Subspecies of Canis lupus

| Canis lupus species Temporal range: 0.7–0 Ma Middle Pleistocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

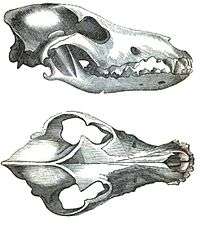

_C._lupus_subspecies_skulls.jpg) | |

| Skulls of various gray wolf subspecies from North America | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Subfamily: | Caninae |

| Tribe: | Canini |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lupus |

| Binomial name | |

| Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758[2] | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Numerous and disputed | |

| |

| Historical range of wild subspecies of C. lupus | |

Canis lupus has 37 subspecies currently described, including the dingo, Canis lupus dingo, and the domestic dog, Canis lupus familiaris, and many subspecies of wolf throughout the Northern Hemisphere. The nominate subspecies is Canis lupus lupus.

Canis lupus is assessed as least concern by the IUCN, as its relatively widespread range and stable population trend mean that the species, at global level, does not meet, or nearly meet, any of the criteria for the threatened categories. However, some local populations are classified as endangered,[1] and some subspecies are endangered or extinct.

Biological taxonomy is not fixed, and placement of taxa is reviewed as a result of new research. The current categorization of subspecies of Canis lupus is shown below. Also included are synonyms, which are now discarded duplicate or incorrect namings, or in the case of the domestic dog synonyms, old taxa referring to subspecies of domestic dog which, when the dog was declared a subspecies itself, had nowhere else to go. Common names are given but may vary, as they have no set meaning.

Taxonomy

Canis lupus was recorded by Carl Linnaeus in his publication Systema Naturae in 1758.[3] The Latin classification translates into English as "dog wolf". The subspecies of Canis lupus are listed in Mammal Species of the World.[4][5] The nominate subspecies is the Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus lupus),[5] also known as the common wolf.[6]

For Eurasia, in 1995 mammalogist Robert Nowak recognized five subspecies from Eurasia based on skull morphology; C. l. lupus, C. l. albus, C. l. pallipes, C. l. cubanensis and C. l. communis.[7] In 2003, Nowak also recognized the distinctiveness of C. l. arabs, C. l. hattai, C. l. hodophilax and C. l. lupaster.[8]

In 1944, American zoologist Edward Goldman recognized as many as 23 subspecies in North America, based on morphology alone.[9] In 1959, E. Raymond Hall proposed that there had been 24 subspecies of lupus in North America.[10] In 1970, L David Mech proposed that there was "probably far too many sub specific designations...in use" as most did not exhibit enough points of differentiation to be classified as a separate subspecies.[11] The 24 subspecies were accepted by many authorities in 1981 and these were based on morphological or geographical differences or a unique history.[12] However, in 1996, Ronald M. Nowak and Nick E. Federoff challenged Hall's 24 subspecies and proposed that based on detailed skull comparisons there had only been five: C. l. occidentalis, C. l. nubilus, C. l. arctos, C. l. baileyi and C. l. lycaon.[13] Both classifications are accepted in North America.

As of 2005,[4] 37 subspecies of C. lupus are recognised by MSW3, however the classification of several as either species or subspecies has recently been challenged.

- Further information: Disputed subspecies and species

History of classification

- See further: Evolution of the wolf - Divergence with the coyote

Eastern and red wolves

In 2000, a genetic study of canids from Algonquin Provincial Park indicated that C. l. lycaon was a separate species from C. lupus, more closely related to C. rufus.[14] In a monograph prepared within the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USF&WS), Chambers et al. (2012) reviewed many genetic studies and concluded that the eastern wolf and red wolf are separate species from the gray wolf, having originated in North America 150,000–300,000 years ago from the same line as coyotes. The Chambers review concluded that the subspecific status of C. l. arctos is doubtful, as Arctic wolf populations do not possess unique haplotypes.[15] However, the Chambers review became controversial, forcing the USF&WS to commission a peer review of it, known as NCAES (2014).[16] This peer review concluded that "virtually all taxonomic conclusions from Chambers et al. are accepted uncritically." Director of RESOLVE's Science Program, Steven Courtney, who was in charge of the peer review, had also noted that the Chambers conclusion that the eastern wolf should be listed outside the species limits of the gray wolf was based primarily on two non-recombining markers – those being mtDNA and sex chromosome – which the other panelists agreed unanimously "is insufficient to determine the existence of a species and specifically is completely insufficient for ruling out the alternative hypothesis that the pattern is explained by ancient (and recent) hybridization between C. lupus and C. latrans". Evolutionary biologist Dr. Robert Wayne of the UCLA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology further elaborated that the Chambers review on the taxonomy of the eastern wolf not only suffered from insufficient sampling but that it was also biased in terms of attributing the presences of the gray wolf Y chromosomes in the modern day eastern wolves to two unfounded hypotheses: that C. lupus was historically absent in the eastern USA by C. lycaon followed with the suggestion of the former's invasion into the eastern third of North America and later introgressing into the latter's gene pool, and that the gray wolf Y chromosomes discovered in the Algonquin Provincial Park's eastern wolf samples originated from domestic dogs.

Two subsequent reviews of updated research based on the 2013 and 2014 reviews, one commissioned to the Wildlife Management Institute by the USFWS, and one journal review, concluded that historically there were four unique canid species in North America, gray wolf, eastern wolf, coyote, and dog, and that "the red wolf may be conspecific with the eastern wolf".[17][18] This view consistent with the idea that the coyote and gray wolf did not historically range into the southeastern United States.[17] These reviews and a 2015 genetics study, the most comprehensive to date,[19] led the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in May, 2015 to change the designation of the eastern wolf back into a distinct species, Canis lycaon. However, the previous assertion that gray wolves did not occur in the eastern third of the United States is still heavily ill-founded by the newer genetic study's lead authors, such as Dr. Linda Y. Rutledge, who noted in the conclusions that "the recognition of the eastern wolf as a separate species does not exclude the possibility that a grey wolf × eastern wolf hybrid animal (previously identified as Canis lupus lycaon, boreal/Ontario-type), similar to a Great Lakes boreal wolf currently located in the Great Lakes states and across Manitoba, northern Ontario, and northern Quebec, historically inhabited the northeastern United States alongside eastern wolves, and there is some evidence to support the historical presence of both Canis types." The study also suggests that the coyote markers present in the Canis lupus populations that currently occupy the western Great Lakes states and western Ontario may have been historically circuited into the population by the eastern wolves since pure gray wolves in the wild rarely hybridize with coyotes whereas eastern wolves have a history of hybridizing with both species.

List of subspecies

Subspecies recognized by MSW3 as of 2005[20] and divided into Old World and New World:[21]

Eurasia and Australia

| Subspecies | Image | Authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurasian wolf Canis lupus lupus (nominate subspecies) |

.jpg) |

Linnaeus 1758[22] | Generally a large subspecies with rusty ocherous or light grey fur.[23] | Has the largest range among wolf subspecies and is the most common in Europe and Asia, ranging through Western Europe, Scandinavia, Caucasus, Russia, China, Mongolia, and the Himalayan Mountains. Habitat overlaps with Indian wolf in some regions of Turkey. | altaicus (Noack, 1911), argunensis (Dybowski, 1922), canus (Sélys Longchamps, 1839), communis (Dwigubski, 1804), deitanus (Cabrera, 1907), desertorum (Bogdanov, 1882), flavus (Kerr, 1792), fulvus (Sélys Longchamps, 1839), italicus (Altobello, 1921), kurjak (Bolkay, 1925), lycaon (Trouessart, 1910), major (Ogérien, 1863), minor (Ogerien, 1863), niger (Hermann, 1804), orientalis (Wagner, 1841), orientalis (Dybowski, 1922), signatus (Cabrera, 1907)[24] |

| Tundra wolf Canis lupus albus |

|

Kerr 1792[25] | A large, light-furred subspecies.[26] | Northern tundra and forest zones in the European and Asian parts of Russia and Kamchatka. Outside Russia, its range includes the extreme north of Scandinavia[26] | dybowskii (Domaniewski, 1926), kamtschaticus (Dybowski, 1922),

turuchanensis (Ognev, 1923)[27] |

| Arabian wolf Canis lupus arabs |

|

Pocock 1934[28] | A small, "desert adapted" wolf that is around 66 cm tall and weighs, on average, about 18 kg.[29] Its fur coat varies from short in the summer and long in the winter, possibly because of solar radiation.[30] | Southern Israel, Southern and western Iraq, Oman, Yemen, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and probably some parts of the Sinai Peninsula | |

| Steppe wolf Canis lupus campestris |

|

Dwigubski 1804 | A wolf of average size with short, coarse and sparse fur.[31] | Northern Ukraine, southern Kazakhstan, Caucasus and Trans-Caucasus[31] | bactrianus (Laptev, 1929), cubanenesis (Ognev, 1923), desertorum (Bogdanov, 1882)[32] |

| Tibetan wolf Canis lupus chanco |

|

Gray 1863 | A small subspecies rarely exceeding 45 kg in weight. It is of a light, whitish-grey color, with an admixture of brownish tones on the upper part of the body[33] | Central Asia from Turkestan, Tien Shan throughout Tibet to Mongolia, Northern China, Shensi, Sichuan, Yunnan, the Western Himalayas in Kashmir from Chitral to Lahul.[34] Also occurs in the Korean peninsula[35] | coreanus (Abe, 1923), dorogostaiskii (Skalon, 1936), ekloni (Przewalski, 1883), filchneri (Matschie, 1907), karanorensis (Matschie, 1907), laniger (Hodgson, 1847), niger (Sclater, 1874), tschiliensis (Matschie, 1907)[36] |

| Dingo Canis lupus dingo |

|

Meyer 1793 | Generally 52–60 cm tall at the shoulders and measures 117 to 124 cm from nose to tail tip. The average weight is 13 to 20 kg.[37] Fur color is mostly sandy to reddish brown, but can include tan patterns and be occasionally black, light brown, or white[38] | Australia, ancient India, Indonesia, and New Guinea | antarcticus (Kerr, 1792), australasiae (Desmarest, 1820), australiae (Gray, 1826), dingoides (Matschie, 1915), macdonnellensis (Matschie, 1915), novaehollandiae (Voigt, 1831), papuensis (Ramsay, 1879), tenggerana (Kohlbrugge, 1896), harappensis (Prashad, 1936), hallstromi (Troughton, 1957)[39] |

| Domestic dog Canis lupus familiaris |

|

Linnaeus 1758 | The dog is a divergent subspecies of the gray wolf and was derived from a now-extinct population of Late Pleistocene wolves.[21][40][41] Through selective pressure and selective breeding, the dog has developed into hundreds of varied breeds, and shows more behavioral and morphological variation than any other land mammal.[42] | Worldwide | aegyptius (Linnaeus, 1758), alco (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), americanus (Gmelin, 1792), anglicus (Gmelin, 1792), antarcticus (Gmelin, 1792), aprinus (Gmelin, 1792), aquaticus (Linnaeus, 1758), aquatilis (Gmelin, 1792), avicularis (Gmelin, 1792), borealis (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), brevipilis (Gmelin, 1792)

cursorius (Gmelin, 1792) domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) extrarius (Gmelin, 1792), ferus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), fricator (Gmelin, 1792), fricatrix (Linnaeus, 1758), fuillus (Gmelin, 1792), gallicus (Gmelin, 1792), glaucus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), graius (Linnaeus, 1758), grajus (Gmelin, 1792), hagenbecki (Krumbiegel, 1950), haitensis (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), hibernicus (Gmelin, 1792), hirsutus (Gmelin, 1792), hybridus (Gmelin, 1792), islandicus (Gmelin, 1792), italicus (Gmelin, 1792), laniarius (Gmelin, 1792), leoninus (Gmelin, 1792), leporarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), major (Gmelin, 1792), mastinus (Linnaeus, 1758), melitacus (Gmelin, 1792), melitaeus (Linnaeus, 1758), minor (Gmelin, 1792), molossus (Gmelin, 1792), mustelinus (Linnaeus, 1758), obesus (Gmelin, 1792), orientalis (Gmelin, 1792), pacificus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), plancus (Gmelin, 1792), pomeranus (Gmelin, 1792), sagaces (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), sanguinarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), sagax (Linnaeus, 1758), scoticus (Gmelin, 1792), sibiricus (Gmelin, 1792), suillus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), terraenovae (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), terrarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), turcicus (Gmelin, 1792), urcani (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), variegatus (Gmelin, 1792), venaticus (Gmelin, 1792), vertegus (Gmelin, 1792)[43] |

| †Hokkaidō wolf Canis lupus hattai |

| | |

Kishida 1931 | Similar in size and related to the gray wolves of North America.[44] | Hokkaido and Sakhalin islands,[45][46]:p42 the Kamchatka peninsula, and Iturup and Kunashir islands just to the east of Hokkaido in the Kuril archipelago.[46]:p42 | rex (Pocock, 1935)[47] |

| †Japanese wolf Canis lupus hodophilax |

|

Temminck 1839 | Smaller in size compared to other gray wolves except for the Arabian wolf (Canis lupus arabs)[46]:p53 | Japanese islands of Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū (but not Hokkaido)[48][49] | hodopylax (Temminck, 1844), japonicus (Nehring, 1885)[50] |

| Indian wolf Canis lupus pallipes |

|

Sykes 1831 | A small wolf with pelage shorter than that of northern wolves, and with little to no underfur.[51] Fur color ranges from greyish red to reddish white with black tips. The dark V shaped stripe over the shoulders is much more pronounced than in northern wolves. The underparts and legs are more or less white.[52] | India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and southern Israel | |

North America

| Subspecies | Image | Authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| † Kenai Peninsula wolf Canis lupus alces |

Goldman 1941[53] | A very large subspecies similar to pambasileus.[54] | Kenai Peninsula | ||

| Arctic wolf Canis lupus arctos |

|

Pocock 1935[55] | A medium-sized, almost completely white subspecies.[56] | Melville Island (Northwest Territories and Nunavut) and Ellesmere Island | |

| Mexican wolf Canis lupus baileyi |

|

Nelson and Goldman 1929[57] | Smallest of North America's gray wolves, with dark fur.[58] | Northern Mexico, western Texas, southern New Mexico, and southeastern and central Arizona | |

| † Newfoundland wolf Canis lupus beothucus |

|

G. M. Allen and Barbour 1937 | A medium-sized, white furred subspecies.[59] | Newfoundland | |

| † Bank's Island Tundra wolf Canis lupus bernardi |

Anderson 1943 | A large, slender subspecies with a narrow muzzle and large carnassials.[60] | Limited to Banks and Victoria Islands in the arctic | banksianus (Anderson, 1943)[61] | |

| British Columbia wolf Canis lupus columbianus |

|

Goldman 1941 | Yukon, British Columbia, and Alberta | ||

| Vancouver Island wolf Canis lupus crassodon |

Hall 1932 | A medium-sized subspecies with grayish fur.[62] | Vancouver Island, British Columbia | ||

| † Florida black wolf Canis lupus floridanus |

_Louisiana_black_wolf.png) |

Miller 1912 | A jet black wolf that is described as being extremely similar to the red wolf in both size and weight.[63] This subspecies became extinct in 1908.[64] | Florida | |

| † Cascade mountain wolf Canis lupus fuscus |

Richardson 1839 | A cinnamon colored wolf similar to columbianus and irremotus, but darker in color.[65] | Cascade Range | ||

| † Gregory's wolf Canis lupus gregoryi |

Goldman 1937[66] | A medium-sized subspecies, though slender and tawny, its coat contains a mixture of various colors, including black, grey, white, and cinnamon.[66] | In and around the lower Mississippi River basin | gigas (Townsend, 1850)[67] | |

| †Manitoba wolf Canis lupus griseoalbus |

Baird 1858 | North Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba | knightii (Anderson, 1945)[68] | ||

| Hudson Bay wolf Canis lupus hudsonicus |

Goldman 1941 | A light-colored subspecies similar to occidentalis, but smaller.[69] | Northern Manitoba and the Northwest Territories | ||

| Northern Rocky Mountains wolf Canis lupus irremotus |

Goldman 1937[66][70] | A medium to large-sized subspecies with pale fur.[71] | Northern Rocky Mountains | ||

| Labrador wolf Canis lupus labradorius |

|

Goldman 1937[66] | A light-colored, medium-sized subspecies.[72] | Labrador and northern Quebec; recent confirmed sightings on Newfoundland[73][74] | |

| Alexander Archipelago wolf Canis lupus ligoni |

Goldman 1937[66] | A medium-sized, dark colored subspecies.[75] | Alexander Archipelago, Alaska | ||

| Eastern (timber) wolf Canis lupus lycaon |

.jpg) |

Schreber 1775 | A small, dark-colored form.[76] | Mainly occupies the area in and around Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, and also ventures into adjacent parts of Quebec, Canada. It also may be present in Minnesota and Manitoba | canadensis (de Blainville, 1843), ungavensis (Comeau, 1940)[77] |

| Mackenzie River wolf Canis lupus mackenzii |

Anderson 1943 | A subspecies with variable fur and intermediate in size between occidentalis and manningi.[78] | Northwest Territories | ||

| Baffin Island wolf Canis lupus manningi |

Anderson 1943 | The smallest gray wolf of the arctic, with white, buffy fur.[79] | Baffin Island | ||

| † Mogollon mountain wolf Canis lupus mogollonensis |

Goldman 1937[66] | A small, dark-colored subspecies, intermediate in size between youngi and baileyi.[80] | Arizona and New Mexico | ||

| †Texas (gray) wolf Canis lupus monstrabilis |

Goldman 1937[66] | Similar in size and color to C. lupus mogollonensis.[81] | Texas and New Mexico | niger (Bartram, 1791)[82] | |

| Great Plains wolf Canis lupus nubilus |

|

Say 1823 | A light-furred, medium-sized subspecies.[83] | Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Single wolves have been reported in the Dakotas and as far south as Nebraska | variabilis (Wied-Neuwied, 1841)[84] labradorius, irremotus, youngi (Goldman, 1937) |

| Northwestern wolf Canis lupus occidentalis |

|

Richardson 1829 | A very large, usually light-colored subspecies.[85] | Alaska, Yukon, Northwest Territories, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Northwestern United States | sticte (Richardson, 1829), ater (Richardson, 1829),[86] alces (Goldman, 1941), ater (Richardson, 1829), mackenzii (Anderson, 1943 (1908), pambasileus (Elliot, 1905), sticte (Richardson, 1829), tundrarum (Miller, 1912) |

| Greenland wolf Canis lupus orion |

_Greenland_draught_wolf.jpg) |

Pocock 1935 | Greenland and Queen Elizabeth Islands[87] | ||

| Yukon wolf Canis lupus pambasileus |

|

Elliot 1905 | Larger in skull and tooth proportions than C. l. occidentalis, with fur that is black to white or a mix of both in color.[88] | Alaska Interior and Yukon, save for the tundra region of the Arctic Coast.[89] | |

| Red wolf formerly Canis lupus rufus now Canis rufus |

|

Audubon and Bachman 1851 | Has a brownish or cinnamon pelt, with grey and black shading on the back and tail. Generally intermediate in size between other American wolf subspecies and coyotes. Like other wolves, it has almond-shaped eyes, a broad muzzle and a wide nosepad, though like the coyote, its ears are proportionately larger. It has a deeper profile, a longer and broader head than the coyote, and has a less prominent ruff than wolves[90] | Eastern North Carolina[91] | |

| Alaskan tundra wolf Canis lupus tundrarum |

|

Miller 1912 | A large, white-colored wolf closely resembling C. l. pambasileus, though lighter in color.[92] | Barren grounds of the Arctic Coast region from near Point Barrow eastward toward Hudson Bay and probably northwards to the Arctic Archipelago[93] | |

| †Southern Rocky Mountains wolf Canis lupus youngi |

Goldman 1937[66] | A light-colored, medium-sized subspecies closely resembling C. l. nubilus, though larger, with more blackish-buff hairs on the back.[94] | Southeastern Idaho, southwestern Wyoming, northeastern Nevada, Utah, western and central Colorado, northwestern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico |

Disputed subspecies and species

Eurasia

_C._l._lupus_%26_C._l._italicus.jpg)

Apennine wolf

The Italian wolf was first recognised as a distinct subspecies Canis lupus italicus in 1921 by zoologist Giuseppe Altobello.[95] Altobello's classification was later rejected by several authors, including Reginald Innes Pocock, who synonymised C. l. italicus with C. l. lupus.[96] In 2002, the noted paleontologist R.M. Nowak reaffirmed the morphological distinctiveness of the Italian wolf and recommended the recognition of Canis lupus italicus.[96] A number of DNA studies have found the Italian wolf to be genetically distinct.[97][98] In 2004, the genetic distinction of the Italian wolf subspecies was supported by analysis which consistently assigned all the wolf genotypes of a sample in Italy to a single group. This population also showed a unique mitochondrial DNA control-region haplotype, the absence of private alleles and lower heterozygosity at microsatellite loci, as compared to other wolf populations.[99] In 2010, a genetic analysis indicated that a single wolf haplotype (w22) unique to the Apennine Peninsula, and one of the two haplotypes (w24, w25) unique to the Iberian Peninsula, belonged to the same haplogroup as the prehistoric wolves of Europe. Another haplotype (w10) was found to be common to the Iberian peninsula and the Balkans. These three populations with geographic isolation exhibited a near lack of gene flow, and spatially correspond to three glacial refugia.[100]

The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis lupus italicus, however NCBI/Genbank publishes research papers under that name.[101]

Iberian wolf

The Iberian wolf was first recognised as a distinct subspecies (Canis lupus signatus) in 1907 zoologist Ángel Cabrera (naturalist). The wolves of Iberian peninsula have morphologically distinct features from other Eurasian wolves and each are considered by their researchers to represent their own subspecies.[102][103] The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis lupus signatus, however NCBI/Genbank does list it.[104]

Himalayan wolf and Indian gray wolf

| Divergence times | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lineage and divergence times - southern Asian wolves |

The Himalayan wolf is formed by one haplotype[106] that currently falls within the Tibetan wolf (Canis lupus chanco) subspecies, but based on mDNA sequencing has been proposed as a separate species Canis himalayensis.[106][107] The Indian gray wolf is formed by two closely related haplotypes[106]:116 that fall within the Indian wolf (Canis lupus pallipes) subspecies, but based on mDNA sequencing has been proposed as a separate species Canis indica.[106][107] Neither proposal has been endorsed because they relied on a limited number of museum and zoo samples that may not have been representative of the wild population, and a call for further fieldwork has been made.[108] Based on a fossil record estimate that the divergence time between the coyote and the wolf lineages occurred one million years ago and with an assumed wolf mutation rate, one study estimated the time of divergence of the Himalayan wolf and the Indian gray from the wolf/dog ancestor to be 800,000 years and 400,000 years ago respectively.[107] Another study, which expressed some concerns with the earlier study, gave an estimate of 630,000 ago years and 270,000 ago years respectively.[106] During Pleistocene glaciations these wolf lineages were isolated in refuges.[107] In 2007, a study found that the Indian gray wolf was basil to all extant gray wolves and that the Himalayan wolf belonged to a different clade.[109] In 2010, a study found that these two wolves formed a separate clade being 6 mutations distant from the extant gray wolf, which indicated distinct (i.e. different) lineages.[100] In 2012, a limited genetic analysis of the scats of 2 Himalayan wolves from remote and widely separated areas reconfirmed their basal lineage.[110]

The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis himalayensis nor Canis indica, however NCBI/Genbank lists a new subspecies Canis lupus himalayensis[111] as separate from Canis lupus chanco, and a new subspecies Canis lupus indica[112] as separate from Canis lupus pallipes.

- Further information: Himalayan wolf and Indian gray wolf

Tibetan wolf

In 2009, the Tibetan wolf was found to be genetically distinct enough to propose a separate species.[113][114] In 2011, another genetic study found that the Tibetan wolf might be an archaic pedigree within the wolf subspecies, however the study defined Canis lupus laniger as the Tibetan wolf distinct from Canis lupus chanco the Mongolian wolf.[115] In 2013, a major genetic study of dogs and wolves included the DNA sequences of 2 Tibetan wolves but then "excluded two aberrant modern wolf sequences from this analysis since their phylogenetic positioning suggests only a distant relationship to all extant gray wolves and their taxonomic classification as a member of Canis lupus or a separate sub-species is a matter of debate."[116]:Sup The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis lupus laniger, however NCBI/Genbank lists it[117] as the Tibetan wolf, and separately Canis lupus chanco [118] as the Mongolian wolf.

North America

Coastal wolves

A study of the three coastal wolves indicated a close phylogenetic relationship across regions that are geographically and ecologically contiguous, and the study proposed that Canis lupus ligoni (Alexander Archipelago wolf), Canis lupus columbianus (British Columbia wolf), and Canis lupus crassodon (Vancouver Island wolf) should be recognized as a single subspecies of Canis lupus.[119] They share the same habitat and prey species, and form one study's 6 identified North American ecotypes - a genetically and ecologically distinct population separated from other populations by their different type of habitat.[120][121]

Eastern wolf

The eastern wolf has two proposals over its origin. One is that the eastern wolf is a distinct species (C. lycaon) that evolved in North America, as opposed to the gray wolf that evolved in the Old World, and is related to the red wolf. The other is that it is derived from admixture between gray wolves which inhabited the Great Lakes area and coyotes, forming a hybrid that was classified as a distinct species by mistake.[122] The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis lycaon, however NCBI/Genbank lists it.[123]

Red wolf

The red wolf is an enigmatic taxon of which there are two proposals over its origin. One is that the red wolf was a distinct species (C. rufus) that has undergone human-influenced admixture with coyotes. The other is that it was never a distinct species but was derived from admixture between coyotes and gray wolves, due to the gray wolf population being eliminated by humans.[122] The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis rufus, however NCBI/Genbank lists it.[124]

See also

References

- 1 2 Mech, L.D., Boitani, L. (2008). "Canis lupus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ Linnæus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10 ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. pp. 39–40. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ↑ Linnæus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10 ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. pp. 39–40. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- 1 2 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 Smithsonian - Animal Species of the World database. "Canis lupus".

- ↑ Mech, L. David (1981). The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, p. 354, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- ↑ Nowak, R. M. (1995). Another look at wolf taxonomy. pp. 375-397 in L. N. Carbyn, S. H. Fritts and D. R. Seip (eds), Ecology and conservation of wolves in a changing world: proceedings of the second North American symposium on wolves, Edmonton, Canada.

- ↑ Mech & Boitani 2003, pp. 246

- ↑ Young & Goldman 1944b, pp. 413–477

- ↑ The mammals of North America, E. Raymond Hall & Keith R. Kelson, Ronald Press New York, 1959

- ↑ Mech, L. David. 1970. The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

- ↑ The mammals of North America, E. Raymond Hall, Wiley New York, 1981

- ↑ Nowak, Ronald M., and N. E. Federoff. 1996. Systematics of wolves in eastern North America. Defenders of Wildlife, Wolves of America Conference Proceedings, Albany, NY, pp. 187-203.

- ↑ Wilson, P. J.; Grewal, S.; Lawford, I. D.; Heal, J. N. M.; Granacki, A. G.; Pennock, D.; Theberge, J. B.; Theberge, M. T.; Voigt, D. R.; Waddell, W.; Chambers, R. E.; Paquet, P. C.; Goulet, G.; Cluff, D.; White, B. N. (2000). "DNA profiles of the eastern Canadian wolf and the red wolf provide evidence for a common evolutionary history independent of the gray wolf". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 78 (12): 2156–2166. doi:10.1139/cjz-78-12-2156.

- ↑ Chambers, S. M., Fain, S. R., Fazio, B., Amaral, M. (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna. 77: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ↑ National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (January 2014). "Review of Proposed Rule Regarding Status of the Wolf Under the Endangered Species Act" (PDF). University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- 1 2 Joseph W. Hinton, Michael J. Chamberlain, David R. Rabon Jr. (August 2013). "Red Wolf (Canis rufus) Recovery: A Review with Suggestions for Future Research". Animals. 3 (3): 722–724. doi:10.3390/ani3030722. Retrieved 2015-08-16.

- ↑ A Comprehensive Review and Evaluation of the Red Wolf (Canis rufus) Recovery Program (PDF) (Report). Wildlife Management Institute, Inc. November 14, 2014. p. 171. Retrieved 2015-08-16.

- ↑ Rutledge, Linda Y.; Wilson, Paul J.; Klütsch, Cornelya F.C.; Patterson, Brent R.; White, Bradley N. (2012). "Conservation genomics in perspective: A holistic approach to understanding Canis evolution in North America". Biological Conservation. 155: 186–192. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.05.017.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 Fan, Zhenxin; Silva, Pedro; Gronau, Ilan; Wang, Shuoguo; Armero, Aitor Serres; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ramirez, Oscar; Pollinger, John; Galaverni, Marco; Ortega Del-Vecchyo, Diego; Du, Lianming; Zhang, Wenping; Zhang, Zhihe; Xing, Jinchuan; Vilà, Carles; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Godinho, Raquel; Yue, Bisong; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Worldwide patterns of genomic variation and admixture in gray wolves". Genome Research. 26 (2): 163–73. doi:10.1101/gr.197517.115. PMID 26680994.

- ↑ "Canis lupus lupus Linnaeus, 1758". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Heptner, V. G. & Naumov, N., P. (1998) Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc., USA, pp. 184-87, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "Canis lupus albus Kerr, 1792". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- 1 2 Heptner, V. G. & Naumov, N., P. (1998) Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc., USA, pp. 182-184, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "Canis lupus arabs Pocock, 1934". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Lopez, Barry (1978). Of wolves and men. New York: Scribner Classics. p. 320. ISBN 0-7432-4936-4.

- ↑ Fred H. Harrington, Paul C. Paquet (1982). Wolves of the World: Perspectives of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. p. 474. ISBN 0-8155-0905-7.

- 1 2 Heptner, V. G. & Naumov, N., P. (1998) Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc., USA, pp. 188-89, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Heptner, V. G. & Naumov, N., P. (1998) Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc., USA, pp. 191-93, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ↑ Fauna of British India: Mammals Volume 2 by R. I. Pocock, printed by Taylor and Francis, 1941

- ↑ Walker, Brett L. (2005). The Lost Wolves Of Japan. p. 331. ISBN 0-295-98492-9.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Ben Allen (2008). "Home Range, Activity Patterns, and Habitat use of Urban Dingoes" (PDF). 14th Australasian Vertebrate Pest Conference. Invasive Animals CRC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ↑ Fleming, Peter; Laurie Corbett; Robert Harden; Peter Thomson (2001). Managing the Impacts of Dingoes and Other Wild Dogs. Commonwealth of Australia: Bureau of Rural Sciences.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Freedman, Adam H.; Gronau, Ilan; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, Diego; Han, Eunjung; Silva, Pedro M.; Galaverni, Marco; Fan, Zhenxin; Marx, Peter; Lorente-Galdos, Belen; Beale, Holly; Ramirez, Oscar; Hormozdiari, Farhad; Alkan, Can; Vilà, Carles; Squire, Kevin; Geffen, Eli; Kusak, Josip; Boyko, Adam R.; Parker, Heidi G.; Lee, Clarence; Tadigotla, Vasisht; Siepel, Adam; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Harkins, Timothy T.; Nelson, Stanley F.; Ostrander, Elaine A.; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Wayne, Robert K.; et al. (2014). "Genome Sequencing Highlights the Dynamic Early History of Dogs". PLoS Genetics. 10 (1): e1004016. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016. PMC 3894170

. PMID 24453982.

. PMID 24453982. - ↑ Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V. J.; Sawyer, S. K.; Greenfield, D. L.; Germonpre, M. B.; Sablin, M. V.; Lopez-Giraldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; Napierala, H.; Uerpmann, H.-P.; Loponte, D. M.; Acosta, A. A.; Giemsch, L.; Schmitz, R. W.; Worthington, B.; Buikstra, J. E.; Druzhkova, A.; Graphodatsky, A. S.; Ovodov, N. D.; Wahlberg, N.; Freedman, A. H.; Schweizer, R. M.; Koepfli, K.- P.; Leonard, J. A.; Meyer, M.; Krause, J.; Paabo, S.; et al. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (6160): 871. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726.

- ↑ Spady TC, Ostrander EA (January 2008). "Canine Behavioral Genetics: Pointing Out the Phenotypes and Herding up the Genes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 10–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.001. PMC 2253978

. PMID 18179880.

. PMID 18179880. - ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Ishiguro, Naotaka; Inoshima, Yasuo; Shigehara, Nobuo; Ichikawa, Hideo; Kato, Masaru (2010). "Osteological and Genetic Analysis of the Extinct Ezo Wolf (Canis Lupus Hattai) from Hokkaido Island, Japan". Zoological Science. 27 (4): 320–4. doi:10.2108/zsj.27.320. PMID 20377350.

- ↑ Nowak, R.M. 1995. Another look at wolf taxonomy. Pages 375-397 in L.H. Carbyn, S.H. Fritts, D.R. Seip, editors. Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World. Canadian Circumpolar Institute, Edmonton, Canada. (Refer to page 396)

- 1 2 3 Walker, Brett (2008). The Lost Wolves of Japan. University of Washington Press.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Shigehara N, Hongo H (2000) Dog and wolf remains of the earliest Jomon period at Torihama site in Fukui Prefecture. Torihama-Kaizuka-Kennkyu 2: 23–40 (in Japanese)

- ↑ Ishiguro, Naotaka; Inoshima, Yasuo; Shigehara, Nobuo (2009). "Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of the Japanese Wolf (Canis Lupus Hodophilax Temminck, 1839) and Comparison with Representative Wolf and Domestic Dog Haplotypes". Zoological Science. 26 (11): 765–70. doi:10.2108/zsj.26.765. PMID 19877836.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ NATURAL HISTORY OF THE MAMMALIA OF INDIA AND CEYLON by Robert A. Sterndale, THACKER, SPINK, AND CO. BOMBAY: THACKER AND CO., LIMITED. LONDON: W. THACKER AND CO. 1884.

- ↑ A monograph of the canidae by St. George Mivart, F.R.S, published by Alere Flammam. 1890

- ↑ "Canis lupus alces Goldman, 1941". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 422-24

- ↑ "Canis lupus arctos Pocock, 1935". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 430-31

- ↑ "Canis lupus baileyi Nelson and Goldman, 1929". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 469-71

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 435-36

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 472-74

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 459-60

- ↑ "The Wolf", Alsatian Shepalute's: A New Breed for a New Millennium by Lois Denny, AuthorHouse, 2004, Pg. 42

- ↑ Klinkenberg, Jeff, "For saving the Florida panther, it's desperation time", St. Petersburg Times, February 11, 1990

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 455-8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Wolves of North America", E. A. Goldman, Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Feb., 1937), pp. 37–45

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 427-29

- ↑ "Canis lupus irremotus Goldman, 1937". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 445-49

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 434-35

- ↑ "Wolf in Newfoundland probably made it to island on ice, experts say". The Telegram. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Genetic Retesting of DNA Confirms Second Wolf on Island of Newfoundland". Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 453-55

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 437-41

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 474-76

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 476-77

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 463-66

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 466-68

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 441-45

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 424-27

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Nowak, R.M. 1983. A perspective on the taxonomy of wolves in North America. In: Carbyn, L.N., ed. Wolves in Canada and Alaska. Canadian Wildlife Service, Report Series 45:lO-19.

- ↑ Giraud, D. E. (1905), A check list of mammals of the North American continent, the West Indies and the neighboring seas, Chicago, p. 374

- ↑ Mech, L. David (1981), The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 352-353, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- ↑ "Red Wolf" (PDF). canids.org.

- ↑ Red Wolf Recovery Project from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services

- ↑ Mech, L. David (1981), The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, p. 353, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- ↑ Miller, G. S. (1913). "The names of the large wolves of northern and western North America". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 59 (15).

- ↑ Glover, A. (1942), Extinct and vanishing mammals of the western hemisphere, with the marine species of all the oceans, American Committee for International Wild Life Protection, pp. 227-229.

- ↑ (Italian) Altobello, G. (1921), Fauna dell'Abruzzo e del Molise. Mammiferi. IV. I Carnivori (Carnivora), Colitti e Figlio, Campobasso, pp. 38-45

- 1 2 Nowak, R. M. & Federoff, N. E. (2002), The systematic status of the Italian wolf Canis lupus, Acta Theriologica 47(3): 333-338

- ↑ Wayne, R. K.; Lehman, N.; Allard, M. W.; Honeycutt, R. L. (1992). "Mitochondrial DNA Variability of the Gray Wolf: Genetic Consequences of Population Decline and Habitat Fragmentation". Conservation Biology. 6 (4): 559–569. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.06040559.x.

- ↑ Randi, E.; Lucchini, V.; Christensen, M. F.; Mucci, N.; Funk, S. M.; Dolf, G.; Loeschcke, V. (2000). "Mitochondrial DNA Variability in Italian and East European Wolves: Detecting the Consequences of Small Population Size and Hybridization". Conservation Biology. 14 (2): 464–473. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.98280.x.

- ↑ V. LUCCHINI, A. GALOV and E. RANDI Evidence of genetic distinction and long-term population decline in wolves (Canis lupus) in the Italian Apennines. Molecular Ecology (2004) 13, 523–536. abstract online

- 1 2 Pilot, M.; et al. (2010). "Phylogeographic history of grey wolves in Europe". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 104. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-104. PMC 2873414

. PMID 20409299.

. PMID 20409299. - ↑ "NCBI search Canis lupus italicus".

- ↑ The wolf in Spain

- ↑ Vos, J. (2000). "Food habits and livestock depredation of two Iberian wolf packs (Canis lupus signatus) in the north of Portugal". Journal of Zoology. 251 (4): 457. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00801.x.

- ↑ "Canis lupus signatus".

- 1 2 3 Koepfli, K.-P.; Pollinger, J.; Godinho, R.; Robinson, J.; Lea, A.; Hendricks, S.; Schweizer, R. M.; Thalmann, O.; Silva, P.; Fan, Z.; Yurchenko, A. A.; Dobrynin, P.; Makunin, A.; Cahill, J. A.; Shapiro, B.; Álvares, F.; Brito, J. C.; Geffen, E.; Leonard, J. A.; Helgen, K. M.; Johnson, W. E.; O’Brien, S. J.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; Wayne, R. K. (2015-08-17). "Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species". Current Biology. 25: 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Aggarwal, R. K.; Kivisild, T.; Ramadevi, J.; Singh, L. (2007). "Mitochondrial DNA coding region sequences support the phylogenetic distinction of two Indian wolf species". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 45 (2): 163–172. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2006.00400.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Sharma, D. K.; Maldonado, J. E.; Jhala, Y. V.; Fleischer, R. C. (2004). "Ancient wolf lineages in India". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (Suppl 3): S1–S4. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0071. PMC 1809981

. PMID 15101402.

. PMID 15101402. - ↑ Shrotriya, S., Lyngdoh, S., Habib, B. (2012). "Wolves in Trans-Himalayas: 165 years of taxonomic confusion" (PDF). Current Science. 103 (8). Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ Leonard, J. A.; Vilà, C; Fox-Dobbs, K; Koch, P. L.; Wayne, R. K.; Van Valkenburgh, B (2007). "Megafaunal extinctions and the disappearance of a specialized wolf ecomorph" (PDF). Current Biology. 17 (13): 1146–50. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.072. PMID 17583509.

- ↑ Subba, S.A. (2012). "Assessing the genetic status, distribution, prey selection and conservation issues of Himalayan wolf (Canis himalayensis) in Trans-Himalayan Dolpa, Nepal" (PDF). The Rufford Small Grants Foundation.

- ↑ "Canis lupus himalayensis". NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Institutes of Health.

- ↑ "Canis lupus indica".

- ↑ Meng, Chao; Zhang, Honghai; Meng, Qingcheng (2009). "Mitochondrial genome of the Tibetan wolf". Mitochondrial DNA. 20 (2–3): 61–3. doi:10.1080/19401730902852968. PMID 19347764.

- ↑ Zhao, C; Zhang, H; Zhang, J; Chen, L; Sha, W; Yang, X; Liu, G (2014). "The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the Tibetan wolf (Canis lupus laniger)". Mitochondrial DNA. 27: 1. doi:10.3109/19401736.2013.865181. PMID 24438245.

- ↑ Zhang, Honghai; Chen, Lei (2010). "The complete mitochondrial genome of dhole Cuon alpinus: Phylogenetic analysis and dating evolutionary divergence within canidae". Molecular Biology Reports. 38 (3): 1651–60. doi:10.1007/s11033-010-0276-y. PMID 20859694.

- ↑ Thalmann, O. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. AAAS. 342 (6160): 871–874. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726.

- ↑ "Canis lupus laniger".

- ↑ "Canis lupus chanco".

- ↑ Weckworth, Byron V.; Dawson, Natalie G.; Talbot, Sandra L.; Flamme, Melanie J.; Cook, Joseph A. (2011). "Going Coastal: Shared Evolutionary History between Coastal British Columbia and Southeast Alaska Wolves (Canis lupus)". PLoS ONE. 6 (5): e19582. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019582. PMID 21573241.

- ↑ Schweizer, Rena M.; Vonholdt, Bridgett M.; Harrigan, Ryan; Knowles, James C.; Musiani, Marco; Coltman, David; Novembre, John; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Genetic subdivision and candidate genes under selection in North American grey wolves". Molecular Ecology. 25 (1): 380–402. doi:10.1111/mec.13364. PMID 26333947.

- ↑ Schweizer, Rena M.; Robinson, Jacqueline; Harrigan, Ryan; Silva, Pedro; Galverni, Marco; Musiani, Marco; Green, Richard E.; Novembre, John; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Targeted capture and resequencing of 1040 genes reveal environmentally driven functional variation in grey wolves". Molecular Ecology. 25 (1): 357–79. doi:10.1111/mec.13467. PMID 26562361.

- 1 2 Wayne, Robert K.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2016). "Hybridization and endangered species protection in the molecular era". Molecular Ecology. 25 (11): 2680. doi:10.1111/mec.13642. PMID 27064931.

- ↑ "Canis lycaon".

- ↑ "Canis rufus".

External links

- Canis lupus on the ITIS (Integrated Taxonomic Information System)

- Citations for Mammal Species of the World, as a PDF

- Ancient origin and evolution of the Indian wolf including discussion on naming.

- Animal Corner, information on wolves