Space Shuttle thermal protection system

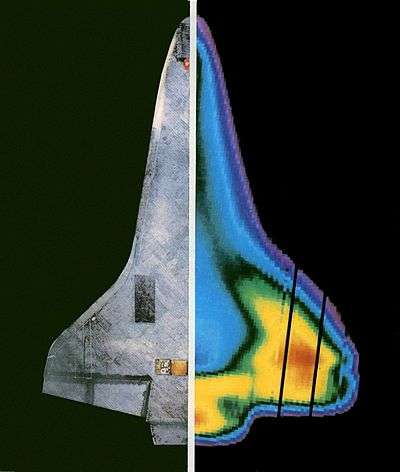

The Space Shuttle thermal protection system (TPS) is the barrier that protected the Space Shuttle Orbiter during the searing 1,650 °C (3,000 °F) heat of atmospheric reentry. A secondary goal was to protect from the heat and cold of space while in orbit.[1]

Materials

The TPS covered essentially the entire orbiter surface, and consisted of seven different materials in varying locations based on amount of required heat protection:

- Reinforced carbon–carbon (RCC), used in the nose cap, the chin area between the nose cap and nose landing gear doors, the arrowhead aft of the nose landing gear door, and the wing leading edges. Used where reentry temperature exceeded 1,260 °C (2,300 °F).

- High-temperature reusable surface insulation (HRSI) tiles, used on the orbiter underside. Made of coated LI-900 Silica ceramics. Used where reentry temperature was below 1260 °C.

- Fibrous refractory composite insulation (FRCI) tiles, used to provide improved strength, durability, resistance to coating cracking and weight reduction. Some HRSI tiles were replaced by this type.

- Flexible Insulation Blankets (FIB), a quilted, flexible blanket-like surface insulation. Used where reentry temperature was below 649 °C (1,200 °F).

- Low-temperature Reusable Surface Insulation (LRSI) tiles, formerly used on the upper fuselage, but were mostly replaced by FIB. Used in temperature ranges roughly similar to FIB.

- Toughened unipiece fibrous insulation (TUFI) tiles, a stronger, tougher tile which came into use in 1996. Used in high and low temperature areas.

- Felt reusable surface insulation (FRSI). White Nomex felt blankets on the upper payload bay doors, portions of the mid fuselage and aft fuselage sides, portions of the upper wing surface and a portion of the OMS/RCS pods. Used where temperatures stayed below 371 °C (700 °F).

Each type of TPS had specific heat protection, impact resistance, and weight characteristics, which determined the locations where it was used and the amount used.

The shuttle TPS has three key characteristics that distinguish it from the TPS used on previous spacecraft:

- Reusable. Previous spacecraft generally used ablative heat shields which burned off during reentry and so couldn't be reused. This insulation was robust and reliable, and the single-use nature was appropriate for a single-use vehicle. By contrast, the reusable shuttle required a reusable thermal protection system.

- Lightweight. Previous ablative heat shields were very heavy. For example the ablative heat shield on the Apollo Command Module comprised about 1/3 of the vehicle weight. The winged shuttle had much more surface area than previous spacecraft, so a lightweight TPS was crucial.

- Fragile. The only known technology in the early 1970s with the required thermal and weight characteristics was also so fragile, due to the very low density, that one could easily crush a TPS tile by hand.

Why TPS is needed

The orbiter's aluminum structure could not withstand temperatures over 175 °C (347 °F) without structural failure.[2] Aerodynamic heating during reentry would push the temperature well above this level in areas, so an effective insulator was needed.

Reentry heating

Reentry heating differs from the normal atmospheric heating associated with jet aircraft, and this governed TPS design and characteristics. The skin of high-speed jet aircraft can also become hot, but this is from frictional heating due to atmospheric friction, similar to warming one's hands by rubbing them together. The orbiter reentered the atmosphere as a blunt body by having a very high (40-degree) angle of attack, with its broad lower surface facing the direction of flight. Over 80% of the heating the orbiter experiences during reentry is caused by compression of the air ahead of the hypersonic vehicle, in accordance with the basic thermodynamic relation between pressure and temperature. A hot shock wave was created in front of the vehicle, which deflected most of the heat and prevented the orbiter's surface from directly contacting the peak heat. Therefore reentry heating was largely convective heat transfer between the shock wave and the orbiter's skin through superheated plasma.[1] The key to a reusable shield against this type of heating is very low-density material, similar to how a thermos bottle inhibits convective heat transfer.

Some high temperature metal alloys can withstand reentry heat; they simply get hot and re-radiate the absorbed heat. This technique, called "heat sink" thermal protection, was planned for the X-20 Dyna-Soar winged space vehicle.[1] However, the amount of high-temperature metal required to protect a large vehicle like the Space Shuttle Orbiter would have been very heavy and entailed a severe penalty to the vehicle's performance. Similarly, ablative TPS would be heavy, possibly disturb vehicle aerodynamics as it burned off during reentry, and require significant maintenance to reapply after each mission. (Unfortunately, TPS tile, which was originally specified never to take debris strikes during launch, in practice also needed to be closely inspected and repaired after each landing, due to damage invariably incurred during ascent, even before new on-orbit inspection policies were established following the loss of Space Shuttle Columbia.)

Detailed description

The TPS was a system of different protection types, not just silica tiles. They are in two basic categories: tile TPS and non-tile TPS.[1] The main selection criteria used the lightest weight protection capable of handling the heat in a given area. However in some cases a heavier type was used if additional impact resistance was needed. The FIB blankets were primarily adopted for reduced maintenance, not for thermal or weight reasons.

Much of the shuttle was covered with LI-900 silica tiles, made from essentially very pure quartz sand.[1] The insulation prevented heat transfer to the underlying orbiter aluminum skin and structure. These tiles were such poor heat conductors that one could hold one by the edges while it was still red hot.[3] There were about 24,300 unique tiles individually fitted on the vehicle, for which the orbiter has been called "the flying brickyard". Researchers at University of Minnesota and Pennsylvania State University are performing the atomistic simulations to obtain accurate description of interactions between atomic and molecular oxygen with silica surfaces to develop better high-temperature oxidation-protection systems for leading edges on hypersonic vehicles.[4]

The tiles were not mechanically fastened to the vehicle, but glued. Since the brittle tiles could not flex with the underlying vehicle skin, they were glued to Nomex felt Strain Isolation Pads (SIPs) with RTV silicone adhesive, which were in turn glued to the orbiter skin. These isolated the tiles from the orbiter's structural deflections and expansions.[1]

Tile types

High-temperature reusable surface insulation (HRSI)

_tile%2C_c_1980._(9663807484).jpg)

HRSI tiles (black in color) provided protection against temperatures up to 1,260 °C (2,300 °F). There were 20,548 HRSI tiles which covered the landing gear doors, external tank umbilical connection doors, and the rest of the orbiter's under surfaces. They were also used in areas on the upper forward fuselage, parts of the orbital maneuvering system pods, vertical stabilizer leading edge, elevon trailing edges, and upper body flap surface. They varied in thickness from 1 to 5 inches (2.5 to 12.7 cm), depending upon the heat load encountered during reentry. Except for closeout areas, these tiles were normally 6 by 6 inches (15 by 15 cm) squares. The HRSI tile was composed of high purity silica fibers. Ninety percent of the volume of the tile was empty space, giving it a very low density (9 lb/cu ft or 140 kg/m3) making it light enough for spaceflight.[1] The uncoated tiles were bright white in appearance and looked more like a solid ceramic than the foam-like material that they were.

The black coating on the tiles was Reaction Cured Glass (RCG) of which tetrasilicide and borosilicate glass were some of several ingredients. RCG was applied to all but one side of the tile to protect the porous silica and to increase the heat sink properties. The coating was absent from a small margin of the sides adjacent to the uncoated (bottom) side. To waterproof the tile, dimethylethoxysilane was injected into the tiles by syringe. Densifying the tile with tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) also helped to protect the silica and added additional waterproofing.

.png)

An uncoated HRSI tile held in the hand feels like a very light foam, less dense than styrofoam, and the delicate, friable material must be handled with extreme care to prevent damage. The coating feels like a thin, hard shell and encapsulates the white insulating ceramic to resolve its friability, except on the uncoated side. Even a coated tile feels very light, lighter than a same-sized block of styrofoam. As expected for silica, they are odorless and inert.

HRSI was primarily designed to withstand transition from areas of extremely low temperature (the void of space, about −270 °C or −454 °F) to the high temperatures of re-entry (caused by interaction, mostly compression at the hypersonic shock, between the gases of the upper atmosphere & the hull of the Space Shuttle, typically around 1,600 °C or 2,910 °F).[1]

Fibrous Refractory Composite Insulation Tiles (FRCI)

The black FRCI tiles provided improved durability, resistance to coating cracking and weight reduction. Some HRSI tiles were replaced by this type.[1]

Toughened unipiece fibrous insulation (TUFI)

A stronger, tougher tile which came into use in 1996. TUFI tiles came in high temperature black versions for use in the orbiter's underside, and lower temperature white versions for use on the upper body. While more impact resistant than other tiles, white versions conducted more heat which limited their use to the orbiter's upper body flap and main engine area. Black versions had sufficient heat insulation for the orbiter underside but had greater weight. These factors restricted their use to specific areas.[1]

Low-temperature reusable surface insulation (LRSI)

White in color, these covered the upper wing near the leading edge. They were also used in selected areas of the forward, mid, and aft fuselage, vertical tail, and the OMS/RCS pods. These tiles protected areas where reentry temperatures are below 1,200 °F (649 °C). The LRSI tiles were manufactured in the same manner as the HRSI tiles, except that the tiles were 8 by 8 inches (20 by 20 cm) squares and had a white RCG coating made of silica compounds with shiny aluminum oxide.[1] The white color was by design and helped to manage heat on orbit when the orbiter was exposed to direct sunlight.

These tiles were reusable for up to 100 missions with refurbishment (100 missions was also the design lifetime of each orbiter). They were carefully inspected in the Orbiter Processing Facility after each mission, and damaged or worn tiles were immediately replaced before the next mission. Fabric sheets known as gap fillers were also inserted between tiles where necessary. These allowed for a snug fit between tiles, preventing excess plasma from penetrating between them, yet allowing for thermal expansion and flexing of the underlying vehicle skin.

Prior to the introduction of FIB blankets, LRSI tiles occupied all of the areas now covered by the blankets, including the upper fuselage and the whole surface of the OMS pods. This TPS configuration was only used on Columbia and Challenger.

Non-tile TPS

Flexible Insulation Blankets/Advanced Flexible Reusable Insulation (FIB/AFRSI)

Developed after the initial delivery of Columbia and first used on the OMS pods of Challenger.[5] This white low-density fibrous silica batting material had a quilt-like appearance, and replaced the vast majority of the LRSI tiles. They required much less maintenance than LRSI tiles yet had about the same thermal properties. After their limited use on Challenger, they were used much more extensively beginning with Discovery and replaced many of the LRSI tiles on Columbia after the loss of Challenger.

Reinforced Carbon-Carbon (RCC)

The light gray material which withstood reentry temperatures up to 1,510 °C (2,750 °F) protected the wing leading edges and nose cap. Each of the orbiters’ wings had 22 RCC panels about 1⁄4 to 1⁄2 inch (6.4 to 12.7 mm) thick. T-seals between each panel allowed for thermal expansion and lateral movement between these panels and the wing.

RCC was a laminated composite material made from graphite rayon cloth and impregnated with a phenolic resin. After curing at high temperature in an autoclave, the laminate was pyrolized to convert the resin to carbon. This was then impregnated with furfural alcohol in a vacuum chamber, then cured and pyrolized again to convert the furfural alcohol to carbon. This process was repeated three times until the desired carbon-carbon properties were achieved.

To provide oxidation resistance for reuse capability, the outer layers of the RCC were coated with silicon carbide. The silicon-carbide coating protected the carbon-carbon from oxidation. The RCC was highly resistant to fatigue loading that was experienced during ascent and entry. It was stronger than the tiles and was also used around the socket of the forward attach point of the orbiter to the External Tank to accommodate the shock loads of the explosive bolt detonation. RCC was the only TPS material that also served as structural support for part of the orbiter's aerodynamic shape: the wing leading edges and the nose cap. All other TPS components (tiles and blankets) were mounted onto structural materials that supported them, mainly the aluminum frame and skin of the orbiter.

Nomex Felt Reusable Surface Insulation (FRSI)

This white, flexible fabric offered protection at up to 371 °C (700 °F). FRSI covered the orbiter's upper wing surfaces, upper payload bay doors, portions of the OMS/RCS pods, and aft fuselage.

Gap fillers

Gap fillers were placed at doors and moving surfaces to minimize heating by preventing the formation of vortices. Doors and moving surfaces created open gaps in the heat protection system that had to be protected from heat. Some of these gaps were safe, but there were some areas on the heat shield where surface pressure gradients caused a crossflow of boundary layer air in those gaps.

The filler materials were made of either white AB312 fibers or black AB312 cloth covers (which contain alumina fibers). These materials were used around the leading edge of the nose cap, windshields, side hatch, wing, trailing edge of elevons, vertical stabilizer, the rudder/speed brake, body flap, and heat shield of the shuttle's main engines.

On STS-114, some of this material was dislodged and determined to pose a potential safety risk. It was possible that the gap filler could cause turbulent airflow further down the fuselage, which would result in much higher heating, potentially damaging the orbiter. The cloth was removed during a spacewalk during the mission.

Weight considerations

While RCC had the best heat protection characteristics, it was also much heavier than the silica tiles and FIB blankets, so it was limited to relatively small areas. In general the goal was to use the lightest weight insulation consistent with the required thermal protection. Weight per unit volume of each TPS type:

- RCC: 1986 kg/m³ (124 lb/ft³)

- LI-2200 tiles: 352 kg/m³ (22 lb/ft³)

- FRCI tiles: 192 kg/m³ (12 lb/ft³)

- LI-900 (black or white) tiles: 144 kg/m³ (9 lb/ft³)

- FIB blankets: 144 kg/m³ (9 lb/ft³)

Total area and weight of each TPS type (used on Orbiter 102) (pre-1996):[6]

| TPS type | color | Area(m2) | Areal Density(kg/m2) | Weight(kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRSI | white | 332.7 | 1.6 | 532.1 |

| LRSI | off white | 254.6 | 3.98 | 1014.2 |

| HRSI | black | 479.7 | 9.2 | 4412.6 |

| RCC | light gray | 38.0 | 44.7 | 1697.3 |

| misc | 918.5 | |||

| Total | 1105 | 8574.0 |

Early TPS problems

Slow tile application

Tiles often fell off and caused much of the delay in the launch of STS-1, the first shuttle mission, which was originally scheduled for 1979 but did not occur until April 1981. NASA was unused to lengthy delays in its programs, and was under great pressure from the government and military to launch soon. In March 1979 it moved the incomplete Columbia, with 7,800 of the 31,000 tiles missing, from the Rockwell International plant in Palmdale, California to Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Beyond creating the appearance of progress in the program, NASA hoped that the tiling could be finished while the rest of the orbiter was prepared. This was a mistake; some of the Rockwell tilers disliked Florida and soon returned to California, and the Orbiter Processing Facility was not designed for manufacturing and was too small for its 400 workers.[7]:83–87

Each tile used cement that required 16 hours to cure. After the tile was affixed to the cement, a jack held it in place for another 16 hours. In March 1979 it took each worker 40 hours to install one tile; by using young, efficient college students during the summer the pace sped up slightly, to 1.8 tiles per worker per week. Thousands of tiles failed stress tests and had to be replaced. By fall NASA realized that the speed of tiling would determine the launch date. The tiles were so problematic that officials would have switched to any other thermal protection method, but none other existed.[7]:88–91

Concern over "zipper effect"

The tile TPS was an area of concern during shuttle development, mainly concerning adhesion reliability. Some engineers thought a failure mode could exist whereby one tile could detach, and resulting aerodynamic pressure would create a "zipper effect" stripping off other tiles. Whether during ascent or reentry, the result would be disastrous.

Concern over debris strikes

Another problem was ice or other debris impacting the tiles during ascent. This had never been fully and thoroughly solved, as the debris had never been eliminated, and the tiles remained susceptible to damage from it. NASA's final strategy for mitigating this problem was to aggressively inspect for, assess, and address any damage that may occur, while on orbit and before reentry, in addition to on the ground between flights.

Early tile repair plans

These concerns were sufficiently great that NASA did significant work developing an emergency-use tile repair kit which the STS-1 crew could use before deorbiting. By December 1979, prototypes and early procedures were completed, most of which involved equipping the astronauts with a special in-space repair kit and a jet pack called the Manned Maneuvering Unit, or MMU, developed by Martin Marietta.

Another element was a maneuverable work platform which would secure an MMU-propelled spacewalking astronaut to the fragile tiles beneath the orbiter. The concept used electrically-controlled adhesive cups which would lock the work platform into position on the featureless tile surface. About one year before the 1981 STS-1 launch, NASA decided the repair capability was not worth the additional risk and training, so discontinued development.[8] There were unresolved problems with the repair tools and techniques; also further tests indicated the tiles were unlikely to come off. The first shuttle mission did suffer several tile losses, but they were fortunately in non-critical areas, and no "zipper effect" occurred.

Columbia accident and aftermath

On February 1, 2003, the Space Shuttle Columbia was destroyed on reentry due to a failure of the TPS. The investigation team found and reported that the probable cause of the accident was that during launch, a piece of foam debris punctured an RCC panel on the left wing's leading edge and allowed hot gases from the reentry to enter the wing and disintegrate the wing from within, leading to eventual loss of control and breakup of the shuttle.

The Space Shuttle's thermal protection system received a number of controls and modifications after the disaster. They were applied to the three remaining shuttles, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour in preparation for subsequent mission launches into space.

On 2005's STS-114 mission, in which Discovery made the first flight to follow the Columbia accident, NASA took a number of steps to verify that the TPS was undamaged. The 50-foot-long (15 m) Orbiter Boom Sensor System, a new extension to the Remote Manipulator System, was used to perform laser imaging of the TPS to inspect for damage. Prior to docking with the International Space Station, Discovery performed a Rendezvous Pitch Maneuver, simply a 360° backflip rotation, allowing all areas of the vehicle to be photographed from ISS. Two gap fillers were protruding from the orbiter's underside more than the nominally allowed distance, and the agency cautiously decided it would be best to attempt to remove the fillers or cut them flush rather than risk the increased heating they would cause. Even though each one protruded less than 3 cm (1.2 in), it is believed that leaving them in that state could cause heating increases of 25% upon reentry.

Because the orbiter did not have any handholds on its underside (as they would cause much more trouble with reentry heating than the protruding gap fillers of concern), astronaut Stephen K. Robinson worked from the ISS's robotic arm, Canadarm2. Because the TPS tiles were quite fragile, there had been concern that anyone working under the vehicle could cause more damage to the vehicle than was already there, but NASA officials felt that leaving the gap fillers alone was a greater risk. In the event, Robinson was able to pull the gap fillers free by hand, and caused no damage to the TPS on Discovery.

Tile Donations

As of 2010, with the impending Space Shuttle retirement, NASA is donating TPS tiles to schools, universities, and museums for the cost of shipping; US$23.4 each.[9] About 7000 tiles were available on a first-come, first-served basis, but limited to one each per institution.[9]

See also

| Wikinews has related news: 'Gouge' found on wing of Space Shuttle Endeavour |

References

- ”When the Space Shuttle finally flies”, article written by Rick Gore. National Geographic (pp. 316–347. Vol. 159, No. 3. March 1981).

- Space Shuttle Operator's Manual, by Kerry Mark Joels and Greg Kennedy (Ballantine Books, 1982).

- The Voyages of Columbia: The First True Spaceship, by Richard S. Lewis (Columbia University Press, 1984).

- A Space Shuttle Chronology, by John F. Guilmartin and John Mauer (NASA Johnson Space Center, 1988).

- Space Shuttle: The Quest Continues, by George Forres (Ian Allen, 1989).

- Information Summaries: Countdown! NASA Launch Vehicles and Facilities, (NASA PMS 018-B (KSC), October 1991).

- Space Shuttle: The History of Developing the National Space Transportation System, by Dennis Jenkins (Walsworth Publishing Company, 1996).

- U.S. Human Spaceflight: A Record of Achievement, 1961-1998. NASA - Monographs in Aerospace History No. 9, July 1998.

- "Space Shuttle Thermal Protection System" by Gary Milgrom. February, 2013. Free iTunes ebook download. https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/space-shuttle-thermal-protection/id591095660?mt=11

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jenkins, Dennis R. (2007). Space Shuttle: The History of the National Space Transportation System. Voyageur Press. p. 524 pages. ISBN 0-9633974-5-1.

- ↑ Day, Dwayne A. "Shuttle Thermal Protection System (TPS)". U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission.

- ↑ Gore, Rick (March 1981). "When the Space Shuttle Finally Flies". National Geographic. National Geographic. 159 (3): 316–347. Retrieved 2012-12-20.

- ↑ Anant D. Kulkarni, Donald G. Truhlar, Sriram Goverapet Srinivasan, Adri C. T. van Duin, Paul Norman, and Thomas E. Schwartzentruber (2013). "Oxygen Interactions with Silica Surfaces: Coupled Cluster and Density Functional Investigation and the Development of a New ReaxFF Potential". J. Phys. Chem. C. 117: 258. doi:10.1021/jp3086649.

- ↑ "STS-6 Press Information" (PDF). Rockwell International - Space Transportation & Systems Group. March 1983. p. 7. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

Orbital maneuvering system/reaction control system low temperature reusable surface insulation tiles (LRSI) replaced with advanced flexible reusable surface insulation (AFRSI) consisting of a sewn composite quilted fabric blanket with same silica tile material sandwiched between outer and inner blanket.

- ↑ File:ShuttleTPS2-colored.png

- 1 2 Lewis, Richard S. (1984). The voyages of Columbia: the first true spaceship. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-05924-8.

- ↑ Houston Chronicle, March 9, 2003

- 1 2 "NASA offers space shuttle tiles to school and universities". December 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08.

External links

- https://web.archive.org/web/20060909094330/http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov:80/kscpao/nasafact/tps.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110707103505/http://ww3.albint.com/about/research/Pages/protectionSystems.aspx

- http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/technology/sts-newsref/sts_sys.html

- http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/nexgen/Nexgen_Downloads/Shuttle_Gordon_TPS-PUBLIC_Appendix.pdf