Surreal humour

| Surrealism |

|

Surrealist Manifesto |

Surreal humor (also known as absurdist humor) is a form of humor predicated on deliberate violations of causal reasoning, producing events and behaviors that are obviously illogical. Constructions of surreal humor tend to involve bizarre juxtapositions, non-sequiturs, irrational or absurd situations and expressions of nonsense.

The humor arises from a subversion of audience's expectations, so that amusement is founded on unpredictability, separate from a logical analysis of the situation. The humor derived gets its appeal from the fact that the situation described is so ridiculous or unlikely. The genre has roots in Surrealism in the arts.

Literary precursors

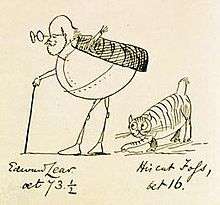

People speak of surreal humor when illogic and absurdity are used for humorous effect. Under such premises, people can identify precursors and early examples of surreal humor at least since the 19th century, such as Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, which both use illogic and absurdity (hookah-smoking caterpillars, croquet matches using live flamingos as mallets, etc.) for humorous effect. Many of Edward Lear's children stories and poems contain nonsense and are basically surreal in approach. For example, The Story of the Four Little Children Who Went Round the World (1871) is filled with contradictory statements and odd images intended to provoke amusement, such as the following:

After a time they saw some land at a distance; and when they came to it, they found it was an island made of water quite surrounded by earth. Besides that, it was bordered by evanescent isthmuses with a great Gulf-stream running about all over it, so that it was perfectly beautiful, and contained only a single tree, 503 feet high.[1]

Relationship with dadaism and futurism

In the early 20th century, several avant-garde movements, including the dadaists, surrealists, and futurists began to argue for an art that was random, jarring and illogical. The goals of these movements were in some sense serious, and they were committed to undermining the solemnity and self-satisfaction of the contemporary artistic establishment. As a result, much of their art was intentionally amusing.

A famous example is Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917), an inverted urinal signed "R. Mutt". This became one of the most famous and influential pieces of art in history, and one of the earliest examples of the found art movement. It is also a joke, relying on the inversion of the item's function as expressed by its title as well as its incongruous presence in an art exhibition.

Etymology and development

The word surreal first began to be used to describe a type of aesthetic of the early 1920s.

In addition to the avant-garde art movements, early surrealist comedy is found in the satirical and comedic elements of works of modern authors, who, like Lear and Carroll, wrote stories which dispensed with the normal rules of logic. Examples of this include the dark comedy of Franz Kafka, the stream of consciousness writings of James Joyce, Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and Hunter S. Thompson, or the poetry of Dylan Thomas and E. E. Cummings.

Surreal humor is also found frequently in avant-garde theatre such as Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead. In the United States, S. J. Perelman (1904-1979) has been identified as the first surrealist humor writer.[2] Artists like Yoko Ono, Andy Warhol, Donald Barthelme, Italo Calvino, John Hodgman, and many others have relied on this technique in their work.

Surrealist humor has played an important role in popular culture, especially since The Goon Show, Ernie Kovacs and The Firesign Theater. In the 1960s, surreal humor was combined with counter-culture in movements such as the Youth International Party and the Merry Pranksters, as well as in the work of psychedelic musicians such as The Beatles, Syd Barrett, Frank Zappa, The Residents, The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, Captain Beefheart, and the television series The Monkees.

Spike Milligan has been a great influence with his absurdist pieces. One of his earliest works in radio, The Goon Show, has inspired many other absurdist comedians and was incredibly popular at the time. Spike Milligan went on to create a TV show in 1969, Q..., which was a sketch show that further influenced the comedy troupe Monty Python. In turn, the Pythons influenced many with their groundbreaking series Monty Python's Flying Circus.

In the 1980s, when the 'alternative comedy' era had begun, absurdist comedians were working the circuit and started up The Comic Strip. With the success of The Comic Strip Presents..., featuring as one of the first aired pieces for Channel 4, the BBC decided to take the shelved series The Young Ones and create two seasons from 1982–84. This was a very absurdist sitcom based on four university students.

Both Monty Python and The Young Ones featured an intricate structure and many absurdities and non sequiturs.

In the late 1980s and then the 1990s, Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer were dominant in the world of British surreal comedy.

More recently, The Mighty Boosh has exploited the sitcom format for distinctly surreal purposes. A distinctly Pythonesque strand of surrealism is prevalent in the work of stand-up comedian Eddie Izzard, who often uses anthropomorphic constructs in order to tell a running joke, often splicing several jokes together throughout a two-hour show. The Mighty Boosh's Noel Fielding is known as a surrealist and has also worked on his own sketch show, Noel Fielding's Luxury Comedy, which includes numerous surreal characters such as a talking chocolate finger who is a P.E. teacher and a man with a winkle for a head.

Surrealist humor is predominately approached in cinema where the suspension of disbelief can be stretched to absurd lengths by logically following the consequences of unlikely, reversed or exaggerated premises. Luis Buñuel is a principal exponent of this, especially in The Exterminating Angel. Other examples include The Falls by Peter Greenaway, "Free Time" by The Bogus Group, and Brazil by Terry Gilliam.[3][4] As with satire, the humor is intended as an attack on particular norms and preconceptions rather than as pure entertainment.

Analysis

Drs. Mary K. Rodgers and Diana Pien analysed the subject in an essay entitled "Elephants and Marshmallows" (subtitled "A Theoretical Synthesis of Incongruity-Resolution and Arousal Theories of Humor"), and wrote that "jokes are nonsensical when they fail to completely resolve incongruities," and cited one of the many permutations of the elephant joke: "Why did the elephant sit on the marshmallow?" "Because he didn't want to fall into the cup of hot chocolate."[5]

"The joke is incompletely resolved in their opinion," noted Dr. Elliot Oring, "because the situation is incompatible with the world as we know it. Certainly, elephants do not sit in cups of hot chocolate."[6] Oring defined humor as not the resolution of incongruity, but "the perception of appropriate incongruity,"[7] that all jokes contain a certain amount of incongruity, and that absurd jokes require the additional component of an "absurd image," with an incongruity of the mental image.[8]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Humor. |

References

- Notes

- ↑ Lear, Edward. Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany, and Alphabets.

- ↑ McCaffery, Larry (1982). "An interview with Donald Barthelme". Partisan Review. 49: 185.

People like SJ Perelman and EB White—people who could do certain amazing things in prose. Perelman was the first true American surrealist—ranking with the best in the world surrealist movement.

- ↑ Vogel, Amos (2005). Film as a Subversive Art. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-49078-9.

- ↑ Williams, Linda (1992). Figures of Desire: An Analysis of Surrealist Film. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07896-9.

- ↑ Chapman, Antony J.; Foot, Hugh C., eds. (1977). It's A Funny Thing, Humor. Pergamon Press. pp. 37–40.

- ↑ Oring 2003, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Oring 2003, p. 14

- ↑ Oring, Elliott (1992). Jokes and Their Relations. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 21–22.

- Bibliography

- Oring, Elliott (2003). Engaging Humor. University of Illinois Press.