Tiabendazole

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Mintezol, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, topical |

| ATC code | D01AC06 (WHO) P02CA02 (WHO) QP52AC10 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Сmax 1–2 hours (oral administration) |

| Metabolism | GI tract |

| Biological half-life | 8 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (90%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

148-79-8 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5430 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7304 |

| DrugBank |

DB00730 |

| ChemSpider |

5237 |

| UNII |

N1Q45E87DT |

| KEGG |

D00372 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL625 |

| NIAID ChemDB | 007903 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.206 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H7N3S |

| Molar mass | 201.249 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Density | 1.103 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 293 to 305 °C (559 to 581 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Tiabendazole (INN, BAN), thiabendazole (AAN, USAN), TBZ (and the trade names Mintezol, Tresaderm, and Arbotect) is a fungicide and parasiticide.

Uses

Fungicide

It is used primarily to control mold, blight, and other fungal diseases in fruits (e.g. oranges) and vegetables; it is also used as a prophylactic treatment for Dutch elm disease.

Use in treatment of aspergillosis has been reported.[1]

Parasiticide

As an antiparasitic, it is able to control roundworms (such as those causing strongyloidiasis),[2] hookworms, and other helminth species which attack wild animals, livestock and humans.[3]

Angiogenesis inhibitor

Genes responsible for the maintenance of cell walls in yeast have been shown to be responsible for angiogenesis in vertebrates. Tiabendazole serves to block angiogenesis in both frog embryos and human cells. It has also been shown to serve as a vascular disrupting agent to reduce newly established blood vessels. Tiabendazole has been shown to effectively do this in certain cancer cells.[4]

Pharmacodynamics

TBZ works by inhibition of the mitochondrial, helminth-specific enzyme, fumarate reductase, with possible interaction with endogenous quinone.[5]

Other

Medicinally, thiabendazole is also a chelating agent, which means it is used medicinally to bind metals in cases of metal poisoning, such as lead, mercury, or antimony poisoning.

In dogs and cats, thiabendazole is used to treat ear infections.

Thiabendazole is also used as a food additive,[6][7] a preservative with E number E233 (INS number 233). For example, it is applied to bananas to ensure freshness, and is a common ingredient in the waxes applied to the skins of citrus fruits. It is not approved as a food additive in the EU,[8] Australia and New Zealand.[9]

Safety

The substance appears to have a slight toxicity in higher doses, with effects such as liver and intestinal disorders at high exposure in test animals (just below LD50 level). Some reproductive disorders and decreasing weaning weight have been observed, also at high exposure. Effects on humans from use as a drug include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, dizziness, drowsiness, or headache; very rarely also ringing in the ears, vision changes, stomach pain, yellowing eyes and skin, dark urine, fever, fatigue, increased thirst and change in the amount of urine occur. Carcinogenic effects have been shown at higher doses.[10]

Synthesis

Intermediate arylamidine 2 is prepared by the AlCl3 catalyzed addition of aniline to the nitrile function of 4-cyanothiazole (1). Amidine (2) is then converted to its N-chloro analog 3 by means of NaOCl. On base treatment, this apparently undergoes a nitrene insertion reaction (4) to produce thiabendazole (5). Note the direction of the arrow is from the benzene to the nitrene since the nitrene is an electrophilic species.

Alternative route of synthesis: 4-thiazolecarboxamide with o-phenylenediamine in polyphosphoric acid.[12]

Synthesis of labeled thiabendazole:[13]

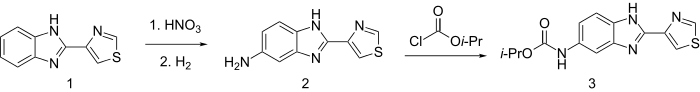

Analogues

Cambendazole (best of 300 agents in an extensive study),[16] is made by nitration of tiabendazole, followed by catalytic hydrogenation to 2, and acylation with Isopropyl chloroformate.

- Lobendazole

- Albendazole

- Oxfendazole

- Mebendazole

- Cyclobendazole

- Flubendazole (antiprotozoal agent)

- Dribendazole

Additionally, tiabendazole was noted to exhibit moderate anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities, which led to the development of KB-1043.

See also

References

- ↑ Upadhyay MP, West EP, Sharma AP (January 1980). "Keratitis due to Aspergillus flavus successfully treated with thiabendazole". Br J Ophthalmol. 64 (1): 30–2. doi:10.1136/bjo.64.1.30. PMC 1039343

. PMID 6766732.

. PMID 6766732. - ↑ Igual-Adell R, Oltra-Alcaraz C, Soler-Company E, Sánchez-Sánchez P, Matogo-Oyana J, Rodríguez-Calabuig D (December 2004). "Efficacy and safety of ivermectin and thiabendazole in the treatment of strongyloidiasis". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 5 (12): 2615–9. doi:10.1517/14656566.5.12.2615. PMID 15571478.

- ↑ Portugal R, Schaffel R, Almeida L, Spector N, Nucci M (June 2002). "Thiabendazole for the prophylaxis of strongyloidiasis in immunosuppressed patients with hematological diseases: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study". Haematologica. 87 (6): 663–4. PMID 12031927.

- ↑ Cha, HJ; Byrom M; Mead PE; Ellington AD; Wallingford JB; et al. (August 2012). "Evolutionarily Repurposed Networks Reveal the Well-Known Antifungal Drug Thiabendazole to Be a Novel Vascular Disrupting Agent". PLoS Biology. 10 (8): e1001379. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001379. PMC 3423972

. PMID 22927795. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

. PMID 22927795. Retrieved 2012-08-21. - ↑ Gilman, A.G., T.W. Rall, A.S. Nies and P. Taylor (eds.). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 8th ed. New York, NY. Pergamon Press, 1990., p. 970

- ↑ Rosenblum, C (March 1977). "Non-Drug-Related Residues in Tracer Studies". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 2 (4): 803–14. doi:10.1080/15287397709529480. PMID 853540.

- ↑ Sax, N.I. Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials. Vol 1-3 7th ed. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1989., p. 3251

- ↑ UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ↑ Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code"Standard 1.2.4 – Labelling of ingredients". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ↑ "Reregistration Eligibility Decision THIABENDAZOLE" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ Grenda, V. J.; Jones, R. E.; Gal, G.; Sletzinger, M. (1965). "Novel Preparation of Benzimidazoles from N-Arylamidines. New Synthesis of Thiabendazole1". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 30: 259–261. doi:10.1021/jo01012a061.

- ↑ Brown, H. D.; Matzuk, A. R.; Ilves, I. R.; Peterson, L. H.; Harris, S. A.; Sarett, L. H.; Egerton, J. R.; Yakstis, J. J.; Campbell, W. C.; Cuckler, A. C. (1961). "Antiparasitic Drugs. Iv. 2-(4'-Thiazolyl)-Benzimidazole, A New Anthelmintic". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 83 (7): 1764–1765. doi:10.1021/ja01468a052.

- ↑ Tocco, D. J.; Buhs, R. P.; Brown, H. D.; Matzuk, A. R.; Mertel, H. E.; Harman, R. E.; Trenner, N. R. (1964). "The Metabolic Fate of Thiabendazole in Sheep1". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 7 (4): 399–405. doi:10.1021/jm00334a002.

- ↑ Hoff, Fisher, ZA 6800351 (1969 to Merck & Co.), C.A. 72, 90461q (1970).

- ↑ Hoff, D. R.; Fisher, M. H.; Bochis, R. J.; Lusi, A.; Waksmunski, F.; Egerton, J. R.; Yakstis, J. J.; Cuckler, A. C.; Campbell, W. C. (1970). "A new broad-spectrum anthelmintic: 2-(4-Thiazolyl)-5-isopropoxycarbonylamino-benzimidazole". Experientia. 26 (5): 550–551. doi:10.1007/BF01898506.

- ↑ Chronicles of Drug Discovery, Book 1, pp 239-256.