Sultana (steamboat)

Sultana at Helena, Arkansas, on April 26, 1865, a day before her destruction. A crowd of paroled prisoners covers her decks. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Sultana |

| Owner: | Initially Capt. Pres Lodwick, then a consortium including Capt. J. Cass Mason |

| Port of registry: |

|

| Route: | St. Louis to New Orleans |

| Builder: | John Litherbury Boatyard, Cincinnati |

| Launched: | January 3, 1863 |

| In service: | 1863 |

| Fate: | Exploded and sank, April 27, 1865, on Mississippi River seven miles north of Memphis, Tennessee. |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 1,719 tons |

| Length: | 260 feet |

| Beam: | 42 feet |

| Decks: | Four decks (including pilothouse) |

| Propulsion: | 34 ft (10 m) diameter paddlewheels |

| Capacity: | 376 passengers and cargo |

| Crew: | 85 |

Sultana was a Mississippi River side-wheel steamboat. On April 27, 1865, the boat exploded in the worst maritime disaster in United States history. Although designed with a capacity for only 376 passengers, she was carrying 2,427 when three of the boat's four boilers exploded and she burned to the waterline and sank near Memphis, Tennessee, killing an estimated 1,700 passengers.[1] This disaster has long been overshadowed in the press by other contemporary events; John Wilkes Booth, President Lincoln's assassin, was killed the day before.

The wooden steamboat was constructed in 1863 by the John Litherbury Boatyard[2] in Cincinnati, and intended for the lower Mississippi cotton trade. Registering 1,719 tons,[3] the steamer normally carried a crew of 85. For two years, she ran a regular route between St. Louis and New Orleans, frequently commissioned to carry troops.

The tragedy

.jpg)

Under the command of Captain J. Cass Mason of St. Louis, Sultana left St. Louis on April 13, 1865, bound for New Orleans, Louisiana.[4] On the morning of April 15, she was tied up at Cairo, Illinois when word reached the city that President Abraham Lincoln had been shot at Ford's Theater. Immediately, Mason grabbed an armload of Cairo newspapers and headed south to spread the news, knowing that telegraphic communication with the South had been almost totally cut off because of the war.[5] Upon reaching Vicksburg, Mississippi, Mason was approached by Lt. Col. Reuben Hatch, the chief quartermaster at Vicksburg. Hatch had a deal for Mason. Thousands of recently released Union prisoners of war that had been held by the Confederacy at the prison camps of Cahaba near Selma, Alabama, and Andersonville, in southwest Georgia, had been brought to a small parole camp outside of Vicksburg to await release to the North. The U.S. government would pay $5 per enlisted man and $10 per officer to any steamboat captain that would take a group north. Knowing that Mason was in need of money, Hatch suggested that if he could guarantee Mason a full load of about 1,400 prisoners, Mason would guarantee to give Hatch a kickback. Hoping to walk away with a pocketful of cash, Mason quickly agreed to the offered bribe.[6]

Leaving Vicksburg, the Sultana traveled down river to New Orleans, continuing to spread the news of Lincoln's assassination. On April 21, 1865, the Sultana left New Orleans with 75 to 100 cabin passengers, deck passengers, and a small amount of livestock. About an hour south of Vicksburg, one of the Sultana's four boilers sprang a leak. Under reduced pressure, the steamboat limped into Vicksburg to get the boiler repaired and to pick up her promised load of prisoners.[7]

While the paroled prisoners, primarily from the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia,[8] were brought from the parole camp to the Sultana, a mechanic was brought down to work on the leaky boiler. Although the mechanic wanted to cut out and replace a ruptured seam, Mason knew that such a job would take a few days and cost him his precious load of prisoners. By the time the repairs would be completed, the prisoners would have been sent home on other boats. Instead, Mason and his chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer, convinced the mechanic to make temporary repairs, hammering back the bulged boiler plate and riveting a patch of lesser thickness over the seam. Instead of taking two or three days, the temporary repair took only one. During her time in port, and while the repair was being made, the Sultana took on the paroled prisoners.[9]

Although Hatch had suggested that Mason might get as many as 1,400 released Union prisoners, a mix-up with the parole camp books and suspicion of bribery from other steamboat captains caused the Union officer in charge of the loading, Captain George Williams, to place every man at the parole camp on board the Sultana.[10] Although the Sultana had a legal capacity of only 376, by the time she backed away from Vicksburg on the night of April 24, 1865, she was severely overcrowded with more than 2,100 paroled prisoners. Many of the men had been weakened by their incarceration in the Confederate prison camps and associated illnesses. The men were packed into every available space, and the overflow was so severe that in some places, the decks began to creak and sag and had to be supported with heavy wooden beams.[11]

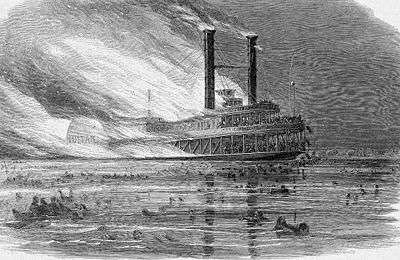

The Sultana spent two days traveling upriver, fighting against one of the worst spring floods in the river's history. At some places, the river overflowed the banks and spread out three miles wide. Trees along the river bank were almost completely covered, until only the very tops of the trees were visible above the swirling, powerful water.[12] On April 26, the Sultana stopped at Helena, Arkansas, where photographer T.W. Bankes took a picture of the grossly overcrowded vessel.[13] Near 7:00 p.m., the Sultana reached Memphis, Tennessee, and the crew began unloading 120 tons of sugar from the hold. Near midnight, the Sultana left Memphis, went a short distance upriver to take on a new load of coal and then started north again.[14]

Near 2:00 a.m. on April 27, 1865, when the Sultana was just seven miles north of Memphis, her boilers suddenly exploded.[15] First one boiler exploded, followed a split second later by two more. The cause of the explosion was too much pressure and low water in the boilers. There was reason to believe allowable working steam pressure was exceeded in an attempt to overcome the spring river current. The enormous explosion flung some of the passengers on deck into the water, and destroyed a large section of the boat. The forward part of the upper decks collapsed into the exposed furnace boxes which soon caught fire and turned the remaining superstructure into an inferno. Survivors of the explosion panicked and raced for the safety of the water but in their weakened condition soon ran out of strength and began to cling to each other. Whole groups went down together.[16]

While this fight for survival was taking place, the southbound steamer Bostona II, coming downriver on her maiden voyage,[17] arrived at about 3:00 a.m., an hour after the explosion, and arrived at the site of the burning wreck to rescue scores of survivors. At the same time, dozens of people began to float past the Memphis waterfront, calling for help until they were noticed by the crews of docked steamboats and U.S. warships who immediately set about rescuing the half-drowned victims.[18] Eventually, the hulk of the Sultana drifted about six miles to the west bank of the river, and sank at around 9:00 a.m. near Mound City and present-day Marion, Arkansas, about seven hours after the explosion.[19] Other vessels joined the rescue, including the steamers Silver Spray, Jenny Lind, and Pocohontas, and the navy tinclad Essex and the sidewheel gunboat USS Tyler.[20]

Passengers who survived the initial explosion had to risk their lives in the icy spring runoff of the Mississippi or burn with the boat.[21] Many died of drowning or hypothermia. Some survivors were plucked from the tops of semi-submerged trees along the Arkansas shore. Bodies of victims continued to be found downriver for months, some as far as Vicksburg. Many bodies were never recovered. Sultana's officers, including Captain Mason, were among those who perished.[22]

About 700 survivors, many with horrible burns, were transported to hospitals in Memphis. Up to 200 of them died later from burns or exposure. Newspaper accounts indicate that the people of Memphis had sympathy for the victims despite the fact that they had recently been enemies. The Chicago Opera Troupe, a minstrel group, staged a benefit, while the crew of Essex raised $1,000.[23]

In spite of the enormity of the disaster, no one was ever held accountable. Capt. Frederick Speed, a Union officer who sent the 2,100 paroled prisoners into Vicksburg from the parole camp, was charged with grossly overcrowding the Sultana and found guilty. However, the guilty verdict was overturned by the judge advocate general of the army on grounds that Speed had been at the parole camp all day and had never placed one single soldier on board the Sultana.[24] Captain Williams, who had placed the men on board, was a regular army officer and graduate of West Point, so the military refused to go after one of their own.[25] And Colonel Hatch, who had concocted a bribe with Captain Mason to crowd as many men as possible on the Sultana, had quickly quit the service and was no longer accountable to a military court. In the end, no one was ever held accountable for the greatest maritime disaster in United States history.[26]

Monuments and historical markers to Sultana and her victims have been erected at Memphis;[27] Muncie, Indiana;[28] Marion;[29] Vicksburg; Cincinnati;[30] Knoxville;[31] Hillsdale, Michigan;[32] and Mansfield, Ohio.[33]

Casualties

The exact death toll is unknown, although the most recent evidence indicates more than 1,700, almost 200 higher than the 1,512 deaths attributed to the Titanic disaster on the North Atlantic 47 years later. The official count by the United States Customs Service was 1,800. Final estimates of survivors are about 550. Many of the dead were interred at the Memphis National Cemetery.[34]

Cause

The official cause of the Sultana disaster was determined to be mismanagement of water levels in the boiler, exacerbated by the fact that the vessel was severely overcrowded and top heavy. As the steamboat made her way north following the twists and turns of the river, she listed severely to one side then the other. Her four boilers were interconnected and mounted side-by-side, so that if the boat tipped sideways, water would tend to run out of the highest boiler. With the fires still going against the empty boiler, this created hot spots. When the boat tipped the other way, water rushing back into the empty boiler would hit the hot spots and flash instantly to steam, creating a sudden surge in pressure. This effect of careening could have been minimized by maintaining high water levels in the boilers. The official inquiry found that the boat's boilers exploded due to the combined effects of careening, low water level, and a faulty repair to a leaky boiler made a few days earlier.

In 1888, a St. Louis resident named William Streetor claimed that his former business partner, Robert Louden, made a death bed confession of having sabotaged Sultana by a coal torpedo.[35] Louden, a former Confederate agent and saboteur who operated in and around St. Louis, had the opportunity and motive to attack it and may have had access to the means. (Thomas Edgeworth Courtenay, the inventor of the coal torpedo, was a former resident of St. Louis and was involved in similar acts of sabotage against Union shipping interests.) Supporting Louden's claim are eyewitness reports that a piece of artillery shell was observed in the wreckage. Louden's claim is controversial, however, and most scholars support the official explanation. The location of the explosion, from the top rear of the boilers, far away from the fireboxes, tends to indicate that Louden's claim of sabotage was pure bravado.[36][37]

The episode of History Detectives, which aired on July 2, 2014, reviewed the known evidence and then focused on the question of why the steamboat was allowed to be crowded to several times its normal capacity before departure. The report blamed quartermaster Hatch, an individual with a long history of corruption and incompetence, who was able to keep his job due to political connections: he was the younger brother of Illinois politician Ozias M. Hatch, an advisor and close friend of President Lincoln. Throughout the war, Reuben Hatch had shown incompetence as a quartermaster and competence as a thief, bilking the government out of thousands of dollars. Although brought up on courts-martial charges, Hatch managed to get letters of recommendation from such noted authorities as President Abraham Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and General of the Army Ulysses S. Grant. The letters reside in the National Archives in Washington DC. Hatch refused three separate subpoenas to appear before Captain's Speed's trial and give testimony before dying in 1871, having escaped justice due to his numerous highly placed patrons—including two presidents.[38]

Survivors

In December 1885, the survivors living in the northern states of Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio began attending annual reunions, forming the National Sultana Survivors' Association. Eventually, the group would settle on meeting in the Toledo, Ohio area. Perhaps inspired by their northern comrades, a southern group of survivors, men from Kentucky and Tennessee began meeting in 1889 around Knoxville, Tennessee. Both groups met as close to the April 27 anniversary date as possible, corresponded with each other, and shared the title National Sultana Survivors' Association.

By the mid-1920s, only a handful of survivors were able to attend the reunions. In 1929, only two men attended the southern reunion. The next year, only one man showed up. The last southern survivor, Cpl. Samuel W. Jenkins of the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry, died on January 19, 1933 at age 84. The last of the northern survivors, Pvt. Albert Norris of the 76th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, age 94, died at his home on January 9, 1936, 71 years after the burning and sinking of the steamboat Sultana.[39]

Remnants found

In 1982, a local archaeological expedition, led by Memphis attorney Jerry O. Potter, uncovered what was believed to be the wreckage of Sultana. Blackened wooden deck planks and timbers were found about 32 feet (10 m) under a soybean field on the Arkansas side, about 4 miles (6 km) from Memphis. The Mississippi River has changed course several times since the disaster, leaving the wreck under dry land and far from today's river. The main channel now flows about 2 miles (3 km) east of its 1865 position.[22]

In culture

Artwork

- The J. Mack Gamble Fund of the Sons and Daughters of Pioneer Rivermen and the Association of Sultana Descendants and Friends sponsored a mural by Louisiana artist Robert Dafford and his crew, entitled The Sultana Departs from Vicksburg, as one of the Vicksburg Riverfront Murals. It was dedicated on April 9, 2005.[40][41]

Novelization

- Hendricks, Nancy (2015). Terrible Swift Sword: Long Road to the Sultana. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1507764688.

- Thom, James Alexander (2015). Fire in the Water. Blue River Press. ISBN 978-1935628569.

Music

- The band Beehoover paid tribute with their song "Sultana", which was released on their Concrete Catalyst album (2010)

- Cory Branan - "The Wreck of the Sultana"

- Jay Farrar of the band Son Volt wrote a song called "Sultana", paying tribute to "the worst American disaster of the maritime". Farrar calls the boat "the Titanic of the Mississippi" in the song, which was released on the American Central Dust album (2009)[42]

See also

References

- ↑ Berryman, H.E.; Potter, J.O.; Oliver, S. (1988). "The ill-fated passenger steamer Sultana: an inland maritime mass disaster of unparalleled magnitude". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 33 (3): 842–850.

- ↑ Given as the "John Lithoberry Shipyard" on Ohio Historical Marker 18-31 (1999) on the Ohio River at Sawyer Point.

- ↑ Berry (1892), p. 7

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 12

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 27-28

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 29-31

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 33, 34-35, 38, 40-41

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 226-290

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 40

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 50, 55-56

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 62

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 24

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 72

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 74-79

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 79

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 79-85

- ↑ Potter, Jerry O. "Sultana: A Tragic Postscript to the Civil War". American History Magazine.

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 129

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 164

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 146-147, 168-168, 169-172, 174-176

- ↑ Bennett, Robert Frank, CDR USCG (March 1976). "A Case of Calculated Mischief". Proceedings: 77–83.

- 1 2 Harvey, Hank (October 27, 1996). "The Sinking of the Sultana". The Blade. "Section C, pp. 6,3". Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Memphis Daily Bulletin, and Memphis Daily Appeal, various dates, April 1865

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 197-202

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 202

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 198, 200, 202

- ↑ "Historic Memphis Elmwood Cemetery". Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Sultana Disaster Monument". Find a Grave. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Sultana Historic Marker". Arkansas: The Natural State. Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "The Sultana". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Sultana Monument -- Civil War". East Tennessee River Valley GeoTourism Guide. National Geographic. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Sultana Memorial". Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Sultana Tragedy". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 206

- ↑ "The Sultana Disaster (Coal Torpedo theory)". Civil War St Louis. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ↑ Tidwell, William A. (1995). "April '65". Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press: 52.

- ↑ Rule, G.E.; Rule, Deb (December 2001). "The Sultana: A case for sabotage". North and South Magazine. 5 (1).

- ↑ Salecker, Disaster on the Mississippi, p. 193-194, 196-197

- ↑ Salecker. Disaster on the Mississippi. pp. 212–215.

- ↑ "The Sultana Departs from Vicksburg". Vicksburg Riverfront Murals. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ↑ Huffman, Alan (October 2009). "Surviving the Worst: The Wreck of the Sultana at the End of the American Civil War". Mississippi Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ↑ Deusner, Stephen. "American Central Dust". Pitchfork Media (Review). Retrieved 31 January 2013.

Further reading

- Bearss, Margie Riddle (Spring 1978). "Messenger of Lincoln Death Herself Doomed". The Lincoln Herald: 49–51.

- Berry, Chester D. (2005) [1892]. Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 1-57233-372-3.

- Bryant, William O. (1990). Cahaba Prison and the "Sultana" Disaster. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0468-1.

- Elliott, Joseph Taylor. (1913). The Sultana Disaster. E.J. Hecker. Indiana Historical Society Publications, v. 5, no. 3.

- Hendricks, Nancy (2015). Terrible Swift Sword: Long Road to the Sultana. ISBN 978-1-5077-6468-8.

- Huffman, Alan (2009). Sultana: Surviving the Civil War, Prison, and the Worst Maritime Disaster in American History. Collins. ISBN 0-06-147054-6.

- Potter, Jerry O. (1992). The Sultana Tragedy: America's Greatest Maritime Disaster. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 0-88289-861-2.

- Rule, G. E.; Rule, Deb. "The Sultana: A case for sabotage". North and South Magazine. 5 (1).

- Salecker, Gene Eric (1996). Disaster on the Mississippi: the Sultana Explosion, April 27, 1865. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-739-2.

- Salecker, Gene Eric (May 2002). "A Tremendous Tumult and Uproar". America's Civil War. 15 (2).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sultana (ship, 1863). |

- "Sultana: Titanic of the Mississippi - Investigation with several videos".

- On This Date in 1865: Tragedy on the Mississippi - Sultana Explodes - Thousands Die

- Raising The Sultana http://sultana.cdi.astateweb.org/home

- Steamboat Sultana: Biographical Information

- A Soldier's Story (Sultana Remembered)

- Sultana Disaster Records - Records relating to the explosion of the steamer Sultana, including lists of those aboard the boat.

Coordinates: 35°11′26″N 90°6′52″W / 35.19056°N 90.11444°W