XMPP

Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP) is a communications protocol for message-oriented middleware based on XML (Extensible Markup Language).[1] It enables the near-real-time exchange of structured yet extensible data between any two or more network entities.[2] Originally named Jabber,[3] the protocol was developed by the Jabber open-source community in 1999 for near real-time instant messaging (IM), presence information, and contact list maintenance. Designed to be extensible, the protocol has been used also for publish-subscribe systems, signalling for VoIP, video, file transfer, gaming, the Internet of Things (IoT) applications such as the smart grid, and social networking services.

Unlike most instant messaging protocols, XMPP is defined in an open standard and uses an open systems approach of development and application, by which anyone may implement an XMPP service and interoperate with other organizations' implementations. Because XMPP is an open protocol, implementations can be developed using any software license; although many server, client, and library implementations are distributed as free and open-source software, numerous freeware and commercial software implementations also exist.

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) formed an XMPP working group in 2002 to formalize the core protocols as an IETF instant messaging and presence technology. The XMPP Working group produced four specifications (RFC 3920, RFC 3921, RFC 3922, RFC 3923), which were approved as Proposed Standards in 2004. In 2011, RFC 3920 and RFC 3921 were superseded by RFC 6120 and RFC 6121 respectively, with RFC 6122 specifying the XMPP address format. In 2015, RFC 6122 was superseded by RFC 7622. In addition to these core protocols standardized at the IETF, the XMPP Standards Foundation (formerly the Jabber Software Foundation) is active in developing open XMPP extensions.

XMPP-based software is deployed widely across the Internet, and by 2003, was used by over ten million people worldwide, according to the XMPP Standards Foundation.[4]

| Internet protocol suite |

|---|

| Application layer |

| Transport layer |

| Internet layer |

| Link layer |

History

Jeremie Miller began working on the Jabber technology in 1998 and released the first version of the jabberd server on January 4, 1999.[5] The early Jabber community focused on open-source software, mainly the jabberd server, but its major outcome proved to be the development of the XMPP protocol.

The early Jabber protocol, as developed in 1999 and 2000, formed the basis for XMPP as published in RFC 3920 and RFC 3921 (the primary changes during formalization by the IETF's XMPP Working Group were the addition of TLS for channel encryption and SASL for authentication). Note that RFC 3920 and RFC 3921 have been superseded by RFC 6120 and RFC 6121, published in 2011.

The first IM service based on XMPP was Jabber.org, which has operated continuously and offered free accounts since 1999.[6] From 1999 until February 2006, the service used jabberd as its server software, at which time it migrated to ejabberd (both of which are free software application servers). In January 2010, the service migrated to the proprietary M-Link server software produced by Isode Ltd.[7]

In August 2005, Google introduced Google Talk, a combination VoIP and IM system that uses XMPP for instant messaging and as a base for a voice and file transfer signaling protocol called Jingle. The initial launch did not include server-to-server communications; Google enabled that feature on January 17, 2006.[8] Google has since added video functionality to Google Talk, also using the Jingle protocol for signaling. In May 2013, Google announced Jabber compatibility would be dropped from Google Talk for server-to-server federation, although it would retain client-to-server support.[9]

In January 2008, AOL introduced experimental XMPP support for its AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) service,[10] allowing AIM users to communicate using XMPP. However, in March 2008, this service was discontinued. As of May 2011, AOL offers limited XMPP support.[11]

In September 2008, Cisco Systems acquired Jabber, Inc., the creators of the commercial product Jabber XCP.[12]

In February 2010, the social-networking site Facebook opened up its chat feature to third-party applications via XMPP.[13] Some functionality was unavailable through XMPP, and support was dropped in April 2014.[14]

Similarly, in December 2011, Microsoft released an XMPP interface to its Microsoft Messenger service.[15] Skype, its de facto successor, also provides limited XMPP support.[16] However, these are not native XMPP implementations.

Strengths

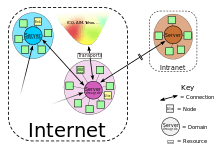

- Decentralization

- The architecture of the XMPP network is similar to email; anyone can run their own XMPP server and there is no central master server.

- Open standards

- The Internet Engineering Task Force formalized XMPP as an approved instant messaging and presence technology under the name of XMPP (the latest specifications are RFC 6120 and RFC 6121). No royalties or granted permissions are required to implement these specifications.

- History

- XMPP technologies have been in use since 1999. Many implementations of the XMPP standards exist for clients, servers, components, and code libraries.

- Security

- XMPP servers can be isolated (e.g., on a company intranet), and secure authentication (SASL) and encryption (TLS) have been built into the core XMPP specifications.

- Flexibility

- Custom functionality can be built on top of XMPP. To maintain interoperability, common extensions are managed by the XMPP Standards Foundation. XMPP applications beyond IM include chatrooms, network management, content syndication, collaboration tools, file sharing, gaming, remote systems control and monitoring, geolocation, middleware and cloud computing, VoIP, and identity services.

Weaknesses

- Does not support Quality of Service (QoS)

- Assured delivery of messages has to be built on-top of the XMPP layer. There are two XEPs proposed to deal with this issue, XEP-0184 Message delivery receipts which is a draft standard, and XEP-0333 Chat Markers which is considered experimental.

- Text-based communication

- Since XML is text based, normal XMPP has a higher network overhead compared to purely binary solutions. This issue is being addressed by the experimental XEP-0322: Efficient XML Interchange (EXI) Format, where XML is serialized in a very efficient binary manner, especially in schema-informed mode.

- In-band binary data transfer is limited

- Binary data must be first base64 encoded before it can be transmitted in-band. Therefore, any significant amount of binary data (e.g., file transfers) is best transmitted out-of-band, using in-band messages to coordinate. The best example of this is the Jingle XMPP Extension Protocol, XEP-0166.

- Does not support end-to-end encryption

- As of June 2015, XMPP lacks native end-to-end encryption support. XEP-0210 and associated XEPs proposed an implementation but were deferred. Off-the-Record Messaging (OTR) can be used atop XMPP for end-to-end encryption, although it only supports single-user text chat.

Decentralization and addressing

The XMPP network uses a client–server architecture; clients do not talk directly to one another. The model is decentralized - anyone can run a server. By design, there is no central authoritative server as there is with services such as AOL Instant Messenger or Windows Live Messenger. Some confusion often arises on this point as there is a public XMPP server being run at jabber.org, to which a large number of users subscribe. However, anyone may run their own XMPP server on their own domain.

Every user on the network has a unique XMPP address, called JID (for historical reasons, XMPP addresses are often called Jabber IDs). The JID is structured like an email address with a username and a domain name (or IP address[17]) for the server where that user resides, separated by an at sign (@), such as [email protected].

Since a user may wish to log in from multiple locations, they may specify a resource. A resource identifies a particular client belonging to the user (for example home, work, or mobile). This may be included in the JID by appending a slash followed by the name of the resource. For example, the full JID of a user's mobile account could be [email protected]/mobile.

Each resource may have specified a numerical value called priority. Messages simply sent to [email protected] will go to the client with highest priority, but those sent to [email protected]/mobile will go only to the mobile client. The highest priority is the one with largest numerical value.

JIDs without a username part are also valid, and may be used for system messages and control of special features on the server. A resource remains optional for these JIDs as well.

The means to route messages based on a logical endpoint identifier - the JID, instead of by an explicit IP Address present opportunities to use XMPP as an Overlay network implementation on top of different underlay networks.

XMPP as an extensible Message Oriented Middleware (xMOM) platform

XMPP provides a general framework for messaging across a network, which offers a multitude of applications beyond traditional Instant Messaging (IM) and the distribution of Presence data. While several service discovery protocols exist today (such as zeroconf or the Service Location Protocol), XMPP provides a solid base for the discovery of services residing locally or across a network, and the availability of these services (via presence information), as specified by XEP-0030 DISCO.[18]

Building on its capability to support discovery across local network domains, XMPP is well-suited for cloud computing where virtual machines, networks, and firewalls would otherwise present obstacles to alternative service discovery and presence-based solutions. Cloud computing and storage systems rely on various forms of communication over multiple levels, including not only messaging between systems to relay state but also the migration or distribution of larger objects, such as storage or virtual machines. Along with authentication and in-transit data protection, XMPP can be applied at a variety of levels and may prove ideal as an extensible middleware or Message Oriented Middleware (MOM) protocol. Widely known for its ability to exchange XML-based content natively, it has become an open platform for the exchange of other forms of content including proprietary binary streams, Full Motion Video (FMV) content, and the transport of file-based content, via for example the Jingle series of extensions. Here the majority of the applications have nothing to do with human communications (i.e., IM) but instead provide an open means to support machine-to-machine or peer-to peer communications across a diverse set of networks.

XMPP via HTTP and WebSocket transports

The original and "native" transport protocol for XMPP is Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), using open-ended XML streams over long-lived TCP connections.

As an alternative to the TCP transport, the XMPP community has also developed an HTTP transport for web clients as well as users behind restricted firewalls. In the original specification, XMPP could use HTTP in two ways: polling[19] and binding. The polling method, now deprecated, essentially implies messages stored on a server-side database are being fetched (and posted) regularly by an XMPP client by way of HTTP 'GET' and 'POST' requests. The binding method, implemented using Bidirectional-streams Over Synchronous HTTP (BOSH),[20] allows servers to push messages to clients as soon as they are sent. This push model of notification is more efficient than polling, where many of the polls return no new data.

Because the client uses HTTP, most firewalls allow clients to fetch and post messages without any hindrances. Thus, in scenarios where the TCP port used by XMPP is blocked, a server can listen on the normal HTTP port and the traffic should pass without problems. Various websites let people sign into XMPP via a browser. Furthermore, there are open public servers that listen on standard http (port 80) and https (port 443) ports, and hence allow connections from behind most firewalls. However, the IANA-registered port for BOSH is actually 5280, not 80.

A perhaps more efficient transport for real-time messaging is WebSocket, a web technology providing for bi-directional, full-duplex communications channels over a single TCP connection. XMPP over WebSocket binding is defined in the IETF proposed standard RFC 7395.

Implementations

XMPP is implemented by a large number of clients, servers, and code libraries.[21] These implementations are provided under a variety of software licenses.

Deployments

Several large public IM services natively use XMPP, including LiveJournal's "LJ Talk",[22] Nimbuzz, and HipChat. Various hosting services, such as DreamHost, enable hosting customers to choose XMPP services alongside more traditional web and email services. Specialized XMPP hosting services also exist in form of cloud so that domain owners need not directly run their own XMPP servers, including Cisco WebEx Connect, Chrome.pl, Flosoft.biz, i-pobox.net, and hosted.im.

Some of the largest messaging providers uses, or has been using, various forms of XMPP based protocols in their backend systems without necessarily exposing this fact to their end users. This includes WhatsApp, Gtalk and Facebook Chat[23][24] (the deprecated Facebook messaging system). Most of these deployments are built on the free-software, Erlang-based XMPP server called ejabberd.

XMPP is also used in deployments of non-IM services, including smart grid systems such as demand response applications, message-oriented middleware, and as a replacement for SMS to provide text messaging on many smartphone clients.

XMPP is the de facto standard for private chat in gaming related platforms such as Origin,[25] Raptr, PlayStation, and the now discontinued Xfire. The two notable exceptions being Steam[26] and Xbox LIVE that use their own proprietary messaging protocols.

Extensions

The XMPP Standards Foundation or XSF (formerly the Jabber Software Foundation) is active in developing open XMPP extensions. However, extensions can also be defined by any individual, software project, or organization. Another example is the federation protocol in Apache Wave, which is based on XMPP.[27]

Competing standards

XMPP has often been regarded as a competitor to SIMPLE, based on the Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) protocol, as the standard protocol for instant messaging and presence notification.[28][29]

The XMPP extension for multi-user chat[30] can be seen as a competitor to Internet Relay Chat (IRC), although IRC is far simpler, has far fewer features, and is far more widely used.

The XMPP extensions for publish-subscribe[31] provide many of the same features as the Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP).

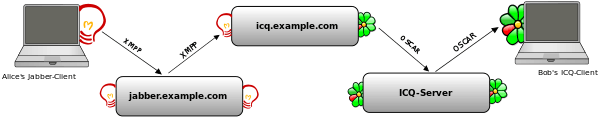

Connecting to other protocols

One of the original design goals of the early Jabber open-source community was enabling users to connect to multiple instant messaging systems (especially non-XMPP systems) through a single client application. This was done through entities called transports or gateways to other instant messaging protocols, but also to protocols such as SMS or email. Unlike multi-protocol clients, XMPP provides this access at the server level by communicating via special gateway services running alongside an XMPP server. Any user can "register" with one of these gateways by providing the information needed to log on to that network, and can then communicate with users of that network as though they were XMPP users. Thus, such gateways function as client proxies (the gateway authenticates on the user's behalf on the non-XMPP service). As a result, any client that fully supports XMPP can access any network with a gateway without extra code in the client, and without the need for the client to have direct access to the Internet. However, the client proxy model may violate terms of service on the protocol used (although such terms of service are not legally enforceable in several countries) and also requires the user to send their IM username and password to the third-party site that operates the transport (which may raise privacy and security concerns).

Another type of gateway is a server-to-server gateway, which enables a non-XMPP server deployment to connect to native XMPP servers using the built in interdomain federation features of XMPP. Such server-to-server gateways are offered by several enterprise IM software products, including:

- IBM Lotus Sametime[32][33]

- Skype for Business Server (formerly named Microsoft Lync Server and Microsoft Office Communications Server – OCS)[34]

Development

XSF

The XMPP Standards Foundation (XSF) develops and publishes extensions to XMPP through a standards process centered on XMPP Extension Protocols (XEPs, previously known as Jabber Enhancement Proposals - JEPs). The following extensions are in especially wide use:

- Data Forms[35]

- Service Discovery[36]

- Multi-User Chat[30]

- Publish-Subscribe [31] and Personal Eventing Protocol[37]

- XHTML-IM[38]

- File Transfer[39]

- Entity Capabilities[40]

- HTTP Binding[20]

- Jingle for voice and video

Internet of Things

XMPP features such as federation across domains, publish/subscribe, authentication and its security even for mobile endpoints are being used to implement the Internet of Things. Several XMPP extensions are part of the experimental implementation: Efficient XML Interchange (EXI) Format;[41] Sensor Data;[42] Provisioning;[43] Control;[44] Concentrators;[45] Discovery.[46]

These efforts are documented on a page in the XMPP wiki dedicated to Internet of Things[47] and the XMPP IoT mailing list.[48]

Specifications and standards

The IETF XMPP working group has produced a series of Request for Comments (RFC) documents:

- RFC 3920 (superseded by RFC 6120)

- RFC 3921 (superseded by RFC 6121)

- RFC 3922

- RFC 3923

- RFC 4622 (superseded by RFC 5122)

- RFC 4854

- RFC 4979

- RFC 6122 (superseded by RFC 7622)

The most important and most widely implemented of these specifications are:

- RFC 6120, Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP): Core, which describes client–server messaging using two open-ended XML streams. XML streams consist of <presence/>, <message/> and <iq/> (info/query). A connection is authenticated with Simple Authentication and Security Layer (SASL) and encrypted with Transport Layer Security (TLS).

- RFC 6121, Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP): Instant Messaging and Presence describes instant messaging (IM), the most common application of XMPP.

- RFC 7622, Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP): Address Format describes the rules for XMPP addresses, also called JabberIDs or JIDs. Currently JIDs use PRECIS (as defined in RFC 7564) for handling of Unicode characters outside the ASCII range.

See also

- Comparison of instant messaging clients

- Comparison of instant messaging protocols

- Comparison of XMPP server software

- Secure communication

- SIMPLE

References

- ↑ Johansson, Leif (April 18, 2005). "XMPP as MOM - Greater NOrdic MIddleware Symposium (GNOMIS)" (PDF). Oslo: University of Stockholm. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2011.

- ↑ Saint-Andre, P. (March 2011). Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP): Core. IETF. RFC 6120. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6120. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Jabber Inc". Cisco.com. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ "Jabber Instant Messaging User Base Surpasses ICQ" (Press release). XMPP Standards Foundation. September 22, 2003. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- ↑ "Open Real Time Messaging System". Tech.slashdot.org. 1999-01-04. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ Chatting Up the Chef Linux Journal March 1, 2003 by Marcel Gagné

- ↑ "Jabber.org – XMPP Server Migration". August 12, 2009. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ↑ Burd, Gary (January 17, 2006). "XMPP Federation". Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- ↑ "Google's chat client drops Jabber compatibility". Heise Online. May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ↑ Jensen, Florian (2008-01-17). "AOL adopting XMPP aka Jabber". Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ "AOL XMPP Gateway". 2011-05-14. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ "Cisco Announces Definitive Agreement to Acquire Jabber". Archived from the original on December 23, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ↑ "Facebook Chat Now Available Everywhere". Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Chat API (deprecated)". Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ Obasanjo, Dare (2011-12-14). "Anyone can build a Messenger client—with open standards access via XMPP". Windowsteamblog.com. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ Roettgers, Janko (2011-06-28). "Skype adds XMPP support, IM interoperability next? — Tech News and Analysis". Gigaom.com. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ RFC 6122

- ↑ https://xmpp.org/extensions/xep-0030.html

- ↑ Joe Hildebrand; Craig Kaes; David Waite (2009-06-03). "XEP-0025: Jabber HTTP Polling". Xmpp.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- 1 2 Ian Paterson; Dave Smith; Peter Saint-Andre; Jack Moffitt (2010-07-02). "XEP-0124: Bidirectional-streams Over Synchronous HTTP ([BOSH])". Xmpp.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ "Clients". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "Question FAQ #270-What is LJ Talk?". Livejournal.com. 2010-09-27. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ http://www.dylanleigh.net/notes/jabber-intro.html#Frequently_Asked_Questions

- ↑ https://blog.process-one.net/whatsapp-facebook-erlang-and-realtime-messaging-it-all-started-with-ejabberd/

- ↑ "Origin game platform sends login and messages in plain‐text". Slight Future. 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ↑ "libsteam.c". Github. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ↑ "Google Wave Federation Protocol". Google.

- ↑ "XMPP rises to face SIMPLE standard", Infoworld magazine, April 17, 2003 XMPP rises to face SIMPLE standard

- ↑ "XMPP vs SIMPLE: The race for messaging standards", Infoworld magazine, May 23, 2003 Infoworld.com

- 1 2 "XEP-0045: Multi-User Chat". xmpp.org.

- 1 2 "XEP-0060: Publish-Subscribe". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "Lotus Sametime 7.5 Interoperates with AIM, Google Talk", eWeek, December 6, 2006 Eweek.com

- ↑ "Lotus ships gateway to integrate IM with AOL, Yahoo, Google", Network World, December 6, 2006 Networkworld.com Archived November 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Unified Communications: Uniting Communication Across Different Networks", Microsoft Press Release, October 1, 2009 Microsoft.com Archived January 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "XEP-0004: Data Forms". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0030: Service Discovery". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0163: Personal Eventing Protocol". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0071: XHTML-IM". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0096: SI File Transfer". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0115: Entity Capabilities". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0322: Efficient XML Interchange (EXI) Format". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0323: Internet of Things - Sensor Data". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0324: Internet of Things - Provisioning". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0325: Internet of Things - Control". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0326: Internet of Things - Concentrators". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "XEP-0347: Internet of Things - Discovery". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "Tech pages/IoT systems". xmpp.org.

- ↑ "IOT Info Page". jabber.org.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol. |

- Official website

- xmpp-iot.org - the XMPP-IoT (Internet of Things) initiative

- Real-Time Communications Quick Start Guide

- Jabber User Guide

- "IETF Publishes XMPP RFCs: Core Jabber Protocols Recognized As Internet-Grade Technologies". Oct 4, 2004. Archived from the original on October 24, 2009.

- "Peter Saint-Andre on Jabber/XMPP", FLOSS Weekly, Twit TV, Dec 7, 2008, interviewed by Randal Schwartz and Leo Laporte