Anna Leopoldovna

| Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regent of Russia | |||||

.jpg) | |||||

| Reign | 1740–1741 | ||||

| Born |

18 December 1718 Rostock | ||||

| Died |

19 March 1746 (aged 27) Kholmogory | ||||

| Burial | Alexander Nevsky Monastery | ||||

| Spouse | Duke Anthony Ulrich of Brunswick | ||||

| Issue among others... | Ivan VI of Russia | ||||

| |||||

| House | Mecklenburg-Schwerin | ||||

| Father | Charles Leopold, Duke of Mecklenburg | ||||

| Mother | Catherine Ivanovna of Russia | ||||

| Religion |

Eastern Orthodox prev. Lutheranism | ||||

Anna Leopoldovna (Russian: А́нна Леопо́льдовна; 18 December 1718 – 19 March 1746), born as Elisabeth Katharina Christine von Mecklenburg-Schwerin and also known as Anna Carlovna[1] (А́нна Ка́рловна), was regent of Russia for a few months in 1740 and 1741 during the minority of her infant son Emperor Ivan VI.

Biography

Elisabeth Katharina Christine was the daughter of Catherine, the sister of the Russian empress Anna, and of Karl Leopold, the duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.[2] Catherine separated from Elisabeth's father and the two escaped to Russia in 1722. Catherine was considered for the imperial throne in 1730 but her sister Anna was chosen instead. In 1733, Elisabeth converted to the Russian Orthodox Church and given the name Anna Leopoldovna, which made her acceptable as an heir to the throne. In 1739, she married Anthony Ulrich (1714–1776), son of Ferdinand Albert, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel.[2] He had lived in Russia since 1733 so that she could get to know him.

On 5 October 1740, the empress Anna adopted their newborn son Ivan and proclaimed him heir to the Russian throne.[1] On 28 October, just a few weeks after this proclamation, the empress died, leaving directions regarding the succession and appointing her favourite Ernest Biron, Duke of Courland, as regent.[1]

Biron, however, had made himself an object of detestation to the Russian people.[1] After Biron threatened to exile Anna and her spouse to Germany, she had little difficulty working with Field Marshal Burkhard Christoph von Münnich to overthrow him.[1] The coup succeeded and she assumed the regency on 8 November, taking the title of Grand Duchess. Field Marshal Münnich personally arrested Biron in his apartment, where the formerly tyrannical Biron ingloriously begged for his life on his knees.[3] She knew little of the character of the people with whom she had to deal, knew even less of the conventions and politics of Russian government, and speedily quarrelled with her principal supporters.[1]

According to the Dictionary of Russian History, she ordered an investigation of the garment industry when new uniforms received by the military were found to be of inferior quality. When the investigation revealed inhuman conditions she issued decrees mandating a minimum wage and maximum working hours in that industry as well as the establishment of medical facilities at every garment factory. She also presided over a brilliant victory by Russian forces at the Battle of Villmanstrand in Finland after Sweden had declared war against her Government. She had an influential favourite, Julia von Mengden. Anna's love life took up much of time as the bisexual Anna was involved simultaneously in what were described as "passionate" affairs with the Saxon ambassador Court Mozritz zu Lynar and her lady-in-waiting Mengden.[4] Anna's weak-willed husband did his best to ignore the affairs.[5] After becoming Regent, Anton was marginalized, being forced to sleep in another palace while Anna took either Lynar, Mengden or both to bed with her.[6] At times the grand duke would appear to complain about cuckolded, but he was always sent away.[7] At one point, Anna proposed to have Lynar marry Mengden in order to the unite the two people closest to her in the world together.[8] The regent's relationship with Mengden caused much disgust in Russia, through the French historian Henri Troyat wrote that amongst the many libertines of St. Petersburg Anna's "sexual eclecticism" in having both a man and a woman as her lovers was seen as a sign of Anna's open-mindedness.[9] More damagingly, many in the Russian elite believed that at the age of twenty-two that Anna was too young and immature to be the Regent of Russia and that her preoccupation with her relationships with Lynar and Mengden at the expense of governing Russia made her a danger to the state.[10] Troyat described Anna as an "indolent day-dreamer" who only got up in the afternoon as she spent her mornings reading novels in bed and liked to wander around her apartment barely dressed and her hair undone in the afternoon with again reading novels her principle interest.[11] Anna's preference for handing out government jobs to Baltic German aristocrats caused much resentment on the part of the ethnic Russian nobility who not for the first nor last time complained that a disproportionate number of Baltic Germans were holding high office.[12]

In December 1741, Elizabeth, the daughter of Peter the Great, excited the guards to revolt, having already become a favorite of theirs.[1] The coup overcame the insignificant opposition and was supported by the ambassadors of France and Sweden, owing to the pro-British and pro-Austrian policies of Anna's government. The French ambassador in St. Petersburg, the marquis de La Chétardie was deeply involved in planning Elizabeth's coup and bribed numerous officers of the Imperial Guard into supporting the coup.[13]

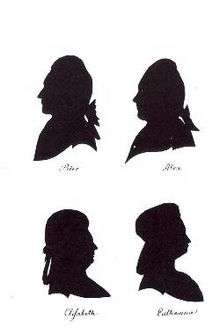

The victorious regime first imprisoned the family in the fortress of Dünamünde near Riga and then exiled them to Kholmogory on the Northern Dvina river. Anna eventually died on 18 March 1746 during childbirth.[2] Her son Ivan VI was murdered in Shlisselburg on 16 July 1764, while her husband Anthony Ulrich died in Kholmogory on 19 March 1776. Her remaining four children (Ekaterina, Elizaveta, Peter and Alexei[14]) were released from prison into the custody of their aunt, the Danish queen dowager Juliana Maria of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, on 30 June 1780 and settled in Jutland, where they lived in comfort under house arrest in Horsens for the rest of their lives under the guardianship of Juliana and at the expense of Catherine the Great: having lived as prisoners, they were not used to social life, and kept a small "court" of 40/50 people, all Danish except for the priest.[15]

Family

.jpg)

Anna Leopoldovna had the following children:

- Ivan VI (1740–1764) (reigning Emperor 1740-1741)

- Catherine Antonovna of Brunswick (1741–1807) (released to house arrest in Horsens in Denmark in 1780)

- Elizabeth Antonovna of Brunswick (1743–1782) (released to house arrest in Horsens in Denmark in 1780)

- Peter Antonovich of Brunswick (1745–1798) (released to house arrest in Horsens in Denmark in 1780)

- Alexei Antonovich of Brunswick (1746–1787) (released to house arrest in Horsens in Denmark in 1780)

Titles and styles

- 18 December 1718 – 3 July 1739: Her Serene Highness Duchess Elisabeth of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- 3 July 1739 – 8 November 1740: Her Serene Highness Duchess Elisabeth of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- 8 November 1740 – 6 December 1741: Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna, Regent of Russia

- 6 December 1741 – 19 March 1746: Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna of Russia

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Anna Leopoldovna | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 EB (1878).

- 1 2 3 EB (1911).

- ↑ Moss, Walter A History of Russia Volume I, Boston: MacGraw-Hill, 2001 page 255.

- ↑ Moss, Walter A History of Russia Volume I, Boston: MacGrawHill, 2001 page 254.

- ↑ Moss, Walter A History of Russia Volume I, Boston: MacGrawHill, 2001 page 254.

- ↑ Troyat, Henri Terrible Tsarinas: Five Russian Women in Power, New York: Algora Publishing, 2000 page 99.

- ↑ Troyat, Henri Terrible Tsarinas: Five Russian Women in Power, New York: Algora Publishing, 2000 page 99.

- ↑ Troyat, Henri Terrible Tsarinas: Five Russian Women in Power, New York: Algora Publishing, 2000 page 101.

- ↑ Troyat, Henri Terrible Tsarinas: Five Russian Women in Power, New York: Algora Publishing, 2000 page 100.

- ↑ Moss, Walter A History of Russia Volume I, Boston: MacGrawHill, 2001 page 254.

- ↑ Troyat, Henri Terrible Tsarinas: Five Russian Women in Power, New York: Algora Publishing, 2000 page 99.

- ↑ Moss, Walter A History of Russia Volume I, Boston: MacGrawHill, 2001 page 254.

- ↑ Cowles, Virginia The Romanovs, London: William Collins, 1971 pages 67-68.

- ↑ Kamenskiĭ, Aleksandr Abramovich; Griffiths, David B. (1997). The Russian Empire in the Eighteenth Century: Tradition and Modernization from Peter to Catherine (The New Russian History). M.E. Sharpe. p. 164. ISBN 1-56324-575-2.

- ↑ Marie Tetzlaff : Katarina den stora (1998)

- Bibliography

- "Anna Carlovna", Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. II, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, p. 59.

- "Anna Leopoldovna", Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., Vol. II, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911, p. 60.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anna Leopoldovna. |

"Anna Carlovna". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Anna Carlovna". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Romanovs. The fourth film. Anna Ioannovna; Anna Leopoldovns; Elizabeth Petrovna on YouTube – Historical reconstruction "The Romanovs". StarMedia. Babich-Design(Russia, 2013)