SEPTA

| |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Locale | Delaware Valley | ||

| Transit type | |||

| Number of lines | 196 | ||

| Number of stations | 290 | ||

| Annual ridership | 329,931,400 (2014)[1] | ||

| Chief executive | Jeffrey D. Knueppel | ||

| Headquarters |

1234 Market Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | ||

| Website | SEPTA | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 1965 | ||

| Operator(s) |

SEPTA (one route in Montgomery Co. contracted) | ||

| Reporting marks |

SEPA SPAX | ||

| Number of vehicles | 2,295 | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 450 mi (720 km) | ||

| Track gauge |

4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge 5 ft 2 1⁄4 in (1,581 mm)[2][3] | ||

| |||

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) is a regional public transportation authority[4] that operates various forms of public transit services—bus, subway and elevated rail, commuter rail, light rail and electric trolleybus—that serve 3.9 million people in five counties in and around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. SEPTA also manages construction projects that maintain, replace, and expand infrastructure and rolling stock.

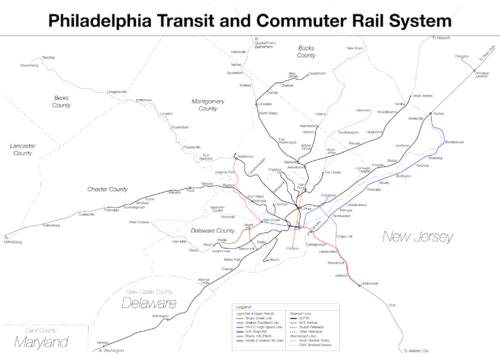

SEPTA is the major transit provider for Philadelphia and its suburbs in Delaware, Montgomery, Bucks and Chester counties. SEPTA is a state created authority and the majority of its board is appointed by the five Pennsylvania counties it serves.[5] While several SEPTA commuter rail lines terminate in the nearby states of Delaware and New Jersey, additional service to Philadelphia from those states is provided by other agencies: the PATCO Speedline from Camden County, New Jersey is run by the Delaware River Port Authority, a bi-state agency, New Jersey Transit operates many bus lines and a commuter rail line to Philadelphia's Center City; and DART First State runs feeder lines to SEPTA stations in the state of Delaware.

SEPTA has the 6th-largest U.S. rapid transit system by ridership, and the 5th largest overall transit system, with about 306.9 million annual unlinked trips. It controls 290 active stations, over 450 miles (720 km) of track, 2,295 revenue vehicles, and 196 routes. SEPTA also manages Shared-Ride services in Philadelphia and ADA services across the region. These services are operated by third-party contractors.

SEPTA is one of only two U.S. transit authorities that operates all of the five major types of terrestrial transit vehicles: regional (commuter) rail trains, "heavy" rapid transit (subway/elevated) trains, light rail vehicles (trolleys), trolleybusses, and motorbusses; the other is Boston's Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, which runs ferryboat service as well.[6]

SEPTA's headquarters are located at 1234 Market Street in Center City, Philadelphia.

History

Formation

SEPTA was created by the Pennsylvania legislature on August 17, 1963, to coordinate government subsidies to various transit and railroad companies in southeastern Pennsylvania. It commenced on February 18, 1964.[7]

On November 1, 1965, SEPTA absorbed two predecessor agencies:

- The Passenger Service Improvement Corporation (PSIC), which was created on January 20, 1960 to work with the Reading Company and Pennsylvania Railroad to improve commuter rail service and help the railroads maintain otherwise unprofitable passenger rail service.

- The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Compact (SEPACT), created on September 8, 1961, by the City of Philadelphia and the Counties of Montgomery, Bucks, and Chester to coordinate regional transport issues.

By 1966, the Reading Company and Pennsylvania Railroad commuter railroad lines were operated under contract to SEPTA. On February 1, 1968, the Pennsylvania Railroad merged with the New York Central railroad to become Penn Central, only to file for bankruptcy on June 21, 1970. Penn Central continued to operate in bankruptcy until 1976, when Conrail took over its assets along with those of several other bankrupt railroads, including the Reading Company. Conrail operated commuter services under contract to SEPTA until January 1, 1983, when SEPTA took over operations and acquired track, rolling stock, and other assets to form the Railroad Division.

Subsequent expansion

Since 1913, a long proposed Roosevelt Boulevard Subway had a similar fate as New York's Second Avenue Subway where many proposals were made, but the project never materialized. Many acquisitions had been made, but only amounted to continuous service cuts through consolidations of competing services of the Reading Railroad and Pennsylvania Railroad. It wasn't until the early 2000s that there was any talk of expansion.

_Bridge_Line_%26_Fare_Tokens.jpg)

On September 30, 1968, SEPTA acquired the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC), which operated a city-wide system of bus, trolley, and trackless trolley routes, the Market–Frankford Line (subway-elevated rail), the Broad Street Line (subway) and the Delaware River Bridge Line (subway-elevated rail to City Hall, Camden, NJ) which became SEPTA's City Transit Division. The PTC had been created in 1940 with the merger of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (formed in 1902) and a group of smaller, then independent transit companies operating within the city and its environs.

On January 30, 1970, SEPTA acquired the Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company, also known as the Red Arrow Lines, which included the Philadelphia and Western Railroad (P&W) route now called the Norristown High Speed Line, the Media and Sharon Hill Lines (Routes 101 and 102) and several suburban bus routes in Delaware County. Today, this is the Victory Division, though it is sometimes referred to as the Red Arrow Division.

On March 1, 1976, SEPTA acquired the transit operations of Schuylkill Valley Lines, which is today the Frontier Division.

Future expansion of SEPTA's commuter rail lines has been discussed since the mid-1980s when the system suffered severe cutbacks. Proposals have been made to restore service to Allentown, Bethlehem, West Chester and Newtown, with support from commuters, local officials and pro-train advocates. The Schuylkill Valley Metro and other plans that would re-establish service to Phoenixville, Pottsville and Reading have also received support.[8] SEPTA has also considered the possibility of a "cross-county metro" that would provide service between the suburban counties without requiring the rider to go into Philadelphia.[9] However, many derelict lines under SEPTA ownership have been converted to rail trails, postponing any restoration proposals for the foreseeable future.[10] Additionally, some, such as Senator Bob Casey, have proposed expanding the Broad Street Line to the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard.[11]

Proposals have also been made for increased service on existing lines, including later evenings and Sundays to Wilmington and Newark in Delaware. Maryland's MARC commuter rail system is considering extending its service as far as Newark Rail Station, which would allow passengers to connect directly between SEPTA and MARC. As of 2014, an expansion of the Norristown High Speed Line is under consideration to extend service to the King of Prussia area.[12]

Governance

SEPTA is governed by a 15-member board of directors:

- The City of Philadelphia appoints two members: one member is appointed by the Mayor, the other by the City Council President. These two board members can veto any item that is approved by the full SEPTA board because the city represents more than two-thirds of SEPTA's local subsidy, fare revenue, and ridership. However, the veto may be overridden with the vote of at least 75% of the full board within 30 days.

- Bucks County, Chester County, Delaware County, and Montgomery County appoint two members each. These members are appointed by the county commissioners in Bucks, Chester, and Montgomery County and by the county council in Delaware County.

- The majority and minority leaders of the two houses of the Pennsylvania State Legislature (the Senate and the House of Representatives) appoint one member each, for a total of four members.

- The governor appoints one member.

The members of the SEPTA Board as of July 2016 are:[13]

- Chairman – Pasquale T. Deon, Sr.

- Vice Chairman – Thomas E. Babcock

- Bucks County – Pasquale T. Deon, Sr. & Charles H. Martin

- Chester County – Kevin L. Johnson, P.E. & William M. McSwain, Esq.

- Delaware County – Thomas E. Babcock & Daniel J. Kubik

- Montgomery County – Kenneth Lawrence, Jr. & Robert D. Fox, Esq.

- Philadelphia County – Beverly Coleman & Clarena I.W. Tolson

- Governor Appointee – Dwight Evans

- Senate Majority Leader Appointee – Stewart Greenleaf, Esq.

- Senate Minority Leader Appointee – William J. Leonard, Esq.

- House Majority Leader Appointee – Michael A. Vereb

- House Minority Leader Appointee – John I. Kane

The day-to-day operations of SEPTA are handled by the general manager, who is appointed and hired by the board of directors. The general manager is assisted by nine department heads called assistant general managers.

The present general manager is Jeffrey Knueppel. Past general managers include Joseph Casey, Faye L. M. Moore, Joseph T. Mack, John "Jack" Leary, Lou Gambaccini, and David L. Gunn. Past acting general managers include James Kilcur and Bill Stead.

Routes and ridership

Rapid transit

- Norristown High Speed Line (Purple Line): formerly known as the Philadelphia & Western (P&W) Railroad and Route 100, this former interurban heavy rail line is powered by third rail and has high level platforms. Daily ridership averaged 8,530 in 2010.[14]

- Market–Frankford Line (Blue Line): subway and elevated line from the Frankford Transportation Center (rebuilt in 2003) in the Frankford section of Philadelphia to 69th Street Transportation Center in Upper Darby, via Center City Philadelphia. Weekday ridership averaged 180,100 in 2010.[14]

- Broad Street Line and Broad–Ridge Spur (Orange Line): subway line along Broad Street in Philadelphia from Fern Rock Transportation Center to AT&T Station/Sports Complex (formerly Pattison Station), via Center City Philadelphia. Weekday ridership averaged 136,670 in 2010.[14]

Trolley and light rail

- Subway–Surface Trolley Lines (Green Line): Five Subway-Surface Trolley Routes—10, 11, 13, 34 and 36 run in a subway in Center City and fan out along on street-level as Surface Trolley Lines in West and Southwest Philadelphia. Daily ridership averaged 79,804 in 2010.[14]

- Routes 101 and 102 (Suburban Trolley Lines): two trolley routes in Delaware County which run mostly on private rights-of-way but also have some street running. Daily ridership averaged 6,546 in 2010.[14]

- Routes 15, 23 and 56: Three surface trolley routes that were suspended in 1992. Routes 23 and 56 are currently operated with buses. Trolley service on Route 15 (the Girard Avenue Line) resumed as of September 2005, operating as a heritage streetcar line. Route 23 has long been SEPTA's most heavily traveled surface route, with daily ridership averaging 21,500 in 2010.[14] The route has now split into Route 23 (northern portion remains) and Route 45 (southern portion).[15]

Trackless trolley (trolleybus)

Trackless trolleys (as they are called by SEPTA) operate on routes 59, 66, and 75. Service resumed in spring 2008 after a nearly five-year suspension.[16] Until June 2002, five SEPTA routes were operated with trackless trolleys, using AM General vehicles built in 1978–79. Routes 29, 59, 66, 75 and 79 used trackless trolleys, but were converted to diesel buses for an indefinite period starting in 2002 (routes 59, 66, 75) and 2003 (routes 29, 79). The aging AM General trackless trolleys were retired and in February 2006, SEPTA placed an order for 38 new low-floor trackless trolleys from New Flyer Industries—enough for routes 59, 66 and 75 only—and the pilot trackless trolley arrived in June 2007, for testing.[17] The vehicles were delivered between February and August 2008. Trackless trolley service resumed on Routes 66 and 75 on April 14, 2008, and on Route 59 the following day, but was initially limited to just one or two vehicles on each route, as new trolley buses gradually replaced the motorbuses serving the routes over a period of several weeks.[18] The SEPTA board voted in October 2006 not to order additional vehicles for Routes 29 and 79, and those routes permanently became non-electric.[16][19]

Bus

SEPTA lists 121 bus routes, not including over 50 school trips, with most routes in the City of Philadelphia proper. SEPTA generally employs lettered, one and two-digit route numbering for its City Division routes, 90-series and 100-series routes for its Victory Division (Chester, Delaware and Montgomery Counties) and its Frontier Division (Montgomery and Bucks Counties), 200-series routes for its Regional Rail connector routes (Routes 201, 204, 205 and 206 in Montgomery & Chester Counties), 300-series routes for other specialized or third-party contract routes and 400-series routes for limited service buses to schools within Philadelphia.

Commuter rail

SEPTA began operating its commuter rail division (as SEPTA Regional Rail) on January 1, 1983. This division operates 13 lines serving more than 150 stations covering most of the five-county southeastern Pennsylvania region. It also runs trains to Wilmington, Newark, Delaware, Trenton, New Jersey and West Trenton, New Jersey. Daily ridership averaged over 121,000 in 2010,[14] with 29% of ridership on the Paoli/Thorndale and Lansdale/Doylestown lines.

Most of the cars used on the lines were built between 1963 and 1976.[20] After building delays, the first Silverliner V cars were introduced into service on October 29, 2010. These cars represent the first new electric multiple units purchased for the Regional Rail system since the completion of the Silverliner IV order in 1976 and the first such purchase to be made by SEPTA.[21] As of March 19, 2013, all Silverliner V cars are in service and make up almost one-third of the current 400 car Regional Rail fleet, which are replacing the older, aging fleet.[22] At the start of July 2016, however, a serious structural flaw (cracks in a weight-bearing beam on a train car's undercarriage) was discovered during an emergency inspection to exist in more than 95% of the 120 Silverliner V cars in the SEPTA regional rail fleet which the company announced would take "the rest of the summer" to repair and would thus would reduce the system's capacity by as much as 50%. In addition to regular commuter rail service the loss of system capacity was also expected to cause transportation issues for the Democratic National Convention being held in Philadelphia on the week of July 25, 2016.[23][24]

Divisions

SEPTA has three major operating divisions: City Transit, Suburban and Regional Rail. These divisions reflect the different transit and railroad operations that SEPTA has assumed.

City Transit Division

The City Transit Division operates routes mostly within the City of Philadelphia, including buses, subway–surface trolleys, surface Trolley Lines, the Market–Frankford Line and the Broad Street Line. SEPTA City Transit Division surface routes include bus and trackless trolley lines. Some city division routes extend into Delaware, Montgomery and Bucks counties. This division is the descendant of the Philadelphia Transportation Company. There are eight operating depots in this division: five of these depots only operate buses, one is a mixed bus/trackless trolley depot, one is a mixed bus/streetcar depot and one is a streetcar-only facility.

Suburban Division

Victory District

The Victory District operates suburban bus and trolley (or light rail) routes that are based at 69th Street Transportation Center in Upper Darby in Delaware County. Its light rail routes comprise the Norristown High Speed Line (Route 100) that runs from 69th Street Transportation Center to Norristown Transportation Center and the SEPTA Surface Media and Sharon Hill Trolley Lines (Routes 101 and 102). This district is the descendant of the Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company, also known as the Red Arrow Lines. Some residents of the Victory District operating area still refer to this district as the "Red Arrow Division."

Frontier District

The Frontier District operates suburban bus routes that are based at the Norristown Transportation Center in Montgomery County and bus lines that serve eastern Bucks County. This district is the descendant of the Schuylkill Valley Lines in the Norristown area and the Trenton-Philadelphia Coach Lines in eastern Bucks County. SEPTA took over Schuylkill Valley Lines operations on March 1, 1976. SEPTA turned over the Bucks County routes (formerly Trenton-Philadelphia Coach Line Routes, a subsidiary of SEPTA) to Frontier Division in November 1983.

Suburban contract operations

Krapf's Coaches operate two bus lines under contract to SEPTA in Chester County. These routes are operated from Krapf's own garage, located in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Krapf's has operated three other bus routes for SEPTA in the past. Route 202 (West Chester to Wilmington), Route 207 (The Whiteland WHIRL) and Route 208 (Strafford Train Station to Chesterbrook) are no longer operating. SEPTA contracted bus operations before in Chester County. SEPTA and Reeder's Inc. joined forces in 1977 to operate three bus routes out of West Chester. These routes were the Route 120 (West Chester to Coatesville), Route 121 (West Chester to Paoli) and Route 122 (West Chester to Oxford). Bus service between West Chester and Coatesville was a replacement for the previous trolley service operated by West Chester Traction. SEPTA did replace two of the routes with their own bus service. Route 122 service was replaced by SEPTA's Route 91 on July 6, 1982 after only one year of service, Route 91 was eliminated due to lack of ridership. Route 121 was replaced by SEPTA's Route 92 on October 11, 1982 and this service continues to operate today. Since ridership on the Route 120 was strong it continued to operate under the operations of Reeder's Inc. even after SEPTA pulled the funding source. Krapf's purchased the Reeder's operation in 1992 and designated the remaining (West Chester to Coatesville) bus route as Krapf's Transit "Route A".

Railroad Division

The Railroad Division[25] operates 13 commuter railroad routes that begin in Central Philadelphia and radiate outwards, terminating in intra-city, suburban and out-of-state locations.

This division is the descendant of the six electrified commuter lines of the Reading Company (RDG), the six electrified commuter lines of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR, later Penn Central: PC) and the new Airport line constructed by the City of Philadelphia between 1974 and 1984.

With the construction and opening of the Center City Commuter Connection Tunnel in 1984, lines were paired such that a former Pennsylvania Railroad line was coupled with a former Reading line. Seven such pairings were created and given route designations numbered R1 through R8 (with R4 not used). As a result, the routes were originally designed so that trains would proceed from one outlying terminal to Center City, stopping at 30th Street Station, Suburban Station and Jefferson Station (formerly Market East Station), then proceed out to the other outlying terminal assigned to the route. Since ridership patterns have changed since the implementation of this plan, SEPTA removed the R-numbers from the lines in July 2010 and instead refers to the lines by the names of their termini.

The out-of-state terminals offer connections with other transit agencies. The Trenton Line offers connections in Trenton, New Jersey to NJ Transit (NJT) or Amtrak for travel to New York City. Plans exist to restore NJT service to West Trenton, New Jersey, thus offering a future alternate to New York via the West Trenton Line and NJT. Another plan offers a connection for travel to Baltimore and Washington DC via MARC, involving extensions of the SEPTA Wilmington/Newark Line from Newark, Delaware, an extension of MARC's Penn service from Perryville, Maryland, or both. It has also been proposed for the line- which currently does not run late nights, nor on Sundays beyond Marcus Hook- to have additional runs at those times to Wilmington and Newark.

Transit police

SEPTA established the current Transit Police Department in 1981. It now has about 260 officers operating in seven patrol zones. It maintains a patrol, bicycle and police dog unit, as well as "Special Operations Response Team" trained to deal with hostage situations.[26]

SEPTA equipment

Buses

In 1982, SEPTA ordered buses from Neoplan USA, a purchase that was both the largest for Neoplan at the time and SEPTA's largest to date. These buses were used throughout the SEPTA service area. SEPTA changed its specifications on new bus orders each year. The Neoplan AK's (numbered 8285–8410), which was SEPTA's first Neoplan order, had longitudinal seating: all of the seats face towards the aisle. However, their suburban counterparts (8411–8434) had longitudinal seating only in the rear of the bus. The back door has a wheelchair ramp, which forced SEPTA officials to limit its use and specify wheelchair lifts in their next order. These buses had a nine-liter 6v92 engine and Allison HT-747 transmission.

In 1983, SEPTA, along with other transit operators in Pennsylvania, ordered 1,000 Neoplan buses of various lengths.[27] SEPTA ultimately received 450 buses from this order: 425 were 40-foot (12 m) buses (BD 8435–8584 and CD 8601–8875), which came without wheelchair lifts, and 25 35-foot (11 m) buses (BP 1301–1325).

SEPTA purchased additional Neoplans in 1986. The first two groups (3000–3131 and 3132–3251) came without rear wheelchair lifts; the last two groups, one in late 1987 (3252–3371) and another in 1989 (3372–3491), included them. All Neoplans built between 1986 and 1989 were equipped with a ZF 4HP-590 transmission.

By the early 1990s, SEPTA had 1,092 Neoplan AN440 coaches in active service, making it the largest transit in North American with a fleet primarily manufactured by Neoplan USA. These buses dominated the streets of Philadelphia through late 1997, when the earlier fleet of AK and BD Neoplans (8285–8581) was replaced by 400 buses built by American Ikarus and – the same company after a 1996 reorganization – North American Bus Industries. The older GMC RTS 35- and 40-foot buses were also replaced in this order, with the sole remaining exception of No. 4462, a 35-foot coach.[28] More replacements occurred when SEPTA received its first low-floor fleet and retired the last An440 buses on June 20, 2008.

The Neoplan model has not entirely vanished from Philadelphia's streets; in 1998, SEPTA ordered 155 articulated buses from the company. These buses replaced the 1984 Volvo 10BM 60-foot articulated buses.[29]

The 1998 purchase also included 80 29-foot Transmark-29 buses from National-Eldorado (4501–4580), the first of which began to arrive in late 2000. Most of these buses are on suburban routes, but some are in the "LUCY" service in the University City section of West Philadelphia, in a special paint scheme, and others on lighter lines within Philadelphia. SEPTA had decided to buy from Metrotrans Legacy, SEPTA's first choice in small buses, but the company filed for bankruptcy in 1999.

A fleet of buses known as "cutaways" were also purchased. These buses were built on Ford van chassis, with bodies similar to those seen on car rental shuttles at various airports. These buses were retired around 2003 and replaced with slightly larger cutaway buses on a Freightliner truck chassis.

After evaluating sample buses from New Flyer and NovaBus in 1994–96, SEPTA ordered 100 low-floor buses (nos. 5401–5500) from New Flyer in 2001.

Trackless trolley (trolley bus) service was suspended in 2003 and the 110 AM General vehicles that had provided service on SEPTA's five trackless trolley routes never returned to service.[30] However, in early 2006 SEPTA ordered 38 new low-floor trackless trolleys from New Flyer, which entered service in 2008, restoring trackless service on routes 59, 66 and 75. These buses replaced SEPTA Neoplan EZs, ending Neoplan's 26-year domination.[18]

SEPTA placed an order with delivery starting in 2008 for 400 New Flyer hybrid buses—with options for up to 80 additional buses to replace the NABI Ikarus buses at the end of their 12-year life.[31] These will not be the first hybrid buses, since SEPTA purchased two small groups of hybrids, 5601H–5612H, which arrived in 2003, and 5831H–5850H in 2004. Before the 2008 purchase, SEPTA borrowed an MTA New York City Transit Orion VII hybrid bus # 6365 to evaluate it in service. SEPTA was the first to purchase New Flyer DE40LFs equipped with rooftop HVAC units.

SEPTA's revenue from advertisements on the backs of its buses leads the authority to order mainly buses equipped with a rooftop HVAC and with their rear route-number sign mounted close to the roof, especially on 2008–2009 New Flyer DE40LFs and future orders.[32]

| Vehicle types | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current Bus Fleet Roster

| Order Year | Manufacturer | Model | Powertrain (Engine/Transmission) |

Propulsion | Fleet Series (Qty.) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | NFI | D40LF |

|

Diesel | 5401-5500 (100) |

|

| ElDorado National | Transmark RE 29' |

|

Diesel | 4501-4580 (80),*4581 (1) |

| |

| 2002 | NFI | DE40LF |

|

Hybrid | 5601H-5612H (12) |

SEPTA's first hybrid buses |

| D40LF |

|

Diesel | 5501-5600 (100) |

|||

| 2003 | D40LF |

|

Diesel | 5613-5712 (100) |

| |

| 2004 | D40LF |

|

Diesel | 5713-5830, 5851-5950 (118) |

| |

| Freightliner/Champion | FB65/Defender |

|

Diesel | 2070-2097 (28) |

||

| NFI | DE40LF |

|

Hybrid | 5831H-5850H (20) |

||

| 2005 | D40LF |

|

Diesel | 8000-8119 (120) |

| |

| 2007 | Chevy/Champion | C4500/Challenger |

|

Diesel | 2098-2099 (2) |

|

| 2007-08 | NFI | E40LFR |

|

Electric | 800, 801-837 (38) | |

| 2008 | DE40LF |

|

Hybrid | 8120-8219 (120) |

| |

| 2009 | DE40LF |

|

Hybrid | 8220-8339 (120) |

||

| 2010 | DE40LFR |

|

Hybrid | 8340-8459 (120) |

||

| 2011 | DE40LFR |

|

Hybrid | 8460-8559 (100) |

| |

| 2013-2016 | NovaBus | LFS-A and/or LFS-A HEV |

|

Hybrid | 7300-7484

(185) |

|

| LFS HEV |

|

Hybrid | 8600-8689' (90) |

|||

| 2016 | NFI | MD30 |

|

Diesel | 4600-4634 (35) |

|

Subway

The Broad Street Line uses cars built by Kawasaki between 1982 and 1984. These cars, known as B-IV as they are the fourth generation used on the line, are stainless steel and include some cars with operating cabs at both ends, as well as some with only a single cab.

The Market-Frankford Line uses a class of car known as M-4, as they, like the Broad Street B-IV's, represent the line's fourth generation of cars and were built from 1997 to 1999 by Adtranz. These cars are built to the unusual broad gauge of 5 ft 2 1⁄4 in (1,581 mm), known as "Pennsylvania trolley gauge".

Trolley

The vehicles used on SEPTA's Subway-Surface trolleys were built by Kawasaki in 1981. Known as "K-cars", they use the Pennsylvania trolley gauge of 5 ft 2 1⁄4 in (1,581 mm).

Uniquely, the Girard Street Line uses "PCC II" trolleys, originally built in 1947 by the St. Louis Car Company, which were rebuilt for the line's reopening in 2003 to include air conditioning. The line, like the Subway-Surface lines, is Pennsylvania trolley gauge.

The suburban trolley lines use Kawasaki-built vehicles similar to, but larger than, the Subway-Surface trolleys. They use a slightly wider Pennsylvania trolley gauge, 5' 2-1/2". Notably, they are double ended, unlike the Subway-Surface trolleys, as the suburban lines lack any loops to turn the vehicles on their suburban-bound termini.

Interurban

The Norristown High Speed Line uses a class of cars known as N-5s. They were delivered in 1993 by ABB after significant production delays. These cars are unique in that they are powered by a third rail and are standard gauge.

Regional Rail

SEPTA uses a mixed fleet of General Electric and Hyundai Rotem "Silverliner" electric multiple unit self-operated cars. SEPTA also uses push-pull equipment consisting of coaches built by Bombardier and hauled by AEM-7 or ALP-44 electric locomotives, identical to those used by Amtrak and NJT on its electrified rail services, for express and rush-hour service.

Maintenance-of-way vehicles

- C-145 snow sweeper (1923)

- Harsco Track Technologies Corporation work car – overhead wire snow and ice removal

- PCC work car 2194 – trolley line

- SEPTA Railroad 615 cab car - former Long Island Rail Road power car built from Great Northern FA1 422A

- SEPTA Railroad 622 cab car - former Long Island Rail Road power car built from B&O F7a 265

- SEPTA Railroad OPS-3161 crane railroad work car

- SEPTA Railroad OPS-6214 Fairmont rail grinder

- RRD 520 MOW Hi-Rail Truck

- R-2 (ex 1922 Brill) Market Street revenue car

- W-56 flat bed and crane work car

- W-61 flat bed work car

- 2 Market–Frankford Line M4 work cars

Maintenance facilities

- Transit Divisions

- 69th Street Yard (City Transit Division / Market–Frankford Line, facility is actually located in Delaware County)

- Allegheny Depot (City Transit Division / articulated and standard size buses; formerly housed Nearside, double-ended, and PCC streetcars)

- Berridge Shops (formerly Wyoming Shops, bus maintenance and overhauls)

- Bridge Street Yard (City Transit Division / Market–Frankford Line)

- Callowhill Depot (City Transit Division / bus and streetcar; formerly housed Nearside, Peter Witt, double-ended, and PCC streetcars)

- Comly Depot (City Transit Division / articulated and standard size buses)

- Elmwood Depot (City Transit Division / streetcar, also used as a station. Replaced former Woodland Depot)

- Fern Rock Yard (City Transit Division / Broad Street Line)

- Frankford Depot (City Transit Division / bus and trackless trolley; formerly housed Nearside, double-ended, and PCC streetcars)

- Frontier Depot (Suburban Transit Division / bus)

- Germantown Brakes Maintenance Facility (Germantown Depot, City Transit Division / bus maintenance)

- Midvale Depot (City Transit Division / articulated, standard size, and formerly housed 30-foot (9.1 m) buses. Replaced former Luzerne Depot)

- Southern Depot (City Transit Division / buses only: SEPTA board voted to not have trackless trolleys return to South Philly; formerly housed Nearside, double-ended and Peter Witt streetcars)

- Victory Depot (69th Street, Suburban Transit Division / bus and light rail)[33]

- Woodland Maintenance Facility (streetcar overhaul and repairs. Site of former Woodland Depot, whiche formerly housed Nearside, double-ended, and PCC streetcars)

- Regional Rail

Connecting transit agencies in the Philadelphia region

Local services

The PATCO Speedline is a rapid transit line that runs from Center City Philadelphia to Camden, New Jersey and terminates in Lindenwold, New Jersey. At the 8th Street station, one can transfer to the Market–Frankford Line and Broad–Ridge Spur with an additional transfer fare. Paid transfers are also available at PATCO's 12th–13th Street station and 15th–16th Street station with SEPTA's Broad Street Line Walnut–Locust station. The PATCO Speedline crosses over the Delaware River via the Ben Franklin Bridge. It is owned by the Delaware River Port Authority.

In the western Philadelphia suburbs, Krapf's Transit runs regularly scheduled buses between Coatesville, Downingtown, Exton and West Chester. SEPTA Routes 92 and 104 connect with this service in West Chester, and route 92 also connects with this service at the Exton Square Mall. Krapf's also provide contract services to SEPTA on two routes (204 and 205). They also operate a free express shuttle bus from Center City to the Navy Yard in South Philadelphia as well as a free shuttle bus loop within the Navy Yard itself.

In King of Prussia, the Greater Valley Forge Transportation Management Association runs a community shuttle, the Rambler, which connects with SEPTA at the King of Prussia Mall Transportation Center.

In the northwestern Philadelphia suburbs, Pottstown Area Rapid Transit (PART, formerly known as Pottstown Urban Transit) operates six daytime bus routes and three nighttime bus routes within Pottstown Borough and the neighboring townships of Limerick, Lower Pottsgrove, Upper Pottsgrove, and West Pottsgrove in Montgomery County and North Coventry Township in Chester County. PART and SEPTA have an agreement allowing transfers between PART service and SEPTA Route 93 buses in Pottstown.

Regional services

NJ Transit runs buses from Philadelphia to New Jersey points. Many NJT buses stop at the Philadelphia Greyhound Terminal, which is immediately north of Jefferson Station or at other locations in Center City Philadelphia. NJT also operates the River Line light rail line between Camden and Trenton, the Northeast Corridor Line between Trenton and New York, and the Atlantic City Line between 30th Street Station and Atlantic City. Both the Northeast Corridor Line and River Line connect with SEPTA's Regional Rail Trenton Line at the Trenton train station. Additionally, SEPTA Route 127 connects with NJT bus and rail services at the Trenton Transit Center.

DART First State provides bus service in Delaware. This service connects with SEPTA's Wilmington/Newark Line Regional Rail service in Wilmington and Newark. In 2007, SEPTA bus Route 306 began service, connecting the Great Valley Corporate Center and West Chester with the Brandywine Town Center; service between West Chester and Brandywine Town Center was discontinued in 2010 due to low ridership. In February 2009, SEPTA bus Route 113 commenced connecting bus service with DART at the Tri-State Mall, allowing service between Delaware County and the State of Delaware, and connecting with DART First State's #1 and #61 bus at the Tri-State Mall.

National and international services

Amtrak provides rail service between Philadelphia (at 30th Street Station) and points beyond SEPTA's range, including Lancaster, Harrisburg, Pittsburgh, and Chicago to the west, Baltimore and Washington, D.C. to the southwest, and New York, Boston, and Montreal to the northeast. Amtrak's service overlaps to some degree with the Wilmington/Newark Line, Paoli/Thorndale Line and Trenton Line. In addition to 30th Street Station, shared Amtrak/SEPTA Regional Rail stations include Wilmington and Newark on the Wilmington/Newark Line, Ardmore, Paoli, Exton, and Downingtown on the Paoli/Thorndale Line, and North Philadelphia, Cornwells Heights, and Trenton on the Trenton Line. Amtrak is faster than SEPTA, but significantly more expensive, particularly for services along the Northeast Corridor.

Greyhound and a variety of interregional bus operators, most of which are part of the Trailways system, stop at the Philadelphia Greyhound Terminal. In addition to being adjacent to Jefferson Station, the terminal is one block from the Market–Frankford Line 11th Street station and various SEPTA bus routes. Major destinations served with one seat rides to/from the terminal include Allentown, Atlantic City, Baltimore, Harrisburg, Newark (New Jersey), New York, Pittsburgh, Reading, Scranton, Washington and Wilmington. In addition, six NJT bus routes (313, 315, 316, 317, 318 and 551) originate and terminate from this terminal.

Philadelphia International Airport is served by many airlines with flights to various national and international points. SEPTA serves the airport with local bus service and with the Airport Line from Center City.

Criticism and recognition

SEPTA's 50-year history has often been a tumultuous one, a direct result of the agency being governed at the local county level rather than the state one.[5] Railpace Newsmagazine contributor Gerry Williams observed that SEPTA regularly staggers from crisis to crisis, with little support or oversight originating at the state level in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.[5] Never progressive in management decisions, notoriously apathetic, and quick to suspend rail-based services indefinitely, SEPTA has historically been at odds with the riding public and both local county and state officials.[5] SEPTA has suffered more labor strikes than any other transit agency in the U.S., occurring in 1977, 1981, 1983, 1986, 1995, 1998, 2005, 2009,[34] 2014, [35] and 2016.

Williams commented that there is a notable lack of "any group... influential enough to bring shame on SEPTA,"[5] adding that SEPTA's chronic ills "merely reflect the broader problems of local provincialism and petty political squabbles which are so rampant within the (Delaware Valley) region."[5] The five counties it serves regularly have various hidden agendas working in the background, often at cross purposes with one another than as a unified region, a problem that has resulted in many services being severed mid-route without regard to the affected counties.[5] This factor is regularly influenced by the changing political winds at the state capital in Harrisburg.[5]

SEPTA made strides in the 21st century that helped reverse the downward trend. $191 million of funds made available from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 were utilized to make over 30 major improvements to the system, including renovations of the Spring Garden and Girard Avenue subway stations and built the first Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) station at Fox Chase terminal in 2010. SEPTA also inaugurated a consolidated, multi-modal control center that helps manage all aspects of the system.[36]

SEPTA was voted the best large transit agency in North America by the American Public Transportation Association (APTA) in July 2012. The award was criticized by Next City columnist Diana Lind, stating that despite some outward appearances of improvement, SEPTA still largely operates under a cloud of non-transparency and continues to lack a system-wide expansion program for the future. This is most notable in the regional rail division, which suffered severe cutbacks in the 1980s and whose affected routes have been converted into rail trails, preventing a restoration of those services for the foreseeable future. When asked to produce data pertaining to SEPTA's repeated attempts to consolidate bus stops, Lind observed "the report on the project barely elaborates on the information. SEPTA’s trials deserve public attention and input. The public deserves the data — show us the average times before and after the pilot. Give reader surveys. Tell us why you haven’t tried another pilot on another bus line."[36]

See also

- Doe v. Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority

- List of metro systems

- List of United States rapid transit systems by ridership

- Commuter rail in North America

- List of suburban and commuter rail systems

- List of United States commuter rail systems by ridership

- List of light rail transit systems

- List of United States light rail systems by ridership

- List of United States local bus agencies by ridership

References

- ↑ "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter and End-of-Year 2014" (pdf). American Public Transportation Association (APTA) (via: http://www.apta.com/resources/statistics/Pages/RidershipArchives.aspx ). March 3, 2015. p. 26. Retrieved 2015-04-05. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "The history of trolley cars and routes in Philadelphia". SEPTA. 1974-06-01. p. 2. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

An early city ordinance prescribed that all tracks were to have a gauge of 2' 2 1⁄4"

- ↑ Hilton, George W.; Due, John Fitzgerald (2000-01-01). The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804740142. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

Worst of all, not all city systems were built to the standard American and European gauge of 4'- 8 1⁄2". Pittsburgh and most other Pennsylvania cities used 5'- 2 1⁄2", which became known as the Pennsylvania trolley gauge. Cincinnati used 5'- 2 1⁄2", Philadelphia 5'- 2 1⁄4", Columbus 5'-2", Altoona 5'-3", Louisville and Camden 5'-0", Canton and Pueblo 4'-0", Denver, Tacoma, and Los Angeles 3'-6", Toronto an odd 4'- 10 7⁄8", and Baltimore a vast 5'- 4 1⁄2".

- ↑ "SEPTA Enabling Legislation (74PaCS§1711)". Pennsylvania Legis website.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Williams, Gerry (September 2004). "SEPTA Scene". Railpace Newsmagazine. Piscataway, New Jersey: Railpace Company, Inc. 4 (9): 16–18.

- ↑ "SEPTA Facts". SEPTA Web site.

- ↑ Pawson, John R. (1979). Delaware Valley Rails: The Railroads and Rail Transit Lines of the Philadelphia Area. Willow Grove, Pennsylvania: John R. Pawson. p. 21. ISBN 0-9602080-0-3.

- ↑ Kostelnie, Natalie (9 March 2012). "Dreams of rail service deferred, but not dead". Philadelphia Business Journal. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Kostmayer, Peter. "A Cross-county Metro Would Relieve Traffic". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ pa-tec.org

- ↑ Van Zuylen-Wood, Simon (25 November 2013). "Could the Broad Street Line Expand to the Navy Yard?". Philly Magazine. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "King of Prussia Rail". Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ "Board Members". Philadelphia: SEPTA.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "SEPTA - Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority" (PDF). septa.org.

- ↑ SEPTA (November 2015). "Changes to Route 23 Service - Effective November 29, 2015".

- 1 2 Nussbaum, Paul (May 29, 2009). "SEPTA approves $1.13 billion budget". The Philadelphia Inquirer. section B, p. 03. Archived from the original on 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

SEPTA returned 38 trackless trolleys last year to routes in Northeast Philadelphia, five years after the board voted to suspend all trackless trolley service for one year.

- ↑ "Trolleynews". Trolleybus Magazine. UK: National Trolleybus Association (275): 119. September–October 2007. ISSN 0266-7452.

- 1 2 "Trolleynews". Trolleybus Magazine (280): 95. July–August 2008.

- ↑ Haseldine, Peter, ed. (January–February 2007). "Trolleynews". Trolleybus Magazine. UK. 43 (271): 23. ISSN 0266-7452. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

As a result, the 'indefinite suspension' of trolleybus operation of routes 29 and 79 is now a permanent closure, ...

- ↑ "Philadelphia Transit Vehicles: SEPTA's Commuter Rail Fleet". Philadelphiatransitvehicles.info. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ "Silverliner V Train Makes Debut". SEPTA.org. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ "Silverliner V Service Schedule". SEPTA.org. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ↑ Bohnel, Steve SEPTA urges rail riders to look into work-week alternatives The Philadelphia INQUIRER, July 4, 2016

- ↑ SEPTA Announces Regional Rail Adjustments SEPTA July 3, 2016

- ↑ 2008 SEPTA Railroad Division employee timetable Accessed August 16, 2011

- ↑ SEPTA web site accessed March 2012, http://www.septa.org/police/

- ↑ "Philadelphia Transit Vehicles: History of the Neoplans". Philadelphiatransitvehicles.info. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ "Philadelphia Transit Vehicles: History of the Neoplans". Philadelphiatransitvehicles.info. Part III. Archived from the original on 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ "Philadelphia Transit Vehicles: 1998–2000 Neoplan Order". Philadelphiatransitvehicles.info. Archived from the original on 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ "Trolleynews". Trolleybus Magazine (270): 144. November–December 2006.

- ↑ Cheung, Eric (November 19, 2007). "The Philadelphia Diesel Difference – Working Group Meeting". Clean Air Council. Archived from the original on 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

SEPTA will have the option of ordering an additional 20 hybrid electric buses for each of the four years the 100 contractually obligated buses have been delivered.

- ↑ "An Example of Rear advertising used on SEPTA's DE40LF and D40LF buses". Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ "Philadelphia Transit Vehicles: SEPTA's Bus and Light Rail Assignments by Depot (includes Norristown High Speed Line)". Philadelphiatransitvehicles.info. October 12, 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ Meg Favreau. "SEPTA Strike History and What to Do During a SEPTA Strike". About.com Travel.

- ↑ Mulvihill, Geoff (June 14, 2014). "SEPTA Commuter Rail Union on Strike". WCAU. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: NBC10.com. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- 1 2 Lind, Diana (July 31, 2012). "SEPTA Wins Best Transit Award, Deserves Some Credit (and Criticism)". Next City. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Next City, Inc. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

Further reading

- Cheape, Charles W. (1980). Moving the masses: urban public transit in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, 1880–1912. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-58827-4.

- Pawson, John R. (1979). Delaware Valley Rails: The Railroads and Rail Transit Lines of the Philadelphia Area. John R. Pawson. ISBN 0-9602080-0-3.

- John F. Tucker Transit History Collection (1895-2002) at Hagley Museum and Library.(includes records of the pre-SEPTA Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company and the Philadelphia Transportation Company for the period 1907-1968.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to SEPTA. |

| Wikinews has related news: US commuter rail accident in Pennsylvania injures over 30 |