French Third Republic

| French Republic | ||||||||||||||

| République française | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Motto "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" (French) "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" | ||||||||||||||

| Anthem "La Marseillaise" | ||||||||||||||

France in 1939

| ||||||||||||||

France in September 1939 Dark blue: Metropolitan territory of the Republic Light blue: Colonies, mandates, and protectorates of France | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Paris | |||||||||||||

| Languages | French | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism, disestablished 1905 | |||||||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||||||||||

| President | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1871–1873 | Adolphe Thiers (first) | ||||||||||||

| • | 1932–1940 | Albert Lebrun (last) | ||||||||||||

| President of the Council of Ministers | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1870–1871 | Louis Jules Trochu | ||||||||||||

| • | 1940 | Philippe Pétain | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||||||||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||||||||||

| • | Lower house | Chamber of Deputies | ||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||

| • | Proclamation by Leon Gambetta | 4 September 1870 | ||||||||||||

| • | Vichy France established | 10 July 1940 | ||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||

| • | est. | 35,565,800 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | French Franc | |||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of France | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

The French Third Republic (French: La Troisième République, sometimes written as La IIIe République) was the system of government adopted in France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed, until 1940, when France's defeat by Nazi Germany in World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government in France. It came to an end on 10 July 1940.

The early days of the Third Republic were dominated by political disruptions caused by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, which the Republic continued to wage after the fall of Emperor Napoleon III in 1870. Harsh reparations exacted by the Prussians after the war resulted in the loss of the French regions of Alsace (in its entirety) and Lorraine (the northeastern part, i.e. present-day département de la Moselle), social upheaval, and the establishment of the Paris Commune. The early governments of the Third Republic considered re-establishing the monarchy, but confusion as to the nature of that monarchy and who should be awarded the throne caused those talks to stall. Thus, the Third Republic, which was originally intended as a provisional government, instead became the permanent government of France.

The French Constitutional Laws of 1875 defined the composition of the Third Republic. It consisted of a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate to form the legislative branch of government and a president to serve as head of state. Issues over the re-establishment of the monarchy dominated the tenures of the first two presidents, Adolphe Thiers and Patrice de MacMahon, but the growing support for the republican form of government in the French population and a series of republican presidents during the 1880s quashed all plans for a monarchical restoration.

The Third Republic established many French colonial possessions, including French Indochina, French Madagascar, French Polynesia, and large territories in West Africa during the Scramble for Africa, all of them acquired during the last two decades of the 19th century. The early years of the 20th century were dominated by the Democratic Republican Alliance, which was originally conceived as a centre-left political alliance, but over time became the main centre-right party. The period from the start of World War I to the late 1930s featured sharply polarized politics, between the Democratic Republican Alliance and the more Radical socialists. The government fell during the early years of World War II as the Germans occupied France and was replaced by the rival governments of Charles de Gaulle's Free France (La France libre) and Philippe Pétain's Vichy France (L'État français).

Adolphe Thiers called republicanism in the 1870s "the form of government that divides France least"; however, politics under the Third Republic were sharply polarized. On the left stood Reformist France, heir to the French Revolution. On the right stood conservative France, rooted in the peasantry, the Roman Catholic Church and the army.[1] In spite of France's sharply divided electorate and persistent attempts to overthrow it, the Third Republic endured for seventy years, which makes it the longest lasting system of government in France since the collapse of the Ancien Régime in 1789.

Politics

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 resulted in the defeat of France and the overthrow of Emperor Napoleon III and his Second French Empire. After Napoleon's capture by the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan (1 September 1870), Parisian deputies led by Léon Gambetta established the Government of National Defence as a provisional government on 4 September 1870. The deputies selected General Louis-Jules Trochu to serve as its president. This first government of the Third Republic ruled during the Siege of Paris (19 September 1870 – 28 January 1871). As Paris was cut off from the rest of unoccupied France, the Minister of War, Léon Gambetta, who succeeded in leaving Paris in a hot air balloon, established the headquarters of the provisional republican government in the city of Tours on the Loire river.

After the French surrender in January 1871, the provisional Government of National Defence disbanded, and national elections were called with the aim of creating a new French government. French territories occupied by Prussia at this time did not participate. The resulting conservative National Assembly elected Adolphe Thiers as head of a provisional government, nominally ("head of the executive branch of the Republic pending a decision on the institutions of France"). Due to the revolutionary and left-wing political climate that prevailed in the Parisian population, the right-wing government chose the royal palace of Versailles as its headquarters.

The new government negotiated a peace settlement with the newly proclaimed German Empire: the Treaty of Frankfurt signed on 10 May 1871. To prompt the Prussians to leave France, the government passed a variety of financial laws, such as the controversial Law of Maturities, to pay reparations. In Paris, resentment against the government built and from late March – May 1871, Paris workers and National Guards revolted and established the Paris Commune, which maintained a radical left-wing regime for two months until its bloody suppression by the Thiers government in May 1871. The following repression of the communards would have disastrous consequences for the labor movement.

Parliamentary monarchy

The French legislative election of 1871, held in the aftermath of the collapse of the regime of Napoleon III, resulted in a monarchist majority in the French National Assembly that was favourable to making a peace agreement with Prussia. The "Legitimists" in the National Assembly supported the candidacy of a descendant of King Charles X, the last monarch from the senior line of the Bourbon Dynasty, to assume the French throne: his grandson Henri, Comte de Chambord, alias "Henry V." The Orléanists supported a descendant of King Louis Philippe I, the cousin of Charles X who replaced him as the French monarch in 1830: his grandson Louis-Philippe, Comte de Paris. The Bonapartists were marginalized due to the defeat of Napoléon III and were unable to advance the candidacy of any member of his family, the Bonaparte family. Legitimists and Orléanists came to a compromise, eventually, whereby the childless Comte de Chambord would be recognised as king, with the Comte de Paris recognised as his heir. Consequently, in 1871 the throne was offered to the Comte de Chambord.[2]

Chambord believed the restored monarchy had to eliminate all traces of the Revolution (including most famously the Tricolor flag) in order to restore the unity between the monarchy and the nation, which the revolution had sundered. Compromise on this was impossible if the nation were to be made whole again. The general population, however, was unwilling to abandon the Tricolor flag. Monarchists therefore resigned themselves to wait for the death of the aging, childless Chambord, when the throne could be offered to his more liberal heir, the Comte de Paris. A "temporary" republican government was therefore established. Chambord lived on until 1883, but by that time, enthusiasm for a monarchy had faded, and the Comte de Paris was never offered the French throne.[3]

The Ordre Moral government

The term ordre moral ("moral order") was applied to the policies of the early governments of the Third Republic in reference to the bloody suppression of the Paris Commune, whose political and social innovations were viewed as morally degenerate by large conservative segments of the French population.[4]

In February 1875, a series of parliamentary acts established the constitutional laws of the new republic. At its head was a President of the Republic. A two-chamber parliament consisting of a directly-elected Chamber of Deputies and an indirectly-elected Senate was created, along with a ministry under the President of the Council (prime minister), who was nominally answerable to both the President of the Republic and the legislature. Throughout the 1870s, the issue of whether a monarchy should replace the republic dominated public debate.

On 16 May 1877, with public opinion swinging heavily in favour of a republic, the President of the Republic, Patrice de MacMahon, himself a monarchist, made one last desperate attempt to salvage the monarchical cause by dismissing the republican prime minister Jules Simon and appointing the monarchist leader Albert, duc de Broglie, to office. He then dissolved parliament and called a general election for the following October. If his hope had been to halt the move towards republicanism, it backfired spectacularly, with the president being accused of having staged a constitutional coup d'état known as le seize Mai ("the 16 May Crisis") after the date on which it happened. Indeed, it was not until Charles de Gaulle, 80 years later, that a President of France next unilaterally dissolved parliament.[5]

Republicans returned triumphantly after the October elections for the Chamber of Deputies. The prospect of a monarchical restoration died definitively after the republicans gained control of the Senate on 5 January 1879. MacMahon himself resigned on 30 January 1879, leaving a seriously weakened presidency in the hands of Jules Grévy.

The Opportunist Republicans

Following the 16 May crisis in 1877, Legitimists were pushed out of power, and the Republic was finally governed by republicans referred to as Opportunist Republicans for their support of moderate social and political changes in order to establish the new regime firmly. The Jules Ferry laws that made public education free, mandatory, and secular (laїque), were voted in 1881 and 1882, one of the first signs of the expanding civic powers of the Republic. From that time onward, public education was no longer under the exclusive control of the Catholic congregations.[6]

To discourage French monarchism as a serious political force, the French Crown Jewels were broken up and sold in 1885. Only a few crowns, their precious gems replaced by coloured glass, were kept.

Boulanger crisis

In 1889, the Republic was rocked by a sudden political crisis precipitated by General Georges Boulanger. An enormously popular general, he won a series of elections in which he would resign his seat in the Chamber of Deputies and run again in another district. At the apogee of his popularity in January 1889, he posed the threat of a coup d'état and the establishment of a dictatorship. With his base of support in the working districts of Paris and other cities, plus rural traditionalist Catholics and royalists, he promoted an aggressive nationalism aimed against Germany. The elections of September 1889 marked a decisive defeat for the Boulangists. They were defeated by the changes in the electoral laws that prevented Boulanger from running in multiple constituencies; by the government's aggressive opposition; and by the absence of the general himself, who placed himself in self-imposed exile to be with his mistress. The fall of Boulanger severely undermined the political strength of the conservative and royalist elements within France; they would not recover their strength until 1940.[7]

Revisionist scholars have argued that the Boulangist movement more often represented elements of the radical left rather than the extreme right. Their work is part of an emerging consensus that France's radical right was formed in part during the Dreyfus era by men who had been Boulangist partisans of the radical left a decade earlier.[8]

Panama scandal

The Panama scandals of 1892 involved the enormous cost of a failed attempt to build the Panama Canal. Due to disease, death, inefficiency, and widespread corruption, the Panama Canal Company handling the massive project went bankrupt, with millions in losses. It is regarded as the largest monetary corruption scandal of the 19th century. Close to a billion francs were lost when the French government took bribes to keep quiet about the Panama Canal Company's financial troubles.[9]

Laggard welfare state and public health

France was laggard behind Bismarckian Germany, as well as Great Britain, in developing the welfare state including a public health, unemployment insurance and a national old age pension plan. There was an accident insurance law for workers in 1898 and in 1910 the national pension plan started. Unlike Germany or Britain, the programs were much smaller – for example, pensions were a voluntary plan.[10] Smith finds French fears of national public assistance programs were grounded in a widespread disdain for the English Poor Law.[11] Tuberculosis was the most dreaded disease of the day, especially striking young people in their 20s. Germany set up vigorous measures of public hygiene and public sanatoria, but France let private physicians handle the problem, which left it with a much higher death rate.[12] The French medical profession jealously guarded its prerogatives, and public health activists were not as well organized or as influential as in Germany, Britain or the United States.[13][14] For example, there was a long battle over a public health law which began in the 1880s as a campaign to reorganize the nation's health services, to require the registration of infectious diseases, to mandate quarantines, and to improve the deficient health and housing legislation of 1850. However the reformers met opposition from bureaucrats, politicians, and physicians. Because it was so threatening to so many interests, the proposal was debated and postponed for 20 years before becoming law in 1902. Success finally came when the government realized that contagious diseases had a national security impact in weakening military recruits, and keeping the population growth rate well below Germany's.[15]

Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair was a major political scandal that convulsed France from 1894 until its resolution in 1906, and then had reverberations for decades more. The conduct of the affair has become a modern and universal symbol of injustice. It remains one of the most striking examples of a complex miscarriage of justice in which a central role was played by the press and public opinion. At issue was blatant anti-Semitism as practiced by the French Army and defended by conservatives and catholic traditionalists against secular centre-left, left and republican forces, including most Jews. In the end, the latter triumphed.[16][17]

The affair began in November 1894 with the conviction for treason of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent. He was sentenced to life imprisonment for communicating French military secrets to the German Embassy in Paris and sent to the penal colony at Devil's Island in French Guiana (nicknamed la guillotine sèche, the dry guillotine), where he spent almost five years.

Two years later, evidence came to light that identified a French Army major named Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy as the real spy. After high-ranking military officials suppressed the new evidence, a military court unanimously acquitted Esterhazy. In response, the Army brought up additional charges against Dreyfus based on false documents. Word of the military court's attempts to frame Dreyfus began to spread, chiefly owing to the polemic J'accuse, a vehement open letter published in a Paris newspaper in January 1898 by the notable writer Émile Zola. Activists put pressure on the government to re-open the case.

In 1899, Dreyfus was returned to France for another trial. The intense political and judicial scandal that ensued divided French society between those who supported Dreyfus (now called "Dreyfusards"), such as Anatole France, Henri Poincaré and Georges Clemenceau, and those who condemned him (the anti-Dreyfusards), such as Édouard Drumont, the director and publisher of the anti-Semitic newspaper La Libre Parole. The new trial resulted in another conviction and a 10-year sentence, but Dreyfus was given a pardon and set free. Eventually all the accusations against him were demonstrated to be baseless, and in 1906, Dreyfus was exonerated and re-instated as a major in the French Army.

From 1894 to 1906, the scandal divided France deeply and lastingly into two opposing camps: the pro-Army "anti-Dreyfusards" composed of conservatives, Catholic traditionalists and monarchists who generally lost the initiative to the anti-clerical, pro-republican "Dreyfusards", with strong support from intellectuals and teachers. It embittered French politics and facilitated the increasing influence of radical politicians on both sides of the political spectrum.

Social history

Newspapers

The democratic political structure was supported by the proliferation of politicized newspapers. The circulation of the daily press in Paris went from 1 million in 1870 to 5 million in 1910; it later reached 6 million in 1939. Advertising grew rapidly, providing a steady financial basis for publishing, but it did not cover all of the costs involved and had to be supplemented by secret subsidies from commercial interests that wanted favorable reporting. A new liberal press law of 1881 abandoned the restrictive practices that had been typical for a century. High-speed rotary Hoe presses, introduced in the 1860s, facilitated quick turnaround time and cheaper publication. New types of popular newspapers, especially Le Petit Journal, reached an audience more interested in diverse entertainment and gossip than hard news. It captured a quarter of the Parisian market and forced the rest to lower their prices. The main dailies employed their own journalists who competed for news flashes. All newspapers relied upon the Agence Havas (now Agence France-Presse), a telegraphic news service with a network of reporters and contracts with Reuters to provide world service. The staid old papers retained their loyal clientele because of their concentration on serious political issues.[18] While papers usually gave false circulation figures, Le Petit Provençal in 1913 probably had a daily circulation of about 100,000 and Le Petit Meridional had about 70,000. Advertising only filled 20% or so of the pages.[19]

The Roman Catholic Assumptionist order revolutionized pressure group media by its national newspaper La Croix. It vigorously advocated for traditional Catholicism while at the same time innovating with the most modern technology and distribution systems, with regional editions tailored to local taste. Secularists and Republicans recognized the newspaper as their greatest enemy, especially when it took the lead in attacking Dreyfus as a traitor and stirring up anti-Semitism. After Dreyfus was pardoned, the Radical government closed down the entire Assumptionist order and its newspaper in 1900.[20]

Banks secretly paid certain newspapers to promote particular financial interests and hide or cover up misbehavior. They also took payments for favorable notices in news articles of commercial products. Sometimes, a newspaper would blackmail a business by threatening to publish unfavorable information unless the business immediately started advertising in the paper. Foreign governments, especially Russia and Turkey, secretly paid the press hundreds of thousands of francs a year to guarantee favorable coverage of the bonds it was selling in Paris. When the real news was bad about Russia, as during its 1905 Revolution or during its war with Japan, it raised the ante to millions. During the World War, newspapers became more of a propaganda agency on behalf of the war effort and avoided critical commentary. They seldom reported the achievements of the Allies, crediting all the good news to the French army. In a word, the newspapers were not independent champions of the truth, but secretly paid advertisements for banking.[21]

The World War ended a golden era for the press. Their younger staff members were drafted, and male replacements could not be found (female journalists were not considered suitable.) Rail transportation was rationed and less paper and ink came in, and fewer copies could be shipped out. Inflation raised the price of newsprint, which was always in short supply. The cover price went up, circulation fell and many of the 242 dailies published outside Paris closed down. The government set up the Interministerial Press Commission to supervise the press closely. A separate agency imposed tight censorship that led to blank spaces where news reports or editorials were disallowed. The dailies sometimes were limited to only two pages instead of the usual four, leading one satirical paper to try to report the war news in the same spirit:

- War News. A half-zeppelin threw half its bombs on half-time combatants, resulting in one-quarter damaged. The zeppelin, halfways-attacked by a portion of half-anti aircraft guns, was half destroyed."[19]

Regional newspapers flourished after 1900. However the Parisian newspapers were largely stagnant after the war. The major postwar success story was Paris Soir, which lacked any political agenda and was dedicated to providing a mix of sensational reporting to aid circulation and serious articles to build prestige. By 1939, its circulation was over 1.7 million, double that of its nearest rival the tabloid Le Petit Parisien. In addition to its daily paper. Paris Soir sponsored a highly successful women's magazine Marie-Claire. Another magazine, Match, was modeled after the photojournalism of the American magazine Life.[22]

Modernization of the peasants

France was a rural nation, and the peasant farmer was the typical French citizen. In his seminal book Peasants Into Frenchmen (1976), historian Eugen Weber traced the modernization of French villages and argued that rural France went from backward and isolated to modern with a sense of national identity during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[23] He emphasized the roles of railroads, republican schools, and universal military conscription. He based his findings on school records, migration patterns, military service documents and economic trends. Weber argued that until 1900 or so a sense of French nationhood was weak in the provinces. Weber then looked at how the policies of the Third Republic created a sense of French nationality in rural areas. Weber's scholarship was widely praised, but was criticized by some who argued that a sense of Frenchness existed in the provinces before 1870.[24]

Consumerism and the city department store

.jpg)

Aristide Boucicaut founded Le Bon Marché in Paris in 1838, and by 1852 it offered a wide variety of goods in "departments inside one building."[25] Goods were sold at fixed prices, with guarantees that allowed exchanges and refunds. By the end of the 19th century, Georges Dufayel, a French credit merchant, had served up to three million customers and was affiliated with La Samaritaine, a large French department store established in 1870 by a former Bon Marché executive.[26]

The French gloried in the national prestige brought by the great Parisian stores.[27] The great writer Émile Zola (1840–1902) set his novel Au Bonheur des Dames (1882–83) in the typical department store. Zola represented it as a symbol of the new technology that was both improving society and devouring it. The novel describes merchandising, management techniques, marketing, and consumerism.[28]

The Grands Magasins Dufayel was a huge department store with inexpensive prices built in 1890 in the northern part of Paris, where it reached a very large new customer base in the working class. In a neighbourhood with few public spaces, it provided a consumer version of the public square. It educated workers to approach shopping as an exciting social activity, not just a routine exercise in obtaining necessities, just as the bourgeoisie did at the famous department stores in the central city. Like the bourgeois stores, it helped transform consumption from a business transaction into a direct relationship between consumer and sought-after goods. Its advertisements promised the opportunity to participate in the newest, most fashionable consumerism at reasonable cost. The latest technology was featured, such as cinemas and exhibits of inventions like X-ray machines (that could be used to fit shoes) and the gramophone.[29]

Increasingly after 1870, the stores' work force became feminized, opening up prestigious job opportunities for young women. Despite the low pay and long hours, they enjoyed the exciting complex interactions with the newest and most fashionable merchandise and upscale customers.[30]

French colonial empire

The Third Republic, in line with the imperialistic ethos of the day sweeping Europe, developed a French colonial empire. The largest and most important were in French North Africa and French Indochina. French administrators, soldiers, and missionaries were dedicated to bringing French civilization to the local populations of these colonies (the mission civilisatrice). Some French businessmen went overseas, but there were few permanent settlements. The Catholic Church became deeply involved. Its missionaries were unattached men committed to staying permanently, learning local languages and customs, and converting the natives to Christianity.[31]

France successfully integrated the colonies into its economic system. By 1939, one third of its exports went to its colonies; Paris businessmen invested heavily in agriculture, mining, and shipping. In Indochina, new plantations were opened for rubber and rice. In Algeria, land held by rich settlers rose from 1,600,000 hectares in 1890 to 2,700,000 hectares in 1940; combined with similar operations in Morocco and Tunisia, the result was that North African agriculture became one of the most efficient in the world. Metropolitan France was a captive market, so large landowners could borrow large sums in Paris to modernize agricultural techniques with tractors and mechanized equipment. The result was a dramatic increase in the export of wheat, corn, peaches, and olive oil. French Algeria became the fourth most important wine producer in the world.[32][33]

Opposition to colonial rule led to rebellions in Morocco in 1925, Syria in 1926, and Indochina in 1930, all of which the colonial army quickly suppressed.

The Radicals' republic

The most important party in France of the early 20th century in France was the Radical Party, founded in 1901 as the "Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party" ("Parti républicain, radical et radical-socialiste"). It was classically liberal in political orientation and opposed the monarchists and clerical elements on the one hand, and the Socialists on the other. Many members had been recruited by the Freemasons.[34] The Radicals were split between activists who called for state intervention to achieve economic and social equality and conservatives whose first priority was stability. The workers' demands for strikes threatened such stability and pushed many Radicals toward conservatism. It opposed women's suffrage for fear that women would vote for its opponents or for candidates endorsed by the Catholic Church.[35] It favored a progressive income tax, economic equality, expanded educational opportunities and cooperatives in domestic policy. In foreign policy, it favored a strong League of Nations after the war, and the maintenance of peace through compulsory arbitration, controlled disarmament, economic sanctions, and perhaps an international military force.[36]

Followers of Léon Gambetta, such as Raymond Poincaré, who would become President of the Council in the 1920s, created the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD), which became the main center-right party after World War I.[37]

Governing coalitions collapsed with regularity, rarely lasting more than a few months, as radicals, socialists, liberals, conservatives, republicans and monarchists all fought for control. Some historians argue that the collapses were not important because they reflected minor changes in coalitions of many parties that routinely lost and gained a few allies. Consequently, the change of governments could be seen as little more than a series of ministerial reshuffles, with many individuals carrying forward from one government to the next, often in the same posts.

Church and state

Throughout the lifetime of the Third Republic (1870–1940), there were battles over the status of the Catholic Church in France among the republicans, monarchists and the authoritarians (such as the Napoleonists). The French clergy and bishops were closely associated with the monarchists and many of its hierarchy were from noble families. Republicans were based in the anti-clerical middle class, who saw the Church's alliance with the monarchists as a political threat to republicanism, and a threat to the modern spirit of progress. The republicans detested the Church for its political and class affiliations; for them, the Church represented the Ancien Régime, a time in French history most republicans hoped was long behind them. The republicans were strengthened by Protestant and Jewish support. Numerous laws were passed to weaken the Catholic Church. In 1879, priests were excluded from the administrative committees of hospitals and boards of charity; in 1880, new measures were directed against the religious congregations; from 1880 to 1890 came the substitution of lay women for nuns in many hospitals; in 1882, the Ferry school laws were passed. Napoleon's Concordat of 1801 continued in operation, but in 1881, the government cut off salaries to priests it disliked.[38]

Republicans feared that religious orders in control of schools—especially the Jesuits and Assumptionists—indoctrinated anti-republicanism into children. Determined to root this out, republicans insisted they needed control of the schools for France to achieve economic and militaristic progress. (Republicans felt one of the primary reasons for the German victory in 1870 was their superior education system.)

The early anti-Catholic laws were largely the work of republican Jules Ferry in 1882. Religious instruction in all schools was forbidden, and religious orders were forbidden to teach in them. Funds were appropriated from religious schools to build more state schools. Later in the century, other laws passed by Ferry's successors further weakened the Church's position in French society. Civil marriage became compulsory, divorce was introduced, and chaplains were removed from the army.[39]

When Leo XIII became pope in 1878, he tried to calm Church-State relations. In 1884, he told French bishops not to act in a hostile manner toward the State ('Nobilissima Gallorum Gens'[40]). In 1892, he issued an encyclical advising French Catholics to rally to the Republic and defend the Church by participating in republican politics ('Au milieu des sollicitudes'[41]). This attempt at improving the relationship failed. Deep-rooted suspicions remained on both sides and were inflamed by the Dreyfus Affair (1894–1906). Catholics were for the most part anti-Dreyfusard. The Assumptionists published anti-Semitic and anti-republican articles in their journal La Croix. This infuriated republican politicians, who were eager to take revenge. Often they worked in alliance with Masonic lodges. The Waldeck-Rousseau Ministry (1899–1902) and the Combes Ministry (1902–05) fought with the Vatican over the appointment of bishops. Chaplains were removed from naval and military hospitals in the years 1903 and 1904, and soldiers were ordered not to frequent Catholic clubs in 1904.

Emile Combes, when elected Prime Minister in 1902, was determined to defeat Catholicism thoroughly. After only a short while in office, he closed down all parochial schools in France. Then he had parliament reject authorisation of all religious orders. This meant that all fifty-four orders in France were dissolved and about 20,000 members immediately left France, many for Spain.[42] In 1904, Émile Loubet, the president of France from 1899 to 1906, visited King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy in Rome, and Pope Pius X protested at this recognition of the Italian State. Combes reacted strongly and recalled his ambassador to the Holy See. Then, in 1905, a law was introduced that abrogated Napoleon's 1801 Concordat. Church and State were finally separated. All Church property was confiscated. Religious personnel were no longer paid by the State. Public worship was given over to associations of Catholic laymen who controlled access to churches. However, in practice, masses and rituals continued to be performed.

The Combes government worked with Masonic lodges to create a secret surveillance of all army officers to make sure that devout Catholics would not be promoted. Exposed as the Affaire Des Fiches, the scandal undermined support for the Combes government, and he resigned. It also undermined morale in the army, as officers realized that hostile spies examining their private lives were more important to their careers than their own professional accomplishments.[43]

In December 1905, the government of Maurice Rouvier introduced the French law on the separation of Church and State. This law was heavily supported by Combes, who had been strictly enforcing the 1901 voluntary association law and the 1904 law on religious congregations' freedom of teaching. On 10 February 1905, the Chamber declared that “the attitude of the Vatican” had rendered the separation of Church and State inevitable and the law of the separation of church and state was passed in December 1905. The Church was badly hurt and lost half its priests. In the long run, however, it gained autonomy; ever after, the State no longer had a voice in choosing bishops, thus Gallicanism was dead.[44]

Foreign policy

French foreign policy from 1871 to 1914 showed a dramatic transformation from a humiliated power with no friends and not much of an empire in 1871, to the centerpiece of the European alliance system in 1914, with a flourishing empire that was second in size only to Great Britain. Although religion was a hotly contested matter and domestic politics, the Catholic Church made missionary work and church building a specialty in the colonies. Most Frenchman ignored foreign policy; its issues were a low priority in politics. [45][46]

1871-1900

French foreign policy was based on a fear of Germany—whose larger size and fast-growing economy could not be matched—combined with a revanchism that demanded the return of Alsace and Lorraine.[47] At the same time, imperialism was a factor.[48] In the midst of the Scramble for Africa, French and British interest in Africa came into conflict. The most dangerous episode was the Fashoda Incident of 1898 when French troops tried to claim an area in the Southern Sudan, and a British force purporting to be acting in the interests of the Khedive of Egypt arrived. Under heavy pressure the French withdrew securing Anglo-Egyptian control over the area. The status quo was recognised by an agreement between the two states acknowledging British control over Egypt, while France became the dominant power in Morocco, but France suffered a humiliating defeat overall.[49]

The Suez Canal, initially built by the French, became a joint British-French project in 1875, as both saw it as vital to maintaining their influence and empires in Asia. In 1882, ongoing civil disturbances in Egypt prompted Britain to intervene, extending a hand to France. The government allowed Britain to take effective control of Egypt.[50]

France had colonies in Asia and looked for alliances and found in Japan a possible ally. At Japan's request Paris sent military missions in 1872–1880, in 1884–1889 and in 1918–1919 to help modernize the Japanese army. Conflicts with China over Indochina climaxed during the Sino-French War (1884–1885). Admiral Courbet destroyed the Chinese fleet anchored at Foochow. The treaty ending the war put France in a protectorate over northern and central Vietnam, which it divided into Tonkin and Annam.[51]

Under the leadership of expansionist Jules Ferry, the Third Republic greatly expanded the French colonial empire. Catholic missionaries played a major role. France acquired Indochina, Madagascar, vast territories in West Africa and Central Africa, and much of Polynesia.[52]

1900-1914

In an effort to isolate Germany, France went to great pains to woo Russia and Great Britain, first by means of the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, then the 1904 Entente Cordiale with Great Britain, and finally the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907 which became the Triple Entente. This alliance with Britain and Russia against Germany and Austria eventually led Russia and Britain to enter World War I as France's Allies.[53]

French foreign policy in the years leading up to the First World War was based largely on hostility to and fear of German power. France secured an alliance with the Russian Empire in 1894 after diplomatic talks between Germany and Russia had failed to produce any working agreement. The Franco-Russian Alliance served as the cornerstone of French foreign policy until 1917. A further link with Russia was provided by vast French investments and loans before 1914. In 1904, French foreign minister Théophile Delcassé negotiated the Entente Cordiale with Lord Lansdowne, the British Foreign Secretary, an agreement that ended a long period of Anglo-French tensions and hostility. The Entente Cordiale, which functioned as an informal Anglo-French alliance, was further strengthened by the First and Second Moroccan crises of 1905 and 1911, and by secret military and naval staff talks. Delcassé's rapprochement with Britain was controversial in France as Anglophobia was prominent around the start of the 20th century, sentiments that had been much reinforced by the Fashoda Incident of 1898, in which Britain and France had almost gone to war, and by the Boer War, in which French public opinion was very much on the side of Britain’s enemies.[54] Ultimately, the fear of German power was the link that bound Britain and France together.[55]

Preoccupied with internal problems, France paid little attention to foreign policy in the period between late 1912 and mid-1914, although it did extend military service to three years from two over strong Socialist objections in 1913.[56] The rapidly escalating Balkan crisis of July 1914 surprised France, and not much attention was given to conditions that led to the outbreak of World War I.[57]

First World War

France entered World War I because Russia and Germany were going to war, and France honored its treaty obligations to Russia.[58] Decisions were all made by senior officials, especially president Raymond Poincaré, Premier and Foreign Minister René Viviani, and the ambassador to Russia Maurice Paléologue. Not involved in the decision-making were military leaders, arms manufacturers, the newspapers, pressure groups, party leaders, or spokesman for French nationalism. [59]

Britain wanted to remain neutral but entered the war when the German army invaded Belgium on its way to Paris. The French victory at the Battle of the Marne in September 1914 ensured the failure of Germany's strategy to win quickly. It became a long and very bloody war of attrition, but France emerged on the winning side.

French intellectuals welcomed the war to avenge the humiliation of defeat and loss of territory in 1871. At the grass roots, Paul Déroulède's League of Patriots, a proto-fascist movement based in the lower middle class, had advocated a war of revenge since the 1880s.[60] The strong socialist movement had long opposed war and preparation for war. However, when its leader Jean Jaurès, a pacifist, was assassinated at the start of the war, the French socialist movement abandoned its anti-militarist positions and joined the national war effort. Prime Minister René Viviani called for unity in the form of a "Union sacrée" ("Sacred Union"), and in France there were few dissenters.[61]

A state of emergency was proclaimed and censorship imposed, leading to the creation in 1915 of the satirical newspaper Le Canard enchaîné to bypass the censorship. The economy was hurt by the German invasion of major industrial areas in the northeast. Although the occupied area in 1914 contained only 14% of France's industrial workers, it produced 58% of the steel and 40% of the coal.[62] In 1914, the government implemented a war economy with controls and rationing. By 1915, the war economy went into high gear, as millions of French women and colonial men replaced the civilian roles of many of the 3 million soldiers. Considerable assistance came with the influx of American food, money and raw materials in 1917. This war economy would have important reverberations after the war, as it would be a first breach of liberal theories of non-interventionism.[63] The damages caused by the war amounted to about 113% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of 1913, chiefly the destruction of productive capital and housing. The national debt rose from 66% of GDP in 1913 to 170% in 1919, reflecting the heavy use of bond issues to pay for the war. Inflation was severe, with the franc losing over half its value against the British pound.[64]

To uplift the French national spirit, many intellectuals began to fashion patriotic propaganda. The Union sacrée sought to draw the French people closer to the actual front and thus garner social, political, and economic support for the soldiers.[65]

After the French army successfully defended Paris in 1914, the conflict became one of trench warfare along the Western Front, with very high casualty rates. It became a war of attrition. Until spring of 1918, amazing as it seems, there were almost no territorial gains or losses for either side. Georges Clemenceau, whose ferocious energy and determination earned him the nickname le Tigre ("the Tiger"), led a coalition government after 1917 that was determined to defeat Germany. Meanwhile, large swaths of northeastern France fell under the brutal control of German occupiers.[66]

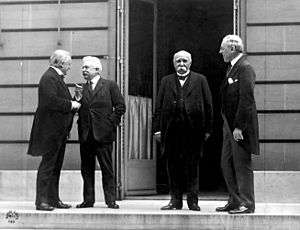

Peace

A quick change of fortunes in the late summer and autumn of 1918 saw the defeat of Germany in World War I. The most important factors that led to the surrender of Germany were its exhaustion after four years of fighting and the arrival of large numbers of troops from the United States beginning in the summer of 1918. Peace terms were imposed on Germany by the Big Four: Great Britain, France, the United States, and Italy. Clemenceau demanded the harshest terms and won most of them in the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Germany was largely disarmed and forced to take full responsibility for the war, meaning that it was expected to pay huge war reparations. France regained Alsace-Lorraine, and the German industrial Saar Basin, a coal and steel region, was occupied by France. The German African colonies, such as Kamerun, were partitioned between France and Britain. From the remains of the Ottoman Empire, Germany's ally during World War I that also collapsed at the end of the conflict, France acquired the Mandate of Syria and the Mandate of Lebanon.[67]

1919–1939

From 1919 to 1940, France was governed by two main groupings of political alliances. On the one hand, there was the right-center Bloc national led by Georges Clemenceau, Raymond Poincaré and Aristide Briand. The Bloc was supported by business and finance and was friendly toward the army and the Church. Its main goals were revenge against Germany, economic prosperity for French business and stability in domestic affairs. On the other hand, there was the left-center Cartel des gauches dominated by Édouard Herriot of the Radical Socialist party. Herriot's party was in fact neither radical nor socialist, rather it represented the interests of small business and the lower middle class. It was intensely anti-clerical and resisted the Catholic Church. The Cartel was occasionally willing to form a coalition with the Socialist Party. Anti-democratic groups, such as the Communists on the left and royalists on the right, played relatively minor roles.

The flow of reparations from Germany played a central role in strengthening French finances. The government began a large-scale reconstruction program to repair wartime damages, and was burdened with a very large public debt. Taxation policies were inefficient, with widespread evasion, and when the financial crisis grew worse in 1926, Poincaré levied new taxes, reformed the system of tax collection, and drastically reduced government spending to balance the budget and stabilize the franc. Holders of the national debt lost 80% of the face value of their bonds, but runaway inflation did not occur. From 1926 to 1929, the French economy prospered and manufacturing flourished.

Foreign observers in the 1920s noted the excesses of the French upper classes, but emphasized the rapid re-building of the regions of northeastern France that had seen warfare and occupation. They reported the improvement of financial markets, the brilliance of the post-war literature and the revival of public morale.[68]

Great Depression

The world economic crisis known as the Great Depression affected France a bit later than other countries, hitting around 1931.[69] While the GDP in the 1920s grew at the very strong rate of 4.43% per year, the 1930s rate fell to only 0.63%.[70] In comparison to countries such as the United States, Great Britain, and Germany, the depression was relatively mild: unemployment peaked under 5%, and the fall in production was at most 20% below the 1929 output. In addition, there was no banking crisis.[64][71]

Foreign policy

Foreign policy was of central interest to France during the inter-war period. The horrible devastation of the war, including the death of 1.5 million French soldiers, the devastation of much of the steel and coal regions, and the long-term costs for veterans, were always remembered. France demanded that Germany assume many of the costs incurred from the war through annual reparation payments. France enthusiastically joined the League of Nations in 1919, but felt betrayed by President Woodrow Wilson, when his promises that the United States would sign a defence treaty with France and join the League were rejected by the United States Congress. The main goal of French foreign policy was to preserve French power and neutralize the threat posed by Germany. When Germany fell behind in reparations payments in 1923, France seized the industrialized Ruhr region. The British Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, who viewed reparations as impossible to pay successfully, pressured French Premier Édouard Herriot into a series of concessions to Germany. In total, France received ₤1600 million from Germany before reparations ended in 1932, but France had to pay war debts to the United States, and thus the net gain was only about ₤600 million.[72]

France tried to create a web of defensive treaties against Germany with Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. There was little effort to build up the military strength or technological capabilities of these small allies, and they remained weak and divided among themselves. In the end, the alliances proved worthless. France also constructed a powerful defensive wall in the form of a network of fortresses along its German border. It was called the Maginot Line and was trusted to compensate for the heavy manpower losses of the First World War.[73]

The main goal of foreign policy was the diplomatic response to the demands of the French army in the 1920s and 1930s to form alliances against the German threat, especially with Britain and with smaller countries in central Europe.[74][75]

Appeasement was increasingly adopted as Germany grew stronger after 1933, for France suffered a stagnant economy, unrest in its colonies, and bitter internal political fighting. Appeasement, says historian Martin Thomas was not a coherent diplomatic strategy or a copying of the British.[76] France appeased Italy on the Ethiopia question because it could not afford to risk an alliance between Italy and Germany.[77] When Hitler sent troops into the Rhineland--the part of Germany where no troops were allowed--neither Paris nor London would risk war, and nothing was done.[78] The military alliance with Czechoslovakia was sacrificed at Hitler's demand when France and Britain agreed to his terms at Munich in 1938.[79][80]

The Popular Front

In 1920, the socialist movement split, with the majority forming the French Communist Party. The minority, led by Léon Blum, kept the name Socialist, and by 1932 greatly outnumbered the disorganized Communists. When Stalin told French Communists to collaborate with others on the left in 1934, a popular front was made possible with an emphasis on unity against fascism. In 1936, the Socialists and the Radicals formed a coalition, with Communist support, to complete it.[81]

The Popular Front's narrow victory in the elections of the spring of 1936 brought to power a government headed by the Socialists in alliance with the Radicals. The Communists supported its domestic policies, but did not take any seats in the cabinet. The prime minister was Léon Blum, a technocratic socialist who avoided making decisions. In two years in office, it focused on labor law changes sought by the trade unions, especially the mandatory 40-hour work week, down from 48 hours. All workers were given a two-week paid vacation. A collective bargaining law facilitated union growth; membership soared from 1,000,000 to 5,000,000 in one year, and workers' political strength was enhanced when the Communist and non-Communist unions joined together. The government nationalized the armaments industry and tried to seize control of the Bank of France in an effort to break the power of the richest 200 families in the country. Farmers received higher prices, and the government purchased surplus wheat, but farmers had to pay higher taxes. Wave after wave of strikes hit French industry in 1936. Wage rates went up 48%, but the work week was cut back by 17%, and the cost of living rose 46%, so there was little real gain to the average worker. The higher prices for French products resulted in a decline in overseas sales, which the government tried to neutralize by devaluing the franc, a measure that led to a reduction in the value of bonds and savings accounts. The overall result was significant damage to the French economy, and a lower rate of growth.[82]

Most historians judge the Popular Front a failure, although some call it a partial success. There is general agreement that it failed to live up to the expectations of the left.[83][84]

Politically, the Popular Front fell apart over Blum's refusal to intervene vigorously in the Spanish Civil War, as demanded by the Communists.[85] Culturally, the Popular Front forced the Communists to come to terms with elements of French society they had long ridiculed, such as patriotism, the veterans' sacrifice, the honor of being an army officer, the prestige of the bourgeois, and the leadership of the Socialist Party and the parliamentary Republic. Above all, the Communists portrayed themselves as French nationalists. Young Communists dressed in costumes from the revolutionary period and the scholars glorified the Jacobins as heroic predecessors.[86]

Conservatism

Historians have turned their attention to the right in the interwar period, looking at various categories of conservatives and Catholic groups as well as the far right fascist movement.[87] Conservative supporters of the old order were linked with the "haute bourgeoisie" (upper middle class), as well as nationalism, military power, the maintenance of the empire, and national security. The favorite enemy was the left, especially as represented by socialists. The conservatives were divided on foreign affairs. Several important conservative politicians sustained the journal Gringoire, foremost among them André Tardieu. The Revue des deux Mondes, with its prestigious past and sharp articles, was a major conservative organ.

Summer camps and youth groups were organized to promote conservative values in working-class families, and help them design a career path. The Croix de feu/Parti social français (CF/PSF) was especially active.[88]

Relations with Catholicism

France's republican government had long been strongly anti-clerical. The Law of Separation of Church and State in 1905 had expelled many religious orders, declared all Church buildings government property, and led to the closing of most Church schools. Since that time, Pope Benedict XV had sought a rapprochement, but it was not achieved until the reign of Pope Pius XI (1922–39). In the papal encyclical Maximam Gravissimamque (1924), many areas of dispute were tacitly settled and a bearable coexistence made possible.[89]

The Catholic Church expanded its social activities after 1920, especially by forming youth movements. For example, the largest organization of young working women was the Jeunesse Ouvrière Chrétienne/Féminine (JOC/F), founded in 1928 by the progressive social activist priest Joseph Cardijn. It encouraged young working women to adopt Catholic approaches to morality and to prepare for future roles as mothers at the same time as it promoted notions of spiritual equality and encouraged young women to take active, independent, and public roles in the present. The model of youth groups was expanded to reach adults in the Ligue ouvrière chrétienne féminine ("League of Working Christian Women") and the Mouvement populaire des familles.[90][91]

Catholics on the far right supported several shrill, but small, groupings that preached doctrines similar to fascism. The most influential was Action Française, founded in 1905 by the vitriolic author Charles Maurras. It was intensely nationalistic, anti-Semitic and reactionary, calling for a return to the monarchy and domination of the state by the Catholic Church. In 1926, Pope Pius XI condemned Action Française because the pope decided that it was folly for the French Church to continue to tie its fortunes to the unlikely dream of a monarchist restoration and distrusted the movement's tendency to defend the Catholic religion in merely utilitarian and nationalistic terms. Action Française never fully recovered from the denunciation, but it was active in the Vichy era.[92][93]

Downfall of the Third Republic

The looming threat to France of Nazi Germany was delayed at the Munich Conference of 1938. France and Great Britain abandoned Czechoslovakia and appeased the Germans by giving in to their demands concerning the acquisition of the Sudetenland (the portions of Czechoslovakia with German-speaking majorities). Intensive rearmament programs began in 1936 and were re-doubled in 1938, but they would only bear fruit in 1939 and 1940.[94]

Historians have debated two themes regarding the sudden collapse of the French government in 1940. One emphasizes a broad cultural and political interpretation, pointing to failures, internal dissension, and a sense of malaise that ran through all French society.[95] A second one blames the poor military planning by the French High Command. According to the British historian Julian Jackson, the Dyle Plan conceived by French General Maurice Gamelin was destined for failure, since it drastically miscalculated the ensuing attack by German Army Group B into central Belgium.[96] The Dyle Plan embodied the primary war plan of the French Army to stave off Wehrmacht Army Groups A, B, and C with their much revered Panzer divisions in the Low Countries. As the French 1st, 7th, 9th armies and the British Expeditionary Force moved in Belgium to meet Army Group B, the German Army Group A outflanked the Allies at the Battle of Sedan of 1940 by coming through the Ardennes, a broken and heavily forested terrain that had been believed to be impassable to armoured units. The Germans also rushed along the Somme valley toward the English Channel coast to catch the Allies in a large pocket that forced them into the disastrous Battle of Dunkirk. As a result of this brilliant German strategy, embodied in the Manstein Plan, the Allies were defeated in stunning fashion. France had to accept the terms imposed by Adolf Hitler at the Second Armistice at Compiègne, which was signed on 22 June 1940 in the same railway carriage in which the Germans had signed the armistice that ended the First World War on 11 November 1918.[97]

The Third Republic officially ended on 10 July 1940, when the French parliament gave full powers to Marshal Philippe Pétain, who proclaimed in the following days the État Français (the "French State"), commonly known as the "Vichy Regime" or "Vichy France" following its re-location to the town of Vichy in central France. Charles de Gaulle had made the Appeal of 18 June earlier, exhorting all French not to accept defeat and to rally to Free France and continue the fight with the Allies.

Throughout its seventy-year history, the Third Republic stumbled from crisis to crisis, from dissolved parliaments to the appointment of a mentally ill president (Paul Deschanel). It fought bitterly through the First World War against the German Empire, and the inter-war years saw much political strife with a growing rift between the right and the left. When France was liberated in 1944, few called for a restoration of the Third Republic, and a Constituent Assembly was established by the government of a provisional French Republic to draft a constitution for a successor, established as the Fourth Republic (1946 to 1958) that December, a parliamentary system not unlike the Third Republic.

Interpreting the Third Republic

Adolphe Thiers, first president of the Third Republic, called republicanism in the 1870s "the form of government that divides France least."[98] France might have agreed about being a republic, but it never fully accepted the Third Republic. France's longest-lasting governmental system since before the 1789 Revolution, the Third Republic was consigned to the history books as being unloved and unwanted in the end. Yet, its longevity showed that it was capable of weathering many storms.

One of the most surprising aspects of the Third Republic was that it constituted the first stable republican government in French history and the first to win the support of the majority of the population, but it was intended as an interim, temporary government. Following Thiers's example, most of the Orleanist monarchists progressively rallied themselves to the Republican institutions, thus giving support of a large part of the elites to the Republican form of government. On the other hand, the Legitimists remained harshly anti-Republicans, while Charles Maurras founded the Action française in 1898. This far-right monarchist movement became influential in the Quartier Latin in the 1930s. It also became a model for various far right leagues that participated to the 6 February 1934 riots that toppled the Second Cartel des gauches government.

Historiography of decadence

A major historiographical debate about the latter years of the Third Republic concerns the concept of La décadence (the decadence). Proponents of the concept have argued that the French defeat of 1940 was caused by what they regard as the innate decadence and moral rot of France.[99] The notion of la décadence as an explanation for the defeat began almost as soon as the armistice was signed in June 1940. Marshal Philippe Pétain stated in one radio broadcast, "The regime led the country to ruin." In another, he said "Our defeat is punishment for our moral failures" that France had "rotted" under the Third Republic.[100] In 1942 the Riom Trial was held bringing several leaders of the Third Republic to trial for declaring war on Germany in 1939 and accusing them of not doing enough to prepare France for war.

Marc Bloch in his book Strange Defeat (written in 1940, and published posthumously in 1946) argued that the French upper classes had ceased to believe in the greatness of France following the Popular Front victory of 1936, and so had allowed themselves to fall under the spell of fascism and defeatism. Bloch said that the Third Republic suffered from a deep internal "rot" that generated bitter social tensions, unstable governments, pessimism and defeatism, fearful and incoherent diplomacy, hesitant and shortsighted military strategy, and, finally, facilitated German victory in June 1940.[101] The French journalist André Géraud, who wrote under the pen name Pertinax in his 1943 book, The Gravediggers of France indicted the pre-war leadership for what he regarded as total incompetence.[101]

After 1945, the concept of la décadence was widely embraced by different French political fractions as a way of discrediting their rivals. The French Communist Party blamed the defeat on the "corrupt" and "decadent" capitalist Third Republic (conveniently hiding its own sabotaging of the French war effort during the Nazi-Soviet Pact and its opposition to the "imperialist war" against Germany in 1939–40).

From a different perspective, Gaullists called the Third Republic as a "weak" regime and argued that if France had a regime headed by a strong-man president like Charles de Gaulle before 1940, the defeat could have been avoided.[102] (In power, they did exactly that and started the Fifth Republic. Then was a group of French historians, centered around Pierre Renouvin and his protégés Jean-Baptiste Duroselle and Maurice Baumont, that started a new type of international history to take into what Renouvin called forces profondes (profound forces) such as the influence of domestic politics on foreign policy.[103] However, Renouvin and his followers still followed the concept of la décadence with Renouvin arguing that French society under the Third Republic was "sorely lacking in initiative and dynamism" and Baumont arguing that French politicians had allowed "personal interests" to override "...any sense of the general interest."[104]

In 1979, Duroselle published a well-known book entitled La Décadence that offered a total condemnation of the entire Third Republic as weak, cowardly and degenerate.[105] Even more so then in France, the concept of la décadence was accepted in the English-speaking world, where British historians such A. J. P. Taylor often described the Third Republic as a tottering regime on the verge of collapse.[106]

A notable example of the la décadence thesis was William L. Shirer's 1969 book The Collapse of the Third Republic, where the French defeat is explained as the result of the moral weakness and cowardice of the French leaders.[106] Shirer portrayed Édouard Daladier as a well-meaning, but weak willed; Georges Bonnet as a corrupt opportunist even willing to do a deal with the Nazis; Marshal Maxime Weygand as a reactionary soldier more interested in destroying the Third Republic than in defending it; General Maurice Gamelin as incompetent and defeatist, Pierre Laval as a crooked crypto-fascist; Charles Maurras (whom Shirer represented as France’s most influential intellectual) as the preacher of "drivel"; Marshal Philippe Pétain as the senile puppet of Laval and the French royalists, and Paul Reynaud as a petty politician controlled by his mistress, Countess Hélène de Portes. Modern historians who subscribe to la décadence argument or take a very critical view of France's pre-1940 leadership without necessarily subscribing to la décadence thesis include Talbot Imlay, Anthony Adamthwaite, Serge Berstein, Michael Carely, Nicole Jordan, Igor Lukes, and Richard Crane.[107]

The first historian to denounce la décadence concept explicitly was the Canadian historian Robert J. Young, who, in his 1978 book In Command of France argued that French society was not decadent, that the defeat of 1940 was due to only military factors, not moral failures, and that the Third Republic's leaders had done their best under the difficult conditions of the 1930s.[108] Young argued that the decadence, if it existed, did not impact French military planning and readiness to fight.[109][110] Young finds that American reporters in the late 1930s portrayed a calm, united, competent, and confident France. They praised French art, music, literature, theater, and fashion, and stressed French resilience and pluck in the face of growing Nazi aggression and brutality. Nothing in the tone or content of the articles foretold the crushing military defeat and collapse of June 1940.[111]

Young has been followed by other historians such as Robert Frankenstein, Jean-Pierre Azema, Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac, Martin Alexander, Eugenia Kiesling, and Martin Thomas, who argued that French weakness on the international stage was due to structural factors as the impact of the Great Depression had on French rearmament and had nothing to do with French leaders being too "decadent" and cowardly to stand up to Nazi Germany.[112]

Timeline to 1914

- September 1870: following the collapse of the Empire of Napoleon III in the Franco-Prussian War the Third Republic was created and the Government of National Defence ruled during the Siege of Paris (19 September 1870 – 28 January 1871).

- May 1871: The Treaty of Frankfurt (1871), the peace treaty ending the Franco-Prussian War. France lost Alsace and most of Lorraine, and had to pay a cash indemnity to the new nation of Germany.

- 1871: The Paris Commune. In a formal sense the Paris Commune of 1871 was simply the local authority that exercised power in Paris for two months in the spring of 1871. It was separate from that of the new government under Adolphe Thiers. The radical regime came to an end after a bloody suppression by Thiers's government in May 1871.

- 1872–73: After the nation faced the immediate political problems, it needed to establish a permanent form of government. Thiers wanted to base it on the constitutional monarchy of Britain, however he realised France would have to remain republican. In expressing this belief, he violated the Pact of Bordeaux, angering the Monarchists in the Assembly. As a result, he was forced to resign in 1873.

- 1873: Marshal MacMahon, a conservative Roman Catholic, was made President of the Republic. The Duc de Broglie, an Orleanist, as the prime minister. Unintentionally, the Monarchists had replaced an absolute monarchy by a parliamentary one.

- Feb 1875: Series of parliamentary Acts established the organic or constitutional laws of the new republic. At its apex was a President of the Republic. A two-chamber parliament was created, along with a ministry under the President of the Council, who was nominally answerable to both the President of the Republic and Parliament.

- May 1877: with public opinion swinging heavily in favour of a republic, the President of the Republic, Patrice MacMahon, himself a monarchist, made one last desperate attempt to salvage the monarchical cause by dismissing the republic-minded Prime Minister Jules Simon and reappointing the monarchist leader the Duc de Broglie to office. He then dissolved parliament and called a general election. If his hope had been to halt the move towards republicanism, it backfired spectacularly, with the President being accused of having staged a constitutional coup d'état, known as le seize Mai after the date when it happened.

- 1879: Republicans returned triumphant, finally killing off the prospect of a restored French monarchy by gaining control of the Senate on 5 January 1879. MacMahon himself resigned on 30 January 1879, leaving a seriously weakened presidency in the shape of Jules Grévy.

- 1880: The Jesuits and several other religious orders were dissolved, and their members were forbidden to teach in state schools.

- 1881: Following the 16 May crisis in 1877, Legitimists were pushed out of power, and the Republic was finally governed by republicans, called Opportunist Republicans as they were in favor of moderate changes to firmly establish the new regime. The Jules Ferry laws on free, mandatory and secular public education, voted in 1881 and 1882, were one of the first sign of this republican control of the Republic, as public education was not anymore in the exclusive control of the Catholic congregations.

- 1882: Religious instruction was removed from all state schools. The measures were accompanied by the abolition of chaplains in the armed forces and the removal of nuns from hospitals. Due to the fact that France was mainly Roman Catholic, this was greatly opposed.

- 1889: The Republic was rocked by the sudden but short-timed Boulanger crisis spawning the rise of the modern intellectual Émile Zola. Later, the Panama scandals also were quickly criticized by the press.

- 1893: Following anarchist Auguste Vaillant's bombing at the National Assembly, killing nobody but injuring one, deputies voted the lois scélérates which limited the 1881 freedom of the press laws. The following year, President Sadi Carnot was stabbed to death by Italian anarchist Caserio.

- 1894: The Dreyfus Affair: a Jewish artillery officer, Alfred Dreyfus, was arrested on charges relating to conspiracy and espionage. Allegedly, Dreyfus had handed over important military documents discussing the designs of a new French artillery piece to a German military attaché named Max von Schwartzkoppen.

- 1894: A strategic military alliance with the Russian Empire.

- 1898: Writer Émile Zola published an article entitled J'Accuse...! The article alleged an anti-Semitic conspiracy in the highest ranks of the military to scapegoat Dreyfus, tacitly supported by the government and the Catholic Church. The Fashoda Incident nearly causes an Anglo-French war.

- 1901: The Radical-Socialist Party is founded and remained the most important party of the Third Republic starting at the end of the 19th century. The same year, followers of Léon Gambetta, such as Raymond Poincaré, who became President of the Council in the 1920s, created the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD), which became the main center-right party after World War I and the parliamentary disappearance of monarchists and Bonapartists.

- 1904: French foreign minister Théophile Delcassé negotiated with Lord Lansdowne, the British Foreign Secretary, the Entente Cordiale in 1904.

- 1905: The government introduced the law on the separation of Church and State, heavily supported by Emile Combes, who had been strictly enforcing the 1901 voluntary association law and the 1904 law on religious congregations' freedom of teaching (more than 2,500 private teaching establishments were by then closed by the state, causing bitter opposition from the Catholic and conservative population).

- 1906: It became apparent that the documents handed over to Schwartzkoppen by Dreyfus in 1894 were a forgery and thus Dreyfus was pardoned after serving 12 years in prison.

- 1914: After SFIO (French Section of the Workers' International) leader Jean Jaurès's assassination a few days before the German invasion of Belgium, the French socialist movement, as the whole of the Second International, abandoned its antimilitarist positions and joined the national war effort. First World War begins.

See also

- French Fourth Republic

- French Fifth Republic

- French colonial empire

- French Presidential elections under the Third Republic

- 6 February 1934 crisis

- 16 May 1877 crisis

- Dreyfus Affair

- France in Modern Times I (1792-1920)

- France in Modern Times II (1920-today)

- List of French possessions and colonies

Notes

- ↑ Larkin, Maurice (2002). Religion, Politics and Preferment in France since 1890: La Belle Epoque and its Legacy. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-521-52270-6.

- ↑ D.W. Brogan, France Under the Republic: The Development of Modern France (1870-1939) (1940) pp 77-105.

- ↑ Steven D. Kale, "The Monarchy According to the King: The Ideological Content of the 'Drapeau Blanc,' 1871-1873." French History (1988) 2#4 pp 399-426.

- ↑ D.W. Brogan, France Under the Republic: The Development of Modern France (1870-1939) (1940) pp 106-13.

- ↑ Brogan, France Under the Republic: The Development of Modern France (1870-1939) (1940) pp 127-43.

- ↑ D.W. Brogan, France Under the Republic: The Development of Modern France (1870-1939) (1940) pp 144-79.

- ↑ Brogan, France Under the Republic: The Development of Modern France (1870-1939) (1940) pp 183-213.

- ↑ Mazgaj, Paul (1987). "The Origins of the French Radical Right: A Historiographical Essay". French Historical Studies. 15 (2): 287–315. JSTOR 286267.

- ↑ David McCullough, The path between the seas: the creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914 (2001) pp 45-242.

- ↑ Philip Nord, "The welfare state in France, 1870-1914." French Historical Studies 18.3 (1994): 821-838. in JSTOR

- ↑ Timothy B. Smith, "The ideology of charity, the image of the English poor law, and debates over the right to assistance in France, 1830–1905." Historical Journal 40.04 (1997): 997-1032.

- ↑ Allan Mitchell, The Divided Path: The German Influence on Social Reform in France After 1870 (1991) pp 252-75 excerpt

- ↑ Martha L. Hildreth, Doctors, Bureaucrats & Public Health in France, 1888-1902 (1987)

- ↑ Alisa Klaus, Every Child a Lion: The Origins of Maternal & Infant Health Policy in the United States & France, 1890-1920 (1993).

- ↑ Ann-Louise Shapiro, "Private Rights, Public Interest, and Professional Jurisdiction: The French Public Health Law of 1902." Bulletin of the History of Medicine 54.1 (1980): 4+

- ↑ Read, Piers Paul (2012). The Dreyfus Affair. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-60819-432-2.

- ↑ Wilson, Stephen (1976). "Antisemitism and Jewish Response in France during the Dreyfus Affair". European Studies Review. 6 (2): 225–248. doi:10.1177/026569147600600203.

- ↑ Hutton, Patrick H., ed. (1986). Historical Dictionary of the Third French Republic, 1870–1940. 2. London: Aldwych Press. pp. 690–694. ISBN 0-86172-046-6.

- 1 2 Collins, Ross F. (2001). "The Business of Journalism in Provincial France during World War I". Journalism History. 27 (3): 112–121. ISSN 0094-7679.

- ↑ Mather, Judson (1972). "The Assumptionist Response to Secularisation, 1870–1900". In Bezucha, Robert J. Modern European Social History. Lexington: D.C. Heath. pp. 59–89. ISBN 0-669-61143-3.

- ↑ See Zeldin, Theodore (1977). "Newspapers and corruption". France: 1848–1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 492–573. ISBN 0-19-822125-8. Also, pp 522–24 on foreign subsidies.

- ↑ Hutton, Patrick H., ed. (1986). Historical Dictionary of the Third French Republic, 1870–1940. 2. London: Aldwych Press. pp. 692–694. ISBN 0-86172-046-6.

- ↑ Amato, Joseph (1992). "Eugen Weber's France". Journal of Social History. 25 (4): 879–882. doi:10.1353/jsh/25.4.879. JSTOR 3788392.

- ↑ Margadant, Ted W. (1979). "French Rural Society in the Nineteenth Century: A Review Essay". Agricultural History. 53 (3): 644–651. JSTOR 3742761.

- ↑ Whitaker, Jan (2011). The World of Department Stores. New York: Vendome Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-86565-264-4.

- ↑ Miller, Michael B. (1981). Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store, 1869–1920. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05321-9.

- ↑ Homburg, Heidrun (1992). "Warenhausunternehmen und ihre Gründer in Frankreich und Deutschland oder: eine diskrete Elite und mancherlei Mythen" [Department store firms and their founders in France and Germany, or: a discreet elite and various myths] (PDF). Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte. 1992 (1): 183–219.

- ↑ Amelinckx, Frans C. (1995). "The Creation of Consumer Society in Zola's Ladies' Paradise". Proceedings of the Western Society for French History. 22: 17–21. ISSN 0099-0329.

- ↑ Wemp, Brian (2011). "Social Space, Technology, and Consumer Culture at the Grands Magasins Dufayel". Historical Reflections. 37 (1): 1–17. doi:10.3167/hrrh.2011.370101.

- ↑ McBride, Theresa M. (1978). "A Woman's World: Department Stores and the Evolution of Women's Employment, 1870–1920". French Historical Studies. 10 (4): 664–683. JSTOR 286519.

- ↑ Daughton, J. P. (2006). An Empire Divided: Religion, Republicanism, and the Making of French Colonialism, 1880–1914. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-537401-0.

- ↑ Evans, Martin (2000). "Projecting a Greater France". History Today. 50 (2): 18–25. ISSN 0018-2753.

- ↑ Aldrich, Robert (1996). Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-56739-0.

- ↑ Halpern, Avner (2002). "Freemasonry and party building in late 19th-Century France". Modern and Contemporary France. 10 (2): 197–210. doi:10.1080/09639480220126134.

- ↑ Stone, Judith F. (1988). "The Radicals and the Interventionist State: Attitudes, Ambiguities and Transformations, 1880–1910". French History. 2 (2): 173–186. doi:10.1093/fh/2.2.173.