Tel Rumeida

Tel Rumeida/Jabla al Rahama[1] (Arabic: تل رميدة; Hebrew: תל רומיידה) is an agricultural and residential area in the West Bank city of Hebron. Within it lies an archaeological tell whose remains go back to the Chalcolithic period. It may have been a Canaanite royal city. Some Jewish scholars believe it was the location of biblical Hebron.[2] It is also the location of a Palestinian neighbourhood[3] and an Israeli settlement.[4]

The international community considers Israeli settlements in the West Bank illegal under international law, but the Israeli government disputes this.[5]

Topological Description

Tel Rumeida is an agricultural and residential location on a slope to the west of Hebron's old quarter, running down east from Jebel Rumeida. On the east there is a spring, 'Ain Judēde.[6] It lies at the edge of the zone, H2, and extends into a Palestinian quarter. Several Palestinian homes lie on the tel's apex, a further cluster lies north, and to the east by Ein Jadide. Lower down, to the north-east, are 3 parallel thick-walled vaults called es Sakawati, and slightly bfurther east the tomb of Sheikh al Mujahid/ Abu es Sakawati.[7]

Much of the land is owned or worked by several Palestinian families, among them the Natshe and Abu Haikals. Three lots of land are regarded as in Jewish ownership, having been purchased in the 19th century by the old Jewish Hebronite community:2, lots 52 and 53, to the north, and one the south side. The Jewish settlement is called, Jesse's Lands (Admot Yishai). A Karaite cemetery, called er Rumeidy exists to the north-west,[8] containing some 500 tombs.[7]

Archaeology

Tel Rumeida is the oldest site in the city of Hebron.[9] Pringle suggests that the site excavated 200–300 metres east of the hilltop mosque represents the old Kiryat Arba described by the Dominican pilgrim Burchard of Mount Sion in 1293 as vetus civitas quondam Cariatharbe dicta.[10]

Excavations were carried out in the 1960s, and in the 1980s at Tel Rumeida in an area where ownership is contested between Palestinians and Jews. During the Jordanian occupation, excavations, were undertaken by Philip C. Hammond (1964-1966),[11] and later, after the Israeli occupation, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin authorized archaeological digs on Jewish lots, reportedly to preempt the expansion of settlements there, and these were conducted by the Judean Hill Country Expedition under Avi Ofer.[11] A third wave of excavation was undertaken in 2014, above Admot Yishai and between the Palestinian homes, with the intention of creating an archaeological parkland.[8] The new excavations began as a result of a settler initiative, which had been turned down by several prominent Israeli archaeologists, but was accepted by Emanuel Eisenberg of the Israel Antiquities Authority and David Ben-Shlomo of Ariel University, in a project that secured state funding.[12] For Eyal Weizman, Tel Rumeida has become 'the most literal embodiment of the relationship of Israeli settlements to archaeology'.[13] Archaeologist Yonathan Mizrachi argues that settler pressure to create an archaeological park in Tel Rumeida is a technique for taking over the terrain and asserting their power and legitimacy in the area.[14] Dr. Ahmed Rjoub, the Palestinian Authority's director of the Department of Site Management, claims that the excavations have removed artifacts attesting to both the Roman and Islamic heritage.[14]

The settlement dates back to at least the Chalcolithic era ca. 3,500 BCE., and the occupational sequence is very similar to Jerusalem's.[15] During the Early Bronze III (2800-2500 BCE) the settlement expanded, with a fortified area extending over 30 dunams. This was subsequently abandoned until, in the Middle Bronze I-II periods (2000-1600) it was reoccupied and rebuilt,[8] and girded by cyclopean walls built with stones measuring 3 by 5 metres.[16] A cuneiform economic text, with 4 personal names and a list of animals,[17] unearthed at the site and dated 17-16 century BCE indicates Tel Rumeida/Hebron was composed of a multicultural pastoral society of Hurrians and Amorites, run by an independent administrative system with its palace scribes perhaps under kingly rule.[8][18] The Late Bronze Age (1600-1200) levels have yielded no sign of settlement, aside from a few graves,one of which appears however to have been in continuous use from the LBA through to the Iron Age.[9] Neither Tel Rumeida nor the surrounding Hebron area show signs of settlement at this time, throughout this period, when the centre of the region was located in biblical Debir/Khirbet Rabud.[19] Tel Rumeida only revived with Iron Age I and IIA (1200-1000), with structures attesting to a small settlement in the transition from LBA to IA1.[8][19] Ofer infers on the basis of some material excavated to the north that this was a "Golden Age for Hebron", characterized by intensive settlement (11-10 B.C.E.[20]

For 2 centuries there is an absence of finds, until signs of a third phase of settlement, in a period when Hebron formed part of Judea, emerge in the 8th century BCE,[8] above the EBIII and MBII fortified city are 8th-century BCE four room houses, granaries and stamps "for the king of Hebron" (lmlk ḫbrn) on jar handles.[21] Fragments of jars and burnished vessels may suggest that there was a small-scale occupation.[8][15] This settlement was destroyed in 586 BCE,[8] and the city lay abandoned in the Persian period[22] until a new settlement arose during Hellenistic and Roman periods (350 BCE-Ist century CE). The town was part of Idumea. The late Roman period sees a new settlement (3-4th centuries CE) that survived into the Byzantine period, by which time the centre of the city moved from Tel Rumeida to what is now the old City of Hebron.[8]

After a lapse of over a decade, since January 2014, the Israeli Antiquities Authority has renewed excavations in the lots with attested Jewish ownership, which extends over a 6 dunam area,[23] In lot 52, other than ancient walls and agricultural implements, Muslim tombs were uncovered, and removed from the site. Lot 53 yielded a large, early Roman period large compound.[24]

Mosque of the Forty/Tomb of Jesse and Ruth

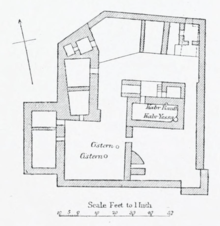

On the top of Tel Rumeida (Jabal Rumeida) are to be found three distinct edifices, consisting of 2 ruins and a tomb complex. One is Mashhad al-Arba’in, a mosque called in medieval times the Sanctuary(Mashhad) of the Forty, where mashad refers to martyrs, and is described by Mujir al-Din, in his History of Jerusalem and Hebron (c.1495).[10] as a pilgrimage site visited by pious Muslims (Ziyārah).[25] This site began to be called D(a)ir al-Arba'in (Mosque of the Forty (Witnesses)) by the 19th century.[25] Palestinians trace it back to the times of Saladin.[26] Both names, Mashhad al-Arba’in and Dayr al-Arba’in, appear to reflect the ancient name for Hebron, Qiryat Arba’, and thus would not refer to forty martyrs.[25]

The ruin, surrounded by a quadrangular wall structure and vaulted rooms, consisted of a single cell chapel and semi-circular apse measuring 5.5 by 10 metres. A tomb therein bears the inscription 1254 C.E.[10] It is sited above what was formerly known as the 'Ain Khibra, renamed the 'Ain Judaida. Juan Perera, a Franciscan writing ca.1553, described what was known in the Christian tradition as the Church of the Forty Martyrs, (Ecclesia quadraginta martyrum),[27] which had been transformed into a mosque,[28] and was apparently associated with Cain's murder of Abel.

Early Christian sources, such as Eusebius in his Onomasticon and Jerome, place Jesse's tomb, together with David's, in Bethlehem, which the Tanakh identifies as his place of origin.[29][30] There is no evidence of its use by Christians in the medieval period.[10] Rabbi Jacob, the Messenger of Yechiel of Paris, around 1238-1244, stated that either Jesse or Joab was buried in a cave on this Hebron hillsite.[31] The Italian Jewish traveler Meshulam de Volterra stated that the tomb of Jesse he visited was located 10 miles from Hebron.[32] In 1522-3 Rabbi Moses ben Mordecai Bassola visited the site, mentioning only Jesse’s tomb in a burial cave, putatively, in local folklore, connected by tunnel to the Cave of the Patriarchs.[33] Francesco Quaresmi in the early 17th century, described its remains as the chancel of the earlier church,[10] and observed that Turks and Orientals generally held this structure,[7][27] to be the tomb of Isai (Jesse),the legendary father of David in biblical lore. Within a small mosque, visitors were shown the qabr yissā and qabr ruth, respectively the tombs of Jesse and Ruth. These identifications are, according to Moshe Sharon, rather late since they are not mentioned by the Arab medieval writer Mujir al-Din.[25] Ruth’s tomb only began to be pointed out at the outset of the 19th century.[25] Quaresmi also describes in its proximity a terebinth tree and a spring within a cavern, whose waters were thought by local Hebronites to have curative powers.

The Hebron settlers, carrying on an earlier Hebronite Jewish tradition of reverence for the place,[7] view the site as one where Jesse, the legendary father of King David, and David's great grandmother, Ruth the Moabite, were buried. Many Western travelers' accounts only mention the site in connection with Jesse,[34][35][36][37][38] and at least one dismisses it as a site of superstitious veneration commenting:’ We need not believe that we see Jesse’s tomb, for he probably was buried with his fathers at Bethlehem’.[39]

Left-wing archaeological critics view the excavations on the site as pretexts for expanding the settlement -Ir David and Susya are compared- a form of 'annexation in the guise of archaeology'.[23][40][41] The Dir al-Arba'in was, according to Platt, probably built to fulfill two functions, that of a fortress and government building.[8][42][43]) A Torah scroll placed inside it by settlers has been removed by the IDF,[42][44] and the site was vandalized in 2007.[45] The tombs ascribed to Jesse and Ruth are visited frequented, especially during Shavuot, by Jews and converts to Judaism.[46]

The tomb of as-Saqawātī

Lower down the hill there are 3 parallel vaults in an olive grove at the eastern end of which is a tomb called as-Saqawātī next to a mulberry tree bearing an Arabic inscription which refers to a certain Sayyid or lineal descendent of Mohammad by the name Muḥammad Ibn ‘Abdallah al-Ḥusayni, from whom a Hebronite clan, the Āl ash-Sharīf claim descent, saying he was a Magrebi Arab from the as-Sāqiyah al-Ḥamrā’, from which his nisba, or onomastic for place of descent, seen in the tomb’s local name, Saqawātī ,is derived. According to this story, the person arrived in Jerusalem with Saladin in 1187, taught at Al-Aqsa and then settled in Hebron—Moshe Sharon suspects this story is a fabrication by the clan. A local legend has it that it lies in the open because all roofs built over it would collapse, and the site is still a place for prayers, esp. in times of drought.[25]

Modern era

In 1807, a Sephardic immigrant from Egypt, Rabbi Haim Yeshua Hamitzri (Haim the Jewish Egyptian) purchased 5 dunams on the periphery of the Old City, and, in 1811, signed two lease contracts for 800 dunams of land, among which were 4 plots at Tel Rumeida. The duration of the lease was 99 years. Since his descendant Haim Bajaio, the last Sephardic rabbi in the city, administered it after the Jews left Hebron, it is believed that the lease must have been renewed. These properties were appropriated by the Jordanian government in 1948, and the Israeli government in 1967. It is on the basis of the original lease taken out for 99 years by Haim Yeshia Hamitzri that settlers, none of whom is related to the original lessee, then asserted a claim to the land in Tel Rumeida, a claim dismissed by Haim Hanegbi, a founder of Matzpen, who argue that settlers in Hebron have no right to speak in the name of the old Jewish families of the city.[43][47] The Israeli Supreme Court ruled in 2011 that Jews have no right to properties they possessed in places like Hebron and Tel Rumeida before 1948.[48]

According to Abu Haikel, he rented the land from Jordanian government's Custodian of Enemy Property. After 1967, a new lease was signed with Israeli government's Custodian of Absentee Property. In 1981 the Custodian refused to charge the lease fees but later accepted the payment. Such incident reoccurred in 2001 and 2002.[49] The Haikel's land is subject to increasing encroachment by settlers on the basis of an archaeological claim. Summeer water delivery was secured by purchases frem the Hebron municipal water truck until frequent smashing of its windows by settlers forced the council to cancel the deliveries. Christian Peacemaker volunteers who tried to accompany the trucks were detained and received death threats.[50] The Israeli Custodian of Absentee Property refused to accept the Abu Haikal's rent payments in 1981, but, after an agreement was renegotiated in 2000, the back rent for 1981-2000 was reportedly paid up by the family, and fees were regularly accepted for the following 2 years, after which the land was declared a closed military zone, rent payments were rejected and the family was refused further access.[49]

Israeli settlement

The Ramat Yeshai settlement started in 1984, set up by settlers from Hebron who established 6 portable caravans at the Dir al-Arba'in (‘Assembly of Forty’) mosque. The initiative obtained official Israeli approval in 1998, and the Israel Defense Ministry gave the go-ahead for building 16 housing units on the site in 2001. Since then the land adjacent to the settlement is being incrementally taken over, notwithstanding stop-work orders handed down in judgements from the Israeli Supreme Court.[51] Both the Abu Haikal and Abu Aisha families had saved and protected Jews from the slaughter of other Arabs during the 1929 Hebron massacre and the Israeli Interior Minister Yosef Burg had, according to Abu Aisha, specifically asked settlers not to harm the Abu Aisha for this reason in the early 80s.[52][53] According to Ehud Sprinzak, an Israeli counterterrorism specialist and expert in far-right Jewish groups,[54] "a small number of very radical Jewish families" settled in the area in the mid-1980s.[55] According to Muhammad Abu Aisha, relations with the original settlers were amicable until the arrival of two Kahanists, Baruch Marzel[56] and Noam Federman[57] who took up residence there.[53] On Marzel's arrival at Tel Rumeida he began to promote the ultra-nationalist Kahanist ideology, outlawed by Israeli law.[58]

Settlers are said to purposefully provoke Palestinian residents: numerous testimonies of continuous harassment have been collected from several Palestinian families such as the Abu 'Aisha,[53][59] the Shamsiyeh, whose 8-year-old daughter’s hair was reportedly set alight by a settler,[60] and the Azzeh.[61] Peace activists stationed in the area report frequent threats or acts of settler stoning at both activists and local residents who venture there, or who try to work their lands.[62] Palestinians cannot adequately defend themselves, because the settlement is defended by an entire company of the Israeli Defense Force.[55] An English graffiti reading 'Gas the Arabs', said to be the handiwork of the Jewish Defense League, has been sprayed on one of the streets.[63]

Under Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli government proposed closing down the settlement at Tel Rumeida after the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre. Far-right Rabbis moved to block evacuation of the settlements by issuing an Halakhic ruling against removal of settlements in Eretz Israel. The collective influence of the settlers and their Rabbis, in what one scholar has called, 'one of the most effective mobilization efforts in settler history,'[64] persuaded Prime Minister Rabin to back down.[4][51][55][65] The Dir al-Arba'in mosque, where Hebronite Palestinians had prayed until the mid-1990s, was declared a closed military zone, and converted into a synagogue, renamed by settlers Tomb of Ruth and Jesse, and thenceforth all access to it by Muslims was forbidden ostensibly for security reasons.[8] According to Karin Aggestam, attempts to convert the mosque into a Jewish national shrine, including painting its door blue, are in violation of the Hebron Protocol, which committed both Israel and Palestine to preserving and protecting the historic character of the city without harm or changes.[4] During the Al-Aqsa Intifada, the Jewish settlement came under regular fire from Palestinian militants.[66]

In 2005, violence against Palestinians in Hebron most frequently originated with the settlement at Tel Rumeida. The Abu Haikel family is reported to be harassed many times.[67] Of the original 500 Palestinian families resident there, only 50 had remained after what Gideon Levy called a 'reign of terror'.[68][69] Palestinian cars are torched.[70] Long curfews, restrictions on Palestinian movements in the area, and the difficulty of sending children to school like the local Qurtuba (Cordoba) elementary school whose main entrance was sealed with razor wire by the IDF in 2002 and whose students are subject to settler stoning,[71] have, according to one testimony, forced residents in the Palestinian neighbourhood to abandon their homes, and a grocery business and a small hospital to close. Palestinian vehicles are forbidden on Tel Rumeida's streets, and Arab residents can only move in the area on foot.[3] Visits by the International Committee of the Red Cross to check the conditions of Palestinian residents are met by vandalism of vehicles: the flags are stolen, and the emblems on cars damaged since apparently the symbol of the Christian cross is considered 'offensive' to Jewish settlers in the area.[72] B'tselem has a project to provide Palestinians with videos to capture violence against them, and one of the best known videos in the series[73] deals with the harassment Palestinian residents of Tel Rumeida are subject to.[74] According to David Dean Shulman, Palestinian residents have opened a Center for Sumud and Challenge, where the virtue of non-violent resistance and steadfast perseverance (sumud) in the face of harassment is advocated.[75] Situated close to Admot Yishai, the centre, run by Youth Against Settlements (YAS), was subject to an arson attempt in 2013.[63]

A Palestinian resident who refused lucrative offers for her home, has stated that settlers have used home-made napalm to poison their fields, continually burn their cars, and destroy their agricultural tools.[76] In 2011, according to Christian Peacemaker Teams, a further 16 trees from the Haikal's olive groves, some of them reputedly 1,000 years old, were destroyed by fire when settlers set them alight. Palestinian firefighter teams trying to extinguish the flames had their hoses confiscated, and replaced by older ones.[77] Settlers reportedly uprooted roughly 100 olive-tree saplings planted with the help of a Jordanian NGO in the yard of a Palestinian school in Tel Rumeida.[78]

In 2012 an Israeli court ruled that settler claims to have purchased a house in Tel Rumedia in 2005, which had been abandoned by its owner Zechariah Bakri in 2001 when restrictions were imposed on Palestinian movements, were based on forgeries. The house, occupied by 6 settler families, was under a court order requiring them to evacuate it.[79]

At 6 a.m. on the 6th of November, Israeli forces occupied several Palestinian homes and the Beit Sumoud headquarters of the Youth Against Settlements, detaining residents while declaring that their occupation of the dwellings would continue for 24 hours. Palestinian TV crews were reportedly prevented from documenting the incident.[80] Subsequently, the 50 Palestinian families who refuse to leave Tel Rumeida were required to have ID cards permitting them to move in the area: no one else will be permitted to enter the zone.[81] Subsequently, the IDs of Tel Rumeida and Shuhada Street were stamped with numbers, a practice which led to protests by Palestinians who stated 'Israel is the last place in the world that should give people numbers'. The measure, reportedly a local measure, was revoked when higher echelon commanders reviewed the practice.[82]

In late November 2015 Baruch Marzel led a settler assault, demanding the closure of the Beit Sumoud, and engaged in a sit-in occupying its seats, on November 28.[83]

In July 2016 an attempt by local Tel Rumeida Gandhian-style peace activist Issa Amro, and Jawad Abu Aisha, the owner of an old factory to clean up the site and establish infrastructure for a cultural cinema project was blocked by soldiers. Amro had called on Jewish activists to help them, trusting that their presence and privilege would ensure them the few hours require to clear the area and set up a film center. Some 52 mainly diaspora activists, many from religious backgrounds, turned up. Settlers reportedly started tomatoes at them, and the army then detained 15 activists. Subsequently, a military closure was imposed on the site.[84][85]

Fatal incidents

- On 1 July 1995 Ibrahim Khader Idreis (16), while on a visit from Jordan to Tel Rumeida relatives,after stepping outside to buy bread, was shot dead by Baruch Marzel and an IDF soldier. Palestinian residents say he had been ordered to stop by Marzel, and shot in the leg and chest when he didn't. A soldier nearby then shot him in the stomach. The IDF later claimed he had tried to stab the soldier, though no knife was ever produced. Marzel testified that he had acted after the boy threw a stone at him.[86][87]

- On August 21, 1998, Rabbi Shlomo Ra'anan, the grandson of Abraham Isaac Kook and protégé of Zvi Yehuda Kook, was stabbed and killed by a Hamas operative in his trailer home at Tel Rumeida. The attacker then set the house on fire by throwing a Molotov cocktail. The incident determined Binjamin Netanyahu to approve construction in Tel Rumeida, which was premised on preliminary archaeological work. By the time the excavations had been completed, a different Prime Minister, Ehud Barak, was in power and refused to issue the necessary building permits. These were eventually forthcoming after the election of Ariel Sharon in the context of the Al-Aqsa Intifada.[88][89]

- On 21 October 2015, a local resident, physician Hashem al-Azzeh (54) was reportedly denied an ambulance while suffering from cardiac problems. On walking down to the Bab al-Zawiya checkpoint, he was forced to stop and breathed in tear-gas from local clashes, collapsed and died soon afterwards. His wife reportedly had suffered two miscarriages from settler attacks and a 9 year old nephew had had his teeth smashed in by a rock thrown by a settler.[90]

- On 24 March 2016 a resident, shoemaker Imad Abu Shamsiya, was subject to a barrage of abuse and received threats after filming a video of the apparent execution of a wounded Palestinian, who had been shot after stabbing an Israeli soldier, outside his home in Tel Rumeida. An Israeli interrogator reportedly asked him to deny he had filmed the incident, and warned him of the danger he had placed himself among settlers for revealing his identity as the person who filmed the incident.[91][92][93] His house was subject to a night-time raid by Israeli forces to check identity papers after Palestinian and international activists blockaded themselves inside after settlers repertedly threatened to burn it.[94] Itamar Ben-Gvir and Ben-Zion Gopstein later filed a complaint with police against Shamsiya claiming he had coordinated with the terrorists in order to get the incident on film.[95] Elor Azariya, the soldier who executed the wounded Palestinian, testified at his trial that "Hebron is a really tense city. there is always a feeling of tension in the air, especially in Tel Rumeida, which is where there is the most friction between Palestinians and Jews anywhere in the world. It's a stressful place."[96]

Foreign impressions

Nobel Prize winning novelist Mario Vargas Llosa made a tour of Tel Rumeida in 2005, during which he chanced to meet the Israeli journalist Gideon Levy. He recorded his impressions first in the newspaper El Pais,[97] What struck Llosa was the resilience of the 50 Palestinian families, out of 500, who had managed to remain in Tel Rumeida in the face of 'a ferocious, systematic persecution by settlers'. The latter:

throw stones at them, toss rubbish and excrement on their homes; organize raids to invade and devastate their houses, assault their children as the latter return from school while Israeli soldiers look on with total indifference. No one told me about this: I saw it all with my own eyes, heard it with my own ears from the mouths of the victims themselves. I possess a video which shows a hair-raising scene where the boys and girls of the Tel Rumeida settlement hurl stones and kick Arab students and their schoolmistresses at the local Cordoba school, who, to give each other protection, return to their houses in groups, never alone. When I spoke of these facts with my Israeli friends, some stared at me with incredulity and I noted in their eyes the suspicion that I was either exaggerating or lying, as novelists are wont to do. The fact of the matter is that none of them has ever been to Hebron or ever read Gideon Levy’s articles, someone whom they regard indeed as a typical example of the ‘Jew-hating and anti-Semitic’ Jew.[98]

The American Jewish writer Peter Beinart described one joint Jewish-Palestinian attempt to create a small cinema on an abandoned Palestinian factory in Tel Rumeida. The venture was quickly blocked by an IDF order declaring the site a closed military zone and by the detention of several Jewish activists. Beinart drew an analogy between the work of the local activist Issa Amro and Robert Parris Moses, likening their effort to that of American activists against racial segregation in Mississippi in 1964. He added that:

Why were we performing Kabbalat Shabbat? I can’t speak for everyone, but for me, it was partly to remind myself of who I am. I had spent the day working alongside Palestinians and being protected by them. I had spent the day fearing Jewish soldiers and police. It was a jarring experience. The normal order of things, as I had learned them since childhood, had been turned upside down. Welcoming Shabbat was a way of centering myself. It was a reminder that no matter how many people tell me I hate Judaism, the Jewish people and the Jewish state — no matter how many people tell me I hate myself — I know who I am. I know when I’m living in truth. And nothing feels more Jewish than that.[85]

Beinart announced his intention of getting 500 Jews to join him in at the same area in 2017 to protest the 50th anniversary of the Israeli Occupation of the West Bank.[85]

Notable residents

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tel Rumeida. |

- ↑ Raja Shehadeh, From Occupation to Interim Accords: Israel And the Palestinian Territories, BRILL 1997 p.289.

- ↑ Michael Dumper; Bruce Stanley (2006). Cities of The Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 167. ISBN 978-1576079195.

- 1 2 'Ghost Town:Israel’s Separation Policy and Forced Eviction of Palestinians from the Center of Hebron,' B'tselem May 2007 pp.15,19-20,23,25

- 1 2 3 Karin Aggestam (2005). "4. TIPH: Preventing Conflict Escalation in Hebron?". In Clive Jones; Ami Pedahzur. Between Terrorism and Civil War: The Al-Aqsa Intifada. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 0415348242.

- ↑ "The Geneva Convention". BBC News. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ Detlef Jericke, Abraham in Mamre: Historische und exegetische Studien zur Region von Hebron und zu Genesis 11, 27–19,38, BRILL 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 Claude Reignier Conder, Herbert Kitchener,The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London, 1883, Vol 3 pp.327-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Yonathan Mizrachi, 'Tel Rumeida Hebron’s Archaeological Park,' Emek Shaveh November 2014

- 1 2 Kenneth Anderson Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003 p.184

- 1 2 3 4 5 Denys Pringle,The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus: Volume 2, L-Z, Cambridge University Press, 1998 pp.203-204.

- 1 2 K. Van Bekkum, From Conquest to Coexistence: Ideology and Antiquarian Intent in the Historiography of Israel’s Settlement in Canaan, BRILL 2011 pp.520-524, sums up the results given in Hammond's student, Jeffrey Chadwick, in his 1992 doctoral dissertation.J.R. Chadwick, The Archaeology of Biblical Hebron in the Bronze and Iron Ages: An Examination of the Discoveries of the American Expedition to Hebron, University of Utah 1992. The work is criticized as subpar by Jericke,pp. 20-21

- ↑ Yifa Yaakov, 'State funding archaeological dig in heart of Hebron,' The Times of Israel 9 January 2014.

- ↑ Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation, Verso Books, 2012 p.275 n.37.

- 1 2 Megan Hanna, http://www.maannews.com/Content.aspx?id=769069 'The dark role of archeology in the battle for Hebron's Tel Rumeida,' Ma'an News Agency 29 November 2015.

- 1 2 Herzog, Ze'ev; Singer-Avitz, Lily (September 2004). "Redefining the Centre: The Emergence of State in Judah" (PDF). Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. Maney Publishing. 31 (2): 219–220.

- ↑ Jericke, p. 21

- ↑ Jericke, 21-22.

- ↑ Richard S. Hess, Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey, Baker Academic, 2007 p.136

- 1 2 Jericke, p.24,

- ↑ Jericke, p.25

- ↑ Jericke, p.27.

- ↑ Thomas L. Thompson, Biblical Narrative and Palestine's History: Changing Perspectives 2, Routledge 2014 p.335.

- 1 2 Nir Hasson, 'Israeli Government Funding Dig in Palestinian Hebron, Near Jewish Enclave,' Haaretz 9 January 2014

- ↑ 'Update: The Archaeological Excavations in Tel Rumeida, Hebron,' Emek Shaveh, April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Moshe Sharon, Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Vol 5, H-I BRILL, 2013 pp.45-52.

- ↑ Lior Lehrs, 'Political holiness: negotiating holy places in Eretz Israel/Palestine, 1937-2003,' in Marshall J. Breger, Yitzhak Reiter, Leonard Hammer (eds.),Sacred Space in Israel and Palestine: Religion and Politics, Routledge, 2013 pp.228-249 p.242.

- 1 2 Franciscus Quaresmius, Historica theologica et moralis Terrae Sanctae, 1639, vol 2 p.782.

- ↑ Juan Perera, A Spanish Franciscan's Narrative of a Journey to the Holy Land, edited by H. C. Luke London, 1927, cited Pringle p.203.

- ↑ Frederick M. Strickert , Rachel Weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb, Liturgical Press, 2007 p.141.

- ↑ Ora Limor, ‘Sharing Sacred Space: Holy Places in Jerusalem Between Christianity, Judaism, and Islam’ in Iris Shagrir, Roni Ellenblum, Jonathan Simon Christopher Riley-Smith (eds.), Laudem Hierosolymitani, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2007 pp.219-231 p.224.

- ↑ Elkan Nathan Adler, Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages: 19 Firsthand Accounts, Courier Corporation, 1930 reprint pp.115.129 p.120.

- ↑ Adler, p.187.

- ↑ Moses ben Mordecai Basola, 'In Zion and Jerusalem: the itinerary of Rabbi Moses Basola (1521-1523),' C. G. Foundation Jerusalem Project Publications of the Martin (Szusz) Department of Land of Israel Studies of Bar-Ilan University, 1999 p.77. at the summit of the mountain opposite Hebron is the burial place of Jesse, David's father. It has a handsome building with a small window that looks down on the burial cave. They say that once they threw a cat through the window and it emerged from the hole in the Cave of the Patriarchs. The distance between them is half a mile."

- ↑ Professor Miller, 'Description of Minerals from Palestine,' in The American Journal of Science and Arts S. Converse, 1825 p.343.

- ↑ Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Lectures on the History of the Jewish Church,, 5th ed. C. Scribner, 1870 Vol. 1 p.548.

- ↑ Lady Judith Montefiore writing of a visit in 1827-1826 recorded that,"while the fete was being prepared, we rode up the hill to visit some ancient tombs, one of which was that of Jesse, the father of David, and at which we said our evening prayers, joined by eight Israelites who had accompanied us."Lady Judith Montefiore,Notes from a Private Journal of a Visit to Egypt and Palestine: By Way of Italy and the Mediterranean, J. Rickerby, 1844 p.310.

- ↑ John D Paxton wrote:'While rambling among the olive-trees that almost cover the hill to the south-west of the town, we came to the ruins of an old building, which must have been a place of some consequence formerly, but is now wholly deserted. Our guide took us into it, and in one of the rooms showed us a small hole in the wall, which he told us was the tomb of Jesse, the father of David. The Jews, who were with us, certainly showed much reverence for the place. .Whether this be the grave of Jesse none can tell, nor is it worth much inquiry.'John D. Paxton, Letters from Palestine, Charles Tilt, 1839 p.143.

- ↑ David Millard wrote:"On a hill to the north-west of the town, we were conducted to what are shown as the tombs of Jesse and Abner. They were both rude stone buildings, going in decay, and contained nothing of interest. Having very little faith in the identity of these, I shall attempt no description of them.' David Millard, A Journal of Travels in Egypt, Arabia Petræ, and the Holy Land: During 1841-2, E. Shepard, 1843 p.239.

- ↑ ‘Travels in the Holy Land’ in The Sunday at Home: A Family Magazine for Sabbath Reading, Religious Tract Society Vol. 8 1861 pp.112-117, p.116.

- ↑ Haaretz Editorial, 'Hebron Dig: Annexation in the Guise of Archaeology,' Haaretz10 January 2014

- ↑ Hanne Eggen Røislien, 'Living with Contradiction: Examining the Worldview of the Jewish Settlers in Hebron,' IJCV, Vol.1 (2) 2007, pp.169–184.

- 1 2 Marshall J. Breger,Yitzhak Reiter,Leonard Hammer (eds.), Sacred Space in Israel and Palestine: Religion and Politics, Routledge, 2013 p.479

- 1 2 Edward Platt, City of Abraham: History, Myth and Memory: A Journey through Hebron, Pan Macmillan 2012 pp.79ff.p.129

- ↑ A. Nir, N.Shragai, 'IDF Removes Torah Scroll Placed BY Settlers in Jesse's Tomb,' Haaretz (Hebrew) 22 November 1995

- ↑ Rebecca Anna Sotil, 'Vandals damage Jesse's Tomb in Hebron,' Jerusalem Post 30 January 2007.

- ↑ Tovah Lazaroff, 'Converts pay homage to Ruth at her Hebron tomb,' Jerusalem Post 18 May 2010.

- ↑ Michelle Campos, 'Remembering Jewish-Arab Contact and Conflict,' in Mark LeVine (ed.),Reapproaching Borders: New Perspectives on the Study of Israel-Palestine, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007 pp.41-66, p.41.

- ↑ Chaim Levinsohn, 'Israel Supreme Court Rules Hebron Jews Can't Reclaim Lands Lost After 1948 ,' Haaretz 18 February 2011.

- 1 2 'Israelis begin construction on new settlement in central Hebron,' Ma'an News Agency 5 January 2014.

- ↑ Kathleen Kern, As Resident Aliens: Christian Peacemaker Teams in the West Bank, 1995-2005, Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2010 pp.25ff.

- 1 2 OCCUPATION IN HEBRON, OCHA March 2004, pp.12,18-19.

- ↑ 'Jungle law' in Hebron, Gulf Daily News, Bahrain 19 May 2006:'Abu Haikal's grandfather ran a grocery shop with a Jewish partner and lit the homes of Jewish neighbours on the Sabbath, which under Jewish law is considered work. During the 1929 riots, he personally shielded Jews from death."I used to ask my father why did you protect them? He told me we lived with the Jews and looked after each other as humans," says Hani, unable to quite understand how it could have changed in a generation.'

- 1 2 3 Aryeh Dayan 'Two Tales of One City,' Haaretz 18 January 2007:'At the beginning of the 1980s, he relates, Dr. Yosef Burg, who was then interior minister, and whose wife was born in Hebron, visited the town. According to Abu Aisha, Burg "told the settlers that they must not harm the Abu Aisha family, because everyone knows that members of the family saved Jews. But Burg departed and left us with Baruch Marzel.’

- ↑ "Ehud Sprinzak, 62; Studied Israel Far Right". The New York Times. 12 November 2002.

- 1 2 3 Ehud Sprinzak, 'Israel's Radical Right and the Countdown to Rabin's Assassination,' in Yoram Peri (ed.), The Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, Stanford University Press 2000 pp.104f.

- ↑ Auerbach p.129

- ↑ Elliott S. Horowitz, Reckless Rites: Purim and the Legacy of Jewish Violence, Princeton University Press, 2006 p.7.

- ↑ Raphael Ahren,'The extremist who could bring Kahanism back to the Knesset,' The Times of Israel 16 February 2015.

- ↑ 'Daily attacks by settlers on the Abu 'Aisha family, Tel Rumeida, Hebron,’ B'tselem 2007,

- ↑ Michaela Whitton, 'Growing up in the massacre's shadow: Children of Hebron,' Middle East Eye 3 March 2015.

- ↑ Bethan Staton, 'The Palestinian struggle to remain in Hebron,' Middle East Eye 1 March 2015

- ↑ Bill Baldwin, Samah Sabawi,The Journey to Peace in Palestine: From the Song of Deborah to the Simpsons, Dorrance Publishing, 2010 pp.19ff.

- 1 2 Marion Lecoquierre, 'Bienvenue à Hébronland,' Le monde diplomatique 10 December 2013.

- ↑ Ehud Sprinzak, 'The Israeli Right and the Peace Process,' in Sasson Sofer (ed.) Peacemaking in a Divided Society: Israel After Rabin, Frank Cass 2001 pp67-96, pp77-79,p.78.

- ↑ Idith Zertal, Akiva Eldar, Lords of the Land: The War Over Israel's Settlements in the Occupied Territories, 1967-2007, Nation Books, 2014 pp.124,296

- ↑ Boukaert,Center of the Storm, p.63

- ↑ Kathleen Kern, 'As Resident Aliens: Christian Peacemaker Teams in the West Bank, 1995-2005,' Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2010 pp.25f.n.18, pp.247-8

- ↑ Gideon Levy, 'Twilight Zone Mean Streets ,' Haaretz 8 September 2005:'About 500 Palestinian families once lived here; now barely 50 are left. What is going on here, far from the public eye, isn't just a cruel 'transfer,' but a reign of terror imposed by the settlers on the handful of residents who haven't left yet. This is where they built a settler stronghold that grew to frightening proportions, a multi-story building constructed with state sponsorship, surrounded now by a virtual ghost town, save for the small group of residents still clinging to their homes despite all the horror visited upon them by these violent lords of the land, these unwanted neighbors.'

- ↑ Platt, City of Abraham, p.12.

- ↑ Ali Waked,'Palestinians: Settlers torched our cars,' Ynet 7 May 2006.

- ↑ Saree Makdisi, Palestine Inside Out: An Everyday Occupation, W. W. Norton & Company, 2010 pp.209-10

- ↑ Peter Bouckaert, Center of the Storm: A Case Study of Human Rights Abuses in Hebron District, Human Rights Watch 2001 pp.86,197.

- ↑ Saree Makdisi, Palestine Inside Out pp.137-138:'The Palestinian family was obliged to build a wire cage to protect the home's doors and windows. The video shows a Palestinian mother anxiously waiting for the return of her kids from school. . .settler boys playing in the street start peltin g her with stones (A soldier tries to stop them) . . A settler woman approaches the cage door and pushes it open. The Palestinian woman starts screaming at her, telling her to back away. The soldier looks on helplessly. The Jewish woman withdraws, but puts her face up to the wire of the cage and, cuppin g her hands, moans out softly, with her Hebrew-accented Arabic, Shaghmouta . . Shaghmouta. (Sharmouta is "whore" in Arabic). The Palestinian woman has to face this kind of abuse every time she steps outside the door of her home.'

- ↑ Alisa LeBow,'Shooting with Intent: Framing Conflict,' in Joram ten Brink,Joshua Oppenheimer (eds., Killer Images: Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of Violence, WallFlower Press/Colum bia University Press 2012 pp.41-61 p.53.

- ↑ David Dean Shulman, 'Hope in Hebron,' The New York Review of Books, 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Michael McRay, Letters from "Apartheid Street": A Christian Peacemaker in Occupied Palestine, Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2013 p.26.

- ↑ 'CPT: Settlers torch Palestinian olive grove,' Ma'an News Agency 28 May 2011

- ↑ Protection of Civilians: Reporting Period 24 February- 2 March,2015,UNISPAL/OCHA 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Chaim Levinson, 'Israeli Court Orders Eviction of Settlers From Another Hebron House,' Haaretz 22 April 2012.

- ↑ 'Israeli forces storm homes, activist center in Hebron,' Ma'an News Agency 7/8 November 2025.

- ↑ Jonathan Cook,'Smart Resistance: a Palestinian Call for ‘Unarmed Warfare’,' CounterPunch 12 November 2015

- ↑ Elior Levy, 'IDF assignation of numbers to Palestinians sparks outcry,' Ynet, 5 January 2016.

- ↑ 'Israeli settlers storm Palestinian activist center in Hebron,' Ma'an News Agency 28 November 2015.

- ↑ 'Israeli forces detain at least 15 activists in the Tel Rumeida area of Hebron,' Ma'an News Agency 15 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Peter Beinart, 'What I Saw Last Friday in Hebron,' Haaretz 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Kathleen Kern, In Harm's Way: A History of Christian Peacemaker Teams, Lutterworth Press, 2014 p.104

- ↑ Khalid Amayreh, Zionists aim for ethnically pure Palestine,' Al Jazeera 18 September 2003.

- ↑ Mannes, Aaron (2004). Profiles in terror : the guide to Middle East terrorist organizations. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 9780742535251.

- ↑ Jerold S. Auerbach, Hebron Jews: Memory and Conflict in the Land of Israel, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009 p.147.

- ↑ Killian Redden, 'After years of peaceful protest, Hebron doctor dies in tear gas,' Ma'an News Agency 22 October 2015

- ↑ 'Israeli settlers threaten Palestinian who filmed Hebron 'execution',' Ma'an News Agency 25 March 2016.

- ↑ 'Israel/Palestine: Summary Execution of Wounded Palestinian:Rights Worker Who Filmed Killing Threatened,' Human Rights Watch 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Philip Weiss,'Video: Meet the brave shoemaker who filmed Israeli soldier executing a Palestinian,' Mondoweiss 28 March 2016.

- ↑ 'Israeli Forces Storm House of Palestinian who Captured Hebron Killing Footage,' Wafa 30 March 2016.

- ↑ Dan Cohen, 'Hebron settlers file complaint against Palestinian who filmed execution,' Mondoweiss 27 March 2016.

- ↑ Yossi Yehoshua, Yoav Zitun,'Azaria's testimony: 'you can't walk through Hebron like you can Tel Aviv. There's always fear,' Ynet 24 July 2016.

- ↑ Mario Vargas Llosa, 'Paz o guerra santa,' El Pais 10 February 2005

- ↑ Mario Vargas Llosa, Israel, Santillana USA, 2006 (orig.Israel/Palestina.Paz o guerra santa, Santillana Lima) p.68:’Y sólo en el barrio de Tel Rumeida, donde está el asentamiento de este nombre, de las 500 familias árabes que allí residían quedan apenas 50. Lo extraordinario es que éstas no se hayan marchado todavía, sometidas como están a un acoso sistemático y feroz de parte de los colonos, que las apedrean, arrojan basuras y excrementos a sus casas, montan expediciones para invadir sus viviendas y destrozarlas, y atacan a sus niños cuando regresan de la escuela, ante la absoluta indiferencia de los soldados israelíes que presencian estas atrocidades. Nadie me lo ha contado: yo lo he visto con mis propios ojos y lo he oído con mis propios oídos de boca de las mismas víctimas. Y tengo en mi poder un vídeo donde se ve la espeluznante escena de niños y niñas del asentamiento de Tel Rumeida apedreando y pateando a los escolares árabes y sus maestras de la escuela "Córdoba" (Qurtaba) del barrio, quienes, para protegerse unos a otros, regresan a sus hogares en grupo en vez de hacerlo de manera individual. Cuando comenté esto con amigos israelíes, algunos me miraron con incredulidad y vi en sus ojos la sospecha de que yo exageraba o mentía, como suelen hacer los novelistas. Ocurre que ninguno de ellos pisa jamás Hebrón ni tampoco lee a Gideon Levy, a quien consideran el típico judío "judeófobo y antisemita".’

Coordinates: 31°31′26″N 35°06′14″E / 31.524°N 35.104°E