National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

|

| |

| Drafted | February 2006 |

|---|---|

| Effective | Not in effect |

| Condition | Adoption by several of the states and including the District of Columbia whose collective electoral vote total represents an absolute majority of votes (at least 270) in the Electoral College. Note: The agreement would be in effect only among the assenting constituent political entities. |

| Signatories | |

|

| |

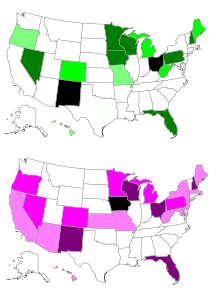

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is an agreement among a group of U.S. states and the District of Columbia to award all their respective electoral votes to whichever presidential candidate wins the overall popular vote in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The compact is designed to ensure that the candidate who wins the most popular votes is elected president, and it will come into effect only when it will guarantee that outcome.[2][3] As of 2016, it has been adopted by ten states and the District of Columbia. Together, they have 165 electoral votes, which is 30.7% of the total Electoral College and 61.1% of the votes needed to give the compact legal force.

Mechanism

Proposed in the form of an interstate compact, the agreement would go into effect among the participating states in the compact only after they collectively represent an absolute majority of votes (currently at least 270) in the Electoral College. In the next presidential election after adoption by the requisite number of states, the participating states would award all of their electoral votes to presidential electors associated with the candidate who wins the overall popular vote in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. As a result, the winner of the national popular vote would always win the presidency by always securing a majority of votes in the Electoral College. Until the compact's conditions are met, all states award electoral votes in their current manner.

The compact would modify the way participating states implement Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which requires each state legislature to define a method to appoint its electors to vote in the Electoral College. The Constitution does not mandate any particular legislative scheme for selecting electors, and instead vests state legislatures with the exclusive power to choose how to allocate its own electors.[3][4] States have chosen various methods of allocation over the years, with regular changes in the nation's early decades. Today, all but two states (Maine and Nebraska) award all their electoral votes to the candidate with the most votes statewide.

Motivation behind the compact

Because of current state laws, presidential candidates have lost the popular vote nationally but still won the presidency.[5] Public opinion surveys suggest that a majority of Americans support the idea of a popular vote for President. A 2007 poll found that 72% favored replacing the Electoral College with a direct election, including 78% of Democrats, 60% of Republicans, and 73% of independent voters.[6] Polls dating back to 1944 have shown a consistent majority of the public supporting a direct vote.[7] Reasons behind the compact include:

- The Electoral College allows a candidate to win the Presidency while losing the popular vote, as happened in the elections of 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016. In the 2000 election, the outcome was decided by a margin of 537 votes in Florida, despite a 543,895 difference in popular vote nationally.

- The Electoral College system effectively forces candidates to focus disproportionately on a small percentage of pivotal swing states, while sidelining the rest. A study by FairVote reported that the 2004 candidates devoted three quarters of their peak season campaign resources to just five states, while the other 45 states received very little attention. The report also stated that 18 states received no candidate visits and no TV advertising.[8] This means that swing state issues receive more attention, while issues important to other states are largely ignored.[9][10][11]

- The Electoral College system tends to decrease voter turnout in states without close races. Voters living outside the swing states have a greater certainty of which candidate is likely to win their state. This knowledge of the probable outcome decreases their incentive to vote.[9][11] A report by the Committee for the Study of the American Electorate found that 2004 voter turnout in competitive swing states grew by 6.3% from the previous presidential election, compared to an increase of only 3.8% in noncompetitive states.[12] A report by The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) found that turnout among eligible voters under age 30 was 64.4% in the 10 closest battleground states and only 47.6% in the rest of the country—a 17% gap.[13]

Debate

The project has been supported by editorials in newspapers, including The New York Times,[9] the Chicago Sun-Times, the Los Angeles Times,[14] The Boston Globe,[15] and the Minneapolis Star Tribune,[16] arguing that the existing system discourages voter turnout and leaves emphasis on only a few states and a few issues, while a popular election would equalize voting power. Others have argued against it, including the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.[17] An article by Pierre S. du Pont, IV, a former governor of Delaware, in the opinion section of The Wall Street Journal[18] has called the project an urban power grab that would shift politics entirely to urban issues in high population states and allow lower caliber candidates to run. A collection of readings pro and con has been assembled by the League of Women Voters.[19]

Some of the major points of debate are detailed below:

Campaign focus

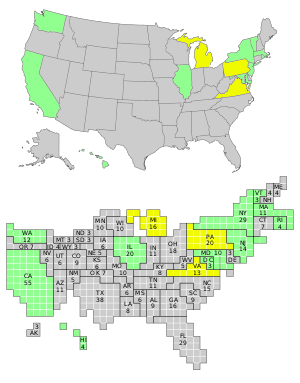

| Advertising spending and campaign visits by both major-party candidates during the final stretch of the 2004 presidential campaign (Sept. 26 – Nov. 2, 2004)[20]

Spending on advertising per capita:

Campaign visits per 1 million residents:

|

|

Under the current system, campaign focus – in terms of spending, visits, and attention paid to regional or state issues – is largely limited to the few swing states whose electoral outcomes are competitive, with politically "solid" states mostly ignored by the campaigns. The maps to the right illustrate the amount spent on advertising and the number of visits to each state, relative to population, by the two major-party candidates in the last stretch of the 2004 presidential campaign. Supporters of the compact contend that a national popular vote would encourage candidates to campaign with equal effort for votes in competitive and non-competitive states alike.[21] Critics of the compact argue that candidates would have less incentive to focus on states with smaller populations or fewer urban areas, and would thus be unmotivated to address rural issues.[18][22]

Close elections and election fraud

Opponents of the compact have raised concerns about election fraud. In his article, Pete du Pont argues that in 2000, "Mr. Gore's 540,000-vote margin amounted to 3.1 votes in each of the country's 175,000 precincts. 'Finding' three votes per precinct in urban areas is not a difficult thing...". However, National Popular Vote has argued that the large pool of 122 million votes spread across the country would make a close or fraudulent outcome much less likely than under the current system, in which the national winner may be determined by an extremely small vote margin in any one of the fifty-one statewide tallies.[18][22]

The NPVIC does not include any provision for a nationwide recount in the event that the vote tally is in dispute. While each state has established rules governing recounts in the event of a close or disputed statewide tally,[23] it is possible for the national vote to be close without there being a close result in any one state. Proponents of the compact argue that the need for a recount would be less likely under a national popular vote than under the current electoral system.[24]

Populous states versus low-population states

There is some debate over whether the Electoral College favors small- or large-population states. Those who argue that the College favors low-population states point out that such states have proportionally more electoral votes relative to their populations, because each state's number of electors is greater by two than its (proportionally allocated) number of Congressional representatives.[17][25] In the most populous state, California, this results in an electoral clout 16% smaller than a purely proportional allocation would produce, whereas the least-populous states, with three electors, hold a voting power 143% greater than they would under purely proportional allocation. The proposed compact would give equal weight to each voter's ballot, regardless of what state they live in. Others, however, believe that since most states award electoral votes on a winner-takes-all system, the potential of populous states to shift greater numbers of electoral votes gives them more actual clout.[26][27][28]

Possible partisan advantage

Some supporters and opponents of the NPVIC have based their position at least in part on a perceived partisan advantage of the compact. Former Delaware Governor Pierre S. du Pont IV, a Republican, has argued that the compact would be an "urban power grab" and benefit Democrats.[18] However, Saul Anuzis of the Republican National Committee wrote that Republicans "need" the compact, citing what he believes to be the center-right nature of the American electorate.[29] New Yorker essayist Hendrik Hertzberg maintains that the compact would benefit neither party, noting that historically both Republicans and Democrats have been successful in winning the popular vote in presidential elections.[30] In the last five presidential elections, the electoral vote system has favored Democrats in two -- 2008, and 2012[31] -- and favored Republicans in three -- 2000, 2004, and 2016.[32] In 2000 and 2016, Democrats won the popular vote but lost in the electoral college.[33]

Relevance of state-level majorities

Two governors who have vetoed NPVIC legislation, Arnold Schwarzenegger of California and Linda Lingle of Hawaii, both in 2007, objected to the compact on the grounds that it could require their states' electoral votes to be awarded to a candidate who did not win a majority in their state. (Both states have since enacted laws joining the compact.) Supporters of the compact counter that under a national popular vote system, state-level majorities are irrelevant; in any state, votes cast contribute to the nationwide tally, which determines the winner. The preferences of individual voters are thus paramount, while state-level majorities are an obsolete intermediary measure.[34][35][36]

Legality

Supporters believe the compact is legal under Article II of the U.S. Constitution, which establishes the plenary power of the states to appoint their electors in any manner they see fit: "Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress…" Proponents of this position include law professor Jamie Raskin (now U.S. Congressman-elect for Maryland's 8th congressional district), who, as a state legislator, co-sponsored the first NPVIC bill to be signed into law, and law professors Akhil Reed Amar and Vikram Amar, who were the compact's original proponents.[37]

A 2008 assessment by law school student David Gringer suggested that the NPVIC could potentially violate the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but the U.S. Department of Justice in 2012 precleared California's entry into the compact under Section 5 of the Act, concluding that the compact had no adverse impact on California's racial minority voters.[38][39] FairVote's Rob Richie says that the NPVIC "treats all voters equally."[40]

Gringer also assailed the NPVIC as "an end-run around the constitutional amendment process." Raskin has responded: "the term 'end run' has no known constitutional or legal meaning. More to the point, to the extent that we follow its meaning in real usage, the 'end run' is a perfectly lawful play."[41] Raskin argues that the adoption of the term "end run" by the compact's opponents is a tacit acknowledgment of the plan's legality.

Ian Drake, an assistant professor of Political Science and another critic of the compact, has argued that the constitution both requires and prohibits Congressional approval of the compact. In Drake's view, only a constitutional amendment could make the compact valid.[42] Authors Michael Brody,[43] Jennifer Hendricks,[44] and Bradley Turflinger[45] have examined the compact and concluded that the NPVIC, if successfully enacted, would pass constitutional muster. Brody has put forth a unique theory that the legality of the NPVIC could potentially hinge on the notion that faithless electors are not necessarily obligated to vote for the candidate to whom they are pledged.[46]

It is possible that Congress would have to approve the NPVIC before it could go into effect. Article I, Section 10 of the US Constitution states that: "No State shall, without the Consent of Congress . . . enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power." However, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled in Virginia v. Tennessee, 148 U.S. 503 (1893), and in several more recent cases, that such consent is not necessary except where a compact encroaches on federal supremacy.[47] Every Vote Equal argues that the compact could never encroach upon federal power since the Constitution explicitly gives the power of casting electoral votes to the states, not the federal government. Derek Muller argues that the NPVIC would nonetheless affect the federal system in such a way that it would require Congressional approval,[48] while Ian Drake argues that Congress is actually prohibited under the Constitution from granting approval to the NPVIC.[42] NPVIC supporters dispute this conclusion and state they plan to seek congressional approval if the compact is approved by a sufficient number of states.[49]

History

Proposals to abolish the Electoral college by amendment

Several proposals to abolish the Electoral College by constitutional amendment have been introduced in Congress over the decades. These efforts have, however, been hampered by the fact that a two-thirds vote in both the House and Senate are required to send an amendment to the states, where ratification by three-fourths of the State legislatures or by conventions in three fourths of the states is required for it to become operative.

Bayh–Celler Amendment

The amendment which came closest to success was the Bayh–Celler proposal during the 91st Congress (January 1969 – January 1971). Introduced by Representative Emanuel Celler of New York as House Joint Resolution 681, it would have replaced the Electoral College with a simpler plurality system based on the national popular vote. Under this system, the pair of candidates who had received the highest number of votes would win the presidency and vice presidency respectively, providing they won at least 40% of the national popular vote. If no pair received 40% of the popular vote, a runoff election would be held, in which the choice of president and vice president would be made from the two pairs of persons who had received the highest numbers of votes in the first election. The word "pair" was defined as "two persons who shall have consented to the joining of their names as candidates for the offices of President and Vice President."[50] Celler's proposed constitutional amendment passed in the House of Representatives by a 338–70 vote in 1969, but was filibustered in the Senate, where it died.

Every Vote Counts Amendment

A joint resolution to amend the Constitution, providing for the popular election of the president and vice president under a new electoral system was introduced in 2005 by Representative Gene Green of Texas. In 2009, at the start of the 111th Congress, Green introduced H

Academic plan

In 2001, Northwestern University law professor Robert Bennett suggested a plan in an academic publication to implement a National Popular Vote through a mechanism that would embrace state legislatures' power to appoint electors, rather than resist that power.[51] By coordinating, states constituting a majority of the Electoral College could effectively implement a popular vote.

Law professors (and brothers) Akhil Reed Amar and Vikram Amar defended the constitutionality of such a plan.[52] They proposed that a group of states, through legislation, form a compact wherein they agree to give all of their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner, regardless of the balance of votes in their own state. These state laws would only be triggered once the compact included enough states to control a majority of the electoral college (270 votes), thus guaranteeing that the national popular vote winner would also win the electoral college.

The academic plan uses two constitutional features:

- Presidential Electors Clause in Article 2, section 1, clause 2 which gives each state the power to determine the manner in which its electors are selected.

- Compact Clause, Article I, section 10, clause 3 under which it creates an enforceable compact.

The Amar brothers noted that such a plan could be enacted by the passage of laws in as few as eleven states and would probably not require Congressional approval, though this is not certain (see Debate above).

Organization and advocacy

In 2006, John Koza, a computer science professor at Stanford, was the lead author of Every Vote Equal, a book that makes a detailed case for his plan for an interstate compact to establish National Popular Vote.[53] (Koza had previously had exposure to interstate compacts from his work with state lottery commissions after inventing the scratch-off lottery ticket.) That year, Koza, Barry Fadem and others formed National Popular Vote, a non-profit group to promote the legislation. The group has a transpartisan advisory committee including former US Senators Jake Garn, Birch Bayh, and David Durenberger, and former Representatives John Anderson, John Buchanan, and Tom Campbell.

By the time of the group's opening news conference in February 2006, the proposed interstate compact had been introduced in the Illinois legislature. With backing from National Popular Vote, the NPVIC legislation was introduced in five additional state legislatures in the 2006 session. It passed in the Colorado Senate and in both houses of the California legislature before being vetoed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Adoption

In 2007, NPVIC legislation was introduced in 42 states. It was passed by at least one legislative chamber in Arkansas,[54] California,[55] Colorado,[56] Illinois,[57] New Jersey,[58] North Carolina,[59] Maryland, and Hawaii.[60] Maryland became the first state to join the compact when Governor Martin O'Malley signed it into law on April 10, 2007.[61]

New Jersey became the second state to enter the compact when Governor Jon S. Corzine signed the bill on January 13, 2008.[62] Illinois became the third state to join when Governor Rod Blagojevich signed it into law on April 7, 2008[57] and Hawaii became the fourth on May 1, 2008, after the legislature overrode a second veto from the governor.[63]

Washington became the fifth state to join when Governor Christine Gregoire signed it into law on April 28, 2009.[64] Massachusetts became the sixth state to join when Governor Deval Patrick signed it into law on August 4, 2010.[65] The District of Columbia entered into the compact when the bill was signed by Mayor Adrian Fenty on October 12, 2010. (Neither chamber of Congress objected to the passage of the bill during the mandatory review period of 30 legislative days following that date, thus allowing the District's action to proceed.)[66]

Vermont joined the compact when Governor Peter Shumlin signed it into law on April 22, 2011.[67] California entered the compact on August 8, 2011, with Governor Jerry Brown's signature.[68] Rhode Island entered the compact on July 12, 2013, with Governor Lincoln Chafee's signature.[69] On April 15, 2014, New York entered the compact with a bipartisan vote in the NY assembly and Governor Andrew Cuomo's signature.[70]

NPVIC legislation has been introduced in all 50 states.[1] States where only one chamber has adopted the legislation are Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Oregon. In Colorado the legislation has passed in both chambers (in different sessions). Bills seeking to repeal the compact in Maryland, New Jersey and Washington have failed.

| No. | Jurisdiction | Current Electoral votes (EV) | Date adopted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maryland | 10 | April 10, 2007 |

| 2 | New Jersey | 14 | January 13, 2008 |

| 3 | Illinois | 20 | April 7, 2008 |

| 4 | Hawaii | 4 | May 1, 2008 |

| 5 | Washington | 12 | April 28, 2009 |

| 6 | Massachusetts | 11 | August 4, 2010 |

| 7 | District of Columbia | 3 | December 7, 2010 |

| 8 | Vermont | 3 | April 22, 2011 |

| 9 | California | 55 | August 8, 2011 |

| 10 | Rhode Island | 4 | July 12, 2013 |

| 11 | New York | 29 | April 15, 2014 |

| Total | 165 (61.1% of the 270 EV needed) | ||

Prospects

Psephologist Nate Silver wrote that, as swing states are unlikely to support a compact that reduces their influence, the compact cannot succeed without adoption by "red states".[71] As of 2016, all the states that have adopted the compact are "blue states", ranking within the 14 strongest vote shares for Barack Obama in the 2012 Presidential Election.

Bills

Currently active bills

The table below lists state bills to join the NPVIC that are currently pending (as of November 9, 2016).[72] The "EVs" column indicates the number of electoral votes each state has.

| State | EVs | Session | Bill(s) | Lower house | Upper house | Executive | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

16 | 2015–16 | SB 88 | — | In committee[73] | — | Pending |

| |

20 | 2015–16 | HB 1542 | In committee[74] | — | — | Pending |

Bills in previous sessions

The table below lists the status of past bills that received a floor vote in at least one chamber of the state's legislature. Bills which failed without a floor vote are not listed. The "EVs" column indicates the number of electoral votes the state had at the time the bill was introduced. This number may have changed since then due to reapportionment after the 2010 Census.

| State | EVs | Session | Bill(s) | Lower house | Upper house | Executive | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2015–16 | HB 348 | Died in committee[75] | — | — | Failed | |

| 11 | 2016 | HB 2456, SB 1165 | Passed[76] | Died in committee[77] | — | Failed | |

| SB 1218 | — | Died in committee[78] | — | Failed | |||

| 6 | 2007 | HB 1703 | Passed[54] | Died in committee[54] | — | Failed | |

| 2009 | HB 1339 | Passed[79] | Died in committee[79] | — | Failed | ||

| 55 | 2005–06 | AB 2948 | Passed[80] | Passed[80] | Vetoed[80] | Failed | |

| 2007–08 | SB 37 | Passed[55] | Passed[55] | Vetoed[55] | Failed | ||

| 2011 | AB 459 | Passed[81] | Passed[81] | Signed[68] | Law | ||

| 9 | 2006 | SB 06-223 | Indef. postponed[82] | Passed | — | Failed | |

| 2007 | SB 07-046 | Indef. postponed[56] | Passed[56] | — | Failed | ||

| 2009 | HB 1299 | Passed[83] | Not voted on[83] | — | Failed | ||

| 7 | 2009 | HB 6437 | Passed[84] | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 2014 | HB 5126 | Passed committee, not voted on[85] | — | Failed | |||

| |

3 | 2009–10 | B18-0769 | Passed[86] | Signed[86] | Law | |

| 3 | 2009–10 | HB 198 | Passed[87] | Not voted on[87] | — | Failed | |

| 2011 | HB 55 | Passed[88] | Died in committee[88] | — | Failed | ||

| 4 | 2007 | HB 234,[89] SB 1956 | Did not override veto[60] | Overrode veto[60] | Vetoed[60] | Failed | |

| 2008 | HB 3013, SB 2898 | Overrode veto[90] | Overrode veto[63] | Vetoed[63] | Law | ||

| 21 | 2007–08 | HB 858,[91] HB 1685, SB 78 | Passed[57] | Passed[57] | Signed[57] | Law | |

| |

8 | 2012 | HB 1095, SB 705 | Failed[92] | Not voted on[93] | — | Failed |

| 4 | 2007–08 | LD 1744 | Indef. postponed[94] | Passed[95] | — | Failed | |

| 2013–14 | LD 511, S 201 | Failed 60–85[96] | Failed 17–17[96] | — | Failed | ||

| |

10 | 2007 | HB 148, SB 634 | Passed[97] | Passed[97] | Signed[97] | Law |

| 12 | 2007–08 | HB 4952, SB 445[98] | Passed[99] | Passed[100] | Not sent[101] | Failed | |

| 2009–10 | H 4156 | Passed[102] | Passed[103] | Signed | Law | ||

| |

17 | 2007–08 | HB 6610 | Passed 65–36[104] | Died in committee[104] | — | Failed |

| 10 | 2013–14 | HF799, SF585 | Failed 62–71[105] | Died in committee[106] | — | Failed | |

| 2015–16 | HF1171, SF3145 | Died in committee[107] | Died in committee[108] | — | Failed | ||

| 10 | 2015–16 | HB 1959, SB 1401 | Passed[109] | Died in committee[110] | — | Failed | |

| HB 2048 | Died in committee[111] | — | — | Failed | |||

| 3 | 2007 | SB 290 | — | Failed[112] | — | Failed | |

| 5 | 2014 | LB1058 | Passed committee, not voted on[113] | — | Failed | ||

| 2015-16 | LB112 | Indef. postponed[114] | — | Failed | |||

| |

5 | 2009 | AB 413 | Passed[115] | Died in committee | — | Failed |

| |

15 | 2006–07 | A 4225, S 2695 | Passed[58] | Passed[58] | Signed[58] | Law |

| |

5 | 2009 | HB 383 | Passed[116][117] | Not voted on[118] | — | Failed |

| 31 | 2010 | A1580B, S2286A | Not voted on[119] | Passed[119] | — | Failed | |

| 29 | 2011 | A00489, S4208 | Not voted on[120] | Passed[121] | — | Failed | |

| 2013 | A4422 | Passed[122] | Died in committee[122] | — | Failed | ||

| 2014 | A4422, S3149 | Passed[122] | Passed[123] | Signed[70] | Law | ||

| 15 | 2007–08 | H1645, S954 | Died in committee[124] | Passed[59] | — | Failed | |

| |

3 | 2007 | HB 1336 | Failed[125] | — | — | Failed |

| |

20 | 2008 | HB 524 | Died in committee[126] | — | — | Failed |

| 7 | 2014 | SB906 | Died in committee[127] | Passed[127] | — | Failed | |

| 2015-16 | HB1686 | — | Died in committee[128] | — | Failed | ||

| 7 | 2009 | HB 2588 | Passed[129] | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 2013 | HB 3077, SB 624 | Passed[130] | Died in committee[131] | — | Failed | ||

| 2015 | HB 3475 | Passed[132] | Died in committee[132] | — | Failed | ||

| 4 | 2008 | H 7707, S 2112 | Passed[133] | Passed[133] | Vetoed[133] | Failed | |

| 2009 | HB 5569, SB 161 | Failed[134][135] | Passed[134] | — | Failed | ||

| 2011 | HB 5659, SB 164 | Not voted on[136] | Passed[136] | — | Failed | ||

| 2013 | H 5575, S 346 | Passed[137] | Passed[137] | Signed[5] | Law[5] | ||

| 11 | 2015–16 | HB1728, SB1657 | Not voted on[138] | Not voted on[138] | — | Failed | |

| 3 | 2007–08 | H 373, S 270 | Passed[139] | Passed[139] | Vetoed[139] | Failed | |

| 2009–10 | S 34 | Died in committee[140] | Passed[140] | — | Failed | ||

| 2011–12 | S 31[141] | Passed[142] | Passed[142] | Signed[143] | Law | ||

| 11 | 2007–08 | HB 1750, SB 5628 | Died in committee[144] | Passed[145] | — | Failed | |

| 2009–10 | HB 1598, SB 5599 | Passed[146] | Passed[146] | Signed | Law | ||

See also

- National Popular Vote Inc.

- Electoral College (United States)

- FairVote

- Every Vote Counts Amendment

- Electoral reform in the United States

References

- 1 2 Progress in the States, National Popular Vote.

- ↑ "National Popular Vote". National Conference of State Legislatures. NCSL. March 11, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Brody, Michael (February 17, 2013). "Circumventing the Electoral College: Why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact Survives Constitutional Scrutiny Under the Compact Clause". Legislation and Policy Brief. Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. 5 (1): 33, 35. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ↑ McPherson v. Blacker 146 U.S. 1 (1892)

- 1 2 3 "RI joins national popular vote electoral compact". NBC10. 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation-Harvard University: Survey of Political Independents" (PDF). The Washington Post. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Americans Have Historically Favored Changing Way Presidents are Elected". Gallup. November 10, 2000. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Who Picks the President?". FairVote. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Drop Out of the College". The New York Times. March 14, 2006. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Electoral College is outdated". Denver Post. April 9, 2007. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- 1 2 Hill, David; McKee, Seth C. (2005). "The Electoral College, Mobilization, and Turnout in the 2000 Presidential Election". American Politics Research: 33:700–725. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Committee for the Study of the American Electorate" (PDF). November 4, 2004. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Lopez, Mark Hugo; Kirby, Emily; Sagoff, Jared (July 2005). "The Youth Vote 2004" (PDF). Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ "States Join Forces Against Electoral College". Los Angeles Times. June 5, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "A fix for the Electoral College". The Boston Globe. February 18, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "How to drop out of the Electoral College: There's a way to ensure top vote-getter becomes president". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. March 27, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- 1 2 "Electoral College should be maintained". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. April 29, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 du Pont, Pete (August 29, 2006). "Trash the 'Compact'". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ↑ "National Popular Vote Compact Suggested Resource List". Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Who Picks the President?" (PDF). FairVote. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ↑ "National Popular Vote". FairVote.

- 1 2 "National Popular Vote" (PDF). National Popular Vote. June 1, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Statewide Election Recounts, 2000-2009". FairVote.

- ↑ 3. Myths about Recounts, nationalpopularvote.com

- ↑ "David Broder, on PBS Online News Hour's Campaign Countdown". November 6, 2000. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Timothy Noah (December 13, 2000). "Faithless Elector Watch: Gimme "Equal Protection"". Slate.com. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Longley, Lawrence D.; Peirce, Neal (1999). Electoral College Primer 2000. Yale University Press. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

- ↑ Levinson, Sanford (2006). Our Undemocratic Constitution. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 28, 2008.

- ↑ Anuzis, Saul (May 26, 2006). "Anuzis: Conservatives need the popular vote". Washington Times. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ↑ Hertzberg, Hendrik (June 13, 2011). "Misguided "objectivity" on n.p.v". New Yorker. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ↑ Silver, Nate (November 8, 2012). "As Nation and Parties Change, Republicans Are at an Electoral College Disadvantage". The New York Times.

- ↑ In 2012, the tipping point state – which put the winner over 270 electoral votes – was Colorado, which voted Democratic by 5.4% (opposed to a 3.7% national margin), a 1.7% Democratic advantage. In 2008, the tipping point state was also Colorado, which voted Democratic by 8.9%, compared to a 7.2% national margin – a 1.7% Democratic advantage. In 2004, the tipping point state was Ohio, which voted Republican by 2.1%, compared to a national margin of 2.4% – a 0.3% Democratic advantage. In 2000, the tipping point state was (famously) Florida, which was effectively tied, while the nation voted Democratic by a 0.5% margin – a 0.5% Republican advantage.

- ↑ "These 3 Common Arguments For Preserving the Electoral College Are Wrong".

- ↑ SB-37, quoted on page 8

- ↑ "NewsWatch". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. April 24, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "What's Wrong With the Popular Vote?". Hawaii Reporter. April 11, 2007. Archived from the original on January 10, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Who Are the Top 20 Legal Thinkers in America?". Legal Affairs. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- ↑ Gringer, David (2008). "Why the National Popular Vote Plan Is the Wrong Way to Abolish the Electoral College" (PDF). Columbia Law Review. 108 (1). Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Letter" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. FairVote.

- ↑ Shane, Peter (May 16, 2006). "Democracy's Revenge? Bush v. Gore and the National Popular Vote". Moritz College of Law, Ohio State University. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ Raskin, Jamie (2008). "Neither the Red States nor the Blue States but the United States: The National Popular Vote and American Political Democracy" (PDF). Election Law Journal. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 7 (3): 188. doi:10.1089/elj.2008.7304. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- 1 2 Drake, Ian (September 20, 2013). "Federal Roadblocks: The Constitution and the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact". The Journal of Federalism. Oxford Journals.

- ↑ Circumventing the Electoral College: Why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact Survives Constitutional Scrutiny Under the Compact Clause

- ↑ "Popular Election of the President: Using or Abusing the Electoral College?".

- ↑ Turflinger, Bradley (2011). "Fifty Republics and the National Popular Vote: How the Guarantee Clause Should Protect States Striving for Equal Protection in Presidential Elections" (PDF). Valparaiso University Law Review. Valco Scholar. 45 (3): 793–843. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ↑ Circumventing the Electoral College: Why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact Survives Constitutional Scrutiny Under the Compact Clause

- ↑ "Background on Interstate Compacts" (PDF). Every Vote Equal (PDF). Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ↑ Muller, Derek T. (November 2007). "The Compact Clause and the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact". Election Law Journal. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 6 (4): 372–393. doi:10.1089/elj.2007.6403. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ↑ National Popular Vote Inc. "Interstate Compacts and Congressional Consent". Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Text of Proposed Amendment on Voting". The New York Times. April 30, 1969. p. 21.

- ↑ "Popular Election of the President Without a Constitutional Amendment".

- ↑ "How to Achieve Direct National Election of the President Without Amending the Constitution: Part Three Of A Three-part Series On The 2000 Election And The Electoral College". Findlaw. 2001. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ↑ "Count 'Em". New Yorker. March 6, 2006. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Arkansas". National Popular Vote, Inc. 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 "Complete Bill History (SB 37)". California Legislature. 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Summarized History for Bill Number SB07-046". Colorado Legislature. 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Bill Status of HB1685". Illinois General Assembly. 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bill Search (Bill A4225 from Session 2006–07)". New Jersey Legislature. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- 1 2 "Senate Bill 954". North Carolina. 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 "Hawaii SB 1956, 2007". Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Maryland sidesteps electoral college". MSNBC. April 11, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "New Jersey Rejects Electoral College". CBS News. CBS. January 13, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Hawaii SB 2898, 2008". Hawaii State Legislature. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Progress in the States". nationalpopularvote.com.

- ↑ "Progress in the States". nationalpopularvote.com.

- ↑ "Progress in the States". nationalpopularvote.com.

- ↑ "Progress in the States". nationalpopularvote.com.

- 1 2 "Office of Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. - Newsroom".

- ↑ "Progress in the States". nationalpopularvote.com.

- 1 2 <>

- ↑ Silver, Nate (17 April 2014). "Why a Plan to Circumvent the Electoral College Is Probably Doomed". FiveThirtyEight. ESPN. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ "Elections Legislation Database". National Conference of State Legislatures.

- ↑ "Senate Bill 88". Michigan Legislature. 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ↑ "HB 1542". Pennsylvania General Assembly. 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ↑ "HB 348". Alaska State Legislature. 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "House Bill 2456". Arizona State Legislature. 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Senate Bill 1165". Arizona State Legislature. 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ↑ "SB 1218". LegiScan. 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- 1 2 "Bill Status History". Arkansas State Legislature. 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Complete Bill History (AB 2948)". California Legislature. 2006. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- 1 2 "Complete Bill History: A.B. No. 459". California Legislature. 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Summarized History for Bill Number SB06-223". Colorado Legislature. 2006. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- 1 2 "Colorado Senate Kills National Popular Vote Bill". Ballot Access News. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ↑ "HB 6437". Connecticut General Assembly. 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ↑ "HB 5126". Connecticut General Assembly. 2014. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- 1 2 "Council of the District (Search for B18-0769)". Council of the District of Columbia. 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- 1 2 "House Bill No. 198". Delaware General Assembly. 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- 1 2 "House Bill No. 55". Delaware General Assembly. 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- ↑ "HB 234". Hawaii Legislature. 2007.

- ↑ "HB 3013". Hawaii Legislature. 2008. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Bill Status of HB0858". Illinois General Assembly. 2008.

- ↑ "HB 1095". Louisiana Legislature. 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ↑ "SB 705". Louisiana Legislature. 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Status of LD 1744". Maine Legislature. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Maine Senate passes National Popular Vote plan". Ballot Access News. April 2, 2008.

- 1 2 "Status of LD 511". Maine Legislature. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "House Bill 148". Maryland. 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Senate, No. 445". Massachusetts Legislature. 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "House, No. 4952". Massachusetts Legislature. 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Senate". Ballot-Access.org. 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ↑ Viser, Matt (August 1, 2008). "Legislature agrees to back Pike finances". The Boston Globe. Retrieved August 11, 2008. Although the bill passed both houses, the senate vote to send the bill to the governor did not take place before the end of the legislative session.

- ↑ "House, No. 4156". Massachusetts General Court. 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ↑ Andersen, Travis (July 16, 2010). "Winner-take-all bill is OK'd by state Senate". The Boston Globe.

- 1 2 "House Bill 6610 (2008)". Michigan Legislature. 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- ↑ "HF0799 Status in House for Legislative Session 88". 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ↑ "SF 585 Status in the Senate for the 88th Legislature (2013–2014)". 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ↑ "HF 1171". 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "SF 3145". 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "HB1959". Missouri House of Representatives. 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "SB 1041". Missouri Senate. 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "HB 2048". Missouri House of Representatives. 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Detailed Bill Information (SB290)". Montana Legislature. 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ "LB 1058 Status in Nebraska Legislature". 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LB112 - Adopt the Interstate Compact on the Agreement Among the States to Elect the President by National Popular Vote". Nebraska Legislature. 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "AB413". leg.state.nv.us.

- ↑ "HB383". New Mexico Legislature. 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ "New Mexico House Passes National Popular Vote Bill". ballot-access.org.

- ↑ "New Mexico Legislature Adjourns Without Passing National Popular Vote Plan". ballot-access.org.

- 1 2 "S02286-2009". New York Senate. 2010. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ "A00489 Summary". New York State Assembly. 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ↑ "S4208 Summary". New York State Assembly. 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "A04422 Summary". New York House. 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ "S03149 Summary". New York Senate. 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ "House Bill 1645". North Carolina General Assembly. 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ "Measure Actions". North Dakota State Government. 2007. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "House Bill Status Report of Legislation, 127th General Assembly, HB 524". Ohio Legislative Service Commission. 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- 1 2 "SB906 Status in Oklahoma Senate". Oklahoma Senate. 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Bill Information for HB 1686". Oklahoma Senate. 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Oregon Legislative Information System". olis.leg.state.or.us. Retrieved 2016-07-04.

- ↑ "HB 3077". Oregon State Legislature. 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ↑ "SB 624". Oregon State Legislature. 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- 1 2 "House Bill 3475". Oregon State Legislature. 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Legislative Status Report (see 7707, 2112)". Rhode Island Legislature. 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- 1 2 "Legislative status report". Rhode Island Legislature. 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Rhode Island House Defeats National Popular Vote Bill". ballot-access.org.

- 1 2 "Legislative status report (look for 5659, 164 in 2011)". Rhode Island Legislature. 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- 1 2 "Legislative Status Report (search for bills 5575, 346)". Rhode Island Legislature. 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- 1 2 "HB 1728". Tennessee General Assembly. 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "The Vermont Legislative Bill Tracking System (S.270)". Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- 1 2 "The Vermont Legislative Bill Tracking System (S.34)". Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Text of S31" (PDF). Vermont Legislature. 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- 1 2 "S31". Vermont Legislature. 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ↑ "Vermont Is Eighth State to Enact National Popular Vote Bill". BusinessWire. April 22, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- ↑ "HB1750, 2007–08". Washington State Legislature. 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "SB5628". Washington Legislature. 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- 1 2 "SB5599, 2009". Washington State Legislature. 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

External links

- Election Law Journal Symposium on National Popular Vote

- National Popular Vote

- Agreement Among the States to Elect the President by Nationwide Popular Vote – text of the interstate compact

- Every Vote Equal: A State-Based Plan for Electing the President by National Popular Vote – read or download book for free

- FairVote

- Common Cause

- Electoral College legislation at the National Conference of State Legislatures