Sprota

Sprota was the name of a Breton captive who William I, Duke of Normandy took as a wife in the Viking fashion (more danico)[1][2] and by her had a son, Richard I, Duke of Normandy. After the death of her husband William, she became the wife of Esperleng and mother of Rodulf of Ivry.[3][4][5]

Life

The first mention of her is by Flodoard of Reims and although he doesn't name her he identifies her under the year [943] as the mother of "William’s son [Richard] born of a Breton concubine".[6] Her Breton origins could mean she was of Celtic, Scandinavian, or Frankish origin, the latter being the most likely based on her name spelling.[7] Elisabeth van Houts wrote "on this reference rests the identification of Sprota, William Longsword’s wife 'according to the Danish custom', as of Breton origin".[8] The first to provide her name was William of Jumièges.[9][10] The irregular nature (as per the Church) of her relationship with William served as the basis for her son by him being the subject of ridicule, the French King Louis "abused the boy with bitter insults", calling him "the son of a whore who had seduced another woman's husband."[11][12]

At the time of the birth of her first son Richard, she was living in her own household at Bayeux, under William's protection.[4] William, having just quashed a rebellion at Pré-de Bataille (c.936),[lower-alpha 1] received the news by a messenger that Sprota had just given birth to a son; delighted at the news William ordered his son to be baptized and given the personal name of Richard.[10] William's steward Boto became the boy's godfather.[13]

After the death of William Longsword and the captivity of her son Richard, she had been 'collected' from her dangerous situation by the 'immensely wealthy' Esperleng.[3] Robert of Torigni identified Sprota's second husband[lower-alpha 2] as Esperleng, a wealthy landowner who operated mills at Pîtres.[4][14]

Family

By William I Longsword she was the mother of:

By Esperling of Vaudreuil she was the mother of:

- Rodulf, Count of Ivry[16]

- several daughters who married Norman magnates

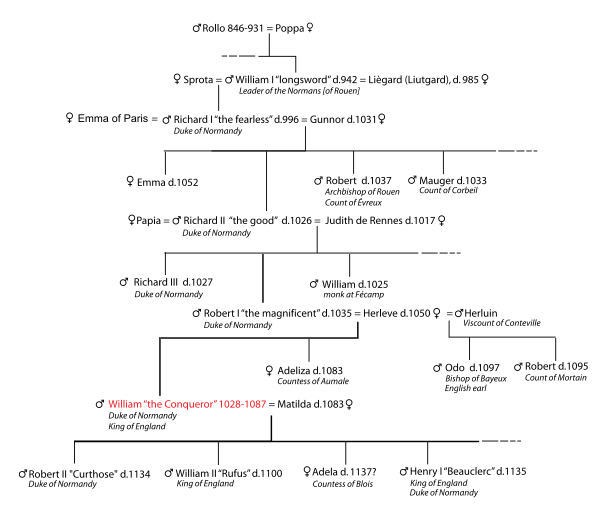

Genealogy

References

- ↑ The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth M.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), p. xxxviii

- ↑ Philip Lyndon Reynolds, Marriage in the Western Church (Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill, 1994), p. 111

- 1 2 Delphine Lemaître Philippe, La Normandie an xe siècle, suivie des Recherches sur les droits des rois de France au patronage d'Illeville (A. Perone, Rouen, 1845) p. 6

- 1 2 3 David Crouch, The Normans: The History of a Dynasty, (Hambledon Continuum, 2007), p. 26

- ↑ The Normans in Europe, ed. & trans. Elisabeth van Houts (Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 4

- ↑ The Annals of Flodoard of Reims, 916-966, ed. & trans. Steven Fanning and Bernard S. Bachrach (University of Toronto Press, 2011), p. 37

- ↑ The Normans in Europe, ed. & trans. Elisabeth van Houts (Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 182

- ↑ The Normans in Europe, ed. & trans. Elisabeth van Houts (Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 47 n. 77

- ↑ K.S.B. Keats-Rohan, 'Poppa of Bayeux and Her Family', The American Genealogist, vol. 72 (July–October 1997), p. 192

- 1 2 The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumieges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth M.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), pp. 78-9

- ↑ The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumieges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth M.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), pp. 102-3 n. 5

- ↑ Emily Albu, The Normans in their histories: propaganda, myth and subversion, (Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2001), p. 69.

- ↑ The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumieges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth M.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), pp. 78-9 n. 3

- ↑ Eleanor Searle, Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840-1066 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988), p. 108

- ↑ Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue Folge, Band II: Die Ausserdeutschen Staaten Die Regierenden Häuser der Übrigen Staaten Europas(Marburg, Germany: Verlag von J. A. Stargardt, 1984), Tafel 79

- ↑ Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue folge, Band III Teilband 4, Das Feudale Frankreich und Sien Einfluss auf des Mittelalters (Marburg, Germany: Verlag von J. A. Stargardt, 1989) Tafel 694A

Notes

- ↑ The date of the battle and as such Richard's birth is commonly given as c.936 but according to the Annals of Jumièges (ed. Laporte, p. 53) Richard was baptized in 938. See The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis, and Robert of Torigni, Ed. & Trans. Elizabeth M.C. Van Houts, Vol. I (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992), pp. 78-9 n. 5.

- ↑ Probably also in the Viking or Danish fashion of marriage. See: Eleanor Searle, Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840-1066 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988), p. 291 n. 2