Sphaeroceridae

- "Lesser dung fly" redirects here. This can also refer to the distantly related fly species Sepsis fulgens.

| Sphaeroceridae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Copromyza equina of the Copromyzinae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Section: | Schizophora |

| Subsection: | Acalyptratae |

| Superfamily: | Sphaeroceroidea |

| Family: | Sphaeroceridae Macquart, 1835 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

Copromyzinae | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Borboridae Newman, 1834 (suppressed) | |

Sphaeroceridae are a family of true flies in the order Diptera, often called small dung flies, lesser dung flies or lesser corpse flies due to their saprophagous habits. They belong to the typical fly suborder Brachycera as can be seen by their short antennae, and more precisely they are members of the section Schizophora. There are over 1,300 species and about 125 genera accepted as valid today, but new taxa are still being described.[1]

Unlike the large "corpse flies" or blow-flies of the family Calliphoridae and the large dung flies of the family Scathophagidae, the small dung flies are members of the schizophoran subsection Acalyptratae. Among their superfamily Sphaeroceroidea, they seem to be particularly close relatives of the family Heleomyzidae.[1]

Description and ecology

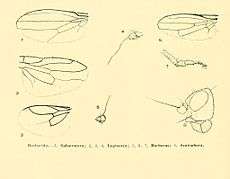

For terms see Morphology of Diptera Dung flies are small to minute, usually dull-colored flies with characteristically thickened first tarsomere of the posterior leg. The first tarsal segment is less than 1+1/2 times as long as the second tarsal segment and dilated. The crossvein separating the 2nd basal and discal cells is missing. Veins 4 and 5 often fade apically. They occur all over the world except in regions with permanent ice-cover. Despite their ubiquity and abundance, little is known about their economic or ecological impact. Some species are known to be parthenogenetic.

Larval stages are poorly known, but those described are slender, narrowed anteriorly, with groups of ventral spicules on creeping welts. The larva is amphipneustic (having only the anterior and posterior pairs of spiracles). The mandibles are simple, hooked, and without additional teeth. The parastomal bars are long, thin structures, fused to the tentoropharyngeal sclerite. The hypopharyngeal sclerites are long separate or connected by a sclerotized bridge; the anterior spiracle (prothoracic spiracle) is a rosette or branched. The posterior spiracles (on the anal segment) are usually on two cylindrical lobes. Each spiracle has three slit or oval openings and three or five groups of interspiracular hairs that are branched in some species.

The larvae are microbial grazers found in abundance in many microenvironments with decomposing organic material. Most species appear to be associated with decaying plants or fungi and they are a part of the nutrient cycle. Some species, especially cave species, are polysaprophagous. Many species are associated with various kinds of faeces including human faeces; there are a few carrion-feeding species. These, however, are extremely abundant and are important components of the carrion-insect community. Sphaerocerids that abound in economically important decomposer communities such as compost and manure, and some decay cycles such as the wrack (seaweed) cycle are mediated by sphaerocerid-dominated insect communities.

As their microbe-associated habits suggest, sphaerocerids may carry many pathogenic microorganisms.[2] Although their reclusive habits preclude a major role in disease transmission; some can present a public health hazard on occasion or act as a warning of one. For instance Leptocera caenosa and other sphaerocerids are associated with blocked sewage drains.[3] Some species occasionally reach high population levels in food-processing plants and other buildings where they may indicate blocked drains, waste accumulation and inadequate hygiene. One species, Poecilosomella angulata, has been implicated in human intestinal myiasis[4] They have been implicated as the major means by which nematodes are disseminated among mushroom houses. Sphaeoceridae often coexist with muscoids especially Fannia canicularis and Musca domestica in the complex manure ecosystem of poultry houses, and other confined-animal facilities. Here the sphaeocerids are prey for mites and beetles, which themselves also feed on the immatures of muscoid flies reducing the population of the more problematic muscoids.[5] Carrion-feeding species are useful post mortem interval indicators in forensic entomology.

Selected genera

The genera are arranged alphabetically according to subfamily; these are arranged in the presumed phylogenetic sequence from the most ancestral to the most advanced:[1] Not all described genera are included in this list.

Subfamily Tucminae Marshall, 1996

- Tucma Mourgués-Schurter, 1987

Subfamily Copromyzinae Stenhammar, 1855

- Alloborborus Duda, 1923

- Borborillus Duda, 1923

- Copromyza Fallén, 1810

- Crumomyia Macquart, 1835

- Lotophila Lioy, 1864

- Norrbomia Papp, 1988

Subfamily Sphaerocerinae Macquart, 1835

- Ischiolepta Lioy, 1864

- Lotobia Lioy, 1864

- Sphaerocera Latreille, 1804

Subfamily Homalomitrinae Roháček & Marshall, 1998

- Homalomitra Borgmeier, 1931

- Sphaeromitra Roháček & Marshall, 1998

Subfamily Limosininae Frey, 1921

|

|

|

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Roháček (2001)

- ↑ Greenberg, B., 1971. Flies and Disease, volume I: Ecology, Classification,and Biotic Association. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

- ↑ Fredeen, F. J. H. & Taylor, M. E. 1964. Borborids (Diptera: Sphaeroceridae) infesting sewage disposal tanks, with notes on the life cycle, behavior and control of Leptocera(Leptocera) caenosa (Rondani). Can. Ent. 96: 801- 808

- ↑ McKibben, J.W. and Micks, D.W. (1956). Report of a case of human intestinal myiasis caused by Leptocera venalicia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 5 (5): 929-32.

- ↑ Axtell, R. C. 1985. Poultry Pests. Chapter 16, p. 269-293, In: Livestock Entomology (Williams et al., editors), Wiley & Sons, New York.

References

- Roháček, Jindřich (ed.) (2001): World Catalogue of Sphaeroceridae. Slezské zemské muzeum, Opava, Czech Republic. ISBN 80-86224-21-X PDF fulltext without images

- K. G. V. Smith, 1989 An introduction to the immature stages of British Flies. Diptera Larvae, with notes on eggs, puparia and pupae.Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects Vol 10 Part 14. pdf download manual (two parts Main text and figures index)

Further reading

Important works on Sphaeroceridae

- Oswald Duda,1938. 57. Sphaeroceridae (Cypselidae). In Lindner, E. (ed.): Die Fliegen der palaearktischen Region Vol.6, 182 pp., E. Schweizerbart.sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart.

- Scientific papers by Theodor Becker

- Hackman, W. 1965. On the genus Copromyza Fall. (Dipt., Sphaeroceridae), with special reference to the Finnish species. Notul. ent. 45 : 33-46.

- Pitkin, B.R. (1988). Lesser dung flies. Diptera: Sphaeroceridae. Handbooks for the Identification of British insects 10(5e). London: Royal Entomological Society. ISBN 0-901546-67-4

- Richards, O.W. (1930). The British species of Sphaeroceridae (Borboridae:Diptera). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 18, 261-345.

- Rohácek, J. (1982-5). A monograph and reclassification of the previous genus Limosina Macquart (Diptera, Sphaeroceridae) of Europe, parts 1 to 4. Beitrage zur Entomologie

- Eugene Seguy. 1934. Cypselidae. Faune de France volume 28, pp. 444–473. virtuelle numérique

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sphaeroceridae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Sphaeroceridae |

- Family description and images

- Page on Sphaeroceridae in houses

- Image Gallery from Dipter.info

- Family Sphaeroceridae at EOL Images

- Picture of Leptocera limosa, a typical sphaerocerid

- Wing venation

Species lists

- European species list

- Nearctic species list

- Australasian/Oceanian species list

- Japanese species list

- World list