Spaceport America

| Spaceport America | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) Spaceport America terminal hangar facility | |||||||||||

| IATA: none – ICAO: none – FAA LID: 9NM9 | |||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Airport type | Private Commercial Spaceport | ||||||||||

| Owner/Operator | New Mexico Spaceport Authority | ||||||||||

| Location | Sierra County, New Mexico | ||||||||||

| Hub for |

Virgin Galactic, UP Aerospace, Payload Specialties | ||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 4,595 ft / 1,401 m | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 32°59′25″N 106°58′11″W / 32.99028°N 106.96972°WCoordinates: 32°59′25″N 106°58′11″W / 32.99028°N 106.96972°W | ||||||||||

| Website |

www | ||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||

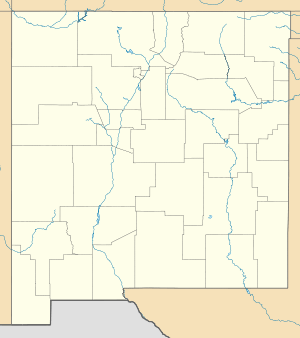

Spaceport America Location within New Mexico | |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Spaceport America is an FAA-licensed spaceport located on 18,000 acres (7,300 hectares) of State Trust Land in the Jornada del Muerto desert basin in New Mexico, United States directly west and adjacent to U.S. Army's White Sands Missile Range. It lies 89 miles (143 km) north of El Paso, 45 miles (72 km) north of Las Cruces, and 20 miles (32 km) southeast of Truth or Consequences.

The site has been described as "the world's first purpose-built commercial spaceport" because it is the first spaceport designed and constructed specifically for commercial users that had not previously been an airport or federal infrastructure of any kind. The site is built to accommodate both vertical and horizontal launch aerospace vehicles, as well as an array of non-aerospace events and commercial activities. Spaceport America is owned and operated by the State of New Mexico, via a state agency, the New Mexico Spaceport Authority.[1][2][3]

Tenants of the spaceport include Virgin Galactic and SpaceX,[4] while UP Aerospace and Armadillo Aerospace have all operated from the spaceport.

The site's major tenants have experienced problems—or change of plans—in development of their programs and technologies, resulting in spaceport revenue far below projections, and a political controversy about what to do with the expensive government-built spaceport. Spaceport America was officially declared open on October 18, 2011.[5] and the site became fully accessible to the general public in June 24, 2015 with a paid tour known as the Spaceport America Experience.

History

Spaceport America is the result of over two decades of efforts to increase the commercial accessibility of spaceflight, come to fruition in southern New Mexico.

Inception

The spaceport's initial concept was proposed by Stanford University engineering lecturer and tech startup advisor Dr. Burton Lee in 1990.[6] He wrote the initial business and strategic plans, secured US$1.4 million in seed funding via congressional earmarks with the help of Senator Pete Domenici, and worked with the New Mexico State University Physical Science Laboratory (PSL) to develop local support for the spaceport concept.

In 1992, the Southwest Space Task Force was formed to advance the New Mexico space industry's commercial infrastructure and activity.[7][8] After several years of study, they focused on a 27-square-mile (70 km2) plot of state-owned land, 45 miles (72 km) north of Las Cruces, as a location for the spaceport.

In 2003, the task force petitioned new Economic Development Cabinet Secretary Rick Homans who then picked up the torch. Homans presented the idea to state Governor Richardson and negotiated with the X Prize Foundation to locate the X Prize Cup in New Mexico. Following an announcement by Governor Richardson and Sir Richard Branson that the new Virgin Galactic would make New Mexico its world headquarters, the state legislature enacted laws providing for the world’s first purpose-built commercial spaceport in 2006.[1][8] The spaceport was branded Spaceport America.

Construction

Construction of the first temporary launch facility at the spaceport site began on 4 April 2006.[9] Early operations of the spaceport utilized this temporary infrastructure, some of it borrowed from neighboring White Sands Missile Range.[10]

In early 2007, red tape was still in the process of being cleared and the spaceport itself was still little more than "a 100-foot (30 m) by 25-foot (7.6 m) concrete slab." That slab would eventually be part of the launch facility for the spaceport's first tenant UP Aerospace.[11] On April 3, voters in neighboring Doña Ana County approved a spaceport tax that would go into effect upon final approval from the Spaceport America host county Sierra County.[12]

The first images of the then planned spaceport's Hangar Terminal Facility (HTF) were released in early September 2007.[13]

In April 2008, the voters in Sierra County approved the plan, releasing over US$40 million in funding for the spaceport.[14] Voters in the third county of Otero, however, rejected the spaceport tax during November general elections. In spite of this, Spaceport America had what it needed to move forward and great headway towards its completion began.[15][16][17]

In December 2008, the New Mexico Spaceport Authority received its launch license for vertical and horizontal launch from the Federal Aviation Administration's Office of Commercial Space Transportation.[18][19] Shortly thereafter, Virgin Galactic signed a 20-year (240-month) lease as the anchor tenant, agreeing to pay US$1 million per year for the first five years in addition to payments on a tiered scale based on the number of launches the company makes.[16][20][21][22]

In December, Gerald Martin Construction Management, from Albuquerque, was chosen to oversee construction.[23][24] As of April 2009, the first of 13 bid packages for the spaceport was expected to be publicly released later that month and all 13 bid packages were scheduled to be released by June 2009. "The goal is to have [construction] completed in 17 months, by December 2010."[25]

The ground-breaking ceremony took place 19 June 2009 and paid tours of the facilities began in December of the same year.[26][27]

By February 2010, the in mid-construction budgetary estimate for completion was $198 million.[28]

On October 22, a ceremonial flypass of Spaceport America was made by SpaceShipTwo to celebrate the completion of the runway.[29]

By October 2010, with the runway complete and the terminal building under active construction, the budgetary estimate for completion increased to $212 million. Approximately two-thirds of that were provided by the state of New Mexico and the remainder from "construction bonds backed by a tax approved by voters in Doña Ana and Sierra counties."[30]

As of August 2012, Spaceport America is substantially complete and the cost of the entire project was $209 million.[31]

Increased private funding

With the beginning of the administration of New Mexico Governor Susana Martinez in 2011, the state government took a new approach to increase private investment to complete the spaceport project. In order to oversee the new effort, Governor Martinez appointed an entirely new board of directors for the Spaceport Authority[32] and removed Executive Director Rick Homans.[33]

By 2013, the Spaceport had signed SpaceX as an additional tenant for vertical takeoff and vertical landing flight testing of prototype reusable rockets such as the Falcon 9 Reusable Development Vehicle. As of 2015 those test flights have not begun.

In February 2015, a bill was introduced into the New Mexico Legislature that the State of New Mexico sell the public spaceport to commercial interests, in order to begin to recoup some of the state's investment in the still-empty project. As of 21 February 2015, the bill had moved onto the Senate Finance Committee.[34]

Delays in operation of the anchor tenant

There have been a series of delays in Virgin Galactic beginning flight operations at Spaceport America. The multi-year extension of the test program and the re-designed engine announced in May 2014 were responsible for much of the delay. In 2014, the spaceport announced that it was seeking additional tenants and hoped to sign another one in the next year.[35]

Budgetary difficulties in operating the spaceport have become salient in New Mexico politics. The annual cost of providing fire protection services that have been contracted for the mostly unused spaceport is approximately US$2.9 million.[36]

The inflight breakup and crash of the first SpaceShipTwo vehicle—VSS Enterprise—in October 2014 has raised questions about the future of the spaceport. With further delays to the start of Virgin Galactic commercial operations, ostensibly to at least 2016, the spaceport may need funding from state or local authorities in New Mexico in order to keep the basic fire and security and administrative operation underway.[37] The Spaceport Authority asked the New Mexico legislature in November 2014 for US$1.7 million in emergency funds to maintain operations until 2016, the earliest date at which Virgin is expected to be able to begin commercial flight operations.[38]

SpaceX has also been delayed in initiating test flights of F9R Dev2 at the spaceport from when they were originally anticipated.

In May 2015, budgetary details made public revealed that the substantially unused spaceport has an annual deficit that has been running approximately US$500,000, with the deficit being made up by state taxpayers. The primary planned revenue in the times of delayed operations by Virgin Galactic and SpaceX, with limited operations by other minor tenants, is local tax revenue, paid by the taxpayers of Sierra and Dona Ana counties.[36]

Facility

.jpg)

The site area nets approximately 670,000 sq ft (62,000 m2), with the terminal & hangar facility grossing an area of 110,152 sq ft (10,233.5 m2).[39]

The western zone of the Facility (25,597 sq ft.) houses support and administrative facilities for Virgin Galactic and the New Mexico Spaceport Authority. The central zone contains the double-height hangar (47,000 sq ft.) to store White Knight Two and SpaceShipTwo crafts. The eastern zone (29,419 sq ft.) encompasses the principal operational training area, departure lounge, spacesuit dressing rooms, and celebration areas.[39]

The onsite restaurant and mission control room have direct east views across the apron, runway and landscape beyond.[39]

The spaceport was built with environmental sustainability in mind. Designed to meet the requirements for LEED Gold Certification, it incorporates "Earth Tubes" to cool the building, solar thermal panels, underfloor radiant cooling and heating, and natural ventilation.[31][39]

A visitor center was planned in downtown Truth Or Consequences (the closest town) to provide shuttle bus services to the Spaceport.[40] However, due to delays in spaceport operations and reduction in spaceport authority revenues, the plans were considerably scaled back in January 2014. Rather than the planned US$20 million facilities, the revised plan in January 2014 had only a US$7.5 million capital budget. Rather than the "planned $13 million visitor center at the spaceport [there will be a] $1.5 million hangar" and the Truth or Consequences visitor center budget request was cut to US$6 million from the original US$7 million.[41] By May 2015, news media were reporting that the spaceport authority "spent so much money with a company to design the visitors’ experience that it had no money left over to actually build the facilities for it."[36]

The spaceport is located under FAA Special Use Airspace Restricted Areas 5111A and 5111B. When both these areas are active the airspace is restricted from surface to 'unlimited'.[42]

Commercial spaceflight

Commercial spaceflight plans include:

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| SpaceX | suborbital reusable prototype flights |

| Virgin Galactic | suborbital passenger flights |

Operation

As of August 2012, twelve suborbital flights had been successfully launched from Spaceport America,[31] and 21 by November 2014.[4] The primary user is UP Aerospace with 10 launches of SpaceLoft XL sounding rockets from 2006 to 2015 and 5 launches of prototype vehicles from 2007 to 2009.

Spaceport revenue

In order to repay the construction bonds and eventually meet operating expenses from Spaceport operations, the spaceport authority has forecast a number of revenue streams. These include lease payments, takeoff and launch payments, tours, etc.

However, anchor tenant Virgin Galactic had paid only US$2.7 million in facility lease payments as of November 2014, and was projected to pay US$50,000 to 100,000 for each six-passenger flight of SpaceShipTwo once flight operations begin.[4] Due to continued long-term revenue shortfalls, the Spaceport Authority is "working on a business plan that would further expand the search for revenue sources beyond Virgin Galactic ...[targeting] new tenants, including other space ventures, commercial projects, tourism, special events and merchandising."[43]

Spaceport operators

As of late 2014, four entities have operated, or announced plans to operate, from Spaceport America.

Google's Project SkyBender

Google is testing high altitude solar powered drones to deliver Internet at 5G speeds. It's using the runway and dedicated flight controls at the Space Flight Operations Center at Spaceport. It's also leasing a hangar from Virgin Galactic.[44]

UP Aerospace

From the early stages, the spaceport has been host to several vertical launches by UP Aerospace. As the first tenant, it had access to multiple functional vertical takeoff facilities of the then incomplete spaceport.[17] As of 2015, UP Aerospace continues to operate its suborbital flights from the spaceport.[45]

Virgin Galactic

As Spaceport America's anchor tenant, Virgin Galactic is to be given primary access to the 12,000-foot-long (3,700 m) runway, from which it will operate 2 1⁄2 hour commercial suborbital trips. As of February 2011, Virgin Galactic has accepted over 400 reservations and collected $50 million in deposits.[46]

Virgin Galactic's suborbital ship, SpaceShipTwo (SS2), is carried by its mother-craft White Knight Two (WK2) to an altitude of 50,000 feet (15,000 m) before being released on a suborbital trajectory under its own rocket power. Space Ship Two's launches will apex 70 miles (110 km) from the Earth's surface at more than 3,200 km/h (2,000 mph). Customers will take part in 3 days pre-flight preparation, bonding, and training onsite at the spaceport.[47]

As of January 2012, Virgin Galactic planned to directly employ about 150 persons at the spaceport site.[48]

In May 2014 Spaceport America and Virgin Galactic signed an agreement with the Federal Aviation Administration to regulate routine space missions launched from Spaceport America, setting out how they will be integrated into the National Airspace System. Virgin plans to initially fly every six weeks.[4]

Virgin Galactic flight operations at the new spaceport have been delayed several times, and as of November 2014, have not begun nine years after the Virgin project was initiated. An October 2014 in-flight breakup of VSS Enterprise—the first flight article SpaceShipTwo during a test flight at Mojave Air and Space Port in California—has further delayed the start of Virgin suborbital spaceflights from Spaceport America.[4]

In 2013, Virgin Galactic had planned for a 2015 flight to stage Zero G Colony, a music festival featuring Lady Gaga[49] however this never occurred when Virgin did not get to passenger flight operations.

X Prize Foundation

Back in 2005, Spaceport America was expected to be the annual venue for the X Prize Cup suborbital spaceflight competitions, once it was fully operational.[50] That series of competitions never materialized.

SpaceX

In May 2013, SpaceX announced that they had signed a three-year lease for land and facilities at Spaceport America in order to support high-altitude, high-velocity flight testing of the Grasshopper v1.1 reusable launch vehicle (RLV), the second generation of the SpaceX experimental vertical takeoff, vertical landing suborbital technology-demonstrator. SpaceX is using Grasshopper as one element of a multi-element program to develop reusable boosters and second stages.[51] The testing is expected to start in New Mexico only after low-altitude initial flight tests of the Falcon 9 Reusable (F9R) development vehicle—formerly known as Grasshopper v1.1—are accomplished in Texas at the SpaceX Rocket Development and Test Facility.[52]

Prior to May 2013, SpaceX had been planning to do these high-altitude tests at US Government's New Mexico high-altitude flight test facility—White Sands Missile Range—which is located on land adjacent and to the east of Spaceport America.[51]

The Falcon 9 tests at Spaceport America are intended to "be used to find hardware limits, such as how many cycles can be put on a stage" and are not likely to occur before late 2016.[53]

By May 2014,[54] SpaceX had expended more than US$2 million on construction of the facility, which includes a landing pad, propellant tanks and a mission control center.[35] SpaceX is using more than 20 local firms to work on the new facility. Work items have included modifying the Range Operations Plan as well as a variety of fire-prevention measures.[54] While the first test flight had been expected to occur sometime in 2014,[55] reports in October 2014 indicated that the first flight of F9R Dev2 at Spaceport America would occur no earlier than the first half of 2015,[56] and the January 2015 Spaceport America newsletter also indicated the plan was for the first flight to occur in the spring of 2015.[57]

In March 2015, plans surfaced—due to the progress made with the atmospheric-descent test program—that SpaceX may skip the previously-planned option of using a new production rocket core as the F9R Dev2 purpose-built test vehicle and instead use the first recovered core from the Falcon 9 ocean booster landing tests. The next possibility for a test flight that might recover a booster core is the CRS-6 mission for NASA, aiming for a 2Q2015 launch.[53] By August 2015, SpaceX had moved some of their equipment from the Spaceport America pad and returned it to their McGregor, Texas test facility. SpaceX is, however, maintaining the lease on the pad for possible future launches.[45]

See also

References

- 1 2 David, Leonard (2007-09-04). "Spaceport America: First Looks at a New Space Terminal". space.com. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Simon Hancock and Alan Moloney (20 June 2009). "Work starts on New Mexico spaceport". BBC. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ↑ Ohtake, Miyoko (August 25, 2007). "Virgin Galactic Preps for Liftoff at World's First Commercial Spaceport". Wired Magazine (15:10). Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ortegon, Josie (2014-11-04). "Special Report: What does Virgin Galactic crash mean for Spaceport America?". KVIA.com. ABC-7. Retrieved 2014-11-08.

- ↑ "Branson Dedicates Space Terminal". Wallstreet Journal. 18 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-18.

- ↑ "History of Spaceport America" (PDF). New Mexico State University. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ Hill, Karl (2006). "Destination: Space-Not even the sky's the limit for new aerospace industry". New Mexico State University. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- 1 2 "Spaceport America: History". New Mexico Spaceport Authority. 2007. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ Haussamen, Heath (2006-04-04). "Temporary spaceport being built; 1st launch likely 'before September'". Las Cruces Sun-News. p. 1A.

- ↑ Holston, Mike (2007-04-28). "Spaceport America interview" (wma video). UP Aerospace. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ↑ Caldwell, Alicia (2007-04-28). "Ashes of Star Trek's Scotty Fly to Space". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ↑ Alba, Diana M. (2007-12-12). "New tax still up in the air". Las Cruces Sun-News. ISSN 1081-2172. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ "First images of Spaceport America revealed". Flight Global. 2007-04-09. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Kaufman, Marc (2008-05-10). "New Mexico Moves Ahead on Spaceport: 2010 Opening Appears to Be Within Reach, Even With Remaining Hurdles". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ↑ Medina, Jose L. (2008-11-06). "Spaceport to move forward despite Otero vote". Las Cruces Sun-News. ISSN 1081-2172. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- 1 2 Spaceport America, New Mexico Spaceport Authority (December 2008). "Spaceport Progress 2008 / 2009". Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- 1 2 "Spaceport America Construction Status". May 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "Spaceport receives launch license". Las Cruces Sun-News. 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ "FAA Issues Launch Site Operator License for Spaceport America" (Press release). New Mexico Spaceport Authority. 2008-12-15. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ "America Spaceport Grows Desert". Fox News. 2010-01-28. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Alba, Diana M. (2009-01-01). "Virgin Galactic signs Spaceport America lease". Las Cruces Sun-News. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ↑ "Governor Bill Richardson Announces Spaceport America and Virgin Galactic Sign Historic Lease Agreement" (Press release). New Mexico Spaceport Authority. 2008-12-31. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ↑ Meeks, Ashley (2008-12-19). "Company chosen to build spaceport". Las Cruces Sun-News. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ↑ "Construction Management Firm Named for Spaceport America" (Press release). New Mexico Spaceport Authority. 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ↑ Ramirez, Steve (2009-04-10). "Spaceport America offers job opportunities". Las Cruces Sun-News. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- ↑ "Tours of spaceport site in December". Las Cruces Sun-News. 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ↑ "Spaceport America Hardhat Tours Announced at ISPCS" (PDF) (Press release). Spaceport America. October 21, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ↑ Barry, Dan (February 21, 2010). "A New Exit to Space Readies for Business". New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Virgin spaceship to pass new milestone". AFP via Yahoo News. 2010-10-22. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ↑ Roberts, Chris (2010-10-23). "New era draws closer: Spaceport dedicates runway on New Mexico ranch". El Paso Times. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

two-thirds of the $212 million required to build the spaceport came from the state of New Mexico... The rest came from construction bonds backed by a tax approved by voters in Doña Ana and Sierra counties.

- 1 2 3 Polland, Jennifer (2012-08-30). "See Where The World's First Commercial Space Flights Will Take Off From". Business Insider. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ "Martinez pushes private funds for spaceport". Cibola Beacon. 2011-02-14. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

Martinez said ... "New Mexico's taxpayers have made a significant investment in the Spaceport project. It's time to see the project through to completion by bringing in private funding."

- ↑ "Letter of Resignation" (PDF). ispcs.com. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ↑ David, Leonard (21 February 2015). "For Sale Sign? – New Mexico's Spaceport America". Inside Outer Space. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- 1 2 Foust, Jeff (2014-10-24). "Spaceport America Seeks To Diversify Customer Base and Revenue Streams". Space News. Retrieved 2014-10-26.

- 1 2 3 Messier, Doug (2015-05-06). "Spaceport America Spending Criticized". Parbolic Arc. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2014-11-03). "A spaceport in limbo". The Space Review. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ↑ Dyson, Stuart (2014-11-20). "NM Spaceport executives asking lawmakers for emergency taxpayer funds". KOB4 News. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.spaceportamerica.com/about-us/spaceport-america.html

- ↑ Korte, Tim (2009-06-19). "Ceremony marks New Mexico spaceport launch". Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ↑ Messier, Doug (2014-01-30). "Plans for Spaceport America Visitors Center Scaled Back". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- ↑ "FAA Special Use Airspace". Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (2015-05-06). "Take a Fresh Peek at Virgin Galactic's Next SpaceShipTwo". NBC News. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jan/29/project-skybender-google-drone-tests-internet-spaceport-virgin-galactic

- 1 2 "Spaceport tenant SpaceX moving equipment, but will maintain lease". Las Cruces Sun News. 2015-07-29. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ VSS Enterprise Completes First Manned Glide Flight, Virgin Galactic, 2010-10-10, accessed 2010-12-30.

- ↑ "Spaceport America - White Sands New Mexico". Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ↑ Alba Soular, Diana (2012-01-16). "Virgin Galactic's Butler builds NM operation". Las Cruces Sun-News. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

"In [the Las Cruces] office, we're likely to have about 20 people. And at the spaceport - it's hard to be precise at this point - but in the region of 150 direct jobs. Of course, the contractors we'll take on is a much bigger number."

- ↑ Roy, Jessica (November 6, 2013). "Lady Gaga to Return to Her Homeland With 2015 Outerspace Performance". Time. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ↑ "Private Spaceflight: Shifting into Fast Forward". space.com. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- 1 2 Lindsey, Clark (2013-05-07). "SpaceX to test Grasshopper reusable booster at Spaceport America in NM". NewSpace Watch. Retrieved 2013-05-07. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Grasshopper flies to its highest height to date". Social media information release. SpaceX. 12 October 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

WATCH: Grasshopper flies to its highest height to date - 744 m (2441 ft) into the Texas sky. http://youtu.be/9ZDkItO-0a4 This was the last scheduled test for the Grasshopper rig; next up will be low altitude tests of the Falcon 9 Reusable (F9R) development vehicle in Texas followed by high altitude testing in New Mexico.

- 1 2 Bergin, Chris (2015-03-19). "Spaceport America set for SpaceX reusability testing". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- 1 2 David, Leonard (2014-05-07). "New Mexico's Spaceport America Eyes SpaceX, Virgin Galactic Flights". Inside Outer Space. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- ↑ Businesses prepare for first flight, Las Cruces Bulletin, Alta LeCompte, 11 July 2014, accessed 30 July 2014.

- ↑ Messier, Doug (2014-10-21). "New Mexico Legislators Look into Spaceport America Finances". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 2014-10-23.

- ↑ "Spaceport America Newsletter". Spaceport America. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spaceport America. |

- Official website

- Aerial view of Spaceport America

- Info @ Encyclopedia Astronautica

- National Geographic Megastructures episode on Spaceport America, 45 minutes duration.

- Spaceport news archive from Las Cruces Sun-News

- "Eat My Contrails, Branson!" from SEED magazine

- Officials optimistic, despite delays. First pictures of the emerging SpaceX testing facility