V–IV–I turnaround

In music, the V–IV–I turnaround, or blues turnaround,[3] is one of several cadential patterns traditionally found in the twelve-bar blues, and commonly found in rock and roll.[4]

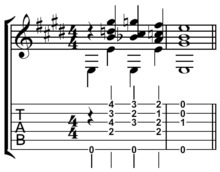

The cadence moves from the tonic to dominant, to subdominant, and back to the tonic. "In a blues in A, the turnaround will consist of the chords E7, D7, A7, E7 [V–IV–I–V[5]]."[6] V may be used in the last measure rather than I since, "nearly all blues tunes have more than one chorus (occurrence of the 12-bar progression), the turnaround (last four bars) usually ends on V, which makes us feel like we need to hear I again, thus bringing us around to the top (beginning) of the form again.".[5]

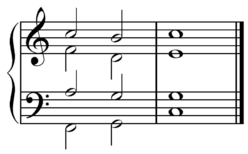

The blues turnaround may be "dress[ed] up" by using Vaug ![]() Play ("an uptown V7") instead of V7

Play ("an uptown V7") instead of V7 ![]() Play , "adding a touch of jazzy sophistication."[7] An important variation is the jazz influenced turnaround ii-V-I-V.[5]

Play , "adding a touch of jazzy sophistication."[7] An important variation is the jazz influenced turnaround ii-V-I-V.[5]

History

"It seems likely that the blues turnaround evolved from ragtime-type music", the earliest example being I–I7–IV–iv–I (in C: C–C7–F–Fm–C), "The Japanese Grand March".[8] This is a plagal cadence featuring a dominant seventh tonic (I or V/IV) chord. However, Baker cites a turnaround containing "How Dry I Am" as the "absolutely most commonly used blues turnaround".[8] Fischer describes the turnaround as the last two measures of the blues form, or I7 and V7, with variations including I7–IV7–I7–V7-[9]

Analysis

The root movement of the V−IV−I cadential formula found in the blues is considered nontraditional from the standpoint of Western harmony.[10] The motion of the V−IV−I cadence has been considered "backward,"[4] as, in traditional harmony, the subdominant normally prepares for the dominant which then has a strong tendency to resolve to the tonic. However, an alternative analysis has been proposed in which the IV acts to intensify the seventh of V, which is then resolved to the third of the tonic.[4]

The V–IV–I movement has also been characterized as "unwinding" the V-I cadence with the addition of the passing IV.[11]

See also

Sources

- ↑ Brozman, Bob (1996). Bob Brozman's Bottleneck Blues Guitar, p.7. ISBN 1-57623-727-3.

- ↑ Manus, Ron (2003). Jazz Lead Guitar Solos: The Ultimate Guide to Playing Great Leads, Book & CD, p.16. ISBN 0739031589.

- ↑ Gress, Jesse (2006). Guitar Licks of the Texas Blues-Rock Heroes, p.16. ISBN 0-87930-876-1.

- 1 2 3 Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as musicians: Revolver through the Anthology. Oxford University Press. p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Alfred Publishing (2003). Electric Bass for Guitarists, p. 34. ISBN 0-7390-3335-2.

- ↑ Tony Skinner, Andy Drudy (2006). Guitar Lessons Blues and Rock: 10 Easy-to-follow Guitar Lessons, p.18. ISBN 1-898466-76-9.

- ↑ Johnston, Richard (2007). How to Play Blues Guitar: The Basics and Beyond, p. 19. ISBN 0-87930-910-5.

- 1 2 Baker, Duck (2004). Duck Baker's Fingerstyle Blues Guitar 101, p.17. ISBN 0-7866-7210-2.

- ↑ Fischer, Peter (2000). Blues Guitar Rules, p.31. ISBN 3-927190-64-0.

- ↑ Stephenson, Ken (2002). "Analyzing a Hit". What To Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis. Yale University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-300-09239-3.

- ↑ Pedlar, Dominic (2003). The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles, p.30. ISBN 0-7119-8167-1 and .