Anne Morrow Lindbergh

| Anne Morrow Lindbergh | |

|---|---|

Anne Spencer Morrow, 1918 | |

| Born |

Anne Spencer Morrow June 22, 1906 Englewood, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died |

February 7, 2001 (aged 94) Passumpsic, Vermont, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Smith College |

| Occupation | Author, aviator |

| Spouse(s) | Charles Lindbergh |

| Children |

Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr. (d. 1932) Jon Lindbergh Land Lindbergh Anne Lindbergh (d. 1993) Scott Lindbergh Reeve Lindbergh[1] |

| Parent(s) |

Dwight Whitney Morrow Elizabeth Cutter Morrow |

| Awards | Hubbard Medal (1934) |

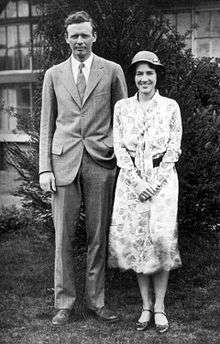

Anne Spencer Lindbergh (née Morrow; June 22, 1906 – February 7, 2001) was an American author, aviator, and the wife of aviator Charles Lindbergh.[2]

She was an acclaimed author whose books and articles spanned the genres of poetry to nonfiction, touching upon topics as diverse as youth and age, love and marriage, peace, solitude and contentment, and the role of women in the 20th century.[3] Lindbergh's Gift from the Sea is a popular inspirational book, reflecting on the lives of American women.

Early life

Anne Spencer Morrow was born on June 22, 1906 in Englewood, New Jersey.[4] Her father was Dwight Morrow, a partner in J.P. Morgan & Co., who became United States Ambassador to Mexico and United States Senator from New Jersey. Her mother, Elizabeth, was a poet and teacher, active in women's education,[1] who served as acting president of her alma mater Smith College.[2]

Anne was the second of four children; her siblings were Elisabeth Reeve,[5] Dwight, Jr., and Constance. The children were raised in a Calvinist household that fostered achievement.[6] Every night, Morrow's mother would read to her children for an hour. The children quickly learned to read and write, began reading to themselves, and writing poetry and diaries. Anne would later benefit from that routine, eventually publishing her later diaries to critical acclaim.[7]

After graduating from The Chapin School in New York City in 1924, where she was president of the student body, she attended Smith College from which she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1928.[2][8]

She received the Elizabeth Montagu Prize, for her essay on women of the 18th century such as Madame d'Houdetot, and the Mary Augusta Jordan Literary Prize, for her fictional piece "Lida Was Beautiful."[9]

Marriage and family

Morrow and Lindbergh met on December 21, 1927, in Mexico City.[10] Her father, Lindbergh's financial adviser at J. P. Morgan and Co., invited him to Mexico to advance good relations between it and the United States.[11]

At the time, Morrow was a shy 21-year-old senior at Smith College. Lindbergh was a courageous aviator whose solo flight across the Atlantic made him a hero of mythic proportions and the most famous man in the world.[8] Still, the sight of the boyish aviator, who was staying with the Morrows, tugged at Morrow's heartstrings. She would later write in her diary:

| “ | He is taller than anyone else—you see his head in a moving crowd and you notice his glance, where it turns, as though it were keener, clearer, and brighter than anyone else's, lit with a more intense fire.... What could I say to this boy? Anything I might say would be trivial and superficial, like pink frosting flowers. I felt the whole world before this to be frivolous, superficial, ephemeral.[10] | ” |

They were married in a private ceremony on May 27, 1929, at the home of her parents in Englewood, New Jersey.[12]

That year, Lindbergh flew solo for the first time, and in 1930, she became the first American woman to earn a first-class glider pilot's license. In the 1930s, both together explored and charted air routes between continents.[13] The Lindberghs were the first to fly from Africa to South America and explored polar air routes from North America to Asia and Europe.[14]

Their first child, Charles Jr, was born on Anne's 24th birthday, June 22, 1930.[15]

Kidnapping

In an incident widely known as the "Lindbergh kidnapping," the Lindberghs' first child, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., was kidnapped at 20 months of age from their home, Highfields, in East Amwell, New Jersey outside Hopewell on March 1, 1932.[lower-alpha 1]

After a massive investigation, a baby's body, presumed to be that of Charles Lindbergh Jr., was discovered the following May 12, some 4 mi (6 km) from the Lindberghs' home, at the summit of a hill on the Hopewell–Mt. Rose Highway.[17]

Exile

The frenzied press attention paid to the Lindberghs, particularly after the kidnapping of their son and later the trial, conviction, and execution of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, prompted them to retreat to England, to a house called Long Barn owned by Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West, and later to the small island of Illiec, off the coast of Brittany in France.[18]

Lindberghs and Nazi Germany

While in Europe, the Lindberghs came to advocate isolationist views that led to their fall from grace in the eyes of many. In 1938, the U.S. Air Attaché in Berlin invited Charles to inspect the rising power of Nazi Germany's Air Force. Impressed by German technology and their apparent number of aircraft and influenced by the staggering number of deaths from World War I, Charles opposed U.S. entry into the impending European conflict. He suggested any military assistance to Britain might be done for improper financial reasons: "To those who argue that we could make a profit and build up our own industry by selling munitions abroad, I reply that we in America have not yet reached a point where we wish to capitalize on the destruction and death of war."[19]

Lindbergh elucidated his beliefs about race in a Reader's Digest article in 1939: We can have peace and security only so long as we band together to preserve that most priceless possession, our inheritance of European blood, only so long as we guard ourselves against attack by foreign armies and dilution by foreign races.[20] Lindbergh's speeches and writings reflected the influence of Nazi views on race and religion. He wrote in his memoirs that all of the Germans he met thought the country would be better off without its Jews. [21]

Anne wrote a 41-page booklet, The Wave of the Future, published in 1940, in support of her husband who was lobbying for a U.S.-German peace treaty similar to Hitler's Non-Aggression Treaty with Joseph Stalin.[22] It argued that something resembling fascism was the unfortunate "wave of the future" and echoed echoing authors such as Lawrence Dennis and later James Burnham.[23]

The Roosevelt administration subsequently attacked The Wave of the Future as "the bible of every American Nazi, Fascist, Bundist and Appeaser," and the booklet became one of the most despised writings of the period.[24][25] She had also written in a letter, of Hitler, that he was "a very great man, like an inspired religious leader—and as such rather fanatical—but not scheming, not selfish, not greedy for power."[25]

Return to U.S.

In April 1939, the Lindberghs returned to the United States. Because of his outspoken beliefs about a future war that would envelop their homeland, the antiwar America First Committee quickly adopted Charles as its leader in 1940.[11] After the attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany's declaration of war, the committee disbanded, and he eventually managed to become involved in the military and enter combat only as a civilian.[26][27]

In this period, Anne met the famous French writer, poet and pioneering aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of the famous novella The Little Prince, and the two had a secret affair.[28]

The Lindberghs had five more children: sons Jon, Land and Scott, and daughters Anne and Reeve.[29][30]

Later life

After the war, she wrote books that helped to rebuild the reputations they had gained and lost before World War II. The publication of Gift from the Sea in 1955 earned her place as "one of the leading advocates of the nascent environmental movement" and became a national best seller.[31]

Over the course of their 45-year marriage, the Lindberghs lived in New Jersey, New York, England, France, Maine, Michigan, Connecticut, Switzerland, and Hawaii. Charles died on Maui in 1974. Anne had a three-year affair in the early 1950s with her personal doctor.[32]

In her later life, Anne never suspected that according to Rudolf Schröck, author of Das Doppelleben des Charles A. Lindbergh (Heyne Verlag, 2005), from 1957 until his death in 1974, Charles led a double life. An affair from 1957 with Brigitte Hesshaimer produced three children whom he supported financially. In 2003, after Brigitte's passing, DNA tests conducted by the University of Munich proved conclusive.[33] Schröck claims Brigitte's, sister Marietta, also bore him two sons, and his former private secretary, two more children. A family reconciliation with the German family members later took place with Reeve Lindbergh being actively involved.[34]

After suffering a series of strokes in the early 1990s, which left her confused and disabled, she continued to live in her home in Connecticut with the assistance of round-the-clock caregivers. During a visit to her daughter Reeve's family in 1999, she came down with pneumonia, after which she went to live near Reeve in a small home built on Reeve's Passumpsic, Vermont, farm, where Anne died in 2001 at 94, following another stroke. Reeve Lindbergh's book, No More Words, tells the story of her mother's last years.[35]

Honors and awards

Anne received numerous honors and awards throughout her life in recognition of her contributions to both literature and aviation. In 1933, she received the U.S. Flag Association Cross of Honor for having taken part in surveying transatlantic air routes. The following year, she was awarded the Hubbard Medal by the National Geographic Society for having completed 40,000 miles (64,000 km) of exploratory flying with her husband, Charles Lindbergh, a feat that took them to five continents. In 1993, Women in Aerospace presented her with an Aerospace Explorer Award in recognition of her achievements in and contributions to the aerospace field.[1][12]

She was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame (1979), the National Women's Hall of Fame (1996), the Aviation Hall of Fame of New Jersey, and the International Women in Aviation Pioneer Hall of Fame (1999).[1]

Her first book, North to the Orient (1935) won one of the inaugural National Book Awards: the Most Distinguished General Nonfiction of 1935, voted by the American Booksellers Association.[36][37]

Her second book, Listen! The Wind (1938), won the same award in its fourth year[38] after the Nonfiction category had subsumed Biography. She received the Christopher Award for War Within and Without, the last installment of her published diaries.[39]

In addition to being the recipient of honorary master's and doctor of letters degrees from her alma mater Smith College (1935 and 1970), Anne received honorary degrees from Amherst College (1939), the University of Rochester (1939), Middlebury College (1976), and Gustavus Adolphus College (1985).[40]

Bibliography

- North to the Orient. Orlando, Florida: Mariner Books, 1996, First edition 1935. ISBN 978-0-15-667140-8.

- Listen! The Wind. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1990, First edition 1938.

- The Wave of the Future: A Confession of Faith. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1940.

- The Steep Ascent. New York: Dell, 1956, First edition, 1944.

- Gift from the Sea. New York: Pantheon, 1991, First edition 1955. ISBN 978-0-679-73241-9.

- The Unicorn and Other Poems 1935–1955. New York: Pantheon, 1993, First edition 1956. ISBN 978-0-679-42540-3.

- Dearly Beloved Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2003, First edition 1962. ISBN 978-1-55652-490-5.

- Earth Shine. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1969.

- Bring Me a Unicorn: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1922–1928. Orlando, Florida: Mariner Books, 1973, First edition 1971. ISBN 978-0-15-614164-2.

- Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead: Diaries And Letters Of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1929–1932. Orlando, Florida: Mariner Books, 1993, First edition 1973. ISBN 978-0-15-642183-6.

- Locked Rooms and Open Doors: Diaries And Letters Of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1933–1935. Orlando, Florida: Mariner Books, 1993, First edition 1974. ISBN 978-0-15-652956-3.

- The Flower and the Nettle: Diaries And Letters Of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1936–1939. Orlando, Florida: Mariner Books, 1994, First edition 1976. ISBN 978-0-15-631942-3.

- War Without and Within: Diaries And Letters Of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 1939–1944. Orlando, Florida: Mariner Books, 1995, First edition 1980. ISBN 978-0-15-694703-9.

- Against Wind and Tide. Published posthumously by Anne Morrow Lindbergh's family in 2013, the final volume of diaries and letters spans the 1980s to the early 2000s.

References

Notes

- ↑ While the world's attention was focused on Hopewell from which the first press dispatches emanated about the kidnapping, The Hunterdon County Democrat made sure its readers knew that the new home of Col. Charles A. Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh was in East Amwell Township Hunterdon County.[16]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 "Anne Morrow Lindbergh Biography." Archived November 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Lindbergh Foundation. Retrieved: November 17, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Anne Morrow Lindbergh." Biography.com." Retrieved: November 17, 2011.

- ↑ Plunket, Robert. "The lives they lived: Anne Morrow Lindbergh, b. 1906; The Heroine." The New York Times, December 30, 2001. Retrieved: November 19, 2012.

- ↑ Hertog 2000, p. 50.

- ↑ "Elisabeth Morrow School, The - History and Philosophy". www.elisabethmorrow.org. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- ↑ Eakin, Emily (December 12, 1999). "The Pilot's Wife". The New York Times.

- ↑ Hertog 2000, p. 61.

- 1 2 Pace, Eric. "Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 94, dies; Champion of flight and women's concerns." The New York Times, February 8, 2001. Retrieved: November 17, 2011.

- ↑ Hertog 2000, p. 74.

- 1 2 Lindbergh 1971, p. 118.

- 1 2 Jennings and Brewster 1998, p. 420.

- 1 2 "Anne Morrow Lindbergh Biography Timeline." Charles Lindbergh. Retrieved: November 17, 2011.

- ↑ Lindbergh 1935, pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Hertog 2000, p. 141.

- ↑ Douglas and Olshaker 2001, p. 121.

- ↑ Gill, Barbara. "Lindbergh kidnapping rocked the world 50 years ago." The Hunterdon County Democrat, 1981.

- ↑ Lyman, Lauren D. "Press calls for action: Hopes the public will be roused to wipe out a 'national disgrace'." The New York Times, December 24, 1935, p. 1.

- ↑ Winters 2006, p. 193.

- ↑ October 13, 1939 speech excerpted in CharlesLindbergh.com

- ↑ Lindbergh, Charles. "Aviation, Geography, and Race|." Racial Nationalist Library. Retrieved: February 25, 2015.

- ↑ Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles Lindbergh

- ↑ Plunket, Robert. "The Lives They Lived: Anne Morrow Lindbergh, B. 1906: The Heroine." The New York Times, December 30, 2001.

- ↑ Lindbergh 1976, p. 224.

- ↑ Batten, Geoffrey. "Obituary: Anne Morrow Lindbergh." The Independent, February 15, 2001.

- 1 2 Pace, Eric. "Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Author and Aviator, Dies at 94." The New York Times, February 8, 2001.

- ↑ "Charles Lindbergh in Combat, 1944." EyeWitness to History, 2006. Retrieved: July 20, 2009.

- ↑ Mersky 1983, p. 93.

- ↑ "Anne Lindbergh: Anne Morrow Lindbergh, a hero’s co-pilot, died on February 7th, aged 94." The Economist, February 15, 2001. Retrieved: January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Green, Penelope. "But Enough About Them." The New York Times, April 17, 2008.

- ↑ Hertog 2000, p. 24.

- ↑ "Anne Morrow Lindbergh." PBS. Retrieved: November 17, 2011.

- ↑ Connelly, Sherryl. "HERO WORSHIP: Anne Morrow Lindbergh emerges from Lindy's shadow in new biography." New York Daily News, December 12, 1999. Retrieved: November 21, 2011.

- ↑ "DNA Proves Lindbergh Led a Double Life." The New York Times, November 29, 2003. Retrieved: November 21, 2011.

- ↑ Schröck, Rudolf. "The Lone Eagle’s Clandestine Nests: Charles Lindbergh’s German secrets." Archived May 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. The Atlantic Times, June 2005. Retrieved: September 16, 2010.

- ↑ Lindbergh, Reeve 2002, p. 175.

- ↑ "Books and Authors". The New York Times, April 12, 1936, page BR12 via ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851–2007).

- ↑ "Lewis is Scornful of Radio Culture: ...", The New York Times, May 12, 1936, p. 25 via ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851–2007).

- ↑ "Book About Plants Receives Award: Dr. Fairchild's 'Garden' Work Cited by Booksellers". The New York Times, February 15, 1939, p. 20 via ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851–2007).

- ↑ "Anne Morrow Lindbergh." The American Experience: Lindbergh PBS, 2009. Retrieved: November 20, 2011.

- ↑ Hertog 2000, pp. 240, 274.

Bibliography

- Berg, A. Scott. Lindbergh. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1998. ISBN 0-399-14449-8.

- Douglas, John E. and Mark Olshaker. The Cases That Haunt Us. New York: Pocket Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0-6710-1706-4.

- Hertog, Susan Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life. New York: Anchor, 2000. ISBN 978-0-385-72007-6.

- Jennings, Peter and Todd Brewster. The Century. New York: Doubleday, 1998. ISBN 0-385-48327-9.

- Lindbergh, Reeve. No More Words: A Journal of My Mother, Anne Morrow Lindbergh. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 0-7432-0314-3.

- Mersky, Peter B. U.S. Marine Corps Aviation – 1912 to the Present. Annapolis, Maryland: Nautical and Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1983. ISBN 0-933852-39-8.

- Milton, Joyce. Loss of Eden: A Biography of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh. New York: Harper Collins, 1993. ISBN 0-06-016503-0.

- Mosley, Leonard. Lindbergh: A Biography. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1976. ISBN 978-0-38509-578-5.

- Winters, Kathleen. Anne Morrow Lindbergh: First Lady of the Air. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 1-4039-6932-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anne Morrow Lindbergh. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anne Morrow Lindbergh |

- Anne Morrow Lindbergh at PBS

- Anne Morrow Lindbergh Papers at the Sophia Smith Collection

- The Lindbergh Foundation - Anne Morrow Lindbergh

- Anne Morrow Lindbergh at Find a Grave

- Death of Dwight Morrow

- Dwight Morrow's Will

- Morrow's Estate Value

- Descendants of Thomas Hastings website