Book of Daniel

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Book of Daniel is a biblical apocalypse, combining a prophesy of history with an eschatology (the study of last things) which is both cosmic in scope and political in its focus.[1] In more mundane language, it is "an account of the activities and visions of Daniel, a noble Jew exiled at Babylon."[2] In the Hebrew Bible it is found in the Ketuvim (writings), while in Christian Bibles it is grouped with the Major Prophets.[3] Its message is that just as the God of Israel saved Daniel and his friends from their enemies, so he would save all of Israel in their present oppression.[4]

The book divides into two parts, a set of six court tales in chapters 1–6 followed by four apocalyptic visions in chapters 7–12.[5] The Apocrypha contains three additional stories, the Song of the Three Holy Children, Susanna, and Bel and the Dragon[6]

Traditionally ascribed to Daniel himself, modern scholarly consensus considers the book pseudonymous, the stories of the first half legendary in origin, and the visions of the second the product of anonymous authors in the Maccabean period (2nd century BC).[5] Its influence has resonated through later ages, from the Dead Sea Scrolls community and the authors of the gospels and Revelation, to various movements from the 2nd century to the Protestant Reformation and modern millennialist movements – on whom it continues to have a profound influence.[7]

Structure

Divisions

The literary structure of the book of Daniel is marked by three prominent features. The most fundamental is a genre division between the court tales of chapters 1–6 and the apocalyptic visions of 7–12. The second is a language division between the Hebrew of chapters 1 and 8–12, and the Aramaic of chapters 2–7.[8][9] This language division is reinforced by the chiastic arrangement of the Aramaic chapters (see below). Various suggestions have been made by scholars to explain the fact that the genre division does not coincide with the other two. However, the most reasonable proposal is that put forward by John J. Collins: the language division and concentric structure of chapters 2-6 are artificial literary devices designed to bind the two halves of the book together.[10] It should also be noted that the time settings of chapters 1–6 show a progression from Babylonian to Median times, which is repeated (Babylonian to Persian) in chapters 7–12. The following outline is provided by Collins in his commentary on Daniel:[11]

PART I: Tales (chapters 1:1–6:29)

- 1: Introduction (1:1–21 – set in the Babylonian era, written in Hebrew)

- 2: Nebuchadnezzar's dream of four kingdoms (2:1–49 – Babylonian era; Aramaic)

- 3: The fiery furnace (3:1–30 – Babylonian era; Aramaic)

- 4: Nebuchadnezzar's madness (3:31–4:34 – Babylonian era; Aramaic)

- 5: Belshazzar's feast (5:1–6:1 – Babylonian era; Aramaic)

- 6: Daniel in the lions' den (6:2–29 – Median era with mention of Persia; Aramaic)

PART II: Visions (chapters 7:1–12:13)

- 7: The beasts from the sea and the Son of Man (7:1–28 – Babylonian era: Aramaic)

- 8: The ram and the he-goat (8:1–27 – Babylonian era; Hebrew)

- 9: Interpretation of Jeremiah's prophecy of the seventy weeks (9:1–27 – Median era; Hebrew)

- 10: The angel's revelation: kings of the north and south (10:1–12:13 – Persian era, mention of Greek era; Hebrew)

Chiastic structure in the Aramaic section

There is a clear chiasm (a concentric literary structure in which the main point of a passage is often placed in the centre and framed by parallel elements on either side in "ABBA" fashion) in the chapter arrangement of the Aramaic section. The following is taken from Paul Redditt's "Introduction to the Prophets":[12]

- A1 (2:4b-49) – A dream of four kingdoms replaced by a fifth

- B1 (3:1–30) – Daniel's three friends in the fiery furnace

- C1 (4:1–37) – Daniel interprets a dream for Nebuchadnezzar

- C2 (5:1–31) – Daniel interprets the handwriting on the wall for Belshazzar

- B2 (6:1–28) – Daniel in the lions' den

- B1 (3:1–30) – Daniel's three friends in the fiery furnace

- A2 (7:1–28) – A vision of four world kingdoms replaced by a fifth

Content

Induction in Babylon (chapter 1)

In the third year of King Jehoiakim, God allows Jerusalem to fall into the power of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon.[Notes 1] Young Israelites of noble and royal family, "without physical defect, and handsome," versed in wisdom and competent to serve in the palace of the king, are taken to Babylon to be taught the literature and language of the Chaldeans. Among them are Daniel and his three companions, who refuse to touch the royal food and wine for fear of defilement. Their overseer fears for his life in case the health of his charges deteriorates, but Daniel suggests a trial and the four emerge healthier than their counterparts from ten days of nothing but vegetables and water. They are allowed to continue to refrain from eating the king's food, and to Daniel God gives insight into visions and dreams. When their training is done Nebuchadnezzar finds them 'ten times better' than all the wise men in his service and therefore keeps them at his court, where Daniel continues until the first year of King Cyrus.[13][Notes 2]

Nebuchadnezzar's dream of four kingdoms (chapter 2)

In the second year of his reign Nebuchadnezzar is troubled by a dream, and demands that his wise men tell him its content. When the wise men protest that this is beyond the power of any man he sentences all, including Daniel and his friends, to death. Daniel receives an explanatory vision from God: Nebuchadnezzar had seen an enormous statue with a head of gold, breast and arms of silver, belly and thighs of bronze, legs of iron, and feet of mixed iron and clay, then saw the statue destroyed by a rock that turned into a mountain filling the whole earth. Daniel explains the dream to the king: the statue symbolized four successive kingdoms, starting with Nebuchadnezzar, all of which would be crushed by God's kingdom, which would endure forever. Nebuchadnezzar acknowledges the supremacy of Daniel's god, raises him over all his wise men, and places him and his companions over the province of Babylon.[14]

The fiery furnace (chapter 3)

Daniel's companions Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego refuse to bow to King Nebuchadnezzar's golden statue and are thrown into a fiery furnace. Nebuchadnezzar is astonished to see a fourth figure in the furnace with the three, one "with the appearance like a son of the gods." So the king called the three to come out of the fire, and blessed the God of Israel, and decreed that any who blasphemed against him should be torn limb from limb.[15]

Nebuchadnezzar's madness (chapter 4)

.jpg)

Nebuchadnezzar recounts a dream of a huge tree that is suddenly cut down at the command of a heavenly messenger. Daniel is summoned and interprets the dream. The tree is Nebuchadnezzar himself, who for seven years will lose his mind and live like a wild beast. All of this comes to pass until, at the end of the specified time, Nebuchadnezzar acknowledges that "heaven rules" and his kingdom and sanity are restored.[16]

Belshazzar's feast (chapter 5)

Belshazzar and his nobles blasphemously drink from sacred Jewish temple vessels, offering praise to inanimate gods, until a hand mysteriously appears and writes upon the wall. The horrified king summons Daniel, who upbraids him for his lack of humility before God and interprets the message: Belshazzar's kingdom will be given to the Medes and Persians. Belshazzar rewards Daniel and raises him to be third in the kingdom, and that very night Belshazzar is slain and Darius the Mede takes the kingdom.[17][Notes 3]

Daniel in the lions' den (chapter 6)

Darius elevated Daniel to high office, exciting the jealousy of other officials. Knowing of Daniel's devotion to his God, his enemies trick the king into issuing an edict forbidding worship of any other god or man for a 30-day period. Daniel continues to pray three times a day to God towards Jerusalem; he is accused and King Darius, forced by his own decree, throws Daniel into the lions' den. But God shuts up the mouths of the lions and the next morning Darius rejoiced to find him unharmed. The king casts Daniel's accusers into the lions' pit together with their wives and children to be instantly devoured, while he himself acknowledges Daniel's God as he whose kingdom shall never be destroyed.[18]

Vision of the beasts from the sea (chapter 7)

In the first year of Belshazzar Daniel has a dream of four monstrous beasts arising from the sea.[Notes 4] The fourth, a beast with ten horns, devours the whole earth, treading it down and crushing it, and a further small horn appears and uproots three of the earlier horns. The Ancient of Days judges and destroys the beast, and "one like a son of man" is given everlasting kingship over the entire world. A divine being explains that the four beasts represent four kings, but that "the holy ones of the Most High" would receive the everlasting kingdom. The fourth beast would be a fourth kingdom with ten kings, and another king who would pull down three kings and make war on the "holy ones" for "a time, two times and a half," after which the heavenly judgement will be made against him and the "holy ones" will receive the everlasting kingdom.[19]

Vision of the ram and goat (chapter 8)

In the third year of Belshazzar Daniel has vision of a ram and goat. The ram has two mighty horns, one longer than the other, and it charges west, north and south, overpowering all other beasts. A goat with a single horn appears from the west and destroys the ram. The goat becomes very powerful until the horn breaks off and is replaced by four lesser horns. A small horn that grows very large, it stops the daily temple sacrifices and desecrates the sanctuary for two thousand three hundred "evening and mornings" (which could be either 1150 or 2300 days) until the temple is cleansed. The angel Gabriel informs him that the ram represents the Medes and Persians, the goat is Greece, and the "little horn" is a wicked king.[20]

Vision of the Seventy Weeks (chapter 9)

In the first year of Darius the Mede, Daniel meditates on the word of Jeremiah that the desolation of Jerusalem would last seventy years; he confesses the sin of Israel and pleads for God to restore Israel and the "desolated sanctuary" of the Temple. The angel Gabriel explains that the seventy years stand for seventy "weeks" of years (490 years), during which the Temple will first be restored, then later defiled by a "prince who is to come," "until the decreed end is poured out."[21]

Vision of the kings of north and south (chapters 10–12)

Daniel 10: In the third year of Cyrus[Notes 5] Daniel sees in his vision an angel (called "a man", but clearly a supernatural being) who explains that he is in the midst of a war with the "prince of Persia", assisted only by Michael, "your prince." The "prince of Greece" will shortly come, but first he will reveal what will happen to Daniel's people.

Daniel 11: A future king of Persia will make war on the king of Greece, a "mighty king" will arise and wield power until his empire is broken up and given to others, and finally the king of the south (identified in verse 8 as Egypt) will go to war with the "king of the north." After many battles (described in great detail) a "contemptible person" will become king of the north; this king will invade the south two times, the first time with success, but on his second he will be stopped by "ships of Kittim." He will turn back to his own country, and on the way his soldiers will desecrate the Temple, abolish the daily sacrifice, and set up the abomination of desolation. He will defeat and subjugate Libya and Egypt, but "reports from the east and north will alarm him," and he will meet his end "between the sea and the holy mountain."

Daniel 12: At this time Michael will come. It will be a time of great distress, but all those whose names are written will be delivered. "Multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake, some to everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt; those who are wise will shine like the brightness of the heavens, and those who lead many to righteousness, like the stars for ever and ever." In the final verses the remaining time to the end is revealed: "a time, times and half a time" (three years and a half). Daniel fails to understand and asks again what will happen, and is told: "From the time that the daily sacrifice is abolished and the abomination that causes desolation is set up, there will be 1,290 days. Blessed is the one who waits for and reaches the end of the 1,335 days."

Additions to Daniel (Greek text tradition)

The Greek text of Daniel is considerably longer than the Hebrew, due to three additional stories: they were accepted by all branches of Christianity until the Protestant movement rejected them in the 16th century on the basis that they were absent from Hebrew Bibles, but remain in Catholic and Orthodox Bibles.[22]

- The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children, placed after Daniel 3:23;

- The story of Susanna and the Elders, placed before chapter 1 in some Greek versions and after chapter 12 in others;

- The story of Bel and the Dragon, placed at the end of the book.

Historical background

The visions of chapters 7–12 reflect the crisis which took place in Judea in 167–164 BC when Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Greek king of the Seleucid Empire, threatened to destroy traditional Jewish worship in Jerusalem.[23] When Antiochus came to the throne the Jews were largely pro-Seleucid. The High Priestly family was split by rivalry, and one member, Jason, offered the king a large sum to be made High Priest. Jason also asked – or more accurately, paid – to be allowed to make Jerusalem a polis, or Greek city. This meant, among other things, that city government would be in the hands of the citizens, which meant in turn that citizenship would be a valuable commodity, to be purchased from Jason. None of this threatened the Jewish religion, and the reforms were widely welcomed, especially among the Jerusalem aristocracy and the leading priests. Three years later Jason was deposed when another priest, Menelaus, offered Antiochus an even larger sum for the post of High Priest.[24]

Antiochus invaded Egypt twice, in 169 BC with success, but on the second incursion, in late 168, he was forced to withdraw by the Romans.[25] Jason, hearing a rumour that Antiochus was dead, attacked Menelaus to take back the High Priesthood.[25] Antiochus drove Jason out of Jerusalem, plundered the Temple, and introduced measures to pacify his Egyptian border by imposing complete Hellenisation: the Jewish Book of the Law was prohibited and on 15 December 167 an "abomination of desolation", probably a Greek altar, was introduced into the Temple.[26] With the Jewish religion now clearly under threat a resistance movement sprang up, led by the Maccabee brothers, and over the next three years it won sufficient victories over Antiochus to take back and purify the Temple.[25]

The crisis which the author of Daniel addresses is the destruction of the altar in Jerusalem in 167 BC (first introduced in chapter 8:11): the daily offering which used to take place twice a day, at morning and evening, stopped, and the phrase "evenings and mornings" recurs through the following chapters as a reminder of the missed sacrifices.[27] But whereas the events leading up to the sacking of the Temple in 167 and the immediate aftermath are remarkably accurate (chapter 11:21–29), the predicted war between the Syrians and the Egyptians (11:40–43) never took place, and the prophecy that Antiochus would die in Palestine (11:44–45) was inaccurate (he died in Persia).[28] The conclusion is that the account must have been completed near the end of the reign of Antiochus but before his death in December 164, or at least before news of it reached Jerusalem.[29]

Composition

Development

It is generally accepted that Daniel originated as a collection of Aramaic court tales later expanded by the Hebrew revelations.[30] The court tales may have originally circulated independently, but the edited collection was probably composed in the third or early second century BC.[31] The first stage may have consisted of the stories in chapters 4–6, as these differ quite markedly in the Septuagint.[32] When the full collection was assembled, it is likely that the brief Aramaic introduction of chapter 1 was composed to provide historical context, introduce the characters of the tales, and explain how Daniel and his friends came to Babylon.[32] In the third stage, the visions of chapters 7–12 were added and chapter one was translated into Hebrew.[32] It should be noted that some commentators view the addition of chapter 7 as an intermediary step between the second and third stages of this process. [33]

Authorship

Daniel is one of a large number of Jewish apocalypses, all of them pseudonymous.[34] Although the entire book is traditionally ascribed to Daniel the seer, chapters 1–6 are in the voice of an anonymous narrator, except for chapter 4 which is in the form of a letter from king Nebuchadnezzar; only the second half (chapters 7–12) is presented by Daniel himself, introduced by the anonymous narrator in chapters 7 and 10.[35] The real author/editor of Daniel was probably an educated Jew, knowledgeable in Greek learning, and of high standing in his own community. The book is a product of "Wisdom" circles, but the type of wisdom is mantic (the discovery of heavenly secrets from earthly signs) rather than the wisdom of learning – the main source of wisdom in Daniel is God's revelation.[36][37]

It is possible that the name of Daniel was chosen for the hero of the book because of his reputation as a wise seer in Hebrew tradition.[38] Ezekiel, who lived during the Babylonian exile, mentioned him in association with Noah and Job (Ezekiel 14:14) as a figure of legendary wisdom (28:3), and a hero named Daniel (more accurately Dan'el, but the spelling is close enough for the two to be regarded as identical) features in a late 2nd millennium myth from Ugarit.[39] "The legendary Daniel, known from long ago but still remembered as an exemplary character ... serves as the principal human "hero" in the biblical book that now bears his name"; Daniel is the wise and righteous intermediary who is able to interpret dreams and thus convey the will of God to humans, the recipient of visions from on high that are interpreted to him by heavenly intermediaries.[40]

Dating

The prophecies of Daniel are accurate down to the career of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, king of Syria and oppressor of the Jews, but not in its prediction of his death: the author seems to know about Antiochus' two campaigns in Egypt (169 and 167 BC), the desecration of the Temple (the "abomination of desolation"), and the fortification of the Akra (a fortress built inside Jerusalem), but he seems to know nothing about the reconstruction of the Temple or about the actual circumstances of Antiochus' death in late 164. Chapters 10–12 must therefore have been written between 167 and 164 BC. There is no evidence of a significant time lapse between those chapters and chapters 8 and 9, and chapter 7 may have been written just a few months earlier again.[41]

Further evidence of the book's date is in the fact that Daniel is excluded from the Hebrew Bible's canon of the prophets, which was closed around 200 BC, and the Wisdom of Sirach, a work dating from around 180 BC, draws on almost every book of the Old Testament except Daniel, leading scholars to suppose that its author was unaware of it. Daniel is, however, quoted in a section of the Sibylline Oracles commonly dated to the middle of the 2nd century BC, and was popular at Qumran at much the same time, suggesting that it was known and revered from the middle of that century.[42]

Manuscripts

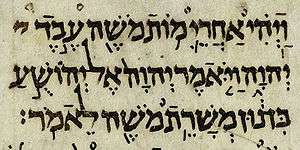

The Book of Daniel is preserved in the twelve-chapter Masoretic Text and in two longer Greek versions, the original Septuagint version, c. 100 BC, and the later Theodotion version from c. 2nd century AD. Both Greek texts contain three additions to Daniel: The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children; the story of Susannah and the Elders; and the story of Bel and the Dragon. Theodotion is much closer to the Masoretic Text and became so popular that it replaced the original Septuagint version in all but two manuscripts of the Septuagint itself.[43][44][8] The Greek additions were apparently never part of the Hebrew text.[45]

A total of eight incomplete copies of the Book of Daniel have been found at Qumran, two in Cave 1, five in Cave 4, and one in Cave 6. None is complete, but between them they preserve text from eleven of Daniel's twelve chapters, and the twelfth is quoted in the Florilegium (a compilation scroll) 4Q174, showing that the book at Qumran did not lack this conclusion. All eight manuscripts were copied between 125 BC (4QDanc) and about 50 AD (4QDanb), showing that Daniel was being read at Qumran only forty years after its composition. All appear to preserve the 12-chapter Masoretic version rather than the longer Greek text. None reveal any major disagreements against the Masoretic, and the four scrolls that preserve the relevant sections (1QDana, 4QDana, 4QDanb, and 4QDand) all follow the bilingual nature of Daniel where the book opens in Hebrew, switches to Aramaic at 2:4b, then reverts to Hebrew at 8:1.[46]

Genre, meaning, symbolism and chronology

(This section deals with modern scholarly reconstructions of the meaning of Daniel to its original authors and audience)

Genre

Daniel is an apocalypse, a literary genre in which a heavenly reality is revealed to a human recipient; such works are characterized by visions, symbolism, an other-worldly mediator, an emphasis on cosmic events, angels and demons, and pseudonymity (false authorship).[47] Apocalypses were common from 300 BC to 100 AD, not only among Jews and Christians, but Greeks, Romans, Persians and Egyptians.[48] Daniel, the book's hero, is a representative apocalyptic seer, the recipient of the divine revelation: has learned the wisdom of the Babylonian magicians and surpassed them, because his God is the true source of knowledge; he is one of the maskil, the wise, whose task is to teach righteousness.[48]

The book is also an eschatology: the divine revelation concerns the end of the present age, a moment in which God will intervene in history to usher in the final kingdom.[49] No real details of the end-time are given in Daniel, but it seems that God's kingdom will be on this earth, that it will be governed by justice and righteousness, and that the tables will be turned on the Seleucids and those Jews who cooperated with them.[50]

Meaning, symbolism and chronology

The message of the Book of Daniel is that, just as the God of Israel saved Daniel and his friends from their enemies, so he would save all Israel in their present oppression.[4] The book is filled with monsters, angels, and numerology, drawn from a wide range of sources, both biblical and non-biblical, that would have had meaning in the context of 2nd century Jewish culture, and while Christian interpreters have always viewed these as predicting events in the New Testament – "the Son of God", "the Son of Man", Christ and the Antichrist - the book's intended audience is the Jews of the 2nd century BCE.[51] The following explains a few of these predictions, as understood by modern biblical scholars.

- The four kingdoms and the little horn (Daniel 2 and 7): The concept of four successive world empires stems from Greek theories of mythological history;[52] most modern interpreters agree that the four represent Babylon, the Medes, Persia and the Greeks, ending with Hellenistic Seleucid Syria and with Hellenistic Ptolemaic Egypt.[53] The symbolism of four metals in the statue in chapter 2 comes from Persian writings,[52] while the four "beasts from the sea" in chapter 7 reflect Hosea 13:7–8, in which God threatens that he will be to Israel like a lion, a leopard, a bear or a wild beast.[54] The consensus among scholars is that the four beasts of chapter 7, like the metals of chapter 2, symbolise Babylon, Media, Persia and the Seleucids, with Antiochus IV (reigned 175-164 BC) as the "small horn" that uproots three others (Antiochus usurped the rights of several other claimants to become king of the Seleucid Empire).[55]

- The Ancient of Days and the one like a son of man (Daniel 7): The portrayal of God in Daniel 7:13 resembles the portrayal of the Canaanite god El as an ancient divine king presiding over the divine court.[56] The "Ancient of Days" gives dominion over the earth to "one like a son of man": scholars are almost universally agreed that this represents "the people of the holy ones of the Most High" (Daniel 7:27), meaning the "maskilim", the community responsible for Daniel,[57]

- The ram and he-goat (Daniel 8) as conventional astrological symbols represent Persia and Syria, as the text explains. The "mighty horn" stands for Alexander the Great (reigned 336-323 BC) and the "four lesser horns" represent the four principal generals (Diadochi) who fought over the Macedonian empire following Alexander's death. The "little horn" again represents Antiochus IV. The key to the symbols lies in the description of the little horn's actions: he ends the continual burnt offering and overthrows the Sanctuary, a clear reference to Antiochus' desecration of the Temple.[58]

- The anointed ones and the seventy years (Chapter 9): Daniel reinterprets Jeremiah's "seventy years" prophecy regarding the period Israel would spend in bondage to Babylon. From the point of view of the Maccabean era, Jeremiah's promise was obviously not true – the gentiles still oppressed the Jews, and the "desolation of Jerusalem" had not ended. Daniel therefore reinterprets the seventy years as seventy "weeks" of years, making up 490 years. The 70 weeks/490 years are subdivided, with seven "weeks" from the "going forth of the word to rebuild and restore Jerusalem" to the coming of an "anointed one", while the final "week" is marked by the violent death of another "anointed one", probably the High Priest Onias III (ousted to make way for Jason and murdered in 171 BC), and the profanation of the Temple. The point of this for Daniel is that the period of gentile power is predetermined, and is coming to an end.[59][60]

- Kings of north and south: Chapters 10 to 12 concern the war between these kings, the events leading up to it, and its heavenly meaning. In chapter 10 the angel (Gabriel?) explains that there is currently a war in heaven between Michael, the angelic protector of Israel, and the "princes" (angels) of Persia and Greece; then, in chapter 11, he outlines the human wars which accompany this – the mythological concept sees standing behind every nation a god/angel who does battle on behalf of his people, so that earthly events reflect what happens in heaven. The wars of the Ptolemies ("kings of the south") against the Seleucids ("kings of the north") are reviewed down to the career of Antiochus the Great (Antiochus III (reigned 222-187 BC), father of Antiochus IV), but the main focus is Antiochus IV, to whom more than half the chapter is devoted. The accuracy of these predictions lends credibility to the real prophecy with which the passage ends, the death of Antiochus – which, in the event, was not accurate.[61]

- Predicting the end-time (Daniel 8:14 and 12:7–12): Biblical eschatology does not generally give precise information as to when the end will come,[62] and Daniel's attempts to specify the number of days remaining is a rare exception.[63] Daniel asks the angel how long the "little horn" will be triumphant, and the angel replies that the Temple will be reconsecrated after 2,300 "evenings and mornings" have passed (Daniel 8:14). The angel is counting the two daily sacrifices, so the period is 1,150 days from the desecration in December 167. In chapter 12 the angel gives three more dates: the desolation will last "for a time, times and half a time", or a year, two years, and a half a year (Daniel 12:8); then that the "desolation" will last for 1,290 days (12:11); and finally, 1,335 days (12:12). Verse 12:11 was presumably added after the lapse of the 1,150 days of chapter 8, and 12:12 after the lapse of the number in 12:11.[64]

Influence

Religion

The concepts of immortality and resurrection, with rewards for the righteous and punishment for the wicked, have roots much deeper than Daniel, but the first clear statement is found in the final chapter of that book: "Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to everlasting shame and contempt."[65] Without this belief, Christianity, in which the resurrection of Jesus plays a central role, would have disappeared, like the movements following other charismatic Jewish figures of the 1st century.[66]

Daniel was quoted and referenced by both Jews and Christians the 1st century AD as predicting the imminent end-time.[67] Moments of national and cultural crisis continually reawakened the apocalyptic spirit, through the Montanists of the 2nd/3rd centuries, persecuted for their millennialism, to the more extreme elements of the 16th century Reformation such as the Zwickau prophets and the Münster Rebellion.[7] During the English Civil War, the Fifth Monarchy Men took their name and political program from Daniel 7, demanding that Oliver Cromwell allow them to form a "government of saints" in preparation for the coming of the Messiah; when Cromwell refused, they identified him instead as the Beast usurping the rightful place of King Jesus.[68] Daniel remains one of the most influential apocalypses in modern America, foretelling the history of Jesus and the Second Coming.[69]

The influence of Daniel has not been confined to Judaism and Christianity: In the Middle Ages Muslims created horoscopes whose authority was attributed to Daniel. More recently the Bahá'í movement, which originated in Persian Shi'ite Islam, justified its existence on the 1,260-day prophecy of Daniel, holding that it foretold the coming of the Twelfth Imam and an age of peace and justice in the year 1844, which is the year 1260 of the Muslim era.[70]

Western culture

Daniel belongs not only to the religious tradition but also to the wider Western intellectual and artistic heritage. The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature states that the Anglo-Saxons in Britain bypassed the Christian messages in Daniel 1-6, and instead used it "as a historical book, a repository of dramatic stories about confrontations between God and a series of emperor-figures who represent the highest reach of man"[71] In the early modern period the physicist Isaac Newton paid special attention to it, and Francis Bacon borrowed a motto from it for his work Novum Organum. Philosophers such as (Spinoza) drew on it. In the 20th century its apocalyptic second half of the book attracted the attention of Carl Jung. The book has also inspired musicians, from medieval liturgical drama to the 20th century compositions of Darius Milhaud. Artists including Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Delacroix have all drawn on its imagery.[70]

Notes

- ↑ Jehoiakim: King of Judah 608-598 BC; his third year would be either 606 or 605, depending how years are counted.

- ↑ Cyrus: Persian conqueror of Babylon, 539 BC.

- ↑ Darius the Mede: No such person is known to history (see Levine, 2010, page 1245, footnote 31). "Darius" is in any case a Persian, not a Median, name. The Persian army which captured Babylon was under the command of a certain Gobryas (or Gubaru), on behalf of Cyrus, the Persian king. The author of Daniel may have introduced the reference to a Mede in order to fulfill Isaiah and Jeremiah, who prophesied that the Medes would overthrow Babylon, confusing the events of 539 with those of 520 BC, when Darius I captured Babylon after an uprising. See Hammer, 1976, pp.65-66.

- ↑ First year of Belshazzar: Probably 553 BC, when Belshazzar was given royal power by his father, Nabonidus. See Levine, 2010, p.1248, footnote 7.1-8.

- ↑ "Third year of Cyrus": 536 BC. The author has apparently counted back seventy years to the "third year of Jehoiakim," 606 BC, to round out Daniel's prophetic ministry. See Towner, page 149.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Collins1984, p. 33.

- ↑ Reid 2000, p. 315.

- ↑ Bandstra 2008, p. 445.

- 1 2 Brettler 2005, p. 218.

- 1 2 Collins 2002, p. 2.

- ↑ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 452.

- 1 2 Towner 1984, p. 2-3.

- 1 2 Collins 1984, p. 28.

- ↑ Provan 2003, p. 665.

- ↑ Collins 1984, p. 30-31.

- ↑ Collins 1984, p. 31.

- ↑ Redditt 2009, p. 177.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 19-20.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 31-33.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 50-51.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. 1241.

- ↑ Hammer 1976, p. 57-60.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. 1245-1247.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. 1248-1249.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. 1249-1251.

- ↑ Levine 2010, p. 1251-1252.

- ↑ McDonald 2012, p. 57.

- ↑ Harrington 1999, p. 109-110.

- ↑ Grabbe 2010, p. 6-13.

- 1 2 3 Grabbe 2010, p. 13-16.

- ↑ Sacchi 2010, p. 225-226.

- ↑ Davies 2006, p. 407.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 6-7.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 7.

- ↑ Collins 1993, p. 42.

- ↑ Collins 1984, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 Redditt 2008, p. 176-177.

- ↑ Collins 1998, p. 30.

- ↑ Hammer 1976, p. 2.

- ↑ Wesselius 2002, p. 295.

- ↑ Grabbe 2002b, p. 229-230,243.

- ↑ Davies 2006, p. 340.

- ↑ Redditt 2008, p. 180.

- ↑ Collins 2003, p. 69.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 4.

- ↑ Collins 1984, p. 101.

- ↑ Hammer 1976, p. 1-2.

- ↑ Harrington 1999, p. 119-120.

- ↑ Spencer 2002, p. 89.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ VanderKam & Flint 2013, p. 137-138.

- ↑ Crawford 2000, p. 73.

- 1 2 Davies 2006, p. 397-406.

- ↑ Carroll 2000, p. 420-421.

- ↑ Redditt 2009, p. 187.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 1-2.

- 1 2 Niskanen 2004, p. 27,31.

- ↑ Towner 1984, p. 34-36.

- ↑ Collins 1984, p. 80.

- ↑ Matthews & Moyes 2012, p. 260,269.

- ↑ Seow 2003, p. 3-4.

- ↑ Gabbe 2002a, p. 282.

- ↑ Collins 1984, p. 87.

- ↑ Collins 1998, p. 108-109.

- ↑ Matthews & Moyer 2012, p. 260.

- ↑ Collins 1998, p. 110-111.

- ↑ Carroll 2000, p. 420.

- ↑ Collins 1998, p. 114.

- ↑ Collins 1998, p. 99.

- ↑ Cohn 2002, p. 86-87.

- ↑ Schwartz 1992, p. 2.

- ↑ Grabbe 2002, p. 244.

- ↑ Weber 2007, p. 374.

- ↑ Boyer 1992, p. 24,30–31.

- 1 2 Doukhan 2000, p. 9.

- ↑ Malcolm Godden and Michael Lapidge, The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature, Cambridge University Press 2013, p. 231.

Bibliography

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2008). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth Publishing Company. ISBN 0495391050.

- Bar, Shaul (2001). A letter that has not been read: dreams in the Hebrew Bible. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press. ISBN 978-0-87820-424-3.

- Boyer, Paul S. (1992). When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern American Culture. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-95129-8.

- Brettler, Mark Zvi (2005). How To Read the Bible. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 9780827610019.

- Carroll, John T. (2000). "Eschatology". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Cohn, Shaye J.D. (2006). From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227432.

- Collins, John J. (1984). Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802800206.

- Collins, John J. (1998). The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to Jewish Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802843715.

- Collins, John J. (1993). Daniel. Fortress. ISBN 9780800660406.

- Collins, John J. (2001). Seers, Sibyls, and Sages in Hellenistic-Roman Judaism. BRILL. ISBN 9780391041103.

- Collins, John J. (2002). "Current Issues in the Study of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL. ISBN 9004116753.

- Collins, John J. (2003). "From Prophecy to Apocalypticism: The Expectation of the End". In McGinn, Bernard; Collins, John J.; Stein, Stephen J. The Continuum History of Apocalypticism. Continuum. ISBN 9780826415202.

- Collins, John J. (2013). "Daniel". In Lieb, Michael; Mason, Emma; Roberts, Jonathan. The Oxford Handbook of the Reception History of the Bible. Oxford UNiversity Press. ISBN 9780191649189.

- Crawford, Sidnie White (2000). "Apocalyptic". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press.

- Davies, Philip (2006). "Apocalyptic". In Rogerson, J. W.; Lieu, Judith M. The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford Handbooks Online.

- DeChant, Dell (2009). "Apocalyptic Communities". In Neusner, Jacob. World Religions in America: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Doukhan, Jacques (2000). Secrets of Daniel: wisdom and dreams of a Jewish prince in exile. Review and Herald Pub Assoc.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2002). "The Danilic Son of Man in the New Testament". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus. Continuum.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2002a). Judaic Religion in the Second Temple Period: Belief and Practice from the Exile to Yavneh. Routledge.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2002b). "A Dan(iel) For All Seasons". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- Hammer, Raymond (1976). The Book of Daniel. Cambridge University Press.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1999). Invitation to the Apocrypha. Eerdmans.

- Hill, Andrew E. (2009). "Daniel". In Garland, David E.; Longman, Tremper. Daniel—Malachi. Zondervan.

- Hill, Charles E. (2000). "Antichrist". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Horsley, Richard A. (2007). Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea. Presbyterian Publishing Corp.

- Knibb, Michael (2002). "The Book of Daniel in its Context". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2010). "Daniel". In Coogan, Michael D.; Brettler, Marc Z.; Newsom, Carol A. The new Oxford annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical books : New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press.

- Lucas, Ernest C. (2005). "Daniel, Book of". In Vanhoozer, Kevin J.; Bartholomew, Craig G.; Treier, Daniel J. Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible. Baker Academic.

- Matthews, Victor H.; Moyer, James C. (2012). The Old Testament: Text and Context. Baker Books.

- McDonald, Lee Martin (2012). Formation of the Bible: the Story of the Church's Canon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-59856-838-7. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- Miller, Steven R. (1994). Daniel. B&H Publishing Group.

- Niskanen, Paul (2004). The Human and the Divine in History: Herodotus and the Book of Daniel. Continuum.

- Provan, Iain (2003). "Daniel". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

- Redditt, Paul L. (2009). Introduction to the Prophets. Eerdmans.

- Reid, Stephen Breck (2000). "Daniel, Book of". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Rowland, Christopher (2007). "Apocalyptic Literature". In Hass, Andrew; Jasper, David; Jay, Elisabeth. The Oxford Handbook of English Literature and Theology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199271979.

- Ryken,, Leland; Wilhoit, Jim; Longman, Tremper (1998). Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830867332.

- Sacchi, Paolo (2004). The History of the Second Temple Period. Continuum. ISBN 9780567044501.

- Schwartz, Daniel R. (1992). Studies in the Jewish Background of Christianity. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161457982.

- Seow, C.L. (2003). Daniel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256753.

- Schiffman, Lawrence H. (1991). From Text to Tradition: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 9780881253726.

- Spencer, Richard A. (2002). "Additions to Daniel". In Mills, Watson E.; Wilson, Richard F. The Deuterocanonicals/Apocrypha. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865545106.

- Towner, W. Sibley (1984). Daniel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664237561.

- VanderKam, James C. (2010). The Dead Sea Scrolls Today. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802864352.

- VanderKam, James C.; Flint, Peter (2013). The meaning of the Dead Sea scrolls: their significance for understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity. HarperCollins.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BC. Cambridge University Press.

- Weber, Timothy P. (2007). "Millennialism". In Walls, Jerry L. The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology. Oxford University Press.

- Wesselius, Jan-Wim (2002). "The Writing of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL.

Further reading

- Baldwin, Joyce G. (1981). Donald J. Wiseman, ed. Daniel: an introduction and commentary. Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press. ISBN 978-0-87784-273-6.

- Briant, Pierre (1996). From Cyrus to Alexander. Librairie Artheme Fayard. Translation by Peter Daniels, 2002. Paris. p. 42. ISBN 1-57506-031-0.

- Brown, Raymond E.; Fitzmyer, Joseph A.; Murphy, Roland E., eds. (1999). The New Jerome Biblical Commentary. Prentice Hall. p. 1475. ISBN 0-13-859836-3.

- Carey, Greg (1999). Bloomquist, L. Gregory, ed. Vision and Persuasion: Rhetorical Dimensions of Apocalyptic Discourse (Google On-line Books). Chalice Press. p. 224. ISBN 0-8272-4005-8. Retrieved 2010-06-25.

- Casey, Maurice (1980). Son of Man: The interpretation and influence of Daniel 7. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 272. ISBN 0-281-03697-7.

lists ten commentators of the 'Syrian Tradition' who identify the fourth beast of chapter 7 as Greece, the little horn as Antiochus, and – in the majority of instances – the "saints of the Most High" as Maccabean Jews.

- Cohn-Sherbok, Dan (1996). The Hebrew Bible (Google on-line books). Cassell. p. 257. ISBN 0-304-33703-X. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- Colless, Brian (1992). "Cyrus the Persian as Darius the Mede in the Book of Daniel" (PDF). Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. subscription site. 56: 115. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- Dougherty, Raymond Philip (1929). Nabonidus and Belshazzar: A Study of the Closing Events of the Neo- Babylonian Empire. Yale University Press. p. 216. ASIN B000M9MGX8.

- Eisenman, Robert (1998). James, the brother of Jesus : the key to unlocking the secrets of early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-025773-X.

- Ford, Desmond (1978). Daniel. Southern Publishing Association. p. 309. ISBN 0-8127-0174-7.

- Evans, Craig A.; Flint, Peter W. (1997). Eschatology, messianism, and the Dead Sea scrolls. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8028-4230-5.

- Goldingay, John (1989). Daniel (Word Biblical Themes) (Rich text format of book). Dallas: Word Publishing Group. p. 132. ISBN 0-8499-0794-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2008). "Chapter 16: Israel from the Rise of Hellenism to 70 CE". In Rogerson, John William; Lieu, Judith. The Oxford handbook of biblical studies (Google On-line Books). USA: Oxford University Press. p. 920. ISBN 0-19-923777-8.

- Godwin, compiled and translated by Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie ; with additional translations by Thomas Taylor and Arthur Fairbanks, Jr. ; introduced and edited by David R. Fideler ; with a foreword by Joscelyn (1987). The Pythagorean sourcebook and library : an anthology of ancient writings which relate to Pythagoras and Pythagorean philosophy ([New ed.] ed.). Grand Rapids: Phanes Press. ISBN 978-0-933999-51-0.

- Louis F. Hartman and Alexander A. Di Lella, "Daniel", in Raymond E. Brown et al., ed., The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, 1990, pp. 406–20.

- Hoppe, Leslie J. (1992). "Deuteronomy". In Bergant, Dianne. The Collegeville Bible commentary: based on the New American Bible: Old Testament (Google On-line Books). Liturgical Press. p. 464. ISBN 0-8146-2211-9. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- Keil, C. F.; Delitzsch, Franz (2006) [1955]. Ezekiel and Daniel. Commentary on the Old Testament. 9. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 0-913573-88-4.

- Longman III, Tremper; Dillard, Raymond B. (2006) [1995]. An Introduction to the Old Testament (2nd ed.). Zonderman. p. 528.

- Lucas, Ernest (2002). Daniel. Leicester, England: Apollos. ISBN 0-85111-780-5.

- Millard, Alan R. (1977). "Daniel 1–6 and History" (PDF). Evangelical Quarterly. Paternoster. 49 (2, April–June): 67–73. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- Miller, Stephen B. (1994). Daniel. New American Commentary. 18. Nashville: Broadman and Holman. p. 348. ISBN 0-8054-0118-0.

- Murphy, Frederick James (1998). Fallen is Babylon: the Revelation to John (Google On-line Books). Trinity Press International. p. 472. ISBN 1-56338-152-4. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- Notes (1992). The New American Bible. Catholic Book Publishing Co. p. 1021. ISBN 978-0-89942-510-8.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (1966). "Babylonian and Assyrian Historical Texts". In James B. Pritchard. Ancient Near Eastern Texts (2nd ed.; 3rd print ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 308.

- Rowley, H. H. (1959). Darius the Mede and the Four World Empires in the Book of Daniel: A Historical Study of Contemporary Theories. University of Wales Press. p. 195. ISBN 1-59752-896-X.

- Rowley, Harold Henry (1963). The Growth of the Old Testament. Harper & Row.

- Schwartz, Daniel R. (1992). Studies in the Jewish background of Christianity (Google On-line Books). Mohr Siebeck. p. 304. ISBN 3-16-145798-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Shea, William H. (1982). "Nabonidus, Belshazzar, and the Book of Daniel: An Update" (PDF). AUSS Journal Online Archive. Andrews University Seminary. 20 (2): 133–149. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- Shea, William H. (1986). "The Prophecy of Daniel 9:24–27". In Holbrook, Frank. The Seventy Weeks, Leviticus, and the Nature of Prophecy. Daniel and Revelation Committee Series. 3. Review and Herald Publishing Association.

- Steinberg, Martin H. Manser ; associate editors, David Barratt, Pieter J. Lalleman, Julius Steinberg (2009). Critical companion to the Bible : a literary reference. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-7065-7.

- Stimilli, Davide (2005). The face of immortality : physiognomy and criticism. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6263-8.

- Tyndale; Elwell, Walter A.; Comfort, Philip W. (2001). Tyndale Bible dictionary. Wheaton, Ill.: Tyndale House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8423-7089-9.

- Tomasino, Anthony J. (2003). Judaism before Jesus: the ideas and events that shaped the New Testament world. IVP Academic; Print On Demand Edition. p. 345. ISBN 0-8308-2730-7. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- Wiseman, D. J. (1965). Notes on Some Problems in the Book of Daniel. London: Tyndale Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-85111-038-X.

- Young, Edward J. (2009) [1949]. The Prophecy of Daniel: a Commentary. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 332. ISBN 0-8028-6331-0.

- John F. Walvoord, Daniel: The Key to Prophetic Revelation, 1989. ISBN 0-8024-1753-1.

- Ford, Desmond (1978). Daniel. Southern Publishing Association. p. 309. ISBN 0-8127-0174-7.

- Holbrook, Frank B., ed. (1986). Symposium on Daniel. Daniel & Revelation Committee Series. 2. Biblical Research Institute: Review and Herald Publishing Association. p. 557. ISBN 0-925675-01-6.

- Pfandl, Gerhard (2004). Daniel: The Seer of Babylon. Review and Herald Pub Assoc. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8280-1829-6.

- Stefanovic, Zdravko (2007). Daniel: Wisdom to the Wise: Commentary on the Book of Daniel. Pacific Press Publishing Association. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-8163-2212-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Book of Daniel. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Book of Daniel |

- Jewish translations

- Daniel (Judaica Press) * translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations

- Bible, King James Version,[1] Book of Daniel

- Daniel at The Great Books * (New Revised Standard Version)

- The Book of Daniel * (Full text from St-Takla.org, also available in Arabic)

- Daniel: 2013 Critical Translation with Audio Drama at biblicalaudio

- Daniel an introduction

-

Bible: Daniel public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Bible: Daniel public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

- Related articles

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Daniel

- Daniel: Wise Man and Visionary, by Elias Bickerman

- Aramaic of Daniel, Patrick Henry College

| Book of Daniel | ||

| Preceded by Esther |

Hebrew Bible | Succeeded by Ezra-Nehemiah |

| Preceded by Ezekiel |

Christian Old Testament |

Succeeded by Hosea |

- ↑ "Bible, King James Version". quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-17.