Carbonic anhydrase

| Carbonate dehydratase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

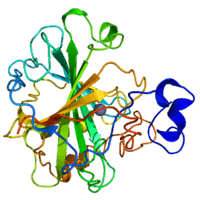

Ribbon diagram of human carbonic anhydrase II, with zinc ion visible in the center | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 4.2.1.1 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9001-03-0 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / EGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Eukaryotic-type carbonic anhydrase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Carb_anhydrase | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00194 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001148 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00146 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1can | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1can | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The carbonic anhydrases (or carbonate dehydratases) form a family of enzymes that catalyze the rapid interconversion of carbon dioxide and water to bicarbonate and protons (or vice versa), a reversible reaction that occurs relatively slowly in the absence of a catalyst.[1] The active site of most carbonic anhydrases contains a zinc ion; they are therefore classified as metalloenzymes.

One of the functions of the enzyme in animals is to interconvert carbon dioxide and bicarbonate to maintain acid-base balance in blood and other tissues, and to help transport carbon dioxide out of tissues.

Reaction

The reaction catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase is:

The reaction rate of carbonic anhydrase is one of the fastest of all enzymes, and its rate is typically limited by the diffusion rate of its substrates. Typical catalytic rates of the different forms of this enzyme ranging between 104 and 106 reactions per second.[3]

The reverse reaction is relatively slow (kinetics in the 15-second range) in the absence of a catalyst. This is why a carbonated drink does not instantly degas when opening the container; however it will rapidly degas in the mouth when it comes in contact with carbonic anhydrase that is contained in saliva.[4]

An anhydrase is defined as an enzyme that catalyzes the removal of a water molecule from a compound, and so it is this "reverse" reaction that gives carbonic anhydrase its name, because it removes a water molecule from carbonic acid.

Mechanism

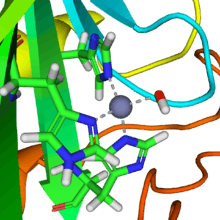

A zinc prosthetic group in the enzyme is coordinated in three positions by histidine side-chains. The fourth coordination position is occupied by water. This causes polarisation of the hydrogen-oxygen bond, making the oxygen slightly more positive, thereby weakening the bond.

A fourth histidine is placed close to the substrate of water and accepts a proton, in an example of general acid - general base catalysis (see the article "Acid catalysis"). This leaves a hydroxide attached to the zinc.

The active site also contains specificity pocket for carbon dioxide, bringing it close to the hydroxide group. This allows the electron-rich hydroxide to attack the carbon dioxide, forming bicarbonate.

Families

There are at least five distinct CA families (α, β, γ, δ and ε). These families have no significant amino acid sequence similarity and in most cases are thought to be an example of convergent evolution. The α-CAs are found in humans.

α-CA

The CA enzymes found in mammals are divided into four broad subgroups,[5] which, in turn consist of several isoforms:

- the cytosolic CAs (CA-I, CA-II, CA-III, CA-VII and CA XIII) (CA1, CA2, CA3, CA7, CA13)

- mitochondrial CAs (CA-VA and CA-VB) (CA5A, CA5B)

- secreted CAs (CA-VI) (CA6)

- membrane-associated CAs (CA-IV, CA-IX, CA-XII, CA-XIV and CA-XV) (CA4, CA9, CA12, CA14)

There are three additional "acatalytic" CA isoforms (CA-VIII, CA-X, and CA-XI) (CA8, CA10, CA11) whose functions remain unclear.[6]

| Isoform | Gene | Molecular mass[7] | Location (cell) | Location (tissue)[7] | Specific activity of human enzymes (except for mouse CA XV) (s−1)[8] | Sensitivity to sulfonamides (acetazolamide in this table) KI (nM)[8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA-I | CA1 | 29 kDa | cytosol | red blood cell and GI tract | 2.0 × 105 | 250 |

| CA-II | CA2 | 29 kDa | cytosol | almost ubiquitous | 1.4 × 106 | 12 |

| CA-III | CA3 | 29 kDa | cytosol | 8% of soluble protein in Type I muscle | 1.3 × 104 | 240000 |

| CA-IV | CA4 | 35 kDa | extracellular GPI-linked | GI tract, kidney, endothelium | 1.1 × 106 | 74 |

| CA-VA | CA5A | 34.7 kDa (predicted) | mitochondria | liver | 2.9 × 105 | 63 |

| CA-VB | CA5B | 36.4 kDa (predicted) | mitochondria | widely distributed | 9.5 × 105 | 54 |

| CA-VI | CA6 | 39-42 kDa | secretory | saliva and milk | 3.4 × 105 | 11 |

| CA-VII | CA7 | 29 kDa | cytosol | widely distributed | 9.5 × 105 | 2.5 |

| CA-IX | CA9 | 54, 58 kDa | cell membrane-associated | normal GI tract, several cancers | 1.1 × 106 | 16 |

| CA-XII | CA12 | 44 kDa | extracellularily located active site | kidney, certain cancers | 4.2 × 105 | 5.7 |

| CA-XIII[9] | CA13 | 29 kDa | cytosol | widely distributed | 1.5 × 105 | 16 |

| CA-XIV | CA14 | 54 kDa | extracellularily located active site | kidney, heart, skeletal muscle, brain | 3.1 × 105 | 41 |

| CA-XV[10] | CA15 | 34-36 kDa | extracellular GPI-linked | kidney, not expressed in human tissues | 4.7 × 105 | 72 |

β-CA

Most prokaryotic and plant chloroplast CAs belong to the beta family. Two signature patterns for this family have been identified:

- C-[SA]-D-S-R-[LIVM]-x-[AP]

- [EQ]-[YF]-A-[LIVM]-x(2)-[LIVM]-x(4)-[LIVMF](3)-x-G-H-x(2)-C-G

γ-CA

The gamma class of CAs come from methanogens, methane-producing bacteria that grow in hot springs.

δ-CA

The delta class of CAs has been described in diatoms. The distinction of this class of CA has recently[11] come into question, however.

ζ-CA

The zeta class of CAs occurs exclusively in bacteria in a few chemolithotrophs and marine cyanobacteria that contain cso-carboxysomes.[12] Recent 3-dimensional analyses[11] suggest that ζ-CA bears some structural resemblance to β-CA, particularly near the metal ion site. Thus, the two forms may be distantly related, even though the underlying amino acid sequence has since diverged considerably.

η-CA

The eta family of CAs was recently found in organisms of the genus Plasmodium. These are a group of enzymes previously thought to belong to the alpha family of CAs, however it has been demonstrated that η-CAs have unique features, such as their metal ion coordination pattern.[13]

Structure and function

Several forms of carbonic anhydrase occur in nature. In the best-studied α-carbonic anhydrase form present in animals, the zinc ion is coordinated by the imidazole rings of 3 histidine residues, His94, His96, and His119.

The primary function of the enzyme in animals is to interconvert carbon dioxide and bicarbonate to maintain acid-base balance in blood and other tissues, and to help transport carbon dioxide out of tissues.

There are at least 14 different isoforms in mammals. Plants contain a different form called β-carbonic anhydrase, which, from an evolutionary standpoint, is a distinct enzyme, but participates in the same reaction and also uses a zinc ion in its active site. In plants, carbonic anhydrase helps raise the concentration of CO2 within the chloroplast in order to increase the carboxylation rate of the enzyme RuBisCO. This is the reaction that integrates CO2 into organic carbon sugars during photosynthesis, and can use only the CO2 form of carbon, not carbonic acid or bicarbonate.

Cadmium-containing Carbonic Anhydrase

Marine diatoms have been found to express a new form of ζ carbonic anhydrase. T. weissflogii, a species of phytoplankton common to many marine ecosystems, was found to contain carbonic anhyrdase with a cadmium ion in place of zinc.[14] Previously, it had been believed that cadmium was a toxic metal with no biological function whatsoever. However, this species of phytoplankton appears to have adapted to the low levels of zinc in the ocean by using cadmium when there is not enough zinc.[15] Although the concentration of cadmium in sea water is also low (about 1x10−16 molar), there is an environmental advantage to being able to use either metal depending on which is more available at the time. This type of carbonic anhydrase is therefore cambialistic, meaning it can interchange the metal in its active site with other metals (namely, zinc and cadmium).[16]

Similarities To Other Carbonic Anhydrases

The mechanism of cadmium carbonic anhydrase (CDCA) is essentially the same as that of other carbonic anhydrases in its conversion of carbon dioxide and water into bicarbonate and a proton.[17] Additionally, like the other carbonic anhydrases, CDCA makes the reaction go almost as fast as the diffusion rate of its substrates, and it can be inhibited by sulfonamide and sulfamate derivatives.[17]

Differences From Other Carbonic Anhydrases

Unlike most other carbonic anhydrases, the active site metal ion is not bound by three histidine residues and a hydroxide ion. Instead, it is bound by two cysteine residues, one histidine residue, and a hydroxide ion, which is characteristic of β-CA.[17][18] Due to the fact that cadmium is a soft acid, it will be more tightly bound by soft base ligands.[16] The sulfur atoms on the cysteine residues are soft bases, thus binding the cadmium more tightly than the nitrogen on histidine residues would. CDCA also has a three-dimensional folding structure that is unlike any other carbonic anhydrase, and its amino acid sequence is dissimilar to the other carbonic anhydrases.[17] It is a monomer with three domains, each one identical in amino acid sequence and each one containing an active site with a metal ion.[18]

Another key difference between CDCA and the other carbonic anhydrases is that CDCA has a mechanism for switching out its cadmium ion for a zinc ion in the event that zinc becomes more available to the phytoplankton than cadmium. The active site of CDCA is essentially "gated" by a chain of nine amino acids with glycine residues at positions 1 and 9. Normally, this gate remains closed and the cadmium ion is trapped inside. However, due to the flexibility and position of the glycine residues, this gate can be opened in order to remove the cadmium ion. A zinc ion can then be put in its place and the gate will close behind it.[17] As a borderline acid, zinc will not bind as tightly to the cysteine ligands as cadmium would, but the enzyme will still be active and reasonably efficient. The metal in the active site can be switched between zinc and cadmium depending on which one is more abundant at the time. It is the ability of CDCA to utilize either cadmium or zinc that likely gives T. weissflogii a survival advantage.[15]

Transport of Cadmium

Cadmium is still considered lethal to phytoplankton in high amounts. Studies have shown that T. weissflogii has an initial toxic response to cadmium when exposed to it. The toxicity of the metal is reduced by the transcription and translation of phytochelatin, which are proteins that can bind and transport cadmium. Once bound by phytochelatin, cadmium is no longer toxic, and it can be safely transported to the CDCA enzyme.[14] It's also been shown that the uptake of cadmium via phytochelatin leads to a significant increase in CDCA expression.[14]

CDCA-like Proteins

Other phytoplankton from different water sources have been tested for the presence of CDCA. It was found that many of them contain proteins that are homologous to the CDCA found in T. weissflogii.[14] This includes species from Great Bay, New Jersey as well as in the Pacific Ocean near the equator. In all species tested, CDCA-like proteins showed high levels of expression even in high concentrations of zinc and in the absence of cadmium.[14] The similarity between these proteins and the CDCA expressed by T. weissflogii varied, but they were always at least 67% similar.[14]

Industrial applications

Modified carbonic anhydrase enzymes have been used to replace methyl diethanolamine ("MDEA") in carbon dioxide capture.

See also

References

- ↑ Badger MR, Price GD (1994). "The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis". Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Bio. 45: 369–392. doi:10.1146/annurev.pp.45.060194.002101.

- ↑ Carbonic acid has a pKa of around 6.36 (the exact value depends on the medium) so at pH 7 a small percentage of the bicarbonate is protonated. See carbonic acid for details concerning the equilibria HCO−

3 + H+ H2CO3 and H2CO3 CO2 + H2O - ↑ Lindskog S (1997). "Structure and mechanism of carbonic anhydrase". Pharmacol. Ther. 74 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(96)00198-2. PMID 9336012.

- ↑ Thatcher BJ, Doherty AE, Orvisky E, Martin BM, Henkin RI (September 1998). "Gustin from human parotid saliva is carbonic anhydrase VI". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 250 (3): 635–41. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.9356. PMID 9784398.

- ↑ Breton S (2001). "The cellular physiology of carbonic anhydrases". JOP. 2 (4 Suppl): 159–64. PMID 11875253.

- ↑ Lovejoy DA, Hewett-Emmett D, Porter CA, Cepoi D, Sheffield A, Vale WW, Tashian RE (1998). "Evolutionarily conserved, "acatalytic" carbonic anhydrase-related protein XI contains a sequence motif present in the neuropeptide sauvagine: the human CA-RP XI gene (CA11) is embedded between the secretor gene cluster and the DBP gene at 19q13.3". Genomics. 54 (3): 484–93. doi:10.1006/geno.1998.5585. PMID 9878252.

- 1 2 Unless else specified: Boron WF (2005). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approaoch. Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3. Page 638

- 1 2 Hilvo M, Baranauskiene L, Salzano AM, Scaloni A, Matulis D, Innocenti A, Scozzafava A, Monti SM, Di Fiore A, De Simone G, Lindfors M, Jänis J, Valjakka J, Pastoreková S, Pastorek J, Kulomaa MS, Nordlund HR, Supuran CT, Parkkila S (2008). "Biochemical characterization of CA IX, one of the most active carbonic anhydrase isozymes". J. Biol. Chem. 283 (41): 27799–809. doi:10.1074/jbc.M800938200. PMID 18703501.

- ↑ Lehtonen J, Shen B, Vihinen M, Casini A, Scozzafava A, Supuran CT, Parkkila AK, Saarnio J, Kivelä AJ, Waheed A, Sly WS, Parkkila S (2004). "Characterization of CA XIII, a novel member of the carbonic anhydrase isozyme family". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (4): 2719–27. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308984200. PMID 14600151.

- ↑ Hilvo M, Tolvanen M, Clark A, Shen B, Shah GN, Waheed A, Halmi P, Hänninen M, Hämäläinen JM, Vihinen M, Sly WS, Parkkila S (2005). "Characterization of CA XV, a new GPI-anchored form of carbonic anhydrase". Biochem. J. 392 (Pt 1): 83–92. doi:10.1042/BJ20051102. PMC 1317667

. PMID 16083424.

. PMID 16083424. - 1 2 Sawaya MR, Cannon GC, Heinhorst S, Tanaka S, Williams EB, Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA (2006). "The structure of beta-carbonic anhydrase from the carboxysomal shell reveals a distinct subclass with one active site for the price of two". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (11): 7546–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M510464200. PMID 16407248.

- ↑ So AK, Espie GS, Williams EB, Shively JM, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC (2004). "A novel evolutionary lineage of carbonic anhydrase (zeta class) is a component of the carboxysome shell". J. Bacteriol. 186 (3): 623–30. doi:10.1128/JB.186.3.623-630.2004. PMC 321498

. PMID 14729686.

. PMID 14729686. - ↑ Del Prete S, Vullo D, Fisher GM, Andrews KT, Poulsen SA, Capasso C, Supuran CT (Sep 2014). "Discovery of a new family of carbonic anhydrases in the malaria pathogen Plasmodium falciparum--the η-carbonic anhydrases". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 24 (18): 4389–96. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.08.015. PMID 25168745.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Park H, McGinn PJ, More l F (19 May 2008). "Expression of cadmium carbonic anhydrase of diatoms in seawater". Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 51: 183–193. doi:10.3354/ame01192.

- 1 2 Lane TW, Saito MA, George GN, Pickering IJ, Prince RC, Morel FM (May 2005). "Biochemistry: a cadmium enzyme from a marine diatom". Nature. 435 (7038): 42. doi:10.1038/435042a. PMID 15875011.

- 1 2 Bertini I, Gray H, Stiefel E, Valentine J (2007). Biological Inorganic Chemistry: Structure and Reactivity (First ed.). Sausalito, California: University Science Books. ISBN 978-1-891389-43-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (2013). Cadmium from toxicity to essentiality. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-5179-8.

- 1 2 Xu Y, Feng L, Jeffrey PD, Shi Y, Morel FM (Mar 2008). "Structure and metal exchange in the cadmium carbonic anhydrase of marine diatoms". Nature. 452 (7183): 56–61. doi:10.1038/nature06636. PMID 18322527.

Further reading

- Lyall V, Alam RI, Phan DQ, Ereso GL, Phan TH, Malik SA, Montrose MH, Chu S, Heck GL, Feldman GM, DeSimone JA (September 2001). "Decrease in rat taste receptor cell intracellular pH is the proximate stimulus in sour taste transduction". Am. J. Physiol., Cell Physiol. 281 (3): C1005–13. PMID 11502578.

- Goodsell D (2004-01-01). "Carbonic Anhydrase". PDB Molecule of the Month. Protein Data Bank. Retrieved 2011-05-28.