Tumblehome

In naval architecture, the tumblehome is the narrowing of a ship's hull with greater distance above the water-line. Expressed more technically, it is present when the beam at the uppermost deck is less than the maximum beam of the vessel.

A small amount of tumblehome is normal in many designs in order to allow any small projections at deck level to clear wharves.[1]

Origins

Tumblehome was common on wooden warships for centuries. In the era of oared combat ships it was quite common, placing the oar ports as far abeam as possible. This also made it more difficult to board by force, as the ships would come to contact at their widest points, with the decks some distance apart. The narrowing of the hull above this point made the boat more stable by lowering the weight above the waterline, which is one of the reasons it remained common during the age of cannon-armed ships. In addition, the sloping sides of a ship with an extreme tumblehome (45 degrees or more) increased the effective thickness of the hull versus flat horizontal trajectory gunfire (a straight line through faced more material to penetrate) and increased the likelihood of a shell striking the hull being deflected—much the same reasons that later tank armor was sloped.

It can be seen as well in steel constructed warships of the early 1880s when the United States and most European navies began building steel warships. France was predominantly strong in promoting the tumblehome design in their warships, advocating tumblehome to reduce the weight of the upper deck, as well as making the vessel more seaworthy and creating greater freeboard.[2] France sold their newly constructed pre-dreadnought battleship Tsesarevich to the Russian Imperial Navy in time for it to fight as Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft's flagship at the Battle of the Yellow Sea on 10 August 1904. The Russo-Japanese War proved that the tumblehome battleship design was excellent for long distance navigation, especially when encountering narrow canals, and other waterways; but that it could be dangerously unstable when watertight integrity was breached.[3] Four tumblehome Borodino-class battleships, which had been built in Russian yards to Tsesarevich's basic design, fought on 27 May 1905 at Tsushima. The fact that three of the four were lost in this battle resulted in the discontinuing of the tumblehome design in future warships for nearly all navies.

A degree of tumblehome also facilitates paddling in a canoe or kayak,[4] while a greater degree of flare (its opposite) accommodates more cargo.[5]

Modern warship design

Tumblehome has been used in proposals for several modern ship projects. The hullform in combination with choice of materials and so forth results in decreased radar reflection, which together with other signature (sound, heat etc.) dampening measures makes stealth ships. This faceted appearance is common application of the principles of stealth aircraft. The US Navy's Zumwalt-class destroyers are a modern example.

Due to stability concerns, most warships with wave-piercing hulls combine tumblehome with multi-hull designs, such as the Type 022 missile boat.

In narrowboat design

The inward slope of a narrowboat's superstructure (from gunwales to roof) is referred to as tumblehome. The amount of tumblehome is one of the key design choices when specifying a narrowboat, because the widest part of a narrowboat is rarely more than 7 feet across, so even a modest change to the slope of the cabin sides makes a significant difference to the "full-height" width of the cabin interior. Too great a tumblehome would make a boat difficult to pass through for a tall person; too little and the cabin roof edges are at risk of damage when the boat is passing through a tunnel (many canal tunnels on the British inland waterways have subsided, bringing the curve of the roof closer to the water level).

In automobile design

The inward slope of the "greenhouse" above the beltline is also called the tumblehome. An example of a car with a pronounced tumblehome is the Lamborghini Countach. Less commonly, the inward curve of the body near the bottom may also be called a tumblehome. In 21st century automobile designs this turnunder is less pronounced or eliminated to reduce aerodynamic drag and to help keep the lower portions of the vehicle cleaner under wet conditions.

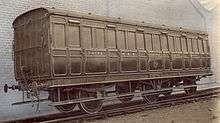

In railway design

The inwardly curving portions of railway passenger carriages at the point where the carriage sides join the underframes is also called the tumblehome. Tumblehome styling of railway carriages was particularly prevalent in Britain and Ireland (or on railways influenced by British engineers or equipment builders) in the 19th century and "wood body" era of the early 20th century. This enabled the wooden step running the length of the carriage to remain within the dimensions of the loading gauge, while allowing maximum width for the main body of the carriage. Thus there was space to place a foot when entering or leaving the carriage.

A tumblehome remains a feature of railway carriages in Great Britain and can be seen in most modern designs of passenger rolling stock.

Some recent vehicle designs for continental Europe, such as the "Lint" and "Talent" vehicles, also feature a tumblehome profile, which in some vehicles leads to the need for a retractable step to bridge the gap between vehicle floor and station platforms. The operation time of these steps, which must be fully extended before the sliding doors may be opened, can be observed to increase the train waiting time ("dwell time") at stations, compared to vehicles without such steps.

References

Footnotes

Works cited

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–05. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Mather, Frederic G. (1885). The Evolution of Canoeing

- Pursey, H. J. (1959). Merchant Ship Construction Especially Written for the Merchant Navy

- Vaillancourt, Henri. Traditional Birchbark Canoes Built in the Malecite, Penobscot and Passamaquoddy style

- DDG-1000 Zumwalt / DD(X) Multi-Mission Surface Combatant Future Surface Combatant. GlobalSecurity.org. Modern use of tumblehome.