Word2vec

| Machine learning and data mining |

|---|

|

|

Machine learning venues

|

|

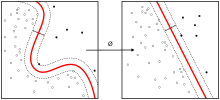

Word2vec is a group of related models that are used to produce word embeddings. These models are shallow, two-layer neural networks that are trained to reconstruct linguistic contexts of words. Word2vec takes as its input a large corpus of text and produces a vector space, typically of several hundred dimensions, with each unique word in the corpus being assigned a corresponding vector in the space. Word vectors are positioned in the vector space such that words that share common contexts in the corpus are located in close proximity to one another in the space.[1]

Word2vec was created by a team of researchers led by Tomas Mikolov at Google. The algorithm has been subsequently analysed and explained by other researchers.[2][3] Embedding vectors created using the Word2vec algorithm have many advantages compared to earlier algorithms like Latent Semantic Analysis.

Skip grams and CBOW

Word2vec can utilize either of two model architectures to produce a distributed representation of words: continuous bag-of-words (CBOW) or continuous skip-gram. In the continuous bag-of-words architecture, the model predicts the current word from a window of surrounding context words. The order of context words does not influence prediction (bag-of-words assumption). In the continuous skip-gram architecture, the model uses the current word to predict the surrounding window of context words. The skip-gram architecture weights nearby context words more heavily than more distant context words.[1][4] According to the authors' note,[5] CBOW is faster while skip-gram is slower but does a better job for infrequent words.

Parametrization

Results of word2vec training can be sensitive to parametrization. The followings are some important parameters in word2vec training.

Training algorithm

A Word2vec model can be trained with hierarchical softmax and/or negative sampling. To approximate the conditional log-likelihood a model seeks to maximize, the hierarchical softmax method uses a Huffman tree to reduce calculation. The negative sampling method, on the other hand, approaches the maximization problem by minimizing the log-likelihood of sampled negative instances. According to the authors, hierarchical softmax works better for infrequent words while negative sampling works better for frequent words and better with low dimensional vectors.[5] As training epochs increase, hierarchical softmax stops being useful.[6]

Sub-sampling

High frequency words often provide little information. Words with frequency above a certain threshold may be subsampled to increase training speed.

Dimensionality

Quality of word embedding increases with higher dimensionality. But after reaching some point, marginal gain will diminish.[1] Typically, the dimensionality of the vectors is set to be between 100 and 1,000.

Context window

Context window determines how many words before and after a given word would be included as context words of the given word. According to the authors' note, the recommended value is 10 for skip-gram and 5 for CBOW.[5]

Extensions

An extension of word2vec to construct embeddings from entire documents (rather than the individual words) has been proposed.[7] This extension is called paragraph2vec or doc2vec and has been implemented in the C, Python[8][9] and Java/Scala[10] tools (see below), with the Java and Python versions also supporting inference of document embeddings on new, unseen documents.

Word Vectors for Bioinformatics: BioVectors

An extension of word vectors for n-grams in biological sequences (e.g. DNA, RNA, and Proteins) for bioinformatics applications have been proposed by Asgari and Mofrad.[11] Named bio-vectors (BioVec) to refer to biological sequences in general with protein-vectors (ProtVec) for proteins (amino-acid sequences) and gene-vectors (GeneVec) for gene sequences, this representation can be widely used in applications of machine learning in proteomics and genomics. The results presented by[11] suggest that BioVectors can characterize biological sequences in terms of biochemical and biophysical interpretations of the underlying patterns.

Analysis

The reasons for successful word embedding learning in the word2vec framework are poorly understood. Goldberg and Levy point out that the word2vec objective function causes words that occur in similar contexts to have similar embeddings (as measured by cosine similarity) and note that this is in line with J. R. Firth's distributional hypothesis. However, they note that this explanation is "very hand-wavy" and argue that a more formal explanation would be preferable.[2]

Levy et al. (2015)[12] show that much of the superior performance of word2vec or similar embeddings in downstream tasks is not a result of the models per se, but of the choice of specific hyperparameters. Transferring these hyperparameters to more 'traditional' approaches yields similar performances in downstream tasks.

Preservation of semantic and syntactic relationships

The word embedding approach is able to capture multiple different degrees of similarity between words. Mikolov et al (2013)[13] found that semantic and syntactic patterns can be reproduced using vector arithmetic. Patterns such as “Man is to Woman as Brother is to Sister” can be generated through algebraic operations on the vector representations of these words such that the vector representation of “Brother” - ”Man” + ”Woman” produces a result which is closest to the vector representation of “Sister” in the model. Such relationships can be generated for a range of semantic relations (such as Country—Capital) as well as syntactic relations (e.g. present tense—past tense)

Assessing the quality of a model

Mikolov et al (2013)[1] develop an approach to assessing the quality of a word2vec model which draws on the semantic and syntactic patterns discussed above. They developed a set of 8869 semantic relations and 10675 syntactic relations which they use as a benchmark to test the accuracy of a model. When assessing the quality of a vector model, a user may draw on this accuracy test which is implemented in word2vec,[14] or develop their own test set which is meaningful to the corpora which make up the model. This approach offers a more challenging test than simply arguing that the words most similar to a given test word are intuitively plausible.[1]

Parameters and model quality

The use of different model parameters and different corpora sizes can greatly affect the quality of a word2vec model. Accuracy can be improved in a number of ways, including the choice of model architecture (CBOW or Skip-Gram), increasing the training data set, increasing the number of vector dimensions, and increasing the window size of words considered by the algorithm. Each of these improvements comes with the cost of increased computational complexity and therefore increased model generation time.[1]

In models using large corpora and a high number of dimensions, the skip-gram model yields the highest overall accuracy, and consistently produces the highest accuracy on semantic relationships, as well as yielding the highest syntactic accuracy in most cases. However, the CBOW is less computationally expensive and yields similar accuracy results.[1]

Accuracy increases overall as the number of words used increase, and as the number of dimensions increases. Mikolov et al[1] report that doubling the amount of training data results in an equivalent increase in computational complexity as doubling the number of vector dimensions.

Implementations

See also

- Autoencoder

- Document-term matrix

- Feature extraction

- Feature learning

- Language modeling § Neural net language models

- Vector space model

- Thought vector

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mikolov, Tomas; et al. "Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space". arXiv:1301.3781

.

. - 1 2 Goldberg, Yoav; Levy, Omer. "word2vec Explained: Deriving Mikolov et al.'s Negative-Sampling Word-Embedding Method". arXiv:1402.3722

.

. - ↑ Řehůřek, Radim. Word2vec and friends (Youtube video). Retrieved 2015-08-14.

- ↑ Mikolov, Tomas; Sutskever, Ilya; Chen, Kai; Corrado, Greg S.; Dean, Jeff (2013). Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. arXiv:1310.4546

.

. - 1 2 3 "Google Code Archive - Long-term storage for Google Code Project Hosting.". code.google.com. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ↑ "Parameter (hs & negative)". Google Groups. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ↑ Le, Quoc; et al. "Distributed Representations of Sentences and Documents.". arXiv:1405.4053

.

. - ↑ "Doc2Vec tutorial using Gensim". Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- ↑ "Doc2vec for IMDB sentiment analysis". Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Doc2Vec and Paragraph Vectors for Classification". Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- 1 2 Asgari, Ehsaneddin; Mofrad, Mohammad R.K. (2015). "Continuous Distributed Representation of Biological Sequences for Deep Proteomics and Genomics". PloS one. 10 (11): e0141287.

- ↑ Levy, Omer; Goldberg, Yoav; Dagan, Ido (2015). Improving Distributional Similarity with Lessons Learned from Word Embeddings. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

- ↑ Mikolov, Tomas; Yih, Wen-tau; Zweig, Geoffrey (2013). "Linguistic Regularities in Continuous Space Word Representations.". HLT-NAACL: pp. 746–751.

- ↑ "Gensim - Deep learning with word2vec". Retrieved 10 June 2016.