Spleen

| Spleen | |

|---|---|

Human spleen removed from a cadaver | |

Spleen | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Mesenchyme of dorsal mesogastrium |

| System | Immune system (lymphatic system and mononuclear phagocyte system) |

| Artery | Splenic artery |

| Vein | Splenic vein |

| Nerve | Splenic plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Lien |

| Greek | splḗn–σπλήν[1] |

| MeSH | A10.549.700 |

| TA | A13.2.01.001 |

| FMA | 7196 |

The spleen (from Greek σπλήν—splḗn[1]) is an organ found in virtually all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter.

The spleen plays important roles in regard to red blood cells (also referred to as erythrocytes) and the immune system.[2] It removes old red blood cells and holds a reserve of blood, which can be valuable in case of hemorrhagic shock, and also recycles iron. As a part of the mononuclear phagocyte system, it metabolizes hemoglobin removed from senescent erythrocytes. The globin portion of hemoglobin is degraded to its constitutive amino acids, and the heme portion is metabolized to bilirubin, which is removed in the liver.[3]

The spleen synthesizes antibodies in its white pulp and removes antibody-coated bacteria and antibody-coated blood cells by way of blood and lymph node circulation. A study published in 2009 using mice found that the red pulp of the spleen forms a reservoir that contains over half of the body's monocytes.[4] These monocytes, upon moving to injured tissue (such as the heart after myocardial infarction), turn into dendritic cells and macrophages while promoting tissue healing.[4][5][6] The spleen is a center of activity of the mononuclear phagocyte system and can be considered analogous to a large lymph node, as its absence causes a predisposition to certain infections.[7]

In humans, the spleen is brownish in color and is located in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen.[3][8]

Structure

The spleen, in healthy adult humans, is approximately 7 centimetres (2.8 in) to 14 centimetres (5.5 in) in length. It usually weighs between 150 grams (5.3 oz)[9] and 200 grams (7.1 oz).[10] An easy way to remember the anatomy of the spleen is the 1×3×5×7×9×11 rule. The spleen is 1" by 3" by 5", weighs approximately 7 oz, and lies between the 9th and 11th ribs on the left hand side.

Surfaces

The diaphragmatic surface of the spleen (or phrenic surface) is convex, smooth, and is directed upward, backward, and to the left, except at its upper end, where it is directed slightly to the middle. The spleen lies beneath the left diaphragm, beneath the ninth, tenth, and eleventh ribs. The diaphragm separates the spleen from the pleura and base of the left lung.

The visceral surface of the spleen is divided by a ridge into two regions: an anterior or gastric and a posterior or renal. The gastric surface is directed forward, upward, and toward the middle, is broad and concave, and is in contact with the posterior wall of the stomach. Below this it is in contact with the tail of the pancreas.

The renal (kidney) surface is directed medialward and downward. It is somewhat flattened, considerably narrower than the gastric surface, and is in relation with the upper part of the anterior surface of the left kidney and occasionally with the left adrenal gland.

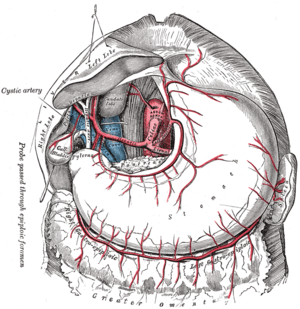

Blood supply

Near the middle of the spleen lies a long fissure, the splenic hilum. The hilum is the point of attachment for the gastrosplenic ligament, and the point of insertion for the splenic artery and splenic vein. There are other openings present for lymphatic vessels and nerves.

Like the thymus, the spleen possesses only efferent lymphatic vessels. The spleen is part of the lymphatic system. Both the short gastric arteries and the splenic artery supply it with blood.[11]

The germinal centers are supplied by arterioles called penicilliary radicles.[12]

Development

The spleen is unique in respect to its development within the gut. While most of the gut organs are endodermally derived (with the exception of the neural-crest derived adrenal gland), the spleen is derived from mesenchymal tissue.[13] Specifically, the spleen forms within, and from, the dorsal mesentery. However, it still shares the same blood supply—the celiac trunk—as the foregut organs.

Function

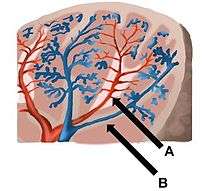

| Area | Function | Composition |

| red pulp | Mechanical filtration of red blood cells. In mice: Reserve of monocytes[4] |

|

| white pulp | Active immune response through humoral and cell-mediated pathways. | Composed of nodules, called Malpighian corpuscles. These are composed of:

|

Other functions of the spleen are less prominent, especially in the healthy adult:

- Production of opsonins, properdin, and tuftsin.

- Creation of red blood cells. While the bone marrow is the primary site of hematopoiesis in the adult, the spleen has important hematopoietic functions up until the fifth month of gestation. After birth, erythropoietic functions cease, except in some hematologic disorders. As a major lymphoid organ and a central player in the reticuloendothelial system, the spleen retains the ability to produce lymphocytes and, as such, remains a hematopoietic organ.

- Storage of red blood cells, lymphocytes and other formed elements. In horses, roughly 30% of the red blood cells are stored there. The red blood cells can be released when needed.[14] In humans, up to a cup (240 ml) of red blood cells can be held in the spleen and released in cases of hypovolemia.[15] It can store platelets in case of an emergency and also clears old platelets from the circulation. Up to a quarter of lymphocytes can be stored in the spleen at any one time.

Clinical significance

Enlarged spleen

Disorders include splenomegaly, where the spleen is enlarged for various reasons, such as cancer, specifically blood-based leukemias, and asplenia, where the spleen is not present or functions abnormally.

Traumas, such as a road traffic collision, can cause rupture of the spleen, which is a situation requiring immediate medical attention.

Spleen deflation

Human spleens have been noted to decrease in volume up to 40% when subjected to stimuli from strenuous exercise or hypoxic gas inhalation.[16]

Decreased function

Asplenia refers to a non-functioning spleen, which may be congenital, damaged by trauma, or caused by disease such as sickle cell anaemia. Hyposplenia refers to a partially functioning spleen. These conditions may cause:[5] a modest increase in circulating white blood cells and platelets; a diminished response to some vaccines, and an increased susceptibility to infection. In particular, there is an increased risk of sepsis from polysaccharide encapsulated bacteria. Encapsulated bacteria inhibit binding of complement or prevent complement assembled on the capsule from interacting with macrophage receptors. Phagocytosis needs natural antibodies, which are immunoglobulins that facilitate phagocytosis either directly or by complement deposition on the capsule. They are produced by IgM memory B cells (a subtype of B cells) in the marginal zone of the spleen.[17][18]

A splenectomy (removal of the spleen) also causes asplenia and results in a greatly diminished frequency of memory B cells.[19] A 28-year follow-up of 740 World War II veterans whose spleens were removed on the battlefield showed a significant increase in the usual death rate from pneumonia (6 rather than the expected 1.3) and an increase in the death rate from ischemic heart disease (41 rather than the expected 30), but not from other conditions.[20]

Accessory spleen

An accessory spleen is a small splenic nodule extra to the spleen usually formed in early embryogenesis. Accessory spleens are found in approximately 10 percent of the population[21] and are typically around 1 centimeter in diameter. Splenosis is a condition where displaced pieces of splenic tissue (often following trauma or splenectomy) autotransplant in the abdominal cavity as accessory spleens.[22]

Polysplenia is a congenital disease manifested by multiple small accessory spleens,[23] rather than a single, full-sized, normal spleen. Polysplenia sometimes occurs alone, but it is often accompanied by other developmental abnormalities such as intestinal malrotation or biliary atresia, or cardiac abnormalities, such as dextrocardia. These accessory spleens are non-functional.

Society and culture

The word spleen comes from the Ancient Greek σπλήν (splḗn), and is the idiomatic equivalent of the heart in English, i.e. to be good-spleened (εὔσπλαγχνος, eúsplankhnos) means to be good-hearted or compassionate.[24]

In English the word spleen was customary during the period of the 18th century. Authors like Richard Blackmore or George Cheyne employed it to characterise the hypochondriacal and hysterical affections.[25][26] William Shakespeare, in Julius Caesar uses the spleen to describe Cassius' irritable nature.

Must I observe you? must I stand and crouch

Under your testy humour? By the gods

You shall digest the venom of your spleen,

Though it do split you; for, from this day forth,

I'll use you for my mirth, yea, for my laughter,

When you are waspish.[1]

- ^ Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare Act 4:1

In French, "splénétique" refers to a state of pensive sadness or melancholy. It has been popularized by the poet Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) but was already used before in particular to the Romantic literature (19th century). The word for the organ is "rate".

The connection between spleen (the organ) and melancholy (the temperament) comes from the humoral medicine of the ancient Greeks. One of the humours (body fluid) was the black bile, secreted by the spleen organ and associated with melancholy. In contrast, the Talmud (tractate Berachoth 61b) refers to the spleen as the organ of laughter while possibly suggesting a link with the humoral view of the organ. In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England, women in bad humor were said to be afflicted by the spleen, or the vapours of the spleen. In modern English, "to vent one's spleen" means to vent one's anger, e.g. by shouting, and can be applied to both males and females. Similarly, the English term "splenetic" is used to describe a person in a foul mood.

Other animals

In cartilaginous and ray-finned fish, it consists primarily of red pulp and is normally somewhat elongated, as it lies inside the serosal lining of the intestine. In many amphibians, especially frogs, it has the more rounded form and there is often a greater quantity of white pulp.[27]

In reptiles, birds, and mammals, white pulp is always relatively plentiful, and in birds and mammals the spleen is typically rounded, but it adjusts its shape somewhat to the arrangement of the surrounding organs. In most vertebrates, the spleen continues to produce red blood cells throughout life; only in mammals this function is lost in adults. Many mammals have tiny spleen-like structures known as haemal nodes throughout the body that are presumed to have the same function as the spleen.[27] The spleens of aquatic mammals differ in some ways from those of fully land-dwelling mammals; in general they are bluish in colour. In cetaceans and manatees they tend to be quite small, but in deep diving pinnipeds, they can be quite massive, due to their function of storing red blood cells.

The only vertebrates lacking a spleen are the lampreys and hagfishes (the Cyclostomata). Even in these animals, there is a diffuse layer of haematopoeitic tissue within the gut wall, which has a similar structure to red pulp and is presumed to be homologous with the spleen of higher vertebrates.[27]

In mice, the spleen stores half the body's monocytes so that upon injury, they can migrate to the injured tissue and transform into dendritic cells and macrophages and so assist wound healing.[4]

Gallery

The celiac artery and its branch.

The celiac artery and its branch. Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the upper part of the abdomen.

Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the upper part of the abdomen. Transverse section of the spleen, showing the trabecular tissue and the splenic vein and its tributaries.

Transverse section of the spleen, showing the trabecular tissue and the splenic vein and its tributaries. Back of lumbar region, showing surface markings for kidneys, ureters, and spleen.

Back of lumbar region, showing surface markings for kidneys, ureters, and spleen. Side of thorax, showing surface markings for bones, lungs (purple), pleura (blue), and spleen (green).

Side of thorax, showing surface markings for bones, lungs (purple), pleura (blue), and spleen (green).- Spleen

See also

References

- 1 2 σπλήν, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ Spleen, Internet Encyclopedia of Science

- 1 2 Mebius, RE; Kraal, G (2005). "Structure and function of the spleen". Nature reviews. Immunology. 5 (8): 606–16. doi:10.1038/nri1669. PMID 16056254.

- 1 2 3 4 Swirski, FK; Nahrendorf, M; Etzrodt, M; Wildgruber, M; Cortez-Retamozo, V; Panizzi, P; Figueiredo, JL; Kohler, RH; Chudnovskiy, A; Waterman, P; Aikawa, E; Mempel, TR; Libby, P; Weissleder, R; Pittet, MJ (2009). "Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites". Science. 325 (5940): 612–6. doi:10.1126/science.1175202. PMC 2803111

. PMID 19644120.

. PMID 19644120. - 1 2 Jia, T; Pamer, EG (2009). "Immunology. Dispensable but not irrelevant". Science. 325 (5940): 549–50. doi:10.1126/science.1178329. PMC 2917045

. PMID 19644100.

. PMID 19644100. - ↑ Finally, the Spleen Gets Some Respect By NATALIE ANGIER, The New York Times, August 3, 2009

- ↑ Brender, Erin (2005-11-23). Richard M. Glass, ed. Illustrated by Allison Burke. "Spleen Patient Page" (PDF). Journal of the American Medical Association. American Medical Association. 294 (20): 2660. doi:10.1001/jama.294.20.2660. PMID 16304080. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ Loscalzo, Joseph; Fauci, Anthony S.; Braunwald, Eugene; Dennis L. Kasper; Hauser, Stephen L; Longo, Dan L. (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine. McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-146633-2.

- ↑ eMedicine > Splenomegaly Author: David J Draper. Coauthor(s): Ronald A Sacher, Emmanuel N Dessypris, Lewis J Kaplan. Updated: Oct 4, 2009

- ↑ Spielmann, Audrey L.; David M. DeLong; Mark A. Kliewer (1 January 2005). "Sonographic Evaluation of Spleen Size in Tall Healthy Athletes". American Journal of Roentgenology. American Roentgen Ray Society. 2005 (184): 45–49. doi:10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840045. PMID 15615949. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ↑ Blackbourne, Lorne H (2008-04-01). Surgical recall. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-7817-7076-7.

- ↑ "Penicilliary radicles". Medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ Vellguth, Swantje; Brita von Gaudecker; Hans-Konrad Müller-Hermelink (1985). "The development of the human spleen". Cell and Tissue Research. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. 242 (3): 579–592. doi:10.1007/BF00225424. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ↑ Carey, Bjorn (May 5, 2006). "Horse science: What makes a Derby winner - Spleen acts as a 'natural blood doper,' scientist says". MSNBC.com. Retrieved 2006-05-09.

- ↑ "Spleen: Information, Surgery and Functions". Childrens Hospital of Pittsburgh - Chp.edu. 2010-11-17. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=WOS&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=6&SID=2Ar3fUWCRYhRDCYsryW&page=1&doc=3(subscriptionrequired)

- ↑ Di Sabatino, A; Carsetti, R; Corazza, GR (Jul 2, 2011). "Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states". Lancet. 378 (9785): 86–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61493-6. PMID 21474172.

- ↑ Carsetti, R; Rosado, MM; Wardmann, H (February 2004). "Peripheral development of B cells in mouse and man". Immunological reviews. 197: 179–91. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0109.x. PMID 14962195.

- ↑ Kruetzmann, S; Rosado, MM; Weber, H; Germing, U; Tournilhac, O; Peter, HH; Berner, R; Peters, A; Boehm, T; Plebani, A; Quinti, I; Carsetti, R (Apr 7, 2003). "Human immunoglobulin M memory B cells controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are generated in the spleen". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (7): 939–45. doi:10.1084/jem.20022020. PMC 2193885

. PMID 12682112.

. PMID 12682112. - ↑ Dennis Robinette, C.; Fraumeni, Josephf. (1977). "Splenectomy and Subsequent Mortality in Veterans of the 1939-45 War". The Lancet. 310 (8029): 127–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(77)90132-5. PMID 69206.

- ↑ Moore, Keith L. (1992). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. p. 187. ISBN 0-683-06133-X.

- ↑ Abu Hilal M; Harb A; Zeidan B; Steadman B; Primrose JN; Pearce NW (January 5, 2009). "Hepatic splenosis mimicking HCC in a patient with hepatitis C liver cirrhosis and mildly raised alpha feto protein; the important role of explorative laparoscopy". World Journal of Surgical Oncology. England: BioMed Central. 7 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-7-1. PMC 2630926

. PMID 19123935.

. PMID 19123935. - ↑ "polysplenia" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Robertson's Word Pictures of the New Testament, commentary on 1 Peter 3:8

- ↑ Cheyne, George: The English Malady; or, A Treatise of Nervous Diseases of All Kinds, as Spleen, Vapours, Lowness of Spirits, Hypochondriacal and Hysterical Distempers with the Author's own Case at large, Dublin, 1733. Facsimile ed., ed. Eric T. Carlson, M.D., 1976, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, ISBN 978-0-8201-1281-7;

- ↑ Blackmore, Richard: Treatise of the spleen and vapors. London, 1725

- 1 2 3 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 410–411. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

| Look up spleen in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spleen. |

- Anatomy figure: 38:03-01 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"The visceral surface of the spleen."

- Anatomy image:7881 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- "spleen" from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- Spleen and Lymphatic System, Kidshealth.org (American Academy of Family Physicians)

- Spleen Diseases from MedlinePlus

- "Finally, the Spleen Gets Some Respect" New York Times piece on the spleen

- Normal range of spleen size for a given age in children