Swissair Flight 111

.jpg) HB-IWF, the aircraft involved in the accident, seen at Zurich Airport in July 1998, two months before the crash. | |

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | 2 September 1998 |

| Summary | In-flight fire, leading to electrical and instrument failure, causing spatial disorientation and loss of control; impacted ocean[1]:253–254 |

| Site | Atlantic Ocean, near St. Margarets Bay, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Passengers | 215 |

| Crew | 14 |

| Fatalities | 229 (all) |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Aircraft type | McDonnell Douglas MD-11 |

| Aircraft name | Vaud |

| Operator | Swissair |

| Registration | HB-IWF |

| Flight origin |

John F. Kennedy Int'l Airport New York City, United States |

| Destination |

Cointrin International Airport Geneva, Switzerland |

Swissair Flight 111 (ICAO: SR111, SWR111) was a scheduled international passenger flight from New York City, United States, to Geneva, Switzerland. This flight was also a codeshare flight with Delta Air Lines. On 2 September 1998, the McDonnell Douglas MD-11 performing this flight, registration HB-IWF, crashed into the Atlantic Ocean southwest of Halifax International Airport at the entrance to St. Margarets Bay, Nova Scotia. The crash site was 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) from shore, roughly equidistant from the tiny fishing and tourist communities of Peggys Cove and Bayswater. All 229 passengers and crew aboard the MD-11 died—the highest death toll of any McDonnell Douglas MD-11 accident in aviation history,[2] and the second-highest of any air disaster to occur in Canada, after Arrow Air Flight 1285, which crashed in 1985 with 256 fatalities. This is one of the three MD-11 accidents with passenger fatalities along with China Eastern Airlines Flight 583 and another hull loss of China Airlines Flight 642.

The search and rescue response, crash recovery operation, and investigation by the Government of Canada took over four years and cost CAD 57 million (at that time approximately US$38 million).[3] The Transportation Safety Board of Canada's (TSB) report of their investigation stated that flammable material used in the aircraft's structure allowed a fire to spread beyond the control of the crew, resulting in a loss of control and the crash of the aircraft.[1]:253

Swissair Flight 111 was known as the "UN shuttle" because of its popularity with United Nations officials; the flight also carried business executives, scientists, and researchers.[4]

Involved

Aircraft

The aircraft, a McDonnell Douglas MD-11, serial number 48448, registration HB-IWF, was manufactured in 1991 and Swissair was its only operator. It bore the title of Vaud, in honor of the Swiss canton of the same name. The cabin was configured with 241 seats. First- and business-class seats were equipped with in-seat in-flight entertainment system. The aircraft was powered by three Pratt & Whitney 4462 turbofan engines and had logged a total of 36,041 hours before the crash.[1]:9

Crew

The pilot-in-command was 49-year-old Urs Zimmermann. At the time of the accident, he had approximately 10,800 hours of total flying time, of which 900 hours were in an MD-11. He was also an instructor pilot for the MD-11. Before his career with Swissair, he was a fighter pilot in the Swiss Air Force. Zimmermann was described as a friendly person with professional skills, who always worked with exactness and precision.[1]:5–7

The first officer, 36-year-old Stefan Löw, had approximately 4,800 hours of total flying time, including 230 hours in MD-11. He was an instructor on the MD-80 and A320. From 1982 to 1990, he had been a pilot in the Swiss Air Force.[1]:6 The cabin crew comprised a maître de cabine (purser) and eleven flight attendants. All crew members on board Swissair Flight 111 were qualified, certified, and trained in accordance with Swiss regulations under the Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA).

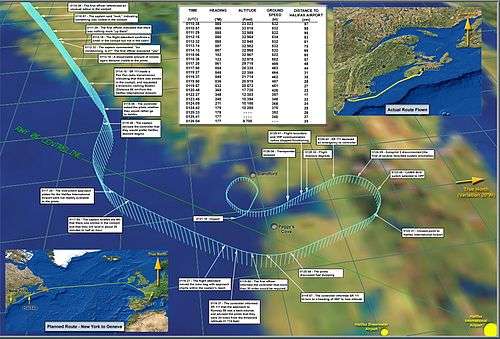

Flight timeline

The flight took off from New York's John F. Kennedy Airport at 20:18 Eastern Daylight Time (00:18 UTC). From 20:33 EDT (00:33 UTC) until 20:47 EDT (00:47 UTC), the aircraft experienced an unexplained thirteen-minute radio blackout, of which cause was determined to be communication radios tuning errors.[5]

At 22:10 Atlantic Time (01:10 UTC), the flight crew detected an odour in the cockpit and determined it to be smoke from the air conditioning system. Following the captain's request, the crew turned off the air conditioning vent. Four minutes later, the odour returned and the smoke became visible, prompting the pilots to make a "pan-pan" radio call to the air traffic control Moncton. ATC Moncton controls air traffic over the Province of Nova Scotia, including most flights en route to or from Europe. The pan-pan call indicated that there was an urgency due to smoke in the cockpit but did not declare an emergency as denoted by a "Mayday" call. The crew requested a diversion to a convenient airport. They then accepted ATC Moncton's offer of a vector to the closer Halifax International Airport in Enfield, Nova Scotia, 66 nm (104 km) away rather than Logan International Airport, Boston, which at that time was 234 nautical miles (433 km) further away.[1]:01

At 22:18 AT (01:18 UTC), ATC Moncton handed over traffic control of the plane to Halifax Terminal Control Unit, a specialized ATC unit managing traffic in and out of Halifax.

At 22:19 AT (01:19 UTC), the crew requested more distance for the aircraft to descend from 21,000 feet (6,400 m) when they were advised the aircraft was 30 nautical miles (56 km) away from Halifax International Airport.

At 22:20 AT (01:20 UTC), on the crew's fuel dump request, ATC Halifax diverted the plane toward St. Margaret's Bay, where it was safer for the aircraft to dump fuel and still in the distance of 30 nautical miles (56 km) from Halifax.[1]:01

In accordance with the Swissair checklist entitled "In case of smoke of unknown origin", the crew shut off the power supply in the cabin, which also turned off the recirculating fans in the ceiling. This created a vacuum in the ceiling space above the passenger cabin and induced the fire to spread into the cockpit, cutting off the power of autopilot. At 22:24:28 AT (01:24:28 UTC), the crew informed ATC Halifax that "we now must fly manually", followed by two times of emergency declarations. Ten seconds later, the crew declared emergency the third time "And we are declaring emergency now Swissair one eleven", which were the last words received from Flight 111.[6] The flight data recorder stopped recording at 22:25:40 AT (01:25:40 UTC), followed one second later by the cockpit voice recorder. The aircraft briefly appeared again on radar screens from 22:25:50 AT (01:25:50 UTC) to 22:26:04 AT (01:26:04 UTC). The last altitude recorded was 9,700 feet. According to the cockpit voice recorder, shortly after the first emergency declaration, the captain left his seat to fight the fire that was spreading to the rear of the cockpit; the Swissair volume of checklists was later found fused together in the wreckage, indicating that the captain may have attempted to use them to fan back the flames.[5] The captain did not return to his seat; whether he was killed by the fire, asphyxiated by the smoke, or killed in the crash is not known. Flight data recording shows that engine two was shut down due to an engine fire approximately one minute before impact,[5] implying that the first officer was still alive and continued trying to take back control of the aircraft until the final moments of the flight. At 22:31:18 AT (01:31:18 UTC), the aircraft struck the ocean at an estimated speed of 345 mph (555 km/h, 154 m/s, or 299 knots) and with a force of the order of 350 g, causing the aircraft to disintegrate instantly.[1]:116 The crash location was approximately 44°24′33″N 63°58′25″W / 44.40917°N 63.97361°WCoordinates: 44°24′33″N 63°58′25″W / 44.40917°N 63.97361°W, with 300 meters' uncertainty.[7]

Post-crash response

Search and rescue operation

The search and rescue (SAR) operation was code-named Operation Persistence and was launched immediately by Joint Rescue Coordination Centre Halifax (JRCC Halifax), which tasked the Canadian Forces Air Command, Maritime Command, Land Force Command, Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) and Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary (CCGA) resources.

The first rescue resources to approach the crash site were CCGA volunteer units. These units were mostly privately owned fishing boats that operated out of Peggys Cove, Bayswater, and other harbours on St. Margaret's Bay and the Aspotogan Peninsula. They were soon joined by the dedicated Canadian Coast Guard SAR vessel CCGS Sambro and CH-113 Labrador SAR helicopters flown by the 413 Squadron from CFB Greenwood.

The crash site's proximity to Halifax meant that ships docked at Canada's largest naval base, CFB Halifax, and one of the largest Canadian Coast Guard bases, CCG Base Dartmouth, were within one hour's sailing time. Calls immediately went out and ships sailed as soon as possible to St. Margaret's Bay.[8]

The land-based search, including shoreline searching, was the responsibility of Halifax Regional Search and Rescue. The organization was responsible for all ground operations including military operations and other ground search and rescue teams.[9]

| List of vessels involved in the searching and rescue actions | |

|---|---|

The following are ships that took part in the search and rescue operation after the accident.

| |

Search and recovery operation

By the afternoon of 3 September, it was apparent that there were no survivors from the crash and JRCC Halifax de-tasked dedicated SAR assets (CCGS Sambro and the CH-113 Labrador helicopters). The Royal Canadian Mounted Police were given overall command of the recovery operation, with HMCS Preserver (AOR 510) remaining on-scene commander.

The aircraft broke up on impact with the water and most of the debris sank to the ocean floor (a depth of 55 m (180 ft)). Some debris was found floating in the crash area and over the following weeks debris washed up on the nearby shorelines.[1]:77

The initial focus of the recovery was on finding and identifying human remains and on recovering the flight recorders. As the force of impact was "in the order of at least 350 g",[1]:104 the aircraft was fragmented and the environmental conditions only allowed the recovery of human remains along with the aircraft wreckage.[1]:103–105 Only one of the victims was visually identifiable. Eventually, 147 were identified by fingerprint, dental records, and X-ray comparisons. The remaining 81 were identified through DNA tests.[11]:264

With Canadian Forces divers (navy clearance divers, port inspection divers, ship's team divers, and Army combat divers) working on the recovery, a request was made by the Government of Canada to the Government of the United States for a larger dedicated salvage recovery vessel. USS Grapple was tasked to the recovery effort, arriving from Philadelphia on 9 September. Among Grapple's crew were 32 salvage divers.[12][13]

The cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and flight data recorder (FDR) were found by the submarine HMCS Okanagan using sonar to detect the underwater locator beacon signals and were quickly retrieved by Canadian Navy divers (the FDR on 6 September and the CVR on 11 September 1998). Both had stopped recording when the aircraft lost electrical power at approximately 10,000 ft (3,000 m), 5 minutes and 37 seconds before impact.[1]:74

The recovery operation was guided by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) with resources from the Canadian Forces, Canadian Coast Guard, RCMP, and other agencies. The area was surveyed using route survey sonar, laser line scanners, and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to locate items. After being located, the debris was then recovered (initially by divers and ROVs, later by dredging and trawling).[14]

On 2 October 1998, the TSB initiated a heavy lift operation to retrieve the major portion of the wreckage from the deep water before the expected winter storms began. By 21 October, an estimated 27% of the wreckage was recovered.[15]

At that point in the investigation, the crash was generally believed to have been caused by faulty wiring in the cockpit after the entertainment system started to overheat. Certain groups issued Aviation Safety Recommendations. The TSB released its preliminary report on 30 August 2000 and the final report in 2003.[1]:298

The final phase of wreckage recovery employed the ship Queen of the Netherlands to dredge the remaining aircraft debris. It concluded in December 1999 with 98% of the aircraft retrieved: approximately 279,000 lb (127,000 kg) of aircraft debris and 40,000 lb (18,000 kg) of cargo.[1]:77

Response to victims' families and friends

JFK Airport used the JFK Ramada Plaza to house relatives and friends of the victims of the crash, due to the hotel's central location relative to the airport.[16] Jerome "Jerry" Hauer, the head of the emergency management task force of Mayor of New York City Rudy Giuliani, praised the response of Swissair and codeshare partner Delta Air Lines in responding to the accident; he had criticized Trans World Airlines in its response to the TWA Flight 800 crash in 1996.[17]

Investigation

Examination

An estimated 2 million pieces of debris were recovered and brought ashore for inspection at a secure handling facility in a marine industrial park at Sheet Harbour, where small material was hand inspected by teams of RCMP officers looking for human remains, personal effects, and valuables from the aircraft's cargo hold. The material was then transported to CFB Shearwater, where it was assembled and inspected by over 350 investigators from multiple organizations, such as the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, U.S. National Transportation Safety Board, U.S. Federal Aviation Authority (FAA), Air Accidents Investigation Branch, Boeing, Pratt & Whitney, and Swissair.[1]:80[18]

As each piece of wreckage was brought in, it was carefully cleaned with fresh water, sorted, and weighed. The item was then placed in a specific area of a hangar at CFB Shearwater, based on a grid system representing the various sections of the plane. All items not considered significant to the crash were stored with similar items in large boxes. When a box was full, it was weighed and moved to a custom-built temporary structure (J-Hangar) on a discontinued runway for long-term storage. If deemed significant to the investigation, the item was documented, photographed, and kept in the active examination hangar.[1]:197–198 Particular attention was paid to any item showing heat damage, burns, or other unusual marks.

The lack of flight recorder data for the last six minutes of the flight added significant complexity to the investigation and was a major factor in its lengthy duration. The Transportation Safety Board team had to reconstruct the last six minutes of flight entirely from the physical evidence. As the aircraft was broken into 2 million pieces by the impact, this process was time-consuming and tedious. The investigation became the largest and most expensive transport accident investigation in Canadian history, costing C$57 million (US$48.5 million) over five years.[19]

Cockpit and recordings

The front 33 ft (10 m) of the aircraft, from the front of the cockpit to near the front of the first-class passenger cabin, was reconstructed. Information gained by this allowed investigators to determine the severity and limits of the fire damage, its possible origins, and progression.[1]:199 The cockpit voice recorder used a 1/4 inch recording tape that operated on a 30-minute loop. It therefore only retained that half-hour of the flight before the recorders failed, six minutes before the crash.[1]:73–74 The CVR recording and transcript were covered by a strict privilege under section 28 of the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act[20] and thus were not publicly disclosed. The air traffic control recordings are less strictly privileged: section 29 of the same act provides only that they may not be used in certain legal proceedings.[21] The air traffic control transcripts were released within days of the crash in 1998[22] and the air traffic control audio was released in May 2007.[23]

Probable cause

The TSB investigation identified eleven causes and contributing factors of the crash in its final report. The first and most important was:

Aircraft certification standards for material flammability were inadequate in that they allowed the use of materials that could be ignited and sustain or propagate fire. Consequently, flammable material propagated a fire that started above the ceiling on the right side of the cockpit near the cockpit rear wall. The fire spread and intensified rapidly to the extent that it degraded aircraft systems and the cockpit environment, and ultimately led to the loss of control of the aircraft.[1]:253

Investigators identified evidence of arcing in wiring of the in-flight entertainment system network, but this did not trip the circuit breakers. The investigation was unable to confirm if this arc was the "lead event" that ignited the flammable covering on MPET insulation blankets that quickly spread across other flammable materials.[1]:253 The crew did not recognize that a fire had started and were not warned by instruments. Once they became aware of the fire, the uncertainty of the problem made it difficult to address. The rapid spread of the fire led to the failure of key display systems, and the crew were soon rendered unable to control the aircraft. Because he had no light by which to see his controls after the displays failed, the pilot was forced to steer the plane blindly; intentionally or not, the plane swerved off course and headed back out into the Atlantic. Recovered fragments of the plane show that the heat inside the cockpit became so great that the ceiling started to melt. The recovered standby attitude indicator and airspeed indicators showed that the aircraft struck the water at 300 knots (560 km/h, 348 mph) in a 20 degrees nose down and 110-degree bank attitude, or almost inverted; the impact force of the aircraft crashing into the Atlantic Ocean was later calculated to be 350 times the force of gravity ("G"s).[1]:103[24] Death was instantaneous for all passengers and crew due to the impact forces and deceleration.[1]:104

The TSB concluded that even if the crew had been aware of the nature of the problem immediately after detection of the initial odor, and had commenced an approach as rapidly as possible, the developing fire-related conditions in the cockpit would have made a safe landing at Halifax impossible.[1]:246,257

TSB recommendations

The TSB made nine recommendations relating to changes in aircraft materials (testing, certification, inspection, and maintenance), electrical systems, and flight data capture, as both flight recorders had stopped when they lost power six minutes before impact. General recommendations were also made regarding improvements in checklists and in fire-detection and fire-fighting equipment and training. These recommendations have led to widespread changes in FAA standards, principally impacting wiring and fire hardening.

2011 speculation

In September 2011, the CBC program The Fifth Estate reported allegations suggesting that an incendiary device might have been the cause of the crash. These claims came from a former RCMP arson investigator who was assigned to the Swissair file the day after the crash. Sgt. Tom Juby claimed that suspicious levels of magnesium and other elements associated with arson were discovered in the wiring and that he was ordered to remove references to magnesium or a suspected bomb from his investigative notes.[25] The TSB claimed that the high levels of magnesium in some wires could be explained by prolonged exposure to sea water during the recovery effort. A TSB document obtained by the Fifth Estate showed that the TSB had placed pristine wires in sea water for several weeks and upon testing those wires showed no traces of magnesium.

Victims

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 41 | 0 | 41 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 31 | 13 | 44 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 110 | 1 | 111 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 215 | 14 | 229 |

Most of the passengers were American, French, or Swiss.[5][26]

There were 132 American (including one Delta Air Lines flight attendant and one United Air Lines flight attendant), 41 Swiss (including the 13 crew members), 30 French, six British, three German, three Italian, three Canadian, two Greek, two Lebanese, one each from Afghanistan, China, India, Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, St. Kitts and Nevis, Sweden, and Yugoslavia, and four other passengers on board.[27][28]

Notable victims

Several notable individuals died in this accident, including:

- Pierre Babolat, head of Babolat.[29]

- Roger R. Williams, MD, an accomplished and internationally recognized cardiovascular geneticist and professor of internal medicine, and the founder of the Cardiovascular Genetics research clinic at the University of Utah, was traveling from New York to Geneva where he was to chair a MEDPED meeting at the World Health Organization.[30][31]

- Pierce J. Gerety, Jr., UNHCR Director of Operations for the Great Lakes Region of Africa, who was on a special mission for U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to attempt to negotiate a peace accord with Laurent Kabila in an erupting regional war.

- Klaus Kinder-Geiger, who specialized in the theory of BNL's Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC).[32]

- Joseph LaMotta, son of former boxing world champion Jake LaMotta.

- Jonathan Mann, former head of the WHO's AIDS program, and his wife, AIDS researcher Mary Lou Clements-Mann.

- Prof. Victor Rizza, professor of Pharmacology, University of Catania, Italy.[33]

- Per Spanne, a physicist from the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) who had been working at Brookhaven National Laboratory since 1996.[32]

- Mahmood Diba, the cousin of Empress Farah of Iran

- John Mortimer, a former New York Times executive and his wife Hilda

- Bandar Bin Saud bin Saad Abdul Rahman al-Saud, a Saudi royal Prince

- Stephanie Shaw, daughter of Geneva-based Scottish entrepreneur, Ian Shaw

Identification

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) medical examiners identified most of the bodies within 10 weeks of the accident. Due to extreme impact forces only one body was identifiable by sight. For approximately 100 bodies, the examiners used DNA; the DNA analysis has been referred to as the largest DNA identification project in Canadian history. About 90 bodies were identified by Canadian medical examiners using dental records. For around 30 bodies, examiners used fingerprints and ante mortem (before death) X-rays. The large number of ante mortem dental X-rays meant that around 90 bodies had been identified by the end of October. The RCMP contacted relatives of victims to ask for medical histories and dental records. Blood samples from relatives were used in the DNA identification of victims.[34]

Legacy

Memorials and tributes

A memorial service was held in Zürich.[35] The following year a memorial service was held in Nova Scotia.[36]

Two memorials to those who died in the crash were established by the Government of Nova Scotia. One is to the east of the crash site at The Whalesback, a promontory one kilometre (0.6 mile) north of Peggys Cove.[37] The second is a more private, but much larger commemoration located west of the crash site near Bayswater Beach Provincial Park on the Aspotogan Peninsula in Bayswater.[38] Here, the unidentified remains of the victims are interred. A fund was established to fund maintenance of the memorials and the government passed an act to recognize them.[39][40] Various other charitable funds were also created, including one in the name of a young victim from Louisiana, Robert Martin Maillet, which provides money for children in need.[41]

A further permanent memorial, albeit not publicly accessible, was created inside the Operations Center at Zurich Airport where a simple plaque on the ground floor in the centre opening of a spiral staircase pays tribute to the victims.

In September 1999 Swissair, Delta, and Boeing (who had acquired McDonnell Douglas through a merger in 1997) agreed to share liability for the accident and offered the families of the passengers financial compensation.[42] The offer was rejected in favour of a $19.8 billion suit against Swissair and DuPont, the supplier of the Mylar insulation sheathing. A US federal court dismissed the claim in February 2002.[43]

Two paintings, including Le Peintre (The Painter) by Pablo Picasso, were on board the aircraft and were destroyed in the accident.[44]

Impacts on the industry

At the time of the accident, the McDonnell Douglas MD-11 was the only tri-jet airliner in production.[45] The MD-11 was produced as a freighter then; the last passenger version was delivered to Sabena in 1998. The last MD-11 overall was delivered to Lufthansa Cargo in 2001, as a freighter.

The crash of Flight 111 caused a strong blow to Swissair. Ironically, the IFE system on the aircraft that was blamed for causing the accident was installed by Swissair to attract more passengers in order to ease the airline's financial difficulties. Swissair finally went bankrupt shortly after the 9/11 attack in 2001, which caused a powerful disruption to the aviation transportation industry.[46]

After the crash, the flight route designator for Swissair's New York-Geneva route was changed to Flight 139, still performed by MD-11s. After Swissair's bankruptcy in 2002, Crossair received the international traffic rights of Swissair, and began operating flights as Swiss International Air Lines. At that time the flight designator was changed to flight LX 023, and operated by Airbus A330-200s.

Since the crash, there have been many television documentaries on Flight 111, including the CBC's The Fifth Estate, "The Investigation of Swissair 111", PBS's NOVA "Aircrash", and episodes of disaster shows like History Channel's Disasters of the Century, Discovery Channel's Mayday, National Geographic Channel's Seconds From Disaster and in March 2003 The Swiss television also broadcast a documentary called "Feuer an Bord - Die Tragödie von Swissair Flug 111" ("fire on board - the tragedy of Swissair flight 111").[47] NOVA created a classroom activity kit for school teachers, using the crash as an example of an aircraft crash investigation. The Canadian poet Jacob McArthur Mooney's 2011 collection, Folk, tangentially interrogates the disaster and its effect on Nova Scotia residents.[48]

In May 2007, the TSB released copies of the audio recordings of the air traffic control transmissions associated with the flight.[49][50] The transcripts of these recordings had been released in 1998 (within days of the crash), but the TSB had refused to release the audio on privacy grounds. The TSB argued that under Canada's Access to Information Act and Privacy Act, the audio recordings constituted personal information and were thus not disclosable. Canada's Federal Court of Appeal rejected this argument in 2006 in a legal proceeding concerned with air traffic control recordings in four other air accidents.[51] The Supreme Court of Canada did not grant leave to appeal that decision and consequently the TSB released a copy of the Swissair 111 air traffic control audio recordings to the Canadian Press, which had requested the recordings under the Access to Information Act.[52] Several key minutes of the air traffic control audio can be found on the Toronto Star web site.[53]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "Aviation Investigation Report, In-Flight Fire Leading to Collision with Water, Swissair Transport Limited McDonnell Douglas MD-11 HB-IWF Peggy's Cove, Nova Scotia 5 nm SW 2 September 1998" (PDF). Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 27 March 2003. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ↑ "ASN Aviation Safety Database". Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "Nova: Crash of Flight 111". PBS.org. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- ↑ Stoller, Gary (16 February 2003). "Doomed plane's gaming system exposes holes in FAA oversight". USA Today.

- 1 2 3 4 "Fire on Board". Mayday. Season 1. 2003. Discovery Channel Canada / National Geographic.

- ↑ "Air traffic control transcript for Swissair 111". PlaneCrashInfo.com. 2 September 1998. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "Location of debris field". TSB. Archived from the original on 2003-04-05 – via internet archive.

- 1 2 3 4 Virginia Beaton (8 September 2008). "Ceremonies mark a decade since Swissair Flight 111 crash" (PDF). Trident. 42 (8). Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ http://halifaxsar.ca/about/

- ↑ SARSCENE Winter 1998 Archived 25 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Butler, John Marshall (2001). Forensic DNA Typing: biology & technology behind STR markers. Academic Press, San Diego. ISBN 0-12-147951-X.

- ↑ Suzette Kettenhofen, Digital Information Specialist, Technology Integration, Navy Office of Information (10 September 1998). "U.S. Navy Assists With Recovery of Swissair Flight 111". Navy.mil. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy assists with recovery of Swissair Flight 111." (Archive) United States Navy. Retrieved on 6 September 2012.

- ↑ T.W. Wiggins Minor War Vessel Involvement

- ↑ Transportation Safety Board Archived 30 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Adamson, April. "229 Victims Knew Jet Was In Trouble Airport Inn Becomes Heartbreak Hotel Again." Philadelphia Inquirer. 4 September 1998. Retrieved on 9 March 2014.

- ↑ "Airlines act swiftly to help relatives New U.S. law required detailed emergency plan." Boston Globe at The Baltimore Sun. 4 September 1998. Retrieved on 9 March 2014.

- ↑ TSB STI-098 Supporting Technical Information

- ↑ "Fire downed Swissair 111". BBC News. 27 March 2003.

- ↑ "section 28 of the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act". Canadian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- ↑ "section 29 of the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act". Canadian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- ↑ "ATC transcript Swissair Flight 111 – 2 SEP 1998". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- ↑ the Toronto Star (accessed 25 May 2007).

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dYWwX9fieYw

- ↑ "Swissair crash may not have been an accident: ex-RCMP". CBC. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ "Names of Swissair Crash Victims," CNN

- ↑ "From Europe and New York, grieving families head to crash site," CNN

- ↑ cited in Corriere della Sera

- ↑ "Babolat: World's oldest tennis firm". BBC. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ "Roger R. Williams, MD (1944–1998)" (PDF). National Lipid Association. 1999. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ Chakravarti, Aravinda (14 January 1999). "Roger R. Williams, M.D. (1944–1998): Cardiovascular geneticist, physician, and gentle friend (page 1)". Genetic Epidemiology. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1999)16:1<1::AID-GEPI1>3.0.CO;2-D. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- 1 2 "BNL Scientists Perish in Crash". Brookhaven National Laboratory. 3 September 1998. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ↑ "Corriere della Sera, Archivio storico". Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Robb, Nancy. "229 people, 15 000 body parts: pathologists help solve Swissair 111’s grisly puzzles." Canadian Medical Association Journal. 26 January 1999. 160 (2). Pages 241–243. Retrieved on 10 June 2009.

- ↑ "SR 111-Trauerfeier: Medienservice und Programm." Swissair. 10 September 1998. Retrieved on 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Coordination and Planning Secretariat, Flight 111." Government of Nova Scotia. 26 August 1999. Retrieved on 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Swissair Flight 111 Memorial: Whalesback". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "Swissair Flight 111 Memorial: Bayswater". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "Articles on memorial maintenance difficulties ca 2002." International Aviation Safety Association. Retrieved on 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Flight 111 Special Places Memorial Act." Government of Nova Scotia. Retrieved on 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Man biking to Canada in honor of crash victim." The Advocate. 2 August 2000. Retrieved on 6 June 2009.

- ↑ "Swissair Offers to Settle in Crash". Washington Post. 6 August 1999.

- ↑ "Over $13 Million for Victims of Swissair Disaster". Rapoport Law Offices. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ↑ "Picasso Painting Lost in Crash". CBS News. Halifax, Nova Scotia. 14 September 1998. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ↑ "Only wide-cabin, 3-engine jetliner still in production". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. AP. 4 September 1998. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ "Swissair Takes a Gamble on New System". LosAngeles Post. 31 July 1996. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ "Feuer an Bord: Die Tragödie von Swissair Flug 111" (in German). SRF - Swiss Radio and Television (then SF). 27 March 2003. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ "Aircrash" (PDF). WGBH. 2003. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ↑ Dean Beeby. "Swissair recordings revive horrifying drama of deadly 1998 tragedy". Canadian Press. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ↑ "Swissair crash recordings revive drama of one of Canada's worst aviation disasters". 22 May 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ↑ "Canada (Information Commissioner) v. Canada (Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board) 2006 FCA 157".

- ↑ Dean Beeby (22 May 2007). "Doomed flight's tapes released". Toronto Star. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ↑ "Canadian Press video of last minutes of Swissair flight 111" (QuickTime). The Star. Toronto. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

Further reading

- Aviation Investigation Report, In-Flight Fire Leading to Collision with Water, Swissair Transport Limited McDonnell Douglas MD-11 HB-IWF Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia 5 nm SW 2 September 1998, Transportation Safety Board of Canada, 27 March 2003, retrieved 16 January 2016 – French version available here

- Kimber, Stephen (1999). Flight 111:The Tragedy of the Swissair Crash. Seal Books, Toronto. ISBN 0-7704-2840-1.

- Wilkins, David; Murphey, Cecil (January 2003). United by Tragedy: A Father's Story. Pacific Press Publishing Association. ISBN 0-8163-1980-4.

- Wilson, Budge (February 2016). After Swissair. Pottersfield Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swissair Flight 111. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swissair Flight 111 memorials. |

|

|

- Detailed report about the crash on Austrian Wings (German, published on 2 September 2013)

- Swissair – Information about the accident of SR111 – Swissair (Archive)

- Esquire July 2000 report "The Long Fall of One-Eleven Heavy" highlighting the human side of the accident

- Lloyd's of London

- "Lloyd's statement regarding Swissair crash site license application." Friday 19 May 2000. (Archive)

- "Lloyd's statement regarding the Swissair crash site." Tuesday 23 May 2000. (Archive)

- Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript and accident summary on tailstrike.com

- Swissair Flight 111 memorial site

- Swissair profile CNN

- Swissair crash warning to airlines, BBC