Tobermore

| Tobermore | |

| Irish: An Tobar Mór | |

The village centre |

|

Tobermore |

|

| Population | 578 (2001 Census) |

|---|---|

| Irish grid reference | H8396 |

| – Belfast | 34 mi (55 km) |

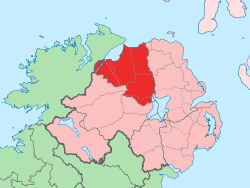

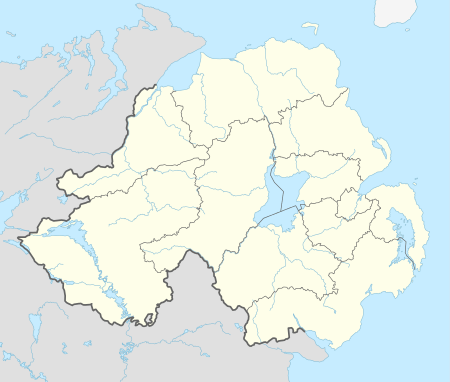

| District | Mid-Ulster |

| County | County Londonderry |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MAGHERAFELT |

| Postcode district | BT45 |

| Dialling code | 028 |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

| EU Parliament | Northern Ireland |

| UK Parliament | Mid Ulster |

| NI Assembly | Mid Ulster |

|

|

Coordinates: 54°48′40″N 6°42′25″W / 54.811°N 6.707°W

Tobermore (locally [ˌtʌbərˈmoːr], named after the townland of Tobermore[1]) is a small village in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It lies 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south-south-west of Maghera and 5.5 miles (8.9 km) north-west of Magherafelt. Tobermore lies within the civil parish of Kilcronaghan and is part of Mid-Ulster District. It was also part of the former barony of Loughinsholin.

Tobermore has won the Best Kept Small Village award four times and the Best Kept Large Village award in 1986.[2] Most recently in September 2011, Tobermore won the Translink Ulster In Bloom village category for the third year in a row.[3][4][5]

Etymology

Tobermore is named after the townland of Tobermore which is an anglicisation of the Irish words tobar meaning "well" and mór meaning "big/great", thus Tobermore means "big/great well".[6][7] During the seventeenth century, Tobermore was also known as Tobarmore and Tubbermore, with Tubbermore being the preferred usage of the Masonic Order even to this day.[8]

Topography

Tobermore lies on the descending slope of Slieve Gallion. Prominent hills are: Calmore Hill (in Calmore), 268 feet (82 m); and Fortwilliam (in Tobermore), 200 feet (61 m) high.[9]

A large oak tree called the Royal Oak grew near Calmore Castle in Tobermore.[9] Until it was destroyed in a heavy storm, the Royal Oak was said to have been so large that horsemen on horseback could not touch one another with their whips across it. From this vague description, it is conjectured that the Royal Oak was about 10 feet (3.0 m) in diameter or 30 feet (9.1 m) in circumference.[9] Another oak tree that once grew near Tobermore was so tall and straight that it was known as the Fishing Rod.[9] Tradition is that all of the townlands were once covered with magnificent oak trees.[9]

The Moyola River runs from west to east half a mile to the north of Tobermore village, heading through the townlands of Ballynahone Beg and Ballynahone More. In these two townlands lies Ballynahone Bog, one of the largest lowland raised bogs in Northern Ireland.[10]

Townlands

Origins of Tobermore village

The earliest reference to the actual settlement of Tobermore is in the mid-18th century of a house built in 1727 that belonged to a James Moore. At some point in the 18th century, the fair that was held at the Gort of the parish church was relocated to Tobermore, which is described as consisting of only Moore's house and a few mud huts. The development and growth of the village can be traced back to this period.[11]

Pre-modern history

Fortwilliam Hill

Fortwilliam Hill is situated between the Fortwilliam, Lisnamuck, and Maghera roads in Tobermore, overlooking the River Moyola. Upon it lies Fortwilliam rath, which was built c700-1000AD,[12] and Fortwilliam House, a listed building, built in 1795 by John Stevenson Esq of "The Stevensons the Linen People".[13] The rath was historically known under variations of Donnagrenan, which is most likely derived from the Irish Dún na Grianán, meaning "fort of the eminent place".[11] It's modern name like that of the adjacent house where bestowed upon them by Mr. Jackson, who named it after Fort William, Scotland, which was named in honour of King William III in 1690.[9][11] A contradictory reason mentioned by John O'Donovan is that the O'Hagans of Ballynascreen claimed it was built and named for Sir William O'Hagan, however O'Donovan discounts their claims due to other claims they make that are contrary to reality.[14]

Fortwilliam rath is presently described as a well-preserved semi-defensive high status monument, built to withstand passing raids, being relatively large at 30 meters in diameter. It is also declared a monument of regional importance giving it statutory protective status.[12] Fortwilliam House was described by John MacCloskey in 1821 as having a commanding position and being amongst the most pleasing of buildings and the most prominent in the district.[13][15]

Kilcronaghan parish church

Presbyterian congregation

The first Presbyterian congregation that serviced Tobermore and the general Loughinsholin barony area was founded in Knockloughrim in 1696.[16]

In 1736, an application was made to the Presbyterian Synod of Ulster to create a congregation in Tobermore. This initial request was denied as it would have depleted the congregation in neighbouring Maghera. In 1737 a renewed application was made with "such a strong case" put forward it was accepted by the Synod. It was requested that some of the people who would fall under the new congregation be at least eight miles from Maghera.[17]

The boundaries between the congregations of Maghera and Tobermore were to be the Moyola River, from Newforge Bridge to Corrin Bridge.[17][18] In 1743 however, nineteen families from Ballynahone, which straddles the Moyola River, were transferred from Maghera into the Tobermore congregation.[17] The fourth minister of the Tobermore congregation, the Reverend William Brown, saw the need for the formation of a new congregation in Draperstown and facilitated its development in 1835 despite meaning losing around 70 families from his Tobermore congregation.[18]

Volunteers and yeomanry

In November 1780, a meeting was convened of the Tobermore Volunteer company, commanded by John Stevenson, at which the Reverend James Whiteside preached.[19]

At several points during the 19th century, the British parliament commissioned reports listing the Yeomanry officers of Ireland. For Tobermore the following are listed:

- 1804 report - Kilcronaghan division of the Loughinsholin Battalion: Captain James Stephenson, commissioned 5 November 1803; Lieutenant Robert Bryan, commissioned 13 March 1804; and Samuel M'Gown (McGowan), also commissioned on 13 March 1804.[20]

- 1825 report - Tobermore corps: Captain James Stevenson, commissioned 18 November 1808. No lieutenants are listed.[21]

- 1834 report - "Tobbermore" corps: Captain James Stevenson, commissioned 18 November 1808; Lieutenant John Stevenson, commissioned 5 March 1831; and Lieutenant H. Stevenson.[22]

Non-payment of rents

During the early nineteenth century, the inhabitants of Tobermore are recorded as having displayed a very unruly disposition towards the payment of their rents towards their landlord Mr. Miller of Moneymore. It is stated that the inhabitants resisted the "pounding of their cattle, executed by him, with pitchforks and sundry other primitive implements of warfare". When they found that resistance was useless they employed Mr. Costello, one of the orators of the Corn Exchange to litigate their cause at the Magherafelt sessions, but here they were also unsuccessful.[23]

A chancery lawsuit going on between Ball and Co. of Dublin and Sir George Hill operated as an obstruction to the improvement of the village as it stood upon the estate disputed with non payment of rents. The main reason for the non payment was that the tenants didn't believe they had sufficient security in their rent receipts to prevent repetition for the same year's rent. During the same period it is noted that there were no illicit distillation of alcohol and no outrages for many years in the village except for a few assaults in the street on those who came to collect the rent. After the repayment of rents resumed it was remarked that "they were so long free of rent, none of them became in the end, the least degree richer", this may have been because as it was also remarked "their rent money which if saved every year would have secured some of them a comfortable competence found its way to the whiskey shops of the village and neighbourhood".[23]

Orange and Temperance Hall

Tobermore Orange and Temperance Hall was built in 1888 by Andrew Johnston of Aghagaskin, Magherafelt.[24] It is used for band practices and also by several organisations: Orange Order lodges 131 and 684; Royal Black Preceptory lodge 390; the Tobermore Walker Club of the Apprentice Boys of Derry; and Tobermore Masonic Lodge.[24]

Modern history

Home Rule

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The major issue in Ireland at the end of the nineteenth century and the start of the twentieth century was Irish Home Rule. In 1893 Viscount Templeton formed the first Unionist Clubs to coordinate opposition against Home Rule.[25][26] Hiram Parkes Wilkinson the son of Sir Hiram Shaw Wilkinson would found the Tobermore Unionist Club.[27]

The Rev. J. Walker Brown in 1912 released an anti-Home Rule pamphlet titled The Siege of Tobermore, where he details how best to defend Tobermore should "the enemy" march upon the village in a manner similar to that of the Siege of Derry.[28]

Tobermore also receives a mention in the third verse of the anti-Home Rule ballad titled The Union Cruiser.[29][30]

World War I

During World War I, 121 inhabitants of Tobermore, out of a population of around 350, enlisted with the Ulster Division, with the Mid Ulster Mail reporting that "This loyal little village has a war record that is perhaps unique".[31] Of those who enlisted, 24 were killed and 33 were wounded.[32]

The names of those who volunteered are preserved on a Roll of Honour painted by local man, Samuel Nelson, and was unveiled by Denis Henry, MP for South Londonderry. This Roll of Honour resides in Tobermore Orange & Temperance Hall.[31]

In Tobermore's Presbyterian graveyard lies the headstone of Bobbie Wisner, who died of natural causes at home in 1915. As he had trained and drilled with his adult comrades in the 36th Ulster Division, and was held in such high esteem, he was buried with full military honours.[18]

Victory Day

In 1946, Tobermore held a World War II Victory Fete. The Constitution newspaper states: "It was the first venture of its kind held in South Derry, and it was also among the very first organised 'Victory Day' celebrations to take place in the Province. Not only that, but Tobermore's 'Victory Salute' to that great achievement which crowned the Allied arms so magnificently little over a year ago, was availed of to give practical expression to the pride which the people of South Derry generally take..."[31] The Constitution also states: "In the preparatory arrangements nothing was left undone to ensure that it would prove a resounding success and certainly Tobermore's Victory Fete will long be regarded as one of the most memorable ventures in the district."[31]

The Victory Fete was attended by Sir Ronald Ross, MP for the City and County of Londonderry, the band of the 1st Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles and the local units of the Maghera and Tobermore Army Cadet Force.[31]

The Troubles

Prior to the modern Troubles, during the period of the Belfast Troubles (1920–1922), there was an attempt on Wednesday, 2 April 1921, to blow up the bridge over the Moyola River outside Tobermore.[33]

During the modern Troubles, Tobermore came under an area known by some as the Murder triangle. All of the people killed in the Tobermore area were Protestant:[34]

- Samuel Porter (30), killed 22 November 1972 by the IRA, Nelson was a member of the Ulster Defence Regiment, and was shot dead outside his home in Ballynahone while off-duty.[34]

- Noel Davis (22), killed 24 May 1975 by the INLA. Davis was a member of the Royal Ulster Constabulary. He was murdered by a booby trapped bomb in an abandoned car in Ballynahone, outside Tobermore.[34]

- Alexander Watters (62), killed 16 March 1977 - A civilian, Watters was shot dead whilst cycling along the road between Tobermore and Draperstown. It is not known what group killed him or for what reason.[34]

On 7 September 1968, divisions of the Ulster Protestant Volunteers, paraded through Tobermore.[35] It consisted of eight bands and around 450 people, most of whom wore Ulster Constitution Defence Committee sashes.[35] Ian Paisley and Free Presbyterian ministers featured prominently in the parade.[35]

In October 1972, an Ulster Vanguard political rally was held in Tobermore, where Ulster Unionist Party deputy leader, John Taylor, made a speech on the use of violence stating: "We should make it clear that force means death and fighting, and whoever gets in our way, whether republicans or those sent by the British government, there would be killings".[36]

There were four bomb hoaxes in Tobermore during 2010 the most recent on 29 July 2010 and 19 August 2010, both found in the centre of the village causing a lot of traffic disruption and resulting in people being evacuated from their homes.[37][38]

Recent history

On 29 July 2006, Ronald Mackie, a visitor from Scotland, who was over to attend a loyalist band parade in nearby Maghera, was kicked and beaten before being run over and killed after a row flared during a disco held at Tobermore United Football Club. Four men were charged and two; John Richard Stewart, from Maghera, and Paul Johnston, from Castledawson, were later convicted of manslaughter.[39][40]

On 16 August 2008, over twelve hours of torrential rain caused the Moyola River to burst its banks and saw the flooding of the main Tobermore-Maghera road, the neighbouring football club buildings and pitch of Tobermore United F.C. and Tobermore Golf Driving Range.[41][42]

Notable people

Dr. Adam Clarke (1762–1832) – British Methodist theologian and celebrated Biblical scholar born in the townland of Moybeg north of Tobermore village.[8]

Alexander Carson (1776–1844) – Prominent Irish Baptist, pastor of Tobermore Baptist Church and author of the classic Baptism, Its Mode and Subjects. In dedication to Alexander Carson, his church in Tobermore, founded in 1814, was named the Carson Memorial, and a housing estate opposite it named Carson Court.

Harry Gregg MBE (born 25 October 1932) – Former Manchester United and Northern Ireland goalkeeper. Harry Gregg was born in Tobermore though grew up in Coleraine.

Captain James McDowell (1742–1815) – USA revolutionary war captain, born in the townland of Clooney, outside Tobermore. Aged 16 he emigrated to the USA in 1758 settling in Chester County, Philadelphia.[43] In 1775, after the start of the Revolutionary War in Massachusetts, McDowell organised a Chester County Militia company, the 4th Battalion of Chester County Associators, and joined with Washington's army in time to defend New York City in 1776.[43] In 1785, having served throughout the war, McDowell was appointed captain of a Light Horse Brigade in Chester County, a largely ceremonial role for duties such as escorting general/president Washington when he travelled through the area.[43] McDowell died on 12 September 1815 and is buried at New London Presbyterian Church cemetery, Chester County.[43][44]

William Richardson (1866–1963) – Unionist representative for Magherafelt on Londonderry County Council until just after World War II.[45] He was one of the first people in South Londonderry to sign the Ulster Covenant, and on the 50th anniversary of the covenant in 1962 was given a commemorative rosette for being one of the oldest surviving signatories at the age of 92.[45] William Richardson was also a member of the Orange Order and the South Londonderry Unionist Association, as well as a founding member of Tobermore's Apprentice Boys of Derry club.[45] As a Free Mason, he was: Past Senior Grand Warden of the Provincial Grand Lodge of Derry and Donegal; Past Master of Tobermore's Eureka Masonic Lodge 309; and Past King of Curran Royal Arch Chapter 532.[45] On a religious level William Richardson was a member of Kilcronaghan parish church's Select Vestry, a parochial nominator, and held the office of treasurer.[45] When electricity came to Tobermore, he solely financed its installation in the local parish church.[45] He was held in such high esteem that his funeral was one of the largest seen in Magherafelt district for years.[45] Shortly after World War I, William's wife Mary, introduced the Poppy Appeal to Tobermore, having lost her brother in the Battle of the Somme.[46]

Walter Lyle Richardson (1913–1990) – President of the Magherafelt Royal British Legion, Bridge End United Football Club, and the Diamond Bar Darts Club.[46] Like his father William Richardson he was treasurer to the local parish church's Select Vestry, a role he held for 40 years.[46] During World War II he was a full-gunner in the 6th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Royal Artillery, also known as the "Coleraine Battery", seeing action throughout the Middle East and Europe, fighting in famous battles such as El Alamein and Monte Cassino, earning respect from his peers for his "exemplary courage".[46] After the war he worked tirelessly for the welfare of his former comrades devoting his energy to the Royal British Legion, and on Remembrance Day would lead the Magherafelt parade, take part in the Maghera parade and then lead the tributes in Tobermore.[46] For his services he was made president of the Magherafelt Royal British Legion upon the death of its previous president.[46] In 1988 he was awarded the Freedom of the Borough of Coleraine for his services as part of the Coleraine Battery in World War II.[46] His funeral was the largest seen in Tobermore for decades.[46]

Annie Stockman – Member of the Belgian resistance during World War II, performing non-combative duties, for which she and her comrades were acknowledged by the Red Cross.[47] Born in Brussels, she met her future husband, Sergeant Harry Stockman from Tobermore, after the Liberation of Brussels.[47] After the war they moved to Cookstown before settling down in Tobermore.[47]

Desmond Watters – Funeral director who starred in the 2004 Northern Irish movie, Mickybo and Me.[48] Having one of the only original 1970s hearses in the United Kingdom, the movie's production company contacted him for a loan of the hearse.[48] While filming, the director asked Watters for tips on how parts of the scene should be conducted, and later gave him the role of the funeral director in the movie.[48]

Hiram Parkes Wilkinson, BCL, KC (1866–1935) – Son of Sir Hiram Shaw Wilkinson (see below), who also served as a British judge and senior lawyer in the Far East. He was Crown Advocate in Shanghai from 1897 to 1925. He was concurrently Judge of the High Court of Weihaiwei from 1916 to 1925. Upon his retirement in 1925, Wilkinson moved to Moneyshanere. He founded the Tobermore Unionist Club,[27] which later became a branch of the Ulster Volunteers,[32] which itself became part of the 36th Ulster Division in World War I. Wilkinson became a King's Counsel in 1928. He returned to China in 1932 and died in Shanghai in 1935.

Sir Hiram Shaw Wilkinson, JP, DL (1840–1926) – Leading British judge and diplomat, who served in China and Japan. He went to Japan in 1864 as a student interpreter in the British Japan Consular Service. He served as Crown Advocate in Shanghai from 1881 to 1897. In 1897, he was then appointed Judge of the British Court for Japan and then in 1900 Chief Justice of the British Supreme Court for China and Corea. In 1905 he retired after 40 years service in the East and moved to the townland of Moneyshanere, outside Tobermore. He died in September 1926 in the village.[49]

Local culture

Every seven years the 12th of July Orange Order parade for the region is held in Tobermore,[50] the most recent being 2012.[51] On 2005, The Twelfth in Tobermore saw the participation of the Birmingham Sons of William LOL 1003 from Birmingham, Alabama.[50] The Canadian Orange Order lodge Tobermore Crown and Bible Defenders LOL 2391, Toronto, is named after its Northern Irish counterpart. Its female counterpart is known as L.O.B.A. (Ladies Orange Benevolent Association) Tobermore Lodge No. 740, Toronto, and has on their standard a painting of the Tobermore Church of Ireland with the caption: "Tobermore Parish Church, Co. Derry". As with many other settlements in Northern Ireland, Tobermore has what is known as the Eleventh night, the night before the 12 July Orange Order celebrations. The traditional activities of the Eleventh Night include the playing of Lambeg drums, the parading of the town by the local blood and thunder band and the lighting of a bonfire.

Local bands

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Tobermore also contains two flute bands; Tobermore Loyal F.B. and Blackhill F.B., both of which partake in the Unionist Marching Season. Previous bands include Tobermore Flute Band which was founded shortly after 1855 and was in existence until 1914 when it disbanded due to World War I.[24] It reformed after the war in 1918 and played until 1934. In 1934 the Duke of York Accordion Band was formed.[24] In 1981 an 85-year-old ticket for "A Grand Ball" in connection with Tobermore Flute Band was sent to the Mid-Ulster Mail for publication.[24] This ball was held on Friday evening, 23 October 1896.[24]

Millrow Flute Band was a former Tobermore blood and thunder band, founded in the early 1970s, disbanding in 2000.[52] It was during the 70s that the blood and thunder style became popular with loyalist bands. Millrow used the style to quickly became one of the biggest and most famous loyalist bands of the 1970s/80s.[52] In 1973, Millrow F.B. released an LP and also featured on a CD titled Ulster's Greatest Bands Meet, featuring three other flute bands, where Millrow contributed more tunes to the CD than any of the other three bands did on their own.[53]

Parades

According to the Parades Commission there were nine parades or processions in Tobermore in 2011,[54] twelve in 2012, which included the regional Twelfth celebrations,[55] and eight in 2013.[56] They range from the local flute band Tobermore Loyal, the Tobermore branch of the Walker Club of the Apprentice Boys of Derry, the Royal British Legion, the Royal Black Institution, the Boy's Brigade, and the local Orange Order lodge.[54][55][56]

Masonic order

Tobermore has its own Masonic Order lodge with the lodge name of Eureka and lodge number 309. At the time of its founding, Tobermore was commonly referred to as Tubbermore and lodge 309 is still referred to by the Masonic Order as being situated in Tubbermore.[57]

In 1747, a warrant was issued for the creation of a Dublin Masonic Lodge, lodge number 169. On 5 September 1765, this warrant was cancelled, however by 7 March 1811, the 169 lodge had resurfaced in Magherafelt. On 1 December 1825, the 169 lodge was removed from Magherafelt to Tobermore, where by 1838 it had moved onto Moneymore. The 169 lodge since 1895 has been situated in Belfast.[58]

Politics

Tobermore lies within the Tobermore electoral ward of Magherafelt District Council's Sperrin electoral region.[59] Tobermore ward being the only ward in Sperrin with a Protestant majority[60] is regarded as the main base of support for the sole Unionist councillor elected for Sperrin since its inception (except in 1977 when two Unionist councillors where elected[61]). Between 1985 and 2005, the sole Unionist councillor elected for Sperrin was a Tobermore resident; 1985-1989 W. Richardson (Ulster Unionist Party);[62] 1989-2005 R. Montgomery (UUP, Independent).[63]

Tobermore has belonged to the following constituencies:

UK Parliament constituencies

- Londonderry - 1801-85 (abolished and divided into North and South Londonderry)

- South Londonderry - 1885-1922 (abolished and merged with North Londonderry)

- Londonderry - 1922-85

(abolished and divided into Foyle and East Londonderry)

- East Londonderry - 1985-95 (boundary change)

- Mid Ulster - 1995–present

Northern Ireland Parliament constituencies

- Londonderry - 1921-29 (abolished)

- South Londonderry - 1929-73 (abolished)

Northern Ireland Assembly constituencies

- Mid-Ulster - 1998–present

Northern Ireland local government

- Magherafelt Poor Law Union - 1838-98

- Magherafelt Rural Sanitary District - 1878-98

- Magherafelt Rural District (Ireland) - 1898-1921

- Magherafelt Rural District (Northern Ireland) - 1921-73

- Magherafelt District Council - 1973-

- Mid-Ulster District Council - proposed new district

Demography

Education

Prior to the establishment of national primary schools, education lay mainly in the hands of the church. In Tobermore the Church of Ireland parish of Kilcronaghan has records of its school masters going as far back as Mr. Alex Trotter in 1686. The Parish School was originally built in the townland of Granny on the leading road between Tobermore and Draperstown.[31] Despite being a Church of Ireland Parish School, it was open to children of all denominations. In 1836, there were 70 children recorded on the roll with 28 being described as Church of Ireland, 20 Presbyterian, 2 Roman Catholic, and 20 "other denominations". Secular education such as arithmetic was taught as well as English. The local Presbyterian Church would also found its own school held in the Session House at the rear of the Presbyterian meeting house. Private session classes for adults would also be held twice a week in the Presbyterian Session House.[31]

Tobermore's first public school was established in 1817 in a room which was formerly a public house. It received an income from the London Hibernian Society as well as books published by them such as Thompson and Gough's Arithmetic and Murray's English Grammer. This school is now the present-day Tobermore Primary School. In 1826, Killytoney National School was established. It was built on the old leading road between Tobermore and Desertmartin., and has been connected to the National Board since 1833.[31] During this time, there were also another seven schools in Kilcronaghan Parish; four female schools, one of which in the townland of Brackagh Rowley (sic) was an Irish speaking school; an Irish male school; and two national schools. By 1967, Kilcronaghan Parish School had closed and was almagated with Black Hill School and Sixtowns School to become the present-day Kilross Primary School.[31]

There are two schools in the Tobermore area:

- Tobermore Primary School, located within the North Eastern Education and Library Board area.[64]

- Kilross Primary School, located within the North Eastern Education and Library Board area.[65]

For secondary education, students from the Tobermore electoral ward mainly attend schools in Magherafelt and to a lesser degree Draperstown.[66] Tobermore ward also has the highest education performance of any ward within Magherafelt District Council, with 88.8% of students achieving 5 or more GCSEs at grades of C+ or higher in 2008. This is compared to averages of: 71.8% for Magherafelt District Council; 70.1% for Mid-Ulster parliamentary constituency; and 66.9% for Northern Ireland.[66]

Sport

Tobermore United Football Club is the local football club. They finished the 2010-11 IFA Championship 2 league season as runners-up, gaining promotion to the IFA Championship 1 league. Tobermore United are most famous for being the only club George Best played competitively for in his home country.

The Tobermore No. 11 Northern Ireland Supporters Club was founded in the latter half of 2005. Its title contains No.11 as a dedication to George Best for it was the number that he wore when he played his one-off match for Tobermore United.

The village contains only one local dart team, the Diamond Bar Dart Team. In the 2004/2005 season they won the South Derry Darts 2nd Division League and South Derry 2nd Division League Cup.

The Tobermore Golf Driving Range, was opened in 1995, and is a two tier structure containing 34 bays.

See also

References

- ↑ Toner, Gregory: Place-Names of Northern Ireland, page 133-134. Queen's University of Belfast, 1996, ISBN 0-85389-613-5

- ↑ "Best Kept Award Winners". NI Amenity Council. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ "Results of 2009 Translink Ulster in Bloom Awards". Translink. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ↑ "Results of 2010 Translink Ulster in Bloom Awards". Translink. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ↑ "Results of 2011 Translink Ulster in Bloom Awards". Translink. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ↑ "Tobermore". The Northern Ireland Place-Name Project. Place Names NI. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ "Tobermore". Logaimn Placenames Project. Placenames Database of Ireland. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- 1 2 Library Ireland - Lewis's Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, 1837

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ordnance Survey Memoirs for the Parishes of Desertmartin and Kilcronaghan, Ballinascreen Historical Society. Published 1986

- ↑ "Designated and Proposed Ramsar sites in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 Toner, Gregory, Place-names of Northern Ireland - Volume Five, County Londonderry I, The Moyola Valley, p. 233. The Institute of Irish Studies, Queens University Belfast (1996); ISBN 0-85389-613-5

- 1 2 Planning Appeals Commission (3 October 2011). "Planning Appeals Commission NI" (PDF).

- 1 2 Statistical Reports of Six Derry Parishes 1821, John MacCloskey

- ↑ Mr. John O'Donovans Letters from County Londonderry (1834)

- ↑ Planning NI

- ↑ Bradley, John: The Irish Barn Church, pages 232-277. Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, Vol. 21/22, Vol. 21, no. 2 - Vol. 22, no. 1 (2007/2008)

- 1 2 3 "History of congregations of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland". Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 Patrick Kelly & Graham Mawhinney; Kilcronaghan Gravestone Inscriptions. Ballinscreen Historical Society, 2011. ISBN 978-0-9544341-8-2

- ↑ The Belfast Newsletter Index - 1737 to 1800

- ↑ Yeomanry Officers, Ireland, 1804. N6431. Linen Hall Library, Belfast.

- ↑ Yeomanry and Volunteer Infantry of Ireland, 1829. Linen Hall Library, Belfast.

- ↑ Yeomanry Officers, Ireland, 1834. N6430. Linen Hall Library, Belfast.

- 1 2 Statistical Reports of Six Derry Parishes 1821. Ballinascreen Historical Society, 1983.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mid-Ulster Mail 1981

- ↑ "The Orange Institution and the Ulster Unionist Council". Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ↑ BBC. "Ulster Unionist Council, 1905". Wars & Conflict - 1916 Easter Rising Profiles. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- 1 2 Tobermore Roll of Honour close-up detailing founder of Tobermore Unionist Club

- ↑ Brown, Reverend J. Walker; The Siege of Tobermore, 1912.

- ↑ The Union Cruiser lyrics

- ↑ "Historical notes". The Songs My Father Sung. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Richardson, Hilary; 150th Anniversary of Kilcronaghan Parish Church. Kilcronaghan Parish Church, 2008. ISBN 978-1-906689-05-6.

- 1 2 Tobermore Volunteers Roll of Honour

- ↑ The Derry and Antrim Year Book 1941

- 1 2 3 4 An Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Northern Ireland

- 1 2 3 "List of principal meetings and other events connected with the Free Presbyterian Church during September 1968" (PDF). Public Records Office of Northern Ireland. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Unionist Paramilitary Attacks

- ↑ Mid-Ulster Mail, Morton Newspapers Ltd., Thursday 5 August 2010 edition.

- ↑ Mid-Ulster Mail, Morton Newspapers Ltd., Thursday 19 August 2010 edition.

- ↑ "Five held in Tobermore murder probe". UTV. 1 August 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ "Two jailed over brutal murder that started with a spilt drink". Belfast Telegraph. 12 February 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ Moyola Angling - River Moyola Flood

- ↑ UUP Billy Armstrong - River Moyola Flood

- 1 2 3 4 "Descendants of Captain James McDowell & Elizabeth Loughead". Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ "Capt James McDowell". Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Northern Constitution, 9 March 1963. William Richardson obituary

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Northern Constitution, December 1990. Walter Lyle Richardson obituary

- 1 2 3 "The Annie Stockman Story". Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 "D Watters Funeral Services website". Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ Times obituary 29 September 1926, p. 14

- 1 2 Mid-Ulster Mail South Derry Edition, 14 July 2005, published by Morton Newspapers

- ↑ Mid-Ulster Mail South Derry Edition, 19 July 2012, published by Morton Newspapers

- 1 2 To The Beat of the Drum, Published by the Ulster Bands Association

- ↑ Union Jack Shop - Ulsters Greatest Bands Meet CD

- 1 2 "Parades Commission". Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Parades Commission". Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Parades Commission". Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ Masonic Lodges in County Londonderry

- ↑ Tower of Lebanon Lodge 169 - Freedom Masonic Lodge 169

- ↑ Wards by District Electoral Area and District Council Area

- ↑ Distribution of Catholic population in Northern Ireland, by Electoral Wards, 2001 Census

- ↑ Magherafelt District Council Elections 1973-1981

- ↑ Magherafelt District Council Elections 1985-1993

- ↑ Magherafelt District Council Elections 1993-2005

- ↑ Schools Web Directory entry for Tobermore Primary School

- ↑ Schools Web Directory entry for Kilross Primary School

- 1 2 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development; Tobermore Integrated Village Plan, October 2011