers remain second in team history to Snider's 389. His 1,614 career double plays placed him behind only Charlie Grimm (1733) in NL history, and were a major league record for a right-handed fielding first baseman until Chris Chambliss surpassed him in 1984. His 1,281 career assists ranked second in league history to Fred Tenney's 1,363, and trailed only Ed Konetchy's 1,292 among all right-handed first basemen. Snider broke his NL record of 1,137 career strikeouts in 1964.

Hodges received New York City's highest civilian honor, the Bronze Medallion, in 1969. On April 4, 1978 (what would have been Hodges' 54th birthday), the Marine Parkway Bridge, connecting Marine Park, Brooklyn with Rockaway, Queens, was renamed the Marine Parkway–Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge in his memory.[13] Other Brooklyn locations named for him are a park on Carroll Street, a Little League field on Shell Road in Brooklyn, a section of Avenue L and P.S. 193. In addition, part of Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn is named Gil Hodges Way. A Brooklyn bowling alley, Gil Hodges Lanes, is also named after him. Hodges was also inducted into the New York Mets Hall of Fame in 1982.

In Indiana, the high school baseball stadium in his birthplace of Princeton and a bridge spanning the East Fork of the White River in northern Pike County on State Road 57 bear his name. In 2007, Hodges was inducted into the Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame.[15] A Petersburg Little League baseball team also bears his name, Hodges Dodgers.

Hall of Fame consideration

| |

| Gil Hodges's number 14 was retired by the New York Mets in 1973. |

There has been continuing controversy for decades over the fact Gil Hodges has not been elected to membership in the Baseball Hall of Fame.[16] He was considered to be one of the finest players of the 1950s,[13] and graduated to managerial success with the Mets. However, critics of his candidacy point out that despite his offensive prowess, he never led the National League in any offensive category such as home runs, RBI, or slugging average, and never came close to winning an MVP award.[16] Hodges' not having been voted a Most Valuable Player may have been based in part on his having had some of his best seasons (1950, 1954 and 1957) in years when the Dodgers did not win the pennant.[16] Another thing that has probably hurt his Hall of Fame candidacy was the fact he went hitless in the 1952 World Series, going 0 for 21 with just one run scored and one batted in. In addition, his career batting average of .273 was likely frowned on by many Hall of Fame voters in his early years of eligibility; at the time of his death, only five players had ever been elected by the Baseball Writers' Association of America with batting averages below .300 – all of them catchers or shortstops, and only one (Rabbit Maranville) who had an average lower than Hodges' or who had not won an MVP award. By the time his initial eligibility expired in 1983, the BBWAA had elected only two more players with averages below .274 – third basemen Eddie Mathews (.271), who hit over 500 HRs, leading the NL twice, and Brooks Robinson (.267), who won an MVP award and set numerous defensive records.

In Hodges' defense, however, it bears mentioning that numerous other players, including Mathews, Al Kaline, Billy Williams and Eddie Murray, have been elected to the Hall of Fame despite never having been voted Most Valuable Player. Others, most notably Tony Pérez and Barry Larkin, have been elected despite never having led their leagues in any important offensive category in a season. (Perez, like Hodges, also was never voted Most Valuable Player, and his overall career statistics are very similar to Hodges'.) While Hodges did post some of his best season performances in years in which the Dodgers failed to win the pennant, he was nevertheless a significant contributor for the Dodgers in the seasons in which they did win pennants, as well. His contributions to the Dodgers' successful 1949, 1953, 1955 and 1959 campaigns are particularly noteworthy. With regard to Hodges' 1952 World Series slump, several Hall of Fame honorees, among them Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Stan Musial and Ted Williams, also endured severe batting slumps in World Series play. More to the point, Hodges' failure in the 1952 World Series does not obscure his fine performances for the Dodgers in the other World Series they played during his tenure with the club. Hodges led the Dodger hitters in the 1953 World Series, posting a batting average of .364. Hodges' .304 mark in the 1956 Series earned him a tie with Duke Snider for the top Dodgers batting average, while his eight Series RBI were good enough for the outright lead among Dodgers hitters in that department. Hodges shared top hitting honors for all starting position players on both teams in the 1959 Fall Classic with Chicago's Ted Kluszewski, both first basemen hitting at a .391 clip. He also drove in both runs in the Dodgers' decisive 2-0 victory in the seventh game of the 1955 Series, which brought Brooklyn its first (and only) World Series title.

Hodges was the prototype of the modern slugging first baseman, and while the post-1961 expansion era has resulted in numerous players surpassing his home run and RBI totals, he remains the only one of the 21 players who had 300 or more home runs by the time of his retirement who has not yet been elected (all but Chuck Klein and Johnny Mize were elected by the BBWAA). Some observers have also suggested that his death in 1972 removed him from public consciousness, whereas other ballplayers – including numerous Dodger greats – were in the public eye for years afterward, receiving the exposure which assist in their election. He did, however, collect 3,010 votes cast by the BBWAA during his initial eligibility period from 1969 to 1983 – 2nd place for an unselected player, he was passed by Jack Morris in 2014 when he collected 351 votes to push his total to 3,324. Hodges who was regularly considered for selection by the Hall of Fame's Veterans Committee since 1987, falling one vote short of election in 1993, when no candidates were selected.

Golden Era candidate

In the years since Hodges' retirement, however, the Hall of Fame has refused admittance to many players with similar or even superior records.[16] In 2011, Hodges became a Golden Era candidate (1947 to 1972 era) for consideration to be elected to the Hall of Fame by the new Golden Era Committee (replaced the Veterans Committee in 2010) on December 5, 2011. The voting by the committee took place during the Hall of Fame's 2-day winter meeting in Dallas, Texas.[16] Ron Santo was the only one elected of the ten Golden Era candidates with 15 votes, Jim Kaat had 10 votes, and Hodges and Minnie Miñoso were tied with 9 votes. Hodges' next chance under the 16-member Golden Era Committee's electorates was on December 8, 2014, when the committee voted at the MLB Winter Meeting.[17] Hodges received only 3 votes, and none of the other eight player candidates on the ballot were elected to the Hall of Fame either, including Dick Allen and Tony Oliva, who both received 11 of the needed 12 votes for Hall of Fame induction in 2015.

Mural

A 52 ft.x16ft. mural was dedicated in Hodges' hometown of Petersburg, Indiana in 2009; it was painted by artist Randy Hedden and includes pictures of Hodges as Brooklyn Dodger, manager of the New York Mets, and batting at Ebbets Field. The mural, located at the intersection of state highways 61 and 57, is meant to "raise awareness of Hodges' absence from the Baseball Hall of Fame."[18]

See also

- List of lifetime home run leaders through history

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Gold Glove Award winners at first base

- Lou Gehrig Memorial Award

- List of Major League Baseball retired numbers

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- Hitting for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball single-game home run leaders

References

- ↑ "Current and Former Players with Note Regarding Their Names". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ↑ "Page 2's List for top upset in sports history". ESPN.

- ↑ http://baseballhall.org/hall-of-fame/2015-golden-era-committee-ballot

- ↑ National Baseball Hall of Fame, 12/8/2014, "Golden Era Announces Results" Retrieved April 23, 2015

- ↑ MLB.com, "No one elected to Hall of Fame by Golden Era Committee" Retrieved April 24, 2015

- ↑ Bill Robertson. "Gil Was Grid Hero, too... for One Day".

- ↑ "1947 World Series, Game Seven". Baseball-Reference.com. October 6, 1947.

- ↑ "1949 World Series, Game Two". Baseball-Reference.com. October 6, 1949.

- ↑ "1949 World Series, Game Five". Baseball-Reference.com. October 9, 1949.

- ↑ Oliphant, Thomas (2005). Praying For Gil Hodges. United States: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0-312-31761-1.

- ↑ "Today we visit a few giants". The New York Daily News. December 7, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- 1 2 "Gil Hodges Dies of Heart Attack". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. April 3, 1972. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Clavin, Tom; Danny Peary (2012). Gil Hodges: The Brooklyn Bums, the Miracle Mets, and the Extraordinary Life of a Baseball Legend. New York: New American Library. pp. 359–361, 370–375. ISBN 978-0-451-23586-2.

- ↑ Durso, Joseph (September 26, 1968). "Hodges, Stricken by Mild Heart Attack, Expected to Rejoin Mets by Spring". The New York Times. p. 65. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ Marine Corps Community Services: Gil Hodges

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bloom, Barry M. (November 3, 2011). "Santo, Hodges among 10 on Golden Era ballot". MLB.com. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ↑ Rogers, Phil (December 5, 2011). "Cubs icon Santo elected to Hall of Fame". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ↑ Ethridge, Tim (May 6, 2009). "Petersburg honors Gil Hodges with mural". The Courier Press. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

Books

- Roger Kahn, "The Boys of Summer" (1972)

- Milton J. Shapiro. The Gil Hodges Story (1960).

- Gil Hodges and Frank Slocum. The Game Of Baseball (1969).

- Marino Amaruso. Gil Hodges: The Quiet Man (1991).

- Tom Oliphant. Praying for Gil Hodges: A Memoir of the 1955 World Series and One Family's Love of the Brooklyn Dodgers (2005) ISBN 0-312-31761-1.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or The Baseball Cube, or Baseball-Reference (Minors), or The Ultimate Mets Database

- Gil Hodges managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Official website

- 2007 Hall of Fame candidate profile at the Wayback Machine (archived April 3, 2007)

- Gil Hodges at Find a Grave

| Achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Pat Seerey |

Batters with 4 home runs in one game August 31, 1950 |

Succeeded by Joe Adcock |